Key Points

-

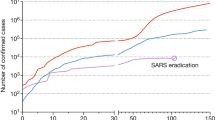

A new infectious disease, called severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), appeared in southern China in 2002. During the period from November 2002 to the summer of 2003, the World Health Organization recorded 8098 probable SARS cases and 774 deaths in 29 countries.

-

A previously unknown coronavirus was isolated from FRhK-4 and Vero E6 cells inoculated with clinical specimens from patients. A virus with close homology to SARS-CoV was isolated from palm civets and racoon dogs, which are used as food in southern China

-

In less than a month from the first indication that a coronavirus might be implicated in the disease, the nucleotide sequence of the virus was available, and diagnostic tests were set up.

-

The phylogenetic analysis of the SARS-CoV genome revealed that the virus is distinct from the three known groups of coronaviruses and represents an early split-off from group 2.

-

The development of antiviral drugs or vaccines is being investigated. Viral enzymes essential for virus replication, such as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), the 3C-like cystein protease (3Clpro) and the helicases are the most attractive targets for antiviral molecules. Of the possible vaccine targets, the spike (S) protein represents the most promising one.

-

So far, β-interferon is the only licensed drug available, which has been reported to interfere with virus replication in vitro. Should SARS return during the next winter, we will still need to rely mostly on quarantine measures to contain it.

Abstract

The 114-day epidemic of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) swept 29 countries, affected a reported 8,098 people, left 774 patients dead and almost paralysed the Asian economy. Aggressive quarantine measures, possibly aided by rising summer temperatures, successfully terminated the first eruption of SARS and provided at least a temporal break, which allows us to consolidate what we have learned so far and plan for the future. Here, we review the genomics of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), its phylogeny, antigenic structure, immune response and potential therapeutic interventions should the SARS epidemic flare up again.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Accession codes

References

Peiris, J. S. M. et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 361, 1319–1325 (2003). This paper reports microbiological findings and clinical presentation of SARS in 50 patients. The authors also define the risk factors and investigate the causal agent by chest radiography and laboratory testing of patients' samples.

Donnelly, C. A. et al. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet 361, 1761–1766 (2003).

Hon, K. L. et al. Clinical presentations and outcome of severe acute respiratory syndrome in children. Lancet 361, 1701–1703 (2003).

Peiris, J. S. M. et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 361, 1767–1772 (2003).

WHO. Acute respiratory syndrome in China. [online], (cited 15 Oct 2003), <http://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_2_20/en/> (2003).

WHO. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. [online], (cited 15 Oct 2003), <http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2003_09_23/en/> (2003).

Drosten, C. et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1967–1976 (2003).

Ksiazek, T. G. et al. A Nnvel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1953–1966 (2003).

Fouchier, R. A. et al. Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature 423, 240 (2003).

Kuiken, T. et al. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 362, 263–270 (2003).

Riley, S. et al. Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science 300, 1961–1966 (2003).

Lipsitch, M. et al. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 300, 1966–1970 (2003).

Guan, Y. et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science 302, 276–278 (2003).

Normile, D. & Enserink, M. SARS in China: tracking the roots of a killer. Science 301, 297–299 (2003).

WHO. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Singapore. [online], (cited 15 Oct 2003), <http://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_09_24/en/> (2003).

Enjuanes, L. et al. in Virus Taxonomy (eds Regenmortel, M. H. V. et al.) 835–849 (Academic Press, New York, 2002).

Marra, M. A. et al. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science 300, 1399–1404 (2003).

Rota, P. A. et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 300, 1394–1399 (2003). References 17 and 18 are the first reports of the complete genome sequences of two SARS-CoV isolates (TOR2 and Urbani strains, respectively). In each case, the authors present the viral genome organization, describe the main features of the predicted ORFs and provide a phylogenetic analysis that places SARS-CoV in a new group.

Zeng, F. Y. et al. The complete genome sequence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus strain HKU-39849 (HK–39). Exp. Biol. Med. 228, 866–873 (2003).

Thiel, V. et al. Mechanisms and enzymes involved in SARS coronavirus genome expression. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 2305–2315 (2003). The complete genome sequence of a SARS-CoV isolate (FRA) and experimental data on its key RNA elements and protein functions are described. The enzymatic activity of the SARS-CoV helicase and two proteinases is shown.

Thiel, V., Herold, J., Schelle, B. & Siddell, S. G. Viral replicase gene products suffice for coronavirus discontinuous transcription. J. Virol. 75, 6676–6681 (2001).

von Grotthuss, M., Wyrwicz, L. S. & Rychlewski, L. mRNA cap-1 methyltransferase in the SARS genome. Cell 113, 701–702 (2003).

Lai, M. M. & Cavanagh, D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 48, 1–100 (1997).

van der Most, R. G. & Spaan, W. J. M. in The Coronaviridae. (ed. Siddell, S. G.) 11–31 (Plenum Press, New York, 1995).

de Haan, C. A. M., Masters, P. S., Shen, X., Weiss, S. & Rottier, P. J. M. The group-specific murine coronavirus genes are not essential, but their deletion, by reverse genetics, is attenuating in the natural host. Virology 296, 177–189 (2002).

Sola, I. et al. Engineering the transmissible gastroenteritis virus genome as an expression vector inducing lactogenic immunity. J. Virol. 77, 4357–4369 (2003).

Sarma, J. D., Scheen, E., Seo, S. H., Koval, M. & Weiss, S. R. Enhanced green fluorescent protein expression may be used to monitor murine coronavirus spread in vitro and in the mouse central nervous system. J. Neurovirol. 8, 381–391 (2002).

Jonassen, C. M., Jonassen, T. O. & Grinde, B. A common RNA motif in the 3′ end of the genomes of astroviruses, avian infectious bronchitis virus and an equine rhinovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 79, 715–718 (1998).

Lai, M. M. & Holmes, K. V. in Fields' Virology. (eds Knipe, M. D. & Howley, M. P) 1163–1185 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2001).

Ruan, Y. J. et al. Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS coronavirus isolates and common mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet 361, 1779–1785 (2003).

Ksiazek, T. G. et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1953–1966 (2003).

Snijder, E. J. et al. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 331, 991–1004 (2003). The authors describe the genome organization and expression strategy of the SARS-CoV. A phylogenetic analysis of the ORF1b indicates that the SARS-CoV represents an early split-off from group 2 coronaviruses.

Anand, K. et al. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra α-helical domain. EMBO J. 21, 3213–3224 (2002).

Anand, K., Ziebuhr, J., Wadhwani, P., Mesters, J. R. & Hilgenfeld, R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science 300, 1763–1767 (2003). In this work, the three-dimensional structures of the uncomplexed proteinase 229E-HCoV 3CL and of TGEV 3CL-pro in complex with an inhibitor have been solved. On the basis of these structures, the authors provide a three-dimensional model of the main proteinase of SARS-CoV, and using molecular modelling, they suggest the construction of possible novel SARS-CoV inhibitors.

Krokhin, O. et al. Mass Spectrometric Characterization of proteins from the SARS virus: a preliminary report. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2, 346–356 (2003).

Cavanagh, D. in The Coronaviridae. (ed. Siddell,S. G.) 73–113 (Plenum Press, New York, 1995).

Kuo, L., Godeke, G. J., Raamsman, M. J. B., Masters, P. S. & Rottier, P. J. M. Retargeting of coronavirus by substitution of the spike glycoprotein ectodomain: crossing the host cell species barrier. J. Virol. 74, 1393–1406 (2000).

Haijema, B. J., Volders, H. & Rottier, P. J. M. Switching species tropism: an effective way to manipulate the feline coronavirus genome. J. Virol. 77, 4528–4538 (2003).

Yu, X. J. et al. Putative hAPN receptor binding sites in SARS-CoV spike protein. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 24, 481–488 (2003).

Tresnan, D. B. & Holmes, K. V. Feline aminopeptidase N is a receptor for all group I coronaviruses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 440, 69–75 (1998).

Holmes, K. V., Zelus, B. D., Schickli, J. H. & Weiss, S. R. Receptor specificity and receptor-induced conformational changes in mouse hepatitis virus spike glycoprotein. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 494, 173–181 (2001).

Bosch, B. J., van der Zee, R., de Haan, C. A. M. & Rottier, P. J. M. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 77, 8801–8811 (2003). The authors describe the structure of two heptad repeat regions (HR1, HR2) in the S2 domain of murine hepatitis virus. A peptide, corresponding to HR2, had a concentration-dependent inhibitory effect on virus entry into the cells, as well as cell–cell fusion.

Bos, E. C., Luytjes, W. & Spaan, W. J. The function of the spike protein of mouse hepatitis virus strain A59 can be studied on virus-like particles: cleavage is not required for infectivity. J. Virol. 71, 9427–9433 (1997).

Gombold, J. L., Hingley, S. T. & Weiss, S. R. Fusion-defective mutants of mouse hepatitis virus A59 contain a mutation in the spike protein cleavage signal. J. Virol. 67, 4504–4512 (1993).

Taguchi, F. Fusion formation by the uncleaved spike protein of murine coronavirus JHMV variant cl-2. J. Virol. 67, 1195–1202 (1993).

Hingley, S. T., Leparc-Goffart, I., Seo, S. H., Tsai, J. C. & Weiss, S. R. The virulence of mouse hepatitis virus strain A59 is not dependent on efficient spike protein cleavage and cell-to-cell fusion. J. Neurovirol. 8, 400–410 (2002).

Stauber, R., Pfleiderera, M. & Siddell, S. Proteolytic cleavage of the murine coronavirus surface glycoprotein is not required for fusion activity. J. Gen. Virol. 74, 183–191 (1993).

Cinatl, J. et al. Treatment of SARS with human interferons. Lancet 362, 293–294 (2003).

Cinatl, J. et al. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet 361, 2045–2046 (2003). This paper reports the first results obtained for the search of possible SARS inhibitors. The authors show that, among other compounds tested, glycyrrhizin is the most active in inhibiting replication of the virus.

Olsen, C. W. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus: molecular biology, immunopathogenesis, clinical aspects, and vaccination. Vet. Microbiol. 36, 1–37 (1993).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie and the Chiron Vaccines Cellular Microbiology and Bioinformatics Unit for their continuous support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Abrignani, R. Rappuoli, K. Stadler and V. Masignani are employed by Chiron Corporation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stadler, K., Masignani, V., Eickmann, M. et al. SARS — beginning to understand a new virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 1, 209–218 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro775

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro775

This article is cited by

-

Molecular docking unveils the potential of andrographolide derivatives against COVID-19: an in silico approach

Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (2022)

-

An extended motif in the SARS-CoV-2 spike modulates binding and release of host coatomer in retrograde trafficking

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Differing coronavirus genres alter shared host signaling pathways upon viral infection

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Ionic contrast across a lipid membrane for Debye length extension: towards an ultimate bioelectronic transducer

Nature Communications (2021)

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: The prediction of the lifetime of the new coronavirus in the USA using mathematical models

Soft Computing (2021)