Abstract

The presence of salts and related salt-induced damage represent one of the major threats to the preservation of our built heritage. Identifying critical relative humidity values that facilitate crystallization cycles is essential for understanding damage risks and extents. This knowledge helps in developing recommendations for favorable, damage-avoiding climates, particularly in controllable indoor environments. While for single salts their deliquescence humidity is known, for multi-ion mixtures relevant for the built heritage multiple transitions happen over a range of relative humidity. Modeling of equilibrium crystallization pathways is possible, e.g. using the Pitzer formalism. However, for complex mixtures, only predictions can be given, which need to be validated through experimental results. This work focuses on the use of dynamic water vapor sorption measurements to investigate phase transitions in salt mixtures, demonstrating its applicability, scrutinizing different influencing factors and an appropriate interpretation of results. Additionally, presenting an experimental design that delivers reliable results for the conservation of cultural heritage is crucial. In addition to single salts, mixtures from the common hygroscopic system Na+–K+–Mg2+–Ca2+–Cl––NO3––H2O are investigated, including their behavior in a stone material. The identified transitions are compared to the calculated behavior using the ECOS–Runsalt model. The presented results are accurate and reproducible. They show the ability to determine the critical relative humidity ranges (in bulk and in porous materials) and validate thermodynamic models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Damage to porous building materials as a result of salt crystallization from a supersaturated pore solution1 is one of the major threats to cultural heritage. Seven ions, Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl–, NO3– and SO42–, are the most abundant and should always be considered in salt formation in heritage buildings2. Salt crystallization occurs only under specific climatic conditions. In this sense, each salt has a specific temperature dependent relative humidity (RH) value \(\varphi\) = p/p0 with p the vapor pressure and p0 the saturation vapor pressure of water at which the salt begins to absorb water vapor from the surrounding air to form a saturated solution. At this relative humidity water vapor, salt solution and crystalline salt are in equilibrium3. This value is called the deliquescence humidity (DRH) and a wide range of values is covered by the different salts relevant to cultural heritage. Considering the seven ions mentioned above, the single salt with the lowest DRH is CaCl2 ∙ 6H2O (29%)4, while CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O has an extremely high DRH of more than 99.99%5. If the relative humidity is lower than the water activity of the saturated salt solution, only crystalline salt is present. If it is higher, the salt dissolves completely and the solution dilutes by absorbing water vapor from the surrounding.

For heritage buildings, the presence of one specific salt or its corresponding ions is unlikely. Instead, more or less complex ion mixtures accumulate in the porous host that arise from different sources depending on location, use and conservation history of the object6,7. In case of mixtures, there is no longer one specific value of DRH since the ions influence each other. The precipitation of salts during drying of a mixed solution (or the dissolution of a solid mixture under conditions of humidification) occurs over a range of relative humidity. Going from high to low humidity, the first phase precipitates at the so-called critical (mutual)8 crystallization humidity \(\varphi\)m,cry and the relative humidity below which all phases are crystalline is called the mutual deliquescence humidity \(\varphi\)m,del7,9. Consequently, between \(\varphi\)m,cry and \(\varphi\)m,del salt solution and crystalline salts coexist. All other onset points for crystallization of additional phases between these two values are mutual crystallization humidities. It should be noted that \(\varphi\)m,del is the same for mixture compositions for a given combination of ions, while the critical crystallization humidity of the first precipitating phase and the mutual crystallization humidities depend on the mixing ratio. Recently, the relevant processes for crystallization and dissolution of mixed electrolytes have been summarized by Godts et al. 8. It is worth noting that the crystallization of the first precipitating phase always starts at a lower humidity than the deliquescence humidity of the respective pure salt and, like the DRH of single salts, the values relevant for mixtures are also temperature dependent8.

To illustrate the processes described, Fig. 1 shows the saturation humidity as a function of the mole fraction x of NaCl in a mixture with KCl at 25 °C and considering that equilibrium conditions are met at each relative humidity. For a crystalline salt mixture of any composition, the dissolution starts at the mutual deliquescence humidity of 72.1% and the crystalline mixture starts to pick up water. At compositions x(NaCl) < 0.705 (corresponding to point \(\varphi\)m,del), this leads to complete dissolution of NaCl and partial dissolution of KCl. Upon further increase of \(\varphi\), the dissolution of KCl continues and the solution becomes more dilute, following the arrows from \(\varphi\)m,del to point A, the latter being the critical crystallization humidity of that mixture (82.6%). Between \(\varphi\)m,del and \(\varphi\)m,cry salt solution and crystalline KCl coexist. Further increase of the relative humidity above\(\,\varphi\)m,cry leads to dilution of the solution. It has to be noted that for solution compositions of x(NaCl) > 0.705 the process starts with the complete dissolution of KCl and partial dissolution of NaCl.

DRH of the single salts and \(\varphi\)m,del of the system are shown as green, blue and red dots, respectively. Point A depicts \(\varphi\)m,cry of a salt mixture with x(NaCl) = 0.2, A’ the equilibrium humidity of a more dilute solution of the same composition and point B an exemplary crystallization humidity considering supersaturation upon evaporation from a solution starting at A’. Blue arrows indicate the pathway upon water uptake, red arrows and lines represent processes upon evaporation with some degree of supersaturation.

Now considering the evaporation of a salt solution of the same composition x(NaCl) = 0.2 but at higher relative humidity of 87.5% corresponding to A’ instead, a decrease of \(\varphi\) leads to evaporation and an increase of the solution concentration. However, depending on the rate of the relative humidity change due to supersaturation, KCl will not start to precipitate at point A, but at a lower relative humidity, in Fig. 1 exemplarily given as point B. When crystallization sets in, the saturation concentration corresponding to this lower relative humidity is achieved and from then on, the solution composition moves along the equilibrium curve (following the red lines and arrows in Fig. 1).

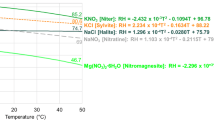

The calculation of crystallization and dissolution equilibria requires the determination of concentration and temperature dependent activity and osmotic coefficients describing the highly non-ideal behavior of salt solutions. Appropriate thermodynamic models allow the calculation of this information for solutions of one or more solutes. One such model is the ion interaction model of Pitzer10. For example, the model used to calculate the saturation humidity shown in Fig. 1 is a molality based Pitzer model11. The free software ECOS–Runsalt2,12 is based on the mole fraction Pitzer approach to calculate phase transitions in the multicomponent system Na+–K+–Mg2+–Ca2+–Cl––NO3––SO42––H2O at variable climatic conditions10. It should be noted, that such thermodynamic models always consider equilibrium conditions and neglect kinetic influences (such as supersaturation or metastable crystallization pathways)8.

Since the calculations are predictions for mixtures containing more than three ions it is appropriate to validate such models by investigating the behavior of salt mixtures under different ambient moisture conditions. The results might also contribute to the further improvement of such models. In terms of prediction of salt damage to masonry, an accurate knowledge of the phase transition processes and the behavior of salt mixtures under different ambient moisture conditions is fundamental. Defining the relevant climatic conditions for crystallization, dissolution and hydration, is vital to understand the damage phenomena and to develop appropriate conservation measures to slow down further decay.

A particularly useful method to investigate the hygroscopic behavior of a salt (mixture) experimentally is dynamic water vapor sorption (DVS), where a sample is accurately weighed in a climatic chamber at known temperature and relative humidity13,14,15. The gravimetric measurement at a given \(\varphi\) is continued until the sample weight is constant before the next relative humidity is set and the measurement cycle is repeated. This technique has already been successfully used to measure the water sorption behavior of different stone materials and sandstones impregnated with a salt mixture containing Na+, Mg2+, NO3– and SO42–16,17. In addition, DVS was used to determine \(\varphi\)m,del and \(\varphi\)m,cry (also to evaluate existing models) with lab-prepared salt mixtures (four ternary and one quaternary mixture) and to investigate critical humidity ranges for real objects with micro samples to minimize the required sample mass. The results obtained from this method can also guide conservation efforts to prevent deterioration under specific climatic conditions13,14,15. These investigations revealed that a sample mass of 5 mg is sufficient to obtain reliable results if a precision balance is used.

In the present work, DVS is used to investigate different single salts and salt mixtures with relevance to salt contaminated cultural heritage. In this study, the automated moisture sorption analyzers SPSx-1 µ Advanced and SPSx-1 μ High Load (proUmid GmbH) were used, equipped with a micro-balance and sample holders that allow the investigation of 23 samples in a single run. Considering the interest in direct measurements of the sorption behavior of real building material samples contaminated with salt, the investigations also include sandstone specimens impregnated with mixed electrolytes. The study focuses on pure sodium chloride and several more hygroscopic mixtures containing Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl– and NO3–. Following the classification of Godts et al. 18 these are calcium-rich mixtures. This classification is related to the most relevant ions (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl–, NO3– and SO42–) for salt contaminated built heritage. Gypsum is the least soluble salt precipitating from that system and it does not influence the properties of the other salts. When gypsum is removed from the solution, the system will contain either sulfate or calcium ions, and the two subsystems Na+–K+–Mg2+–Cl––NO3––SO42––H2O and Na+–K+–Mg2+–Ca2+–Cl––NO3––H2O remain, the latter being more hygroscopic. Salination with ions of this calcium-rich system is widespread19,20,21, and as recently shown22 such hygroscopic mixtures are almost as common as sulfate-rich (less hygroscopic) type 1 mixtures. However, they have received less attention in salt research in the past. The main research objective of the present work was to investigate the main factors influencing the practical use of the method, as well as the evaluation of the level of accuracy required in practical applications in heritage conservation. Further attention is given to the interpretation of the measurements and how to extract a maximum of information from the measured curves. In addition, model calculations performed with ECOS–Runsalt were used to assign the observed phase transitions to individual salts of the mixtures but also to validate the model calculations for complex mixtures.

Dynamic water vapor sorption

Commonly, a dynamic water vapor sorption measurement starts with a dry sample which is equilibrated at 0% RH and constant temperature, e.g. 25 °C. The relative humidity is then increased in steps, the size of which can be varied to suit the measurement requirements. The gravimetric measurement at a given RH is continued until the sample mass is constant, thus, equilibrium is established. However, equilibration times required to reach full equilibrium may be very long (even weeks) depending on the properties and size of the sample under investigation. Alternatively, RH can also be changed after a defined amount of time (the hold time th) making the measurement faster and accepting that full equilibrium is not achieved. By increasing the relative humidity, the sample picks up water, initially only small amounts by adsorption. A sudden increase in the water uptake is an indication of a phase transition, e.g. at the deliquescence humidity of a single salt or a salt mixture, or at the hydration humidity of a salt with several hydrated phases. In the case of single salts, further absorption of water vapor leads to the continuous dilution of the salt solution. Equilibrium is now established if the relative humidity equals the water activity aw of the solution (φ = aw). Due to their non-ideal behavior, there is no simple relation between water activity and the concentration of salt solutions and thermodynamic models such as those mentioned before are used to calculate aw. Thus, if carried out under equilibrium conditions, DVS measurements allow for an accurate determination of the equilibrium relative humidity (or water activity) of salt solutions, or, they can be used for model validation.

An exemplary sorption isotherm for sodium chloride is depicted in Fig. 2. It includes the weight of absorbed water at the distinct relative humidities showing an obvious mass increase due to deliquescence and a continuous mass increase after deliquescence.

Measured at 25 °C with RH steps of 2% and a hold timeof 8 h per step (during the measurement equilibrium conditions were accepted when the weight change was less than 0.01% over 40 min; if equilibrium was achieved in less than 8 h, the relative humidity was increased already before the maximum hold time). Dashed line: DRH of NaCl (75.3% at 25 °C 11).

During the subsequent desorption, the sample loses water continuously by evaporation with decreasing relative humidity. Thus, if a dilute solution is initially present, it will become more concentrated. Above the deliquescence or critical crystallization humidity, the absorption and desorption branches are congruent because solutions with the same concentration (water content) have the same water activity. When the DRH (for single salts) or \(\varphi\)m,cry (for a salt mixture) is reached, a hysteresis is usually observed between the two branches, as the solution supersaturates prior to crystallization. Therefore, the crystallization step occurs at a lower relative humidity than the deliquescence step upon sorption as can be seen in Fig. 2 for NaCl. After crystallization from the supersaturated solution, the equilibrium relative humidity is achieved again leading to congruent absorption and desorption branches. With the possibility of detecting the crystallization humidity upon desorption, the technique also allows the investigation of the supersaturation achievable under the measurement conditions. In addition, the time elapsing to reach constant weight can provide information on the kinetics of the water uptake and release.

A common method in the field of conservation is the determination of the hygroscopic moisture content (HMC)23,24,25, where the mass gain of a sample (e.g. drilling powder of a real object) stored at a relative humidity of usually about 95% RH (using desiccators and saturated salt solutions or climate chambers) is determined to investigate whether humidity can be assigned to hygroscopic salts or to the presence of other active moisture sources like rising damp. In other applications, the authors attempted to use HMC as an analytical tool to quantify the salt content of material samples23,26,27. Indeed, HMC and DVS are equivalent methods (from both a sorption isotherm is obtained), but with a different setup, the DVS investigating several relative humidities automatically and the HMC being much more time consuming and, therefore, covering less relative humidity steps. Consequently, data obtained from HMC experiments can also be determined with DVS (equilibrium) measurements, which offer additional information, relevant for conservation.

Materials and methods

The salts KNO3, NaNO3, Ca(NO3)2 ∙ 4H2O, Mg(NO3)2 ∙ 6H2O, MgCl2 ∙ 6H2O, NaCl (Carl Roth), KCl and CaCl2 ∙ 2H2O (Merck) were used in analytical grade quality (p.a.) without further purification. They were used as crystalline salts or in solution, the latter being prepared with doubly distilled water. Physical mixtures of crystalline salts were prepared by grinding weighed quantities of the salts using mortar and pestle. Next to bulk solutions and physical mixtures of crystalline salts, cubic specimens (maximum edge length of 4 mm) of Sand sandstone impregnated with mixed solutions were investigated. A MICROMOT drill IBS/E, (PROXXON, Luxemburg) with a diamond coated disk was used to cut the test specimens from larger stone blocks. Prior to impregnation, the stone specimens were washed with doubly distilled water and dried at 130 °C. Sand sandstone mainly consists of quartz, rock fragments and alkali feldspar; clay minerals are present as cementing material. The stone has a bimodal pore size distribution with main pore sizes between 6 and 11 µm and a small fraction of pores <0.1 µm (investigated with mercury intrusion porosimetry as described in28). The sandstone has a cation exchange capacity of 53.8 meq∙kg–1 (mainly Mg2+ and Ca2+)29, which can lead to mixed pore solutions as these ions are partly replaced by ions of the impregnating solution and change the composition of the latter. For Na+ and K+ the maximum removal from an impregnating solution equals 0.124 w.% and 0.210 w.%, respectively, replaced by Mg2+ and Ca2+. As the impregnation solutions in the present experiments had concentrations of at least 2 mol∙kg–1 only a negligible effect on the composition of the pore solutions is expected and there was no need for an ion exchange pretreatment with the same relative composition as the impregnating solutions.

For the DVS experiments with single salts, salt mixtures, impregnated and untreated reference sandstone samples, automated moisture sorption analyzers SPSx-1 µ Advanced and SPSx-1 μ High Load (proUmid GmbH, Germany) were used, allowing the simultaneous investigation of 23 samples in the temperature and relative humidity controlled chambers of the instruments. During the measurements the sample dishes are automatically positioned on a micro-balance to weigh the sample mass at predefined time intervals (in this study 15 or 30 min). All isotherms were recorded at 25 °C, the range of relative humidities starting at 0 or 15% and the upper limit varying between 80 and 95%. To investigate the influence on the detectability and accuracy of phase transitions in the isotherms, different hold times were used. First, near equilibrium runs with 1% RH steps after equilibration of all 23 samples (weight change of less than 0.05% during a period of 3 h) hereafter referred to as method A, were carried out. Such measurements typically resulted in a total duration of the measurement of 128 days. Second, faster non-equilibrium runs (method B) with RH steps of 2% every five, six or ten hours were conducted (maximum duration of the measurements: 20, 24 and 40 days, respectively). In the chamber, T and RH are monitored continuously, the sensors having an uncertainty of ± 0.1 °C and ± 0.5% RH, respectively.

Prior to the sorption measurement, crystalline salts or salt solutions were placed on weighed aluminum dishes suitable for the DVS device and dried at 60 °C for at least 48 h. Sample masses varied between 4.3 and 12 mg for crystalline salts, 6.1 and 13 mg for salt solutions (weight before drying at 60 °C) and 95.8 and 250 mg for sandstones (weight before impregnation). Such small sample weights were used to accelerate equilibration in the instrument. Sample compositions are summarized in Table 1. To investigate more closely the influence of the sample weight, additional sorption isotherms were recorded for different masses of NaCl (ranging from 5.59 to 206 mg). For these measurements the relative humidity range was narrower (60–84%) and the humidity was increased in 2% steps every six hours.

In addition to the evaluation of the sorption isotherms, the first derivative (Δw ∙ Δ\(\varphi\)–1) of the curves was used to allow a better detection of phase transitions. The course of the first derivative was then compared with results from ECOS–Runsalt calculations2,12 for exactly the same conditions and sample compositions to assign the detected phase transitions and to evaluate the model predictions. The ECOS–Runsalt software allows the calculation of crystallization pathways for different climatic conditions for mixture composition from the multi-ion system Na+–K+–Mg2+–Ca2+–Cl––NO3––SO42—H2O considering equilibrium conditions. The results give information of the crystallizing phases, corresponding crystallization humidities and the amount of crystallizing salt in dependence of the relative humidity. The resolution of ECOS calculations was between 0.16% RH and 1.4% RH depending on the range chosen for the calculations. Further details on the method have been discussed recently by Godts et al.8,18.

Results and discussion

Single salts

First, experiments with the single salts NaCl (see Fig. 2), NaNO3 and KCl were performed to determine the accuracy of the detected deliquescence humidity under non-equilibrium conditions (method B) with RH steps of 2% and hold times of 8 h. Upon water uptake for all three salts investigated, distinct steps in the sorption isotherms were detected (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). It can be noted that the step in the sorption curve is not sharp, but includes two data points for KCl and one for NaCl and NaNO3, leading to deliquescence humidities in the range of 85 ± 3%, 76 ± 2% and 74 ± 2%, respectively, giving a sufficient accuracy for practical consideration in the field of salt contaminated built heritage. For NaNO3 an increased mass can already be observed at 74% which means that water sorption already started between 72 and 74% (between the last data point before the step and the first within the step). For KCl the water uptake commences between 82 and 84%. In the literature DRH values of 75.3, 74.0 and 84.3%, respectively, can be found11. Hence, there is some water uptake detected slightly below the DRH. Considering the relative humidity corresponding to the highest mass increase in the step of the sorption curve and the uncertainty of the measurement (given a step size of 2% the determined DRH also have an uncertainty of at least ±2%), literature values can be reproduced for the three salts also at hold times far shorter than required to reach equilibrium.

At this point, it should be emphasized that the accuracy of the determined DRH essentially depends on the measurement conditions (step size, hold-time and sample mass). Using very small step sizes and very long hold-times (like in a measurement under near equilibrium conditions), very accurate values can be obtained. The accuracy is then limited by the accuracy of the RH sensor, which is the lowest reasonable step size. When the step size exceeds the accuracy of the sensor, the error is at least as large as the RH interval. Too short hold times lead to systematic deviations with too high values and less sharp steps in a scan with increasing RH if the dissolution process requires more time.

An increasing sample mass also increases the time required to reach equilibrium and, thus, leads to less sharp steps in the isotherms. To investigate this effect more systematically, sorption isotherms with different amounts of NaCl were performed (method B, RH step size: 2%, hold time: 6 h). Figure 3 depicts the isotherms in terms of the mass of water per milligram of salt detected for five different sample masses between 12.6 and 206 mg and for the sample already shown in Fig. 2 (2.85 mg) which was investigated with a hold time of 8 instead of 6 h. Figure 3 also includes the calculated equilibrium water uptake of NaCl11. It is obvious that the sample mass has a huge impact on the results of sorption measurements. Comparing measured and calculated courses, reveals that with increasing mass the deliquescence step becomes less sharp and the measured curves deviate more and more from the calculated one. Figure 4 depicts the mass vs. time curves for the six samples in the humidity range 74–84% during sorption. It is obvious that only the water uptake of the sample with the smallest initial mass reaches a plateau, thus, full equilibrium within the available time. With increasing sample mass, the equilibration time is too short to reach a state of equilibrium. Consequently, the DRH cannot be determined accurately and the samples even continue to absorb water vapor from the environment when the humidity already decreases again (from 84% during desorption, see Fig. 3). Micrographs of some samples at \(\varphi\)>DRH in Fig. S2 in the supplementary material show the incomplete dissolution of larger samples and the ongoing dissolution during desorption. This kinetic influence results in atypical curves for sample masses above 12.6 mg, in which no congruent curves for sorption and desorption are obtained above the deliquescence humidity (Fig. 3).

Measured with method B (step size of 2% and a hold time of 6 h; except the 2.85 mg sample, which was measured with a hold time of 8 h) and a calculated equilibrium course11.

However, it should be noted that even for large amounts of salt accurate sorption curves that reproduce the DRH can be achieved if the hold time is increased. The result demonstrates the need for small sample amounts in order to accelerate equilibration and, thus, to allow for shorter hold times. Apart from faster equilibration, small sample masses are also important to avoid the risk of large solution volumes exceeding the dish capacity during sorption resulting in overflow and contamination of the device.

Investigation of quaternary salt mixtures

Mixtures of the quaternary system Na+–K+–Cl––NO3––H2O (mixture 1) were chosen as this is an extensively studied system that allows a reliable prediction of phase transitions with ECOS–Runsalt for comparison. First, a sample prepared by mixing crystalline NaCl and KNO3 (sample cr, molar ratio 1:1.3) is discussed, which was investigated with method B (2% change of RH every 5 h). Only one explicit step is visible in both the sorption and the desorption curves (black and gray dots in Fig. 5a), with the desorption step occurring at slightly lower relative humidity than the sorption step. This hysteresis is the result of supersaturation prior to crystallization during drying. A useful way of examining the curves more closely with regard to phase transitions and to detect transitions that only provoke small steps or otherwise might be hidden, is to look at the first derivative Δw ∙ Δ\(\varphi\)–1, shown in Fig. 5b for the sorption curve. A maximum in the first derivative reflects a point with a large slope corresponding to a maximum water uptake as a result of a phase transition in the sorption experiment. The first derivative has two maxima, a pronounced one at 68–70% and a much weaker one around 76%. It has to be noted that even though the water uptake of the corresponding phase transition is the highest at the maximum, the deliquescence or transition already starts earlier, in this case between 66–68% and 74–76%, respectively. Hence, maxima in the first derivative do not exactly match the transition humidities. For distinct maxima like the one shown in Fig. 5b, it is possible to determine the relative humidity range in which the transition occurs. Consequently, apart from the step visible in Fig. 5a at 66–68% (corresponding to the distinct maximum in Fig. 5b), the first derivative reveals another phase transition. The corresponding discontinuity in the sorption curve cannot be easily detected from the original water uptake curve.

a Sorption and desorption curve of an initially crystalline mixture of KNO3 and NaCl (sample cr) investigated with method B (2% change of \(\varphi\) every 5 h) with the corresponding first derivative of the sorption curve and ECOS calculations in (b); c sorption curves of the samples 1 (black dots; 2% change of \(\varphi\) every 10 h), SAN-1 (red diamonds, salt content 1.5 w.%, method A) and reference SAN-0 (green diamonds; method B with 2% change of \(\varphi\) every 5 h); d corresponding first derivative curves and ECOS calculations.

The weaker maximum in Fig. 5b can be attributed to the critical crystallization humidity, i.e. the last phase transition during water uptake. Figure 5b also includes the result of the ECOS–Runsalt calculation for the same mixture composition allowing a direct comparison of detected and calculated phase transitions. As the relative humidity increases, the model predicts the complete dissolution of NaCl, the partial dissolution of KNO3 and the crystallization of a very small amount of KCl at 66.6% (the mutual deliquescence humidity). A large amount of salt is dissolved at this point resulting in a significant increase in absorbed water, which can be derived from the sorption curve.

With increasing relative humidity both KNO3 and KCl dissolve continuously. As the amount of KCl is small however, its crystallization and subsequent dissolution fall into the same RH interval and are not visible in the DVS curve nor in the first derivative. The predicted critical crystallization humidity is 80%. At this RH, the gradual dissolution of KNO3 is complete. Due to the continuous water uptake and the small amount of salt that dissolves gradually the final step of complete dissolution is not visible in the sorption curve but can be detected in the first derivative. The detected value for \(\varphi\)m,cry occurs at lower values than calculated. The reason for the deviation between detected and calculated values of this well-investigated and parameterized system could be due to both measurement and calculation errors. At non-equilibrium measurement conditions, the detected values should always be slightly higher than the thermodynamically calculated values as a result of the kinetic influence, as the hold time at each relative humidity step might be shorter than the time required by the system to achieve equilibrium with the respective humidity. In fact, Fig. S3 in the supplementary material shows that the measurement conditions (sample mass and hold time) did not allow full equilibration such that kinetics lead to a shift of signals to higher values. As the sample was prepared just by grinding the two crystalline salts, it is possible that the phases were not perfectly mixed. Partial unmixing could also occur due to the movement of the sample dish in the instrument. The dishes are mounted on a carrousel so particles in powdered samples may have moved to the outer edge of the dish over time leading to fractionation. More precisely, an effect on the measured deliquescence humidities is possible if some NaCl and KNO3 crystals are isolated, so that they are not influenced by the presence of the other crystal. These crystals would not dissolve at the lower transition humidity and the composition of the mixture of salts actually in contact could differ from that originally intended. Consequently, such imperfect mixing might explain the observed deviations from the model predictions, even though the extent of unmixing is expected to be small. This discussion highlights the importance of the sample preparation in terms of homogeneity. Even though fractionation may also affect homogeneity after crystallization from a droplet, a more homogeneous distribution is obtained when starting with solution droplets that are dried prior to the measurement. Thus, the samples presented below were prepared in this way.

Figure 5c shows the result of a measurement of a dried droplet of a solution containing equimolar amounts of NaCl and KNO3 (sample 1, black dots). Figure 5d depicts the corresponding first derivative of the sorption (black line) and the ECOS–Runsalt calculation (blue, green and gray lines). The step at 66–68% is obvious in both diagrams. However, the first derivative also shows a change starting at 60% and a small bump with a maximum at 74%. This measurement is well suited to demonstrate that slight changes in the first derivative, which are not recognizable in the sorption curve, can only be successfully identified or assigned to a phase transition if thermodynamic calculations are available for comparison. Thus, in this case the bump at 74% can be assigned to the critical crystallization humidity, while the change at 60% cannot be assigned to any phase transition and its origin is unclear. Consequently, in case of missing comparative calculations or unknown sample compositions the determination of phase transitions including only small changes of the water content is difficult. Anyhow, the phase transitions for dissolution or crystallization that include the largest change in water content can be detected reliably. It is worth mentioning that these transitions are the most relevant considering the evaluation of the risk potential in terms of conservation of cultural heritage.

Next, the results for a sandstone sample impregnated with the same solution (sample SAN-1, red diamonds and red line in Fig. 5c, d, respectively), but investigated in a near equilibrium run (method A), is discussed. In this context it is also necessary to look at a measurement of an empty reference sandstone (SAN-0), also shown in Fig. 5c (green triangles). It is obvious that also the stone itself continuously adsorbs water vapor upon an increasing relative humidity (the sorption and desorption curves of the empty reference stone are also depicted in Fig. S4 of the supplementary material). Consequently, the material also contributes to the sorption curve of the composite. In comparison to the empty material, the impregnated stone shows a more pronounced sorption from about 50% onwards. Fig. S5 in the supplementary material compares the normalized curves in terms of n(H2O)∙w(sample)–1. At low RH, the normalized curve of the reference stone is higher than the curve of the impregnated stone. It is possible that the lower sorption capacity of the impregnated stone in this RH range is the result of a blocking of the small pores (these pores have the highest contribution to the total surface area) by salt crystals impeding the adsorption in the respective pores. In the sorption curve of SAN-1 a significant step starting at 60% and continuing up to 66% can be observed. In the first derivative this is represented by a maximum that is much broader than for the bulk salt mixture in Fig. 5b.

Apart from the continuous sorption by the stone material it also has to be noted that the material has a fraction of small-diameter pores (d < 100 nm). Salts in these small pores show a transition humidity and water uptake already at lower values as the curvature of the meniscus at the vapor-liquid interface shifts the capillary condensation to lower values than the mutual deliquescence of the mixture (Kelvin effect)30. As a result, the mutual deliquescence humidity is shifted to lower RH and the step in the water uptake curve is less steep (and the maximum in the first derivative is broadened), since the deliquescence in different pore sizes happens at different RH. For porous materials there will always be a shift to lower RH because the mutual deliquescence humidity in the large pores equals the bulk value and represents the maximum DRH value. Accordingly, the step for the main phase transition starts below the calculated mutual deliquescence humidity and the pronounced water uptake (compared to the empty stone) already starts at 50%. Above the mutual deliquescence humidity, the first derivative of SAN-1 reveals two more maxima at 69 and 74%, the latter can be attributed to the critical crystallization humidity. The maximum at 69% is in the range of the calculated relative humidity at which KCl dissolves completely. However, as the change in the water content is very small it is not expected that this transition is visible in the DVS. The first derivative shows other maxima below 60% that cannot be assigned to phase transitions when comparing it to the calculated crystallization sequence and whose origin is unclear.

The discussion shows that the properties of the stone matrix may affect the sorption curves (impact of very small pores, maxima of unclear origin and broad steps), but the identification of relevant phase transitions is still accurate in terms of practical considerations for conservation. This is a very important and interesting result for the use of the method in conservation studies. As already pointed out by Rörig-Delgaard14, it is possible to study small real samples of a porous material contaminated with salt, allowing the individual analysis of critical climatic conditions for specific objects.

In addition to the measurement of the impregnated stone under equilibrium conditions, a sample impregnated with the same solution was measured with method B (steps of 2% every 5 h, salt content: 1.1 w.%) to investigate whether phase transitions in the composites can still be observed in more time efficient measurements (see Fig. 6, where the amount of water is normalized to the amount of salt in the stone). Compared to method A, the step of the mutual deliquescence humidity occurs nearly at the same relative humidity. Towards higher relative humidities in the first derivative a broad bump occurs between 70 and 74%. The run with method A included two bumps at 69 and 74%.

Another reasonable question is how a lower salt content affects the measurements. The investigation of a stone sample (sample SAN-2, salt content: 0.28 w.%) impregnated with a more dilute solution of the same relative composition revealed that the steps contrast less with the noise of the first derivative but are still observable (maxima at 60–62%, 68% and 74%, see orange curve in Fig. 6).

Figure 7 depicts results for different mixture compositions in the Na+–K+–Cl––NO3––H2O system (all solutions with an initial total molality of 4 mol∙kg–1) investigated with method B (2% change every 5 h). Mixed solutions 2 and 3 contained 1 mol∙kg–1 KNO3/3 mol∙kg–1 NaCl and 3 mol∙kg–1 KNO3/1 mol∙kg–1 NaCl, respectively. Solutions 4 and 5 contained different amounts of the cations, while the anion composition was constant at 2 mol∙kg–1 Cl– and NO3–. Comparing the sorption curves (Fig. 7a) and the first derivatives with the ECOS predictions (Fig. 7b) for sample 2, it is obvious that the detected transition humidity between 64 and 66% (last data point before the step in the sorption curve and first one within the step) fits the predictions very well. According to ECOS, all salts dissolve within a narrow humidity range (66.5 to 70.5%) which is represented by the broad maximum at 68% of the first derivative and a less sharp step in the sorption curve. The measurement conditions (2% RH every 5 h) resulted in the less sharp maximum not allowing the detection of two separated steps for the mutual deliquescence humidity and the critical crystallization humidity. To exemplarily demonstrate that the measured sorption curves are indeed realistic and that model calculations and measurements are perfectly in line for this salt system also at a hold time of 5 h and 2% increments, Fig. 7 includes a comparison with a sorption curve calculated with the model described in Steiger et al. 11 (a comparison of this model calculation to the ECOS calculation is depicted in Fig. S6 in the supplementary material, showing only minor differences).

a Sorption (black dots) and desorption curves (gray dots) of samples 2, 3 (molar ratios of 3:1 and 1:3 for NaCl to KNO3, respectively) and 4 (molar ratio of 3:1 for Na+ to K+ and 1:1 for Cl– and NO3–) investigated with method B; b corresponding first derivatives of the sorption curves (black curves) and ECOS–Runsalt calculations. a includes a sorption curve calculated with the model of Steiger et al.11 for the mixture composition of sample 2.

For sample 3, the first derivative of the sorption curve reveals a maximum at 66–68%. The mutual deliquescence humidity can be determined to be between 64 and 66% as the mass uptake starts between these two values, in accordance with the value predicted by ECOS (66.5%). However, no obvious maximum in the first derivative nor a step in the sorption curve points to the critical crystallization humidity predicted by ECOS at 88.0%. It is possible that the gradual dissolution of KNO3 hampers the detection of the phase transition in the first derivative. In this case a comparison of the sorption and desorption branches can be helpful. Between 86 and 76%, the two branches are not congruent and show a slight hysteresis (see inset in Fig. 7a, middle), indicating that the sample was in different states at the same relative humidity during sorption and desorption. More specifically, for this sample, there were still crystals present up to 86% upon sorption, but a solution was present until 76% upon desorption due to supersaturation. Consequently, the critical crystallization humidity can be identified from the starting point of the hysteresis (coming from a humid to a dry environment), which is at 86% for this measurement. Considering the error of 2% resulting from the step size, there is agreement between the calculated and experimental critical crystallization humidity.

For the other two mixtures (sample 4, Fig. 7; sample 5 Fig. S7), the first derivatives and the sorption/desorption curves show two distinct steps. For solution 4 (Fig. 7a, right) steps are visible at 62 and 70% (phase transitions start between 60 and 62% and 68 and 70%). There is also a slight change in slope at 64%. This result is in good agreement with the ECOS calculations which give phase transitions at 62, 64 and 68%. For sample 5 the agreement is also very good (see Fig. S7 in the supplementary material). The first derivative shows maxima at 66–68% and 78%. The sorption and desorption branches deviate below 84%, thus, the critical crystallization humidity can be located at this value. The ECOS predictions give almost the same values for phase transitions (67, 77 and 84%).

The reproducibility of the DVS measurements was investigated with a duplicate measurement of a highly hygroscopic salt mixture (sample 6 containing Na+, K+, Ca2+ and NO3–) using method B (RH steps of 2% and hold times of 10 h; red and black dots and curves in Fig. 8a, b). The sorption curves are in good agreement, while the first derivatives show a slight shift of the maxima. In the first run significant maxima in the first derivative were detected at 22% (broad maximum, phase transition starting between 14 and 16%), 34%, 40% and 50–52%; in the second run at 26% (broad maximum, phase transition starting between 20 and 22%), 34–36%, 44% and 50–52%. It is assumed that the steps in both measurements include the same phase transitions, but the position of the maxima may differ due to the stepwise rather than abrupt increase of absorbed water (there is no vertical step in the sorption curves) or kinetic hindrance in the hygroscopic system. The first derivative might indicate a small maximum at 64 and 60%, respectively, which can be refuted by comparing the sorption and desorption curves which only start to diverge at 52% (inset in Fig. 8a left). This example again shows that the comparison of sorption and desorption branches can be helpful for the interpretation of results for more complex salt mixtures.

Although a comparison with ECOS–Runsalt is given for this salt system, it is known that the program does not calculate the correct crystallization pathways for this system, since a double salt (KCa(NO3)3·3H2O) is included, which is not taken into account in ECOS. It is particularly important to consider that the predicted anhydrous calcium nitrate is thermodynamically unstable under the climatic conditions and it does not crystallize at the mutual deliquescence humidity (the drawbacks for some special cases in ECOS have recently been summarized8). Therefore, the ECOS calculations do not provide a reliable comparison at low humidity. According to Charykov et al. 31 the equilibrium crystallization sequence includes the crystallization of NaNO3 and KNO3 nearly at the same time at 53%, complete dissolution of KNO3 and crystallization of KCa(NO3)3·3H2O next to NaNO3 at 42% and the mutual deliquescence humidity at 37%, where NaNO3 and KCa(NO3)3·3H2O) are the crystalline phases. Ca(NO3)2 phases are not included in this equilibrium sequence, however dissociation reactions of the double salt to KNO3 and Ca(NO3)2 phases could take place below 37%. Hence, the meaning of the broad maxima at 22 and 26% in the first and second run, respectively, cannot be assigned to specific phase transitions. In addition, it is possible that the highly hygroscopic phases involved do not crystallize during sample preparation and that the processes in this system do not follow the equilibrium pathway. Instead, metastable phases may be involved. The desorption curve in Fig. 8a also shows that only a partial crystallization was achieved during drying (the amount of absorbed water is higher at low relative humidities during desorption than during sorption), probably due to the hygroscopic character of the involved phases and a kinetic hindrance of their crystallization. Despite these uncertainties regarding the phases precipitating at low relative humidities, it is still possible to detect the phase transitions required for an evaluation in terms of preventive conservation by DVS measurements. It may not be possible to assign or interpret all phase transitions, but the most important information of the critical crystallization humidity can still be obtained, since at this point in the measurement all highly hygroscopic phases involved will have dissolved anyway.

The same solution composition (sample 6) was used to investigate the influence of a different hold time in method B on the detectability of phase transitions. A comparison of the sorption isotherms and the corresponding first derivatives for a measurement with a step size of 2% and hold times of 10 and 5 h is shown in Fig. S8 in the supplementary material. It is obvious that the first step around 30% is stretched over a broader range in the measurement with the shorter hold time, the corresponding maximum in the first derivative is slightly shifted to a higher relative humidity (30% instead of 26%, also the second maximum is slightly shifted). For the phase transitions at 44% and 50%, a very good agreement was found for both hold times, indicating that the shorter hold time of 5 h can be used to estimate the critical crystallization humidity as accurately as the hold time of 10 h.

Essentially, the resolution of phase transitions should improve with a longer hold time and their localization should be facilitated as the sample has more time to equilibrate with the surrounding. As can be extracted from the sorption curve and the first derivative of a method A run of sample 6 in Fig. 8 (middle diagrams), the opposite is the case. There are only three obvious steps that can be extracted from both representations (maxima at 16%, 37% and 50–52%; the inset in Fig. 8a shows the deviation of sorption and desorption branches for \(\varphi\)<53%). No other maxima can be extracted from the first derivative, as it shows significant noise and therefore many small maxima. Consequently, the equilibrium measurement gives differences for the RH in case of transitions below the critical crystallization humidity (the latter agrees with the values determined in the measurements with shorter hold times), since it better reflects the equilibrium pathway. Apart from that, it does not give additional information and the evaluation of the sorption curve becomes more feasible under a shorter hold time as the steps and maxima in the first derivative are more pronounced.

For the salt mixture within a specimen of Sand sandstone (sample SAN-3, Fig. 8a, b, right images) investigated with method B (2% steps and a hold time of 5 h), at first glance, phase transitions are less obvious than for bulk samples. The first derivative allows the detection of a very broad maximum between 4 and 20% and more narrow transitions with maxima at 40% and 52%, the latter being in perfect agreement with values detected for bulk samples investigated with method B (2% steps and a hold time of 10 or 5 h), again underlining the applicability of the method to investigate salt-contaminated porous materials. The discrepancy of the phase transitions at lower humidity can again be a result of the pore size effect already explained for SAN-1. It is also possible that a different crystallization behavior within the porous host with nucleation sites favoring the crystallization of hygroscopic phases during drying after impregnation contributes to the discrepancies.

Investigation of more complex salt mixtures

To expand the investigations towards more complex salt systems, an equimolar mixture containing Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl– and NO3– ions (sample 7) was also measured in duplicate (Fig. 9a, b). In the first measurement, steps or maxima were detected at 20–22%, 30%, 36%, 46% and 58%. In the second measurement they were almost the same (20–22%, 28%, 34%, 46% and 58%). A comparison to ECOS predictions reveals that the critical crystallization humidity is in very good agreement. The phase transition at 46% can also be correlated to the ECOS calculations. However, it is not possible to determine whether the phases involved are those predicted by the model.

The same applies for sample 8 which is an equimolar mixture containing all six ions (Fig. 9). In a duplicate measurement with method B (relative humidity steps of 2% and a hold time of 10 h) again almost identical courses were obtained (Fig. 9a, b, middle images). In the experiment, steps were detected at 20% (or 16% in the second run, very broad), 30–32% and 48–50%. While the critical crystallization humidity of 48–50% is in satisfactory agreement with the value predicted by ECOS, no other correlations can be found. In a method A run of sample 8 maxima were detected at 31% and 49% (neglecting steps around 20%), exactly in the middle of the detected ranges in the method B runs (Fig. 9a, b, right images). Compared to the method A measurement of sample 6, the maxima are better visible for this sample. As described earlier, an equilibrium run better reflects the equilibrium pathway and transition humidities will be more accurate. However, comparing the deviations and the measurement times it can be concluded that the much more time-consuming method A does not give additional information necessary for answering questions with regard to critical crystallization humidities for salt contaminated built heritage.

For the samples 7 and 8 (multiple) steps around 20% are visible, but, as already mentioned for sample 6 with even less ions, the crystallization pathway is unclear, especially at low RH. Also in these mixtures it is possible that not all salts precipitated completely during drying at 60 °C and additional phases not involved in the ECOS model may be included. Also for these samples the desorption branch shows only partial crystallization upon drying and supersaturation (see insets).

Conclusions

The presented measurements and optimized methods show that the DVS is highly suitable to obtain meaningful results for the conservation of built heritage. The most interesting values, such as the critical and mutual crystallization/dissolution humidities, can be determined accurately. It was shown that the accuracy of the determined values depends on the used relative humidity increment and, in case of high sample masses, also on the hold time. The detection of deliquescence for single salts is possible from the sorption curve, as only one phase transition associated with a large mass change occurs (in case of salts without different hydrated phases). For salt mixtures, not all phase transition may be accompanied by a water uptake visible in the sorption curve. The first derivative and the comparison of the sorption and desorption branch are helpful for the interpretation. The first one gives the relative humidity at which the mass change is largest and the latter one reveals the critical crystallization humidity if not already detectable from the first derivative. In mixtures, salts crystallize within a range of the relative humidity and for impregnated stone samples the matrix and small pores may influence the sorption behavior, both leading to less sharp steps or broad maxima in the sorption curve and its first derivative. For some mixtures, the first derivative may show several small local maxima, that impede the assessment whether a phase transition is involved. Then, in case of unknown samples or missing thermodynamic calculations, only very pronounced steps or maxima should be evaluated. Regarding this, it should be highlighted that in the context of conservation, phase transitions that involve large amounts of salt are the most relevant.

Regarding the investigated hold times, the measurements revealed that for small sample masses a time efficient hold time of 5 h allows a sufficiently accurate determination of the transition humidity. For some mixtures it was shown that faster DVS runs led to better detectable steps, making the method more attractive for the study of real samples. With relative humidity steps of 2% and a hold time of 5 h from 0 to 95%, 23 samples can be investigated within three weeks in a complete run or within 1.5 weeks if only sorption is investigated. Although the phase transition values may be less accurate at a faster rate, they are perfectly adequate for use in the conservation practice, where the aim is to maintain a relative humidity range where crystallization cycles are avoided, which can be clearly determined from the measurements. In addition, it has been shown that the method can be used not only to investigate lab-prepared salt mixtures in order to study the deliquescence of poorly investigated salt mixtures, but also to determine the critical relative humidity values of salts enriched in porous host materials.

For the salt mixtures, measurements and ECOS calculations are in good agreement for the critical crystallization humidity, even for the most complex mixtures. For phase transitions occurring between the mutual deliquescence humidity and the critical crystallization humidity it is not always possible to assign them to the predicted phases, either because the model calculations do not include or correctly predict all phases involved, or, because not all the phases of the sample have crystallized during sample preparation. With regard to the latter, it should be noted that despite possibly kinetically hindered crystallization of hygroscopic phases, the transitions relevant to the studied context can be observed, since these phases would have already dissolved at the critical crystallization humidity. The fact that critical humidity ranges for mixtures whose crystallization processes are unclear can be determined using this method should be emphasized here as a particular advantage.

Overall, the results are encouraging for the use in preventive conservation and for the more detailed investigation of complex salt mixtures. The data obtained are very helpful and can be used as an alternative or as complementary to the determination of ion contents in the specific analysis of salt-contaminated building materials. They are characterized by high accuracy and reproducibility, low effort using fully automatic equipment and very useful information for preventive conservation. Therefore, the method can be used more widely in the future to study both real samples and prepared salt mixtures (in different materials) and to compare the sorption behavior of the latter with model calculations. An extension of the method to include Raman spectroscopy should provide additional information on phase transitions, so that the comparison with the ECOS calculations can be made in more detail.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Steiger, M. Crystal growth in porous materials—I: The crystallization pressure of large crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 282, 455–469, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2005.05.007 (2005).

Price C. A., editor. An expert chemical model for determining the environmental conditions needed to prevent salt damage in porous materials: Protection and conservation of the European cultural heritage; project ENV4-CT95-0135 (1996-2000) final report. London: Archetype; 2000.

Steiger, M. Salts in porous materials: Thermodynamics of phase transitions, modeling and preventive conservation. Resto. Build. Monum. 11, 419–432, https://doi.org/10.1515/rbm-2005-6002 (2005).

Wang, S., Stahlbuhk, A. & Steiger, M. Hydration and deliquescence behavior of calcium chloride hydrates. Fluid Ph. Equilib. 585, 114171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fluid.2024.114171 (2024).

Charola, A. E., Pühringer, J. & Steiger, M. Gypsum: a review of its role in the deterioration of building materials: A review of its role in the deterioration of building materials. Environ. Geol. 52, 339–352, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-006-0566-9 (2007).

Arnold, A. & Zehnder, K. Monitoring wall paintings affected by soluble salts. In: Cather, S. (ed.). The conservation of wall paintings: Proceedings of a symposium organized by the Courtauld Institute of Art and the Getty Conservation Institute, London, 1987, 2nd ed. (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute; 1996) p. 103–135.

Steiger, M., Charola, A. E. & Sterflinger K. Weathering and deterioration. In: S. Siegesmund, R. Snethlage, editors. Stone in Architecture. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014) p. 225–316.

Godts, S. et al. Modeling salt behavior with ECOS/RUNSALT: Terminology, methodology, limitations, and solutions. Heritage 5, 3648–3663, https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040190 (2022).

Price, C. A. & Brimblecombe, P. Preventing salt damage in porous materials. Stud. Conserv. 39, 90–93, https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.1994.39.Supplement-2.90 (1994).

Pitzer, K. S. Ion interaction approach: theory and data correlation: Chapter 3. In: K. S. Pitzer, editor. Activity Coefficients in Electrolyte Solutions. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. p. 75–153.

Steiger, M., Kiekbusch, J. & Nicolai, A. An improved model incorporating Pitzer’s equations for calculation of thermodynamic properties of pore solutions implemented into an efficient program code. Const. Build. Mater. 22, 1841–1850, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.04.020 (2008).

Bionda, D. Modelling indoor climate and salt behaviour in historic buildings: A case study. [Dissertation]. Zürich, Switzerland: ETH Zürich; 2006.

Rörig-Dalgaard, I. Direct measurements of the deliquescence relative humidity in salt mixtures including the contribution from metastable phases. ACS Omega 6, 16297–16306, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c00538 (2021).

Rörig-Dalgaard, I. Potential salt damage assessment and prevention based on micro samples. In: Lubelli B, Kamat A, Quist W, editors. Proceedings of SWBSS 2021. Fifth International Conference on Salt Weathering of Buildings and Stone Sculptures, Delft University of Technology, 22–24 September 2021, Delft, the Netherlands. Delft: TU Delft Open; 2021. p. 21–30.

Rörig-Dalgaard, I. & Svensson, S. High accuracy calibration of a dynamic vapor sorption instrument and determination of the equilibrium humidities using single salts. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 54101, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4949513 (2016).

Franzen, C. & Mirwald, P. W. Moisture content of natural stone: static and dynamic equilibrium with atmospheric humidity. Environ. Geol. 46, 391–401, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-004-1040-1 (2004).

Franzen, C. & Mirwald, P. W. Moisture sorption behaviour of salt mixtures in porous stone. Geochemistry 69, 91–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemer.2008.02.001 (2009).

Godts, S. et al. Charge balance calculations for mixed salt systems applied to a large dataset from the built environment. Sci. Data. 9, 324, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01445-9 (2022).

Maguregui, M. et al. Analytical diagnosis methodology to evaluate nitrate impact on historical building materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391, 1361–1370, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-008-1844-z (2008).

Siedel, H., Pfefferkorn, S., von Plehwe-Leisen, E. & Leisen, H. Sandstone weathering in tropical climate: Results of low-destructive investigations at the temple of Angkor Wat, Cambodia. Eng. Geol. 115, 182–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2009.07.003 (2010).

Diaz Gonçalves, T. Salt Decay and salt mixtures in the architectural heritage: A review of the work of Arnold and Zehnder. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 18, 125–149, https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2022.2117670 (2024).

Godts, S. et al. Salt mixtures in stone weathering. Sci. Rep. 13, 13306, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40590-y (2023).

Lubelli, B., van Hees, R. & Brocken, H. Experimental research on hygroscopic behaviour of porous specimens contaminated with salts. Constr. Build. Mater. 18, 339–348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2004.02.007 (2004).

Nunes, C., Skružná, O. & Válek, J. Study of nitrate contaminated samples from a historic building with the hygroscopic moisture content method: Contribution of laboratory data to interpret results practical significance. J. Cult. Herit. 30, 57–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2017.09.013 (2018).

Godts, S., Hayen, R. & de Clercq, H. Investigating salt decay of stone materials related to the environment, a case study in the St. James church in Liège, Belgium. Stud. Conserv. 62, 329–342, https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2016.1236997 (2017).

Diaz Gonçalves, T. & Delgado Rodrigues, J. Evaluating the salt content of salt-contaminated samples on the basis of their hygroscopic behavior. Part I: Fundamentals, scope and accuracy of the method. J. Cult. Herit. 7, 79–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2006.02.009 (2006).

Diaz Gonçalves, T. & Delgado Rodrigues, J. Evaluating the salt content of salt-contaminated samples on the basis of their hygroscopic behaviour: Part II: experiments with nine common soluble salts. J. Cult. Heritage. 193–200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2006.03.002 (2006).

Stahlbuhk, A. & Steiger, M. Damage potential and supersaturation of KNO3 and its relevance in the field of salt damage to porous building material. Constr. Build. Mater. 325, 126516, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126516 (2021).

Schäfer, M. & Steiger, M. A rapid method for the determination of cation exchange capacities of sandstones: preliminary data. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 205, 431–439, https://doi.org/10.1144/gsl.sp.2002.205.01.31 (2002).

Talreja-Muthreja, T., Linnow, K., Enke, D. & Steiger, M. Deliquescence of NaCl confined in nanoporous silica. Langmuir 38, 10963–10974, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c01309 (2022).

Charykov, N. A., Puchkov, L. V. & Ramaia Gonzalez, N. V. Phase equilibria in the Na+, K+, Ca2+, NO3—H2O system at 25 °C. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 37, 346–349 (1992).

Acknowledgements

A.S. and M.S. are grateful for financial support by the German Research Foundation (Grant No. STE 915/8–1). We acknowledge financial support from the Open Access Publication Fund of Universität Hamburg.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S., S.G. and M.S.: conceptualization, methodology, validation; A.S.: Investigation, writing (original draft), visualization; S.G. and M.S.: Writing (review and editing); M.S.: Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stahlbuhk, A., Godts, S. & Steiger, M. Dynamic water vapor sorption: a helpful tool for preventive conservation of salt contaminated built heritage. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 31 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01548-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01548-7