Abstract

Numerous tremolite jade artifacts from archaeological sites exhibit powdering damage, necessitating immediate consolidation. However, research on jade consolidants remains limited. Siloxane is a promising material, yet its effectiveness is hindered by high levels of non-silicate components, such as calcium and magnesium, in tremolite. In this study, mercapto-functionalized siloxane sols with varying mercapto group contents were synthesized via sol–gel chemistry using (3-mercaptopropyl) trimethoxysilane (MPTS), (3-aminopropyl) dimethoxymethylsilane (APDMOS), and tetraethoxysilane (TEOS). Their consolidation effects on tremolite jade were evaluated. Results showed that mercapto-functionalized siloxane exhibited stronger performance than non-functionalized siloxane. This improvement stems from its dual functionality: alkoxy groups undergo hydrolysis and polycondensation to form highly polymerized xerogels that fill microvoids, while thiol groups (–SH) coordinate with calcium and magnesium ions in tremolite, acting as a functional “glue” to bind particles. Mercapto-functionalization thus offers a promising strategy to optimize jade consolidation and improve compatibility with non-silicate substrates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the early Neolithic Age (ca. 9000 BP), jade has been utilized for crafting decorative, ritualistic, and burial objects, becoming a key cultural symbol in ancient China. Jade artifacts unearthed from archaeological sites often show signs of deterioration, which can result from both natural weathering and human interference1,2. Such deterioration can lead to notable alterations in physical properties, including color, density, and hardness3,4. In severe cases, jade artifacts subjected to extensive powdering may experience a loss of structural integrity. Consequently, consolidation treatments are crucial, whether applied in situ during excavation to prevent further damage or in restoration laboratories to restore the structural cohesion and unity of the artifacts, thereby ensuring their long-term preservation.

Acrylic resins, despite their frequent use in jade conservation, have been found to generally exhibit poor compatibility with inorganic materials and limited durability5,6. On the other hand, ethyl silicate is widely favored for consolidating silicate-based artifacts because of its beneficial characteristics, such as low viscosity, excellent chemical stability, and the ability to chemically bond with silicate materials7,8,9,10. These traits enable ethyl silicate to infiltrate the porous structure of the artifact, forming a silica gel that reinforces loose mineral particles and significantly boosts the overall strength of the artifact11,12. Despite these advantages, several limitations hinder its application in conservation. First, it can form a dense, microporous gel network that is prone to brittleness and cracking13,14. The second is the lack of proper bonding to nonsilicate surfaces15,16,17. To address these limitations, several approaches have been proposed, including regulating the molecular structure with organic fragments18,19,20,21,22,23 and incorporating particles and surfactants (e.g., SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, Ca(OH)2 and n-octylamine, etc.)15,16,24,25,26,27. However, most of these methods were originally developed for the conservation of stone buildings and may not be directly applicable to jade artifacts.

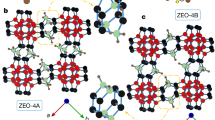

Currently, research on consolidant specifically designed for the conservation of tremolite jade remains limited, creating a significant gap in the field. Developing effective consolidant is crucial for ensuring the preservation of these valuable artifacts. We have previously synthesized a hybrid siloxane oligomer for jade artifacts conservation28, which features a unique flexible-rigid structure, forms xerogels with lower crack density than ethyl silicate, and shows promise in consolidating powdered tremolite jade artifacts. However, its consolidating performance on tremolite jade (Ca₂Mg5[Si4O11]2(OH)2) remains limited, as a significant portion of the mineral’s structure comprises nonsilicate components. Tremolite’s crystal structure predominantly comprises double-chain silicate tetrahedra, stabilized by interstitial layers of calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) ions, which reinforce the silicate chains through essential structural connections29. Theoretically, calcium and magnesium account for approximately 13.81% and 24.81% of the mineral’s weight as CaO and MgO, respectively30. Due to the absence of chemical bonding between silica-based consolidants and these nonsilicate components, the consolidation effect is constrained. If additives capable of acting as coupling agents between silica-based consolidants and the nonsilicate components of tremolite could be introduced, this limitation might be overcome. However, this remains a considerable challenge.

The functionalization of siloxanes provides a promising approach for our research. Thiol-containing siloxanes, such as (3-mercaptopropyl) trimethoxysilane (MPTS), have shown great promise in the conservation of both metal31 and wooden32,33 artifacts. Their effectiveness is attributed to their dual functional groups: the silane group (–Si(OCH3)3) and the thiol group (–SH). In metal artifact conservation, MPTS forms a protective network through the condensation of silanol groups (Si–OH) after hydrolysis. Additionally, chemisorption via metal thiolate (Me–S–C) and metal siloxane (Me–O–Si) bonds ensures strong adhesion to the metal substrates34,35,36. Tests, including NaCl immersion and acid rain simulations, demonstrate its excellent corrosion resistance on bare, pre-patinated, and gilded copper surfaces37,38. In the conservation of waterlogged wood, researchers have assessed various organosiloxanes with different functional groups and found that MPTS provides the best dimensional stability, achieving a shrinkage reduction of up to 98%32. This high efficacy is attributed to the thiol groups in MPTS, which form stable thioether bonds with quinone methide intermediates generated from lignin hydrolysis, while its Si–OH groups bond with cellulose hydroxyls39. These interactions reinforce the wood’s structural integrity, enhancing dehydration efficiency and dimensional stabilization.

Building on the promising applications of thiol-containing siloxanes, we aimed to introduce thiol groups into siloxane-based consolidant to enhance its compatibility and bonding with the nonsilicate components in tremolite jade artifacts. In this study, a novel mercapto-functionalized siloxane was synthesized via sol–gel chemistry using MPTS, (3-aminopropyl) dimethoxymethylsilane (APDMOS), and tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) as precursors. The molecular structure of the synthesized siloxane was characterized using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Subsequently, various techniques were employed to evaluate the effectiveness of the consolidants, including color variation test, open porosity test, contact angle measurement, peeling test, and hardness test. Furthermore, the consolidation mechanism was analyzed in detail using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

Methods

Materials

MPTS (99%) and APDMOS (97%) were procured from Adamas-beta. TEOS (98%) and ethanol (EtOH, 99%) were supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Deionized water (H2O) was prepared using a Millipore Milli-Q purification system. Blocks of nephrite jade were sourced from Xinjiang, China, and identified as primarily composed of tremolite through X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyses. XRD results showe that the diffraction peaks match those of tremolite (PDF# 44-1402, Supplementary Fig. 1), and XRF analysis further confirms this, with a Mg/(Mg + Fe) ratio of 0.95 (Supplementary Table 1).

Preparation of the mercapto-functionalized consolidants

Five consolidants with varying MPTS contents were prepared by stirring mixtures of MPTS, APDMOS, TEOS, EtOH, and H₂O in a specific molar ratio at 70 °C for 10 h. Deionized water was used for the hydrolysis reaction, while EtOH acted as the solvent. The compositions and corresponding names of these consolidants are listed in Table 1. Among them, MAT0 is a hybrid siloxane previously developed for the conservation of jade artifacts28, while MAT0.5, MAT1, MAT1.5, and MAT2 are mercapto-functionalized siloxanes developed based on this formulation. The xerogels were formed by drying the sols in glass Petri dishes.

Preparation of the simulated powdered jade sample and consolidating treatments

Simulated powdered jade samples were prepared using the previously described method28. This approach not only avoids the risk of damaging the jade artifacts during consolidation but also ensures the consistency of the samples in terms of size, physical properties, and other characteristics, which is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of the consolidation treatments. In this process, nephrite jade blocks were mechanically ground into a fine powder, which was then sieved to obtain a uniform particle size distribution. The powder was then compressed under a constant pressure of 8 MPa using a tablet press to fabricate cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 13 mm and a thickness of 1.5 mm.

To ensure consistent treatment, each consolidant was diluted to a 5% solid concentration and applied to the jade samples by brushing until full saturation. Afterward, the samples were stored in a controlled environment (25 °C and 50% relative humidity) until they reached a constant weight. The treated specimens were labeled as “Tre-MAT0,” “Tre-MAT0.5,” “Tre-MAT1,” “Tre-MAT1.5,” and “Tre-MAT2,” with the untreated sample serving as the control, referred to as “Tre-REF” (where “Tre” stands for the first three letters of “Tremolite”).

Characterization of jade and consolidants

The jade samples utilized in this study were characterized using XRD and XRF to determine their mineral composition. XRD analysis was performed with a Rigaku MiniFlex 600 X-ray diffractometer, employing Cu Kα radiation. XRF analysis was conducted using an M4 Tornado µXRF spectrometer (Bruker Nano GmbH, Berlin, Germany), which was equipped with a 30 W Rhodium (Rh) tube.

The molecular structures of the consolidants were analyzed using FT-IR and 29Si solid-state NMR spectroscopy. FT-IR spectroscopy was performed using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer equipped with an ATR sampling accessory. 29Si solid-state NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 MHz spectrometer at 79.49 MHz, with a 2 s relaxation delay and 2048 scans per measurement.

Assessment of consolidation treatments

Colour variation test

Color variations (ΔE) of the sample following consolidation were quantified using a spectrophotometer (3nh YS3010, Shenzhen, China). The color parameters L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness) in the CIELAB color space were evaluated. For each treatment condition, the average of three measurements was considered. ΔE was then calculated using the Eq. (1):

Open porosity test

Open porosity refers to the percentage of the volume of open pores relative to the apparent volume of the sample. It can be determined using the Eq. (2)40:

where ms represents the weight of the sample when fully saturated, mh is the weight of the sample while submerged in water, and md refers to the dry weight of the sample.

Static contact angle test

The static contact angle was measured using an Attension® Theta Flex system (Biolin Scientific), which was coupled with a NAVITAR high-resolution lens for precise real-time measurements. During the test, five water droplets were randomly placed on each sample, and the average contact angle was recorded.

Mechanical performance test

The peeling test was conducted to evaluate the surface cohesion of the samples41, based on methodologies described in previous research42,43. A segment of Scotch tape was applied to the surface and pressed for several minutes. It was then removed at a constant speed using tweezers, and its weight was measured with a precise balance. This process was repeated ten times at the same location, using a new piece of tape each time. Surface adhesion was quantified by measuring the mass of detached powder, and the cumulative mass loss per unit area was calculated using the Eq. (3):

where “weight peeled” refers to the total loss in weight per unit area after k cycles of taping. The initial mass of the adhesion test strip before the ith test is denoted as mi0, and mi is the final mass of the strip after the ith test. A represents the area of contact between the test strip and the surface of the sample.

The surface hardness of the samples, prior to and following consolidation, was determined using a Leeb Hardness Tester (Leeb 180D, Chongqing Libo Instrument Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China). Five measurements were taken for each sample, and the average value was used to represent the surface hardness.

Morphological characterization

The changes in the microstructure of the jade samples before and after consolidation were analyzed using a SEM (Phenom XL, FEI Electron Optics BV, Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

XPS analysis

XPS was employed to analyze surface changes in the jade samples before and after consolidation. The measurements were conducted using a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-alpha spectrometer, with monochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) as the X-ray source. All spectra were calibrated to the neutral carbon peak at 284.8 eV.

Results and discussion

Effect of introducing MPTS in sols

During the design and preparation stages of the consolidant, an initial screening process should be employed to quickly eliminate mixtures that exhibit undesirable phenomena, such as silica precipitation, phase separation, rapid gelling, or other issues that would render the sols unsuitable for use as consolidants for artifacts13. For consolidants intended for jade artifacts, it is crucial that the mixture remain in a stable liquid form to facilitate application by brushing or spraying. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, the sols of MAT0, MAT0.5, and MAT1 remained transparent throughout the preparation process and retained this transparency in their final state. As the MPTS content increased, the MAT1.5 sol transitioned from transparent to slightly cloudy while maintaining good fluidity. Moreover, during preparation and stirring, the MAT2 sol underwent whitening and gelation, which rendered the sol unsuitable for artifact consolidation and necessitated its immediate exclusion from further consideration.

Characterization of consolidants

The molecular structures of the three raw monomers and the resulting consolidant xerogels were characterized using FT-IR spectroscopy, with the corresponding results presented in Fig. 1. The FT-IR spectra of APDMOS, MPTS, and TEOS exhibit absorption bands in the ranges of 1160–1200 cm−1, 1000–1100 cm−1, and 770–820 cm−1, respectively, which are attributed to the Si–O–C bonds44,45,46. The FT-IR spectrum of the resulting AMT0 xerogel showes characteristic Si–O–Si absorption bands at around 1007 cm−1, corresponding to the hydrolysis and condensation of APDMOS and TEOS. In the FT-IR spectra of AMT0.5, AMT1, and AMT1.5 xerogels, this band shifts to 1023 cm−1, indicating the successful incorporation of MPTS and its copolymerization with the other two siloxanes. Moreover, the absorption bands of Si–O–C bonds in the range of 770–820 cm−1, observed in all three monomers, disappear, and the Si–O–Si symmetric stretching vibrations observed at 795 cm−1 in all xerogels further confirm the hydrolysis and condensation processes of the monomers.

The 29Si solid-state NMR results provide additional qualitative information regarding the molecular structure of the xerogels. As shown in Fig. 2, all xerogels exhibit peaks at approximately δ (29Si) −22 ppm, –100 ppm, and –110 ppm, corresponding to the D2 ((SiO)2SiR2) units, Q3 ((SiO)3Si(OH)) units and Q4 (Si(OSi)4) units20,47,48, which arise from the hydrolysis and condensation of APDMOS and TEOS, respectively. In the spectra of MAT0.5, MAT1, and MAT1.5, a characteristic peak appears at –68 ppm, corresponding to T3 ((SiO)3SiR)48, which results from the hydrolysis and condensation of MPTS. These results confirm the successful copolymerization of the three siloxanes. Notably, as the MPTS content increases, the ratio of Q3 to Q4 changes, further confirming the variation in the degree of condensation (DC) of the TEOS49. The DC is calculated using the peak area ratio of the silicon units, as follows50:

where Qn represents the peak area of the Qn unit, and Q denotes the sum of the peak areas of all Qn units. The peak fitting curves for the Q unit signal peaks of the xerogels are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The areas of the different types of Q unit signal peaks and the calculated values of the DC are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The DC values for AMT0, MAT0.5, MAT1, and MAT1.5 are calculated to be 88.01%, 90.42%, 91.17%, and 92.06%, respectively, indicating that the increase in MPTS content enhances the degree of cross-linking of TEOS in the xerogels.

Based on the aforementioned results, the formation mechanism of the mercapto-functionalized siloxane can be delineated as illustrated in Fig. 3. Initially, the amino groups in APDMOS serve as basic catalysts, accelerating the hydrolysis and condensation of the three siloxane monomers, thus promoting the formation of an oligomeric sol10. In the subsequent solidification process, as the solvent (ethanol) evaporates, further hydrolysis and condensation reactions occur between the oligomers, ultimately leading to the formation of xerogels with a mercapto-functionalized siloxane network structure.

Assessment of consolidation treatments

The color variations of the treated samples were systematically evaluated and are presented in Fig. 4. A consistent trend is observed across all treated samples: a decrease in L* values and an increase in a* and b* values, indicating the samples became darker, redder, and more yellow. The ΔE values for Tre-MAT0, Tre-MAT0.5, and Tre-MAT1 were 3.87, 4.17, and 4.31, respectively, all below 5, suggesting that the color changes are subtle and not readily apparent to the naked eye51,52. However, the MAT1.5 treatment resulted in a ΔE >5, which is deemed unacceptable for artifact conservation.

The evaluation of open porosity in the samples provides critical insights into the performance of the consolidants. As presented in Table 2, Tre-REF displays a porosity of 32.44%. Treatment with MAT0 results in a substantial reduction in porosity to 16.82%, representing a decrease of approximately 48% compared with the untreated sample. Furthermore, the application of MAT0.5, MAT1, and MAT1.5 led to even greater porosity reductions, achieving values of 15.47%, 15.03%, and 14.47%, respectively. These correspond to porosity decreases of 52.31%, 53.67%, and 55.39%. Such reductions indicate that the consolidants effectively penetrate the pore structures, filling the voids and thereby enhancing the consolidation of the jade samples. These findings highlight the effectiveness of the consolidants in improving the structural integrity and overall consolidation of the treated specimens40.

The hydrophilic characteristics of the samples were examined by measuring the static water contact angles (WCAs). As shown in Fig. 5, the untreated Tre-REF sample has a contact angle of 21°, classifying it as hydrophilic. After consolidation with MAT0, the WCA increases to 80°, likely due to the formation of a dense siloxane gel that fills the pores and alters surface properties. Additionally, the hydrophobicity was influenced by residual ethoxy groups in TEOS and methyl groups in APDMOS, both contributing to the increased contact angle8,16. As the MPTS content increased, the WCA slightly decreases, with values for Tre-MAT0.5, Tre-MAT1, and Tre-MAT1.5 samples being 71°, 67°, and 64°, respectively. This behavior is likely a result of the formation of a more compact surface film, which reduces surface roughness and consequently decreases wettability43. Additionally, the hydrolysis of MPTS leads to an increase in the number of hydrophilic silanol groups in the system, further enhancing its hydrophilicity.

The consolidation efficacy was assessed through both surface hardness evaluations and peeling resistance tests. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the surface hardness measurements reveal a marked enhancement in hardness values following consolidation treatments. Specifically, an increase in MPTS concentration corresponds with progressively higher hardness, with the Tre-MAT1.5 sample achieving the highest hardness of 213 HL, representing a 151% improvement from the initial 85 HL. Furthermore, the peeling test results depicted in Fig. 6b demonstrate that cumulative peeling weights tended to rise with each successive test at the same location. Tre-REF shows a cumulative peeling weight of 22.5 mg/cm2. Treatment with MAT0 reduces this value to 11.3 mg/cm². As the MPTS content increased, the cumulative peeling weight continues to decline, reaching a minimum of 7.6 mg/cm2 for the Tre-MAT1.5 sample, which corresponds to a 66.2% reduction compared to the untreated reference. These outcomes indicate a significant reinforcement in the bonding strength between tremolite particles43. The alignment of results from both surface hardness and peeling tests corroborates the effectiveness of MPTS incorporation in enhancing consolidation performance.

Mechanism of consolidation

Based on the preceding analysis, the MAT1 sol demonstrated the most effective consolidation by enhancing the physical properties and mechanical performance of the samples while maintaining color variation within acceptable limits. To gain further insight into the underlying consolidation mechanism, the Tre-MAT1 sample was examined using SEM and XPS.

The microstructural changes after the consolidation treatment were examined by SEM. In the untreated reference sample (Fig. 7a), the tremolite matrix displays a fractured morphology characterized by extensive interparticle cracks and irregularly distributed voids, indicative of weak interfacial bonding and poor mechanical stability. In contrast, the consolidated sample (Fig. 7b) reveals the formation of a smooth and continuous xerogel layer, which uniformly encapsulates the tremolite particles. This xerogel layer effectively bridges the gaps between the particles, leading to an enhanced structural cohesion. The presence of the xerogel layer significantly improves the material’s overall integrity by minimizing the voids and cracks. Figure. 7c–h shows the EDS mapping images of Tre-MAT1, where Ca and Mg originate from the tremolite, while Si is detected in both the tremolite and the xerogel. The S and N signals are attributed to the thiol and amine groups within the xerogel. The homogeneous distribution of S and N elements in the EDS mapping images further supports the successful formation and uniform distribution of the xerogel within the tremolite particles. Simultaneously, optical microscopy images (Supplementary Fig. 4) reveal that the consolidant successfully forms a protective layer over the surface morphology of the specimens.

The XPS technique was employed to further investigate the consolidation mechanism of mercapto-functionalized siloxane. XPS survey scans of the Tre-REF (Fig. 8a) indicate the presence of Mg, Si, Ca, and O. After the consolidation treatment, new peaks are observed at 163.08 and 399.08 eV, attributed to the S2p and N1s core levels, respectively53. These new features indicate the successful formation of xerogels on the surface of the tremolite particles. Concurrently, the signals of Ca and Mg are significantly attenuated in XPS spectra of Tre-AMT1, further suggesting that the tremolite surface is covered by the xerogels (as observed in the SEM images)54.

The high-resolution XPS spectra of Mg1s and Ca2p in the Tre-REF and Tre-AMT1 samples were analyzed to further investigate surface changes. In the Mg1s spectrum (Fig. 8b), the main peak at approximately 1303.88 eV shifts slightly to a lower binding energy after treatment, and a new shoulder peak appears at approximately 1302.68 eV. Similarly, in the Ca2p spectrum (Fig. 8c), the spin–orbit split peaks at around 351.18 eV (Ca2p1/2) and 347.38 eV (Ca2p3/2) exhibit a slight shift to lower binding energies after treatment, and new shoulder peaks appear at 350.18 and 346.88 eV. These spectral changes imply alterations in the local environment of the surface atoms55, likely due to coordination interactions between the thiol group (–SH) and both calcium and magnesium ions. The sulfur atom within the thiol group exhibits strong nucleophilicity, enabling coordination with calcium and magnesium ions through its lone pair electrons. This coordination enhances the interfacial interactions between the consolidant and the tremolite surface, thereby improving interfacial adhesion. Consequently, the consolidant acts as a functional “glue,” as shown in Fig. 9, effectively binding tremolite particles together.

Notably, although the obtained consolidant demonstrates good effectiveness, its durability and re-treatability are essential for practical applications. Siloxane materials are known to undergo catalytic and thermal degradation under harsh conditions56,57,58. Similarly, the siloxane consolidant may experience comparable issues when exposed to improper storage environments. Consequently, we plan to investigate the aging mechanisms of the consolidant under selected storage conditions and explore improved solutions to ensure the long-term preservation of jade artifacts. Additionally, based on the degradation products, we will explore potential methods for further treatment that prevent secondary damage to the artifacts.

In this study, mercapto-functionalized siloxane sols with varying mercapto group contents were synthesized as consolidants for the conservation of tremolite jade artifacts. FT-IR and 29Si solid-state NMR analyses reveal that the alkoxy groups present in the three siloxane monomers undergo hydrolysis and condensation reactions, resulting in the formation of highly polymerized siloxane xerogels. Multiple assessments show that mercapto-functionalized siloxane exhibits superior consolidation effectiveness for powdered tremolite jade artifacts compared to non-functionalized siloxane. Specifically, the sol with a molar ratio of 1MPTS: 1APDMOS: 1TEOS demonstrates excellent consolidation performance, including reduced sample porosity, enhanced surface hardness, and increased adhesion between powdered tremolite particles, with color variation remaining within acceptable limits (ΔE < 5). Additionally, SEM and XPS analyses provide insights into the consolidation mechanism of mercapto-functionalized siloxane sols. These sols form xerogels that fill the pores of the sample, while the coordination of thiol groups with calcium and magnesium ions further strengthens the interfacial adhesion between the consolidant and tremolite, thereby effectively consolidating the jade artifacts.

Mercapto-functionalization of siloxane represents a promising strategy for developing enhanced consolidation treatments for tremolite jade artifacts. Furthermore, this modification enhances the chemical compatibility of silicon-based consolidants with non-silicate substrates, suggesting its potential to improve the effectiveness of conservation treatments for silicate-based artifacts containing non-silicate components.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Chen, Y., Wang, R. & Ji, M. Nondestructive nonlinear optical microscopy revealed the blackening mechanism of ancient Chinese jades. Research 6, 0266 (2023).

Mai, Y., Wang, R. & Cui, H. Study on the blackening mechanism of buried cinnabar within ancient Chinese jades. J. Cult. Herit. 49, 164–173 (2021).

Wang, R. Progress review of the scientific study of Chinese ancient jade. Archaeometry 53, 674–692 (2011).

Zhang, K. et al. Corrosion analysis of unearthed jade from Daye Zhen Tomb of Northern Zhou Dynasty. Herit. Sci. 11, 224 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Natural reinforcing effect of inorganic colloids on excavated ancient jades. J. Cult. Herit. 46, 52–60 (2020).

Gheno, G., Badetti, E., Brunelli, A., Ganzerla, R. & Marcomini, A. Consolidation of Vicenza, Arenaria and Istria stones: a comparison between nano-based products and acrylate derivatives. J. Cult. Herit. 32, 44–52 (2018).

Gemelli, G. M. C., Zarzuela, R., Alarcón-Castellano, F., Mosquera, M. J. & Gil, M. L. A. Alkoxysilane-based consolidation treatments: laboratory and 3-years in-situ assessment tests on biocalcarenite stone from Roman Theatre (Cádiz). Constr. Build. Mater. 312, 125398 (2021).

Franzoni, E., Graziani, G. & Sassoni, E. TEOS-based treatments for stone consolidation: acceleration of hydrolysis–condensation reactions by poulticing. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 74, 398–405 (2015).

Rodrigues, A., Sena Da Fonseca, B., Ferreira Pinto, A. P., Piçarra, S. & Montemor, M. F. Synthesis and application of hydroxyapatite nanorods for improving properties of stone consolidants. Ceram. Int. 48, 14606–14617 (2022).

Rodrigues, A., da Fonseca, B. S., Pinto, A. P. F., Piçarra, S. & Montemor, M. F. Exploring alkaline routes for production of TEOS-based consolidants for carbonate stones using amine catalysts. New J. Chem. 45, 3833–3847 (2021).

Da Sena Fonseca, B. et al. Effect of the pore network and mineralogy of stones on the behavior of alkoxysilane-based consolidants. Constr. Build. Mater. 345, 128383 (2022).

Xu, F., Zeng, W. & Li, D. Recent advance in alkoxysilane-based consolidants for stone. Prog. Org. Coat. 127, 45–54 (2019).

Sena Da Fonseca, B., Ferreira Pinto, A. P., Piçarra, S. & Montemor, M. F. Alkoxysilane-based sols for consolidation of carbonate stones: proposal of methodology to support the design and development of new consolidants. J. Cult. Herit. 43, 51–63 (2020).

Salazar-Hernández, C., Salazar-Hernández, M. & Mendoza-Miranda, J. M. The sol–gel process applied in the stone conservation. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 106, 495–517 (2023).

Burgos-Cara, A., Rodríguez-Navarro, C., Ortega-Huertas, M. & Ruiz-Agudo, E. Bioinspired alkoxysilane conservation treatments for building materials based on amorphous calcium carbonate and oxalate nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 4954–4967 (2019).

He, J. et al. Ethyl silicate–nanolime treatment for the consolidation of calcareous building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 418, 135437 (2024).

Barberena-Fernandez, A. M., Blanco-Varela, M. T. & Carmona-Quiroga, P. M. Use of nanosilica- or nanolime-additioned TEOS to consolidate cementitious materials in heritage structures: physical and mechanical properties of mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 95, 271–276 (2019).

Zárraga, R., Cervantes, J., Salazar-Hernandez, C. & Wheeler, G. Effect of the addition of hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane to TEOS-based stone consolidants. J. Cult. Herit. 11, 138–144 (2010).

Liu, R., Han, X., Huang, X., Li, W. & Luo, H. Preparation of three-component TEOS-based composites for stone conservation by sol–gel process. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 68, 19–30 (2013).

Illescas, J. F. & Mosquera, M. J. Producing surfactant-synthesized nanomaterials in situ on a building substrate, without volatile organic compounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 4259–4269 (2012).

Zhao, G. et al. Breathable hyperbranched polysiloxane for the conservation of silicate cultural heritages. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 106, 518–529 (2023).

Peng, X. et al. Sol–gel derived hybrid materials for conservation of fossils. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 94, 347–355 (2020).

da Fonseca, B. S., Piçarra, S., Pinto, A. P. F. & de Montemor, M. F. Polyethylene glycol oligomers as siloxane modificators in consolidation of carbonate stones. Pure Appl. Chem. 88, 1117–1128 (2016).

Gemelli, G. M. C., Zarzuela, R., Fernandez, F. & Mosquera, M. J. Compatibility, effectiveness and susceptibility to degradation of alkoxysilane-based consolidation treatments on a carbonate stone. J. Build. Eng. 42, 102840 (2021).

Facio, D. S., Luna, M. & Mosquera, M. J. Facile preparation of mesoporous silica monoliths by an inverse micelle mechanism. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 247, 166–176 (2017).

Gherardi, F. & Maravelaki, P. N. Advances in the application of nanomaterials for natural stone conservation. RILEM Tech. Lett. 7, 20–29 (2022).

Jia, M., Liang, J., He, L., Zhao, X. & Simon, S. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic SiO2-based hybrids in the protection of sandstone for anti-salt damage. J. Cult. Herit. 40, 80–91 (2019).

Li, Z., Wang, R., Bu, F. & Huang, J. Hybrid siloxane oligomer: a promising consolidant for the conservation of powdered tremolite jade artifacts. J. Cult. Herit. 70, 388–396 (2024).

Chen, T.-H., Calligaro, T., Pagès-Camagna, S. & Menu, M. Investigation of Chinese archaic jade by PIXE and μRaman spectrometry. Appl. Phys. A 79, 177–180 (2004).

Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, T., Zari, M. & Liu, Y. Vibrational spectra of Hetian nephrite from Xinjiang. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 32, 398–401 (2012).

Molina, M. T., Cano, E. & Ramírez-Barat, B. Protective coatings for metallic heritage conservation: a review. J. Cult. Herit. 62, 99–113 (2023).

Broda, M., Mazela, B. & Dutkiewicz, A. Organosilicon compounds with various active groups as consolidants for the preservation of waterlogged archaeological wood. J. Cult. Herit. 35, 123–128 (2019).

Plaza, N. Z., Pingali, S. V. & Broda, M. The effect of organosilicon compounds on the nanostructure of waterlogged archeological oak studied by neutron and X-ray scattering. J. Cult. Herit. 71, 203–210 (2025).

Masi, G. et al. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy as a tool to investigate silane-based coatings for the protection of outdoor bronze: the role of alloying elements. Appl. Surf. Sci. 433, 468–479 (2018).

Ashkenazi, D. et al. A method of conserving ancient iron artefacts retrieved from shipwrecks using a combination of silane self-assembled monolayers and wax coating. Corros. Sci. 123, 88–102 (2017).

Wang, D. & Bierwagen, G. P. Sol–gel coatings on metals for corrosion protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 64, 327–338 (2009).

Balbo, A., Chiavari, C., Martini, C. & Monticelli, C. Effectiveness of corrosion inhibitor films for the conservation of bronzes and gilded bronzes. Corros. Sci. 59, 204–212 (2012).

Chiavari, C. et al. Protective silane treatment for patinated bronze exposed to simulated natural environments. Mater. Chem. Phys. 141, 502–511 (2013).

Yihang, Z., Xueqi, C., Kai, W. & Dongbo, H. U. Study on the mechanism of dimensional stabilization of waterlogged archaeological wood treated by γ-mercaptopropyltriethoxysilane. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 33, 1–11 (2021).

Mohamed, H. M., Ahmed, N. M., Mohamed, W. S. & Mohamed, M. G. Advanced coatings for consolidation of pottery artifacts against deterioration. J. Cult. Herit. 64, 63–72 (2023).

Navarro-Moreno, D. et al. Nanolime, ethyl silicate and sodium silicate: advantages and inconveniences in consolidating ancient bricks (XII-XIII century). Constr. Build. Mater. 277, 122240 (2021).

Zhu, J. et al. In-situ growth synthesis of nanolime/kaolin nanocomposite for strongly consolidating highly porous dinosaur fossil. Constr. Build. Mater. 300, 124312 (2021).

Liu, Z., Zhu, L. & Zhang, B. In-situ formation of an aluminum phosphate coating with high calcite-lattice matching for the surface consolidation of limestone relics. Constr. Build. Mater. 392, 131836 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Co-depositing bio-inspired tannic acid-aminopropyltriethoxysilane coating onto carbon fiber for excellent interfacial adhesion of epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 204, 108639 (2021).

Scott, A. F., Gray-Munro, J. E. & Shepherd, J. L. Influence of coating bath chemistry on the deposition of 3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane films deposited on magnesium alloy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 343, 474–483 (2010).

Barberena-Fernández, A. M., Carmona-Quiroga, P. M. & Blanco-Varela, M. T. Interaction of TEOS with cementitious materials: chemical and physical effects. Cem. Concr. Compos. 55, 145–152 (2015).

Hayami, R. et al. Preparation and characterization of stable DQ silicone polymer sols. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 88, 660–670 (2018).

Sato, Y., Hayami, R. & Gunji, T. Characterization of NMR, IR, and Raman spectra for siloxanes and silsesquioxanes: a mini review. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 104, 36–52 (2022).

Fonseca, B. S., da Piçarra, S., Pinto, A. P. F., Ferreira, M. J. & Montemor, M. F. TEOS-based consolidants for carbonate stones: the role of N1-(3-trimethoxysilylpropyl)diethylenetriamine. New J. Chem. 41, 2458–2467 (2017).

Yamamoto, K. et al. Preparation and film properties of polysiloxanes consisting of di- and quadra-functional hybrid units. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 104, 724–734 (2022).

Capasso, I., Colella, A. & Iucolano, F. Silica-based consolidants: enhancement of chemical-physical properties of Vicenza stone in heritage buildings. J. Build. Eng. 68, 106124 (2023).

Aldosari, M. A., Darwish, S. S., Adam, M. A., Elmarzugi, N. A. & Ahmed, S. M. Evaluation of preventive performance of kaolin and calcium hydroxide nanocomposites in strengthening the outdoor carved limestone. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 11, 3389–3405 (2019).

Vuori, L. et al. Controlling the synergetic effects in (3-aminopropyl) trimethoxysilane and (3-mercaptopropyl) trimethoxysilane coadsorption on stainless steel surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 317, 856–866 (2014).

Han, Z., Huang, X., Chen, J. & Chen, J. 2-Mercaptobenzimidazole compounded with the conventional sealer B72 for the protection of rusted bronze. J. Cult. Herit. 67, 42–52 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Raman spectroscopy and XPS study of the thermal decomposition of Mg-hornblende into augite. J. Raman Spectrosc. 53, 820–831 (2022).

Rupasinghe, B. & Furgal, J. C. Degradation of silicone-based materials as a driving force for recyclability. Polym. Int. 71, 521–531 (2022).

Li, J. Research status and development trend of ceramifiable silicone rubber composites: a brief review. Mater. Res. Express 9, 012001 (2022).

Lou, W., Xie, C. & Guan, X. Molecular dynamic study of radiation-moisture aging effects on the interface properties of nano-silica/silicone rubber composites. Npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 1–13 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Research Center for Cultural Heritage Conservation at Fudan University and the Key Laboratory of Silicate Cultural Relics Conservation at Shanghai University. This study was supported by the Science and Technology Major Special Program Project of Shanxi Province (grant number 202201150501024) and the Project of Key Laboratory of Silicate Cultural Relics Conservation (Shanghai University), Ministry of Education [grant numbers SCRC2023KF03TS, SCRC2023ZZ03ZD].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Experimentation, Data collection, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. J. Hu: Experimentation, Writing—review and editing. R.W.: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing—review and editing. F.B.: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing—review and editing. J. Huang: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Hu, J., Wang, R. et al. Mercapto-functionalized siloxane for enhanced conservation of tremolite jade artifacts. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01752-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01752-5