Abstract

During the Neolithic period, distinct agricultural patterns emerged in China, with millet farming dominating the north and rice farming the south, shaped by geographic and climatic differences. The Fenghuangzui earthen-walled town, located in the middle Hanshui River region—a transitional zone between northern and southern China, was occupied from the Qujialing (5300–4500 cal BP) to Meishan (4200–3900 cal BP) periods, reflecting cultural influences from both regions. This study analyzed plant macro-remains from Fenghuangzui, revealing intensive rice farming alongside micro-scale millet cultivation throughout these periods. This contrasts with the millet-dominated western middle Hanshui River region and the northern region’s mixed system with a stronger emphasis on rice. The findings shed light on the agricultural foundation of Neolithic wall towns in the middle Hanshui River region and promote understanding of cultural interactions and farming practices in this transitional zone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Millet and rice were domesticated approximately 10,000 years ago in northern and southern China, respectively1,2,3,4. Following their domestication, millet and rice agriculture dispersed to the south and north, likely facilitated by population migration, cultural interactions, and environmental adaptation5,6,7. The north-south transitional zone of China8, characterized by high environmental complexity, biodiversity, and a transitional climate9, played a crucial role in facilitating the movement of people and the exchange of agricultural technologies. Archaeobotanical evidence indicates a mixed agricultural system combining millet and rice cultivation developed in this transitional zone6,10,11,12,13. Three primary crop dispersal routes have been proposed for Neolithic China: the west corridor (Gansu-Qinghai to Chengdu Plain), the central corridor (Central Plains and Hanshui River region), and the east corridor (Haidai to Jiangsu-Zhejiang regions)6. Among these, the central corridor, particularly the middle Hanshui River region, is notable for its early and frequent crop exchanges in prehistoric and historic times. (By ‘middle Hanshui River region,’ we refer to the middle reach of the Hanshui River, the largest tributary of the Yangtze River).

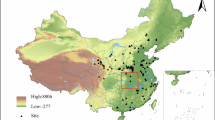

Several sites in the middle Hanshui River region, including Baligang, Gouwan, Shenmingpu, Wenkandong, Wuying, Dasi, Xiawanggang, Qinglongquan, Jijiawan, Mulintou, and Xiajiangjiabianzi, have been excavated and studied for their plant macro-remains (see Fig. 1 for geographic locations of the above sites and Supplementary Tables 1–4 in Supplementary Information for their plant macro-remains results). These studies reveal that millet-rice mixed agriculture was established at Baligang around 8400 years ago and persisted in subsequent periods14. The western mountainous areas are predominantly millet-based, while the eastern plains are dominated by rice farming15.

The recent discovery of a Late Neolithic earthen-walled town at Fenghuangzui in Xiangyang City, Hubei Province, provides new insights into the agricultural patterns of the middle Hanshui River region. Influenced by the Qujialing and Shijiahe cultures from the Jianghan Plain, Fenghuangzui shows less influence from the Central Plains despite its geographic proximity to the Central Plains16. To understand the subsistence strategies of Fenghuangzui’s inhabitants and their differences from those in the western or northern Hanshui River region, we conducted an archaeobotanical study of plant macro-remains from the site. Our findings reveal the agricultural foundation of the Fenghuangzui walled town and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of agricultural structures in the middle Hanshui River region during the Qujialing to Meishan periods.

Methods

The middle Hanshui River region, a transitional zone between North and South China, encompasses three geomorphological areas: western mountains, northern basins, and southern plains (see Fig. 1b). It serves as a cultural meeting point between the Central Plains and the Jianghan Plain, with shifting cultural influence over time. Key cultures in the region include the Yangshao (7000—5000 cal BP), Qujialing (5300–4500 cal BP), Shijiahe (4500–4200 cal BP), and Meishan (4200–3900 cal BP) cultures17.

The Yangshao culture, originating in the Yellow River Basin, is known for its painted pottery18 and dry farming of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum). The Qujialing culture, centered in the Jianghan Plain of the middle Yangtze River region, featured large settlements with fine-paste black and gray pottery, including bei-cups, wan-bowls, hu-jars, and dou-stemmed bowls19. The surfaces of the pottery are predominantly plain, though a small portion features decorations such as string patterns, basket patterns, incised patterns, and appliqué patterns20. The Shijiahe culture, originating in the Jianghan Plain, is marked by gray and black pottery, ritual animal figurines, advanced jade production, and evidence of social stratification19,21. The Meishan culture, emerging in the Central Plains of the Yellow River, produced high-fired, thin-walled black and gray pottery, including guan-jars, ding-tripods, and pan-basins22.

The Fenghuangzui site (32°14′42.67″ N, 111°59′20.39″ E) (Fig. 1b), a 15-ha Neolithic walled settlement in Xiangyang City, Hubei Province, was occupied during the Qujialing, Shijiahe, and Meishan periods (see Table 1). Excavation since 2020 reveals a nearly square-shaped town with moats and river courses23,24. Pottery styles are strongly influenced by the Jianghan Plains, despite its proximity to the Central Plains16. Paleoenvironmental studies25 indicate a warm, humid climate during the Qujialing period, supporting cultural expansion. Cooling and drying during the Shijiahe period led to the site’s decline from a regional center to an ordinary settlement. By the Meishan period, the strong influence of the Central Plains was evident at the site, probably leading to the site’s abandonment. These broader paleoenvironmental conditions align closely with the rise and decline of the town, as evidenced by the archeological record.

Flotation and identification of plant macro-remains

The present study aims to understand the agricultural foundation of the Fenghuangzui walled town during the Neolithic times and its potential changes over time, from the perspective of plant macro-remains. Archaeological plant remains are broadly categorized into macro-remains (visible to the naked eye, e.g., seeds, wood) and micro-remains (requiring microscopy, e.g., pollen, phytoliths, starch grains)26. Flotation, a well-established method for recovering plant macro-remains26,27, has been widely applied in Chinese archeology since the 2000s28. We employed the flotation method for plant macro-remains recovery. Adopting a sampling strategy developed by Zhijun Zhao, a prominent Chinese archaeobotanist29, we collected 418 soil samples (~10 L each, totaling 4916 L) from various features and contexts dating to the Qujialing to Meishan periods, including ash pits, house structures, ash ditches, stratigraphic units, and so on (see archeological contexts of the selected soil samples in Table 2). A simple bucket flotation method was used, with light fractions collected on a 0.2 mm mesh. Soil samples were manually agitated and soaked to enhance recovery. Shade-dried samples were analyzed at Wuhan University’s Archeology Department, where charred remains (charcoal, seeds, and fruits) were identified using published references and examined under an Olympus SZX7 microscope. Uncharred materials were excluded as modern intrusions. Data were analyzed using absolute counts, density, proportions, and ubiquity to assess seed/grain abundance and distribution. Spatial patterns were visualized using ESRI’s ArcMap 10.1, identifying hotspots and coldspots of seed/grain distribution and potential intra-community differences in food consumption within the community. This approach provides insights into the agricultural and subsistence strategies of Fenghuangzui’s Neolithic inhabitants over time.

Results

Charcoals are black, carbon-rich material produced by heating plant materials in an environment with limited oxygen. This incomplete combustion removes water, volatile compounds, and other organic components, leaving behind a lightweight, porous, and carbon-dense residue. Charcoal remains, derived from human use of wood for fuel and raw materials, serve as valuable archaeobotanical evidence for reconstructing long-term anthropogenic landscapes30. In this study, only charcoal fragments larger than 1 mm were weighted, totaling 152.78 g, with an average content of 0.03 g/L. A total of 2942 charred plant seeds were recovered, of which 2782 were identified to the species level. The remaining 160 seeds, severely damaged or lacking diagnostic features, were classified as ‘unknown’ (Table 3). The identified seeds represent 28 species across 14 families, categorized into two groups: crop seeds and non-crop seeds. This dataset provides insights into agricultural practices and the broader use of plant resources.

Four major crops

Four crops were identified from the charred grains: rice (Oryza sativa), foxtail millet (S. italica), broomcorn millet (P. miliaceum), and wheat (Triticum aestivum) (Fig. 2). These totaled 2526 grains, representing 90.83% of the identifiable charred plant seeds.

(1) Rice (O. sativa): a total of 2504 charred rice grains were recovered, accounting for 99.13% of the crop grains, with a ubiquity of 62.9%. The grains were well-preserved, exhibiting an elongated ellipsoid shape with two surface notches (Fig. 2a). Measurements of 20 grains yielded average dimensions of 4.8 mm (length), 2.46 mm (width), and 1.99 mm (thickness), with a length-to-width (L/W) ratio of 1.95. We infer that the rice found at Fenghuangzui belongs to the japonica subspecies (O. sativa ssp. japonica), as this subspecies typically has an L/M ratio of less than 2.231.

(2) Foxtail millet (S. italica): fourteen charred foxtail millet grains were identified, representing 0.55% of the crop grains, with a ubiquity of 3.1%. The grains are subglobose, with a bulging globular abdomen and a “U”-shaped embryonic region (Fig. 2b). Size variations suggest mature (A-type) and immature (C-type) grains, with mature grains exclusively found in the Shijiahe cultural contexts32.

(3) Broomcorn millet (P. miliaceum): three charred broomcorn millet grains were recovered, accounting for 0.12% of the crop grains, with a ubiquity of 0.72%. The grains are subglobose, with a rough surface and a “V”-shaped embryonic region (Fig. 2c). Two well-preserved grains averaged 1.67 mm (length) and 1.57 mm (width).

(4) Wheat (T. aestivum): five charred wheat grains were identified, representing 0.2% of the crop grains, with a ubiquity of 0.96%. The grains are ovate-ellipsoid, with a raised dorsal surface and pronounced ventral grooves (Fig. 2d). Two grains averaged 3.08 mm (length), 1.91 mm (width), and 1.54 mm (thickness). One grain was collected from the Qujialing (5300–4500 cal BP) context, and the other four from the Shijiahe (4500–4200 cal BP) context. These findings are among the earliest wheat remains in the middle Hanshui River region33, though accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C dating is needed to confirm this inference.

Next, we described crop remains by cultural periods (Qujialing, Shijiahe, and Meishan) (Fig. 3). In the Qujialing period, of 684 identifiable charred seeds, 618 (90.35%) were crop grains, including 612 (99.03%, ubiquity 69.92%) rice gains, four foxtail millet grains (0.65%, ubiquity 3.01%), one broomcorn millet grain (0.16%, ubiquity 0.75%), and one wheat grain (0.16%, ubiquity 0.75%) (Fig. 3). Rice dominated the diet, while millets and wheat were negligible. In the Shijiahe period, of 2032 identifiable charred seeds, 1856 (91.34%) were crop grains, including 1840 rice grains (99.14%, ubiquity 56.91%), ten foxtail millet grains (0.54%, ubiquity 3.66%), two broomcorn millet grains (0.11%, ubiquity 0.81%), and four wheat grains (0.22%, ubiquity 1.22%) (Fig. 3). Rice remained predominant, with minimal contributions from millets and wheat. In the Meishan period, all 52 grains recovered were rice, accounting for 78.79% of the charred seeds, with a ubiquity of 48.72% (Fig. 3). No millets or wheat were found, indicating rice was the sole cultivated crop during this period.

From the Qujialing to Meishan periods, rice was the dominant crop at Fenghuangzui, becoming the sole cultivated crop by the Meishan period. Foxtail millet, broomcorn millet, and wheat were present in small quantities during the Qujialing and Shijiahe periods, suggesting minimal dry farming. These findings highlight the centrality of rice farming in supporting Late Neolithic town life at Fenghuangzui, with dry farming playing a minor role.

The number of charred seeds varies significantly across periods (Table 3), primarily due to differences in the volume of soil samples collected, which reflects the abundance of cultural deposits in each period. To reduce the sampling bias, we standardized the data and used percentages and ubiquity in the discussion section.

Non-crop seeds

A total of 256 seeds, representing 14 families, were recovered through flotation analysis, accounting for 9.37% of the identifiable plant seeds (Fig. 4). The most abundant were Chenopodiaceae (75 seeds, 29.3% of non-crop seeds), followed by Portulaca oleracea (47 seeds, 18.36% of non-crop seeds) and Acalypha australis (25 seeds, 9.77% of non-crop seeds). These findings highlight the diversity of wild plant resources utilized at the site.

Discussion

The middle Hanshui River region, home to the Fenghuangzui site, is a crucial zone for crop exchange and population movement between North and South China. By analyzing crop structures at Fenghuangzui and integrating data from other sites in the region (see Fig. 5), we observe significant spatio-temporal changes influenced by geography, cultural evolution, and climate variability.

Yangshao period (7000–5000 cal BP)

No plant remains were recovered from Fenghuangzui during this period. However, studies at four other sites— Baligang (northern basins) and Gouwan, Dasi, and Xiawanggang (western mountains)—revealed a mixed agricultural system of millet and rice (Fig. 5a, b). Rice dominated in the northern basins, while millet farming prevailed in the western mountains, reflecting geomorphological influences: flat northern basins facilitated rice irrigation, whereas mountainous terrain favored drought-tolerant millet.

Qujialing period (5300–4500 cal BP)

Plant macro-remains from seven sites, including Fenghuangzui, Baligang, and Qinglongquan, indicate a continuation of mixed dry-rice agriculture, with a significant increase in rice cultivation (Fig. 5c, d). The Qujialing culture, originating in the Jianghan Plain, expanded northward, establishing rice farming as its agricultural foundation. Fenghuangzui, located in the southern Xiangyang-Yicheng Plain, exhibited the most intensive rice cultivation, closely resembling the Jianghan Plain’s agricultural structure34. Cultural connections are further supported by similarities in pottery types between Fenghuangzui and Zoumaling sites in the Jianghan Plain16,35.

Shijiahe period (4500–4200 cal BP)

Analysis of plant macro-remains from Qinglongquan, Gouwan, Xiawanggang, Baligang, and Fenghuangzui, shows the persistence of mixed dry-rice agriculture (Fig. 5e, f), with advancements in dry farming. Wheat appeared at some sites but remained insignificant. Agricultural patterns established during the Qujialing period continued, with rice cultivation thriving in the southern plains and mixed farming in the western mountains and northern basins.

Meishan period (4200–3900 cal BP)

Data from seven sites, including Fenghuangzui, Wenkandong, and Baligang, reveal a shift toward dry agriculture, with reduced rice cultivation (Fig. 5g, h). Wheat appeared sporadically but played a minor role. Dry farming dominated the western mountains, while rice agriculture declined in the northern basins. However, Fenghuangzui maintained its rice-based agricultural system, even though dry farming became evident in the region.

The decline of Jianghan Plain cultures and the southward expansion of the Meishan culture, coupled with a climatic shift toward cooler and drier conditions36,37,38, promoted dry agriculture in the middle Hanshui River region. Unfavorable water and heat conditions, combined with mountainous terrain, made rice cultivation increasingly untenable in the western mountains, solidifying dry agriculture as the dominant agricultural practice.

Archaeobotanical macro-remains, as anthropogenic deposits, provide insights into past human activities, linking behaviors to specific spaces and times. The spatial distribution and density of these remains help identify areas for crop processing, food preparation, and communal consumption, offering a window into agricultural production and redistribution39,40,41,42,43. Ash pits, often repositories for domestic waste, typically contain higher concentrations of charred plant remains, reflecting daily lives. Of the 418 soil samples analyzed, 250 (59.8%) were from ash pits, widely distributed across the 2020 excavation area. By mapping crop grain densities, we identified hotspots (high density) and coldspots (low density), revealing spatial activity patterns within the community. Using each test unit as an analytical unit, we quantified charred crop grains, calculated their densities, and created bubble maps (see Figs. 6–8), where larger bubbles indicate higher grain densities).

In the Qujialing period (5300–4500 cal BP), crop grains were concentrated in the southwest and southern corners of the excavation area (Fig. 6), likely representing primary residential and activity zones. During the Shijiahe period, crop grains were distributed more widely across the site (Fig. 7), suggesting increased residential or activity levels. The southwest corner remained a hotspot, consistent with the Qujialing period, while the eastern area showed fewer remains, indicating less frequent habitation. In the Meishan period, evidence of activity diminished, with traces primarily in the northeastern part of the site (Fig. 8). This shift may reflect changing residential patterns or the site’s decline, but further investigation is required to confirm this inference. Overall, the distribution of crop grains expanded from the southwest and south towards the east and northeast over time. During the Shijiahe period, grains were widely distributed, while in the Meishan period, they were restricted to the northeast. Assuming that more ash pits indicate more significant domestic activity, the charred crop grains reflect the daily lives of Fenghuangzui’s inhabitants. These patterns suggest that Neolithic town life at Fenghuangzui emerged during the Qujialing period, peaked in the Shijiahe period, and declined in the Meishan period.

The archaeobotanical record at a site is influenced by complex pre- and post-depositional processes44. Post-depositional processes, such as water runoff, wind transportation, and topography, can displace plant remains, limiting interpretive accuracy. For instance, the presence of wheat at the Fenghuangzui site is cautiously interpreted as it may result from stratigraphic disturbance. Further radiocarbon dates may shed more light on this issue.

The Fenghuangzui site and surrounding areas were intensively used as rice fields before the 2020 excavation, indicating that the modern environmental conditions support rice farming. Plant macro-remains suggest that Late Neolithic inhabitants cultivated local rice. However, the complete absence of archeological rice spikelet bases in the excavation area implies that rice was pre-processed elsewhere before being transported to the excavation area for consumption.

In archaeobotanical studies, rice spikelet bases are key markers for distinguishing wild from domesticated rice45. Spikelets are typically removed during threshing, a post-harvest process that converts rice stalks into edible grains46. Thus, the presence of spikelet bases indicates on-site threshing, while their absence suggests off-site processing. At Fenghuangzui, all recovered rice remains were grains (n = 2504), with no husks or spikelet bases identified. This pattern, observed across 418 soil samples, is unlikely due to sampling bias. Additionally, just one charred seed of Echinochloa crus-galli, a common rice paddy weed often found at prehistoric sites14,47,48, was recovered. These findings support the hypothesis that rice was threshed and pre-processed elsewhere before being transported to the excavation area.

The scatter plot in Fig. 9 shows no positive correlation between charred crop grains and non-crop seeds recovered through flotation. Excavation units with non-crop seeds show slight variation in quantity, while those with crop grains show significant differences. Given that crop seeds, such as rice, were likely pre-processed elsewhere, non-crop plants were neither related to agricultural production nor transported with crops during harvesting.

We propose that Neolithic inhabitants intentionally utilize non-crop plants. Identified species include Chenopodiaceae (n = 75), P. oleracea (n = 47), Perilla frutescens (n = 7), and wild soybeans (Glycine soja), which may have been consumed as wild vegetables or fodder. These three species collectively account for 50.39% of non-crop seeds, suggesting that wild plants supplemented the human or domestic animal’s diet. Additionally, four fruit kernel fragments (Fig. 4) from the Shijiahe period indicate fruit consumption. Similar patterns are observed at other middle Hanshui River sites, such as Qinglongquan, Gouwan, and Dasi, where Chenopodiaceae, P. oleracea, and P. frutescens were also recovered33,49,50. Western mountainous areas utilized local fruit resources (e.g., Actinidia, Vitis, and Diospyros)51, while the Jianghan Plain relied on fruits (Ziziphus, Diospyros, Vitis, Rubus, Actinidia, and Amygdalus) and aquatic plants (Trapa sp. and Euryale ferox)34. These findings highlight regional differences in wild plant resource utilization.

Analysis of plant macro-remains from Fenghuangzui reveals a stable crop assemblage dominated by rice from the Qujialing to Meishan periods, with limited dry crops (foxtail millet and broomcorn millet) and supplementary wild vegetable collection. The absence of crop processing waste (e.g., spikelet bases and rice weeds) suggests that threshing occurred outside the excavation area. The spatial distribution of charred plant remains in ash pits reflects evolving residential patterns, from the emergence of Qujialing culture to the prosperity of Shijiahe culture and the decline of Meishan culture.

In the Neolithic era, agricultural practices in the middle Hanshui River region exhibited significant regional variation. In western mountainous areas, dry farming (primarily foxtail millet) dominated, with limited rice cultivation, influenced by Central Plains and Jianghan cultures, geography, and climate. In northern basins, rice farming prevailed initially, but the southward expansion of Central Plains culture and arid conditions led to a balance between dry and rice agriculture. In the southern plains, where Fenghuangzui is located, rice dominated in both quantity and ubiquity, with minimal foxtail and broomcorn millet, representing a unique agricultural pattern in the region. Our study highlights the centrality of rice farming at Fenghuangzui, supplemented by limited dry crops and wild plant resources, and underscores the influence of cultural, geographical, and climatic factors on regional agricultural practices.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Zuo, X. et al. Dating rice remains through phytolith carbon-14 study reveals domestication at the beginning of the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6486–6491 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Rice’s trajectory from wild to domesticated in East Asia. Science 384, 901–906 (2024).

Lu, H. et al. Earliest domestication of common millet (P. miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10000 years ago. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7367–7372 (2009).

Yang, X. et al. Early millet use in northern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3726–3730 (2012).

Liu, L., Chen, J., Wang, J., Zhao, Y. & Chen, X. Archaeological evidence for initial migration of Neolithic Proto Sino-Tibetan speakers from Yellow River valley to Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2212006119 (2022).

He, K., Lu, H., Zhang, J., Wang, C. & Huan, X. Prehistoric evolution of the dualistic structure mixed rice and millet farming in China. Holocene 27, 1885–1898 (2017).

Guedes, Jd’Alpoim, Jin, G. & Bocinsky, R. K. The impact of climate on the spread of rice to north-eastern China: a new look at the data from Shandong Province. PLoS One 10, e0130430 (2015).

Kou, Z., Yao, Y., Hu, Y. & Zhang, B. Discussion on position of China’s north-south transitional zone by comparative analysis of mountain altitudinal belts. J. Mt. Sci. 17, 1901–1915 (2020).

Li, Y., Wang, X., Xing, G. & Wang, D. Meteorological disaster disturbances on the main crops in the north-south transitional zone of China. Sci. Rep. 14, 8846 (2024).

Huan, X. et al. Discovery of the earliest rice paddy in the mixed rice–millet farming area of China. Land 11, 831 (2022).

Huan, X., Deng, Z., Xiang, J. & Lu, H. New evidence supports the continuous development of rice cultivation and early formation of mixed farming in the middle Han River valley, China. Holocene 32, 924–934 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Mixed farming of rice and millets became the primary subsistence strategy 6400 years ago in the western Huanghuai Plain of Central China: new macrofossil evidence from Shigu. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 15, 122 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. The emergence, development and regional differences of mixed farming of rice and millet in the upper and middle Huai River valley, China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 1779–1790 (2016).

Deng, Z. et al. From early domesticated rice of the middle Yangtze Basin to millet, rice, and wheat agriculture: archaeobotanical macro-remains from Baligang, Nanyang Basin, central China (6700–500 BC). PLoS One 10, e0139885 (2015).

Guo, L. & Zhang, B. Research on crop structure in Han River valley in prehistoric period. Agric. Archaeol. 4, 13–21 (2022).

Ao, X., Wu, J., Xie, Z. & Li, T. Chemical insights into pottery production and use at Neolithic Fenghuangzui earthen-walled town in China. npj Herit Sci. 13, 156 (2025).

He, Q. Research on Neolithic Cultures at the Middle Reaches of the Han River and the Interaction with its Neighborhoods’ Cultures. Ph.D. Dissertation (Jilin University, Changchun, 2015).

An, T., Văleanu, M.-C., Huan, R., Yanxiang, F. & Luoya, Z. The Yangshao culture in China. A short review of over 100 years of archaeological research (I). Cercet. Istor. Ser. Noua 42, 53–85 (2022).

Zhang, C. The Qujialing-Shijiahe culture in the middle Yangzi River valley. In A Companion to Chinese Archaeology (ed. A. P., Underhill) 510–534 (Wiley-Blackwell Press, Malden, 2013).

Shan, S. A Study on the Qujialing Culture (Ph.D. Dissertation, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 2018).

Li, T., Underhill, A. P. & Shan, S. Shijiahe and its implications for understanding the development of urbanism in Late Neolithic China. J. Urban Archaeol. 7, 31–49 (2023).

Yuan, F. Research of the Meishan Culture. Ph.D. Dissertation (Wuhan University, Wuhan, 2020).

Li, T. et al. Surface treatment of red painted and slipped wares in the middle Yangtze River valley of Late Neolithic China: multi-analytical case analysis. Herit. Sci. 10, 188 (2022).

Li, G. Y. et al. Raw materials and technological choices: case study of Neolithic black pottery from the middle Yangtze River valley of China. Open Archaeol. 11, 20240025 (2025).

Guo, A., Mao, L., Li, C. & Mo, D. Reconstruction of the paleoenvironmental context of Holocene human behavior at the Fenghuangzui site in the Nanyang Basin, Middle Yangtze River, China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 2 (2025).

Nesbitt, M. Plants and people in Ancient Anatolia. Biblic. Archaeol. 58, 68–81 (1995).

Fuller, D., Korisettar, R., Venkatasubbaiah, P. C. & Jones, M. K. Early plant domestications in southern India: some preliminary archaeobotanical results. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 13, 115–129 (2004).

Zhao, Z. New data and new issues for the study of origin of rice agriculture in China. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2, 99–105 (2010).

Zhao, Z. Floatation: a paleobotanic method in field archaeology. Archaeology 3, 80–87 (2004).

Kabukcu, C. Wood charcoal analysis in archaeology. In Environmental Archaeology: Current Theoretical and Methodological Approaches (eds. Pişkin, E., Marciniak, A. & Bartkowiak, M.) 133–154 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Castillo, C. C. et al. Archaeogenetic study of prehistoric rice remains from Thailand and India: evidence of early japonica in South and Southeast Asia. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 8, 523–543 (2016).

Song, J., Zhao, Z. & Fuller, D. Q. The archaeobotanical significance of immature millet grains: an experimental case study of Chinese millet crop processing. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 22, 141–152 (2013).

Ng, C. Y. Analysis of plant remains from Qinglongquan site in Yun County, Hubei Province. Master thesis (Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Social Science, Beijing, 2011).

Yao, L., Tao, Y., Zhang, D., Luo, Y. & Cheng, Z. Analysis of charred plant remains from the Qujialing site in Jingmen, Hubei Province. Jianghan Archaeol 6, 116–124 (2019).

Wu, J., Ao, X., Liu, F., Wang, X. & Li, T. Chemical insights into pottery production and use at Neolithic Zoumaling earthen-walled town in China. npj Herit Sci. 13, 115 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Palaeoecological records of environmental change and cultural development from the Liangzhu and Qujialing archaeological sites in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Quat. Int. 227, 29–37 (2010).

Jiang, Q. & Piperno, D. R. Environmental and archaeological implications of a Late Quaternary palynological sequence, Poyang Lake, southern China. Quat. Res. 52, 250–258 (1999).

Li, B. et al. Linking the vicissitude of Neolithic cities with mid Holocene environment and climate changes in the middle Yangtze River, China. Quat. Int. 321, 22–28 (2014).

Hald, M. M. Distribution of crops at late Early Bronze Age Titriş Höyük, southeast Anatolia: towards a model for the identification of consumers of centrally organised food distribution. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 19, 69–77 (2010).

Hald, M. M. & Charles, M. Storage of crops during the fourth and third millennia B.C. at the settlement mound of Tell Brak, northeast Syria. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 17, 35–41 (2008).

Bogaard, A. et al. Private pantries and celebrated surplus: storing and sharing food at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Central Anatolia. Antiquity 83, 649–668 (2009).

Alonso, N., Junyent, E., Lafuente, A. & López, J. B. Plant remains, storage and crop processing inside the Iron Age fort of Els Vilars d’Arbeca (Catalonia, Spain). Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 17, 149–158 (2008).

Calo, C. M. Archaeobotanical remains found in a house at the archaeological site of Cardonal, Valle del Cajón, Argentina: a view of food practices 1800 years ago. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 23, 577–590 (2014).

Pearsall, D. M. Paleoethnobotany: A Handbook of Procedures (Routledge, New York, 2016).

Fuller, D. Q. et al. The domestication process and domestication rate in rice: spikelet bases from the Lower Yangtze. Science 323, 1607–1610 (2009).

Fuller, D. Q. Rice: A User Guide for Archaeologists (University College London, 2018).

Zheng, Y. F. et al. Rice fields and modes of rice cultivation between 5000 and 2500 BC in east China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 2609–2616 (2009).

Dal Martello, R. et al. Early agriculture at the crossroads of China and Southeast Asia: Archaeobotanical evidence and radiocarbon dates from Baiyangcun, Yunnan. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 20, 711–721 (2018).

Wang, Y., Zhang, P., Jin, G. & Jin, S. Results and analyses of the plant flotation at Gouwan Site, Xichuan, Henan, China in the excavation of 2007. Sichuan Relics 2, 80–92 (2011).

Tang, L., Huang, X. & Guo, C. Analysis of plant remains unearthed at the Dasi site in Yunxian County, Hubei Province: analysis of the prehistoric agricultural characteristics of the mountainous areas in northwestern Hubei and southwestern Henan Province. West. Archaeol. 2, 73–85 (2016).

Tang, L., Tian, J., Liu, J., Da, H. & Qu, L. Research on the mode of mountain subsistence in the period of Qujialing culture: an example of Mulintou site in Baokang, Hubei Province. South. Relics 5, 189–199 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Ran Zheng, Mrs. Hongli Yu, Rong Chen, and Dongxue Yu (Department of Archeology, Wuhan University) for helping select seeds from flotation samples. This study received financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (grant agreement number 2022YFF0903605).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. and X.H. conceived the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and were significant contributors to the writing of the manuscript. X.H., T.W., and X.Y. carried out the sampling of soil samples. Y.H. and P.F. participated in flotation analysis and identification of plant macro-remains. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

X.Y., a co-author of this manuscript, serves as a Guest Editor for the article collection “Cultural Heritage of Neolithic Walled Towns in the Middle Yangtze River Valley: from Archeological Discoveries to Scientific Interpretation.” However, he has not been involved in the peer review process or editorial decisions regarding this submission. The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Wu, T., Fan, P. et al. Agricultural foundations of the Late Neolithic walled town at Fenghuangzui in central China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 194 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01772-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01772-1

This article is cited by

-

Animal exploitation of the Fenghuangzui Neolithic walled settlement in the Middle Yangtze River Valley

npj Heritage Science (2025)