Abstract

This study used portable Raman spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence to non-destructively analyze pigments in the architectural decorative patterns of Prince Kung’s Palace, Beijing. Focusing on eight representative patterns, it identified a complex palette of pigments, including historical mineral, modern synthetic, and plant-derived ones. The mineral pigments identified are cinnabar, red lead, hematite, orpiment, lead white, chalk, carbon black, azurite, and atacamite. Synthetic pigments include Hansa red, chrome yellow, titanium white, Prussian blue, ultramarine blue, phthalocyanine blue, emerald green, and phthalocyanine green. Indigo was found in certain areas. Degradation products such as lead sulfate and gypsum were also detected. The analysis suggests multiple creation periods for the patterns, providing evidence of historical restorations. Some patterns date to around the 45th year of the Qianlong period, while others might be from the Republic of China period (1912–1949 CE). This research offers insights into the conservation and restoration of the decorative patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prince Kung’s Palace, located in the Xicheng District of Beijing, stands as the most exquisite princely residence in Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE). With significant historical and cultural values, it has been designated as a first-class national museum and a 5A-class tourist attraction of China. The construction of the palace was initiated around 1780 CE by Ho-Shen, a minister under Emperor Qianlong. It nowadays spans an area of approximately 60,000 square meters1. The residence has housed notable figures including Minister Ho-Shen (1750–1799 CE), Princess Gulunhexiao (1775–1823 CE), Prince Qing Yonglin (1766–1820 CE), and Prince Kung Yixin (1833–1898 CE). As a fusion of a ministerial residence and a royal family mansion, Prince Kung’s Palace encapsulates a wealth of historical, cultural, and artistic legacies.

The architectural complex of Prince Kung’s Palace is adorned with a plethora of decorative patterns, which have undergone numerous restorations from the Qing Dynasty to the present, preserving a trove of historical information. The decorative patterns encompass the three official types commonly used during the Qing Dynasty: tangent circle pattern, dragons pattern, and Suzhou-style pattern. These patterns not only accentuate the noble status of the residents but also serve as invaluable resources for studying the cultural and artistic milieu of the era while preserving key information about the pigments prevalent during the Qing Dynasty. However, the enduring effects of natural elements, including rain, wind, sand, and sunlight, as well as human-induced factors, have led to significant degradation of the decorative patterns. The degradation is manifested as flaking, peeling, fading, and powdering, severely impacting the aesthetic appeal and value of the patterns. Consequently, there is an imperative need for identification and preservation measures for the decorative patterns. Pigment analysis is pivotal for the effective protection and restoration of these decorative patterns2,3,4.

Raman spectroscopy is a rapid, non-destructive, and micro-regional analytical technique. Combined with XRF, the multimodal method enables the swift and precise identification of the molecular fingerprints and elemental composition of materials2,4,5. At present, the combined use of portable Raman spectroscopy and handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry has been well-established in the field of mural research. For instance, M. Sawczak et al. used portable XRF and Raman techniques for non-destructive analysis of the murals of the Little Christopher chamber in the Main Town Hall of Gdańsk, Poland and successfully identified the pigments6. R. Alberti et al. analyzed archaeological samples from the Villa dei Quintili (II/III century A.D.) using handheld XRF and Raman spectrometer, identifying key pigments and their distribution in frescoes, pottery, and statues7. J. M. Madariaga et al. conducted in-situ analyses on the walls and wall paintings of two Pompeian houses using portable Raman and ED-XRF spectrometers, identifying key compounds in the efflorescence and assessing the effect of environmental factors on their formation8. These advanced techniques facilitate the non-invasive analysis of the paintings, allowing for the accurate identification of pigments without compromising the integrity of these invaluable artifacts.

This research represents the first application of portable Raman spectroscopy and handheld X-ray fluorescence for the non-destructive analysis of the architectural decorative patterns of Prince Kung’s Palace. The investigation primarily targets the pigments utilized in the artistic creation process, uncovering the embedded historical and cultural information. Furthermore, this research provides a scientific foundation for the conservation and restoration of these painted artworks.

Methods

Architectural decorative patterns of Prince Kung’s Palace

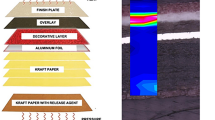

The research conducted a comprehensive scientific examination of the representative architectural decorative patterns within Prince Kung’s Palace. Figure 1 shows the architectural plan of Prince Kung’s Palace, in which architectures that have undergone non-destructive investigation are marked with colored boxes. The pictures of the decorative patterns in these architectures are shown in Fig. 2, which included the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a, g), the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b), the East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c), the West Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2h), the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d), the aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e), and the Duofu Hall (Fig. 2f). These structures are located on the east, west and middle roads of the palace, as well as the gardens, encompassing a broad area and showcasing a diverse array of decorative patterns. All in-situ measurement locations are marked with red boxes in Fig. 2, facilitating the precise documentation and analysis of the pigments without causing any disturbance to the integrity of the patterns.These locations encompass most of the colors that can be observed, including red, yellow, white, black, blue, and green.

Experimental techniques

The Raman spectroscopic analysis was conducted utilizing a portable spectrometer from EmVision LLC., America, which incorporates a thermoelectrically cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) detector. This detector is capable of achieving a cooling temperature as low as −60 °C, minimizing thermal noise thus enhancing the detection sensitivity. The spectrometer is designed to operate over a spectral range from 100 cm−1 to 2000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The system is equipped with a 785 nm semiconductor laser, which serves as the excitation source with an adjustable power output of up to 300 mW. Careful selection of the laser power during the measurement process is essential to prevent laser-induced damage to the decorative patterns, ensuring the preservation of the artwork’s integrity.

XRF analysis was performed using the Thermo Scientific Niton XL3t spectrometer, manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific in the USA. This high-performance handheld instrument employs a miniature X-ray tube with a gold target as the excitation source and was operated in soil mode during the in-situ analysis. The spectrometer is equipped with a high-performance silicon photodiode (Si-Pin) detector, which is capable of quantifying 32 elements across the atomic measurement range from sulfur (S) to bismuth (Bi). This comprehensive analytical capability provides valuable insights into the elemental composition of the pigments and substrates within the architectural decorative patterns.

Results

Through in-situ non-destructive analysis of the painted artwork in various buildings in the Prince Kung’s Palace, the pigments used in the different decorative patterns were successfully identified.

Red pigments

The red pigments were predominantly identified in the patterns of the intermediate purlin of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a–A4, A5, A7), the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b–B6, B9), the East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c–C3, C8), the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D2, D6, D8, D9), and the eaves outside the Aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e–E4, E7, E8). The corresponding Raman spectra for these areas are depicted in Fig. 3. The Raman bands at 252, 284, and 343 cm−1 in Fig. 3a align with those of cinnabar (HgS), induced that cinnabar was employed as the red pigment in these areas (as detailed in Table 1). The characteristic Raman peaks at 120, 150, 313, 390, and 548 cm−1 (Fig. 3b) confirm the presence of red lead (Pb3O4), thus affirming that red lead was used as a red pigment in the specified locations (points A5, A7, B9, C8, D2, D9, and E4 in Fig. 2). The Raman bands at 226, 294, 411, 497, and 615 cm−1, as illustrated in Fig. 3c, are distinctively attributed to haematite (Fe2O3)9, which were collected from the red area (point C3) in the East Imperial Gate Two. Furthermore, the bands observed at 341, 617, 797, 986, 1126, 1185, 1215, 1254, 1331, 1383, 1445, 1495, 1554, and 1617 cm−1 in Fig. 3d, obtained from the red areas (points D6 and D8) in the decorative patterns of the Hall of Mental Purification, are assignable to Hansa red (C17H13N3O3)9,10, with the band at 1087 cm−1 corresponding to chalk (CaCO3).

a Raman spectrum acquired from points of A4, B6, E7, E8; b Raman spectrum acquired from points of A5, A7, B9, C8, D2, D9, E4; c Raman spectrum acquired from point of C3 and (d) Raman spectrum acquired from points of D6, D8 (All the point labels A-H are shown in Fig. 2, the legends below is the same).

Cinnabar, red lead, and hematite have historically been common red pigments used in ancient times. Hematite and red lead were found in Cappadocian churches from the 6th to 13th centuries11. There are also many records of the application of cinnabar, red lead and hematite in archaeological materials12,13,14,15. Hansa red, a synthetic organic pigment derived from β-naphthol, was first synthesized in the early 20th century; however, it is rare to find Hansa red used as a red pigment in artworks10.

Yellow pigments

The Raman spectra of the yellow pigments, as depicted in Fig. 4, were collected from various locations, including the intermediate purlin of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a–A2, A9), the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b–B5), the East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c–C4), and the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D5). The Raman spectrum presented in Fig. 4a, obtained from the decorative patterns of the Baoguang Hall, First Palace Gate, and East Imperial Gate Two, exhibits characteristic bands at 136, 152, 177, 201, 291, 309, 354, and 382 cm−1, which are assignable to orpiment (As2S3)16. Therefore, we believe that orpiment is used as a yellow pigment in these places. In contrast, the Raman spectrum displayed in Fig. 4b, obtained from the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D5), reveals a distinct band at 841 cm−1, tentatively attributed to chrome yellow (PbCrO4)9,17. Complementary X-ray fluorescence spectroscopic analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 5, offers elemental confirmation of the presence of Pb and Cr elements in the yellow region at point D5 in Fig. 2d. This finding is consistent with the in-situ Raman analysis result, thereby confirming that chrome yellow is used as the yellow pigment in the decorative patterns of the Hall of Mental Purification.

XRF spectrum of the yellow area (D5) in the decorative patterns of the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d).

White pigments

The in-situ analysis of white pigments has been carried out across the white areas of the seven decorative patterns, which include the intermediate purlin of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a–A3), the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b–B7), East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c–C5, C9), the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D10), the eaves exterior of the Aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e–E1, E3, E6, E9), the beam of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2g–G1, G4), and West Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2h–H1). Totally, five different Raman results were found in these white areas (Fig. 6). Some white areas (points A3, B7, C5, C9, E1, E3, and E9) present a Raman band at 1050 cm−1 (Fig. 6a). It can be attributed to the v(CO32−) vibrational mode characteristic of lead white (2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2)15,18,19. As illustrated in Fig. 6b, the Raman bands at 281, 711, and 1086 cm−1, assignable to chalk, were found in the most white areas (as detailed in Table 1). Specially, it is inferred that chalk is the component of the ground layer material due to the peeling off of the pigment layer at the West Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2h–H1).

a Raman spectrum acquired from white areas of A3, B7, C5, C9, E3, E9, G4; b Raman spectrum acquired from white areas of A3, C5, C9, D10, E1, E3, E6, E9, G4, H1; c Raman spectrum acquired from white area of G1; d Raman spectrum acquired from white area of E9; e Raman spectrum acquired from white area of H1; f Raman spectrum acquired from black areas of B3, D4, E10, F3.

The Raman spectrum depicted in Fig. 6c exhibits bands at 142, 396, 513, 637, 684, 739, 773, 839, 1214, 1287, 1338, and 1538 cm−1. The bands at 142, 396, 513, and 637 cm−1 are attributed to titanium white (TiO2)20,21, while those at 684, 739, 773, 1214, 1287, 1338, and 1538 cm−1 correspond to the characteristic vibrational modes of phthalocyanine green (Cu(C32Cl16N8))9. The bands at 839 cm−1 belong to chrome yellow. Titanium white, phthalocyanine green and chrome yellow are all modern synthetic pigments, with synthetic dates of 1923, 1936 and 1809, respectively9, imply that the decorative patterns have been restored, and the restoration works must have occurred post-1936, as the pigments employed in these works were not available before this period. Hence, the white pigment used in the restoration process of the white area on the beam of the Baoguang Hall (point G1 in Fig. 2g) is titanium white, while phthalocyanine green and chrome yellow were accidentally mixed in. This hypothesis is substantiated by the observable presence of light green and yellow hues in the vicinity of the measuring point.

The Raman spectrum of the white regions within the decorative patterns of the Aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e) is showed in Fig. 6d. The Raman bands at 977, 1053, and 1086 cm−1 suggest different chemical compositions. Specifically, the bands at 1053 and 1086 cm−1 correspond to the vibrational modes characteristic of lead white (2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2) and chalk, respectively, while the band at 977 cm−1 is assigned to lead sulfate (PbSO4)22. The discovery of lead sulfate suggests the potential chemical degradation of lead white due to the presence of sulfur-containing pollutants23.

Furthermore, the Raman spectrum depicted in Fig. 6e presents a band at 1087 cm−1, which is assignable to chalk, and a band at 1008 cm−1, which is belong to gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O)24. The spectrum was obtained from the green area of the West Imperial Gate Two (point H1 in Fig. 2h), however only white pigments were identified. It is therefore inferred that the pigment layer in the measured area has peeled off, revealing the underlying ground layer, which is composed of chalk. The presence of gypsum is likely due to the chemical transformation of chalk, a process that is consistent with the degradation pathways described in the literature23,25.

Black pigment

The measurement points for the black areas are limited in number and are specifically situated at the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b–B3), Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D4), the eaves exterior of the Aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e–E10), and Duofu Hall (Fig. 2f–F3). The Raman spectrum of these black areas, as shown in Fig. 6f, reveals broad spectral bands centered at approximately 1322 and 1583 cm−1, which belong to characteristic Raman bands of amorphous carbon (C). The similar Raman spectra across all measured black areas suggest the employment of carbon black as the primary black pigment in these artworks. Historically, in ancient China, carbon black was a prevalent choice for black pigment in a diverse array of artistic creations, encompassing decorative patterns, murals26, and sculptures16,27.

Blue pigments

As shown in Fig. 2, it is evident that blue and green are the most prevalent colors in the decorative patterns. The in-situ analysis of blue areas was conducted across seven distinct decorative patterns, encompassing the intermediate purlin of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a–A6, A10), the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b-B1, B8), East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c–C2, C7, C10), Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D1, D11), the eaves outside the Aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e–E2, E5, E6), Duofu Hall (Fig. 2f–F2, F6), and the beam of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2g–G2, G3). We found four different blue pigments in the blue areas. The typical Raman spectra are presented in Fig. 7.

As depicted in Fig. 7a, the spectrum obtained from the blue areas (points C2, C7, C10, D1, D11, and F6 in Fig.1), exhibits a Raman band at 547 cm−1, which is assignable to the symmetric stretching vibration of S3− radical4,28. The presence of the S3− radical is characteristic of several blue pigments, including natural lapis lazuli ((Na,Ca)8(AlSiO4)6(S,SO4,Cl)1-2), synthetic ultramarine blue (Na6-10Al6Si6O24S2-4), and haüyne (Na6Ca2(Al6Si6O24)(SO4)2). Together with S2− ions, these Sx− species constitute the chromophores responsible for the vibrant blue coloration of these minerals. However, distinguishing among these potential pigment sources based solely on the S3− signature presents significant challenges. Accurate differentiation requires complementary ultraviolet (UV)-excited Raman spectroscopy, which can suppress chromophore resonance effects and provide detailed insights into the structural characteristics of the host aluminosilicate matrix29,30. Unfortunately, the portable Raman spectrometer employed in this study operates at a wavelength of 785 nm, limiting its capability to unequivocally assign the S3− anion to a specific pigment. Despite this analytical limitation, historical and economic considerations offer valuable context for pigment identification. Historically, lapis lazuli as a precious semiprecious stone, was extensively utilized in China prior to the Tang Dynasty. Its application in artwork declined due to its high cost, leading to the adoption of more economical alternatives such as azurite (2CuCO3·Cu(OH)2)31,32,33,34. Additionally, haüyne, recognized as one of the rarest gem varieties globally, has not been documented as a blue pigment in Chinese polychrome artworks35. In contrast, synthetic ultramarine blue, which closely mimics the color properties of natural lapis lazuli, was first synthesized in France in 1828. Its superior affordability and vivid coloration facilitated its widespread use during the late Qing Dynasty in China36. Empirical evidence supporting the prevalence of synthetic ultramarine blue includes its identification in numerous significant artworks, such as the murals of the Guandi Temple at Hujiapu, Xi’an—painted in 1881 CE during the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty37—as well as in portraits of Taoist figures from the late Qing Dynasty38 and statues restored in the Dunhuang Grottoes during the same period39. Furthermore, ultramarine blue has been detected in numerous decorative motifs from the Qing Dynasty era4,40,41. Given these historical precedents and the spectral data obtained, it is thus reasonable to infer that these blue areas analyzed predominantly employed synthetic ultramarine blue as the pigment. In Fig. 7b, the Raman bands at 549, 1086, 1312, and 1571 cm−1 are considered as indigo (C16H10N2O2), with the band at 1086 cm−1 correspond to chalk within the ground layer. Therefore, indigo is used as the blue pigment at point E6. Indigo, a plant-derived pigment renowned for its vivid blue hue and durability in artistic applications, extensively employed in murals, textiles, and other artifacts, such as those found in Cave 465 of the Mogao Grottoes42 and Tang Dynasty wooden painted artifacts from Xinjiang43.

The spectrum obtained from the areas corresponding to points B1, B8, E2, E5, F2, and G3 in Fig. 2, displays the bands at 272, 537, and 2133 cm−1, which are characteristic of Prussian blue (Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3·14-16H2O)17,44. For further confirmation, the XRF spectrum of the corresponding blue area is presented in Fig. 8a, revealing a pronounced Fe-Kɑ peak, thereby confirming that the blue pigment contain Fe element. This result is consistent with the Raman analysis. Prussian blue was first synthesized in Germany in 1704, then brought in China and extensively utilized in Qing Dynasty artworks, such as the blue pigments on the lacquer and gilded ink boxes from the Qianlong period (1736–1796 CE)45 and the restored Yongxin Palace in the Palace Museum during the Daoguang period (1821–1850 CE)40.

The Raman spectrum of the blue area (Fig. 2g–G2) is presented in Fig. 7d, with bands at 592, 682, 747, 775, 841, 953, 1142, 1342, 1451, and 1529 cm−1, which are assignable to phthalocyanine blue (CuC32H16N8)9. Phthalocyanine blue, synthesized in the early 20th century, is a prominent organic pigment. Due to its low cost and vibrant color, it is widely used in coatings, printing inks and fiber tinting, etc46,47,48.

In the blue areas of the intermediate purlin of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a–A6, A10), no corresponding Raman spectra were detected. However, the XRF spectrum, as shown in Fig. 8b, reveals a significant Cu element, indicating that the blue pigment used should contain Cu element. Given the historical context of the Qing Dynasty, where the widely used blue pigments included lapis lazuli, azurite, smalt (CoO·nSiO2), indigo, Prussian blue, and ultramarine blue36. Among these pigments, azurite is the only copper-containing pigment among them, it is deduced that the blue pigment in this instance is likely azurite. Azurite has been widely used in ancient colored paintings. It have been found in the murals of the Qutan Temple in Qinghai Province49 and the A-Er-Zhai Grottoes in Inner Mongolia50.

Green pigments

The nondestructive analysis of green areas within the decorative patterns was conducted at multiple locations, including the intermediate purlin of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2a–A1, A8), the First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b–B2, B4), East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c–C1, C6), Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d–D3, D7), and Duofu Hall (Fig. 2f–F1, F4, F5). The Raman spectrum of the green area corresponding to point F5 is presented in Fig. 9, revealing the bands at 684, 746, 775, 841, 1211, 1339, and 1538 cm−1. Among them, the bands at 684, 746, 775, 1211, 1339, and 1538 cm−1 belong to phthalocyanine green, while the band at 841 cm−1 is attributed to chrome yellow. The Raman spectrum of phthalocyanine green, as shown in Fig. 6c, was also detected at point G1 within decorative patterns on the beam of the Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2g).

Raman spectrum of green pigment acquired from the areas of F5 and G1 in Fig. 2.

Due to the stronger fluorescent background, suitable Raman spectra could not be obtained from other green areas. Consequently, elemental analysis of these regions was performed using XRF spectroscopy, with the corresponding spectra displayed in Fig. 10. The XRF spectrum obtained from the green areas (points A1, A8, B2, B4, F1, and F4 in Fig. 2), as shown in Fig. 10a, reveals the presence of Cu, and Cl elements. It indicates that the green pigment used should contain these elements. The XRF spectra of other green areas (points C1, C6, D3, and D7 in Fig. 2) reveal that the green pigment of these areas contains Cu and As elements (Fig. 10b). In ancient painting art, the common green pigments include malachite (CuCO3·Cu(OH)2), emerald green (Cu[C2H3O2]2·3Cu[AsO2]2), and atacamite (CuCl2·3Cu(OH)2)51. Among them, atacamite is characterized by the presence of both Cu and Cl elements, while emerald green contains both Cu and As elements. Therefore, the XRF spectra in Fig. 10a, b obtained from the green areas correspond to the pigments of atacamite and emerald green, respectively. Atacamite, a green pigment frequently employed prior to the late Qing Dynasty, has been identified in temple murals in Datong52 and in the ancient architectural decorative patterns of the Confucius Temple in Qufu53. Emerald green, a synthetic green pigment synthesized in 1814, was extensively utilized during the late Qing Dynasty due to its affordable price51. The use of two different green pigments with distinct time periods can serve as a marker for distinguishing the age of murals.

Discussion

The pigments characterized within the architectural decorative patterns of Prince Kung’s Palace are delineated in Table 1, It is observed that the pigments used in different decorative patterns are not consistent. Among the identified pigments, cinnabar, red lead, haematite, orpiment, lead white, chalk, lead sulfate, gypsum, and carbon black are prevalent in pre-modern artifacts, which complicates the precise dating of the decorative patterns. Nevertheless, the presence of contemporary synthetic pigments, including ultramarine blue, emerald green, Hansa red, Prussian blue, phthalocyanine green and phthalocyanine blue, provides pivotal evidence for discerning between modern restorations and ancient paintings.

The Baoguang Hall exhibits a diversity of blue pigments across its different sites, including azurite on the intermediate purlin (Fig. 2a) and a combination of Prussian blue and phthalocyanine blue on the beams (Fig. 2g). Azurite, a prevalent mineral pigment in antiquity, has a documented presence in the Tianti Mountain Grottoes54, A-Er-Zhai Grottoes in Inner Mongolia50, and the Eastern Thousand Buddha Caves in Guazhou55. Prussian blue, first synthesized in 1704, was introduced to China around 1775 and achieved domestic production by 182745,56,57. Phthalocyanine blue, synthesized in 1936, marks a more recent addition to the palette. The use of these three pigments, each from distinct historical periods, indicates that the decorative patterns in the Baoguang Hall underwent restoration on at least two occasions. The azurite-containing patterns on the intermediate purlin are likely original artworks from the Qianlong period around 1780 and have been well-preserved due to their elevated position above the ceiling. In contrast, the Prussian blue-adorned beams, situated below the ceiling, were likely repainted post-1827, with partial restoration employing titanium white and phthalocyanine blue post-1936. Collectively, the decorative patterns within the Baoguang Hall exhibit a combination of at least three periods of artworks, each utilizing distinct blue pigments.

The Prussian blue identified in the decorative patterns of First Palace Gate (Fig. 2b) aligns with that used in the unrestored areas of the beams of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2g) and Duofu Hall (Fig. 2f) and is consistent with the blue pigment on the outer eaves of the aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e). Notably, there is no evidence of other modern synthetic pigments in these areas except for the repair areas. This suggests that the decorative patterns in these locations should be painted during the same time range, specifically after 1827.

Conversely, the decorative patterns of East Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2c) exhibit a distinct palette, comprising ultramarine blue and emerald green. Ultramarine blue, synthesized in 1828 and introduced to China in 1860, and emerald green, synthesized in 1814 and widely adopted in the 1850s4,9,51, indicate that these patterns were drawn during the late Qing dynasty.

The pigments employed in the decorative patterns within the Hall of Mental Purification (Fig. 2d) are predominantly modern synthetic, including Hansa red and chrome yellow. The presence of Hansa red, which emerged in the early 20th century, suggests that the decorative patterns in the Hall of Mental Purification were repainted during the Republican era. In the decorative patterns on the eaves of the aisle of Baoguang Hall (Fig. 2e), two distinct blue pigments were identified: Prussian blue and indigo. The detection of indigo beneath the white pigment layer (Fig. 2e–E6) implies that it may have been overlaid during restoration. Prussian blue, which achieved domestic production around 1827, and indigo, a plant-derived pigment frequently utilized in antiquity, indicate that the color patterns on the eaves of the outer aisle of Baoguang Hall were restored post-1827. Additionally, lead white, chalk, and lead sulfate were identified on the white floral patterns (Fig. 2e–E9), with lead white as the pigment and chalk potentially as a ground layer material. The detection of lead sulfate is indicative of the degradation of lead white due to acidic environmental exposure23.

A variety of blue and green pigments were detected within the decorative patterns of the Duofu Hall (Fig. 2f). The extensive application of atacamite and Prussian blue suggests that the patterns were executed post-1827. Discernible traces of pigment smearing were observed in specific areas (Fig. 2f–F5, F6), where ultramarine blue and phthalocyanine green were identified, implicating subsequent restorative interventions. According to records, the Duofu Hall underwent restoration in 2003, which included the repair of its damaged and incomplete decorative patterns1. This historical account substantiates the aforementioned inference. The decorative patterns of West Imperial Gate Two (Fig. 2h) exhibit substantial pigment exfoliation, with chalk and gypsum detected, suggesting carbonate degradation under acidic conditions23,58.

This investigation utilized non-destructive analytical techniques, including Raman spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence, to perform an in-situ analysis of the pigments employed in the decorative patterns of Prince Kung’s Palace. The results revealed that the red pigments consisted of cinnabar and red lead, with minor quantities of haematite and Hansa red. The yellow pigments were mainly orpiment, accompanied by sporadic occurrences of chrome yellow. The white pigments encompassed lead white and titanium white, while chalk was identified in the ground layer. The degradation products of chalk and lead white, such as gypsum and lead sulfate, were discovered. Carbon black was identified as the black pigment. The blue pigments comprised azurite, Prussian blue, ultramarine blue, phthalocyanine blue, and indigo. The green pigments included atacamite, emerald green, and phthalocyanine green. Among these pigments, there are commonly used historical pigments such as cinnabar, red lead, azurite, and modern synthetic pigments phthalocyanine green, Hansa red, titanium white. The application of these pigments presents valuable historical markers for creation and restoration periods of the decorative patterns. This study provides comprehensive information of the pigments used in the decorative patterns of Prince Kung’s Palace, thereby enhancing the understanding of its historical and cultural significance, and providing critical knowledge for future conservation and restoration endeavors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Z. A Study on the Architectural Culture and Evolution of Prince Kung’s Palace (China Building Materials Press, 2014).

Ma, J. et al. In situ analysis of pigments on the murals of Yanshan Temple in Fanshi County, Shanxi Province, China by portable Raman and XRF spectrometers. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 138, 48 (2023).

Balakhnina, I., Anisimova, T., Mankova, A., Chikishev, A. & Brandt, N. Raman microspectroscopy of fresco fragments from the Annunciation Church at Gorodishche at Veliky Novgorod. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 136, 610 (2021).

Li, Y., Wang, F., Ma, J., He, K. & Zhang, M. Study on the pigments of Chinese architectural colored drawings in the Altar of Agriculture (Beijing, China) by portable Raman spectroscopy and ED-XRF spectrometers. Vib. Spectrosc. 116, 103291 (2021).

Machado, A. F. et al. Combining in situ elemental and molecular analysis: the Viceroys portraits in Old Goa, India. J. Cult. Herit. 68, 122–129 (2024).

Castro, K., Pérez-Alonso, M., Rodríguez-Laso, M. D., Etxebarria, N. & Madariaga, J. M. Non-invasive and non-destructive micro-XRF and micro-Raman analysis of a decorative wallpaper from the beginning of the 19th century. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 847–860 (2007).

Alberti, R. et al. Handheld XRF and Raman equipment for the in situ investigation of Roman finds in the Villa dei Quintili (Rome, Italy). J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 32, 117–129 (2017).

Madariaga, J. M. et al. In situ analysis with portable Raman and ED-XRF spectrometers for the diagnosis of the formation of efflorescence on walls and wall paintings of the Insula IX 3 (Pompeii, Italy). J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 1059–1067 (2014).

Burgio, L. & Clark, R. J. H. Library of FT-Raman spectra of pigments, minerals, pigment media and varnishes, and supplement to existing library of Raman spectra of pigments with visible excitation. Spectrochim. Acta. Part A57, 1491–1521 (2001).

Raicu, T. et al. Preliminary identification of mixtures of pigments using the paletteR package in R—the case of six paintings by Andreina Rosa (1924–2019) from the International Gallery of Modern Art Ca’ Pesaro, Venice. Heritage 6, 524–547 (2023).

Pelosi, C., Agresti, G., Andaloro, M., Baraldi, P. & Santamaria, U. The rock hewn wall paintings in Cappadocia (Turkey). Characterization of the constituent materials and a chronological overview. e-Preserv. Sci. 10, 99–108 (2013).

Idrissi Serhrouchni, G. et al. Investigation of inks, pigments and paper in four Moroccan illuminated manuscripts dated to the eighteenth century. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 136, 850 (2021).

Gao, Z. On the ancient sources of ocher, vermilion, red lead and its application. J. Qinghai Minzu Univ.37, 102–109 (2011).

Wang, J. & Wang, J. A survey on the application of cinnabar in ancient China. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 11, 40–45 (1999).

Manzano, E., Rodríguez-Simón, L. R., Navas, N. & Capitán-Vallvey, L. F. Non-invasive and spectroscopic techniques for the study of Alonso Cano’s Visitation from the Golden Age of Spain. Stud. Conserv. 66, 298–312 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Spectroscopic investigation and comprehensive analysis of the polychrome clay sculpture of Hua Yan Temple of the Liao Dynasty. Spectrochim. Acta. Part A 240, 118574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2020.118574 (2020).

Surtees, A. P. H., Telford, R., Edwards, H. G. M. & Benoy, T. J. Raman spectroscopic study of the pigments in a putative John Constable oil sketch. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 2228–2233 (2021).

Nastova, I. et al. Micro-Raman spectroscopic analysis of inks and pigments in illuminated medieval old-Slavonic manuscripts. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 1729–1736 (2012).

Tavitian, Y., Yancheva, D. Y. & Todorov, N. D. Three Persian Qajar paintings from the National Gallery Sofia. Study of the technology and the composition materials for the purpose of dating and conservation evaluation. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 136, 733 (2021).

Sbroscia, M. et al. Spectroscopic investigation of Cappadocia proto-Byzantine paintings. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 95–108 (2021).

Ma, H. The pigments analysis of the murals in the Temple of Dragon King at Beijin Village, Hunyuan County, Datong. Orient. Collect 17, 47–49 (2021).

Jiang, K., Sun, Y., Zhu, Z., Zhang, N. & Jin, W. Analysis of pigments and cementing materials for statue in Weikang Grotto, Thousand Buddha Cliff, Guangyuan. China Cult. Herit. 71–77 https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7819.2021.06.010 (2021).

Coccato, A., Moens, L. & Vandenabeele, P. On the stability of mediaeval inorganic pigments: a literature review of the effect of climate, material selection, biological activity, analysis and conservation treatments. Herit. Sci. 5, 12 (2017).

Prieto-Taboada, N. et al. Understanding the degradation of the blue colour in the wall paintings of Ariadne’s house (Pompeii, Italy) by non-destructive techniques. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 85–94 (2021).

Veneranda, M. et al. In-situ multianalytical approach to analyze and compare the degradation pathways jeopardizing two murals exposed to different environments (Ariadne House, Pompeii, Italy). Spectrochim. Acta. Part A. 203, 201–209 (2018).

Yuan, Y. & Wang, J. Scientific analysis of the mural pigments from Xu Xianxiu’s tomb of the Northern Qi Dynasty. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 32, 16–25 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Micro-Raman, XRD and THM-Py-GC/MS analysis to characterize the materials used in the Eleven-Faced Guanyin of the Du Le Temple of the Liao Dynasty, China. Microchem. J. 171, 106828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2021.106828 (2021).

Schmidt, C. M., Walton, M. S. & Trentelman, K. Characterization of Lapis Lazuli Pigments Using a Multitechnique Analytical Approach: Implications for Identification and Geological Provenancing. Anal. Chem. 81, 8513–8518 (2009).

Caggiani, M. C. & Colomban, P. Raman microspectroscopy for Cultural Heritage studies. Phys. Sci. Rev. 3. https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2018-0007 (2018).

Caggiani, M. C., Acquafredda, P., Colomban, P. & Mangone, A. The source of blue colour of archaeological glass and glazes: the Raman spectroscopy/SEM-EDS answers. J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 1251–1259 (2014).

Sun, Y., Jiang, K. & Zhang, N. Pigment analysis of Lotus Cave statues using Raman spectroscopy and microscopy. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 31, 77–85 (2019).

Luo, J. et al. The geological variations in the mineral pigment production in Asia and their impact on mural colors. Mineral. Petrol. 1–30 (2025).

Lai, S. et al. Mining and trading of ancient lapis lazuli: the exploration for a combination of twofold evidence based on historical documents and archaeology discovery. J. Gems Gemmol. 23, 1–11 (2021).

Wang, J. The Producing Area of Hecub a Juno application of Lapis Lazuli Pigment of polychrome arts on Ancient China. Relics Museol. 6, 396–402 (2009).

Lu, F. & Shen, X. The fluorescence spectra of gem-quality Hauyne. Spectrosc. Spectral Anal. 40, 3468–3471 (2020).

Ji, J. & Zhang, J. The origin and history of some blue pigments in Ancient China. Dunhuang Res. 6, 109–114 (2011).

Zhao, F., Feng, J., Sun, M., Wu, C. & Guo, R. The analysis and study on the pigments of the Murals of the Guandi Temple at Hujiapu in Zhouzhi, Xi’an. Relics Museol. 4, 95–100 (2017).

He, Y. et al. Non-destructive in-situ characterization of pigments on a portrait of Chinese Taoism figure. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 22, 235701 (2010).

Wang, J. Research on synthetic ultramarine pigments in the Dunhuang Grottoes. Dunhuang Res. 1, 76–81 (2000).

Yang, H. & Li, G. On the ages and crafts of the Haiman-Patterned Window Shelter of the Main Hall External of Yangxin Palace Complex. Palace Mus. J. 72–88 https://doi.org/10.16319/j.cnki.0452-7402.2022.01.006 (2022).

Zhuo, Y. & Wang, S. On The construction history and craftsmanship of the Polychrome Patterns on the Inner Eaves of the Rear Hall of Fengxian Dian in the Forbidden City. Palace Mus. J. 35–55. https://doi.org/10.16319/j.cnki.0452-7402.2024.10.009 (2024).

Li, D., Shui, B., Feng, Y., Shan, Z. & Yu, Z. A study on the pigments and painting technigues of the multi-colored Murals in Mogao Cave 465 and the effect on restoration. Res. Conserv. Cave Temples Earthen Sites. 1, 68–80 (2022).

Zheng, H. et al. Analysis of techniques and pigments used for colored clay sculptures excavated from the Tang Tomb at Astana, Xinjiang. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 25, 31–38 (2013).

Bell, I. M., Clark, R. J. H. & Gibbs, P. J. Raman spectroscopic library of natural and synthetic pigments (pre- ≈ 1850 AD). Spectrochim. Acta. Part A. 53, 2159–2179 (1997).

Zhang, T. The pigment analysis and reinforcement of the black lacquer and gold-outlined ink box with the Qianlong mark “Ze Gu Yi Qing” in the Qing palace collection. Identif. Apprec. Cult. Relics. 34–37. https://doi.org/10.20005/j.cnki.issn.1674-8697.2023.03.008 (2023).

Zhou, C. & Mu, Z. Organic Pigment Chemistry and Technology (China Petrochemical Press, 2002).

Yin, S., Wang, G., Liu, B., Hou, Q. & Ma, Z. Preparation and application of aqueous phthalocyanine blue pigment. Shanghai Dyest 52, 25–27 (2024).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Lv, T. & Yang, L. Research on improved synthesis of phthalocyanine blue pigment and its performance. Paint Coat. Ind. 44, 39–42 (2014).

Wang, J., Li, J., Tang, J. & Xu, Z. Research on the murals pigments of Qutan Temple, Qinghai. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 5, 23–35 (1993).

Zhang, S. et al. Micro-Raman Identification of the Wall-painting Pigments in A-Er-Zhai. Cult. Relics South. China, 108–112 https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-6275.2009.01.015 (2009).

Sheng, L., Zhang, T., Niu, G. & Wang, K. Spectral analysis of green pigments of painting and colored drawing in northern Chinese ancient architectures. Spectrosc. Spectral Anal. 30, 453–458 (2015).

Ma, H. Raman spectroscopic analysis of pigments commonly used in temple murals in Datong region. Identif. Apprec. Cult. Relics. 209, 96–98 (2021).

Li, J. The composition of pigments of decorative paintings on ancient buildings of Qufu’s Temple of Confucius. China Cult. Herit. Sci. Res. 4, 86–89 (2014).

Chen, G. Analysis of pigments and clay of the polychrome statue and wall paintings in the No.9 Tiantishan Grotto. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 22, 91–96 (2010).

Yang, T. et al Some Thoughts about the Material Analysis and In Situ Conservation of the Mural at the Eastern Thousand Buddha Caves in Guazhou. Relics Museol. 91, 99–104.https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-7954.2020.06.013 (2020).

Bailey, K. A note on Prussian blue in nineteenth-century Canton. Stud. Conserv. 57, 116–121 (2013).

Liu, C. & Liu, M. Craft application of Prussian Blue against the background of “Oversea Blue” use in Qing China. J. Chin. Archit. Hist. 2, 137–157 (2017).

Deneckere, A. et al. The use of a multi-method approach to identify the pigments in the 12th century manuscript Liber Floridus. Spectrochim. Acta. Part A. 80, 125–132 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Prince Kung's Palace Museum, Ministry of Culture and Tourism, China for providing research objects. This work is part of the project Research on Architectural Decorative Patterns in the Prince Kung's Palace (GBLXWF-2021-Z-01), and is funded by the Prince Kung's Palace Museum, Ministry of Culture and Tourism, China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 11874084).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. conducted data collection, data analysis and manuscript writing; Z.C. and X.H. helped to select suitable research objects and provided research ideas; S.G. supported the relevant information of Prince Kung’s Palace; J.M., Yan Li and W.Z. made in-situ measurements, including Raman and XRF experiments. F.W., Yan Li and Yu Li made revisions to the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., Gao, S., Li, Y. et al. Nondestructive analysis of architectural decorative patterns in Prince Kung’s Palace by Raman and XRF. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 226 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01800-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01800-0