Abstract

Heritage education has drawn increasing attention, with digital games and online courses emerging as innovative learning tools. However, the integration of asynchronous digital games and synchronous online courses remains underexplored. This study introduces Bichronous Modes (BMs) in heritage education, combining these two approaches to improve motivation, behavioral intentions for heritage preservation, and learning outcomes. Two experiments investigated the effectiveness of different learning sequences: BMgame-course (asynchronous games followed by synchronous courses) and BMcourse-game (synchronous courses followed by asynchronous games). Results indicated that BMs are more effective than using either approach alone. Specifically, BMgame-course facilitated heritage knowledge acquisition, while BMcourse-game improved student satisfaction. A structural equation model (SEM) revealed that satisfaction mediates the relationship between motivation and behavioral intentions for heritage preservation. This study highlights BMs’ potential in heritage education program design and suggests future avenues for refining learning mechanisms, emphasizing their applicability in schools and museums to promote sustainable heritage education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage education, defined as a learning approach grounded in cultural heritage, encompasses active educational methods, cross-curricular approaches, and collaboration among education and culture professionals1. As an essential component of contemporary educational practices, cultural heritage education offers profound insights into humanity’s history, traditions, and values2,3,4. Its importance is manifested in three main aspects: First, it enriches students’ historical knowledge by uncovering the historical contexts of heritage sites, the functions and craftsmanship of artifacts, and the essence of intangible cultural heritage5,6. This deepens students’ understanding of societal development, artistic expression, and technological progress. Second, it develops students’ awareness of cultural heritage protection5,7. It inspires students to become active participants in preserving cultural heritage for future generations by emphasizing the historical, cultural, and artistic significance of both tangible and intangible heritages8. Third, it strengthens students’ sense of identity and community cohesion by connecting individuals with their cultural roots, which fosters a sense of belonging and pride9. It also promotes social harmony by cultivating a shared awareness of heritage and collective memory, thereby fostering respect for diverse cultures and traditions10.

The digitalization of educational tools is increasingly being adopted in heritage education, driven by three key advantages11. First, it overcomes spatial and temporal limitations, providing diverse cultural heritage resources through digital and immersive formats, which is especially beneficial for accessing endangered sites and bridging regional disparities in heritage education12,13. Second, digital tools enhance student motivation by integrating high-quality, interactive resources such as multimedia, videos, images, and 3D models to create realistic virtual scenes14,15. This offers a comprehensive and vivid learning experience. Furthermore, digital tools provide personalized and self-directed learning opportunities that cater to individual learning styles and paces16. Finally, digital tools promote cognitive, practical, and comprehensive skill development through simulated environments17. For example, digital games allow students to simulate the restoration and protection processes of cultural heritage, fostering heritage protection awareness and improving practical and problem-solving skills18. Additionally, digital tools enhance students’ information literacy and critical thinking, supporting their overall development19.

Digital games and online courses serve as two prominent sub-frameworks in heritage education20. Digital games, offering an adaptive and interactive approach, can be classified into three categories based on their content focus21. The first category comprises games that focus on historical events and the progression of civilizations. For instance, in the game Civilization, players are encouraged to assume the roles of prominent historical figures, leading civilizations through conquest, diplomacy, scientific advancements, cultural development, and other means. Students engage with these digital games in their free time, followed by classroom learning or discussion, to facilitate their understanding of the fundamentals of civilization growth, development, and decline, and to enhance their critical and historical thinking regarding broader civilization trends22,23. The second category focuses on high-precision reproductions of tangible cultural heritage or scenarios. These games faithfully recreate specific historical periods, events, or processes. When physical remains are available, they are often digitally reconstructed with historically accurate details to enrich the experience24. Examples include the Animated Spatial Time Machine25, a collaborative platform involving students and citizens of Ghent, Belgium, aimed at achieving 3D heritage visualization. The third category centers on the restoration of intangible cultural heritage through narrative and emotional design26. For example, Tracers of the Past employs pre-constructed narratives divided into separate sections at different points of interest (POIs) within a cultural site. Players are tasked with uncovering the identities of three actual culprits while exploring an archeological site. This digital game is utilized in senior high school ancient Greek language and historiography courses, as well as in graduate e-learning programs27. However, the majority of reviewed digital games are primarily utilized within the contexts of history education and cultural tourism. Relatively few games have been explicitly designed for online learning, and even fewer have undergone rigorous scrutiny regarding their impact on attitudes toward cultural heritage.

Online courses represent another prominent sub-framework that has emerged in recent years and has been widely applied to heritage education. In the realm of informal education, museums have developed online courses to provide remote access to their exhibits and collections for diverse audiences28,29,30. For instance, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) offers online courses such as Art and Inquiry: Museum Teaching Strategies for Your Classroom and Art and Activity: Interactive Strategies for Engaging with Art, targeting museum educators and students31. Similarly, the North Carolina Museum of Art has implemented a “flipped museum” model to support online learning for high school students both before and after their museum visits32. Within formal education, online courses have been employed in archeology learning to share resources and enhance students’ practical skills. For example, the University of Leicester has developed courses such as England in the Time of King Richard III and Behind the Scenes at the 21st Century Museum, which emphasize the integration of complementary skills and experiences between universities and museums. This approach enables heritage education to bridge theory and practice. In China, several heritage courses are available on Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) platforms, including Cultural Heritage and Natural Heritage (China University of Geosciences), Cultural Heritage and Natural Heritage (Huazhong University of Science and Technology), and Architectural Heritage Conservation (Zhengzhou University). Despite the proliferation of online courses, few have been utilized to evaluate the effectiveness of the synchronous learning process or combined with digital games.

From an educational perspective, the pedagogical strategies employed by teachers in heritage education play a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of digital games and online courses33. These strategies often have a more significant impact on educational outcomes than the content of the tools themselves. Previous studies have demonstrated that the use of digital games or online courses in isolation has significant limitations34,35. Given that heritage education is a comprehensive process requiring well-planned learning strategies, it should incorporate approaches that integrate the learning processes of digital games and online courses5. Cuenca-López’s advocates for a problem-solving approach in heritage education, emphasizing motivation and heritage contextualization in learning unit design. He views sequenced learning activities as progressing through stages like planning, searching, structuring, and evaluating36. Meanwhile, McCall presents a four-step loop for integrating games into history learning, stressing initial steps of studying historical materials and acquiring gaming skills. He suggests playing games before evidence analysis enhances contextual understanding and question-raising, while researching before playing may better familiarize students with specific evidence37. However, existing frameworks for integrating these two modalities lack a detailed examination of the optimal sequence for combining digital games and online courses. Furthermore, empirical studies on the learning sequences of digital games and online courses for heritage education are currently limited.

To address these gaps, this paper introduces the concept of “bichronous modes (BMs),” which refer to the integration of asynchronous digital games and synchronous online courses, designed to enhance heritage education. This concept is grounded in the framework of bichronous online learning38,39,40. Three key aspects define BMs in this study. First, BMs are constituted by combining synchronous online courses and asynchronous digital games. Within this framework, students actively engage with instructors through real-time, shared meetings while independently controlling their interactions with the digital games. Second, BMs treat digital games and online courses as two distinct yet equally vital components, rather than integrating one into the other. Although gamified approaches that embed games within online courses have been explored41,42, the synergistic effects of combining online courses and digital games remain underexplored empirically43. Third, the learning structure of BMs emphasizes instructional design. BMs can be implemented in two sequences: digital games followed by online courses, or online courses followed by digital games. These different sequences are likely to produce varying educational outcomes, which is a primary objective of this study.

The objective of this study is twofold. Firstly, it aims to explore the learning efficacy of digital games, online courses, BMgame-course, and BMcourse-game, with efficacy measured in terms of motivation, behavioral intention for heritage preservation, and scores. Secondly, it delves into the learning mechanisms specific to each educational modality, especially if disparities are identified in the first part of the inquiry. This study employs a structural equation model (SEM) and multi-group analysis to examine the learning mechanisms. The results indicate that the sequence of BMs significantly influences student satisfaction and the acquisition of heritage knowledge. Furthermore, the underlying mechanism linking motivation, behavioral intention for heritage preservation, and scores has been evaluated across various learning modes.

Methods

Overall research framework and hypotheses

The objectives of heritage education can be categorized into three core dimensions: enhancing motivation, cultivating behavioral intentions for heritage preservation, and improving performance outcomes4. Extensive research across diverse educational domains has consistently demonstrated a significant correlation among these three components44,45,46. Given this established framework, the present study aims to investigate whether these associations are similarly applicable within the context of heritage education and to explore the potential influence of different learning modalities on this underlying mechanism.

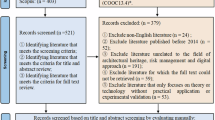

Building upon these considerations, this paper posits the following two research questions (see Fig. 1). RQ1: How do different learning modes (digital games, online courses, BMgame-course, and BMcourse-game) affect students’ motivation, behavioral intention for heritage preservation, and scores? RQ2: What are the underlying mechanisms linking motivation, behavioral intention for heritage preservation, and scores in different learning modes?

A structural equation model (SEM) and six hypotheses were proposed to elucidate the underlying mechanism linking motivation, behavioral intention of heritage preservation, and score (see Fig. 2). For the assessment of motivation, the Attention, Relevance, Confidence, Satisfaction (ARCS) model was employed. The ARCS model has been demonstrated to be effective in evaluating students’ motivation in online learning contexts47. It has also yielded notable results in previous heritage education studies48,49.

The ARCS model is grounded in expectancy-value theory, which posits that human behaviors are evaluative outcomes based on expectations (beliefs), the perceived probability of success (expectancy), and the perceived impact of success (value)50. According to the ARCS model, learning motivation is contingent upon four dynamic perceptual components: attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction51. Specifically, attention involves capturing learners’ interest and stimulating their curiosity for learning; relevance entails addressing learners’ personal needs to foster a positive attitude; confidence involves instilling learners with the belief in their ability to succeed and control their success; and satisfaction reinforces accomplishment with rewards (both internal and external).

Furthermore, these four components are categorized into two distinct processes within the ARCS framework: Motivational Processing and Outcome Processing, each serving different roles in learner motivation. Attention, Relevance, and Confidence are classified as Motivational Processing, which helps learners identify achievable performance goals. Satisfaction is considered Outcome Processing, which evaluates the balance between invested effort and final performance52,53. By differentiating between Motivational Processing and Outcome Processing, the ARCS model enables educators to gain a comprehensive overview of the major dimensions of learner motivation and to develop targeted strategies in each area to sustain and enhance motivation.

The behavioral intention of heritage preservation is defined as individuals’ belief that they should take action to comply with the rules of heritage protection and encourage others to participate in heritage preservation efforts. This behavioral intention has been emphasized in numerous international documents. For instance, the Athens Charter (Article 7) recommends that educators “…teach [individuals] to take a greater and more general interest in the protection of these concrete testimonies of all ages of civilization.” Similarly, the Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention, Article 12) states that “…[all should be] encouraged to participate in the process of identification, study, interpretation, protection, conservation, and presentation of cultural heritage.”

In the context of heritage education, particularly in environmental education, motivation has been shown to significantly influence behavioral intention. For example, generative motivation, such as educational motivation, has been demonstrated to affect the behavioral intention of environmental protection54. The motivation triggered by the expectation to acquire knowledge can be translated into the behavioral intention of heritage preservation. Thus, hypothesis 1 (ARCS Model -Low effort behavioral intention) and hypothesis 2 (ARCS Model -High-effort behavioral intention) are proposed.

Motivation is also likely to influence students’ scores in heritage knowledge. Heritage knowledge refers to the use of heritage as a tool to enhance learning outcomes55, such as facilitating the development of historical thinking and consciousness. Empirical evidence has demonstrated the impact of the ARCS model on scores56. Additionally, a greater understanding of heritage knowledge has been shown to enhance awareness of the value of cultural heritage protection57. Thus, hypothesis 3 (ARCS Model -Score) is proposed.

In the Theory of Motivation, Volition, and Performance (MVP), motivational processing (ARC) is theorized to impact the outcome processing (S), a relationship that has been empirically validate58. Students’ heritage knowledge and behavioral intention for heritage preservation can be enhanced through age- and level-appropriate instructional methods59. Consequently, higher levels of student satisfaction with their learning experiences are likely to improve both their performance and behavioral intention for heritage preservation. Therefore, satisfaction is proposed to mediate this relationship, leading to hypotheses 4, 5, and 6.

Measurements

Measurements in this study consisted of three components: the ARCS motivational scale, the behavioral intention of heritage preservation scale, and knowledge questions. The original and modified scales were translated into Chinese, adhering strictly to the “Back-Translation” standard60. See Table S1 (Supplementary Information) for the scales.

In this study, the motivational scale was adapted from Keller’s Instructional Materials Motivation Survey (IMMS) and the ARCS literature61. Fourteen items assessed motivational processing (attention, relevance, confidence), and four items assessed outcome processing (satisfaction). The questionnaire employed a five-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponded to “strongly disagree” and 5 corresponded to “strongly agree.”

Four 5-items measured attention which was adapted from Huang et al. 58 and Tsai & Liao62 to measure the level of attention of students. Example questions such as “The content is eye-catching”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.833. Relevance comprised six 5-items, which were adapted from Martí-Parreño et al. 63 and Ucar & Kumtepe64 to measure the level of relevance of students. Example questions such as “ The content is relevant to my interests”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.879. Confidence consisted of four 5-items, which were adapted from Huang et al. 58 and Tsai & Liao62 to measure the level of confidence of students. The scales were negatively phrased and rated in reverse. Example questions such as “It was more difficult to understand than I would like for it to be”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.806. For outcome processing, four 5-items measured satisfaction. The scales were adapted from Tsai & Liao62 to measure the level of satisfaction of students. Example questions such as “The feedback helped me feel rewarded for my effort”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.830.

The Environmental Responsibility Scale is often used in the education area to assess individuals’ pro-environmental behavioral intention65. The scales for measuring students’ behavioral intentions of heritage preservation were adapted from the instruments developed by Cheng et al. 66, Gursoy et al. 67, Ramkissoon et al. 68, and Wang et al. 69. The behavioral intention of heritage preservation is divided into low and high effort behavioral intention. Four 5-items pertained to low effort behavioral intention of students’ heritage preservation, in which the example question includes “I will read the reports or books about porcelain conservation and craft inheritance”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.830. High-effort behavioral intention used four 5-items to measure the high level of students’ heritage preservation. The example question includes “I will write letters in support of porcelain protection”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.844.

The students’ test scores were evaluated through a set of 30 single-choice questions, each allocated a maximum of 1 point, designed to assess their acquisition of two primary categories of knowledge: declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge70,71. The total possible score was 30 points. Declarative knowledge encompassed facts about porcelain, kiln sites, and handicraft types. For example, one question was: “In which dynasty was the blue-and-white porcelain of Jingdezhen kiln first fired? A. Song Dynasty B. Yuan Dynasty C. Ming Dynasty D. Qing Dynasty.” Procedural knowledge pertained to the processes of porcelain making and the handling of special conditions. An example question was: “How was the ancient plum bottle glazed? A. By dipping B. By pouring C. By brushing D. By spraying.” The Cronbach’s α of the scores at different times was 0.801, indicating that the questionnaires were reliable. See Supplementary Information (Section 1, Tables S2–S4) for other reliability indexes. The content of the questionnaires in the three tests was identical, but the sequence varied. Since the terminology of knowledge was taught in Chinese, the original items were developed by four Chinese researchers and then translated into English by another bilingual researcher.

The porcelain heritage digital game and online courses

Ancient porcelain occupies a pivotal position in China’s cultural heritage, epitomizing the unique history of the global handicraft industry. However, modern kilns encounter significant challenges in replicating the ancient porcelain manufacturing process. Moreover, the complexity of the porcelain production process makes it difficult for students to fully comprehend through traditional oral teaching alone. To address these issues, a porcelain heritage digital game and a series of online courses were developed and subsequently integrated into cultural heritage education programs.

The porcelain heritage digital game was meticulously constructed to replicate ancient porcelain-producing equipment and processes. It was designed based on a comprehensive synthesis of existing knowledge, including historical documents, archeological findings, and the latest research. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the game simulates the entire porcelain production process, encompassing material mining, preparation, molding, decoration, and firing. Throughout this process, students are empowered to make independent choices, leading to varied outcomes (see Fig. 4a, b). Subsequently, a virtual craftsman provides relevant explanations. For example, students are required to judge the kiln temperature by observing samples and determine the optimal time to cease firing (see Fig. 4c, d). These decisions result in the creation of different porcelain products. In summary, the porcelain heritage digital game is anticipated to serve as an effective tool to enhance students’ learning motivation and, in turn, influence their behavioral intentions regarding the preservation of porcelain heritage.

a Mining interface with raw materials and a cart for collection. Students can drag porcelain-making raw materials into the cart. After dragging correct or incorrect materials, the virtual craftsman prompts and explains. b Crushing interface showing tools and assembly instructions. Students must assemble and start the water-powered trip hammer to crush raw materials. c Firing interface with kiln controls and a temperature gauge. Students need to adjust the kiln temperature to fire porcelain. d Fining interface for glazing color comparison. Students observe sample colors to determine heat control during firing. Throughout these steps, students complete tasks independently but can seek hints from the virtual craftsman when needed.

A series of online courses was developed, comprising 12 sessions: one introductory session, three sessions dedicated to the typical kiln-making technology of the Song Dynasty, five sessions focused on the typical kiln-making technology of the Yuan Dynasty, and three sessions covering the typical kiln-making technology of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. For this experiment, the introductory session and the Jingdezhen Kiln porcelain-making technology were selected for testing, encompassing a total of four lessons (see Fig. 5). The introduction concentrated on the fundamental process of porcelain-making in ancient China. The Jingdezhen Kiln porcelain-making technology course encompassed three distinct segments of different porcelain products: raw material collection and processing, molding, and firing. The content of the online courses was delivered in a variety of formats, including text, images, GIFs, and videos, complemented by teachers’ online explanations.

a Material preparation steps, including shaping clay into a lotus form and making Dun. The teacher explains clay preparation and kneading techniques. b Molding process combining historical records and modern demonstrations. The teacher explains porcelain formation using ancient literature and videos of intangible cultural heritage inheritors. c Firing process showing temperature effects and kiln usage. The teacher links glaze color to firing temperature using ancient records and specimens from intangible cultural heritage practices.

In summary, both the digital game and the online courses share certain similarities and differences. The digital game offers a more enjoyable experience, with a specific focus on a typical artifact and more detailed procedural knowledge. Conversely, the online courses provide a more comprehensive, systematic, and in-depth knowledge base, albeit with a more specialized focus.

Participants and procedure

Heritage education addresses diverse audiences, including students of various ages72, community residents73, and tourists. While research has extensively covered heritage education in primary and secondary schools6,74, higher education in this field has gained relatively less attention75,76. Nevertheless, examining heritage education for college students is highly important for three key reasons. First, strengthening the university-level education for students majoring in cultural heritage and related disciplines is crucial, as it equips them with the expertise and professional skills needed for careers in heritage conservation and management8. Second, the complex and interdisciplinary nature of heritage knowledge requires advanced learning capabilities, making college students well-suited to grasp its intricacies. Third, from a social communication perspective, college students play a key role in spreading heritage knowledge and conservation awareness across society.

Based on these considerations, the study selected college students as participants and applied the following selection criteria. First, undergraduate students currently enrolled in cultural heritage, archeology, history, art, education, Chinese language and literature, or related disciplines were chosen. These students possess foundational knowledge of and show interest in heritage education, which enables them to engage effectively with the research content. Second, participants were required to have basic computer skills and access to online learning resources. Given that the research was conducted entirely online and necessitated independent task completion, these skills were essential. Third, priority was given to students with no prior experience in similar heritage education research to ensure the purity of the data.

For sampling, the study employed convenience sampling. Collaborating with universities in Tianjin, Shandong, Henan, and Jiangxi, the research targeted undergraduate students from various regions of China. Students who volunteered after being informed of the research purpose and requirements were included in the experiment. Each participant received a 20-yuan reward upon completing the experiment to compensate for their time and effort. The experiment was conducted online from September to November 2024.

In summary, selecting undergraduate students as participants aligns with the research goals of this heritage education study. Their relative homogeneity facilitates result comparison and analysis. Additionally, the geographic diversity of the selected universities enhances the applicability and representativeness of the research findings.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the students were randomly divided into two experimental groups. Initially, both groups were introduced to BMs and questionnaire completion. Over the six-week period, both groups underwent BMs in distinct sequences. In the Group BMcourse-game, students first completed the initial questionnaire. They then participated in four weeks of synchronous online courses, each 30-min session conducted under the instructor’s guidance. Upon completing the online courses, students filled out the second questionnaire. This was followed by a two-week period of asynchronous digital game activities, during which students could learn at their own pace. Finally, students completed the third questionnaire.

Correspondingly, in the Group BMgame-course, students also completed the first questionnaire before the experiment. They then engaged in digital games for two weeks, following the same rules as the Group BMcourse-game. After completing the digital games, students filled out the second questionnaire. This was followed by four weeks of synchronous online courses. Finally, students completed the third questionnaire.

Throughout the research process, strict adherence to the local university’s code of research ethics was maintained. Given that the study exclusively involved adult participants over the age of 18, formal approval from the local ethical committee was deemed unnecessary. Prior to participation, all subjects were provided with comprehensive information regarding the purpose of the research, the principles of research ethics, and the measures ensuring privacy and confidentiality. Informed consent was subsequently obtained from each participant.

The final sample included 349 students. After deleting observations with missing values, the valid sample comprised 336 students, including 174 in Group 1 (51.78%) and 162 in Group 2 (48.21%). The sample consisted of 75 males (22.3%) and 261 females (77.7%). The mean age of the sample was 20.46 years (SD = 1.403). Baseline analysis showed no significant differences in gender, age, initial score, and low and high effort behavioral intention (Tables S5–S7, Supplementary Information).

Analysis methods

SPSS26.0 and AMOS24.0 were employed for statistical analysis in this study. Firstly, Harman’s single-factor test was used to evaluate common method bias. Confirmatory factor analysis, composite reliabilities, and average variance were utilized to assess scale reliability and construct validity.

Guided by the research questions, the data analysis process comprised two parts (see Fig. 1). To address the first research question, an independent sample T-test was conducted to evaluate the effects of different learning modes on motivation, behavioral intentions, and scores.

For the second research question, SEM and multiple-group analysis were employed to analyze the relationships among variables. The model investigated the total, direct, and indirect effects of motivation on behavioral intention and score. Model fit was assessed using the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the normed fit index (NFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). At last, multiple-group analysis was employed to examine the mechanism of SEM in different learning modes for the second research question. Model fit was assessed with the NFI and the incremental fit index (IFI).

The rationale for using SEM and multiple-group analysis aligns with the second research question. SEM is a comprehensive statistical method that analyzes complex relationships among multiple variables within a unified framework. It is particularly suitable for models incorporating both latent and observed variables77. In this study, SEM is employed to investigate the relationships among students’ motivation, satisfaction, behavioral intention, and score. The methodology of SEM comprises two integral parts: the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model delineates the relationship between latent variables and their observed indicators, for example, the latent variable of satisfaction is reflected through multiple specific observed indicators, such as questionnaire items. The structural model, on the other hand, describes the causal relationships between latent variables, such as the influence of motivation on satisfaction and the subsequent effect of satisfaction on behavioral intention. and the structural model, which describes the causal paths between latent variables. The application of SEM can estimate the magnitude and significance of path coefficients, thereby uncovering the direct, indirect, and total effects between variables.

Multiple-group analysis, an extension of structural equation modeling (SEM), divides the sample into distinct subgroups based on a designated grouping variable. It constructs identical SEM models for each subgroup and compares model parameters across these subgroups78. By systematically testing configural, metric, scalar invariance, and structural covariance invariance, this method elucidates similarities and differences in latent variable relationships79. In this study, multiple-group analysis is employed to investigate whether the mediating role of satisfaction in the relationship between motivation and behavioral intentions remains consistent across the two learning modes (BMgame-course and BMcourse-game).

Results

Common method bias

Harman’s single-factor test is utilized to test common method bias. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is performed on all scale items as suggested by Podsakoff et al. 80. Six common factor eigenvalues are greater than 1.0, and the cumulative percent of variance is 66.629%. The first unrotated factor illustrates only 34.085% of the variance in this research, and there is not a single factor explaining the majority of the factors’ variance.

Scale reliability and construct validity

Model fitness, construct reliability and validity, and discriminant validity are used as criteria to test the measurement model in this study. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is conducted to test the validity and unidimensionality of the measurement scales (Table 1). According to Hu & Bentler81 and Byrne82, the model shows a reasonably good fit to the data (χ2 = 411.136, DF = 284, χ2/DF = 1.448 < 3, RMSEA = 0.037 < 0.05, GFI = 0.917 > 0.9, NFI = 0.903 > 0.9, TLI = 0.963 > 0.9, CFI = 0.968 > 0.95). Therefore, the confirmatory factor analysis model of this study can be supported by data, and the model structure validity is good.

Convergence validity should also be examined before analyzing the relationships between the latent constructs in the structural model (Fornell & Larcker)83. As shown in Table 2, the variables load well to their assigned factors with loading values between 0.665 and 0.838, which satisfactorily exceed 0.6. Composite reliabilities (CR) are higher than 0.7, which confirms the internal reliability of each construct (Bagozzi & Yi)84. The latent variables are found to explain more than half of the indicators’ variance, as the average variance extracted (AVE) values range from 0.512 to 0.577, which exceeds the cut-off value of 0.5. Thus, the results indicate that the constructs exhibit a sufficient degree of convergent validity.

Discriminant validity is another criterion to examine, which is judged by comparing the square root of AVE with a correlation between the construct and other constructs in the model. As depicted in Table 3, the square roots of AVE values exceed the between-factor correlations in each construct. Thus, the factor constructs are assessed as demonstrating adequate discriminant validity.

Study 1: Comparison of learning effectiveness

The differences between digital games and online courses are shown in the second test (Table S8, Supplementary Information). The results are summarized in the following two points. First, there are significant differences in scores (t = −11.921, P < 0.001) and changes in the score (t = −11.153, P < 0.001) between the two groups. The score and changes in the score are significantly higher in the group of digital games. Second, there are significant differences in attention (t = −4.718, P < 0.001), relevance (t = −2.117, P = 0.035), and satisfaction (t = –2.504, P = 0.013) between the two groups. Attention, relevance, and satisfaction are significantly higher in the group of digital games. Moreover, there are non-significant differences in other variables (P > 0.05). Generally, digital games have advantages over score and learning motivation compared with online courses.

The first group implements the BMcourse-game, and the second group is the BMgame-course. The differences between BMs are presented in the third test (Table S9, Supplementary Information). There are significant differences in scores (t = −2.464, P = 0.014) and the change in score (t = −2.748, P = 0.006) between the two groups. The third score of BMgame-course is better. The change in score is significantly higher in BMcourse-game. Meanwhile, there are significant differences in satisfaction (t = −2.731, P = 0.007), and the satisfaction of BMcourse-game is significantly higher. In addition, there are non-significant differences in other variables (P > 0.05). Therefore, the results reveal that the BMgame-course is conducive to scores. However, implementing BMcourse-game benefits students’ satisfaction.

Study 2: Mechanism research

Pearson correlation coefficients, means, and standard deviations are shown in Table 3. Based on the correlational analysis, there are positive correlations among variables in the SEM. Attention correlates weakly positive with all satisfaction, score, and low and high effort behavioral intentions. Relevance correlates moderately positively with satisfaction, low and high effort behavioral intentions, and weakly positively with the score. Confidence correlates moderately positively with low and high effort behavioral intentions, and weakly positively with satisfaction and score. Meanwhile, satisfaction is moderately positively associated with low effort behavioral intention, high effort behavioral intention, and score.

The data from the third test, in which both groups experienced the BMs, were utilized. A mixed variable Structural Equation Model was established, which includes several factors: attention, relevance, confidence, satisfaction, low-effort behavioral intention, high-effort behavioral intention, and score. Based on the fit indices (χ² = 430.387, DF = 304, χ2/DF = 1.416 < 3, RMSEA = 0.035 < 0.05, GFI = 0.916 > 0.9, NFI = 0.902 > 0.9, TLI = 0.964 > 0.9, CFI = 0.969 > 0.95), it was concluded that the hypothesized model fits the sample data fairly well.

As shown in Fig. 7, 49.7% of the variance of satisfaction is attributed to attention, relevance, and confidence. 42.8% of the variance of low effort behavioral intention is explained by attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction. 47.2% of the variance of high effort behavioral intention is explained by attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction. 28.5% of the variance of the score is explained by attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction.

Attention has a non-significant effect on low effort behavioral intention (P = 0.891) and high effort behavioral intention (P = 0.701). However, attention has a significant positive effect on score (β = 0.201, P < 0.001). In other words, more attention to perception is not effective in improving students’ low and high effort behavioral intentions, but benefits students’ scores. Thus, H1a and H2a are not supported, and H3a is supported. Meanwhile, the effects of relevance on the three variables reach statistical significance. Specifically, relevance significantly and positively influences low effort behavioral intention (β = 0.192, P = 0.010), high effort behavioral intention (β = 0.231, P = 0.001), and score (β = 0.159, P = 0.024). In other words, students with a high perception of relevance exhibit significantly higher levels of both low-effort and high-effort behavioral intentions, as well as higher scores, compared to their low-relevance counterparts. Thus, H1b, H2b, and H3b are all supported. Similarly, the influence of confidence on the three variables reaches statistical significance, which reveals that confidence is able to predict low effort behavioral intention (β = 0.345, P < 0.001), high effort behavioral intention (β = 0.381, P < 0.001), and score (β = 0.198, P = 0.001). Therefore, H1c, H2c, and H3c are all supported.

Furthermore, attention (β = 0.279, P < 0.001), relevance (β = 0.478, P < 0.001), and confidence (β = 0.182, P = 0.002) have significant positive effects on satisfaction. When attention increases by 1 unit, satisfaction increases by 0.279 units. When relevance increases by 1 unit, satisfaction increases by 0.478 units. When confidence increases by 1 unit, satisfaction increases by 0.182 units. Moreover, satisfaction has a significant positive effect on low effort behavioral intention (β = 0.279, P = 0.002), high effort behavioral intention (β = 0.240, P = 0.004), and score (β = 0.173, P = 0.034). When satisfaction increases by 1 unit, low effort behavioral intention increases by 0.279 units, high effort behavioral intention increases by 0.240 units, and score increases by 0.173 units. The result indicates that outcome processing will be promoted when students’ motivational processing is improved, thereby contributing to students’ behavioral intention of heritage preservation.

In this study, 5000 bootstrap samples are used to test the mediating effect (Mackinnon et al.)85. In the case of 95% confidence intervals (see Table 4), the results can be summarized as three core aspects. First, attention has significant indirect effects on low effort behavioral intention (Effect = 0.078, 95% CI = [0.023, 0.166]) and high effort behavioral intention (Effect = 0.067, 95% CI = [0.021, 0.146]) via satisfaction. Meanwhile, the indirect effect on low effort behavioral intention accounts for 89.7% (0.078/0.087) of the total effect, and high effort behavioral intention accounts for 74.4% (0.067/0.090). However, attention has a non-significant indirect effects on score via satisfaction (95% CI = [−0.002, 0.126]). Therefore, H4a and H5a are both supported, and H6a is not supported.

Second, relevance has significant indirect effects on low effort behavioral intention (Effect = 0.133, 95% CI = [0.049, 0.245]) and high effort behavioral intention (Effect = 0.151, 95% CI = [0.035, 0.234]) via satisfaction. Besides, the indirect effect on low effort behavioral intention accounts for 40.9% (0.133/0.325) of the total effect, and high effort behavioral intention accounts for 33.2% (0.115/0.346). However, relevance has non-significant indirect effects on score via satisfaction (95% CI = [−0.007, 0.243]). Therefore, H4b and H5b are both supported, while H6b is not supported.

Third, confidence has significant indirect effects on low effort behavioral intention (Effect = 0.051, 95% CI = [0.014, 0.115]) and high effort behavioral intention (Effect = 0.044, 95% CI = [0.011, 0.100]) via satisfaction. Moreover, the indirect effect on low effort behavioral intention accounts for 12.9% (0.051/0.396) of the total effect, and high effort behavioral intention accounts for 10.4% (0.044/0.424). Nevertheless, confidence has a non-significant indirect effects on score via satisfaction (95% CI = [−0.001, 0.092]). Therefore, H4c and H5c are both supported, while H6c is not supported.

The multiple-group analysis evaluates the mechanism of the Structural Equation Model in different learning modes. The model fit index is used to compare the differences between the models in this study. The criterion of NFI (ΔNFIå 0.02) and IFI (ΔIFIå 0.02) is followed to determine whether the decrement in fit is relevant (Meade et al.). The model fit indicators show that the measurement model of this study is invariant (Δχ2 = 26.261, ΔDF = 15, P = 0.035 < 0.05, ΔNFI = 0.036å 0.02, ΔIFI = 0.036å 0.02).

Then, the multiple-group analysis is performed by the coefficient of the two groups. The relative magnitudes of the regression coefficients in the two models, as well as the magnitudes of these coefficients relative to their standard errors, are compared86,87. The results indicate that there are significant differences between models in different learning methods, which are tested at Time 2 (Table S10, Supplementary Information). The influence of attention on satisfaction is significant in online courses (P = 0.003). Meanwhile, satisfaction significantly contributes to low effort behavioral intention in the group of digital games (P = 0.027). There are non-significant differences in other paths (P > 0.05).

Additionally, the results of the models in different BMs are non-invariance (Δχ2 = 19.454, ΔDF = 15, P = 0.194å 0.05) (Table S11, Supplementary Information). Therefore, it indicates that there is a non-significant difference between models under different learning sequences.

Discussion

This study addresses two critical research questions in heritage education. The first research question (RQ1) examines the impact of different learning modes—digital games, online courses, BMgame-course, and BMcourse-game—on students’ motivation, behavioral intention for heritage preservation, and scores. The second research question (RQ2) investigates the mechanisms linking motivation, behavioral intention for heritage preservation, and scores across these learning modes.

For RQ1, BMs demonstrate superior learning outcomes compared to single-modality approaches. The findings indicate that BMs achieve the highest learning effect, followed by digital games, and then online courses. This hierarchy aligns with prior research that has employed digital technology to innovate learning methods, leading to positive outcomes. For instance, students exhibit greater motivation when utilizing a guided tour system compared to traditional outdoor heritage learning48. In this study, digital games outperformed online courses, fostering stronger intrinsic motivation and leading to better academic performance. This advantage can be attributed to the design and interactive nature of digital games compared to online courses. By introducing BMs as a blended learning approach that combines asynchronous digital games with synchronous online courses, this study leverages the strengths of both modalities to create a more comprehensive and engaging learning environment for heritage education. Statistical analyses, including SEM and multi-group analysis, provide evidence that BMs outperform either digital games or online courses alone, suggesting that the combination of asynchronous and synchronous learning modalities can enhance student engagement and knowledge retention.

The sequence of learning significantly impacts educational outcomes. Parallel experiments revealed that the sequence of BMs—whether digital games precede online courses or vice versa—significantly impacts educational outcomes. BMgame-course is more effective for knowledge acquisition, aligning with a problem-oriented learning sequence that encourages students to generate questions through digital games and address them systematically via online courses. The asynchronous digital game experience offers students opportunities for independent exploration. This provides an active preview and reflection in the early stage for learning synchronous online courses by following teachers. In contrast, BMcourse-game enhances student satisfaction by establishing a knowledge foundation before gameplay, facilitating critical analysis and validation of learning in digital games. This insight provides educators with a strategic framework for optimizing heritage education programs. The findings align with Cuenca-López’s theoretical framework, which emphasizes a problem-oriented learning sequence36, and McCall’s argument that establishing a knowledge foundation before gameplay enhances students’ ability to critically analyze and validate their learning in digital games88.

Furthermore, the disparities in learning outcomes between the two groups can be analyzed through the integration of tangible and intangible elements of cultural heritage. Archeologists have emphasized the interdependence of tangible and intangible elements in various production processes, including those related to metal, stone, bone, and porcelain89. In porcelain production, factors such as materials, social traditions, and economic systems collectively shape a process that embodies both tangible and intangible heritage. Consequently, this study adopts an educational perspective that views intangible cultural heritage as being mediated through tangible elements, with the value of tangible cultural heritage being enriched by its intangible dimensions.

While online courses and digital games differ in format and focus, both aim to enhance students’ understanding of the connection between tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The online courses follow the traditional heritage education framework, focusing on tangible aspects. The instructor systematically explains the logic of porcelain production, site information, characteristics of unearthed porcelain artifacts, and their link to production techniques, all organized chronologically. In contrast, digital games highlight the intangible heritage of traditional porcelain-making craftsmanship. While guiding students through the porcelain-making process, the games introduce related sites and require students to engage within a virtually restored site environment.

Tangible cultural heritage consists of physical elements, while intangible heritage, such as craftsmanship and beliefs, reinforces abstract knowledge. The BMgame-course design reflects a pedagogical strategy of progressing from intangible to tangible elements. Research indicates that introducing concepts from abstract to concrete enhances cognitive skills90. Conversely, the BMcourse-game follows a concrete-to-abstract logic, aligning with traditional heritage education. It uses concrete representations to interpret abstract symbols, situating abstract concepts in real-world contexts91. This approach often yields higher student satisfaction due to its familiarity. Thus, the differing sequences of abstract and concrete elements may also account for the varying learning effectiveness observed in the two BM sequences.

For RQ2, the ARCS Model provides a robust theoretical foundation for heritage education. The ARCS Model (Attention, Relevance, Confidence, Satisfaction) was employed to evaluate learning motivation and its impact on behavioral intentions and learning outcomes. By integrating the ARCS Model into heritage education, the study uncovers the mechanisms linking motivation, satisfaction, and heritage preservation intentions. The findings confirm that motivational processing contributes to outcome processing, validating the ARCS Model in this context and offering a theoretical foundation for designing more effective heritage education curricula58,92. Specifically, attention, relevance, and confidence positively influence satisfaction in heritage learning, underscoring the importance of designing learning experiences that capture students’ attention and make the content relevant to their interests and prior knowledge. Furthermore, the non-invariance across the two BMs indicates that, although certain key pathways differ significantly, the overall mechanisms of the BMs in heritage education are largely consistent. This analysis helps identify both the stable and dynamic components of the ARCS model.

While this study has made significant contributions, it has the following three limitations. Firstly, this study primarily focuses on the constructs that explain the “Psychological Environment” related to motivation and learning, including attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction. Learning involves a complex set of mental and psychomotor activities related to the acquisition, retention, and recall of information and behaviors. The relationship between these constructs and other segments of the Motivation, Volition, and Performance (MVP) model is not well-defined in the context of heritage education. Therefore, future research should examine the influence of other segments, such as external inputs, volitions, and information processing, on behavioral intentions for heritage preservation. Additionally, exploring the competition mechanisms of the model under joint action, considering both positive and negative effects, is recommended. Secondly, the data for independent variables, mediating variables, and outcome variables in this study are derived from a single time point, which does not satisfy the temporal condition required for establishing causality. As a result, making a causal inference in a strictly theoretical sense is challenging. Future research should consider designing longitudinal studies with multiple time points and sources to better evaluate the mechanisms of BMs. Thirdly, this study discusses the mechanisms of learning primarily from the perspectives of different learning modes. Future research should further analyze the potential influence of other factors on these mechanisms, such as gender, grade, parental background, and subject.

In conclusion, this study employed two parallel groups to assess the learning effectiveness and mechanism of heritage education, yielding both theoretical and practical significance. The theoretical contributions are twofold. First, the study expands the understanding of heritage education theory by demonstrating that asynchronous digital games and synchronous online courses play distinct roles in different learning sequences. The BMgame-course aligns with the problem inquiry process, facilitating knowledge absorption, while the BMcourse-game enhances student satisfaction. Second, the study validates the theory of MVP and extends the ARCS model. It confirms that motivational processing contributes to outcome processing, which is applicable to heritage education. Moreover, satisfaction acts as a mediator between motivational processing and behavioral intention for heritage preservation. These findings lay a foundation for further research on motivation, learning outcomes, and the unique role of satisfaction in heritage education. In terms of practical value, BMs can be applied to heritage education in resource integration and sequence design. The findings highlight the potential of BMs to enhance learning outcomes, suggesting that the combination of asynchronous and synchronous learning modes can significantly boost student engagement and knowledge retention. BMs can be seamlessly integrated into formal education settings, facing challenges in visiting physical heritage sites, such as thematic courses, to enrich heritage education. Additionally, this approach can be applied to informal learning contexts, such as museums, to create engaging and effective learning experiences, either as a preview before visiting or as an element of flipped museums. In summary, this research not only introduces a novel learning approach but also provides valuable insights into the design and implementation of heritage education programs.

Data availability

Most data are included in the manuscript and the supplementary file. The raw, unprocessed data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Branchesi, L. Heritage education and its evaluation: field of research, methodology, results and forecasts. In Heritage education for Europe: outcome and perspective (ed Branchesi, L.) 29-58 (Armando Editore, 2007).

Fontal Merillas, O. & Ibáñez Etxeberría, A. La investigación en Educación Patrimonial. Evolución y estado actual a través del análisis de indicadores de alto impacto. Rev. Educ. 375, 184–214 (2017). “(in Spanish)” [Research on Heritage Education. Evolution and Current State Through Analysis of High Impact Indicators. Education magazine. 375, 184–214 (2017)].

Fontal, O., Arias, V. B. & Arias, B. A valid and reliable explanatory model of learning processes in heritage education. Herit. Sci. 12, 276 (2024).

Delgado-Algarra, E. J., & Cuenca-López, J. M. Challenges for the construction of identities with historical consciousness: Heritage education and citizenship education. In Handbook of Research on Citizenship and Heritage Education (eds Delgado-Algarra, E. J., & Cuenca-López, J. M.) 1–25 (IGI Global, 2020).

Barghi, R., Zakaria, Z., Hamzah, A. & Hashim, N. H. Heritage education in the primary school standard curriculum of Malaysia. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61, 124–131 (2017).

Chaparro-Sainz, Á & Rodríguez-Pérez, R. A. Perceptions on the use of heritage to teach history in Secondary Education teachers in training. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 7, 1–10 (2020).

Bian, X., Brown, A. & Marques, B. Heritage appreciation and awareness: a child educational approach exploiting animated video. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 44, 286–304 (2025).

Kastenholz, E. & Gronau, W. Enhancing competences for co-creating appealing and meaningful cultural heritage experiences in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 46, 1519–1544 (2022).

Levy, S. A. Heritage, history, and identity. Teach. Coll. Rec. 116, 1–34 (2014).

Cuenca-López, J. M., Martín-Cáceres, M. J. & Estepa-Giménez, J. Teacher training in heritage education: good practices for citizenship education. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 1–8 (2021).

Ott, M. & Pozzi, F. Towards a new era for cultural heritage education: discussing the role of ICT. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 1365–1371 (2011).

Tang, H., Zhang, C., & Li, Q. Assessing creativity and user experience in immersive virtual reality with cultural heritage learning. Int. J. Hum.Comput. Interact. 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2024.2405784 (2024).

Malegiannaki, I. & Daradoumis, Τ Analyzing the educational design, use and effect of spatial games for cultural heritage: a literature review. Comput. Educ. 108, 1–10 (2017).

Liritzis, I., Volonakis, P. & Vosinakis, S. 3 d reconstruction of cultural heritage sites as an educational approach. The sanctuary of Delphi. Appl. Sci.11, 3635 (2021).

Ye, L., Wang, R. & Zhao, J. Enhancing learning performance and motivation of cultural heritage using serious games. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 59, 287–317 (2021).

Adi Badiozaman, I. F., Segar, A. R. & Hii, J. A pilot evaluation of technology–enabled active learning through a hybrid augmented and virtual reality app. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 59, 586–596 (2022).

Paolanti, M., Puggioni, M., Frontoni, E., Giannandrea, L. & Pierdicca, R. Evaluating learning outcomes of virtual reality applications in education: a proposal for digital cultural heritage. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 16, 1–25 (2023).

Ye, L., Wang, R. & Hang, Y. The impact of puzzle-based game with scaffolding-aid on cultural heritage learning: evidence from eye movements. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 62, 323–356 (2024).

Koya, K. & Chowdhury, G. Cultural heritage information practices and iSchools education for achieving sustainable development. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 71, 696–710 (2020).

Mortara, M. et al. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 15, 318–325 (2014).

DaCosta, B. & Kinsell, C. Serious games in cultural heritage: a review of practices and considerations in the design of location-based games. Educ. Sci. 13, 47 (2022).

Alexander, J. W. Civilization and enlightenment: a study in computer gaming and history education. Middle Ground J. 6, 1–26 (2013).

Wainwright, A. M. Teaching historical theory through video games. Hist. Teach. 47, 579–612 (2014).

Jacobson, J., Handron, K. & Holden, L. Narrative and content combine in a learning game for virtual heritage. Distance Educ. 9, 7–26 (1995).

Matthys, M., De Cock, L., Vermaut, J., Van de Weghe, N. & De Maeyer, P. An “animated spatial time machine” in co-creation: reconstructing history using gamification integrated into 3D city modelling, 4D web and transmedia storytelling. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 10, 460 (2021).

Kidd, J. Gaming for affect: museum online games and the embrace of empathy. J. Curator. Stud. 4, 414–432 (2015).

Malegiannaki, I. A., Daradoumis, T. & Retalis, S. Teaching cultural heritage through a narrative-based game. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 13, 1–28 (2020).

Ennes, M. Museum-based distance learning programs: current practices and future research opportunities. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 22, 242–260 (2021).

Kraybill, A. Going the distance: online learning and the museum. J. Mus. Educ. 40, 97–101 (2015).

Pavlou, V. Museum education for pre-service teachers in an online environment: challenges and potentials. Int. J. Art. Des. Educ. 41, 257–267 (2022).

Mazzola, L. MOOCs and museums: not such strange bedfellows. J. Mus. Educ. 40, 159–170 (2015).

Harrell, M. H. & Kotecki, E. The flipped museum: leveraging technology to deepen learning. J. Mus. Educ. 40, 119–130 (2015).

McCall, J. Teaching history with digital historical games: an introduction to the field and best practices. Simul. Gaming 47, 517–542 (2016).

All, A., Castellar, E. N. P. & Van Looy, J. Digital game-based learning effectiveness assessment: reflections on study design. Comput. Educ. 167, 104160 (2021).

Martin, F., Sun, T., Turk, M. & Ritzhaupt, A. A meta-analysis on the effects of synchronous online learning on cognitive and affective educational outcomes. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 22, 205–242 (2021).

Cuenca-López, J. M. El patrimonio en la didáctica de las ciencias sociales: análisis de concepciones, dificultades y obstáculos para su integración en la enseñanza obligatoria 150–156 (Universidad de Huelva, 2010). “(in Spanish)” [Heritage in the Teaching of the Social Sciences: Analysis of Concepts, Difficulties and Obstacles to Their Integration into Compulsory Education 150–156 (University of huelva, 2010)].

McCall, J. Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History 76-109 (Routledge, 2022).

Martin, F., Kumar, S., Albert, D. & Ritzhaupt, D. Bichronous online learning: award-winning online instructor practices of blending asyn-chronous and synchronous online modalities. Internet High. Educ. 56, 1–12 (2023).

Martin, F., Polly, D., & Rithzaupt, A. D. Bichronous online learning: blending asynchronous and synchronous online learning. Educ. Rev. 8 (2020) https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/9/bichronous-online-learning-blending-asynchronous-and-synchronous-online-learning.

Martin, F., Kumar, S., Ritzhaupt, A. & Polly, D. Bichronous online learning: perspectives, best practices, benefits, and challenges from award-winning online instructors. Online Learn. 28, n2 (2024).

Aparicio, M., Oliveira, T., Bacao, F. & Painho, M. Gamification: a key determinant of massive open online course (MOOC) success. Inf. Manag. 56, 39–54 (2019).

Davis, D., Chen, G., Hauff, C. & Houben, G.-J. Activating learning at scale: a review of innovations in online learning strategies. Comput. Educ. 125, 327–344 (2018).

Mohammadi, G. Teachers’ CALL professional development in synchronous, asynchronous, and bichronous online learning through project-oriented tasks: developing CALL pedagogical knowledge. J. Comput. Educ. 11, 401–422 (2024).

Moreno-Murcia, J. A., Gimeno, E. C. C., Huéscar Hernández, E., Belan-do Pedreño, N. & Jesus Rodríguez Marín, J. Motivational profiles in physical education and their relation to the theory of planned behavior. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 12, 551–558 (2013).

Polet, J., Lintunen, T., Schneider, J. & Hagger, M. S. Predicting change in middle school students’ leisure-time physical activity participation: a prospective test of the trans-contextual model. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 50, 512–523 (2020).

Ruggiero, L., Seltzer, E. D., Dufelmeier, D., Montoya, M. G. & Chebli, P. Myplate picks: development and initial evaluation of feasibility, acceptability, and impact of an educational exergame to help promote healthy eating and physical activity in children. Games Health J. 9, 197–207 (2020).

Ma, L. & Lee, C. S. Evaluating the effectiveness of blended learning using the ARCS model. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 37, 1397–1408 (2021).

Chin, K.-Y., Lee, K.-F. & Chen, Y.-L. Effects of a ubiquitous guide-learning system on cultural heritage course students’ performance and motivation. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 13, 52–62 (2019).

Villena Taranilla, R., Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., González-Calero, J. A. & López Cirugeda, I. Strolling through a city of the Roman Empire: an analysis of the potential of virtual reality to teach history in Primary Education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 30, 608–618 (2022).

Palmgreen, P. Uses and gratifications: a theoretical perspective. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 8, 20–55 (1984).

Keller, J. M., & Suzuki, K. Use of the ARCS Motivation Model in courseware design. In Instructional Designs for Microcomputer Courseware (ed Jonassen, D. H.) 401–434 (Erlbaum, 1988).

Keller, J. M. An integrative theory of motivation, volition, and performance. Technol., Instr. Cognit. Learn. 6, 79–104 (2008).

Keller, J. M. Motivational Design for Learning and Performance 3–11(Springer-Verlag New York Inc, 2010).

Luo, J. M. & Ren, L. Qualitative analysis of residents’ generativity motivation and behaviour in heritage tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 124–130 (2020).

Corbishley, M. English heritage education: learning to learn from the past. In Education and Historic Environment (eds Corbishley, M., Henson, D., & Stone, P.) 67–73 (Routledge, 2004).

Cai, X. et al. Effects of ARCS model-based motivational teaching strategies in community nursing: a mixed-methods intervention study. Nurse Educ. Today 119, 105583 (2022).

Svec, L. Cultural heritage training in the US military. SpringerPlus 3, 1–10 (2014).

Huang, W.-H., Huang, W.-Y. & Tschopp, J. Sustaining iterative game playing processes in DGBL: the relationship between motivational processing and outcome processing. Comput. Educ. 55, 789–797 (2010).

Islamoglu, Ö, Üstün Demirkaya, F., Kurak Açıcı, F. & Aras, A. Cultural heritage education program for secondary school students. Croat. J. Educ. 24, 1289–1321 (2022).

Brislin, R. W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1, 185–216 (1970).

Keller, J. M. The MVP model: overview and application. N. Dir. Teach. Learn. 152, 13–26 (2017).

Tsai, P.-S. & Liao, H.-C. Students’ progressive behavioral learning patterns in using machine translation systems–a structural equation modeling analysis. System 101, 102594 (2021).

Martí-Parreño, J., Galbis-Córdova, A. & Miquel-Romero, M. J. Students’ attitude towards the use of educational video games to develop competencies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 81, 366–377 (2018).

Ucar, H. & Kumtepe, A. T. Effects of the ARCS-V-based motivational strategies on online learners’ academic performance, motivation, volition, and course interest. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 36, 335–349 (2020).

Zhang, J., Tong, Z., Ji, Z., Gong, Y. & Sun, Y. Effects of climate change knowledge on adolescents’ attitudes and willingness to participate in carbon neutrality education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 10655 (2022).

Cheng, T.-M., C. Wu, H. & Huang, L.-M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 21, 1166–1187 (2013).

Gursoy, D., Zhang, C. & Chi, O. H. Determinants of locals’ heritage resource protection and conservation responsibility behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 31, 2339–2357 (2019).

Ramkissoon, H., Smith, L. D. G. & Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: a structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 36, 552–566 (2013).

Wang, J., Wang, S., Wang, H., Zhang, Z. & Liao, F. Is there an incompatibility between personal motives and social capital in triggering pro-environmental behavioral intentions in urban parks? A perspective of motivation-behavior relations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 39, 100847 (2021).

Robillard, P. N. The role of knowledge in software development. Commun. ACM 42, 87–92 (1999).

Zack, M. H. Managing codified knowledge. Sloan Manag. Rev. 40, 45–58 (1999).

Castro-Calviño, L., Rodríguez-Medina, J. & López-Facal, R. Heritage education under evaluation: the usefulness, efficiency and effectiveness of heritage education programmes. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 7, 1–11 (2020).

Tan, S. K. & Tan, S. H. Clan/geographical association heritage as a place-based approach for nurturing the sense of place for locals at a World Heritage Site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 592–603 (2020).

Giménez, J. E., Ruiz, R. M. Á & Listán, M. F. Primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions about heritage and heritage education: a comparative analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 2095–2107 (2008).

Al Maani, D. & Mubaideen, S. Integration of cultural heritage in architecture: a national study of Jordanian higher education. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 30, 131–143 (2024).

Agrusti, F., Poce, A. & Re, M. Mooc design and heritage education. Developing soft and work-based skills in higher education students. J. E-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 13, 97–107 (2017).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling 7–15 (Guilford Publications, 2023).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 233–255 (2002).

Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P. & Hox, J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 9, 486–492 (2012).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Byrne B. M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming 271–289 (Routledge, 2016).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Bagozzi, R. P. & Yi, Y. On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs. J. Mark. Res. 26, 271–284 (1989).

Mackinnon, D. P. et al. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 7, 83–104 (2002).

Clogg, C. C., Petkova, E. & Haritou, A. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. Am. J. Sociol. 100, 1261–1293 (1995).

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P. & Piquero, A. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36, 859–866 (1998).

McCall, J. Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History 76–109 (Routledge, 2022).

Hodder, I. Entangled: A New Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things 95–112 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2023).

Zeng, J., Zhang, P., Zhou, J., Shang, J., & Black, J. B. The impact of embodied scaffolding sequences on STEM conceptual learning. ETR&D-Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 1–26 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10438-x (2024).

Fyfe, E. R., McNeil, N. M., Son, J. Y. & Goldstone, R. L. Concreteness fading in mathematics and science instruction: a systematic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 26, 9–25 (2014).

Keller, J. M. An integrative theory of motivation, volition, and performance. Technol. Instr. Cognit. Learn. 6, 79–104 (2008).

Hair, J. F. et al. Multivariate Data Analysis 111–122 (Prentice Hall, 2009).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Yi Liu and Jingwen Zhang (Professors, College of History, Nankai University) for useful discussions. This study was partly supported by Tianjin Research Innovation Project for Postgraduate Students (grant number 2022BKY051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. conceived and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, prepared all figures, wrote the manuscript, and revised it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, M. Bichronous modes in heritage education for enhancing motivation and learning outcomes via the ARCS model. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01858-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01858-w