Abstract

Reworking paintings has been a common practice throughout art history, with artists modifying their own work at various stages and occasionally altering pieces by others. Advances in chemical imaging and increased access to traditional imaging techniques have facilitated the documentation of such interventions. Initially focused on Old Masters, research on reworking practices has expanded to nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists. For the first time, a classification system for reworkings is introduced, based on the oeuvre of Belgian Modernist painter James Ensor (1860–1949). Five representative case studies each illustrate one of the proposed types of reworking: (1) pentimenti, (2) post-factum revisions, (3) recycled works, (4) metamorphoses, and (5) appropriations. Using advanced imaging and spectroscopic techniques, including Macro X-Ray Fluorescence (MA-XRF) and instrumentation from the Iperion HS consortium, the study also provides material-technical evidence of Ensor’s experimental studio practice while shedding new light on anachronisms in his oeuvre.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reworking of paintings has been abundantly reported in art history. Artists have frequently made adaptations to the works of older masters1, with some of the most notable examples being the “Rubenisato” (or “Rubenized”) pieces, a term referring to P.P. Rubens’s (1577–1640) practice of touching up the original or copied drawings and paintings by fellow artists. For this seventeenth-century Flemish master, reworking is especially associated with repair work, (self-)training purposes, and building a corpus of models for inspiration or future reference. Nevertheless, Rubens is also known to have gone beyond applying contours and washes, and changing the subject of a painting, for instance, when he changed a hermit in a landscape by Paul Bril (1554–1626) into Psyche (Landscape with Psyche and Jupiter, ca. 1610, Museo Del Prado)2. Next to Rubens, many other artists have touched up works by predecessors, mostly in the framework of conservation treatments, such as the large-scale, sixteenth-century overpaints documented on the Ghent Altarpiece by Van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441)3. In some cases, these early restorers were forced to cover up damage or the impact of physical interventions on the support. An example of the latter is the replacement of wooden boards of panel paintings that were affected by injurious insects or that were adapted to fit a new frame or architectural setting, as recently discussed by De Leu et al.4. Moreover, artists frequently intervened on their own works, making adjustments and modifications during all possible stages of the creative process. Notable examples are the so-called Anstückungen to panels4,5, pentimenti between the underdrawing and painting stage6, in the composition7, or the recycling of entire works8,9.

For a long time, the applicable diagnostic techniques to trace and document these reworking practices remained limited to X-ray radiography (XRR), infrared photography (IRP) and reflectography (IRR), but technical innovations in chemical imaging in the last two decades have equipped heritage scientists with more advanced tools, in this way reviving the attention for reworked paintings3,4. As such, not only were artworks revisited that had been known to be adjusted, resulting in entirely new or more accurate insights10,11, but also periods that had remained understudied received more attention. For instance, the interest in nineteenth-century reworking was intensified by the visualization of a woman’s head, hidden under Van Gogh’s (1853–1890) Patch of Grass, by Dik et al. in 2008, at the same time introducing Macro X-ray Fluorescence (MA-XRF) as a new and promising “third” imaging method, next to XRR and IRR12.

Hidden compositions have been reported in paintings by Modernist artists such as Edgar Degas (1834–1917)13, René Magritte14 (1898–1967), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) as well. Picasso not only completely overpainted certain of his works, but also reworked parts of his compositions at a later point in time, altering the painting significantly15. This was also seen on paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919)16 and Emil Nolde (1867–1956), the latter altering the dark color scheme to a lighter and more colorful scheme, rather than altering the composition. Nolde’s body of work also demonstrates other forms of reworking, such as cutting paintings into separate parts and modifying the format of the pieces through cropping or resizing17. However, to date, these accounts on reworkings remain fragmentary and case-based, while the continuous reports of reworked paintings call for a broader contextualization, especially within the changing studio practice of Modernist painters. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, painting techniques changed rapidly as artists sought innovation and successfully attempted to break free from the longstanding academic conventions18. Rapid changes in material use and paint handling can be exploited as markers by heritage scientists today, aiding them to detect stylistic, iconographic and material-technical anachronisms in the oeuvre of specific artists19. In the context of this study, a material-technical anachronism refers to the use of materials, techniques and styles in a painting that were not available or employed by the artist at the time the work was supposedly created. Their presence suggests later intervention by the artist (or others).

The urge to innovate and experiment during the nineteenth century caused some artists to rework their own (or other artists’) works, as was the case for the Belgian Modernist painter James Ensor (1860–1949), most famous for his depictions of grotesque figures, masks, and skulls. His body of work is typically divided into three stylistic periods: (1) an early realist period (1873–1885), noted for its somber and subdued color palette, (2) a second period (1885–1900) characterized by grotesque figures, masks and skeletons, rendered in bright and vivid colors, and (3) a late period (1900–1949) distinguished by light hues, applied in thin, pure and sometimes translucent layers20. He created around 850 paintings in 65 years. Ensor is seen as the founding father of Belgian Modernism and a predecessor of twentieth-century Expressionism, as well as a prominent figure within Europe’s Symbolist movement21. In spite of their impact, his works are less known to the international public due to the excessive diversity of his work. An important part of his oeuvre was rapidly acquired by Belgian museums. Nevertheless a few of his key works are on permanent display in important museum galleries such as The Museum of Modern Art in New York (US), The Art Institute of Chicago (US), the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles (US), the Neue Pinakothek in Munich (DE), The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (CA) and the Menard Art Museum in Nagoya (JP).

Throughout the years, many critics and art historians have interpreted Ensor’s artworks, but it was art historian Paul Haesaerts22 (1901–1974) and later Marcel De Maeyer (1920–2018) who were the first to notice stylistic, iconographic, and material-technical anachronisms in Ensor’s drawings23 and paintings19. De Maeyer pointed out several drawings and ca. 14 paintings that were reworked by Ensor long after their initial completion. Ensor created these works during his early realistic period, characterized by a dark painting palette. On stylistic and iconographic grounds, as well as raking light and IRP, De Maeyer concluded that Ensor reworked these compositions after 1886 by adding colorful, grotesque elements characteristic of his later period19, thereby blending realism and irrealism in a way previously unseen in Western art history23. In 2013, the Ensor Research Project (ERP) was founded by the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), aiming to investigate Ensor’s life and work. For this project, many of his paintings were systematically documented using Ultraviolet Induced Visual Fluorescence Photography (UIVFP), IRP, IRR, Infrared False Color, raking light, XRR, and, where possible, MA-XRF. This provided more detailed insights into Ensor’s reworking practices than previously possible. As part of the ERP, over 80 paintings were radiographed, revealing small pentimenti and numerous cases of complete overpaints. The overpainted compositions are varied in iconography, ranging from still lifes—such as Ensor at His Easel (1886?, KMSKA)—to underlying portraits in works like Still Life with Oysters (1882, KMSKA). They also include academic figure studies (Still Life with Chinoiseries, 1880, KMSKA)24, religious scenes (Still Life with Cloth, 1880, Mu.ZEE, Ostend, BE), and compositions with forms too ambiguous to identify. Art historian Herwig Todts (b. 1958) broadened and developed the hypothesis regarding reworking practices in Ensor’s oeuvre, categorizing his interventions into four distinct types, thereby building on the discoveries of Haesaerts, De Maeyer, the ERP, and his own observations25.

The first four types outlined in this manuscript align with Todt’s original observations, while his classification has been expanded and refined with the support of material-technical evidence. The research led to the identification of a fifth category, resulting in the following five types of changes found in Ensor’s oeuvre: (a) pentimenti: the application of changes throughout the painting process; (b) post-factum revisions: minor changes on the already dry paint of completed works that do not fundamentally change the meaning of the image; (c) metamorphoses: modifications on the finished painting that fundamentally change the meaning of the painting—from a physical point of view, these interventions can be either extensive or minute; (d) recycling: the original composition is completely obscured and overpainted, with the initial work reduced to a mere, albeit fully prepared, substrate for a new composition; and (e) appropriation: modifying artworks by other artists, to create a new piece, claimed by the appropriating artist as its own. To exemplify these five types, five case studies from Ensor’s oeuvre are discussed in more detail in the next paragraphs. The fifth category, appropriation, represents a novel addition to Todt’s observations, introduced by the authors. This expanded framework offers a more thorough understanding of the range and nature of alterations observed in Ensor’s artworks. This research is part of a comprehensive study of his body of work performed within the larger framework of the ERP, and in the context of the 2024 Ensor tribute year in Belgium (Ensor.2024|Toerisme.Vlaanderen).

Methods

Case studies

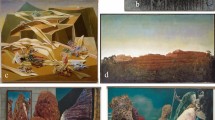

To illustrate the proposed types of reworking in James Ensor’s paintings, five representative case studies were selected (Fig. 1). Based on prior visual and technical analysis (IRP, IRR, XRR), each painting clearly exemplifies one category through both visual and material evidence. Case Study 1: The Skeleton Painter. Painted in 1896, this work belongs to Ensor’s second artistic period. Executed in oil on panel and measuring 37.3 × 45.3 cm, it is part of the KMSKA collection (inv. no. 3112). The painting serves as a representative example of the first category of reworking: pentimenti—changes made during the painting process. Moreover, the case reflects broader practices in Modernist art, where photography was used as a compositional aid without constraining artistic interpretation. Case Study 2: Woman with Upturned Nose. Painted in 1879, this work belongs to Ensor’s first artistic period, characterized by a realistic and dark style. It is part of the KMSKA collection (inv. no. 2077) and was executed in oil and colored pencil on canvas, later marouflaged onto panel during a restoration treatment. Measuring 53 × 43.5 cm, the portrait exemplifies post-factum revisions. The painting was also examined during a MOLAB access (IPERION HS). Case Study 3: The Bourgeois Salon. Painted in 1881, this early realistic work by Ensor is part of the KMSKA collection (inv. no. 2735). It is executed in oil on canvas and measures 132 × 108 cm. The composition depicts two women knitting in a bourgeois living room. This painting exemplifies the category of recycled works, in which a previously finished composition is repurposed as a support for a new painting. Case Study 4: Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat. Dated 1883 and reworked in 1888, this self-portrait by Ensor is part of the Mu.ZEE collection (inv. no. SM000157). Executed in oil on canvas, it measures 76.5 × 61.5 cm. The work exemplifies Ensor’s practice of metamorphosis, where a previously finished painting was reworked years later to radically alter its meaning. Case study 5, The Adoration of the Shepherds. Painted in 1887, this work is part of the KMSKB collection (inv. no. 7626). Executed in oil on panel, it measures 46.7 × 60 cm. The painting exemplifies the category of appropriation, in which Ensor appropriated and reworked a nineteenth-century peasant scene by an unknown artist, transforming it into a religious composition.

a The Skeleton Painter, 1896, KMSKA. Courtesy of Rik Klein Gotink, KMSKA. b Woman with Upturned Nose, 1879, KMSKA. Courtesy of Adri Verburg, KMSKA. c The Bourgeois Salon, 1881, KMSKA. Courtesy of Rik Klein Gotink, KMSKA. d Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat, 1883–1888, Mu.ZEE. Courtesy of Adri Verburg, KMSKA. e The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1887, KMSKB. Photograph by R. Klein Gotink for the Ensor Research Project (KMSKA, 2013–present).

VIS/UV/IR Photography and X-ray radiography

All paintings were documented using Visible Light Photography (VIS), raking light, UIVFP, IRP (IRR for case study 5), and XRR in combination with a visual examination of the paint layer. VIS images by photographer Rik Klein Gotink (freelancer, The Netherlands) were made with a Hasselblad (Göteborg, Sweden) H5D-50c or H6D-100c camera with 2 Broncolor (Allschwil, Switzerland) studio flashes, each equipped with softboxes. All paintings were photographed in raking light from the left, using a single Broncolor flash unit with an open reflector. The IRP images were made with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II or Canon 5Ds camera (Canon Inc., Ota, Japan), which were both modified to capture infrared radiation. The Jenoptik (Jena, Germany) UV-VIS-IR 60 mm 1:4 APO Macro lens was used with an 850 nm IR filter, and a setup was created using two Broncolor studio flash units, each equipped with a softbox, positioned at a 30° angle to the painting. All shots were made with a resolution of 600 ppi in tiling and were stitched. VIS, UIVFP, IRR, and XRR were made by Adri Verburg (VZW Arcobaleno, The Netherlands). The XRR images were made with a MOBILIX HF2 adjustable from 40 to 100 kV with a maximum of 20 mA current. The XRR image of case study 3 has been processed with the Platypus software (https://bigdata.duke.edu/projects/platypus/) to digitally remove the wooden stretcher of the painting in the image.

3D microscope

Digital 3D microscopes (Hirox Europe, Limonest, France) from the ARCHES research group at the University of Antwerp (UAntwerpen) and KMSKA were used to make high-resolution images and scans of the paint layers of case studies 2 and 4. Both systems are placed on an X-Y-Z software-controlled motor stage with a travel range of 50 × 50 cm and 8 cm on the Z-axis. A telecentric Ultra-High-Resolution Motorized Zoom Lens (HR-1020E) with ×30 and ×90 magnification and an AC-1020P polarizing filter was in place. The paintings were examined using a diffuse visible LED ring light, raking light positioned at a 45° angle from the upper right corner, and UV light. The obtained images were stitched using PTGui.

MA-XRF imaging

All paintings were scanned with the in-house built AXIL scanner of the AXIS research group of the UAntwerpen, using a 50 W XOS tube (East Greenbush, NY) with Rh anode operated at 50 kV and 1 mA, focusing the primary beam with a polycapillary lens to a spot size of 200 µm. A Vortex EX-90 SDD detector (Hitachi High-Tech America, Inc., California, US) was employed to detect the secondary fluorescence signals. The system was mounted on an X-Y motor stage that is software-controlled, which makes it possible to sweep over the painting surface in serpentine mode. Careful positioning allowed for a quasi-constant distance of 2 cm between the lens tip and the paint surface. The maximum travel range of the scanner is 57 × 60 cm (h × v).

Case study 1, The Skeleton Painter, was scanned covering an area of 34 × 47 cm, leaving unscanned strips of ~2 cm at the top and bottom. It was performed with a step size of 500 µm and a dwell time of 320 ms per pixel. Case study 2, Woman with upturned Nose, was fully scanned with a scan size of 39 × 51 cm, using a step size of 650 µm and a dwell time per pixel of 150 ms. For Case Study 3, The Bourgeois Salon, the edges of the painting were left unscanned due to its size and time constraints. The scan in the upper-left quadrant measured 60 × 55 cm with a dwell time of 90 ms per pixel, while the upper right quadrant scan measured 60 × 57 cm with a dwell time of 100 ms. Similarly, the lower left quadrant scan measured 56.5 × 55 cm with a dwell time of 100 ms, and the lower right quadrant scan measured 57 × 59.5 cm with a dwell time of 110 ms. All four scans were conducted with a step size of 650 µm. Two scans were made on case study 4, Self-portrait with Flowered Hat, each scan measuring 57 × 40 cm with a dwell time of 130 ms and a step size of 600 µm. This used the full range of the X-axis, which was not wide enough to cover the complete width of the painting, therefore leaving strips of ~2 cm unscanned on both sides of the painting. Case study 5, (The Adoration of the Shepherds), was almost fully scanned with one MA-XRF scan. The scan measured 43 × 57 cm with a step size of 650 µm and a dwell time per pixel of 150 ms. The maximum scan range was used on the X-axis, leaving strips of 1.5 cm unscanned on both sides of the painting. All data was processed using data analysis software Datamuncher Gamma 1.4 version26 and Python Multichannel Analyzer (PyMca)27.

BelMod project by MOLAB Iperion HS

In 2022, several research techniques were performed on three paintings by James Ensor at KMSKA, accessing the MOLAB infrastructure within the IPERION HS consortium as part of the research project BelMod28. A selection of the results obtained on Woman with Upturned Nose are integrated in this paper, in particular the results from (a) Hybrid Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and microscopic reflectance spectral imaging developed and performed by ISAAC lab from Nottingham Trent University; (b) Low Energy X-Ray Fluorescence (LE-XRF) performed by XRAYlab from Instituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale of Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (ISPC CNR) in Catania; and (c) UV-VIS Reflectance, UV-VIS induced fluorescence Hyperspectral Imaging (450–1000 nm), and Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) from SMAArt Centre of Excellence of University of Perugia & Istituto di scienze e tecnologie chimiche “Giulio Natta” (SCITEC) of CNR.

-

(a)

The hybrid OCT and spectral imaging system consists of a Fourier Domain OCT centered at 1250 nm in wavelength and coaligned with a filtered illumination-based reflectance spectral imaging system in the visible-near infrared (425–845 nm). This produced 5 × 5 × 1.5 mm (Width × Length × Depth) OCT volumetric data sets at a transverse resolution of 10 µm and depth resolution of 8 µm in varnish and paint (assume refractive index = 1.5) and spectral images with transverse resolution of 5 µm and spectral resolution of 10 nm. Color images were derived from the microscopic reflectance spectral images, assuming a CIE standard 2° observer and D65 illuminant.

-

(b)

The LE-XRF system is a compact and portable spectrometer designed and developed at the XRAYLab of ISPC CNR in Catania. It features a 100 W tungsten anode X-ray source positioned orthogonally to the sample surface. A lead collimator at the beam’s exit ensures a 5 mm beam diameter at a 1 cm distance. The X-ray tube operates at low voltage (8 kV) and high current (2 mA), providing an analytical depth of a few microns for dense materials like metals and up to 20 microns for lighter materials such as ceramics or glass. The low-energy source results in reduced spectral noise, enhancing the detection of light elements. Fluorescence signals are detected by an SDD detector with an 80 mm² active area and an energy resolution of 140 eV at 5.9 keV. Positioned above the source at a 45° inclination relative to the sample surface, the detector is equipped with an 8 µm mylar-sealed cap that enables detection in a helium atmosphere. A continuous helium flow is maintained during measurements to minimize air absorption, improving the detection of light elements (Z ≥ Na). Elements from sodium (Na) to zinc (Zn) are efficiently detected through their K-lines, while heavier elements (e.g., Au, Hg, Pb) are identified via their M-lines. The system’s detection limits range from 10 to 100 ppm, depending on the matrix material, allowing for the analysis of both major and trace elements. Typical measurement times are around 100 s to ensure sufficient statistical accuracy.

-

(c)

A SOC710 produced by Surface Optics Corporation (San Diego, USA) has been used for hyperspectral measurements. The system utilizes a whiskbroom line scanner producing a 696 × 520 pixels hypercube in the 400–1000 nm spectral range with 128 bands and about 4.5 nm spectral resolution. The spatial resolution can be continuously modulated by the adjustable focal length of the mounted objective. Two Elinchrom Scanlite 350 W Halogen lamps (Elinchrom, New York, US) with diffusing umbrellas have been used for reflectance measurements, while two Honle Ledline 500 LED systems (Gilching, Germany) emitting at 405 nm have been used for luminescence measurements. Reflectance, fluorescence, and TCSPC point measurements have been performed with a prototype instrument assembled at the SMAArt Centre29.

Literary and archival study

Literature and archival research was conducted to contextualize the findings within the broader framework of art history and heritage science. The majority of sources consulted consisted of published literature, including art-historical and material-technical monographs on specific artists, catalogs raisonnés, journal articles, and artist biographies. Archival materials—such as letters, conservation reports, and documentation related to the case studies—were consulted in several Belgian institutions, including the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (KMSKB), KMSKA, and Mu.ZEE in an effort to reconstruct James Ensor’s possible motivations. The KMSKA’s Online Scholarly Catalogue (https://kmska.be/en/osc/online-scholarly-catalogue) of Ensor’s work was also consulted to identify additional examples for specific categories of intervention. Efforts were made to prioritize recent, peer-reviewed publications in English. However, due to Ensor’s prominence in Belgium, many key sources were in Dutch. Where available, English translations of these publications were cited. Where possible, information on Ensor’s working methods was compared to the studio practices of his contemporaries, in order to situate his approach within a broader Modernist context and to highlight contrasts with the techniques of the Old Masters. All references were managed using Zotero (https://www.zotero.org/).

Large Language Model (LLM)

To optimize the presentation of the research findings, LLMs (ChatGPT and Gemini) were used as a linguistic tool to improve the grammar and overall readability and coherence of the manuscript. These LLMs were not used to gain new insights or research results.

Results

Type 1: Pentimenti—The Skeleton Painter

As noted in the introduction, five distinct types of reworking have been identified in Ensor’s paintings. The first type concerns the well-known pentimenti— corrections made during the painting process—which is exemplified by The Skeleton Painter from 1896. As shown in Fig. 2a, the IRP of The Skeleton Painter features a full carbon-based underdrawing made with pencil. The painting, showing the artist at work, is based on a photograph that was taken by an unknown photographer in Ensor’s studio in 1896, the same year the painting was made (Fig. 2b). The underdrawing does not replicate the proportions of the photograph accurately, as the depicted studio space was enlarged and the perspective modified. Most probably, Ensor copied most of the contours from the photograph onto the prepared panel in freehand, instead of employing a transfer technique.

a IRP of the painting. Courtesy of Rik Klein Gotink, KMSKA. b Historical photo showing James Ensor in his studio in the corner house of Vlaanderenstraat and Van Iseghemlaan in Ostend. 1896, Mu.ZEE Ostend, artinflanders.be, unknown photographer, artinflanders.be. c Detail of the MA-XRF distribution image of the element mercury (Hg-L). d Composite image of the Hg-L image in red, superimposed on the corresponding IRP area. e Composite image showing the Hg-L image in red, superimposed on the corresponding RGB image. The yellow arrows indicate the shortened leg of the chair, which has slightly changed position.

Ensor frequently used photographs as a reference for his paintings, and he was acutely aware of the controversies surrounding the use of photography in art. This was exemplified by his parody of L’Appel de la Sirène (ca. 1891), a composition referencing the controversy surrounding Jan Van Beers’s La Sirène. Van Beers had been accused of painting over photographs or basing his work on photographic images, leading to the creation of hyperrealistic paintings30. In The Skeleton Painter, Ensor utilized the photograph merely as a foundational reference for his composition, incorporating several artistic modifications distinct from the original image and not as an aid to achieve hyperrealism. The changes include intentional modifications in color, detail, and composition, resulting in a depiction that diverges from reality. In particular, the left edge of the photograph was not included in the drawing, while content-wise, skulls were added at the bottom left and top left corner, a hat and a seashell were placed on the floor, and paintings on the wall were modified. Finally, Ensor deviated from the photograph by depicting a standing skeleton, instead of himself in a sitting position, with one leg slightly raised and a foot resting on a leg of the easel.

Ensor followed the underdrawing closely while painting, each color area placed next to the other with minimal overlap. Nevertheless, small differences between the underdrawing and the paint layer are present and are here interpreted as pentimenti. The Italian word pentimento literally means “remorse” and is traditionally defined as a correction made by the artist during various stages of the painting process31. These corrections can be applied when the artist proceeds from the sketching (or transfer) phase to the actual painting phase, but also during the painting phase itself. An example of the first can be seen in Fig. SI-1f, g, where the top of the chair behind the skeleton figure was painted lower than the position indicated in the drawing. An example of the second case is observed near the signature at the bottom right, where Ensor initially painted a red area, which he covered with white paint. The underlying red layer was probably not completely dry at that time, resulting in a network of drying cracks (Fig. SI-1e). However, the most intriguing pentimento is found in the skeleton painter itself. The underdrawing in the IRP reveals how Ensor first drew his own face using a dry carbonaceous material, while a skull is visible at the paint surface. The IRP shows no indications of a skull in the underdrawing. However, under the magnification of a stereomicroscope, a painted sketch in red paint strokes contouring the standing figure becomes visible below the surface paint. MA-XRF visualized this underlying sketch accurately, as the red contours show up in the mercury map (Hg-L). Figure 2c, d demonstrates how these lines are present underneath the skull and the blue suit of the figure. The fact that the mercury distribution reveals details of the physiognomy of the skull, such as the outline of the teeth, jawline, and cheekbone, informs us about the exact moment Ensor abandoned the idea of the self-portrait, i.e., in the ébauche phase (i.e., the earliest lay-in of paint).

In addition, the MA-XRF mercury (Hg-L) map, ascribable to red vermilion, also reveals how the depicted figure was first shown in a sitting position, as in the photograph, and not standing next to the easel, as we can see it today in the painting. In particular, the Hg-L map exhibits, albeit faintly, the contours of this seated, overpainted figure. The informed beholder can visually see a pointed shoe shimmering through the upper paint layer, resting on the lower bar of the easel, closely matching its position in the photograph (see Fig. SI-1a, b). The zinc map displays the shape of this bent leg “in negative.” The outlines in this image are caused by the radio-opaque vermillion and/or cobalt blue paint strokes, blocking the zinc (Zn-K) signals stemming from below (see Fig. SI-1h, i). Zinc is present as a uniform layer that extends over the entire surface of the painting, presumably coming from a zinc white-containing double ground. While canvasses were commercially prepared with zinc white from the late nineteenth century onwards32, it cannot be excluded that the zinc white layer was applied by Ensor, as some other instances of the use of zinc (e.g., Still life with Chinoiseries, 1906) or lead white layers (e.g., The Temptation of Saint Anthony the Great, 1927) by Ensor have been encountered. In this way, the zinc distribution presents us with a shadow image, hence “negative,” of the superimposed cobalt and/or vermilion paint.

A close comparison reveals that the seated Ensor in the photograph exposes different parts of the chair than the standing skeleton in the painting. Notably, one can discern how the brown edge of the chair’s seat extends beneath the blue suit of the standing figure (i.e., below the rim of the paint palette, see Fig. 2e). In addition, the mercury map (yellow arrow in Fig. 2c) demonstrates how one of the chair’s legs was shortened and moved back to adjust the perspective, when the figure was changed to a standing position. In summary, for this specific case, we can discern pentimenti in two separate phases of the creative process. The aforementioned transition from self-portrait to skull occurred when the pencil sketching phase was abandoned and the first paint was laid in, whereas the shift from sitting to standing was made after the first paint lay-in was completed and the artist proceeded to the final painting stage. The latter was substantiated by technical photography as the raking light image reveals the contours of Ensor’s right leg resting on the easel. In this way, the topography implies that the sitting figure was already executed in paint, while a pencil sketch of this position is not clearly recognizable.

Type 2: Post-factum revisions—Woman with Upturned Nose

In contrast to pentimenti, post-factum revisions are generally more difficult to verify and therefore less frequently discussed in the literature. In this study, post-factum revisions refer to later changes made by the artist on works that were previously considered finished. Some paintings by nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists remained in their studios for extended periods, sometimes throughout their entire lives. This gave artists ample opportunity to revisit and alter their works after completion. These alterations are often only detectable when enough time has elapsed between the painting’s initial completion and the reworking for an evolution in studio practice to occur. Differences in the materials employed and/or painting technique provide key reference points for identifying these subtle revisions. In Ensor’s work, evidence of post-factum revisions is present, though these adjustments are often subtle and difficult to unequivocally certify as such. One subtle example of a revision was observed in the portrait Woman with Upturned Nose (1879, KMSKA collection). The eyes, lips, and earrings of the sitter exhibit a distinct pinkish fluorescence in UIVFP images, characteristic of a red lake pigment (Fig. 3UIVFP, 3b, d).

From left to right and top to bottom: UIVFP image of Woman with Upturned Nose (1879, KMSKA), courtesy of A. Verburg, KMSKA. a Detail of the mouth under visible light. b Detail of the mouth under UV light showing a pink fluorescence from a red lake pigment. The same fluorescence is present in the earrings as well (details c, d). e Detail of Woman with Upturned nose showing an area where yellow and blue colored pencil has been used, a technique typical of Ensor’s later period. f Composite Vis hyperspectral distribution map and corresponding reflectance spectra of: red lake (magenta); vermilion (orange); Thenard blue (blue); lead white (black). g Red Lake distribution map and relative luminescence spectrum.

These distinctive thin and short paint strokes are considered to be later additions, not only because they appear to be applied on top of a dry paint layer, but especially because this red lake, intensively fluorescing under UV light, is typically associated with Ensor’s later stylistic periods (ca. 1887–1949)20. Based on the investigation of ~120 UIVFP images, the characteristic salmon-pink fluorescence stands out clearly in images of many of Ensor’s works from around 1888 onwards (see, e.g., Fig. SI-2a, b). This fluorescence, however, appears absent in his early works (ca. 1873–1885) to which Woman with Upturned Nose belongs. In situ LE-XRF analysis, conducted during the Molab campaign, established a significant aluminum (Al) content in these red lake patches, whereas further investigation with UV-VIS Reflectance, UV-VIS induced fluorescence Hyperspectral Imaging (450–1000 nm), and TCSPC identified madder lake in the lips and the earrings of the woman in the painting (Fig. 3f, g) together with Thenard Blue, vermilion, and lead white. These findings suggest that the fluorescent paint is composed of madder lake with an aluminum substrate. The Hybrid OCT measurements show that the red glaze layer (translucent red paint) is located beneath the varnish layer, not on top, as there appears to be continuity in the top layer between regions with and without red glaze, likely indicating that the top layer corresponds to the varnish and the glaze is present underneath (Fig. 4a–c). If the red glaze were found on top of the varnish, it would provide stronger support for the hypothesis of later reworking. In addition to the madder lake paint, Woman with Upturned Nose was also reworked with dry materials, i.e., yellow and blue pencil; this is again a technique that is typically associated with Ensor’s later style (Fig. 3e). Notable examples where Ensor combines colored pencil with paint are The Temptation of Saint Anthony the Great (see Fig. SI-3), Carnaval in Binche (1924, KMSKA, long-term loan Rubey), and Danse dans la clairière (1913, Phoebus Foundation). The presence of the combination of these blue and yellow lines in a dry medium with the aforementioned red fluorescent lake, both applied on the already dry paint, strengthens the belief that Woman with Upturned Nose was post-factum revised by Ensor himself. As indicated in Fig. 4, a few discrete, red paint strokes emerge distinctively in the barium (Ba-L), cobalt (Co-K), and tin (Sn-L) MA-XRF images. These might be part of the revision as well, but could not be unambiguously classified as such. Another notable form of post-factum revision frequently observed in Ensor’s oeuvre is the inclusion of multiple signatures within a single painting.

Top row: VIS image of Women with Upturned Nose, courtesy of A. Verburg, KMSKA. The red square indicates the MA-XRF scan area with the resulting barium (Ba-L), cobalt (Co-K), and tin (Sn-L) elemental maps shown on the right. The barium, cobalt, and tin paint strokes appear to be added on a dry paint layer and might be part of the post-factum revision. The yellow square indicates the area of a high-resolution MA-XRF scan results of which are shown in the middle row. Middle row: detail of the UIVFP image, courtesy of A. Verburg, KMSKA. The white arrow indicates a small paint stroke, fluorescing in pink. To the right: detail of the eye in visible light, followed by a composite MA-XRF image of the eye showing Ba-L (red), Co-K (blue), and Sn-L (green) signals. The corresponding paint strokes appear to be added on a dry paint layer. a OCT virtual cross-section showing a region of varnish and red glaze over red paint around the lips. The glaze is confined to the far left of the cross-section. The vertical scalebar corresponds to a depth of 250 µm in air. b Color image derived from the microscopic reflectance spectral image assuming CIE standard 2° observer and D65 illuminant, with cross sections shown in (a, c) marked. c The thickness of the two transparent layers is 11.2 µm and 18.7 µm, assuming a refractive index of 1.5. Multiple layers can only be seen over regions of red glaze.

Type 3: Recycled works—The Bourgeois Salon

One of the largest paintings in Ensor’s oeuvre, painted on top of another composition, is The Bourgeois Salon, a realistic work from Ensor’s early period. It depicts the living room of his parental home, showing two women knitting at a table. When the XRR is rotated 90° counterclockwise (Fig. 5b), a bearded figure wearing a hat is revealed in the upper-left quadrant of the image (see Fig. 5, detail 1). The figure’s cape is also visible in the IRP, and even more distinctly in the infrared false-color image (see Fig. SI-5). Additional details emerge in the MA-XRF images, enabling a partial reconstruction of the underlying scene, which might depict a biblical theme. The elemental distribution maps for mercury (Hg-L), iron (Fe-K), and manganese (Mn-K) (Fig. 5c–e) reveal the stance and attire of the bearded figure and a second person, kneeling at his side. The bearded figure is depicted standing barefoot, with legs parted, his left arm raised to hold a staff, and his right arm extending downward toward an object resembling an apple (or an imperial orb?). A kneeling second figure, visible in the map of mercury, seems to be offering the object to the bearded man. The kneeling figure appears to be a woman, dressed in a long gown. Unfortunately, her face remains obscured in all MA-XRF maps, as a thick Pb-based layer (likely ascribable to lead white) from the superimposed The Bourgeois Salon covers that area. However, the woman’s face is discernible in the XRR, though it was initially overlooked because the middle bars of the wooden stretcher cross over this part of the image. By digitally removing the wooden stretcher using the Platypus software, her features became more clearly visible (Fig. 5, detail 2). The background of the biblical scene also became more discernible, revealing what appears to be a landscape with rocks and vegetation on the right side and a small glimpse of the sky, though the shapes remain challenging to identify with certainty.

a Visible light photograph (VIS) of The Bourgeois Salon (1881, KMSKA), rotated −90°. Courtesy of Rik Klein Gotink, KMSKA. The yellow rectangle indicates the MA-XRF area for which the corresponding elemental maps are shown below. A virtual reconstruction of a part of the underlying composition was made based on XRR, IRP, and MA-XRF and plotted in white lines on the RGB image. A standing figure with a beard, hat, cape, and staff emerged from the combined imagery, receiving what appears to be an apple from a kneeling figure, with what might be a snake coiled around a tree branch. b XRR, courtesy of Adri Verburg, KMSKA. The yellow rectangles on the XRR indicate two detail areas shown underneath. Detail 1 highlights the bearded man wearing a hat. Detail 2 was processed with the Platypus software to enhance the details and contrast of the face of a second figure. c–e MA-XRF imaging: the elemental distribution images of manganese (Mn-K), mercury (Hg-L), and iron (Fe-K) reveal more details on the standing and kneeling figure.

As noted by Zwakman33, it appears Ensor painted a religious scene, possibly featuring the apostle James the Great. The iconographic interpretation suggests that the figure on the left wears the typical attributes of a pilgrim, such as a red, draped pallium, a staff with a gourd, and a broad-brimmed hat with a lifted front, whereas the MA-XRF images suggest he might be wearing a belt with a flask. His bare feet symbolize Christ’s path, which might identify him as an apostle34. Further analysis of the MA-XRF data revealed additional, more challenging details to interpret. On the right side, a shape emerges that could be identified as a snake coiled around a tree branch. The manganese (Mn-K) map reveals a few strategically placed paint dots, which seem to represent the eyes of the snake (see Fig. SI-6a). However, the partial reconstruction did not allow for an identification of the full scene. The composition must have been painted between 1877 and 1880, when Ensor studied at the Brussels Academy. In this period, the training to become a painter was still based on the classical artistic tradition33 and students were therefore asked to copy or paint multiple religious and mythological scenes. According to Van Heesch35, Ensor participated in the course “Historische composities” (Historical Compositions), where students were tasked with creating original works inspired by themes from the Bible or Greco-Roman mythology. This makes it plausible that the underlying composition is not a copy of an existing painting, drawing, or etching, but an original composition conceived by the artist.

Type 4: Metamorphoses—Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat

Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat (1883–1888, Mu.ZEE), shown in Fig. 6a, is one of the 14 paintings that are believed to have been reworked by Ensor, years after finishing the paintings. Art historians Haesaerts22, De Maeyer19, and Todts25 based their theory on stylistic and iconographical anachronisms, as well as IRP and XRR imagery. Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat was initially hypothesized to be an early self-portrait by Ensor, dated 1883, featuring his characteristic dark color palette. Around 1888, Ensor added the colorful flowered hat, details in the mustache, and round arches in the corners. In 2012, Van der Snickt20 provided material-technical evidence for the theory of the later reworking by performing Portable X-Ray Fluorescence measurements. Cadmium yellow was found in the yellow flowers of the hat, a pigment that was not part of Ensor’s color palette, yet at the time that the early self-portrait was made. UIVFP of this painting shows a pink fluorescence (Fig. 6j), indicating the use of a red lake, another pigment that was not used by Ensor before ca. 1888, as was already discussed in the case study of Woman with Upturned Nose.

a Visible light photograph of Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat (1883–1888, Mu.ZEE), courtesy of Adri Verburg, KMSKA. MA-XRF scanning area is marked in yellow. A reconstruction of the two overpainted signatures and dates has been added in white. b–d MA-XRF element maps: chromium (Cr-K), zinc (Zn-K), and cadmium (Cd-L), all present only in later additions, such as the hat flowers and corner arches. e Lead (Pb-L) map showing its presence in both the ground and paint layers. f The cobalt (Co-K) map shows how the original background was more blue than currently visible. g, h Iron (Fe-K) and mercury (Hg-L) maps corresponding to the original dark, realistic portrait. In both images, an overpainted signature was found, indicated with a yellow rectangle. This area is shown in detail in (k). i Overview of the areas where details were taken. j Detail of the UIVFP image showing a local varnish on the face, courtesy of A. Verburg, KMSKA. k MA-XRF composite map of iron (green) and mercury (red) revealing two overpainted signatures: “J. Ensor 85” (vermilion) and “Ensor 85” (red/brown pigment). l, m Details of the visible signature and date “J. Ensor 1883” under visible light and under UV light. n Micrograph showing white-pink paint covering horizontal cracks in the paint layer below, indicating the time between the original portrait and the pink additions. o Micrograph of the cheek showing a skin-colored paint layer on top of a thick, locally applied varnish.

Although the additions were made after the initial completion of the painting, the reworking on Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat cannot be considered as the aforementioned Type 2: post-factum revision. Instead, it is classified as a metamorphosis, which refers to an alteration that transforms its original meaning or intent. The physical intervention can be both limited and extensive, but rather than being a minor adjustment or refinement, this type of reworking fundamentally redefines the painting’s narrative, theme, or conceptual focus. It suggests that the artist revisited the piece with a fresh perspective, effectively creating a new interpretation of the work. Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat began as a traditional self-portrait, rendered in thick impastos and showing affinities with Impressionism. However, the subsequent addition of the feminine, masquerade-like flowered hat, the exaggerated and grotesque mustache, and the arched shapes in the corners—resembling a mirror or medallion—evokes the conventions of Baroque portraiture. These theatrical elements transform the conventional self-portrait into a grotesque and self-conscious one, engaging themes of femininity and travesty, and thereby radically altering the painting’s subject and tone30. While it was long believed that Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat was inspired by Rubens’ self-portraits, Todts has recently suggested a different influence: Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat (1782, The National Gallery, London) by Madame Vigée-Lebrun, one of Ensor’s favorite artists36.

The painting was scanned with MA-XRF to study the metamorphosis and identify changes. The scans revealed differences in pigment use between the portrait and the later additions. Zinc (Zn-K) appears only in brushstrokes that are part of the revision, i.e., the flowers on the hat, strokes in the black vest, and the round arches (Fig. 6c). Zinc appears to be present as zinc white mixed with other colors, but could also be present as an extender in those colors. Chromium (Cr-K), linked to a green pigment, is found in addition to the flowered hat, eyes, and mustache (Fig. 6b), while cadmium yellow is used in the hat’s yellow flowers (Fig. 6d) and shows weak antimony signals. Elements such as iron (Fe-K), mercury (Hg-L), and cobalt (Co-K) are mostly linked to the original portrait (Fig. 6f–h), whereas lead (Pb-L), sulfur (S-K), potassium (K-K), manganese (Mn-K), barium (Ba-L), strontium (Sr-K), and calcium (Ca-K) can be found in both the original portrait and the additions. The presence of cobalt in the background suggests that the background was initially more blue(ish) and was later overpainted with a warm brown color (Fig. 6f). Parts of this blueish background are still visible to the naked eye near the edges of the painting (not scanned with MA-XRF) and in particular in one of the lacunae in the upper right corner.

Digital 3D microscopy (Hirox) revealed that some of the additions were applied over an already cracked paint layer, indicating that a significant amount of time must have passed between the initial painting of the former self-portrait and the revision (Fig. 6n). Furthermore, a strong greenish fluorescence visible under UV light, confined to the area of the face only, indicates the presence of a thickly applied varnish containing drips. Under magnification, it appears that the additions to the face were made on top of this thick varnish (Fig. 6o). In some areas, both the varnish and the retouches applied over it have cracked. Artists were advised against painting directly onto a varnished surface to avoid such issues. Instead, a retouching varnish—a thin, fast-drying layer—was recommended. Such thin varnish was believed to improve adhesion between the dry paint and new additions, reducing the risk of cracks forming alongside the varnish37. Carlyle describes how retouch varnishes were also used to revive dull or sunken in paint and to work over partially dried layers without disturbing the underlying layer38. The varnishing practices of Ensor and his contemporaries are complicated and remain understudied and will be the subject of a follow-up paper.

Although the painting bears a visible signature, “J. Ensor 1883,” in a brown-red color (Fig. 6l), it seems likely that the painting was backdated by Ensor himself. UIVFP imaging demonstrated how this signature fluoresces faintly pink under UV light, indicating the presence of a red lake pigment (Fig. 6m). As mentioned earlier, (see Type 2: Post-factum revisions) Ensor employed this organic pigment from around 1888 onwards, hence suggesting that this signature was not applied in 1883, but added at the time of reworking. Furthermore, the MA-XRF scans uncovered two overpainted signatures in the lower-right corner, both accompanied by the date “1885.” It is assumed that these were covered when the arches were added around 1888. The lowest signature is painted in vermilion (HgS), and thus appears in the mercury (Hg-L) (Fig. 6k) and sulfur (S-K) maps. The upper signature (Fig. 6k) contains iron (Fe-K), barium (Ba-L), and calcium (Ca-K), and emerges in the zinc and cobalt maps. An informed observer can still see traces at the paint surface of the upper red/brown signature, as this was not entirely overpainted. The most surprising aspect of these two overpainted “1885” signatures is the 2-year difference with the still visible 1883 signature. Given that the visible 1883 signature is associated with the later additions, it is unlikely that the portrait was originally created in 1883. It is more likely that the portrait was made in 1885 and that both signatures and the accompanying 1885 dates were overpainted when the arches in the corners were added around 1888. It is then around 1888 that the painting was backdated to 1883. As Todts mentioned in his PhD thesis, Ensor was obsessed with chronology and is known to have backdated several paintings and drawings, thereby enhancing both his personal significance as a pioneer and the modernity of his work39.

Type 5: Appropriation—The Adoration of the Shepherds

The Adoration of the Shepherds (1887, RMFAB) was originally a nineteenth-century painting by another, unknown artist, but Ensor transformed the peasant scene with thick brushstrokes into an adoration of the shepherds. As the revision clearly altered the painting’s meaning, Todts classified this painting in the same category as Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat25. In this paper, the work is not classified as a Type 4—metamorphose. Instead, this reworking by Ensor of an existing painting by a fellow artist is labeled as appropriation, a term described by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York as “… the intentional borrowing, copying and alteration of existing images and objects” (Museum of Modern Art)40.

Ensor mentions the creation of The Adoration of the Shepherds in one of his letters, dated 27 December 1923: “Thus, to sum up, the figures, etc. are by me, but the peripheral elements in the upper portion are by a painter from the 1840’s. In this, the piece is an unusual and peculiar concoction, for it is not the work of my hand alone. Furthermore, it is the only one of its kind.”41 The peasant scene painted by the unknown nineteenth-century painter depicted farmers around a table, situated in a shed, reminiscent of genre scenes of old masters such as Adriaen Brouwer (1604–1638) and David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690). The IRR and IRP show an underdrawing that was loosely sketched with spontaneous lines, visible in the reconstruction of the underdrawing in SI (Fig. SI-7a). The execution in paint is quite detailed in some parts, such as the roof of the barn, but the overall scene seems to have stayed unfinished. The paint was applied thin, without the use of impasto’s and the scene is mainly executed in brown tones. The hand of the unknown nineteenth-century painter contrasts with the thick brushstrokes and vivid colors Ensor added around 1887 when he reworked the painting.

MA-XRF analysis of the painting reveals that certain elements appear exclusively in the reworked areas and are absent in the original peasant scene. This indicates the use of a different palette by the two painters, making it easier to distinguish the original peasant scene from the later reworking. The elements only found in the additions by Ensor are copper (Cu) and arsenic (As), corresponding to Emerald or Scheele’s green; chromium (Cr), present in both chrome green and chrome yellow; and potassium (K) as part of various artists’ materials. In addition to pigment information, the elemental maps also provide insights into paint application and technique. While most maps containing elements from Ensor’s reworking show how he applied his paint in thick, expressive brushstrokes, the chromium map (Figs. 7d and SI-7b) highlights how he painted small dots of paint on the clothing of two figures, likely to mimic the appearance of brocade. Zinc (Fig. 7e) is the only element exclusively associated with the original peasant scene, with no connection to the reworking. It might be present in the paint as an adulterant or mixed with other pigments to lighten the hue of the paint.

a Adoration of the Shepherds (1887, KMSKB). Photograph by R. Klein Gotink for the Ensor Research Project (KMSKA, 2013–present). b, c MA-XRF distribution maps of copper and arsenic, present only in Ensor’s reworking brushstrokes. (d) Chrome distribution, showing a thick, spontaneously applied chrome green layer in the upper-left corner, added by Ensor. e Zinc distribution, corresponding to zinc white in the original peasant scene, possibly as a paint tube additive or mixed in by Ensor to lighten hues. f Mercury distribution (vermilion), used in the original scene and Ensor’s reworking, seen in thick strokes on the lower part of the painting. g Manganese distribution corresponding to the early stages of the original painting, revealing original peasant details such as stance and attire. h, i Iron and cobalt distributions. j Detail of Adoration of the Shepherds. k IRR detail showing the original seated position of the right-hand man, with his legs under a table. Reflectography by A. Verburg for the Ensor Research Project (KMSKA,2013–present). l Reconstruction of the right-hand man’s position: white lines indicate the original position based on the IRR; red lines show Ensor’s reworking, converting him to a kneeling figure.

Other elements are found in both the original peasant scene and in the additions by Ensor: vermillion (Hg-L), bone or ivory black (Ca-K), and lead white (Pb-L and Pb-M). The latter is present over the entire surface of the painting, suggesting that lead signals are at least partly stemming from a lead-containing preparation. Lead white was used in the pictorial paint of the original peasant painting and is found as the main white pigment in Ensor’s brushstrokes as well. Manganese is present in the brown tones of the original peasant painting and in the green paint strokes of Ensor’s additions. The manganese-containing pigment in the original peasant painting may have been applied during the ébauche phase to indicate darker areas, loosely defining the peasant figures with broad, rough contours in certain places, applied with a large, stiff-bristle brush. By outlining the original forms of the figures, this layer (Fig. 7g or SI-7c) clarifies aspects of their original poses and attire. Notably, the standing figure appears to have once worn something on its back: he might have had a smaller headdress and was wearing trousers, rather than the robe which is currently visible. The figure on the right was wearing a more triangular-shaped hat. The underdrawing reconstructed in SI (see Fig. SI-7a) provides a clearer view of the original pose of this person. He was originally seated on a chair and leaning backwards, with his feet positioned beneath a table (Fig. 7l, white lines). Ensor changed this table into a crib for the Christ Child. The legs of the sitting figure were changed into supporting legs of the crib. Additionally, the chair he is seated on was overpainted, and the posture of the figure was transformed into a kneeling position (Fig. 7l, red lines). Ensor changed the peasants’ outfits into royal robes and most likely changed their faces slightly. In the upper-left corner of the background, a thick layer of dark green paint was applied, displaying visible rheology in the brushstrokes. Changes are also evident elsewhere in the background, particularly on the right side, where the window was originally smaller and depicted as open, as illustrated by the reconstruction of the underdrawing in Fig. SI-7a. This initial version of the window was painted in a rudimentary manner by an unknown nineteenth-century artist, but Ensor later overpainted it entirely, obscuring the open window and enlarging its size. On top of the cabinet, behind the original open window, the initial artist appears to have sketched a vase or basket, and in the lower right corner, the underdrawing reveals what may have been a basket, crib, or chair. Both objects were likely never painted, as they do not appear in any elemental map. These latter two objects may represent pentimenti by the original artist, sketched in pencil but ultimately left unexecuted in paint.

Discussion

This study has examined the diverse ways of reworking in James Ensor’s oeuvre by analyzing technical, stylistic, and historical evidence. Building on previous observations by Haesaerts, De Maeyer, and Todts, five types of reworking practices were identified: pentimenti, post-factum revisions, recycling, metamorphoses, and appropriation, thereby providing valuable insight into Ensor’s studio practice and artistic decision-making.

In particular, the analysis of Ensor’s The Skeleton Painter revealed pentimenti both between the underdrawing and the paint layer, as well as within the paint layer itself. This indicates that, despite starting with a photograph and an initial pencil sketch, Ensor did not adhere rigidly to his original concept. A similar compositional process can be observed in two of Ensor’s etchings, both titled My Portrait as a Skeleton (1889), which were also based on a photograph of Ensor, standing in front of a window. The first version (SM001412a, Mu.ZEE) is almost an exact copy of the photograph showing Ensor’s self-portrait, while the second print, derived from the same etching plate (SM001412b, Mu.ZEE), depicts Ensor’s face reworked into a skull and with the addition of another faintly discernible skull on the windowsill35. By combining MA-XRF with IRP, it became evident how the artistic process and decision-making in The Skeleton Painter evolved to shape the final composition.

Pentimenti offer a glimpse into an artist’s painting process, and by examining these examples alongside Ensor’s work, we can better understand the unique aspects of his methodology compared to his contemporaries. For instance, the IRR of Gustave Caillebotte’s (1848–1894) Boats and Shed on the Bank of the Seine (1891) reveals that he rotated the canvas and began anew after an initial, likely oversized, boat sketch31. A similar situation is seen in Ensor’s Bathing Hut on the Beach (1876)42. Notably, not all pentimenti occur in the underdrawing. Edvard Munch’s (1863–1944) first version of The Sick Child (1885-86) developed over an extended period. During this time, Munch repeatedly scraped off and reapplied paint, struggling to achieve the emotional expression and surface texture he sought for the piece43.

However, pentimenti can prove challenging to trace in his early works due to his spontaneous and instantaneous painting method. Most of Ensor’s early paintings (1880–1885), produced after his time at the Academy of Brussels, were not based on pre-designed compositions. Instead, they were created directly from real-life settings and painted straight onto the canvas. As a result, these works were constructed spontaneously and quickly, with little to no use of carbon-based underdrawings. In certain paintings of that period, there are traces of what could be a painted sketch25. However, painted sketches are difficult to detect, as they are covered by subsequent paint layers, while Ensor’s spontaneous painting style makes it difficult to distinguish a sketch from the actual paint layers. MA-XRF imaging is only successful in visualizing these sketches when the pigments in the underpaint contain chemical elements that are (a) different from the constituting elements of the superimposed pictorial layer, and (b) if the paint buildup is favorable. The latter implies a combination of a thin surface paint, high-Z elements in the underlying sketch emitting sufficiently energetic X-ray fluorescence signals to penetrate the top coating(s) and a relatively X-ray transparent surface paint. Usually, these conditions are not applicable for the entire painting, but are only fulfilled in some subareas, with elemental distribution maps exhibiting local “windows” to the underlying sketch. In Ensor’s later works, pentimenti become more visible, not necessarily because they occur more frequently, but because carbon-based underdrawings are more frequently detected through IRP and IRR, occasionally revealing alterations between the initial sketch and the final paint layer. Moreover, painted sketches are more often visible to the naked eye in his later period, as the overlying paint layers were applied thinly. In this period, the painted sketch took on greater importance, being applied not spontaneously but with meticulous care, and it was not always fully covered by subsequent paint layers.

Post-factum improvements do not alter the composition or content of the works, but are thought to be additions to either make the painting more lively and vivid, give a signature a more prominent or better position in the composition, or involve retouching as part of a conservation effort done by Ensor himself on areas with paint losses (e.g., on some parts of Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 from the J. Paul Getty Institute)44. It is known that some of his paintings remained in his studio for years, which would have allowed him to rework them over time. Examples of paintings with such touch-ups are The Stove (1880, 1882 (?), private collection), where the reworking is present underneath a varnish layer; and Fisher Couple (1873–1875, Mu.ZEE, see Fig. SI-4). In both works, the UV-fluorescent red lake was found, while the latter also contains small touch-ups with pure zinc white, a pigment associated with Ensor’s later period. Although madder lake was commercially available, it was not part of Ensor’s painting palette in his early years20. Based on the investigation of ca. 120 UV-images, the use of this particular under UV-fluorescent madder lake appears to begin around 1888, making the presence of this lake on Woman with Upturned Nose a material-technical anachronism. Madder lake serves as a strong marker for periodization, as it is easily detected under UV light. The same applies to zinc white, which fluoresces green under UV light; however, further research on its use in Ensor’s oeuvre is needed before it can be reliably used as a periodization reference. Although Ensor rarely documented his reworking practices, occasional insights can be obtained from his correspondence. For example, in a letter to Ernest and Mariette Rousseau dated May 1884, he writes: “I’m working a lot now! I’m repainting old studies and canvases. I’m either fixing them up or ruining them.” 45 While the precise nature of the repainting he refers to—and the specific works involved—remains unclear, such remarks offer valuable context for the material-technical evidence of reworking across his oeuvre.

Another notable form of post-factum revision frequently observed in Ensor’s oeuvre is the inclusion of multiple signatures within a single painting. In some cases, the original signature was overpainted, as seen in Self-portrait with Flowered Hat and also on other paintings, e.g., Flowers and Vegetables (1896, KMSKA) and Still Life with Chinoiseries (1880, KMSKA). In other instances, the two signatures simply remain visible, such as in Lady with the Fan (1880 or 1881, KMSKA), The Cabbage (1880, RMFAB), and The Skate (1892, RMFAB). In Bottles (1880, Fondation Socindec), the initial signature may have been concealed by the frame, prompting Ensor to add a second signature in a more prominent location. Additionally, some paintings exhibit evidence of reworked signatures, where the original has been traced over in either the same or a different color, as seen in The Wait (1879, KMSKA) and Azaleas (1920–1930, KMSKA). Apart from that, dates are often applied in a different material or color than the signature, suggesting they may have been added later. In an undated letter preserved in the Mu.ZEE archive, Ensor wrote to pharmacist Mathijs Gant, who had recently acquired his painting Willy Finch in His Studio (1880, Musea Sint-Niklaas). Ensor confirmed the painting’s signature in the lower right corner. However, the presence of a second Ensor signature in the upper left prompted Ensor to explain, “It sometimes happened to me, from 1880 to 1885, that I painted over my old studies that I considered unsuccessful; thus, the Ensor signature at the top left, perhaps poorly covered, can be explained.”46 This suggests the upper-left signature may originate from an underlying composition and was inadequately concealed during overpainting, resulting in two visible signatures. While this offers a plausible explanation for double signatures on some paintings, it does not account for all instances.

The post-factum revisions encountered in Ensor’s works suggest efforts to “refresh” works for sale or exhibition. However, this is not always the main motivation for all Modernist painters. Consider Renoir’s The Umbrellas, revised in two distinct phases. During the first phase in 1881, Renoir depicted women wearing dresses fashionable at that time. In the second phase, in 1886, he reworked some of these dresses to reflect the styles that were in vogue 5 years later. This later reworking was confirmed when anachronisms in pigment use were detected; as mentioned by Roy et al., the second-phase adaptations involved pigments that Renoir had not yet used in 188116. In Nolde’s oeuvre, some paintings were reworked by accentuating shapes or enhancing colors with small brushstrokes, as seen in Selbstbildnis (1899) and Festmädchen (1918). These wet-on-dry additions, often matte, signal a period of time between the initial completion and the reworking of the paintings. Their presence in early works, anachronistic to his early style, points to his later impressionistic/expressionistic style. Such revisions are primarily seen in paintings that remained in his possession17.

Ensor recycled canvas during his academic period (1877–1880) and in the years immediately following, potentially indicating financial constraints as a young artist. In a letter addressed to Mathijs Gant46, Ensor explicitly mentioned overpainting earlier compositions between 1880 and 1885. This statement is substantiated by XRR imaging, which reveals numerous complete overpaints and confirms that canvas recycling was common in his early period (1873–1885). Significantly, no evidence of such recycling has been identified in his later works. Paintings dating from his student days at the Brussels academy generally show more zinc and barium in the paint as extenders, indicating student-grade supplies. However, in general, Ensor seems to have recurred to high-quality materials throughout his career20. It is possible that, early in his career, Ensor faced financial pressure due to limited sales, prompting him to reuse canvases. Yet, in his first 5 years, he produced over 160 paintings, working almost nonstop. It is therefore not unthinkable that the reuse of canvases was prompted by his rapid pace of creation—at times lacking fresh canvases and therefore repurposing older works. Additionally, the practice of overpainting study pieces may have been a common habit among artists or even a technique taught in art academies. This approach may have been part of a broader educational emphasis on economical use of materials, akin to practices observed in other crafts. However, a shift in the artistic style of the artist can also provide a complementary explanation. Ensor struggled to conform to the Academy’s idealized, formal style35. After leaving the academy dissatisfied, Ensor embraced realism and may have recycled canvases from his student years due to a disinterest in earlier works. As such, the quick individual evolution of artists’ creative mindset and, by extension, the overall increasing pace in stylistic evolution of that era, may have been an additional stimulus for Modernists to dismiss earlier works, next to their progressing technical skills. In the letter to Mathijs Gant, Ensor also mentioned that he overpainted some of his old studies because he considered them unsatisfactory46. Unlike Van Gogh, whose canvas reuse is linked to financial struggles documented in letters to his brother Theo47, Ensor’s motive for recycling canvas appears to have been driven by other considerations. The recycling of canvas in Van Gogh’s oeuvre is also particularly present in his early period12. As noted by Hendriks et al 47. Van Gogh not only recycled canvases but also utilized the reverse side of completed works and opted for cheaper support materials, as a way to use painting materials sparingly.

Ensor’s more extensive reworkings involved reinterpreting older pieces (metamorphoses), integrating them into his modern esthetic. Years after Ensor painted and reworked Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat, Pablo Picasso undertook a similar process with Self-Portrait with a Wig (c. 1898–1900). Picasso painted his self-portrait over a recycled canvas of a bearded man, later adding a seventeenth-century wig and cravat15. This re-imagining mirrors Ensor’s Modernistic reworking. While Picasso is known for such meaning-altering reworkings48, it is unclear if other Modernist painters reinterpreted compositions like Ensor and Picasso did. Self-portrait with Flowered Hat exemplifies Ensor’s innovative practice through both its altered subject matter and backdating. Todts noted in his doctoral research that Ensor deliberately maintained confusion around the dating of his works. This claim is substantiated by material-technical analysis of the painting, which provides evidence of antedating. Todts explains that Ensor failed to indicate that certain works were created in two separate phases, frequently adding grotesque elements, such as masks or skulls, long after the original, more realistic composition had been completed. This strategy created the illusion that the dramatic stylistic shift from realism to a grotesque style occurred within a single, early phase of his career. In doing so, Ensor strategically exaggerated his role as an artistic innovator. In reality, these works were executed in distinct phases, with a significant temporal gap that allowed for the evolution of Ensor’s technique, style, and material use, thereby yielding a contrast between realistic and grotesque elements39. These material insights not only contextualize Ensor’s revisions but also invite a broader examination of how modern artists navigated reworking as both a practical and conceptual strategy.

Additionally, Ensor claimed in a letter that The Adoration of the Shepherds is a reworking of a composition by an unknown nineteenth-century artist41. This claim was supported by the material-technical analysis, revealing significant differences in technique, style, and materials, confirming the presence of two distinct artistic hands. Ensor’s act of appropriation is regarded as innovative by art historians De Maeyer and Todts, who drew parallels with the Surrealist technique of Cadavre Exquis39. The latter is the term to refer to a collaborative experiment where multiple artists contribute to a text or drawing without knowing what the others have created. This process results in surreal, fragmented, and often distorted artworks49. As Ensor noted himself in his letter of December 27, 1923, The Adoration of the Shepherds was the only one of its kind, meaning that it was the only example of appropriation performed by him. However, there is at least one other painting in Ensor’s oeuvre that features work by two different hands. This is not an appropriation but more likely a collaboration between Ensor and Belgian artist Guillaume Van Strydonck (1861–1937). This painting, Dunes (Musée Charlier, near Brussels (BE)), was painted in July 1885. This work bears the inscription, « commencé par G. G. Vanstrydonck, terminé J. Ensor » (begun by G. G. Vanstrydonck, completed by J. Ensor)41. The key difference between The Adoration of the Shepherds and Dunes lies in their context: while The Adoration of the Shepherds was reworked without the original artist’s knowledge, Dunes was the product of a deliberate and knowing collaboration. Collaboration and appropriation are practices that can be traced back to the Old Masters. Collaborations were particularly common, often driven by the specialization of artists in specific aspects of a painting. This division of expertise frequently resulted in joint compositions created through the contributions of multiple artists. Notable seventeenth-century examples include the partnerships between Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625) and between Rubens and Frans Snyders (1579–1657)50. Occasionally, these collaborations or acts of appropriation led to a complete reinterpretation of the original artwork. For instance, as noted in the introduction, Rubens’ Landscape with Psyche and Jupiter exemplifies such a transformation, as the original landscape was painted by Paul Bril. However, not all “Rubenized” works involved such significant changes. In many cases, Rubens introduced only subtle revisions to existing works, preserving much of their original intent while enhancing or refining particular elements2. The above-mentioned cases of appropriation found in literature—seen in earlier artists like Rubens and later embraced by Surrealists—have a broader historical and artistic significance. Given its recurrence across periods and movements, appropriation is introduced here as a fifth, separate category.

While Ensor is known to have appropriated only one painting, the practice of appropriation grew in the mid-twentieth century, driven by consumerism and the increase of imagery in mass media40. Asger Jorn (1914–1973), known for his modification paintings, reworked found artworks into new scenes, imbuing them with fresh meaning and contemporary relevance. Interestingly, one of his modified paintings, Ainsi on s’Ensor (Out of This World—After Ensor, 1962), directly references Ensor. In this work, Jorn transformed a somber suicide scene painted by another artist into a grotesque mask scene, connecting his practice to Ensor’s distinctive style but not necessarily to his appropriation practice in the Adoration of the Shepherds51. Postmodern and contemporary artists have similarly appropriated existing works, for example, Jake and Dinos Chapman’s Insult to Injury series (2004), which involved drawing over etchings by Francisco Goya (1746–1828)1,52. By appropriating the works of other artists, figures like Ensor, Jorn, and the Chapman Brothers profoundly altered the meaning of the original pieces, often intentionally subverting the original artist’s intentions. In contrast, the practice of recycling reduces the original artwork (by the original artist or by another) to merely a substrate for a new composition, rather than altering its content.

In contrast to their predecessors, Modernist painters frequently painted for their own purposes, rather than working on commission. This resulted in a unique situation, with many works remaining unsold (for some time). On the one hand, artworks stayed in the artists’ studio for longer periods of time, creating the opportunity to rework them at a later point in time. On the other hand, this sometimes gave rise to financially unstable situations, stimulating artists to recycle their canvas. Artists, like Emil Nolde, reused canvases. For instance, his Die Bekehrung (1912) hides a partial landscape, and Selbstbildnis (1899) was painted over a plein-air landscape17. Beyond self-recycling, artists also painted over other artists’ works. Van Gogh recycled a landscape by another artist (a landscape, no longer visible due to the lining) multiple times, but without incorporating the original scene in his own work. After having painted a new composition on the still blank reverse side of the canvas, Van Gogh subsequently overpainted his newly made composition with Trees and Undergrowth (F309a, 1887, Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam), to then return to the verso side and cover the landscape by the original artist with a monochrome brown layer. Although never started, it was Van Gogh’s intent to use this layer as the colored ground for another new composition47. Decades later, Picasso completely obscured another artist’s painting of a general with his Le Gobeur d’Oursins (1946, Musée Picasso, Antibes)48. These examples highlight artists’ resourcefulness and, at times, their disregard for previous compositions in the pursuit of new creations. However, in the cases of Van Gogh’s Trees and Undergrowth and Picasso’s Le Gobeur d’Oursins, where the original work was created by another artist, this practice can also be viewed as a form of appropriation.