Abstract

This study developed the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) using deep learning to detect emotions in cultural heritage images on social media. By analyzing images of historical sites, intangible heritage, and artifacts, this research created a daily sentiment series linked to tourism intentions and user interactions. Results show that HSI accurately predicts public emotional responses and offline participation, especially during sensitive periods such as cultural disputes and disasters. Comparing image-based sentiment (HSI) with comment-based sentiment (CSI) reveals a dual-path process: images prompt immediate reactions, while comments influence delayed responses. When aligned, they amplify emotions; when competing, substitution occurs. This research highlights the emotional impact of heritage imagery in cultural tourism, offering insights for improving digital heritage experiences, multimodal content design, and visitor engagement strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the role of visual imagery in cultural heritage communication has become increasingly prominent. Visual information is vital for cultural expression. It subtly shapes public emotional perceptions and behavioral intentions. Prior studies have demonstrated that emotions play a critical role in predicting tourists’ decision-making, satisfaction, and revisit intentions1,2,3. Due to social media, digital exhibitions, and cultural tourism campaigns, cultural imagery has emerged as a primary channel through which the public engages in both emotional and cognitive interactions4,5. However, despite the ongoing integration of culture and tourism, systematic research on how emotional signals embedded in cultural images influence public attitudes and behaviors is unavailable. Increasingly, public interest in cultural heritage, travel motivation, and the cultivation of participatory conservation awareness are shaped by the emotional appeal of visual communication6. The emotional characteristics conveyed in images influence tourism intentions and consumer preferences, evoking empathy and motivating protective behavior in heritage crises. Consequently, there is an urgent need to establish a robust framework for quantifying cultural heritage scenarios in order to understand how image-based emotional cues guide public behavior. Such a framework would provide a theoretical foundation and an empirical tool for promoting cultural tourism, developing effective communication strategies, and conveying heritage risk messaging.

Building on AI-enabled image recognition techniques, this study develops a visual sentiment index —the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI)—to quantify the emotional responses evoked by heritage-related imagery.

Prior emotion research primarily relies on textual analysis, surveys, or interviews. The HSI adopts a visual-communication perspective and enables the quantification, temporal modeling, and population-level representation of emotional signals embedded in cultural heritage images. Technically, it establishes a scalable mapping from individual perceptual reactions to collective emotional states; theoretically, it reframes the analytical lens of heritage communication by shifting the focus from traditional “meaning interpretation and cognitive processing” toward the dynamic relationship between image-based emotions and public behavioral responses.

By integrating deep-learning–based sentiment recognition with time-series modeling, the HSI captures both immediate emotional reactions and lagged effects in heritage-related communication. It illuminates the temporal mechanisms through which visual emotions influence public behavior. This approach provides a quantifiable and traceable tool for measuring emotional dynamics in heritage contexts. It also advances cultural communication scholarship by extending the research frontier from cognition-centered frameworks to emotion-driven mechanisms, ultimately establishing a systematic analytical framework that links emotional signaling with public behavioral intention and engagement.

Building on this foundation, this research integrates public comments, engagement data, and cultural visual materials to examine the pathway linking image-based emotions to public behavior. This research offers three primary contributions:

Firstly, it demonstrates that emotional content in cultural heritage imagery significantly influences public engagement. This study developed a daily image sentiment index to measure the proportion of negative emotions in heritage-related images. Empirical results show that images depicting damaged heritage sites or cultural conflict lead to a decline in tourism intention, interaction frequency, and comment sentiment the following day. However, these adverse effects tend to diminish and even reverse over the subsequent days, suggesting that emotional responses to imagery are dynamic rather than fixed. This highlights that heritage images convey information, evoke emotion, and shape attitudes. These images play a crucial role in fostering cultural identity and participatory intent.

Secondly, it applies machine learning techniques to address key challenges in heritage image sentiment analysis—namely, subjectivity, high labor costs, and low reproducibility.

Emotion-rich visuals require scalable tools for analysis as cultural imagery becomes a dominant medium for public engagement7. Images are more effective in triggering emotional reactions than text8. However, their structural complexity and contextual dependence make manual annotation inconsistent and costly9,10. This research employed a convolutional neural network (CNN) model with transfer learning and probabilistic weighting strategies to automate sentiment detection in large volumes of social media heritage imagery, thereby enabling scalable, replicable analysis of cultural communication effects.

Thirdly, this study compared the behavioral predictive power of image sentiment (HSI) and comment sentiment (CSI) for heritage communication. Our findings reveal a “dual-path mechanism”: image sentiment provokes rapid emotional and behavioral responses, while textual sentiment operates through a delayed cognitive adjustment process. In high-emotion scenarios—such as post-disaster heritage imagery or controversial restorations—public attention tends to center on visual stimuli, reducing the explanatory power of textual sentiment (“functional substitution”). However, negative image and text sentiments may amplify emotional perception (“complementarity”), indicating that multimodal sentiment coherence enhances public sentimental engagement.

In tourism and cultural heritage communication research, the use of machine learning techniques has become increasingly prevalent11.

Gîrbacia12 and Furini et al.13 have used unstructured data to forecast behavioral trends, demonstrating the potential of artificial intelligence to model public engagement. Building on this approach, the present study employs Google’s pre-trained Inception v3 model. It is fine-tuned via transfer learning for sentiment classification of heritage-related images. The model analyzes compositional elements, color tones, scene context, and embedded cultural symbols to infer the emotional valence conveyed by each image. Empirical evaluation indicates that the model achieves 83.8% accuracy on the test set, demonstrating strong performance.

Based on this model, this research developed a daily Heritage Sentiment Index (HSIt) using cultural imagery published on Rednote and Instagram between April 2021 and May 2025. The image dataset covers major holidays, cultural festivals, and peak periods of heritage promotion. This ensures representativeness and temporal relevance. All images were retrieved using a combination of keyword filters, hashtag-based queries, and geolocation tags. This dataset provides a robust foundation for emotion modeling and behavioral prediction in the context of digital heritage communication.

This research further evaluated the predictive performance of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) across multiple dimensions, and the results reveal four key characteristics:

Association with public behavioral intentions

HSI exhibits a significant negative correlation with next-day public behavioral indicators, such as tourism intention, comment activity, and interaction frequency. Public willingness to engage tends to decline when negative emotional content is depicted. However, this decline is often followed by a partial rebound within 2–5 days, suggesting a temporary emotional shock.

Dual-pathway relationship with text-based sentiment (CSI)

Image-based sentiment triggers immediate responses due to its high perceptual salience and visual intensity, whereas text-based sentiment tends to operate through delayed processing pathways, exerting significant delayed effects. When image and text sentiments are emotionally aligned, they may jointly amplify public reactions. Conversely, in contexts of attention competition, one modality may suppress the influence of the other.

Amplification during emotionally charged events

The predictive power of HSI increases noticeably during periods of emotional concentration, such as heritage destruction, natural disasters, or media controversies. In such cases, the impact of image sentiment on public expectations and behavioral responses is approximately two to three times greater than in routine periods, underscoring the dominant role of visual emotion in crisis-driven cultural communication.

Robustness and generalizability

HSI demonstrates consistent predictive performance across various sentiment recognition approaches (e.g., probabilistic weighting vs. threshold classification), content sources (official vs. user-generated images), and temporal subsets. This consistency suggests strong external validity and theoretical generalizability.

In summary, HSI addresses the methodological gap in quantifying visual emotion in cultural heritage communication. It offers a scalable and automated tool for dynamically monitoring public sentiment and behavioral intentions.

Methods

This section outlines the technical framework for constructing the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) for cultural heritage imagery. First, the architecture and training approach of the emotion classification model are described. Next, the data sources and distributional characteristics of the collected cultural heritage image samples are introduced. Finally, the construction of the HSI variable and descriptive statistics for the emotional and behavioral variables used in the empirical analysis are presented.

Design of the image-based emotion classification model

The rapid advancement of computer vision techniques over the past few years has enabled the construction of highly accurate image classification models. In this study, we employ a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to recognize emotional cues embedded in cultural heritage images, aiming to minimize manual intervention in detecting subjective emotional expressions14. CNNs have been widely applied in visual recognition tasks, including building detection in remote sensing imagery15, historical site localization16, and socio-economic prediction17. You et al.18 applied CNNs to emotion classification from social media images, achieving high recognition accuracy. Their study is the most relevant for our research.

This study developed a model tailored for emotion analysis in cultural heritage imagery to identify emotional features embedded in visual content and examine their influence on public emotional responses and behavioral intentions. We adopted the Inception v3 architecture19. It is a high-performance convolutional neural network (CNN) widely recognized for image recognition. Initially designed for the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge, Inception v3 has demonstrated strong performance across a range of visual tasks due to its multi-branch convolutional modules and feature fusion capabilities20.

Our study employs a transfer learning strategy to construct an emotion recognition model tailored for cultural heritage imagery, enabling efficient classification with limited data21. This research used the Inception v3 model. This model is pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset using TensorFlow. We retained its core architecture while replacing the final fully connected layers to suit a binary classification task (positive vs. negative emotions). Overly fine-grained emotional categories can introduce subjective bias. Therefore, this study follows established practices in sentiment analysis22 by employing a simplified dichotomous classification scheme, enhancing the model’s consistency and reproducibility.

This research used the DeepSent image sentiment dataset developed by You et al.18 to support supervised learning. This dataset was annotated using the JD Crowdsource platform, with multiple rounds of consensus validation conducted to ensure label reliability. To enhance emotional consistency and model robustness, we retained only images with high inter-rater agreement, yielding a high-confidence training set of 1028 images. This refined dataset was used to fine-tune the model and optimize its performance. The optimized model produces stable probability estimates of emotional valence, providing the foundation for constructing the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and conducting subsequent analyses of public behavioral responses.

The dataset was partitioned into training (70%, 720 images), validation (10%, 103 images), and test sets (20%, 205 images). The model was trained with a learning rate of 0.01 over 500 epochs. On the test set, the model achieved 83.8% accuracy, 82.7% recall, 90.6% precision, and 88.9% F1-score. Figure 1 illustrates the accuracy trends during training and validation.

Although the DeepSent dataset is widely used in image sentiment recognition research18, it primarily features content from daily life and natural landscapes sourced from platforms such as Flickr and Twitter. As such, its compositional styles and emotional expressions differ significantly from those of cultural heritage imagery, potentially affecting the model’s generalizability in heritage-specific contexts.

To evaluate the model’s applicability to cultural heritage imagery, this study randomly sampled 200 images related to cultural heritage—covering themes such as architectural remains, intangible heritage practices, and exhibition activities—from Redbook (Xiaohongshu) and Instagram.

Before validating the DeepSent model, we conducted manual screening and semantic filtering to ensure the thematic relevance and representativeness of the evaluation samples. Specifically, images unrelated to cultural heritage—such as advertisements, selfies, and text-only posts—were removed from the initial pool. Two research assistants then independently reviewed the remaining images based on keyword semantics (e.g., “temple,” “heritage,” “craft,” “exhibition”) and visual content features (architectural heritage, exhibition scenes, craft demonstrations), retaining only those directly associated with cultural heritage. After this two-stage review, a final set of 100 images was selected for manual sentiment annotation and model comparison.

During the annotation phase, Ten JD Crowdsource workers were invited to classify each image into positive or negative emotional categories, and their labels were compared with the DeepSent model’s predictions. The results indicate that the model maintains strong performance in this context, achieving 74.3% accuracy, 90.2% recall, 74.6% precision, and an F1-score of 82.4%. The high recall demonstrates the model’s strong sensitivity and extensive coverage in detecting negative emotional signals, while the F1-score confirms its stable performance despite class imbalance.

Although the validation sample size is relatively small, the combination of manual semantic filtering and theme-balanced selection ensures the dataset’s semantic representativeness and cross-context relevance. This enhances the cross-domain applicability and effectiveness of the DeepSent model in cultural heritage image sentiment recognition tasks (see Table 1 for the confusion matrix).

To further illustrate the model’s ability to distinguish sentiment intensity, Fig. 2 presents typical image samples with the highest predicted sentiment probabilities. Specifically, Fig. 2a displays the top 15 images with the highest negative sentiment probabilities (i.e., highest HSI values), while Fig. 2b shows the top 15 images with the highest positive sentiment probabilities (i.e., lowest HSI values). These samples encompass representative cultural themes, including traditional architecture, intangible cultural heritage performances, and historical artifacts.

Figures A1–A15 present the fifteen cultural heritage images exhibiting the highest negative emotion probabilities (i.e., the largest HSI values), whereas Figures B1–B15 present the fifteen images exhibiting the highest positive emotion probabilities (i.e., the smallest HSI values). The selected images cover representative cultural themes, including traditional architecture, intangible cultural heritage performances, and historical artifacts.

Additionally, Table 2 supplements this information by reporting the corresponding sentiment scores of associated texts (CSI) for each image. Based on image captions and user comments, these scores were calculated using the Stanford CoreNLP model to assess the emotional tone of the accompanying textual content. All image samples were collected from Rednote and Instagram, spanning 2021 to 2025, ensuring both topical relevance and temporal representativeness.

Cultural heritage image samples

To ensure the representativeness of social media imagery and the reproducibility of our analytical results, this study employed a systematic, multi-stage sampling procedure to collect cultural heritage–related images from two major platforms—Redbook (Xiaohongshu) and Instagram. The data collection period spans from April 2021 to May 2025. The data covers several critical phases of global cultural heritage communication, including post-pandemic cultural revitalization, major international heritage conferences, and widely discussed cultural events. The final dataset maintains a balanced distribution across platforms, with approximately 53% of the samples originating from Redbook and 47% from Instagram.

The selection of these two platforms is grounded in their complementary roles and representativeness in visual cultural communication. Redbook is embedded in the Chinese social-media environment. It reflects East Asian communication norms characterized by emotional expression, community interaction, and lifestyle-oriented cultural narration. Its content often emphasizes everyday storytelling, emotional resonance, and the construction of cultural belonging within contemporary hybrid cultural contexts. Instagram, by contrast, presents a globally oriented visual narrative tradition marked by esthetic composition, symbolic reinterpretation, and cross-cultural creativity. With an internationally diverse user base and a high degree of cultural fluidity, Instagram offers a distinct perspective on global visual culture. The complementarity of these platforms enables the study to capture “Eastern–Western” visual expression patterns simultaneously. It provides a robust empirical foundation for examining cross-cultural mechanisms of emotional communication.

To further mitigate cultural-context bias and enhance cross-cultural robustness, we ensured balanced sample sizes and a uniform temporal distribution across both platforms, resulting in a relatively even structure spanning “local–global” cultural contexts. In addition, the visual sentiment recognition model used in this study relies on deep visual features—such as color patterns, texture, composition, and emotionally salient visual cues—rather than linguistic information or culturally specific symbols. Consequently, despite differences in narrative style and user demographics between Redbook and Instagram, the core emotional cues embedded in the imagery exhibit strong cross-cultural consistency. This allows sentiment measurements across the two platforms to remain comparable and reduces the likelihood that cultural bias will affect the study’s conclusions.

To improve the comprehensiveness and validity of sample retrieval, we adopted a parallel keyword strategy using both Chinese and English search terms, including “cultural heritage”, “intangible heritage”, “historic architecture”, and related combinations. All keywords were tested and refined through multiple rounds of manual screening to minimize semantic ambiguity and commercial interference. After image retrieval, publicly accessible samples were randomly selected, ensuring that no private or copyright-restricted content was included.

The subsequent cleaning and verification process involved two rounds of manual review. The first round removed advertisements, selfies, text-only images, product displays, and other content irrelevant to cultural heritage. In the second round, two research assistants conducted independent reviews based on image content and metadata, retaining only images directly related to cultural heritage themes such as architectural heritage, museum exhibitions, intangible heritage performances, traditional craftsmanship, and cultural festivals. To avoid temporal or platform-specific sampling bias, stratified random sampling was applied to balance samples across time (by quarter), platform (Chinese vs. global social media), and cultural heritage categories (five thematic types). This ensured representativeness and consistency in both temporal and thematic dimensions.

A total of 14,610 valid images were collected, averaging approximately 9.6 images per day (median = 10; IQR = 8–12), covering more than 120 notable cultural events and heritage-related activities. For each image, information such as visual content, associated comments, tags, engagement data, and timestamps was extracted and then fed into the sentiment classification model. The resulting Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) serves as the study’s core explanatory variable, capturing public emotional responses to cultural imagery and supporting subsequent empirical analyses.

This research strictly adheres to institutional ethical standards. All images and comments were collected exclusively from publicly accessible content on Redbook and Instagram and did not involve private accounts, personally identifiable information, or restricted-access materials. Only publicly posted cultural heritage–related images without copyright concerns were retained, ensuring the data sources were legal and transparent.

To avoid cultural misinterpretation or value bias, the research team incorporated cultural sensitivity principles during the screening and classification process. Images involving religious rituals, ethnic symbols, politically sensitive iconography, or potentially offensive content were subject to manual review and excluded where appropriate, thereby ensuring respect for diverse cultures and communities.

Furthermore, this study focuses solely on aggregate-level sentiment analysis and does not involve individual behavioral tracking, identity recognition, or intervention-based experiments. Therefore, no additional informed consent procedures were required. All research procedures comply with institutional ethical guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring transparency, rigor, and cultural respect throughout the study.

Variable construction

The core variable in this study is the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI), which quantifies the emotional characteristics—positive or negative—expressed in cultural heritage images encountered daily by the public. The HSI is based on the cultural heritage-related visual content dataset collected across multiple social media platforms featuring publicly shared cultural imagery.

In terms of variable definition, the HSI is calculated as the proportion of images identified by the model as conveying negative sentiment out of the total number of cultural heritage images published on a given day. The calculation is presented in Eq. (1):

Here, Negit is a binary indicator variable: it takes the value of 1 if the predicted probability of negative sentiment for image i on day t exceeds 50%, and 0 otherwise. nt denotes the total number of cultural heritage images collected on day t. This classification approach follows the modeling method for categorical sentiment assignment outlined by Barrett23.

For the empirical analysis, we draw on the sentiment index construction framework proposed by Tetlock24 and Neidhardt et al.3, incorporating the first through fifth lags of the image sentiment index (HSIt–1 to HSIt–5) as key explanatory variables. These are regressed against five types of public behavioral responses: Tour Intent, Engagement, Likes, Shares, and Review Emotions. The results presented in Table 3 Panel A and Fig. 3 show that the HSI exhibits significant and robust predictive power across multiple lag periods, confirming its effectiveness and applicability in research on emotion-driven public behavior.

Although the emotional classification of cultural heritage images is binary (positive or negative), the constructed Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) is a continuous variable that represents the proportion of negatively classified images on a given day. We additionally calculated an alternative version of HSI using the predicted probability of negative emotion for each image (denoted as NegProbit, see Eq. 2) to examine the robustness of the index. The results presented in Table 3, Panel B, and Fig. 4 show consistent predictive patterns across behavioral outcomes, providing additional evidence for the effectiveness and robustness of the HSI.

We employed an asymmetric dual-threshold strategy to examine the impact of threshold calibration on model estimation. Specifically, images with predicted sentiment probabilities below 0.5 were classified as positive, those above 0.6 as negative, while samples falling between these thresholds were treated as ambiguous and excluded from the index calculation. Based on this revised classification rule, a new HSI was constructed. The regression results show that the HSI continues to exhibit significant predictive effects across all behavioral models, with no substantial change in the lag structure. This confirms the index’s robustness and fault tolerance with respect to sentiment classification criteria (see Table 4 and Fig. 5 for details).

Another key objective of this study is to compare the relative predictive power of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and the Comment Sentiment Index (CSI) in forecasting public behavioral responses. Given that image sentiment is identified using deep convolutional neural networks that capture complex nonlinear feature relationships, we employed a consistent sentiment measurement approach for text data. Instead of relying on traditional lexicon-based methods25 (available at: https://stanfordnlp.github.io/CoreNLP/), to evaluate sentiment at the sentence level, the CSI was calculated as the average pessimism score across all user comments associated with each image26.

This research followed the analytical frameworks proposed by Zhang et al.27 and Ezzameli and Mahersia28 to systematically compare the functional roles of image-based (HSI) and text-based (CSI) sentiment signals. Specifically, we examined multimodal cultural heritage content shared on social platforms and assessed the marginal explanatory power of each sentiment type in predicting public behavior.

The Recursive Neural Tensor Network (RNTN) is particularly well-suited for the semantic analysis of short social media texts. It demonstrates strong adaptability to environments with concise and diverse expressions, such as user-generated comments. The model achieves a sentence-level sentiment classification accuracy of up to 80.2% and categorizes sentiment into three levels: negative (1), neutral (0.5), and positive (0)29.

We used this model to assign a sentiment score to each user comment at the operational level. The daily average pessimism scores were calculated to represent the overall sentiment intensity of comments, forming the daily Comment Sentiment Index (CSIt). This index was subsequently incorporated into regression models to examine the influence of textual sentiment on public behavioral responses. The CSIt is computed as follows (Eq. 3):

Where TextNegit denotes the pessimism score of the i-th comment on day t, and nt represents the total number of comments on that day. To mitigate the potential influence of outliers on parameter estimation, both the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and the Comment Sentiment Index (CSI) were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles30. Table 5 and Fig. 6 present regression results based on the unwinsorized HSI data to assess the robustness of the analysis. The findings remain consistent with the baseline results, further confirming the explanatory validity of the image sentiment variable and the robustness of the model.

This study used the Recursive Neural Tensor Network (RNTN) instead of traditional sentiment lexicon methods to extract sentiment features from cultural heritage-related texts. This choice is motivated by two key considerations. First, it ensures consistency with the image sentiment recognition framework in modeling complex semantic structures, thereby addressing the limitations of lexicon-based approaches in capturing contextual nuances31. For example, the phrases “ancient ruins are awe-inspiring” and “ancient ruins are dilapidated” may share similar vocabulary. However, their emotional implications diverge significantly—a distinction that lexicon-based methods often fail to capture, but RNTN can accurately process it using contextual parsing. Second, given the brevity and conciseness of text content on platforms such as Rednote and Instagram, RNTN demonstrates greater effectiveness in extracting meaningful sentiment signals from short-form user-generated content32. In contrast, conventional lexicons fail to capture a substantial portion of terms in this dataset, resulting in sparse or unusable sentiment scores, whereas RNTN shows superior sensitivity and accuracy in short-text sentiment detection.

Symbols and direction notes

The Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) represents the daily proportion of cultural-heritage images identified as conveying negative emotions. Accordingly, an increase in HSI indicates a higher share of negative-emotion images in the daily stream, reflecting a more negative visual information environment for the public.

Under this definition, the regression coefficient does not capture the valence of the emotions per se. Instead, it reflects the direction in which changes in the proportion of negative-emotion images influence behavioral outcomes:

Negative coefficients indicate that an increase in negative-emotion images (a rise in HSI). It suppresses subsequent behavioral responses—i.e., an “emotion intensification → behavioral decline” pattern.

Positive coefficients suggest that a higher proportion of negative-emotion images is associated with increased attention, interaction, or expressive behaviors—i.e., an “emotion intensification → behavioral rise” pattern.

The regression results presented in Table 3, Panel A, and Fig. 3 offer a clearer illustration of this emotion–behavior dynamic process: In lag 1 (HSIt−1), several behavioral variables exhibit significantly negative coefficients: Tour Intent = –0.037 (t = –1.832), Share = –0.041 (t = –2.177), Review Emotion = –0.042 (t = –2.178). This indicates that an increase in the proportion of negative cultural-heritage images on day t–1 significantly suppresses tourism intention, sharing behavior, and review sentiment on day t—an apparent emotional suppression effect.

At lag 2 (HSIt−2), the coefficients reverse direction and become significantly positive: Tour Intent = 0.050 (t = 2.001), Engage = 0.046 (t = 1.881). This pattern implies a rebound effect: after a one-day delay, the rise in negative-emotion images leads to heightened tourism intention and interaction behavior, reflecting a reversal or delayed compensation effect.

In summary, the dynamics of HSI can be understood as follows:

HSI increases → higher proportion of negative-emotion images → immediate behavioral suppression (short term), followed by a potential rebound effect at longer lags (medium term).

Descriptive statistics

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics for two key sentiment indices—the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and the Comment Sentiment Index (CSI)—and five categories of public behavioral variables. The dataset spans 1522 consecutive daily observations from April 2021 to May 2025. After accounting for lagged variables, the final sample comprises 1518 valid daily observations, encompassing major cultural events, intangible heritage festivals, and peak periods of heritage tourism.

Panel A shows that, on average, 21.9% of cultural heritage images per day were classified as conveying negative sentiment (HSI mean = 0.219), with substantial variation across time. This reflects strong emotional responses triggered by negative visual themes, such as damage to heritage sites, historical disputes, and the obsolescence of traditional customs. The average CSI score is 0.669. This value indicates that user comments tend to express more positive or constructive sentiments. The contrast between the emotionally charged nature of images and the relatively neutral tone of textual comments highlights the complementary nature of visual and textual sentiment expression.

Panel B reports the distribution of five public behavior variables. Subjective measures—such as tourism intention and comment sentiment—show relatively low volatility, suggesting stable emotional attitudes toward cultural heritage content. In contrast, objective behavioral metrics—such as likes and user engagement—are more dispersed, particularly given the notably limited sharing behavior. This may indicate a cautious approach to the public dissemination of cultural content, possibly influenced by perceived sensitivity or lack of shared identity.

Panel C shows a modest but statistically significant positive correlation between HSI and CSI (r = 0.085, p < 0.01), suggesting partial convergence in users’ emotional responses to both visual and textual content. Nevertheless, both expression forms operate in distinct ways. Cultural images continue to serve as an irreplaceable emotional trigger in digital heritage communication due to their symbolic and evocative power.

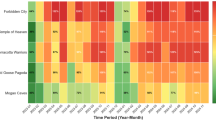

Figure 7 illustrates the daily and monthly trends of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and Comment Sentiment Index (CSI) throughout the sample period. Between 2021 and 2025, cultural heritage-related events frequently appeared on social media platforms, leading to notable fluctuations in both image and text-based sentiment indices. While the post-pandemic recovery created favorable conditions for offline cultural engagement, fluctuations in HSI and CSI remained driven mainly by external shocks, cultural controversies, and milestone heritage events. Several representative cases include:

In 2021, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and several other countries initiated the repatriation of Benin cultural artifacts, including the “Benin Bronzes,” royal objects from the Kingdom of Abomey33. Images documenting the return and exhibition of these artifacts circulated widely on social media, carrying sentiments of solemnity, respect, and cultural justice. Correspondingly, the HSI increased markedly. Keywords such as “historical justice” and “cultural return” frequently appeared in the comments, leading to a simultaneous rise in CSI, reflecting “emotional resonance and cultural identity” in the context of heritage repatriation.

In April 2022, multiple cultural heritage sites in Ukraine were destroyed during armed conflict. Images of the ruins spread across social media, triggering strong emotional reactions. Both HSI and CSI declined sharply, with comments frequently referring to a “cultural catastrophe,” illustrating the “emotional resonance and behavioral appeal” 34.

In December 2024, the reconstruction of the Notre-Dame Cathedral spire was completed. Images showcasing the restored architecture and the symbolic power of cultural renewal were widely shared online, eliciting positive emotional responses. The HSI rose significantly, and comments such as “respect” and “rebirth” became predominant, driving an upward movement in CSI as well.

In July 2024, UNESCO held the 46th World Heritage Committee meeting in New Delhi, during which China’s “Central Axis of Beijing” was inscribed on the World Heritage List. The event drew considerable public attention. Social media was flooded with related images expressing solemnity, admiration, and cultural pride, leading to a notable increase in HSI. Comment sections were similarly filled with terms such as “cultural pride” and “successful inscription,” resulting in a parallel rise in CSI.

In January 2025, China expanded its visa-free entry policy. This change attracted large numbers of European tourists to cultural heritage sites such as the Forbidden City, West Lake, and the Terracotta Army. Tourists shared extensive imagery showcasing awe and enjoyment. The HSI exhibited a substantial increase, and comments were dominated by phrases such as “cultural shock” and “ancient civilization,” which led to a rise in the CSI—an example of the “cultural attraction and emotional contagion” effect35.

This research observed that during cultural hotspots or moments of public controversy, trends in image sentiment and comment sentiment tend to move closely together. In contrast, in more stable periods or routine cultural activities, the gap between the two becomes more pronounced.

Notes: The daily series is smoothed using the LOWESS method (bandwidth = 0.02). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals, illustrating the range of uncertainty around the estimates. Monthly averages are not smoothed, as monthly aggregation naturally produces a stable low-frequency series; applying additional smoothing could obscure meaningful trends. In contrast, the daily series exhibits more pronounced high-frequency fluctuations, making LOWESS smoothing appropriate for highlighting overall patterns and improving interpretability.

Results

This study adopts a digital cultural communication perspective to investigate how emotional content embedded in cultural heritage images influences public emotional responses and behavioral intentions. By constructing two sentiment indices—the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) for visual content and the Comment Sentiment Index (CSI) for textual feedback—this research moves beyond the traditional cognition–behavior linear models (Baumgartner et al., 2006; Brown, 1999), emphasizing affective cognition and multimodal information integration mechanisms.

Two theoretical premises support the empirical logic of this study:

First, cultural communication is not solely driven by rational information. Images are a highly perceptual medium. Imagery conveys emotional cues that more readily evoke affective resonance and subjective attitudes among viewers, such as feelings of nostalgia, esthetic appreciation, or reverence36,37,38. These emotional reactions often precede rational evaluation and directly shape individuals’ attitudes and willingness to participate in cultural experiences.

Second, individuals exhibit cognitive limitations such as “emotional regulation deficits” and “selective attention” when processing cultural information39,40. High-emotion imagery may trigger affect-biased processing or visual overwhelm, rendering rational textual explanations insufficient to counterbalance the emotional impact41. This suggests that in the visual dissemination of cultural heritage, the public often responds not as purely rational evaluators but as affect-driven participants.

Behavioral effects of image and textual emotions

This section presents an empirical evaluation of the predictive power of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and the Comment Sentiment Index (CSI) in forecasting public behavioral intentions. Three key findings are summarized as follows:

The emotional content in cultural heritage imagery has a significant influence on short-term public behavioral responses

When cultural heritage images posted on a given day exhibit strong negative emotional cues—such as scenes of destruction, conflict, or controversy—public engagement metrics (e.g., comment sentiment and interaction frequency) show significant fluctuations on the following day. This suggests that cultural heritage imagery, which integrates visual symbolism, historical memory, and emotional significance42, has a powerful capacity to trigger immediate public reactions, mobilize opinion, and even spark debate.

Visual and textual sentiments operate through dual and complementary pathways in cultural communication

Our analysis reveals that image-based sentiment exerts an immediate influence, whereas textual sentiment tends to have a delayed, compensatory effect. The two modalities rarely overlap in their behavioral impacts, indicating distinct emotional processing routes. When the sentiments expressed in images and accompanying texts are aligned, their effects may be synergistically amplified (complementarity); alternatively, audiences may shift toward an integrative judgment that privileges one over the other (substitution), forming a dual-channel mechanism under multimodal communication.

In high-emotion contexts, cultural heritage imagery tends to be dominant

Further analysis reveals that in emotionally charged scenarios—such as cultural trauma, heritage damage, or controversies over restoration—image sentiment profoundly influences public behavioral intentions. These images often convey powerful visual and symbolic cues. They evoke sensory responses and deep emotional engagement with themes of historical loss, cultural memory, and the preservation of values. In contrast, while textual commentary provides interpretive context, its mobilizing effect is relatively delayed in such situations, highlighting the visual primacy of images in the transmission of cultural emotions.

The Impact of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) on public behavioral Variables

Table 3 presents the core time-series regression results of this study. It presents the lagged effects of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) on various public behavioral variables.

The regression models (see Eq. 4) are constructed based on the analytical framework of Tetlock24 and Neidhardt et al.3, which examines how sentiment influences behavioral responses. To ensure robust statistical inference, t-statistics for the regression coefficients are estimated using the Newey and West43 heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation-consistent standard errors.

In the model specification, Bt denotes the log-differenced values of public behavioral variables on day t, including Tour Intent, Engagement, Likes, Shares, and Review Emotions. The core explanatory variable is the five-lag structure of the Heritage Sentiment Index, Q5(HSI). It captures the dynamic influence path of image-based sentiment on public behavior. The control variables χt include a constant term, day-of-week dummies, and holiday dummies to account for periodic fluctuations.

It is essential to note that the inclusion of HSIt−1 accounts for the temporal lag in sentiment transmission, where the public’s emotional and behavioral responses on day t are primarily influenced by the sentiment embedded in cultural heritage images circulated on social media platforms on day t–1. This lag structure is grounded in empirical reality. This is because platforms such as Rednote and Instagram typically exhibit a time gap between the actual occurrence of a cultural event and the public dissemination or engagement with related visual content.

Panel A of Table 3 presents the multi-period lagged regression results of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) on five categories of public behavioral responses, illustrating the dynamic transmission path of image-based sentiment. At the first lag (HSIt–1), the index exhibits statistically significant negative effects on variables including Tour Intent, Likes, Shares, and Review Emotions. The coefficients range from −0.035 to −0.042, and the t-statistics are significant at 5% level. These results suggest that when the public is exposed to cultural heritage images depicting destruction, decay, or conflict, the immediate emotional response suppresses their interest in cultural engagement and diminishes their motivation to share it further.

The visual symbols embedded in cultural heritage imagery often carry traces of historical trauma and collective memory. In the short term, such negatively charged visuals suppress public behavior through emotional inhibition. However, beginning with the second lag period (HSIt–2), the effect of image sentiment gradually shifts in a positive direction. Specifically, HSI shows statistically significant or near-significant positive associations with behavioral variables such as Tour Intent and Like. This suggests an adaptive mechanism whereby the public’s initial emotional response shifts from negative to positive over time.

This rebound effect may reflect a process of emotional recovery, a renewed appreciation of cultural value, or a deeper cognitive engagement with the imagery’s underlying significance. By the fifth lag period (HSIt–5), all behavioral variables exhibit positive coefficients (e.g., Tour Intent = 0.052, t = 2.132), suggesting that the initial emotional impact of cultural imagery is eventually rechanneled into an increased willingness to participate, express cultural identification, and offer affective support. The joint significance tests further confirm the cumulative effect across lag periods 2–5, validating the presence of a temporally progressive emotional adjustment mechanism in cultural heritage communication.

Panel B employs a probability-weighted sentiment index to assess robustness. The results show that when the HSI value is high (indicating a greater proportion of negative sentiment), public tourism intention, online engagement, and emotional expressions all decline significantly on the following day, reflecting a short-term inhibitory effect. However, by period t + 5, these effects turn significantly positive, suggesting that negative stimuli are gradually reabsorbed and reinterpreted by the public in the medium term, transforming into cultural engagement and emotional support. Joint tests further confirm the cumulative positive effects from t–2 to t–5.

Taken together, these findings indicate that the emotional diffusion of cultural heritage imagery follows a dual-path mechanism: “instant inhibition followed by delayed recovery.” While negative visual shocks trigger short-term defensive withdrawal, the medium-term emotional rebound reflects renewed cultural recognition and reinforced cultural identity.

Comparative effects of image-based and text-based emotional signals

This section compares the predictive capabilities of the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) and the Comment Sentiment Index (CSI). It explores whether a complementary or substitutive relationship exists between the two. Specifically, it investigates whether public responses to cultural heritage images are also influenced by the emotional atmosphere in the comment section. Do these two modalities convey similar perceptual dimensions, or do they instead activate distinct emotional mechanisms?

This research constructed a multivariate regression model to examine the joint effects of image-based and text-based sentiment on behavioral decision-making in cultural heritage contexts. The model includes the current-day image sentiment index (HSI), the comment sentiment index (CSI), and their interaction term (HSIt × CSIt) as core explanatory variables, regressed on five types of public behavioral responses. The regression results are presented in Table 7 and Fig. 8. The CSI is derived using a Recursive Neural Tensor Network (RNTN) to identify pessimistic sentiment in user comments on heritage-related images. To ensure consistency between visual and textual sentiment sources, the CSI is calculated from comments accompanying emotionally labeled images (see Eq. 5).

The model also incorporates the first to fifth-order lagged terms of public behavior variables, Q₅(Bt), along with their squared terms, Q₅(Bt2;), to account for behavioral inertia and nonlinear fluctuations. χt denotes the control variables. The interaction term (HSIt × CSIt) is introduced to examine whether image and text sentiment function as complements or substitutes in predicting public behavior44.

This study found that the image sentiment index (HSIt–1) exerts a significant negative predictive effect on public behavior. Even after controlling for text sentiment (CSI), HSI remains significant at the 1% level across all five behavioral variables—tourism intention, likes, comments, shares, and review sentiment (see Table 7). This suggests that when images depict scenes of decay, disaster, or sorrow, public participation and online engagement decrease substantially. Such a suppressive effect suggests that cultural heritage images serve as both informational media and emotional symbols. Their visual impact often conveys more profound connotations of historical loss and cultural crisis, which may trigger non-rational emotional reactions.

In contrast, while the comment sentiment index (CSIt–1) demonstrates some influence, its overall significance is relatively lower. This is likely due to the cognitive demands associated with processing cultural comments, which require linguistic comprehension, contextual interpretation, and cultural literacy. As such, the behavioral effects of textual sentiment unfold gradually, reflecting the time required for opinion formation related to heritage policy, cultural identity, and historical narratives.

In further analyses, the interaction term between image sentiment and text sentiment (HISt–1× CSIt–1) reaches marginal significance across several behavioral variables. This suggests that when emotional cues in cultural imagery and accompanying textual comments are highly congruent, public perception is amplified. For instance, when heritage images convey strong emotions such as reverence, anger, or sorrow, and user comments mirror these sentiments, the resulting multimodal emotional alignment intensifies public affective responses and increases the likelihood of engagement. This pattern can be interpreted as a “cultural emotion complementarity effect”45.

However, the limited statistical strength of the interaction term also implies a ceiling effect on this amplification. As emotional congruence between image and text increases, the marginal impact of each modality may diminish, reflecting a “perceptual substitution” mechanism. In such cases, individuals may shift from relying on a single information source to forming emotional judgments based on the integrated emotional atmosphere of the entire content environment.

Additionally, Table 8 and Fig. 9 present an analysis of the multi-period lagged effects of comment sentiment (CSI). The results reveal a transition from negative to positive influence over time, with the fifth lag (CSIt–5) showing a statistically significant positive impact on public behavior. This finding suggests that when individuals are initially exposed to negative comments—such as expressions of loss or anger—they do not immediately respond or engage with them. Instead, the emotional impact undergoes cognitive absorption and attitudinal restructuring. It gradually transforms into a heightened willingness to participate in cultural activities. This reflects a “delayed processing effect” 46, a pattern frequently observed in cultural communication contexts. When comment content relates to group identity, cultural values, or historical attitudes, individuals are more likely to reassess their stance after an emotional incubation period and subsequently engage in responsive behaviors.

Overall, image sentiment and textual sentiment represent distinct channels of information and mechanisms for emotional response. First, image sentiment exerts a stronger immediacy and visual impact, primarily activating rapid affective responses. In contrast, textual sentiment operates more gradually, being shaped by semantic interpretation and contextual cues, reflecting a delayed processing pathway. Under certain conditions, the two can exhibit a synergistic amplification effect (complementarity), whereas, in emotionally redundant contexts, they may trigger substitutive responses. This “dual-pathway mechanism” suggests that, in image-text integrated communication environments, the public is influenced by the direct affective cues of imagery and the interpretive atmosphere of accompanying comments. Together, these two forms constitute a compound mechanism through which emotional responses to cultural heritage are transmitted and shaped.

Image attention effect and the dominance of the HSI

This study further investigates whether cultural heritage images exert an “attention dominance effect” in digital dissemination contexts. That is, whether emotionally intense imagery (either highly positive or highly negative) can more effectively capture public attention, thereby diminishing the influence of accompanying textual commentary on behavioral judgments and emotional responses.

Research has consistently shown that images possess a comparative advantage over text in attracting public attention. For instance, Li et al.47 employed eye-tracking experiments to demonstrate that images are the most visually salient elements on newspaper pages. Similarly, Bakar et al.48 found that media advertisements featuring images are more likely to engage viewers and trigger consumption-related behaviors.

Building on these insights, this study proposes the “Heritage Image Sentiment Dominance Hypothesis”. It postulates that when cultural images convey concentrated emotional expressions, their explanatory power for public behavior becomes noticeably stronger. In contrast, the influence of textual commentary weakens accordingly. Conversely, when image-based sentiment is weak or ambiguous, textual content may serve as the primary source of emotional inference.

As shown in Table 9 and Fig. 10, under the condition of Et = 1 (i.e., when image-based emotional expression is salient), the lagged image sentiment index HSIt−1 exhibits a consistently significant negative association with all five public behavior models. The estimated coefficients range from −0.058 to −0.065, and the t-values range from −2.255 to −2.532. All of these values are significant at the 5% level, with some approaching the 1% threshold.

These results suggest that when the public is exposed to strong negative visual stimuli—such as depictions of artifact destruction, heritage site damage, or ethnocultural conflict—the emotional signals conveyed by images are more likely to elicit immediate, intuitive affective responses, demonstrating a high degree of perceptual primacy. As a high-sensory-load medium, visual imagery can trigger emotional evaluations without requiring complex semantic processing, thereby exerting a direct and instantaneous suppressive effect on public engagement.

Meanwhile, the intensity of emotional expression in cultural heritage images significantly influences the public’s attention. With strong emotional content in images—for instance, depictions of war-torn ruins or visually striking heritage artifacts—the predictive power of CSIt−1 notably declines. This indicates that the public becomes more absorbed by the image’s emotional impact, with a corresponding decrease in cognitive processing of accompanying commentaries. Such a pattern reflects an “attention saturation” or “emotional substitution” mechanism49. In these cases, heritage imagery evokes emotional responses that are often irrational, such as grief, reverence, or a sense of cultural awe.

Conversely, when image-based emotional expression is weak (Et = 0), the public relies more on textual cues to interpret the emotional context of cultural events. During these periods, CSIt−1 exhibits significant negative predictive effects, particularly for variables such as Likes, Shares, and Review Emotions. This suggests that the public’s emotional responses are influenced by semantic information embedded in comments, including cultural attitudes, historical interpretations, or value-based identifications.

This dual-pathway mechanism—“image dominance and textual supplementation”—highlights the competitive nature of attention allocation in cultural heritage communication. When image emotion is strong, the public forms rapid responses via visual perception, reducing the impact of textual interpretation. When image emotion is weak, commentaries become the primary source of emotional insight. Although visual content may theoretically enhance interest in accompanying text, in practice, highly emotional imagery appears to crowd out attention to comments due to perceptual overload, revealing a dynamic structure of “dominance and substitution” in the dissemination of visual heritage.

Which modality drives public behavior in high-emotion periods? — cultural images vs. public comments

This section examines the communicative advantage of cultural heritage images under highly emotional contexts, particularly involving heritage destruction or major cultural incidents. Building on prior studies that underscore the superiority of images over text in conveying traumatic or emotionally charged content50,51, this study further investigates whether such a dominant effect also holds in the realm of cultural heritage communication.

We adopted the “Emotion Index” construction logic proposed by TRMI52 to identify such “high-emotion periods.” Specifically, we extracted representative topics related to cultural heritage from social media and news platforms by filtering high-frequency keywords with negative sentiment (e.g., “anger,” “loss,” “regret”) and their associated sentiment scores. Based on this, we constructed a binary dummy variable Et :if the daily sentiment score exceeds its historical median, Et = 1 (high-emotion period); otherwise, Et = 0 (low-emotion period).

As shown in Table 10 and Fig. 11, during both high and low-emotion periods, the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSIt−1) consistently exhibits negative predictive effects across all five models of public behavior. Specifically, the variables Tour Intent, Share, and Review Emotion are statistically significant at the 5% level, with t-values of −2.001, −2.097, and −2.085, respectively. The Engagement and Likes models also show marginal significance, with t-values of −1.834 and −1.788, respectively.

These findings indicate that in emotionally sensitive contexts related to cultural heritage—such as the exposure to major controversies, destruction, or conflict—the public is more susceptible to the negative visual information conveyed by images. Their behavioral intentions and emotional responses are significantly suppressed, reflecting a pattern of “perceptual dominance” and “emotion-led influence”.

Imagery can trigger immediate emotional responses and influence behavioral expressions without requiring complex semantic processing. This emphasizes the critical role of cultural heritage images in shaping public sentiment and behavior during crises of heritage representation.

Furthermore, due to their historical significance and symbolic emotional weight, cultural heritage images can evoke rapid emotional judgments without semantic decoding, thereby directly influencing public dissemination behaviors. In contrast, the main effects of comment sentiment (CSIt−1) are generally insignificant and directionally unstable. This suggests that under emotionally dominant visual contexts, the rational or delayed information embedded in textual comments receives limited public attention. As a result, the marginal explanatory power of text-based sentiment is substantially diminished.

Further analysis of the image-text interaction term (HSIt−1×CSIt−1) reveals a synergy in multimodal emotional transmission. The interaction term is positive across all five behavioral models, with three achieving significance at the 5% level. This suggests that image and textual sentiment may elicit cognitive-emotional resonance53 in high-emotional volatility contexts, thereby deepening the public’s perception of cultural crisis events. This finding suggests that textual sentiment plays an amplifying role in establishing emotional coherence and contributes to a more comprehensive cultural landscape of affect.

Nevertheless, the empirical results demonstrate that even with emotional alignment between modalities, public responses remain primarily driven by images. Textual content fails to establish a consistent emotional mobilization pathway, underscoring the dominant role of images—as high-perceptual-load media—in emotional transmission and behavior shaping during the negative dissemination of cultural heritage events.

In summary, during major public opinion events related to cultural heritage, image-based information emerges as the primary force driving public emotional and behavioral responses, owing to its concreteness, visual impact, and symbolic historical connotations. While textual comments convey cultural value judgments and facilitate cognitive construction, their influence tends to be marginalized in high-emotion contexts due to limitations in attentional resources.

This finding highlights the distinctive emotional guiding role of cultural imagery and offers empirical evidence for optimizing communication strategies in the heritage domain. Specifically, it highlights the need to strengthen image-led multimodal information integration and strategic allocation of public attention within cultural dissemination frameworks.

Discussion

This study employs deep image sentiment recognition techniques to construct the Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) tailored to cultural heritage communication scenarios. Using public behavioral data from social media platforms, we systematically examined how image-based emotional cues influence users’ cultural engagement intentions and affective responses. The study offers three key contributions: theoretical validation, cross-modal interaction mechanisms, and methodological innovation.

First, the study validates the predictive power of the image-based HSI in cultural heritage communication and elucidates the “emotion-induced behavioral transformation” mechanism. Empirical findings indicate that HSI is significantly and negatively associated with users’ tourism intentions, interactive behaviors, and comment sentiments. Furthermore, the lagged effect of HSI reveals a dynamic trajectory of “initial emotional shock followed by a positive recovery”. Specifically, when cultural heritage images convey intense negative emotions—such as site destruction, the disappearance of traditional festivals, or cultural conflict—public responses the following day tend to show reduced willingness to participate and intensified emotional expressions. This aligns with affective decision-making theory, which posits that emotions disrupt short-term judgment. The results underscore that heritage images serve as both esthetic representations and emotionally charged stimuli, shaping cultural identity and decision-making processes.

Second, the study identifies a dual-path emotional mechanism between image and textual modalities in cultural heritage communication. Due to their high perceptual salience and immediacy, emotional images influence audience responses by activating fast-reacting emotional systems and triggering immediate behavioral suppression. In contrast, emotional cues in textual comments rely on semantic interpretation and social context, typically playing a compensatory role when image sentiment is weak or ambiguous. Empirical results suggest that, during high-emotion periods, image and text-based emotional cues exhibit a competitive rather than complementary relationship. The visual channel diminishes the marginal explanatory power of text-based sentiment. This effect is particularly pronounced during heritage crises, reaffirming the dominant role of images as “high cognitive-load media” in emotional transmission, offering practical insights for multimodal content design and attention allocation.

Third, the study demonstrates the feasibility and adaptability of deep learning-based image sentiment recognition in cultural behavior research. The traditional sentiment analysis approaches rely heavily on subjective labels or manual annotations. However, the proposed HSI framework—based on transfer learning and probabilistic sentiment weighting—exhibits higher efficiency and robustness while processing unstructured, stylistically diverse cultural imagery. This methodological advancement enhances the scalability of emotion data construction, offering a generalizable, data-driven toolset for future research in digital cultural communication.

It is important to note that the behavioral variables used in this study are derived primarily from online interaction records on social media platforms. Such data can effectively capture users’ immediate emotional reactions and dissemination behaviors following exposure to cultural heritage imagery, but they may only indirectly reflect deeper offline processes such as tourism decision-making, cultural experience behaviors, or the formation of cultural identity. Future research could therefore integrate heterogeneous data sources—such as survey responses, tourist mobility trajectories, cultural event participation records, mobile LBS data, or official statistics—to systematically examine how online emotional signals translate into offline behavioral outcomes. Experimental or immersive display settings may also be employed to manipulate visual emotional stimuli under controlled conditions, thereby enhancing external validity, behavioral interpretability, and cross-media applicability.

At the data and model level, the original training sample of DeepSent is relatively limited. Although the manually reviewed and semantically filtered validation samples used in this study exhibit strong thematic relevance—and the model’s reliability in cultural heritage contexts has been demonstrated through transfer learning and robustness checks—its broader generalizability across larger-scale and multi-context datasets remains to be fully assessed. Future work may retrain and expand emotion labels on substantially larger cultural heritage image corpora, while also incorporating multimodal features such as video cinematics, vocal prosody, ambient sound, geolocation information, and dynamic user interaction behaviors. Such multimodal integration would help reveal the multi-layered triggering mechanisms of visual emotions in real-world cultural communication settings, enhance the explanatory and predictive power of emotion–behavior models, and strengthen cross-cultural adaptability and generalization performance.

Regarding data sources, although this study incorporates both Xiaohongshu—representing a Chinese cultural–social context—and Instagram—representing a global and highly heterogeneous visual environment—the two platforms cannot fully reflect the diversity of visual expression across different countries and cultural backgrounds. To further improve cross-cultural representativeness and external robustness, future research may incorporate additional mainstream visual platforms from various regions and cultural spheres, such as TikTok, YouTube, Twitter/X, Pinterest, Weibo, and BiliBili, as well as non-social visual materials including news images, museum exhibition records, and institutional archival imagery. Constructing such a more diverse, cross-platform, and cross-cultural visual corpus would enable a more systematic assessment of the consistency and generalizability of the proposed sentiment index across different media environments and cultural contexts.

Taken together, the proposed Heritage Sentiment Index (HSI) not only broadens the measurable dimensions of cultural-heritage communication effectiveness but also demonstrates that visual emotional cues exert a significant and predictable influence on public behavioral responses. This extends theoretical understanding of multimodal emotional mechanisms in heritage communication. The study highlights that emotional content embedded in cultural-heritage images functions not merely as an esthetic or communicative attribute but plays a central role in meaning-making, emotional appraisal, and behavioral motivation among the public.

Against the backdrop of deepening “culture–tourism integration” and “smart cultural governance,” image-based emotion recognition technologies hold substantial practical potential. They can support intelligent management of heritage sites, tourism demand monitoring, cultural-risk early warning, and real-time public-emotion assessment during major cultural events. As cross-platform, cross-cultural, and multimodal recognition systems continue to advance, such technologies may become key analytical tools for heritage activation, tourism marketing optimization, and public cultural-communication governance, offering higher-resolution evidence for sustainable heritage dissemination and social-emotion management.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. The raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Karl, M., Kock, F., Ritchie, B. W. & Gauss, J. Affective forecasting and travel decision-making: An investigation in times of a pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 87, 103139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103139 (2021).

Naseer, K. et al. Travel behaviour prediction amid COVID-19 underlaying situational awareness theory and health belief model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 41, 3318–3328 (2022).

Neidhardt, J., Rümmele, N. & Werthner, H. Predicting happiness: user interactions and sentiment analysis in an online travel forum. Inf. Technol. Tour. 17, 101–119 (2017).

Fu, X., Liu, X. & Li, Z. Catching eyes of social media wanderers: How pictorial and textual cues in visitor-generated content shape users’ cognitive-affective psychology. Tour. Manag. 100, 104815 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Understanding the influence of user-generated content on tourist loyalty behavior in a cultural World Heritage Site. Tour. Recreat. Res. 48, 173–187 (2023).

Su, D. N., Nguyen, N. A. N., Nguyen, Q. N. T. & Tran, T. P. The link between travel motivation and satisfaction towards a heritage destination: The role of visitor engagement, visitor experience and heritage destination image. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 34, 100634 (2020).

Cominelli, F. & Greffe, X. Intangible cultural heritage: Safeguarding for creativity. City, Cult. Soc. 3, 245–250 (2012).

Kätsyri, J., Ravaja, N. & Salminen, M. Aesthetic images modulate emotional responses to reading news messages on a small screen: A psychophysiological investigation. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 70, 72–87 (2012).

Birjali, M., Kasri, M. & Beni-Hssane, A. A comprehensive survey on sentiment analysis: Approaches, challenges and trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 226, 107134 (2021).

Zhu, L., Zhu, Z., Zhang, C., Xu, Y. & Kong, X. Multimodal sentiment analysis based on fusion methods: A survey. Inf. Fusion 95, 306–325 (2023).

Fiorucci, M. et al. Machine learning for cultural heritage: a survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 133, 102–108 (2020).

Gîrbacia, F. An Analysis of Research Trends for Using Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage. Electronics 13, 3738 (2024).

Furini, M., Mandreoli, F., Martoglia, R. & Montangero, M. A predictive method to improve the effectiveness of twitter communication in a cultural heritage scenario. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 15, 1–18 (2022).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Song, J., Gao, S., Zhu, Y. & Ma, C. A survey of remote sensing image classification based on CNNs. Big Earth Data 3, 232–254 (2019).

Zou, Z., Zhao, X., Zhao, P., Qi, F. & Wang, N. CNN-based statistics and location estimation of missing components in routine inspection of historic buildings. J. Cult. Herit. 38, 221–230 (2019).

Dufitimana, E. et al. Measuring urban socio-economic disparities in the global south from space using convolutional neural network: the case of the City of Kigali, Rwanda. GeoJournal 89, 107 (2024).

You, Q., Luo, J., Jin, H. & Yang, J. Robust image sentiment analysis using progressively trained and domain transferred deep networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 29. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v29i1.9179. (2015).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; pp 2818–2826 (2016).

Sam, S. M., Kamardin, K., Sjarif, N. N. A. & Mohamed, N. Offline signature verification using deep learning convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures GoogLeNet inception-v1 and inception-v3. Procedia Comput. Sci. 161, 475–483 (2019).

Yang, L., Hanneke, S. & Carbonell, J. A theory of transfer learning with applications to active learning. Mach. Learn. 90, 161–189 (2013).

Loughran, T. & McDonald, B. When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. J. Financ. 66, 35–65 (2011).

Barrett, L. F. Categories and their role in the science of emotion. Psychol. Inq. 28, 20–26 (2017).

Tetlock, P. C. Giving content to investor sentiment: The role of media in the stock market. J. Financ. 62, 1139–1168 (2007).

Amir, A., Farach, M., Idury, R. M., Lapoutre, J. A. & Schaffer, A. A. Improved dynamic dictionary matching. Inf. Comput. 119, 258–282 (1995).

Song, M. Chambers, T. Text mining with the Stanford CoreNLP. In Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods And Practice, Springer; pp 215–234 (2014).

Zhang, S. et al. Deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition from audio, visual, and text modalities: A systematic review of recent advancements and future prospects. Expert Syst. Appl. 237, 121692 (2024).

Ezzameli, K. & Mahersia, H. Emotion recognition from unimodal to multimodal analysis: A review. Inf. Fusion 99, 101847 (2023).

Socher, R. et al. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods In Natural Language Processing; pp 1631–1642 (2013).

Dixon, W. J. & Yuen, K. K. Trimming and winsorization: A review. Stat. Hefte 15, 157–170 (1974).

Wang, Y. et al. A systematic review on affective computing: Emotion models, databases, and recent advances. Inf. Fusion 83, 19–52 (2022).

Kratzwald, B., Ilić, S., Kraus, M., Feuerriegel, S. & Prendinger, H. Deep learning for affective computing: Text-based emotion recognition in decision support. Decis. Support Syst. 115, 24–35 (2018).

Lucas, J. The forgotten movement to reclaim Africa’s stolen art. New Yorker, 14 (2022).

Rivera Mindt, M., Byrd, D., Saez, P. & Manly, J. Increasing culturally competent neuropsychological services for ethnic minority populations: A call to action. Clin. Neuropsychol. 24, 429–453 (2010).

Kucukergin, K. G. & Uygur, S. M. Are emotions contagious? Developing a destination social servicescape model. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 14, 100386 (2019).

Stamkou, E., Keltner, D., Corona, R., Aksoy, E. & Cowen, A. S. Emotional palette: a computational mapping of aesthetic experiences evoked by visual art. Sci. Rep. 14, 19932 (2024).

Lin, R. et al. Visualized Emotion Ontology: a model for representing visual cues of emotions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 18, 101–113 (2018).

Uhrig, M. K. et al. Emotion elicitation: A comparison of pictures and films. Front. Psychol. 7, 180 (2016).

Lindquist, K. A., Jackson, J. C., Leshin, J., Satpute, A. B. & Gendron, M. The cultural evolution of emotion. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 669–681 (2022).

Masuda, T. Culture and attention: Recent empirical findings and new directions in cultural psychology. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 11, e12363 (2017).

Karlsson, N., Loewenstein, G. & Seppi, D. The ostrich effect: Selective attention to information. J. Risk Uncertain. 38, 95–115 (2009).

King, L. M. & Halpenny, E. A. Communicating the World Heritage brand: visitor awareness of UNESCO’s World Heritage symbol and the implications for sites, stakeholders and sustainable management. J. Sustain. Tour. 22, 768–786 (2014).

Newey, W. K. & West, K. D. A Simple, Positive Semi-definite, Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelationconsistent Covariance Matrix, (1986).

Aiken, L. S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage, (1991).

Matsumoto, D. & Hwang, H. S. Culture and emotion: The integration of biological and cultural contributions. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 43, 91–118 (2012).

Maki, R. H. Predicting performance on text: Delayed versus immediate predictions and tests. Mem. Cogn. 26, 959–964 (1998).

Li, Q., Huang, Z. J. & Christianson, K. Visual attention toward tourism photographs with text: An eye-tracking study. Tour. Manag. 54, 243–258 (2016).

Bakar, M. H. A., Desa, M. A. M. & Mustafa, M. Attributes for image content that attract consumers’ attention to advertisements. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 195, 309–314 (2015).

Lenski, S. & Großschedl, J. Emotional design pictures: Pleasant but too weak to evoke arousal and attract attention? Front. Psychol. 13, 966287 (2023).

Kaplan, E. A. Global trauma and public feelings: Viewing images of catastrophe. Consum., Mark. Cult. 11, 3–24 (2008).

Meek, A. Trauma and Media: Theories, Histories, and Images; Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203863190. (2011).

Filip, A. M. & Pochea, M. M. Intentional and spurious herding behavior: A sentiment driven analysis. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 38, 100810 (2023).

Bufquin, D., Park, J.-Y., Back, R. M., Nutta, M. W. & Zhang, T. Effects of hotel website photographs and length of textual descriptions on viewers’ emotions and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 87, 102378 (2020).

Orth, U. et al. Effect size guidelines for cross-lagged effects. Psychol. Methods 29, 421 (2024).

Acknowledgements