Abstract

Soft capping is widely used to protect earthen archaeological sites, yet its long-term stability mechanisms remain unclear. This study examines how slope aspect and elevation shape soil and vegetation patterns in a Trifolium repens soft-capping system at Damojiao Hill. Field surveys quantified vegetation cover and density, soil physicochemical properties, and nutrient distribution across topographic gradients. Results show that slope aspect controls horizontal heterogeneity of vegetation and soil, while elevation regulates systematic spatial differentiation of water and heat. Northern and eastern slopes exhibited higher vegetation cover and soil organic matter with lower nutrient depletion, whereas southern and western slopes showed sparse cover, phosphorus and potassium deficits, and increased bulk density. These patterns reflect enhanced nutrient leaching on north-facing slopes and accelerated organic-matter mineralization on south-facing slopes. Overall, the study identifies topography as a key driver of spatial heterogeneity, providing a diagnostic basis for site-specific assessment of soft-capping systems in humid regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amidst the intensifying challenges of global climate change, the conservation of open-air earthen archaeological sites confronts multiple challenges. Soft capping has emerged as an environmentally sustainable and climate-adaptive conservation strategy, offering surface protection for exposed architectural heritage through the synergistic interaction of vegetation and soil1. Originating from conservation practices applied to the remains of medieval castles and churches in the United Kingdom2, this technique has since been adopted across various regions of the Eurasian continent3,4,5. The core mechanism of soft capping involves the integration of vegetation with breathable materials to modulate surface temperature and humidity at heritage sites, thereby mitigating erosive processes such as thermal expansion and freeze-thaw cycles6. This low-intervention approach improves the stability of surface soils while simultaneously addressing the dual objectives of conservation and visual presentation7. In terms of application to diverse heritage typologies, masonry structures often incorporate native vegetation in conjunction with consolidation layers—comprising composite materials such as soil, slate fragments, and lime—as alternatives to rigid capping systems8,9; whereas for earthen sites, the combination of vegetation and structural support layers serves to reduce natural erosion of walls and slopes10. This ecologically driven methodology represents a strategic shift in the conservation of earthen sites under changing climatic conditions, moving away from traditional rigid interventions toward dynamic and adaptive conservation models.

Although soft capping demonstrates proven protective efficacy across diverse climatic regimes, its inherent dynamism may experience degradation due to climate variability, ecological succession, or inadequate management, thereby directly compromising the safety and visual integrity of earthen sites6. To mitigate these risks, existing research has evolved along two principal trajectories: maintenance practices and mechanistic studies. On one hand, the periodic renewal of vegetation and consolidation layers is employed to preserve the functional stability of soft capping systems8; on the other hand, studies have sought to elucidate the adaptive limitations of soft capping under complex environmental conditions11,12. Research across various climatic zones reveals substantial regional differentiation. In arid and semi-arid regions, the interaction between biological soil crusts—particularly mosses—and underlying soil has been shown to enhance the structural integrity of heritage sites13. Consistent with artificial rainfall and runoff quantification experiments as well as CFD-based microenvironment simulations showing slope-aspect–driven hydrological divergence14. Morphological and mechanical stress analyses have demonstrated that soft capping systems composed of native vegetation and soil can effectively reinforce earthen structures on sloped terrains15 found that the physical structure of vegetation—specifically the overhang width—is the key determinant of drainage efficiency, while orientation indirectly regulates water management mechanisms by shaping the growth morphology of vegetation. Case studies from northwestern China further validate that such vegetation can regulate hydrothermal conditions, thereby suppressing weathering and erosion of vertical or inclined structures16. Conversely, studies conducted in Turkey have identified adverse effects; soft capping systems dominated by species such as Poa bulbosa and Stipa capillata were found to exacerbate erosion during rainfall events, emphasizing the critical need for integrated research that aligns vegetation selection with site-specific morphological and topographical characteristics3. In humid climatic zones, distinct patterns have emerged. For instance, case studies in southern China report that species such as Zoysia japonica and Sedum sarmentosum can induce a summer cooling effect within the top 6–8 cm of soil through their stem-leaf layers1. However, research at the Sanxingdui site suggests that the deep-rooting behavior of herbaceous plants may loosen the soil structure, undermining the long-term stability of soft capping systems17. Moreover, algae and lichens prevalent in humid environments are known to secrete organic acids, which can accelerate mineral dissolution and biocorrosion processes1,18,19. These findings collectively underscore that soft capping functions as a dynamic and context-dependent system, with its efficacy shaped by interactions among vegetation type, consolidation material properties, and topographic as well as hydrothermal conditions. Nonetheless, for specific cases in humid climates—particularly earthen sites such as the Liangzhu Archaeological Site, characterized by regular morphological and topographic features—a systematic understanding of soft capping degradation mechanisms remains lacking. This gap hampers the development of precisely targeted and adaptive conservation technologies.

As a representative earthen site located in the humid climatic zone of southern China, the Liangzhu Site was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2019, followed by the commencement of a heritage park development project. In conjunction with this initiative, a soft capping system—primarily consisting of a single species, Trifolium repens. L.—was implemented in the core palace and city wall zones. The selection of this species was based on its nitrogen-fixing capacity as a perennial legume20, its uniform morphology conducive to preserving the surface contours of the site, and its ability to fulfill the combined requirements of heritage conservation, ecological functionality, and landscape aesthetics21. However, after six years of application, the originally monocultural soft capping system has transitioned into a mixed vegetation community22,23, accompanied by emerging issues such as vegetation degradation, weed encroachment, localized erosion, and soil layer thinning. Understanding the underlying degradation mechanisms has thus become critical for optimizing the technical parameters of the system. Existing ecological research has systematically demonstrated the influence of topographic gradients and hydrothermal conditions on the interrelationship between soil properties and vegetation dynamics24,25, and the environmental factors influencing the T. repens. The stolons of T. repens spread rapidly to form a dense ground cover, effectively shielding the soil surface and reducing direct raindrop impact. Its well-developed fibrous root system forms an extensive subsurface network, enhancing topsoil stability and mitigating erosion. Existing research from the Mediterranean region has demonstrated that the introduction of Trifolium repens significantly reduces surface runoff on slopes, while its low maintenance requirements make it particularly suitable for application in soft-capping systems26. And the potential impact of soil nutrient availability on the greening of the archaeological site27. These studies offer a methodological framework for analyzing the degradation processes of soft capping systems. However, there is a lack of research on sites that are morphologically complex and where soft capping communities are transitioning. This study, employing a “slope aspect-slope position” grid framework, investigates the growth status of T. repens and the spatial heterogeneity of soil physicochemical properties across different slope aspects and slope positions within the Liangzhu soft capping system. This is an adaptive management framework, whose core lies in formulating differentiated functional strategies in response to the micro-environmental variations induced by slope orientation, thereby enabling the long-term sustainable conservation of soft-capping systems10,28. The objective is to evaluate the extent and mechanisms of degradation, thereby providing empirical support for scientifically informed vegetation renewal in the forthcoming maintenance cycle. This approach facilitates a strategic transition in earthen site conservation—from passive remediation to proactive risk prevention—and supplies both a data-driven foundation and practical guidance for developing sustainable ecological protection strategies applicable to similar heritage sites worldwide.

Method

Case selection

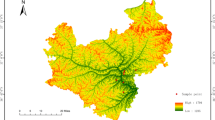

On July 6, 2019, the Liangzhu Site was inscribed on the World Heritage List. It has been widely recognized as a model of early urban civilization and an outstanding representative of prehistoric rice-based culture in China, with a history spanning over 5000 years29. The site is situated on the piedmont riverine plain at the eastern terminus of the Tianmu Mountains, within the Yangtze River Delta region in southeastern China. Administratively, it falls under the jurisdiction of Yuhang District, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province (Fig. 1). Geographically, the site is located within the monsoon climate zone at the southern edge of the northern subtropics, characterized by four distinct seasons, ample sunshine, and abundant precipitation. The region experiences a generally warm and humid climate, with rainfall and temperature peaking during the spring and summer months, while light and warmth are well-matched during autumn and winter. The annual average precipitation is between 1150 and 1550 mm, with more than 60% of the total rainfall occurring between May and September30. These climatic conditions not only provide a favorable natural foundation for the emergence of prehistoric rice agriculture but also pose significant challenges for long-term preservation31,32. Wind speed and precipitation exhibit no significant spatial variation within the small-scale tableland environment of the study area. Solar radiation is the key driver of aspect-induced variation. Based on the DEM data, we computed the mean slopes of the south–north and east–west facing hillslopes, which are 16.7° and 21.8°, respectively. Using a terrain-based slope radiation correction model33,34,35, we further estimated that the south-facing slope receives the highest solar radiation (14.893 MJ m−² day−¹ ≈ 172.3 W m−²), the north-facing slope the lowest (10.796 MJ m−² day−¹ ≈ 124.9 W m−²), with the east–west slopes falling in between. This quantifies the aspect-driven heterogeneity in solar exposure and provides essential environmental context for subsequent analyses (Fig. 2).

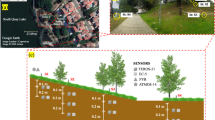

a Schematic Diagram of the Initial T. repens-Dominated Soft Capping Structure; b Photograph of Existing T. repens; c Vigorous Growth of T. repens on the Eastern Slope; d Invasive Weed Species; e Localized Vegetation Degradation on the Southern Slope; f Water Accumulation at the Lower Position of the Northern Slope. Author’s photo.

The primary heritage elements of the Liangzhu Site are earthen remains, encompassing large-scale and structurally fragile features such as city walls and palace platforms36, which are preserved and exhibited in situ. Mojiaoshan constitutes the core area of the Liangzhu Site, comprising three palace platforms—Damojiao Hill, Xiaomojiao Hill, and Wugui Hill—as well as 35 residential platforms, highlighting its function as the political center of Liangzhu culture. Among these, Damojiao Hill is the largest and tallest, representing a rectangular, artificially constructed earthen platform measuring 180 m from east to west, 110 m from north to south, and about 6 m in relative height37.

To better understand the application context and current status of soft-capping techniques at the Liangzhu site, the research team conducted semi-structured interviews with the Liangzhu Heritage Management Committee, gathering information on conservation strategies and technical implementation details. The entire interview process was documented (see appendix). Key insights are summarized as follows. In 2019, with the initiation of the Liangzhu Site Park project, the conservation team implemented a soft capping system comprising T. repens and a consolidated soil layer. This intervention served two primary objectives: first, to delineate the boundaries of the palace and city wall remains, thereby enhancing visitors’ perception of their distinction from other site features; and second, to mitigate the erosive effects of wind, rainfall, and solar radiation, thus realizing a low-intervention, ecologically based conservation approach10.

During our team’s on-site investigation of the Liangzhu Ancient City ruins, it was found that after six years of application, the soft capping system has begun to exhibit limitations in terms of adaptability, with pronounced variation across different slope aspects and slope positions. The degradation is manifested primarily in three respects: (1) Degradation and incomplete coverage of the overlying soil layer. The once continuous Trifolium repens cover has developed visible discontinuities, and in some areas the soft capping shows exposed soil, surface cracking, and crusting. These conditions reveal a compromised soil structure. (2) Vegetation community succession and invasion. The originally monocultural white-clover is undergoing a transition toward a mixed community type. Several aggressively colonizing native species (such as Erigeron acer, Alternanthera philoxeroides, and Aeschynomene indica) have progressively assumed dominance, creating a competitive replacement effect. This has weakened the growth of Trifolium repens, reduced overall spatial uniformity. (3) Intensification of surface runoff and waterlogging. Pronounced runoff channels have formed on the soft-cover surface, and persistent water accumulation has been observed at the northern foot of the site. This indicates that hydrological imbalance — driven by differences in slope aspect — has become a major accelerating force of degradation.

The issues mentioned above have also been confirmed by the management of the governing committee. Relevant personnel clarified that the primary objective of soft-cover maintenance over the past five years has been to ensure that the soil remains covered and that the visual perception of the overall landscape is not affected. Overly tall weeds, such as Solidago decurrens Lour., are typically removed, but no specific control measures have been implemented for other types of vegetation. Officially, no soil or vegetation data has been accumulated over the past five years. Additionally, the daily vegetation maintenance is carried out by the park authorities (which is an agency under the Liangzhu Management Committee), but there is no specific methodology in place. Collectively, these issues have adversely affected both the conservation integrity and the visual presentation of the site.

Data collection and preprocessing

Field sampling of T. repens and soil within the soft capping system on Damojiao Hill was carried out in the spring of 2025. Figure 3 illustrate the framework of this study.

Inspired by22,23, a grid-based quadrat survey method was utilized, segmenting the study area into four slope aspects: east, west, south, and north. Each slope aspect was further subdivided horizontally into three zones—designated as A, B, and C—and each zone was stratified vertically into three elevation segments: upper, middle, and lower (Fig. 4a). The T. repens survey concentrated on analyzing population distribution patterns and growth indicators under varying site conditions (Fig. 4b, c). Key parameters recorded included habitat and surface characteristics, percent cover, frequency, density, and stolon length (both maximum and minimum values). To ensure the protection of underlying archaeological features, soil samples were collected exclusively from the surface layer (0–20 cm). All sampling protocols were implemented under the official authorization of the Liangzhu Site Administration Committee, with strict adherence to archaeological conservation ethics and regulatory compliance frameworks.

To ensure scientific validity, each sampling unit followed a standardized procedure. In each of the 30 designated area, 5 soil samples were taken randomly using a soil ring knife. The sampling steps included clearing the vegetation and litter, documenting the surface appearance, taking photographs, and averaging the data to minimize experimental error. The primary physicochemical properties analyzed in the laboratory included the soil pH, bulk density, available potassium (K), available phosphorus (P), total nitrogen (N), and organic matter content. Bulk density was measured using the soil ring knife method. pH was determined directly using the electrode method in a water extract of the soil. The organic matter content was analyzed via K dichromate oxidation-colorimetry. Available potassium and phosphorus were measured using spectrophotometry, whereas total nitrogen was determined using the Kjeldahl method. All measured data were averaged to reduce experimental variance.

Throughout the sampling process, all the soil cores extracted with the ring knife remained intact, with no missing or repeated samples (Fig. 4d, e). The drying temperature and duration were standardized to prevent data deviations. The analytical results were cross-validated with in situ soil profile characteristics, such as color and texture, to ensure data reliability. In total, 5 soil samples from each designated area are combined into one composite sample and submitted to the laboratory for testing. 30 T. repens vegetation quadrats were collected across the four slope aspects and three elevation segments of Damojaoshan.

Additionally, we conducted a series of correlation analyses based on slope gradient, slope aspect, soil physicochemical properties, as well as the height, coverage, and density of white clover (Trifolium repens). We further constructed a regression-type Random Forest model with Trifolium repens data as the dependent variable. The model was configured with 1000 decision trees (ntree = 1000), and the number of candidate variables at each split was set to the default value (mtry = √p). The splitting criterion was the minimization of Mean Squared Error (MSE). Model robustness was evaluated using the out-of-bag (OOB) error, while variable importance was quantified by the percentage increase in MSE (%IncMSE), allowing the identification of key environmental factors influencing Trifolium repens growth. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.3) using the randomForest package.

Results

Analysis of the slope aspect effects on T. repens L. growth characteristics

To investigate the effects of slope aspect on the growth characteristics of T. repens, this study conducted a systematic survey and comparative analysis of its coverage, density (abundance), and plant height across the east, south, west, and north slopes (Fig. 5). The results indicated the following:

In terms of coverage, the eastern slope presented the highest value (about 52%), which was significantly greater than those of the other aspects (P < 0.05), whereas the southern slope presented the lowest coverage (about 18%). In terms of density, the east slope presented the highest individual density (about 155 ind/m2), followed by the north slope (about 135 ind/m2), with both significantly exceeding the values observed on the west and south slopes (about 40–50 ind/m2) (P < 0.05).

For plant height, the mean height of individuals on the east slope was the greatest (about 22 cm), which was significantly greater than that on the west slope (about 8 cm) (P < 0.05). Although the average heights on the southern and northern slopes were slightly lower than those on the eastern slope, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Slope- aspect driven adaptation strategies for soft capping conservation

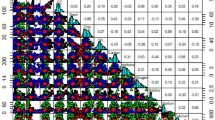

Figure 6 presents the correlation analysis of soil physicochemical properties (0–20 cm) of the soft capping system across different slope aspects. On the northern slope, potassium (K) and phosphorus (P) were significantly positively correlated, whereas nitrogen (N) was significantly positively correlated with organic matter. On the southern slope, K was significantly negatively correlated with both N and organic matter, whereas N and organic matter remained significantly positively correlated. On the east slope, soil pH was significantly positively correlated with K, and N was significantly positively correlated with organic matter. On the west slope, N and organic matter were significantly positively correlated, whereas bulk density was significantly negatively correlated with P.

These results indicate substantial variations in the correlations among soil physicochemical properties across different slope aspects. Notably, nitrogen and organic matter consistently demonstrated positive correlations across all slopes, suggesting that such patterns may be influenced by the combined effects of topography, solar radiation, moisture, and vegetation.

Specifically, Fig. 7a presents the analysis of soil physicochemical properties at different elevations on the east slope. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) results indicate that at elevations of 2.1–4.0 m, the organic matter content was relatively high at 21.10 g/kg, whereas the variation in the other indicators was minimal. Therefore, elevation does not have a significant effect on the soil physicochemical properties of the east slope, and the properties are relatively uniform across different elevations.

Figure 7b shows the results of the soil physicochemical property analysis at different elevations on the west slope. The ANOVA results revealed that at elevations of 2.1–4.0 m, the organic matter content reached 24.65 g/kg, with the other indicators showing minimal differences. Thus, similar to the east slope, elevation does not significantly affect the soil physicochemical properties on the west slope, which also demonstrates relative uniformity across elevations.

In contrast, the ANOVA results for the north slope (Fig. 7c) indicate that phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) contents exhibit significant variation with elevation, while other elements remain unaffected. At elevations ranging from 0 to 2.0 m, the concentrations of K and P were 14.90 g/kg and 0.50 g/kg, respectively—both significantly lower than those observed at higher elevations. These findings demonstrate that elevation exerts a significant influence on the P and K contents within the soft capping soil of the north slope, with higher elevations corresponding to elevated levels of these elements.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) results (Fig. 7d) indicate that on the southern slope, there are significant differences in phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N) contents across different elevations, whereas potassium (K), organic matter, and pH do not significantly vary. At an elevation of 0–2.0 m, the P content was 0.40 g/kg, which was significantly lower than that at other elevations. At an elevation of 2.1–4.0 m, the N content was 1.57 g/kg, which was significantly greater than that at other elevations, and the organic matter content was 24.23 g/kg, which was relatively high but not significantly different. Therefore, elevation had a significant effect on the P and N contents in the soft capping soil of the southern slope, with higher elevations resulting in higher P and N levels, whereas at 0.3–1.6 m, both the P and N contents were lower.

As shown in the Fig. 8, the correlation analysis of the soil physicochemical properties at different slope positions revealed that the nitrogen (N) content was significantly positively correlated with the organic matter content at all slope positions. At slopes of 4.1–6.0 m, the potassium (K) content was significantly negatively correlated with organic matter and N, and pH was significantly negatively correlated with phosphorus (P). At slope positions of 2.1–4.0 m, P was significantly positively correlated with both N and organic matter. At slope positions of 0–2.0 m, K was significantly negatively correlated with organic matter, and pH was significantly negatively correlated with both organic matter and N. When the effects of slope aspect and elevation were disregarded, K was significantly negatively correlated with both organic matter and N and significantly positively correlated with pH, whereas N was significantly positively correlated with P. Therefore, the correlations among soil physicochemical properties at different slope positions vary significantly, and these differences may be related to factors such as soil formation processes, biological activity, and water movement.

Figure 9 analyzes soil characteristics across slope positions and directions. At 4.1–6.0 m (Fig. 9a), organic matter, bulk density, and N showed no significant differences. K was highest on the east slope (18.35 g/kg, p < 0.05) and lowest on the south (15.23 g/kg) and north (15.10 g/kg) slopes. P was greatest on the west slope (0.79 g/kg) and lowest on the south slope (0.51 g/kg). pH was higher on the east (6.27) and south (6.22) slopes than on the west (4.95) and north (5.22). At 2.1–4.0 m (Fig. 9b), bulk density showed no difference. K remained highest on the east (18.10 g/kg) and lowest on the north slope (15.47 g/kg). P was highest on the west slope (0.79 g/kg) and lowest on the south slope (0.55 g/kg). Organic matter was greatest on the west slope (24.65 g/kg). pH was highest on east (5.99) and south (5.86) slopes. N was higher on the west slope (1.61 g/kg) than the south (1.22 g/kg). Southern slope properties were generally lower.

At 0–2.0 m (Fig. 9c), K was lowest on the north slope (14.90 g/kg). P was higher on east (0.61 g/kg) and west (0.63 g/kg) slopes than the south (0.40 g/kg). Organic matter was greater on the north slope (22.33 g/kg) than the east (17.00 g/kg). pH was higher on south (5.81) and east (5.98) slopes. N was lower on the east slope (1.16 g/kg) than north (1.40 g/kg) and west (1.41 g/kg). Figure 9d summarizes directional trends: K was highest on east (18.13 g/kg) and lowest on north (15.30 g/kg). P was highest on west (0.73 g/kg) and lowest on south (0.49 g/kg). Organic matter was lower on east (18.77 g/kg). pH was higher on south (5.97) and east (6.08) slopes. N was higher on west (1.50 g/kg). At 0–2.0 m, the west slope had higher P, N, and organic matter, while the south slope had the lowest P and K.

Correlation analysis of environmental factors (slope aspect and position) and soil physicochemical properties of T. repens L. growth characteristics

To systematically evaluate the effects of slope aspect- and position-driven soil physicochemical properties on the growth characteristics of T. repens L.(white clover) in the Damojiashan soft capping system, this study employed multivariate statistical approaches—including random-forest modeling, redundancy analysis (RDA), and Pearson correlation analysis—to elucidate their driving mechanisms from multiple dimensions.

Random forest analysis (Fig. 10) revealed slope aspect as the primary determinant of plant density, with the highest mean squared error (MSE) increase rate (~20%, P < 0.05), which significantly surpassed that of the other variables. Soil potassium (K), phosphorus (P), and bulk density (BD) emerged as secondary drivers, indicating substantial regulatory effects of soil nutrient availability and structural properties on individual clover distribution. In contrast, pH, total nitrogen (N), and slope position exerted relatively weak influences, whereas soil organic matter (SOM) made a negative contribution, suggesting minimal relevance to this metric.

For coverage, slope aspect remained the dominant factor (MSE increase rate ~12%, P < 0.05), followed by K and P, implying that light conditions and nutrient supply collectively govern the ground-covering capacity. Other variables (e.g., pH, BD, N) had low contributions, with slope position and SOM maintaining negative correlations. Conversely, plant height exhibited limited sensitivity to environmental factors, with all variables displaying low and negative MSE increases. Notably, SOM, P, and pH had the weakest contributions, suggesting that plant height may be governed by nonenvironmental factors or constrained by limited variability under current site conditions.

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis further corroborated the aforementioned findings: percent coverage exhibited a significant negative correlation with slope aspect and a positive correlation with K and P levels, indicating a high sensitivity to both light availability and nutrient conditions. In contrast, plant density and height demonstrated generally weak correlations with environmental variables (|r | < 0.2), suggesting either greater intrinsic stability or limited effectiveness in representing community-level responses of T. repens. (Fig. 11).

An integrated analysis employing Random Forest and redundancy analysis (RDA) (Fig. 12) identified slope aspect, total potassium, and soil bulk density (BD) as the primary factors influencing the spatial distribution and community structure of T. repens. The RDA results indicated that soil physicochemical properties accounted for 85.1% of the variation in growth characteristics. Specifically, coverage and plant height were positively correlated with BD and K, and negatively correlated with total nitrogen and soil organic carbon. These findings suggest that moderate BD enhances water and nutrient retention, thereby supporting root development, while elevated potassium levels promote photosynthesis and increase stress resistance. In contrast, excessive concentrations of nitrogen and organic carbon may stimulate microbial activity and intensify competition for nutrients, thereby indirectly inhibiting aboveground plant growth.

The density demonstrated a preference for slightly acidic to neutral environments, which were coregulated by pH, total nitrogen, and organic carbon. This relationship likely reflects the synergistic effects of enhanced soil structure and microbial activity, which improve seedling establishment success. The framework of the main results has been shown in Fig. 13.

Discussion

Although soft capping systems have been widely adopted for the protection of earthen sites in humid regions1,2,4,5, their long-term behavior—particularly for monoculture systems such as T. repens—has not been sufficiently evaluated, especially under terrain-differentiated microenvironments. Based on a field-based assessment at Damojiao Hill, this study identifies slope aspect and elevation as influential topographic variables shaping the spatial coupling between vegetation performance and soil conditions. Beyond detecting notable signs of system degradation after six years, our results suggest that an imbalance in light–water stresses associated with slope orientation may play an important role in the observed patterns. While the north-facing slopes exhibited relatively stable vegetation and soil conditions, the west- and south-facing slopes showed concurrent declines in vegetation cover and nutrient status under stronger radiation and photo-thermal stress. These findings indicate plausible mechanisms but do not allow firm causal attribution without controlled experiments (Table 1).

Our spatial analyses further indicate that vegetation–soil interactions contribute to stabilizing earthen sites1,10,23, and that aspect-related microclimatic variation corresponds to measurable differences in vegetation cover, soil organic matter, and nutrient profiles. North- and east-facing slopes generally exhibited higher T. repens density and soil organic matter, whereas south- and west-facing slopes displayed lower cover, nutrient depletion (e.g., P and K), and higher bulk density. Elevation-driven differences in moisture redistribution were also evident in the stratification of nutrient profiles. Field observations of wet–dry cycling, leaching, localized acidification, and bryophyte-associated microhabitats provide plausible explanations for these patterns. However, these processes were not tested in a controlled setting, and therefore remain interpretive rather than conclusive.

In the context of humid environments, the results suggest that topographic differentiation may be a first-order environmental factor influencing soil moisture, nutrient dynamics, and vegetation performance. Importantly, these observations appear to operate independently of the specific plant species used, indicating that terrain-induced microclimates may be more fundamental than species traits in shaping long-term capping outcomes. Nevertheless, these inferences are based on correlative evidence and should be viewed as preliminary until experimentally validated.

For sites where T. repens cannot be used, the broader relevance of this study lies primarily in its methodological approach—linking microtopographic variation with soft capping performance—rather than in endorsing any specific vegetation solution. Although our observations imply that functional matching between plant traits and microenvironment may be important, this remains a hypothesis that requires targeted experiments for verification. Accordingly, the implications drawn here should be interpreted as diagnostic insights rather than as prescriptive management guidelines.

Given the observational nature of this study, detailed management recommendations cannot be empirically supported at this stage. For this reason, only general directions informed by field evidence are outlined. First, the pronounced aspect heterogeneity underscores the need for site-specific assessments of soil–vegetation conditions. Second, the potential alignment between plant functional attributes and slope microclimates should be treated as a subject for future experimental testing rather than a finalized management approach. Third, the variation in hydrological–thermal conditions observed across slopes highlights the value of post-implementation monitoring38, particularly for detecting early signs of degradation on slopes already exhibiting low vegetation cover or nutrient decline. These points should be regarded as conceptual rather than operational.

A follow-up inspection in October 2025 further revealed rapid replacement of T. repens by local opportunistic species, forming a naturally assembled mixed community within six months. While this observation reinforces the sensitivity of soft capping systems to slope-driven microclimatic pressures, it should not be taken as evidence that mixed communities are preferable. Rather, it illustrates that monoculture systems in humid climates may be inherently dynamic and difficult to maintain without substantial intervention. The ecological implications—both positive and negative—remain uncertain and require controlled comparative research.

In light of these findings, a number of tentative considerations are proposed, not as prescriptive strategies but as potential directions for future experimental and management-oriented studies. For instance, slope-specific interventions (e.g., ameliorating soil acidity on north-facing slopes or mitigating moisture stress on south-facing slopes), exploring functionally complementary plant groups, and establishing more refined monitoring systems may represent productive avenues for investigation. However, these possibilities emerge from observed patterns rather than proven causal mechanisms, and they require rigorous testing before being adopted in practice.

This study also acknowledges several limitations, including the absence of quantitative analysis of vegetation diversity across terrace zones, the lack of direct measurement of root impacts on soil structural integrity, and potential underestimation of multi-year climatic extremes. Future research should integrate minirhizotron imaging and long-term monitoring to develop a more comprehensive model of plant–soil–site interactions. The natural succession observed at the site may also serve as an “unmanaged scenario” for comparison with maintained systems, providing a basis for identifying ecological thresholds, performance boundaries, and long-term trajectories of different soft capping configurations.

Overall, the present findings contribute primarily to understanding the diagnostic role of microtopography in shaping soft capping performance. While they provide useful context for considering slope-aware management, they do not yet justify detailed operational strategies. Future experiments, particularly controlled trials, will be essential to determine whether the slope aspect–function relationships observed here can be translated into reliable, evidence-based conservation practices

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Jiang, X., Yeo, S. Y. & Galli, B. The potential of applying soft capping approach on earthen and masonry built heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 73, 158–171 (2025).

Guo, Q. et al. Key issues and research progress on the deterioration processes and protection technology of earthen sites under multi - field coupling. Coatings 12, 1677 (2022).

Miller, N. F. Historic landscape and site preservation at Gordion, Turkey: an archaeobotanist’s perspective. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot 28, 018–0689 - 4 (2019).

Caneva, G., Hosseini, Z. & Bartoli, F. Risk, hazard, and vulnerability for stone biodeterioration due to higher plants: the methodological proposal of a multifactorial index (RHV). J. Cult. Herit. 62, 217–229 (2023).

Jiang, X. & Yeo, S. Y. Natural capping enhancing the resilience of earthen heritage under rainfall impacts. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 1, 18 (2024).

Wang, X., Zhang, B., Guo, Q. & Pei, Q. Discussion on the environmental adaptability of weather-resistant measures for earthen sites in China. Built Herit. 6, 19 (2022).

Schlesinger, R. Effectiveness of soft wall capping in conserving ruins[J]. in Proc. of DARCH (DARC, 2021).

Kent, R. Thirlwall Castle: the use of soft capping in conserving ruined ancient monuments. J. Archit. Conserv. 19, 35–48 (2013).

Historic England. Soft capping to protect ruined masonry. 2023. Available from: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/technical - advice/monuments - and - sites/soft - capping/.

Richards, J., Cooke, E. L., Coombes, M., Jones, J. & Viles, H. Are nature—based solutions for built heritage conservation resilient to climate change? The response of grass—based soft caps in Britain and Ireland to future climate scenarios. Stud. Conserv. 70, 1–12 (2024).

Griffin, N. Indictor, R. J. & Koestler, The biodeterioration of stone: a review of deterioration mechanisms, conservation case histories, and treatment. Int. Biodeterior. 28, 187–207 (1991).

Macedo, M. F., Miller, A. Z., Dionísio, A., Saiz-Jimenez, C. Biodiversity of cyanobacteria and green algae on monuments in the Mediterranean Basin: an overview. Microbiology. 155, 3476–3490. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.032508 (2009).

Wang, T. et al. Destruction or protection? Experimental studies on the mechanism of biological soil crusts on the surfaces of earthen sites. Catena 227, 107096 (2023).

Viles, H. A. Durability and conservation of stone: coping with complexity. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 46, 367–375 (2013).

Hanssen, S. V. & Viles, H. A. Can plants keep ruins dry? A quantitative assessment of the effect of soft capping on rainwater flows over ruined walls. Ecol. Eng. 71, 173–179 (2014).

Zhang, B. Research On the Adaptability of Weathering Prevention Technology in Earthen Sites Under Different Climatic Conditions (Lanzhou University 2021).

Yao, X., Zhao, F., Hao, J., Wang, Y. & Hu, R. Plant investigation and the impact on earthen site soil properties in the east city wall of the Sanxingdui site. Herit. Sci 12, 024–01451–7 (2024).

Bu, C., Wu, S., Han, F., Yang, Y. & Meng, J. The combined effects of moss - dominated biocrusts and vegetation on erosion and soil moisture and implications for disturbance on the Loess Plateau, China. PLoS ONE 10, e0127394 (2015).

Xiao, B., Hu, K., Ren, T. & Li, B. Moss - dominated biological soil crusts significantly influence soil moisture and temperature regimes in semiarid ecosystems. Geoderma 263, 35–46 (2016).

Cekstere, G., Karlsons, A. & Grauda, D. Salinity-induced responses and resistance in Trifolium repens L. Urban For. Urban Green. 14, 225–236 (2015).

Richards, J., Cooke, E. L., Coombes, M., Jones, J. & Viles, H. Are nature-based solutions for built heritage conservation resilient to climate change? The response of grass-based soft caps in Britain and Ireland to future climate scenarios. Stud. Conserv. 70, 1–12 (2024).

Ceschin, S., Bartoli, F., Salerno, G., Zuccarello, V. & Caneva, G. Natural habitats of typical plants growing on ruins of Roman archaeological sites (Rome, Italy). Plant Biosyst. 150, 866–875 (2016).

Steinbauer, M. J., Gohlke, A., Mahler, C., Schmiedinger, A. & Beierkuhnlein, C. Quantification of wall surface heterogeneity and its influence on species diversity at medieval castles –implicationsfor the environmentally friendly preservation of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 14, 219–228 (2013).

Zhang, Q. P. et al. Slope aspect effects on plant community characteristics and soil properties of alpine meadows on Eastern Qinghai - Tibetan plateau. Ecol. Indic. 143, 109400 (2022).

Zhang, Q. Y. et al. Effects of slope morphology and position on soil nutrients after deforestation in the hilly loess region of China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 321, 107615 (2021).

Australian Government Office of the Gene Technology Regulator. The Biology of Trifolium repens L. (White Clover) https://www.ogtr.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/2021 the_biology_of_white_clover.pdf.

Prendin, A. L. et al. Influences of summer warming and nutrient availability on Salix glauca L. growth in Greenland along an ice to sea gradient. Sci. Rep. 12, 3077 (2022).

Biggs, D. T. & Gonen, S. Strengthening and conservation of the early Phrygian gate complex at Gordion, Turkey. in Proc. 13th North American Masonry Conference (The Masonry Society, 2019).

Management plan of Liangzhu. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1592/documents/.

China Meteorological Administration. Annual Climate Report 2022. Available from: https://cma.gov.cn/reports.

Pan, C. et al. Research progress on in-situ protection status and technology of earthen sites in moisty environment. Constr. Build Mater. 253, 119219 (2020).

Li, M. & Zhang, H. Hydrophobicity and carbonation treatment of earthen monuments in humid weather condition. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 55, 2313–2320 (2012).

Mordynskiy, A. V. Experimental verification of models for conversion of total solar radiation from a horizontal to inclined plane under climatic conditions of Moscow. Appl. Sol. Energy 57, 430–437 (2021).

Abbas, S. et al. Comparison of seventeen models to estimate diffused solar radiations on a tilted surface. ISES Solar World Congress 2021 Proceedings, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.18086/swc.2021.09.03 (ISES, 2021).

Yang, D. Solar radiation on inclined surfaces: corrections and benchmarks. Sol. Energy 136, 288–302 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Discussion on the environmental adaptability of weather-resistant measures for earthen sites in China. Built Herit. 6, 19 (2022).

Liangzhu Museum. Official website. Hangzhou: Liangzhu Museum. Available from: https://www.lzmuseum.cn/ZhongYaoYiZhi/2019771506777.html.

Hanssen, S. V. & Viles, H. A. Can plants keep ruins dry? Aquantitative assessment of the eff ect of soft capping on rainwater fl ows over ruined walls. Eco. Engin 71,173–179 (2014)..

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Zhejiang Philosophy and Social Science Fund 2024 (Grant Number: 24NDJC262YBM); and Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education (Grant Number: 22YJCZH161). We extend our gratitude to students Zhang Hangnan, Xu Lingyan, Wu Wanyi, Wu Jiaye, and Zheng Yongkang for their diligent efforts in field data acquisition and systematic data curation. We also sincerely appreciate the Management Bureau of Liangzhu Archaeological Site for facilitating data collection and providing interview opportunities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.M. and N.W. wrote the main manuscript text. X.H. and Z.H. prepared figures. Y.L. revised the results and data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, N., Mu, Q., Lu, Y. et al. Topography-driven spatial differentiation in soft capping: vegetation–soil dynamics at Liangzhu earthen sites. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 108 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02364-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02364-3