Abstract

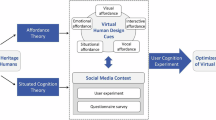

As an important material cultural heritage of China, pottery granary buildings embody the rich social landscape and cultural significance of the Han Dynasty. Due to the current reliance on static displays or fragmented interpretations, it is difficult to intuitively present the relationship between architectural structures and cultural symbols. This study proposes an immersive “miniature experience” framework for digital reconstruction and interactive display. Based on 84 excavated pottery granary samples, the study systematically extracts planar images, chromatic characteristics, and three-dimensional structures to reconstruct three-dimensional virtual models. Using modular modeling techniques, three-dimensional virtual models are constructed, and virtual characters are designed to explore the interior spaces of the buildings. Usability testing (n = 80) revealed that, compared to traditional static display methods, the miniature experience significantly enhanced engagement (mean=3.55 vs. 2.025) and cultural understanding. This study provides innovative strategies for the multidimensional integration of heritage conservation, cultural heritage, and interactive design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

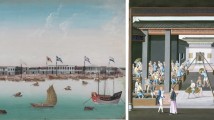

Han Dynasty pottery buildings, as invaluable material cultural heritage, serve as crucial carriers of Han Dynasty culture. Their painted decorations, color combinations, and external forms more intuitively reflect the aesthetic tastes, social hierarchy, regional customs, and economic prosperity of the Han Dynasty1,2,3,4. With the rapid advancement of digital technology, the field of cultural heritage is undergoing a profound digital transformation. Digitalization has not only become an important means of protecting cultural heritage but also a pathway to presenting cultural value5. Through the digital reconstruction of Han Dynasty pottery buildings, static physical artifacts can be integrated with dynamic virtual digital technologies, offering new approaches for their popular science education, dissemination, and academic exchange.

China boasts a long history and rich cultural heritage. Since no intact wooden structures from the Han Dynasty have been discovered to date, the architectural mingqi (pottery buildings) unearthed from tombs serve as invaluable material for exploring Han Dynasty architectural styles. Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings are widely distributed, with their primary concentration in the Central Plains (centered on Henan), as well as in Shanxi and Hebei provinces6. Notably, Jiaozuo in Henan (formerly Shanyang County of Henei Commandery) is part of the core area of Central Plains culture. To date, approximately 110 Han Dynasty pottery buildings have been excavated in Jiaozuo7, mainly concentrated in adjacent tomb clusters such as Baizhuang, Mazuo, and Sulin. Given the concentrated distribution of these artifacts, it is hypothesized that local artisans likely crafted these exquisite pottery buildings8. Therefore, in this study, no strict distinction is made between the specific excavation locations of different tomb clusters within the Shanyang region when discussing typical pottery granary buildings from Jiaozuo.

Early studies on Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings, both domestically and internationally, have primarily focused on image analysis and discussions of stylistic features, as well as scientific analyses of materials, techniques, and pigment compositions6,9. However, systematic three-dimensional virtual reconstruction studies of Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings remain relatively scarce. Therefore, this study starts from the perspective of design and cultural heritage digitization. Moreover, due to the scarcity of painted artifacts available for reference, we had to rely solely on existing image data as a foundation for digital transformation. Given the remote antiquity of the Han Dynasty, most of the painted pottery buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo remained incomplete, posing significant challenges for effective restoration. Due to the scarcity of painted cultural relics available for reference, we could only use existing image data as the basis for digital transformation. The core objective is to extract their typical visual features through digital design, aiming to restore the lost colors and painted patterns of the pottery granary buildings.

Additionally, the internal space of the pottery granary building is presented through interaction with participants via virtual scenes and miniature virtual characters. With the aid of digital technology, participants can gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of the cultural significance inherent in these invaluable cultural heritages.

With the continuous advancement of digital information technology amidst technological development, methodologies for digital research on cultural heritage have progressively matured. Virtual reality (VR) offers an immersive and interactive experience of scenes, exerting a significant influence on the realms of digital cultural heritage and serious games10,11. Early international research primarily focused on digital acquisition and cultural heritage documentation. Harvard University’s Giza Project12 employs panoramic scanning technology; the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has developed virtual experience projects centered on historical narratives13, and numerous other cases and practices utilize VR to showcase cultural heritage14,15,16,17. However, none of the aforementioned foreign studies have addressed the digital transformation of funerary architecture and funerary objects, thereby providing innovative opportunities for this research.

Within China, scholars have extensively explored the digital preservation and restoration of cultural material, such as murals18,19 and costumes20. Digital restoration techniques have been successfully applied to the color and image restoration of Dunhuang murals and computer prototyping21,22,23. Regarding the digital research of cultural heritage from the Han Dynasty in China, the Institute of Han Tombs and Art at Peking University has established the “Chinese Han Dynasty Image Information Database,” utilizing three-dimensional modeling to depict the location of each stone relief in the tombs. However, scholarly research on the digital preservation, restoration, and interactive exhibition of architectural tombs—particularly pottery granary buildings—remains scarce. The development of databases for Han Dynasty unearthed artifacts and tombs still calls for substantial breakthroughs, whereas digital interaction24 and virtual reality technologies have been widely applied in the field of digital cultural heritage, emerging as an inevitable trend for future advancement.

Against this backdrop, the present study focuses on the pottery granary buildings from the Han Dynasty unearthed in Jiaozuo. It reconstructs virtual models through digital approaches and enables viewers to conduct explorations within these virtual environments. In the methodological phase, visual analysis is employed to extract the planar and three-dimensional morphological features of ceramic granary structures, followed by color restoration and modular combination design. In terms of results, a high-precision three-dimensional model of a seven-story painted ceramic granary tower is constructed, and user exploration paths in the virtual environment are planned. Virtual characters are introduced to allow users to explore the internal spaces of ceramic granary towers from a miniature perspective, thereby enhancing immersion and depth of understanding. User experiments are conducted to test the experience effects among different audience groups, evaluate the effectiveness of the design scheme and user experience, and summarize the advantages and development prospects of digital display in presenting traditional cultural relics.

This study fills the gap in the reconstruction of 3D virtual restoration models for architectural funerary pottery granary buildings unearthed in the Jiaozuo region during the Han Dynasty. As a research initiative integrating material cultural heritage with digital technologies (modeling, VR, and interaction design), it provides new research pathways for digital translation, virtual reconstruction, and immersive experience of archaeological materials.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

Visual information processing dominates human sensory perception, and vision enables individuals to extract crucial information from cultural heritage and convert it into digital visual formats. The digitization of cultural heritage involves the use of planar images, three-dimensional structures, colors, interactions, and computer technology to capture multidimensional visual information. This study focuses on the Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings in the Jiaozuo area. By integrating their planar composition elements, color schemes, and three-dimensional structural characteristics, a visualizable 3D model is constructed to provide basic data for virtual restoration.

This study first systematically collected open data on pottery granary buildings unearthed in the Jiaozuo area. Through the compilation of numerous archeological excavation reports, relevant literature, and museum collection catalogs, a total of over 90 images of pottery granary buildings have been collected. To ensure the authenticity and reliability of the image information, the images used in this paper are sourced from four verified databases:

-

(1)

Authoritative published catalogs: Books compiled by the Henan Museum and published by the Jiaozuo Museum7,25,26.

-

(2)

Detailed data comes from archeological excavation reports27,28,29.

-

(3)

Website resources are sourced from the Henan Museum (Seven-story Painted Connected Hall with Pottery Storage building-Henan Museum), China Archeology Network, and the Han Painting Research Institute of Peking University (Han Painting Research Institute of Peking University website).

-

(4)

Images taken on-site at the Jiaozuo City Museum.

The standardized screening of over 90 collected images was conducted to exclude samples with missing critical information caused by incompleteness or shooting angle deviations (with an exclusion rate of 10% of the samples), ensuring the accuracy of the research data. Eventually, 84 pottery granary structures were selected as the core samples for this study, and information such as their types, dimensions, and excavation sites coded and recorded. The Eastern Han Dynasty represented the heyday in the development of pottery granary buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo. Three typical forms—courtyard-style, connected-pavilion-style, and granary-style were selected as key research objects to ensure the representativeness and research significance of the samples.

This paper mainly adheres to the principle of conducting design and restoration based on iconographic evidence. As products of the funerary system, Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings were simulations of the ideal dwellings in the afterlife envisioned by the tomb owners. Their structures (multi-layered design) and painted decorations all carry symbolic meanings. As funerary objects made of pottery, their key differences from actual granaries in the Han Dynasty are as follows: First, earlier scholars believed that pottery buildings were miniature architectural model (Mingqi) from that era30,31, and their various forms reflected different types of above-ground structures in the Han Dynasty, as well as the miniature forms of regional granaries. Second, the internal space of the pottery granary buildings, which could store a limited amount of grain32, was more of a carrier of favorable wishes and spiritual expectations33. Third, the difference lies in the number of layers and the height of the pottery buildings. The high-rise granary buildings (such as the seven-story one) in the Jiaozuo area embody the pursuit and yearning for the concept that “immortals prefer to live in tall buildings” during the Eastern Han Dynasty. Craftsmen realized this symbolic meaning through exaggerated structural features (such as multi-layered pottery buildings). Fourth, the materials used are different: actual granaries were mainly made of wood, earth, bricks, or stones, while pottery granary buildings, as burial objects, took clay as their core material. Craftsmen produced them through processes such as clay body making, shaping, decoration, and firing. Due to the shrinkage property of clay, there are slight deviations in the numerical values of each layer of the existing pottery granary buildings. Fifth, there are differences in structure and technology: actual granaries followed mechanical principles, with their design focusing on load bearing, sealing, moisture-proofing, and earthquake resistance; in contrast, the structural craftsmanship of pottery granary buildings prioritized decoration, with details and structures simplified. For example, the dougong (bracket) components were only used to showcase their frontality and decorativeness, and there were no strictly defined mortise-and-tenon interlocking structures or load-bearing functions in the seven-story painted pottery granary buildings.

Based on the above differences, the restored seven-story pottery building in Jiaozuo does not strictly adhere to architectural accuracy. Unlike the digital restoration of practical buildings (which pursues structural authenticity), this study prioritizes the modular composition and interrelationships of the pottery building, takes into account both its symbolic meaning and form, takes the real pottery building (the pottery granary building in the museum) as the benchmark, and appropriately incorporates design expressions.

This paper divides the design methodology into three parts: planar and 3D feature extraction, color restoration, and module and combination.

Planar and 3D feature extraction

Digital image acquisition enables the preservation of large amounts of image data. Images collected from books, articles, online resources, and museum photographs often suffer from color distortion and low resolution34. This loss of information stems from the poor quality of the original images or the use of inappropriate shooting methods. Image smoothing is key to computer vision and graphics applications35. Therefore, the collected image resources need to be integrated and extracted36.

First, visual elements that can discern the object’s contour are extracted and transformed into graphic symbols. Simultaneously, the shape and decoration of the Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo were retained and artistically refined to form a comprehensive visual design prototype. Second, through the classification and analysis of the forms of pottery granary buildings in the Jiaozuo area, commonalities were identified, and the typical shape outlines of these buildings were extracted. Taking the four-story courtyard-type pottery granary building as an example, the outer contours were extracted sequentially from the images numbered 07, 08, 09, 10, and 26. The contours of each pottery granary building were extracted, and the contours of the overlapping parts were integrated for correction and simplification Fig. 1.

The decorative patterns of the Han Dynasty pottery granary building in the Shanyang region enriched the structure and morphological appearance of the pottery building while also reflecting the esthetic preferences of the Han people. The decorative patterns that frequently appear in the samples are primarily categorized into five types: geometric patterns, figure-and-story motifs, animal motifs, plant motifs, and structural decorations. The typical elements of these patterns have been extracted, summarized, and simplified (Fig. 2). By analyzing the positioning of the patterns, it is observed that the geometric patterns were predominantly used to decorate the front body and corridor sections of the pottery granary building. In contrast, plant, animal, and character patterns are more commonly found on the front and sides of the courtyard and both sides of the main tower. Due to the large surface area of the walls on both sides, intricate storylines can be depicted, enhancing the narrative and entertainment value of the pottery granary’s decorative elements.

Based on the decoration of the four-story painted Han Dynasty pottery granary building unearthed in Jiaozuo, the plane-painted decoration was decomposed. Using geometric forms, the plane image of the pottery granary building was sequentially unfolded from the left, front, right, and back. The front, side, and back decoration drawings of each floor of the pottery granary buildings are then inserted, resulting in a complete, plane-decorated, color drawing building (Fig. 3).

The decoration diagram of the courtyard pottery granary building unearthed in Jiaozuo reveals that the main building’s decoration primarily consisted of geometric and combined patterns. Ancient decorations served not only esthetic purposes but also carried symbolic meanings. Evergreen trees and shield-bearing warriors are commonly seen on the courtyard’s front wall, while Han Dynasty portrait bricks also feature evergreen tree patterns, believed to ward off evil spirits. From the bottom to the top, the back of the main building and the granary body display story-themed paintings such as dragons dancing, dragons distributing rain, and a tiger devouring a female deity. A vermilion evergreen tree is depicted on the granary body with a dragon painted on the right side to invoke rain and resist drought. The fourth floor of the main building features the painting of a tiger consuming a female deity, symbolizing rain prayers and harvest. The decoration on the back of the pottery granary building reflects the abundance of grains. The distribution of decorative patterns correlates with the wall area; window partitions result in smaller wall-painting areas, predominantly featuring simple patterns. In contrast, the walls on both sides of the granary and building bodies are intact, displaying narrative character patterns. The front of the pottery building emphasizes geometric and structural decorative patterns as the primary content, whereas the sides and back feature secondary elements in the form of intricate patterns depicting characters, animals, and plants.

Overall, the patterns in the pottery granary buildings in the Shanyang region exhibited a relatively symmetrical layout, with the wall sections largely painted. The decorative patterns in the colored paintings combine curves and straight lines, and the boundary parts of the building structure are adorned with patterns resembling the dougong (bracket set) style. The pottery granary buildings unearthed in the Jiaozuo area exhibited symmetrical, coordinated, and vivid decorative features.

Color restoration

Color can directly influence visual experiences and is crucial in the practice of digital material heritage. Therefore, extracting color samples from cultural heritage sites is necessary, as it pertains to the accuracy and representativeness of digital color representation. Color configuration holds equal importance in digital design.

The painted pottery granary buildings from the Jiaozuo region, having been buried in a high-humidity environment and subjected to environmental changes after excavation, exhibit such phenomena on their surface paintings as discoloration, peeling, curling, and blistering37. The restoration work was based on the partial painting remains, and the painted results were based on historical materials38. The color restoration data in this study is based on the existing colors of the pottery granary buildings, aiming to restore the original color presentation of the Han Dynasty pottery granary building. This study primarily drew on previous scholars’ colorimetric analysis of the painted pottery buildings from the Han Dynasty Daqu Tomb in Beijing9; the analysis and restoration of painted pottery granary tower fragments unearthed in the Jiaozuo region of Henan Province39; and the analysis of pigment types and colorimetry of the five-story painted pottery granary buildings from Jiaozuo under a polarized light microscope40. Sample analysis was conducted on the seven-story painted pottery granary tower, revealing that its colors include reddish-brown, white, purple, and green. Pigment analysis identified the red and reddish-brown samples as cinnabar41. Building on previous research, the color restoration in this study involves making appropriate adjustments to the lightness and hue of the colors within the environmental context, ensuring the integrity of the restored colors in the virtual environment.

Graphic scientists have developed various color models to quantitatively describe colors. Common color extraction theories include threshold, color model, clustering, and ML-based methods42. Taking the Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo as the research object, researchers extracted reddish-brown, white, and black-and-white colors from the front wall, side walls, and que (watchtower) structure of the fourth floor of the pottery granary building40. This study employed k-means clustering and color mirror clustering techniques. Based on the color analysis of the seven-story painted pottery granary building conducted by previous scholars, it applied k-means analysis to two samples of pottery granary buildings with relatively intact colors (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the color mirror method was used to conduct a more in-depth analysis of color proportions to ensure the accuracy of subsequent design and restoration.

The k-means clustering method is employed to model and analyze the pixel color distribution of an image, extracting dominant colors and their respective proportions in this study. First, the image data is transformed from a three-dimensional RGB matrix (height × width × channels) into a two-dimensional one, where each row represents the RGB values of a single pixel. This preprocessing step simplifies the problem from spatial distribution to color distribution, allowing each pixel to be represented as a point in color space.

In the clustering process, the k-means algorithm is applied to classify all pixels into k-clusters. The algorithm partitions the image matrix \(X=\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\ldots ,{x}_{n}\}\), where \({x}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) represents the RGB values of the i-th pixel into k disjoint clusters\(\{{C}_{1},{C}_{2},\ldots ,{C}_{k}\}\). This is achieved by iteratively minimizing the following objective function:

Where \({\mu }_{j}\) is the centroid (mean RGB value) of cluster \({C}_{j}\), defined as:

At each iteration, the algorithm alternates between two main steps. In the assignment step, each data point xi is assigned to the nearest cluster centroid based on the Euclidean distance, ensuring that:

In the update step, the centroids are recalculated as the mean of the points assigned to each cluster, using:

These steps repeat until convergence, typically defined by minimal changes in the centroids or reaching a maximum number of iterations. After clustering, the number of pixels in each cluster, \(|{C}_{j}|\), is calculated to determine its proportion relative to the total number of pixels n, as given by:

where \({p}_{j}\) represents the percentage of pixels in cluster \({C}_{j}\). These proportions indicate the dominance of each color in the image, and the RGB values of the cluster centers \({\mu }_{j}\) serve as numerical representations of the dominant colors. To enhance interpretability, the clusters are sorted by their proportions \({p}_{j}\) in descending order, prioritizing the most significant colors.

Next, color data from the main areas of the pottery granary buildings was collected using the Image Color Summarizer tool, and the analysis revealed that red accounts for the highest proportion. Six primary colors are identified. Among them, red, brown, and black are the dominant hues, while purple and white serve as auxiliary colors. A total of six primary colors were identified. Among them, the brown areas are mainly where the white background has peeled off; therefore, the dominant colors in the painted pottery granary towers are red, white, and black, with purple and green as auxiliary colors. Inside the pottery granary building, red and white form a strong visual contrast—red outlines the architectural contours and acts as a symbol for floor division, while white serves as the background color of the building9, highlighting the decorative elements. White and red are also colors specifically used in burials: white symbolizes death and yin energy, while red represents life and yang energy43. As a part of the Han Dynasty funeral culture, the pottery granary building reflected the social demands and norms regarding funeral customs and rituals of that time.

Serving as a medium for information transmission, color has symbolic significance. Perceiving and understanding the cultural significance of colors in a virtual cultural heritage experience can significantly improve participants’ learning outcomes44. The diverse colors in the pottery granary building of the Han Dynasty reflect the color system and symbolic meanings of the Han Dynasty. During the Han Dynasty, the theory of divination and the five elements was prevalent, leading to the gradual formation of a five-element color system at the color level. The Jiaozuo pottery granary building’s paintings extensively utilize the colors red, black, and white from the five-element system. The colors of the Han Dynasty carry special symbolic meanings. Each color embodies a specific symbolism. For instance, red symbolizes yang, life, and immortality. Its use in tombs implies the transformation of life and the ultimate destination of the tomb owner. From the Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings, we uncovered a unique color system of material cultural heritage sites.

Modules and combinations

"Module" refers to replaceable components45. A particularly distinctive feature of the design and production of Han Dynasty ceramic architectural models is their modular structure and the capacity for free combination of various components46. The three-dimensional modular structure is a quintessential visual aspect of the Han Dynasty granary buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo. Craftsmen making pottery employ the techniques of mass production and modular construction. For instance, the Lian’ge-style pottery granary building is comprised of 31 modules47, each of which can be disassembled and reassembled.

Taking a five-story courtyard-style pottery granary tower as an example, its modules are divided into the courtyard, which includes double "que", enclosing walls, double-faced main gates, and roofs. The first and second floors of the granary body serve as grain storage areas, with external semi-corridors and staircases acting as dividing markers. The main structure comprises the third to fifth floors, along with partial components such as dougong (brackets) and pottery figurines (Fig. 5).

To validate the feasibility of the previously extracted pottery building elements for digital applications, a seven-story pottery granary building connected to an annex building unearthed in Jiaozuo was chosen as the prototype for digital transformation (The M6 tomb area was excavated in 1993 at the Baizhuang Railway Freight Station in Jiaozuo). The reasons for selecting the seven-story pottery granary building for digital reconstruction are twofold. First, it is uniquely unearthed in the Jiaozuo region and has distinctive regional characteristics. Second, the majority of the existing-colored paintings on the seven-story pottery granary buildings have faded. Restoring the color and texture of cultural objects to their original appearance enhances understanding of their initial state48. Digital reconstruction can provide a crucial reference for restoration.

The four-story, five-story, and seven-story courtyard-style painted pottery granary buildings unearthed in the largest quantities in the Jiaozuo area have their first and second floors as an integral, connected space with no internal partitions. This design symbolizes a granary space filled with grains. For this reason, the number of stories of the pottery granary building is not determined by the roof and the ground, but by the relatively special red borders that mark the structure and number of stories of the building for separation49. In the restoration 3D model, the red border outline lines and structural lines of each floor are visible.

Secondly, each floor of the pottery building is a cube enclosed on all four sides, with an extremely regular shape. Moreover, the archaeological excavation reports in the Jiaozuo area have provided detailed specific information on the size of each floor, which also provides a reliable basis for the accuracy of the restoration work.

In the reconstruction diagram, the red border outlines and structural lines of each floor are clearly visible. Secondly, each floor of the pottery building is a cube enclosed on all four sides, with a highly regular shape. Moreover, the archeological excavation reports for the Jiaozuo area provide detailed parameter information for each floor50,51. To ensure data accuracy, information and data from three seven-story pottery granary buildings were recorded, which also serves as a reliable basis for the accuracy of the restoration work.

-

No. 37 (Seven-story connected-hall pottery granary building unearthed from Tomb M6 in Baizhuang, 1993)

-

No. 38 (Seven-story connected-pavilion-style pottery granary building unearthed from Tomb M1 in the Bo’ai Segment of the Renmin Road Extension Project, Jiaozuo, 2010)

-

No. 41 (Pottery granary building unearthed from Tomb M25 at the Lihe Tomb Construction Site for East Affordable Housing, Jiaozuo, 2008) for comparison

However, some of the data, such as the recorded face width of No. 38 in the archaeological report, is considered incorrect in this study. According to Han Dynasty Tomb No. 1 in Boai County, Henan Province52, the face width of the first floor is 24.5 cm. Nevertheless, judging from the recorded face width of the courtyard, there is a significant discrepancy between the face width of the first floor and that of the courtyard. This study argues that, based on the courtyard’s face width, the face width of the first and second floors should range between 59 and 60 cm. Therefore, a comparison and cross-reference were conducted using the specific parameters and width-to-depth ratios of the three seven-story pottery granary buildings (Table 1).

Based on the above module analysis, the seven-story connected-pavilion-style pottery granary tower can be divided into 12 independent modules (A to L) with a left-center-right symmetrical layout. This structure is further divided into three perspectives: left, center, and right. For instance, Module A includes A1, located on the left side of the courtyard; A2 serving as the courtyard and entrance hall area; and A3 on the right side.

Due to severe color peeling of the seven-story painted pottery granary buildings, the color and pattern decorations on the front part of the courtyard have vanished. The wall decorations of A1 (left) and A3 (right) are symmetrically arranged, and the extracted mural decorative patterns are relatively consistent (e.g. the patterns on A1 and A3 are symmetrical) (Fig. 6).

The two sides of the pavilion corridor, which connect the main hall and auxiliary buildings, are not decorated with colored paintings. Taking A3 as an example for pattern extraction, lines are extracted. In this paper, an edge extraction method with multi-stage preprocessing is applied to the images (Fig. 7and Fig. 8).

First, non-local means (NLM) filtering is applied to denoise the image and mitigate the effects of random noise. NLM filtering computes a weighted average based on the similarity of pixels within a local region, effectively smoothing the noise while preserving edge details. The processed image significantly improves fidelity to weak edges. Subsequently, surface blur is employed to further smooth low-frequency regions while maintaining edge sharpness. Surface blur is implemented using Gaussian blur, with the formula:

where σ controls the degree of blur.

To address potential uneven illumination in the image, a histogram-based brightness balancing technique is applied. By computing the local mean brightness \(\mu (x,y)\) and local standard deviation \({\sigma }_{l}(x,y)\), the intensity of each pixel is standardized using:

where σ is a small positive value to prevent division by zero, this step mitigates inconsistencies in edge gradient magnitudes caused by lighting variations. Following brightness balancing, linear stretching is applied to enhance the global contrast of the image, normalizing the intensity range to [0, 255] and improving the prominence of edge regions.

After preprocessing, Sobel operators are used to compute image gradients. The horizontal and vertical gradient components, \({G}_{x}\) and \({G}_{y}\), are obtained via convolution operations, and the gradient magnitude is computed as:

According to the above steps, edges are extracted using a thresholding operation, where the threshold T is manually determined. Finally, the extracted area, which is of interest, is manually selected and filled with black within certain edge curves.

One of the key principles in creating new combinations lies in the interchangeability of modules. The main building modules of both the courtyard-style and the multi-story connected pottery granary buildings are identical, with the upper floors of the multistory connected-type replicas of the lower modules. The assembly of these modules adheres to Han Dynasty rules, allowing for adjustments in local sizes and details to fit specific locations. For instance, the corridor module can be modified to form a half-space and integrated with stairs to create a cohesive unit. The pottery modules unearthed in Jiaozuo during the Han Dynasty can be disassembled with slight variations in shape and size, yet they follow a consistent pattern of combination. The construction of these pottery granary buildings follows fixed proportions rather than standardized dimensions, making it difficult to find two buildings of the same size. Despite potential deviations in measurement and firing by Han Dynasty craftsmen during production, the proportion between width and depth remains balanced. Taking the seven-story multi-story connected pottery granary buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo as an example, the main body comprises seven floors, divided into three groups of modules: the bottom granary section (first and second floors), the middle section (a combination of the third and fourth floors), and the top pavilion layer (seventh floor). The similarity in module sizes between the third and fourth floors, particularly the close correspondence in form and face width dimensions.

The decorative design of the seven-story Lian’ge-style pottery granary building encompasses line contours, color schemes, and pattern compositions. Through digital restoration techniques, we enhance the color brightness and incorporate geometric patterns. Initially, we integrated the architectural features, simplified the line contours, and redrew the painted murals. Subsequently, based on the six extracted colors, we prepared a reasonable color palette dominated by red, brown, green, and white, with purple, blue, and black as complementary hues. Color matching adheres to the Han Dynasty’s yin-yang and five-element philosophies. Adjustments are made to the color purity and brightness of the pottery granary building, with the saturation of the red framing increased to emphasize its outlines and structures. The front wall of the main building is adorned through the repetition, rotation, and simplification of geometric motifs, while the left and right sides feature symmetrical animal and tree patterns.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been granted an ethical review exemption by Jingdezhen Ceramic University. Prior to the commencement of the study, all participants were informed of the data usage purposes and privacy protection measures, and were explicitly informed that their personal identity information would be strictly kept confidential. The research results will be presented in an anonymized form, and all participants have consented to the use of relevant research data for the academic publication of this paper.

Results

3D model construction

Cultural heritage can be converted into 3D models to facilitate learning and observation by future generations53. The 3D modeling transformation of the pottery granary building unearthed in Jiaozuo during the Han Dynasty was completed based on the design and information derived from its 2D plan. The purpose of constructing the pottery granary building model is to capture its three-dimensional spatial form, and the development of the 3D model is crucial for virtual miniature experience scenarios. The realism represented by 3D graphics enhances the authenticity of the virtual world in terms of sensory and cognitive interaction54. Currently, various modeling techniques are available, such as using cameras or scanners for modeling or image-based modeling. The 3D reconstruction process generated a digital twin of the pottery granary structure, enabling dynamic interaction and analysis of its preservation status.

The visualization of 3D models encompasses three primary stages: 3D modeling, layered texturing, and rendering (Fig. 9). The proportions of the pottery granary buildings are extracted from the image as a reference, from which the dimensions and data for the 3D model are obtained, resulting in the establishment of the 3D model. Subsequently, the details of the 3D granary building model are refined, restoring elements hidden or obscured in the image until its contour and form align with the connected pavilion-style pottery granary building. UV unwrapping is performed on each floor of the pottery granary building to prepare it for color applications. The pottery granary building is then grouped by different areas and colors to facilitate the painting of various floors.

Panel A–C illustrates the 3D modeling workfl ow. Step A involves creating a 3D white model and performing UV unwrapping. Step B includes grouping model components and assigning colors to the main building and annex. Step C covers fi nal adjustments to the overall model, including details and surface texture.

Regarding the coloring treatment of the pottery granary building, each module (including its front and side surfaces) is designed with features corresponding to the painted murals. The restored decorative patterns are then integrated with the 3D modeling (Supplementary Table 1). The design of each floor is integrated with the pottery granary building, followed by adjustments to the color layout details of each floor of the main building and the addition of color to the annex buildings. The next step involves enhancing the material texture effect of the pottery granary building, with aging and wear treatments applied across four aspects: color, metallic finish, roughness, and normals. Lighting plays a crucial role in rendering the pottery granary building. It is primarily adjusted through key light, ambient light, and fill light. Spotlights are utilized to improve the overall lighting effect in the interior and dark corners of the building (Fig. 10).

Virtual scenes

Understanding the three-dimensional spatial characteristics of pottery buildings is crucial for planning two-dimensional routes. During the transition from three-dimensional to two-dimensional space, it is essential to construct the path of the pottery building within the plane. Pottery buildings unearthed in Jiaozuo frequently accentuate frontal chromatic paintings and possess relatively narrow building widths.

The scene design centers on the functional logic of the seven-story connected-pavilion-style pottery granary building, integrating the social characteristics of the Han Dynasty to plan the spatial layout and exploration paths, thereby achieving the dual goals of “structural restoration” and “experience guidance.” The main building area of the seven-story pottery granary building is meticulously planned, with each floor serving a distinct function (Fig. 11).

The first and second floors are granaries. The third floor hosts defensive figurines, while the fourth floor is an entertainment venue showcasing figurines engaged in playing the Liubo Game, reflecting the popularity of Bo games in the Han Dynasty. The fifth floor serves as a rest area, and the sixth floor boasts a lookout figurine to safeguard the security of the pottery granary building.

The original interior of the pottery granary building featured no decorations and no staircases connecting the upper and lower floors; each floor had only two large circular holes. These holes are remnants of Han Dynasty pottery-making techniques, intended to reduce the building’s weight. During the re-optimization process, a navigable structure with rectangular passages and staircases was designed to ensure the smooth movement of virtual characters between different floors.

The ascent route begins at the entrance outside the courtyard, proceeding through the grain intake on the second floor of the pottery granary building. The second floor has stairs for ascending and descending, connecting the third floor, and culminating in access to the highest attic on the sixth floor. Several options are available for descending: first, returning to the third floor from the seventh and exiting via the fourth floor of the annex building; second, jumping from the sixth floor to the corridor outside the fifth floor, navigating along the eaves to the attic, and re-entering the main building via the third-floor corridor; third, exploring alternative routes and discovering new paths independently. These routes are designed to stimulate participants’ curiosity and enhance their understanding of the layout and dimensions of the Han Dynasty pottery granary building.

Virtual character

Virtual characters serve as "avatars" for participants during exploration, and their design must balance historical authenticity with interactive adaptability. In terms of visual design, elements such as hairstyles, makeup, and clothing colors55 of the virtual characters are all derived from Han Dynasty murals and terracotta figurines. Additionally, the characters adopt a cartoon-style design with a 1:3 head-to-body ratio, presenting a compact and miniaturized feature. The height of the characters is set at 8 centimeters, which not only matches the height of the terracotta warehouse building but also ensures compatibility with the dimensions of the stairs and passages in the virtual scene (Fig. 12).

Virtual interactive design

Virtual interactive technology facilitates a closer dialog between cultural heritage and visitors. Virtual technology creates a virtual space for cultural heritage, allowing viewers to explore it. It offers virtual immersion in reconstructed scenes at various levels through projection systems, holographic applications, immersive audiences, and augmented reality (AR)56. Creating a virtual world necessitates multifaceted techniques to capture the real world, model and create scenes, and incorporate narratives and interactive elements. To experience the virtual world, devices such as immersive displays, motion tracking, environmental awareness systems, and command and control technologies are required57.

Through the initial 2D character imagery, a 3D character model is created. Virtual scenes were developed using Unity 3D, with HMDs (Oculus Quest 2) and controllers for navigation. Lighting effects (spotlights for interiors) and texture mapping (surfaces via roughness/normal maps) were optimized for realism. The virtual environment was developed using the Unity 3D engine and is compatible with the Oculus Quest 2 headset and its accompanying controllers. Character movement is controlled via the WASD keys, with the spacebar regulating jumping actions to simulate a real-time exploration experience. Lighting effects (including indoor spotlights) and texture mapping, where surface effects are achieved through roughness and normal maps, have been optimized to enhance realism (Fig. 13).

Usability test design

The test was conducted using a comparative experimental design58, divided into two modes: “virtual miniature experience” and “traditional static viewing.” Participants were split into two groups: one engaged with a virtual 3D model through the miniature experience mode, while the other adopted the traditional viewing mode. By randomly assigning participants to each group, baseline characteristics were balanced to minimize bias. This design facilitated the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data, thereby providing a comprehensive view of the differences in experience between the two groups.

Game-based learning is increasingly being utilized in virtual museums to enhance cultural awareness and motivate public engagement with cultural institutions59. Studies have shown that immersive virtual environments enhance participants’ comprehension of complex information, as multisensory interactive feedback significantly facilitates knowledge absorption60. On the other hand, miniature interactions can swiftly capture participants’ attention, enabling them to establish an interactive connection with the pottery granary scene. Virtual heritage is a learning medium, but it focuses on the audience learning for themselves the significance and value of the heritage content that is digitally simulated61. By manipulating virtual characters to enter the pottery building space, it emphasizes “human-computer collaboration.” Therefore, it is imperative to conduct user experience testing on the newly constructed virtual pottery granary scene, allowing users to provide positive feedback and suggestions for further enhancement.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the miniaturized experience, 80 participants were divided into two groups: the experimental group engaged with the miniaturized interactive device, while the control group viewed static 3D models.

The participants consisted of 80 volunteers (aged 24-45, standard deviation = 8.5 years) recruited via email, online platforms, and cultural heritage forums. To ensure sample diversity, the cohort included 33 undergraduates, 18 graduate students, 15 cultural heritage enthusiasts, 8 doctoral students, 5 majors in archeology and museology, and 1 computer science major. Among them, there were 38 males and 42 females. Participants were randomly assigned to the two groups:

-

Experimental group (n = 40): Participants engaged in a “miniature experience” of the seven-story pottery building. Using miniature virtual avatars, they entered a 3D virtual reconstruction of the scaled-down seven-story pottery building, where they accessed interactive information and dimensional details of the structure. This experience was facilitated via VR headsets and interactive controllers.

-

Traditional group (n = 40): Participants in this group viewed the seven-story pottery building independently via a desktop interface, with interactions limited to traditional visual browsing and textual descriptions of the exhibit. They were unable to access the interior of the seven-story painted pottery building and had no virtual character experience.

The participants’ experience phase is as follows. First, both groups received 5 minutes of basic instruction and 5 minutes of free exploration time. Next, the experimental group operated the joystick and explored the virtual building for 20 minutes, while the traditional group browsed static models and related text information for the same amount of time. Finally, after the experience, the participants immediately completed the user experience questionnaire. The User Experience Scale (UES) was adopted, with details presented in Table 2. A 5-point Likert scale62 was utilized for data collection through questionnaires, where responses were scored as follows: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. This scale assessed five dimensions to evaluate Engagement, Cultural Understanding, Interaction Satisfaction, Digital Form Perception, and Cultural Heritage Promotion Effectiveness. Data analysis, including t-tests and regression analysis, was performed using SPSS 26 software. The validity of the questionnaire was verified through a pre-experiment, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.87. Since this value is greater than 0.7, it indicates that the questionnaire has good reliability. Independent samples t-tests compared group differences (α = 0.05). Regression analysis examined the relationship between engagement and cultural understanding. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to quantify practical significance.

In terms of the degree of participation, the miniature experience group scored an average of 3.55, while the traditional group scored an average of 2.025, as shown in Table 3. The difference between the two groups was 1.525, indicating that the average participation level of the miniature experience group was significantly higher than that of the traditional group. According to the results of the independent sample test regarding participation variables, the F value of Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance was 1.557, with a p-value of 0.216, suggesting that the variances of the two groups were equal. The t-value of the independent sample test was 6.616 (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 4. Overall, the miniature experience group significantly outperformed the traditional group regarding participation, demonstrating the positive role of miniature experiences in enhancing engagement.

Participants’ understanding of the Han Dynasty pottery granary Building was measured through their experiences. The miniature experience group scored an average of 3.45, while the conventional experience group scored an average of 2.4(t78 = 4.12, p < 0.001, d = 0.93).

Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances yielded a result of p > 0.05, indicating that the data satisfied the homogeneity of variances assumption. Further analysis using an independent samples t-test confirmed that the experiential perceptions between the two groups were statistically significant and practically meaningful: the miniaturized experience group outperformed the traditional group in terms of immersion, scene immersion, and information acquisition efficiency. This discrepancy can be attributed to the active interaction model of “virtual character control + spatial exploration” in the miniaturized experience. In contrast to the traditional group, which passively observed static models, the experimental group established an “operation - feedback - cognition” closed-loop through actions such as character movement and perspective switching.

Engagement: The experimental group exhibited significantly higher engagement (Mean=3.55, SD = 1.01) compared to the control group (Mean=2.03, SD = 1.05; t78 = 6.62, p <.001, d = 1.51). This notable difference can be attributed to the “Miniature experience” featuring interactive elements such as character navigation and jump mechanics. Unlike some prior studies where passive viewing was the norm, these interactive features actively invited participants to engage, fostering a more immersive experience. The large effect size(d = 1.51) indicates that these design elements were highly effective in promoting active participation, aligning with and extending the findings of a previous study on cultural heritage experience design.

Culture Understanding: A positive correlation was found between engagement and culture understanding (r = 0.80, p <.001). During the experiment, participants who actively explored the virtual building spent more time observing details. For instance, they manipulated virtual models to examine multi-story modules from different angles. Such embodied interactions led to a deeper comprehension of architectural features, suggesting that hands-on engagement significantly enhances knowledge retention.

Interaction: The interaction score of the miniaturized experience group (M = 3.53, SD = 1.09) was significantly higher than that of the traditional group (M = 2.08, SD = 1.05; t78 = 6.08, p < 0.001, d = 1.36). This result confirms the effectiveness of the “human machine collaboration” design: the size of the virtual characters (8 cm in height) is appropriately scaled to the proportions of the pottery granary building space, enabling participants to naturally perform coherent actions such as ascending and descending stairs through interactive controls (e.g., VR controllers).

Digital Form Perception: The micro-experience group achieved a significantly higher score (M = 3.50, SD = 1.20) than the traditional group (M = 2.15, SD = 1.05; t78 = 5.36, p < 0.001, d = 1.21). This superiority can be attributed to multi-dimensional visual presentation, such as layered deconstructed 3D models and dynamic color reproduction. Participants were able to “enter” the interior of the granary pottery building via virtual characters, thereby intuitively perceiving the spatial relationships among “outer contours, internal structure, and decorative details,” whereas the traditional group only had access to static external renderings.

The regression model, as shown in Table 5, indicates that participation has a significant predictive power for the level of understanding of Han Dynasty pottery granary building knowledge (β = 0.8, p < 0.001), accounting for 64% of the variance (R² = 0.64). Specifically, for every 1-unit increase in participation, the cultural understanding score increases by an average of 0.78 units. This result empirically supports the theory that “active participation promotes knowledge internalization”. By independently exploring details such as the “storage functional zones” and “defensive structural design” of the pottery warehouse, participants construct a more comprehensive knowledge framework. For example, 33 out of 40 participants in the experimental group (82.5%) could correctly describe the functional layering of the pottery warehouse as “lower level for grain storage - upper level for defensive observation,” while only 18 out of 40 participants in the traditional group (45%) were able to do so.

This study, through data analysis, reveals that the digital dissemination of cultural heritage must extend beyond the single dimension of “visual reproduction” and shift toward a multimodal integration of "interaction-perception-cognition." The advantage of miniature experiences lies in transforming abstract architectural knowledge into operable spatial exploration, enabling the cultural connotations of "earthenware warehouses as funeral symbols" (such as decorative patterns, colors, and morphological characteristics) to be naturally perceived through interactive behaviors, rather than being passively received or explained through text. This provides a replicable design paradigm for future cultural heritage digitization projects. It is recommended to prioritize the integration of “role-based exploration” and “scenario-based interaction” elements to balance academic rigor with public accessibility.

Discussion

This paper employs methods such as three-dimensional modeling, virtual scene construction, interactive design optimization, and user experience testing to establish a virtual miniature experience system for the Han Dynasty Jiaozuo pottery granary buildings, with a typical seven-story connected pavilion-style pottery granary building in the Jiaozuo region used as a case study for system validation. Characterized by architectural form restoration, colored decoration reproduction, modular interactive design, and user cognitive load optimization, this experience system can effectively achieve immersive display and in-depth interpretation of cultural heritage architecture. Furthermore, the effectiveness and application value of the system have been verified through objective data from between-group comparison experiments (t-tests), quantitative feedback from user experience scales, and behavioral analysis of scenario-based exploration. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

(1)

The virtual miniature experience system constructed in this study breaks through the limitations of traditional static displays. Through a three-tiered design consisting of “architectural restoration, scene narration, and interactive exploration,” it provides a new approach for the digital interpretation of cultural heritage buildings, enriching theoretical research on the integration of cultural heritage and digital technologies.

-

(2)

The system offers practical tools for the digital preservation of architectural artifacts such as Han Dynasty pottery buildings, the supplementation of archeological information, and public education, thereby facilitating innovation in museum exhibitions and the living transmission of cultural heritage.

However, this study also has certain limitations that merit further discussion. First, the virtual reconstruction was limited to a single model object, which may have led to inflated engagement scores in the experimental testing. While this object’s design and evaluation process are detailed, other cultural heritage items may utilize different digital mechanisms and cater to various audiences. Future research should strive to recruit more diverse and representative samples. For instance, stratified sampling techniques could be adopted to include individuals with varying levels of interest in cultural heritage and technical proficiency. This would help ensure that the research conclusions can be more accurately generalized to different demographic groups. Future research can further assess its effectiveness based on the usability evaluation conducted in this study. Second, the system was created by using and redesigning available open data, instead of including every detail about the Jiaozuo Pottery granary buildings. The actual height of the Jiaozuo seven-story pottery granary buildings ranges from 185 to 199 centimeters63, and a full-scale scanning analysis is currently not feasible. Moving forward, more detailed virtual 3D models (such as those of Han Dynasty cluster-style pottery building complexes) could be constructed via design modeling to further explore the architectural combination patterns embodied in Han Dynasty architectural artifacts. Third, this study aims to propose a design strategy, it has yet to be systematically evaluated and verified. Future research can further assess its effectiveness based on the usability evaluation conducted in this study.

In summary, this study extends the concept of digitization to the field of cultural heritage preservation. Constructing a virtual model of Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings, it fills a gap in the virtual reconstruction and interactive testing of Han Dynasty pottery granary buildings. The research aims to realize the comprehensive protection and widespread dissemination of this precious Han Dynasty cultural heritage, with the expectation that it will find broader applications in archeological research and serious games in the future.

Data availability

Due to the ongoing nature of the research and concerns regarding participants’ privacy, only the data presented in this article are publicly available. However, upon reasonable request and with appropriate ethical approval, the corresponding author can provide representative processed data.

References

Chen, Z. On the Economic Historical Materials of Han Dynasty (In Chinese) 171-172 (People’s Publishing House of Shanxi, Xi’an, China, 1980).

Cheng, W. The art of decoration of the Taocang building in Han Dynasty. Decoration 1, 118–119 (2010).

Li, S. S. Han dynasty architectural burial Objects. J. Natl. Mus. China 9, 101–121 (2012). CNKI:SUN:ZLBK.0.2012-09-008.

Wu, W. Funeral concepts reflected in Han Dynasty Model Mingqi. Cult. Relics Cent. China 4, 75–81 (2014).

Marcum, D. B. Digitizing for access and preservation: strategies of the Library of Congress. First Monday Urbana-Champaign, USA 12, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v12i7.1924 (2007).

He, X. et al. Exploring pottery origin by composition and technique comparison: a case study at the Daqu burial site, Beijing, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 126 (2024).

Han, C. S. Jiaozuo pottery granary buildings (in Chinese) (Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House of Henan, Zhengzhou, China, 2015).

Tite, M. S. Pottery production, distribution, and consumption: the contribution of the physical sciences. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 6, 181–233 (1999).

Go, I. et al. A multi-analytical approach to identify ancient pigments used in pottery towers excavated from the Han dynasty tombs. Herit. Sci. 11, 227 (2023).

De Paolis, L. T., Aloisio, G., Celentano, M. G., Oliva, L. & Vecchio, P. Experiencing a town of the Middle Ages: An application for the edutainment in cultural heritage. 2011 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Communication Software and Networks, Xi'an, China, 169-174 (2011).

Zilio, D., Orio, N. & Zamparo, L. FakeMuse: A serious game on authentication for cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 14, 1–22 (2021).

Manuelian, P. D. Giza 3d: Digital archaeology and scholarly access to the giza pyramids: the Giza project at Harvard University. Digit. Herit. Int. Congr. (Digit. Herit.) 2, 727–734 (2013).

Jarzombek, M., Keller, E. & Mann, E. Site, archive, medium and the case of Lifta. Tradit. Dwell. Settlem. Rev. 33, 21–34 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27190878 (2022).

Loizides, F., El Kater, A., Terlikas, C., Lanitis, A. & Michael, D. Presenting Cypriot cultural heritage in virtual reality: A user evaluation. In: Digital Heritage. Progress in cultural heritage: documentation, preservation, and Protection: 5th International Conference, EuroMed 2014, Limassol, Cyprus, November 3-8, 2014. Proceedings 5. Springer, 572-579 (2014).

See, Z. S., Santano, D., Sansom, M., Fong, C. H. & Thwaites, H. Tomb of a Sultan: a VR digital heritage approach. In: 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018). IEEE. 1-4 (2018).

De Paolis, L. T., Chiarello, S., Gatto, C., Liaci, S. & De Luca, V. Virtual reality for the enhancement of cultural tangible and intangible heritage: The case study of the Castle of Corsano. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 27, e00238 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Gamification of virtual museum curation: a case study of Chinese bronze wares. Herit. Sci. 12, 348 (2024).

Zheng, S. Intangible heritage restoration of damaged tomb murals through augmented reality technology: A case study of Zhao Yigong Tomb murals in Tang Dynasty of china. J. Cult. Herit. 69, 135–147 (2024).

Liu, Z., Chen, D., Zhang, C. & Yao, J. Design of a virtual reality serious game for experiencing the colors of Dunhuang frescoes. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–31 (2024).

Loke, G. et al. Digital electronics in fibres enable fabric-based machine-learning inference. Nat. Commun. 12, 3317 (2021).

Li, X., Lu, D. & Pan, Y. Color restoration and image retrieval for Dunhuang fresco preservation. IEEE Multimed. 7, 38–42 (2000).

Liu, Z., Liu, S. & Fan, S. Research on the virtual restoration of faded Dunhuang murals with a global attention mechanism. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 35 (2025).

Ren, H. et al. Dunhuang murals image restoration method based on generative adversarial network. Herit. Sci. 12, 39 (2024).

Dragoni, M., Tonelli, S. & Moretti, G. A knowledge management architecture for digital cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 10, 1–18 (2017).

Henan Museum. Han Dynasty Architectural Mingqi Unearthed in Henan (in Chinese) (Elephant Press, Zhengzhou, China, 2002).

Han, J. & Liu, X. The Trace of Shanyang: Comprehensive Research on Han Dynasty Pottery Granary Buildings (in Chinese) (Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House, Zhengzhou, China, 2018).

Han, C. S. et al. Excavation brief of Tombs M121 and M122 at Baizhuang, Jiaozuo, Henan. Cult. Relics Cent. China 6, 10–27 (2010).

Jiaozuo Municipal Cultural Relics Work Team, School of Fine Arts, Jiaozuo Teachers College Excavation brief of Han tomb M51 at Baizhuang, Jiaozuo, Henan. J. Natl. Mus. China 7, 6–21 (2012).

Suo, Q. X. The Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb No.6 at Baizhuang in Jiaozuo, Henan. Archaeology 5, 396–402 (1995).

Han, D. J. An essay on the causes of the decline of Nubang architecture in the Han Dynasty: earthquake impact theory. J. Arch. Hist. 11, 146–149 (2002).

Li, R. S. Funeral customs of the Han Dynasty (in Chinese) 130–156 (Shenyang Publishing House, Changchun, 2003).

Wei, W. On the Periods and characteristic of pottery storage buildings unearthed from Han tombs in Henan. Cult. Relics Cent. China 2, 62–66, 72, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-1731.2011.02.007 (2011).

Sun, Z. X. et al. Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art by Yale University Press, New York, New Haven, Conn, USA, 2017).

Xia, D. H. et al. Material degradation assessed by digital image processing: Fundamentals, progresses, and challenges. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 53, 146–162 (2020).

Feng, Y. et al. Easy2hard: Learning to solve the intractables from a synthetic dataset for structure-preserving image smoothing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 7223–7236 (2021).

Enninful, E. K., Boakye-Amponsah, A. & Vanderpuye, P. An empirical analysis of technology-induced image fading in digital prints among photography students. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 17, 53–81 (2023).

Liu, X. & Zhou, R. H. Taking cultural relics protection and restoration as a lifelong career: a record of the protection and restoration work of pottery granary towers in Jiaozuo Museum. Cult. Relics Restor. Res. 0, 304–310 (2018).

Fieberg, J. E., Knutås, P., Hostettler, K. & Smith, G. D. “Paintings fade like flowers”: pigment analysis and digital reconstruction of a faded pink lake pigment in Vincent van Gogh’s undergrowth with two figures. Appl Spectrosc. 71, 794–808 (2017).

Liu, X. Study of polychrome potteries excavated from Han Dynasty tombs at Macun and Baizhuang in Jiaozu. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 33, 97–102 (2021).

Liu, X., Pan, C. M. & Zhao, H. J. Scientific and technological protection of the Han Dynasty five-storey painted pottery granary building in the collection of Jiaozuo Museum, Henan Province. Yellow River, Loess, Yellow Race 2, 47–49 (2022).

Ji, B. G. & Li, J. W. Analysis on the Colored Pottery Buildings. Cult. Relics Cent. China 5, 110–115 (2015).

Ni, M., Huang, Q., Ni, N., Zhao, H. & Sun, B. Research on the design of Zhuang brocade patterns based on automatic pattern generation. Appl. Sci. 14, 5375 (2024).

Chen, S. L. Architectural features and cultural research reflected by Mingqi artifacts in the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties (in Chinese). Dissertation. (Xian University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2014).

Hou, Y., Kenderdine, S., Picca, D., Egloff, M. & Adamou, A. Digitizing intangible cultural heritage embodied. State of the art. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 15, 1–20 (2022).

Ledderose, L. Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, USA, (2000).

Wen, J. Q. et al. Analysis of the firing and molding techniques of painted pottery towers excavated from the Daqu Tombs in Beijing. Res. Conserv. Cave Temples Earth. Sites 2, 50 (2023).

Suo, Q. Eastern Han tomb No. 6 at Baizhuang, Jiaozuo, Henan. Archaeology 5, 396–402 (1995).

Tong, Y., Cai, Y., Nevin, A. & Ma, Q. Digital technology virtual restoration of the colours and textures of polychrome bodhidharma statue from the Lingyan Temple, Shandong, China. Herit. Sci. 11, 12 (2023).

Liu, G. A Study on Architectural Images of the Han Dynasty: Centered on the Regions of Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan and Anhui. (in Chinese), Guangxi Normal University Press, Guilin, China (2020).

Han, C. S. et al. A tentative analysis of the seven-story connected-pavilion painted pottery granary tower unearthed from the Han tomb in Lihe, Jiaozuo. J. Natl. Mus. China 1, 54–60 (2010).

Han, C. S. & Cheng, W. G. On the Pottery Models of Storage Building Connected by Passageway Unearthed from Jiaozuo Area Henan Province. Cult. Relics Cent. China 4, 70–74 (2014).

Jiaozuo Municipal Archaeological Team Han Dynasty Tomb Ml Discovered at Boai, Henan Province. J. Natl. Mus. China 11, 6–18 (2012).

Fusco Girard, L. & Vecco, M. The “intrinsic value” of cultural heritage as driver for circular human-centered adaptive reuse. Sustainability 13, 3231 (2021).

Pagano, A., Pietroni, E., & Poli, C. An integrated methodological approach to evaluate virtual museums in real museum contexts. In: ICERI2016 Proceedings, pp. 310–321 IATED (2016).

Liu, K., Zhou, S. & Zhu, C. Historical changes of Chinese costumes from the 30 perspective of archaeology. Herit. Sci. 10, 205 (2022).

Bergamasco, M., Falvo, P. G. & Manera, G. V. Perceiving cultural heritage. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2, 2–5 (2018).

Siddiqui, M. S., Syed, T. A., Nadeem, A., Nawaz, W. & Alkhodre, A. Virtual tourism and digital heritage: an analysis of VR/AR technologies and applications. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 13, 303–315 (2022).

Collier, D. The comparative method. In: Finifter, A. W. (ed.) Political Science: The State of the Discipline II, pp. 105-119, American Political Science Association, Washington, DC, (1993).

C´osovi´c, M. & Brki´c, B. R. Game-based learning in museums—cultural heritage applications. Information 11, 22 (2019).

Santamar´ıa-Bonfil, G., Ib´an˜ez, M. B., P´erez-Ram´ırez, M., Arroyo-Figueroa, G. & Mart´ınez-A´lvarez, F. Learning analytics for student modeling in virtual reality training systems: Lineworkers case. Comput, Educ. 151, 103871 (2020).

Champion, E. Entertaining the similarities and distinctions between serious games and virtual heritage projects. Entertain. Comput. 14, 67–74 (2016).

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S. & Pal, D. K. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl Sci. Technol. 7, 396–403 (2015).

Cheng, Z., Cheng, W. G. & Han, C. S. Artistic Miniature of Real House: Pottery Barn Building of Han Dynasty Unearthed from Jiaozuo. Decoration 7, 75–77 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the major art project of the National Social Science. Foundation in 2024 (24ZD15). The research topic is “International Strategy for Chinese Ceramic Art.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Scheme design: Liu, Y.S., Lyu, X.B.; Pottery granary building data collection and manuscript writing: Liu, Y.S., Lyu, X.B.; Data analysis and user testing: Zhang, X.W.; Modeling and software implementation: Li, W.H.; Figures and charts presentation: Liu, Y.S.; Supervision: Lyu, X.B. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Lyu, X., Zhang, X. et al. Research on the digital design of Han Dynasty pottery granary building based on miniature experience. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 104 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02367-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02367-0