Abstract

Background

Obesity is a modifiable risk factor associated with hospital-associated complications. Recent studies show there is a high prevalence of patients with obesity presenting to hospital and evidence indicates that people living with obesity should receive diet advice from a dietitian; however, patients often do not receive this care in acute settings.

Aim

The primary aim of this study was to explore the experiences of dietitians caring for patients living with obesity in acute hospital settings.

Methods

A multi-site qualitative study was conducted from October 2021 to November 2023 in Melbourne, Australia. Constructivist grounded theory methodology informed sampling and data collection. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with dietitians working in acute care. Data were analysed using open coding and constant comparison underpinned by Charmaz’s framework.

Results

Interviews were conducted with 25 dietitians working across four hospitals. The theory developed from the data describes an enculturated decision-making process whereby acute clinical dietitians are limiting acute nutrition care for people living with obesity in hospital. The theory includes five interdependent categories that influence clinical decision-making and practice: (1) culture of professional practice, (2) science and evidence, (3) acknowledgement of weight bias and stigma, (4) dietitian-led care and (5) hospital systems and environment.

Conclusion

The findings from this study provide new insights as to why dietitians may not be providing acute nutrition care for people living with obesity. Strategic leadership from clinical leaders and education providers together with the lived experience perspectives of people with obesity is needed to shift the culture of dietetic professional practice to consider all nutrition care needs of patients living with obesity who are accessing acute hospitals for health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overweight and obesity are considered ‘wicked problems’ [1] in healthcare as they are shaped by a complex interplay of individual, behavioural, social and environmental factors [2]. The prevalence of obesity is growing globally [3], as is the prevalence of obesity seen in acute hospitalised patients [4,5,6]. Obesity impacts healthcare practice, costs and service delivery in primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare settings and contributes to a significant proportion of hospital admissions [7,8,9,10]. It is a modifiable risk factor associated with hospital-associated complications such as post-operative infection, sepsis, pressure injuries and intensive care unit admissions [8, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Dietitians are ideally placed with the training and expertise to manage obesity. People living with obesity are often referred to [18] and regularly managed by dietitians [19]. Dietitians are considered by health professionals to be the most effective providers of weight management advice [20,21,22], with their integration into the health care team perceived to be both valuable and beneficial for obesity management [23]. For adults living with obesity, weight management interventions led by a dietitian, or a multidisciplinary team that includes a dietitian, have achieved greater weight loss and been effective for improving cardiometabolic outcomes and quality of life [24,25,26]. Patients value dietitians in this area, believing that specialised clinical bariatric dietitians are vital to improving their health due to their clinical expertise [27]. The public rank dietitians as one of the most popular sources of professional advice regarding obesity [18].

Despite dietary intervention being a key component to weight management, and the positive perception of dietitians in managing obesity, people living with obesity often do not receive dietetic care during an acute hospital admission [4]. This is problematic as people with obesity may lack essential nutrients required for recovery due to increased metabolic rate and protein catabolism during critical illness, are at risk of muscle mass loss and may have underlying malnutrition, sarcopenia, or micronutrient deficiencies [28]. People with obesity also have a higher burden of chronic disease, with comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease [12]. Without suitable acute nutrition care in the acute setting for people with obesity, their recovery from illness may be impeded, resulting in increased length of hospital stay and poorer health outcomes [17]. The factors that influence decision-making for nutrition care by dietitians for people living with obesity in acute hospital settings are currently unknown. The primary aim of this study was to explore the experiences of dietitians caring for patients who co-present with obesity in the acute care setting.

Methods

A multi-site, qualitative study was conducted from October 2021 to November 2023 in Melbourne, Australia. Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory methodology was used [29, 30] due to the lack of empirical evidence or theory explicating the gap in acute nutrition care for people with obesity from the perspective of dietitians. Among various qualitative approaches, grounded theory has been used to explore other ‘wicked problems’ including climate change [31, 32] and food insecurity [33]. Grounded theory studies are iterative and entail cycles of concurrent data collection and analysis [30, 34]. Constructivist grounded theory is underpinned by a paradigm of constructivism where the researcher co-constructs theory through their interactions with participants and data [29, 30, 34].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 26547). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all dietitian participants.

Research team positionality and reflexivity

The research team consisted of four female clinician-researchers: dietitians with acute clinical experience (AE, SG, JB), academics involved in post graduate dietetic programs and experienced in qualitative research methodology (SG, JB) and a physiotherapist with acute clinical experience and research experience with constructivist grounded theory (CM). Charmaz’s grounded theory methodology recognises the researcher as being actively involved in the research process [35, 36]. Reflexivity was practiced by the research team as recommended in constructivist grounded theory. Reflections were documented within written memos. As data analysis progressed, developing codes and categories were reflexively critiqued in research team meetings [37].

Participants/sampling

Participants were dietitians practising in acute care who had experience of caring for patients with obesity in acute hospitals, recruited through purposive sampling via emails to the authors’ professional networks. Additional participants were recruited via snowball sampling where initial participants identified colleagues who met the study eligibility criteria. Theoretical sampling was used to recruit participants for their ability to confirm or challenge the developing concepts, and to understand the evolving theory [35, 38,39,40]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

The initial interview guide was developed based on the thematic findings of a qualitative systematic review exploring dietetic service and care delivery, including themes specific to patients: desire for individualized care and impacts of nutrition care; and theme of accessing dietetic service [41]. Aligning with grounded theory methods and theoretical sampling [38], interview questions were iteratively adapted as the study progressed [35, 39]. The interview guide was piloted with one test participant to ensure coherence, flow and that questions elicited rich data as per qualitative interview guidelines [42].

Demographic data was collected from participants prior to their interview. Field notes capturing researcher observations and reflections were written during and after interviews. Interviews were conducted via web-based video conferencing platforms. Median interview duration was 39 min (range: 27–52). Interviews were conducted by AE and SG; all interviews were transcribed verbatim by AE.

Data analysis

Demographic data was analysed descriptively. Interview data analysis was conducted according to the steps described by Charmaz, with five steps completed [29, 34]. First, for each interview transcript, data were examined line-by-line, and codes were attributed to words or sentences to categorise the data. Second, open coding commenced after the second interview, creating tentative labels for data to summarize meaning. Constant comparison technique was applied to the whole interviews to distinguish similarities and differences between codes. Third, focused coding led to the development of theoretical categories. To explore the tentative categories and confirm or challenge the developing theory, theoretical sampling was used in both interview questions and participant recruitment. The final stage was writing theory and theoretical categories. Findings were presented during regular meetings where raw data were discussed, analysis critiqued, gaps in categories identified and potential analytical avenues raised. Data collection and analysis ceased when theoretical saturation was reached, this was when no new properties of categories were garnered when new data was added, and categories were robust enough to encompass variations as per grounded theory methods [35]. Verbatim participant quotes were extracted to illustrate themes. Input into steps three and four was provided by CM through face-to-face meetings and written review of theoretical categories.

Results

Twenty-five dietitians participated in individual interviews. Most participants identified as female (n = 24), with 11 participants having practised as a dietitian for <10 years. Participants worked across diverse areas of the acute care setting including cardiology, critical care, diabetes, gastrointestinal surgery, gastroenterology, general medicine, leadership/ management, mental health (including eating disorders), nephrology and surgery, with three working specifically in bariatric surgery services (refer to Table 1 for patient demographics).

Theory overview: “limiting acute nutrition care”

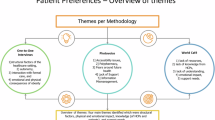

The theory developed in this study was limiting obesity-related acute nutrition care. The theory describes: an enculturated decision-making process whereby acute clinical dietitians are limiting acute nutrition care for people living with obesity in hospital. The theory includes five interdependent categories that influence clinical decision making and practice: (1) culture of professional practice, (2) science and evidence, (3) acknowledgement of weight bias and stigma, (4) dietitian-led care and (5) hospital systems and environment (Table 2). Within each category there was a common concern about implementing non-surgical weight loss interventions in the acute care environment that underpinned current decision making to avoid or limit obesity-related care in acute settings. Figure 1 is a conceptual model of the categories and relationship.

Note. The circles represent the categories that influence dietetic clinical practice. The arrows symbolise a shared concern about implementing non-surgical weight loss interventions and highlights the complex interplay between factors that result in dietitians limiting acute nutrition care for people living with obesity in hospital settings.

Theory categories

Culture of professional practice

The core category of culture of professional practice reflected a collective experience of avoiding weight management care for people living with obesity in the acute hospital setting. This prevailing culture, in part, appeared to be supported and justified by the use of clinical triage tools: clinical triage tools (developed to manage clinician workloads and rationalise dietetic resources) focused on patient safety and risk, deprioritised weight management and strongly emphasized prevention of hospital-acquired malnutrition. High-risk acute nutrition issues prioritised for clinical care included malnutrition, nutrition support, post-surgical nutrition care and management of nutrition impact symptoms including loss of appetite. Participants shared that part of their professional practice identity was to manage and resolve high-risk nutrition issues, demonstrating their value to patient care. Several participants identified that the emphasis on prevention of hospital acquired malnutrition and unintentional weight loss resulted in the perception that any weight loss of a patient under their care would be seen as negative, creating an environment of fear. There was some curiosity as to whether this practice was evidence-informed, however, this was insufficient to trigger change in practice. Some participants acknowledged that they were likely perpetuating this culture of avoiding weight management in acute care by not educating patients regarding the potential benefits of weight loss.

Participants described a historical culture of declining referrals for weight management as this was viewed as a long-term or chronic health issue. Participants identified that chronic diseases such as obesity should be managed in the primary care setting, even if weight status impacted the person’s current health condition. Counselling for weight management was perceived as time consuming and longer term than the acute setting allowed. Some participants viewed weight management external to their professional role in an acute hospital. They described there was little professional benefit to providing nutrition intervention for weight management in acute settings, reporting this may decrease job satisfaction, negatively impact therapeutic alliance, and that weight loss should not be a priority for patients with an acute health issue. Some participants disagreed with this prevailing view and advocated for obesity related care by dietitians in acute settings however, understood the evolution of limitations imposed on care delivery.

Participants posited that university dietetic curricula likely contributes to the current professional practice culture. They purported that dietetics students are taught to compartmentalise nutrition care within settings. For example, weight management is promoted as an intervention reserved for primary care settings. Participants observed that dietetic students came to the practicum placement without required knowledge of obesity as a disease and lacked the knowledge and skills required to offer interventions and education for patients related to obesity, perpetuating the culture of limiting obesity-related nutrition care.

Science and evidence-based practice

Participants self-described that their professional identity was both ‘dietitian’ and ‘scientist’. They identified a desire to provide safe effective care based on translating scientific evidence into clinical practice. They highlighted that limited evidence to support weight loss interventions in acute settings clashed with their notion of self as a ‘scientist’ so were reluctant to engage in this less researched area of clinical practice. Participants stated that there was clear evidence for interventions such as high protein feeding in critical care or enteral/parenteral nutrition support for malnutrition and therefore, these interventions were judged to fit with dietitians’ professional identity as scientists. Participants reported that feeding patients with obesity was complex, and highlighted inconsistencies in the evidence for energy and protein requirements for this patient group. There was a widely held view that for all patients, weight maintenance is crucial to recover from a critical illness and intensive care admission. Participants working in the intensive care setting reported that an apparent lack of evidence supporting weight management interventions in acute settings, including in the step down from the intensive care phase, was a factor in avoiding obesity-related nutrition interventions.

Participants reported that they would need to see that intentional weight loss interventions are effective with high patient adherence in the acute care setting before changing clinical practice. Some participants reported they lacked the counselling and behaviour management skills to effectively manage obesity and would require additional knowledge and skills. Some participants identified that as dietitians, it is important to understand obesity as a disease, this participant describing the complexities in treatment matters. “…need [to] have knowledge around all of the hormones, satiety hormones, and some of the conditions whereby, you know the genetic component, the whole picture and (and) not just understanding the diet component” (Participant 25, Hospital C). A small number of more experienced participants (n = 3) reported there were clinical guidelines and evidence to support non-surgical weight management in the acute setting, focussed on energy intake and improved diet quality over time, and acknowledged these were rarely adopted.

Acknowledgement of weight bias and stigma

Overall, participants acknowledged the weight bias and stigma potentially felt by their patients living with obesity. Many participants expressed reluctance to engage in conversations about weight because of this. Barriers to instigating conversations about weight included a lack of confidence and conversational skill in this area, fear of patients being rude or disagreeable and a concern that their professional role could contribute to weight stigma. Participants reported that they did not have conversations with patients about the impact of obesity on health and were silent on this during nutrition consultations; rather they focussed on eating for recovery. Other participants stated that paradigms like Health At Every Size [43], and ’no diet’ approaches taught as part of dietetic training, increased their reluctance to enter into a dialogue about the links between weight and health outcomes. Some participants reflected that with years of experience, their confidence in initiating respectful discussions about weight improved. These participants felt it was important to respectfully address both the stigma and challenges of obesity: “I think it is important to bring it up and explain the benefits to them even though it can be confusing for them too” (Participant 25, Hospital B).

Participants also described other clinicians’ bias related to nutrition care. Participants reported that although they advocated for early initiation of nutrition support, patients with obesity may experience delayed access and longer periods of suboptimal nutrition with common rationale for this from treating medical teams being, “this patient has more reserves” (Participant 15, Hospital A). Participants were concerned about an inequity of access to nutrition care but felt this was out of their locus of control to manage. A small number of participants reported that advocacy for earlier initiation of nutrition support requires dietitians to take on the role of professional educator: “. it has taken a long time educating them [surgeons] around the importance of nutrition provision irrespective of body mass index” (Participant 25, Hospital B).

Dietitian-led care

This category relates to participants’ views on patient- versus dietitian-led care and how this influences the scope of acute nutrition care for people living with obesity. All participants reported that they had experiences of providing nutrition care to patients living with obesity and this was an increasingly common presentation. Participants spoke about the importance of practising patient-centred care and often expressed deep empathy for patients with obesity. Contradistinctively, participants reported that they did not often engage patients in the planning of nutrition care or goal setting, feeling a need to prioritise clinician goals over patient goals due to the acute illness: “I tend to come at them more with the evidence based of like why we’re here to see them and what our goal is” (Participant 13, Hospital B). Participants identified that some patients with obesity expressed a desire to focus on weight reduction during their acute admission. In these instances, participants disagreed with the patient, describing that it was unsafe to do in the context of an acute illness, emphasizing the main goal of nutrition intervention be on weight maintenance, due to its importance for recovery from acute illness. Participants acknowledged this may be a lost opportunity for engaging patients who are ready to make a change.

Hospital systems: referral, triage, food, and equipment

This category describes the systems, tools, and processes that acute clinical dietitians work within to deliver nutrition care and their influence on limiting weight management in acute settings. Referral systems included malnutrition risk screening tools, electronic and verbal referrals from multidisciplinary meetings. Participants reported receiving referrals from medical, nursing, and allied health colleagues for patients with obesity where the referral reason was often not for weight management but other acute nutrition issues. Many participants reported their medical team valued their expertise in weight management, evidenced by ongoing referrals for this clinical issue. Although in contrast to the culture of not managing this issue in the acute setting, participants often felt professionally devalued with late timing for referrals related to weight management; often received on the day of hospital discharge.

Many participants reported they referred patients for weight management to primary care services, expressing frustration with poorly coordinated systems of referral. Systems were reliant on other health professionals to make the referral or the patient to self-refer to community dietitians. Participants were unaware if the referrals were actioned and did not seek confirmation of referral outcomes. Participants reflected that this was a poor transition of care but were unable to rectify due to their workload demands. Participants expressed a desire for clear pathways and enhanced transitions of nutrition care beyond the acute setting for patients living with obesity.

Senior dietitian and dietetic manager participants were unable to identify the evidence used to develop triage tools in clinical settings. They reported the tools were used to support decision making to prioritise certain conditions and acknowledged that this limited care to specific patient groups, including those with obesity. Weight management was listed as a low-risk issue in the tools used by all participants. Malnutrition risk screening tools were universally used, and people at high risk of malnutrition were referred to dietitians via automated systems. Some participants felt that these screening tools were not fit for purpose for patients in the obesity weight classifications, raising concern that these groups of patients are often missed in the screening process.

Participants described that the food systems and inpatient ward environments were additional barriers to providing dietetic care to patients living with obesity. Several participants reported that in some hospitals there were limited options for healthy, contemporary therapeutic menus to support weight management, and described obesogenic hospital environments with access to cheap, unhealthy, and processed foods and limited options for physical activity. Participants reported hospitals often provided limited support to care for people in obesity weight classifications due to a lack of equipment such as beds, chairs, or mobility aids to cater for higher body weights.

Discussion

The theory of limiting obesity-related nutrition care and the five related categories developed in this constructivist grounded theory study offer important insights into factors shaping the lack of nutrition care regarding weight management for people living with obesity in acute hospital settings. Previously, there was limited research into the clinical judgement and decision making of dietitians in acute care hospitals [44, 45]. Our study indicates that acute nutrition care planning for people with obesity is influenced by professional, cultural, system and environmental factors.

Clinical judgement is used to make complex prioritisation decisions that involve comparing the degree of risk and need among patients within a clinical workload. Health services often implement clinical triage systems to allocate resources, prioritise referrals and manage individual workloads [46] with a focus on patient safety and risk. Prioritisation tools were widely used, and our participants admitted that these tools may not be consistently evidence informed. This aligns with several studies finding limited evidence supporting the clinical categories [44] and the reliability and validity of dietetics prioritisation and triage tools [47]. Given the lack of evidence in the development and evaluation of these tools, the high compliance and utilisation observed amongst participants seems incongruent with their conviction to evidence based dietetic practice.

Our study found that dietitians in the acute setting strongly focus on prevention and treatment of malnutrition, a health care concern that can result in poor patient outcomes, increased length of stay and hospital costs [48]. A hospital acquired complication, clinical governance and quality systems identify malnutrition risk and monitor rates of malnutrition across European and Australian hospitals [49,50,51]. There is evidence that meeting hospital key performance indicators can influence clinical judgement and decision making related to both the types of patients and interventions chosen [52, 53]. Although these governance factors may improve care outcomes for patients with malnutrition, they may be to the detriment of other reversible diseases such as obesity which are currently deprioritised in acute care settings.

Clinical decision making involves the integration of evidence-based and experienced-based knowledge to make decisions that is best for patients [45]. In our study, we found limited awareness of the existence of best practice clinical guidelines for obesity management, especially for acute care or critically ill patients. This is consistent with recent findings in a study with Australian dietitians caring for people living with obesity [54], including dietitians working in public hospitals with dedicated obesity services [54]. This study highlighted skills gaps in counselling and behaviour management required for success in weight management, despite clinical counselling on dietary change being a key strategy for the treatment of people living with obesity [25, 55]. Individualised nutrition consultation with a dietitian has been found to be effective in decreasing weight [24]. Clinical practice guidelines support that people living with obesity should receive individualised medical nutrition therapy provided by a dietitian to improve weight outcomes, waist circumference, glycaemic control, established blood lipid targets, and blood pressure [55, 56].

Previous studies have found that dietitians possess weight bias towards people with obesity [57,58,59], however this was related to negative attitudes and emotions. Our participants reported empathy and sensitivity to patients with obesity yet refrained from providing care. This may be an unconscious attitude that occurs outside of awareness resulting in enacted stigma [60]. Enacted stigma can reduce the quality and quantity of patient-centred care [61]. In our study, this enacted stigma had important implications for communication, with dietitians avoiding conversations about weight with patients, as well as impacting decision making on the type of nutrition intervention implemented. Our participants expressed reluctance to engage with patients about their weight status for fear of how the role of the dietitian will be viewed by the patient and a desire to avoid offence. As implicit attitudes are automatic and in contrast to explicitly held beliefs, it is important to highlight current experiences to reframe and optimise patient care [61]. Strategies that focus on building interpersonal skills [62] to support dietitian-patient relationships, advocacy for patient’s nutritional needs and negotiating interventions with medical practitioners as well as education on shared decision making, bringing together individualised nutrition care [25, 55] evidence-based practice [61] and patient centred care [63], may be of particular benefit. Such strategies should also be considered in dietetic training curricula for the emerging dietetic workforce.

Our study highlighted a barrier to decision making for dietitians in this group of patients related to pathways for ongoing nutrition care in the primary care setting. Acute focused health care systems are ill equipped to manage the range of needs of patients living with complex, chronic health conditions [64] so a systems-based approach across settings is required. Considered discharge care planning can reduce readmission [65], improve the patient experience and support transitions of care [64]. Patients with chronic disease and weight management goals have reported that they lacked support and practical advice post discharge from acute admissions [66]. This highlights a key opportunity for improving future practice, for example, by initiating shared decision-making, informed consent and setting goals of care with patients, their support people, and the multidisciplinary primary care team.

The experiences of our participants in the acute setting, are like those of health care professionals caring for people living with obesity across other settings. Awareness of weight stigma has been acknowledged by multiple health care professionals, with fear of offending patients a key deterrent in engaging in obesity management [67] In primary care, weight stigma affects nutrition care planning for both dietitians and general practitioners [23]. In private practice and primary care, patient centred care is central to dietetic practice [68]; and system barriers, such as referral criteria [23] and funding models [68], have been reported to impede implementation of evidence-based practice.

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of this study include that participants were from four acute hospitals in Melbourne, Australia. Participants were likely motivated to share their perspectives due to their own interest and experiences in the topic. A strength of this study was the methodology and rigour: considered integral to the research process, constructivist grounded theory utilises theoretical sampling techniques [38] for data collection and participant recruitment, acknowledges both researcher bias and involvement, and that findings are embedded within a specific context [29, 34, 35] The resultant theory may need further refinement and could be explored in other contexts/settings; however, the study findings highlight multiple areas for future research and practice that could lead to improvements in acute nutrition care for people with obesity.

Conclusion

The grounded theory developed in this study—limiting obesity-related acute nutrition care—provides new insights into the influences on clinical decision making of dietitians providing nutrition care to patients living with obesity in the acute care setting. The growing prevalence of obesity in hospitalised patients requires consideration of the acute hospital as a setting for initiating weight management interventions. A systems-based approach considering prioritisation and triage tools, clinical care pathways supporting clinical decision making and patient-centred transition of care that integrates available best practice guidelines for obesity management will be needed. This will require a paradigm shift in the culture of professional practice to consider all nutrition care needs of patients living with obesity who are accessing acute hospitals for health care.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request.

References

Buchanan R. Wicked problems in design thinking. Des Issues. 1992;8:5–21.

Parkinson J, Dubelaar C, Carins J, Holden S, Newton F, Pescud M. Approaching the wicked problem of obesity: an introduction to the food system compass. J Soc Mark. 2017;7:387–404.

Inoue Y, Qin B, Poti J, Sokol R, Gordon-Larsen P. Epidemiology of obesity in adults: latest trends. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:276–88.

Elliott A, Gibson S, Bauer J, Cardamis A, Davidson Z. Exploring overnutrition, overweight, and obesity in the hospital setting—a point prevalence study. Nutrients. 2023;15:2315.

Di Bella AL, Comans T, Gane EM, Young AM, Hickling DF, Lucas A, et al. Underreporting of obesity in hospital inpatients: a comparison of body mass index and administrative documentation in Australian Hospitals. Healthcare. 2020;8:334.

Hossain M, Amin A, Paul A, Qaisar H, Akula M, Amirpour A, et al. Recognizing obesity in adult hospitalized patients: a retrospective cohort study assessing rates of documentation and prevalence of obesity. J Clin Med. 2018;7:203.

Korda RJ, Joshy G, Paige E, Butler JRG, Jorm LR, Liu B, et al. The relationship between body mass index and hospitalisation rates, days in hospital and costs: findings from a large prospective linked data study. Van Baal PHM, editor. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118599.

Nguyen AT, Tsai Clin, Hwang Lyu, Lai D, Markham C, Patel B. Obesity and mortality, length of stay and hospital cost among patients with sepsis: a nationwide inpatient retrospective cohort study. Efron PA, editor. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154599.

Dietz WH, Baur LA, Hall K, Puhl RM, Taveras EM, Uauy R, et al. Management of obesity: improvement of health-care training and systems for prevention and care. Lancet. 2015;385:2521–33.

Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change. Lancet Comm Report Lancet 2019;393:791–846.

Hauck K, Hollingsworth B. The impact of severe obesity on hospital length of stay. Med Care. 2010;48:335–40.

Fusco K, Thompson C, Woodman R, Horwood C, Hakendorf P, Sharma Y. The impact of morbid obesity on the health outcomes of hospital inpatients: an observational study. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4382.

Gil JA, Durand W, Johnson JP, Goodman AD, Daniels AH. Effect of obesity on perioperative complications, hospital costs, and length of stay in patients with open ankle fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27:e529–34.

Terada T, Johnson JA, Norris C, Padwal R, Qiu W, Sharma AM, et al. Severe obesity is associated with increased risk of early complications and extended length of stay following coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003282.

Mathieson C. Skin and wound care challenges in the hospitalized morbidly obese patient. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2003;30:78–83.

Bochicchio GV, Joshi M, Bochicchio K, Nehman S, Tracy KJ, Scalea TM. Impact of obesity in the critically Ill trauma patient: a prospective study. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:533–8.

Schetz M, De Jong A, Deane AM, Druml W, Hemelaar P, Pelosi P, et al. Obesity in the critically ill: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:757–69.

Campbell K, Crawford D. Management of obesity: attitudes and practices of Australian dietitians. Int J Obes. 2000;24:701–10.

Ball L, Larsson R, Gerathy R, Hood P, Lowe C. Working profile of Australian private practice accredited practising dietitians. Nutr Diet. 2013;70:196–205.

Markovic TP, Proietto J, Dixon JB, Rigas G, Deed G, Hamdorf JM, et al. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm: a simple tool to guide the management of obesity in primary care. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2022;16:353–63.

Bleich SN, Bandara S, Bennett W, Cooper LA, Gudzune KA. Enhancing the role of nutrition professionals in weight management: a cross-sectional survey. Obesity. 2015;23:454–60.

Barnes PA, Weiss-Kennedy C, Schaefer S, Fogarty E, Thiagarajah K, Lohrmann DK. Perceived factors influencing hospital-based primary care clinic referrals to community health medical nutrition therapy: an exploratory study. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:224–7.

Abbott S, Parretti HM, Greenfield S. Experiences and perceptions of dietitians for obesity management: a general practice qualitative study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2021;34:494–503.

Williams LT, Barnes K, Ball L, Ross LJ, Sladdin I, Mitchell LJ. How effective are dietitians in weight management? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Healthcare. 2019;7:20.

Morgan-Bathke M, Raynor HA, Baxter SD, Halliday TM, Lynch A, Malik N, et al. Medical nutrition therapy interventions provided by dietitians for adult overweight and obesity management: an academy of nutrition and dietetics evidence-based practice guideline. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2023;123:520–545.e10.

Flodgren G, Gonçalves‐Bradley D, Summerbell C. Interventions to change the behaviour of health professionals and the organisation of care to promote weight reduction in children and adults with overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2017;(11). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000984.pub3

Aarts MA, Sivapalan N, Nikzad SE, Serodio K, Sockalingam S, Conn LG. Optimizing bariatric surgery multidisciplinary follow-up: a focus on patient-centered care. Obes Surg. 2017;27:730–6.

Dickerson RN, Andromalos L, Brown JC, Correis MI, Pritts W, Ridley EJ, et al. Obesity and critical care nutrition: current practice gaps and directions for future research. Crit Care. 2023;27:177.

Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312118822927.

Charmaz K. Constructivist grounded theory. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12:299–300.

Grundmann R. Climate change as a wicked social problem. Nat Geosci. 2016;9:562–3.

Amin C, Sukamdi S, Rijanta B. Exploring migration hold factors in climate change hazard-prone area using grounded theory study: evidence from Coastal Semarang, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021;13:4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084335

Chilton M, Knowles M, Bloom SL. The intergenerational circumstances of household food insecurity and adversity. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12:269–97.

Bryant A, Charmaz K. The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory [Internet]. London, UNITED KINGDOM: SAGE Publications, Limited; 2019. Available from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/monash/detail.action?docID=5755099

Charmaz K, Thornberg R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18:305–27.

Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2015;15:219–34.

Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley C, Stevenson F. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:26–44.

Butler AE, Copnell B, Hall H. The development of theoretical sampling in practice. Collegian. 2018;25:561–6.

Lingard L, Albert M, Levinson W. Grounded theory, mixed methods, and action research. BMJ. 2008;337:a567.

Vann-Ward T, Morse JM, Charmaz K. Preserving self: theorizing the social and psychological processes of living with Parkinson Disease. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:964–82.

Elliott A, Gibson S. Exploring stakeholder experiences of dietetic service and care delivery: a systematic qualitative review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023;36:288–310.

Roberts RE. Qualitative interview questions: guidance for novice researchers. Qual Rep. 2020 Sep;25:COV1+.

Penney TL, Kirk SFL. The health at every size paradigm and obesity: missing empirical evidence may help push the reframing obesity debate forward. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e38–42.

Hickson M, Davies M, Gokalp H, Harries P. Using judgement analysis to identify dietitians’ referral prioritisation for assessment in adult acute services. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:1291–6.

Vo R, Smith M, Patton N. The role of dietitian clinical judgement in the nutrition care process within the acute care setting: a qualitative study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2021;34:124–33.

Harding K, Taylor N, Shaw-Stuart L. Triaging patients for allied health services: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Occup Ther. 2009;72:153–62.

Porter J, Jamieson R. Triaging in dietetics: do we prioritise the right patients? Nutr Diet. 2013;70:21–6.

Gomes F, Emery PW, Weekes CE. Risk of malnutrition is an independent predictor of mortality, length of hospital stay, and hospitalization costs in stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:799–806.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (second edition) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/national-safety-and-quality-health-service-standards-second-edition

Cass AR, Charlton KE. Prevalence of hospital‐acquired malnutrition and modifiable determinants of nutritional deterioration during inpatient admissions: a systematic review of the evidence. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35:1043–58.

Cortés-Aguilar R, Malih N, Abbate M, Fresneda S, Yañez A, Bennasar-Veny M. Validity of nutrition screening tools for risk of malnutrition among hospitalized adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2024;43:1094–116.

Rodziewicz TL, Houseman B, Hipskind JE. Medical error reduction and prevention. [Updated 2023 May 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL); Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499956/

McGinnis PQ, Hack LM, Nixon-Cave K, Michlovitz SL. Factors that influence the clinical decision making of physical therapists in choosing a balance assessment approach. Phys Ther. 2009;89:233–47.

Clarke ED, Haslam RL, Baldwin JN, Burrows T, Ashton LM, Collins CE. Survey of Australian dietitians contemporary practice and dietetic interventions in overweight and obesity: an update of current practice. Dietetics. 2023;2:57–70.

Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J J de l’Assoc Med Can. 2020;192:E875–91.

Hassapidou M, Vlassopoulos A, Kalliostra M, Govers E, Mulrooney H, Ells L, et al. European Association for the study of obesity position statement on medical nutrition therapy for the management of overweight and obesity in adults developed in collaboration with the European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians. Obes Facts. 2022;16:11–28.

Diversi TM, Hughes R, Burke KJ. The prevalence and practice impact of weight bias amongst Australian dietitians. Obes Sci Pract. 2016;2:456–65.

Budd GM, Mariotti M, Graff D, Falkenstein K. Health care professionals’ attitudes about obesity: an integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:127–37.

Panza GA, Armstrong LE, Taylor BA, Puhl RM, Livingston J, Pescatello LS. Weight bias among exercise and nutrition professionals: a systematic review: weight bias in exercise and nutrition. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1492–503.

Prunty A, Hahn A, O’Shea A, Edmonds S, Clark MK. Associations among enacted weight stigma, weight self-stigma, and multiple physical health outcomes, healthcare utilization, and selected health behaviors. Int J Obes. 2023;47:33–8.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16:319–26.

Puhl RM, Phelan SM, Nadglowski J, Kyle TK. Overcoming weight bias in the management of patients with diabetes and obesity. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34:44–50.

Desroches S, Lapointe A, Deschênes SM, Gagnon MP, Légaré F. Exploring dietitians’ salient beliefs about shared decision-making behaviors. Implement Sci. 2011;6:57.

Kuluski K, Hoang SN, Schaink AK, Alvaro C, Lyons RF, Tobias R, et al. The care delivery experience of hospitalized patients with complex chronic disease. Health Expect. 2013;16:e111–23.

Fusco K, Robertson H, Galindo H, Hakendorf P, Thompson C. Clinical outcomes for the obese hospital inpatient: an observational study. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:2050312117700065.

Longman JM, Rix E, Johnston JJ, Passey ME. Ambulatory care sensitive chronic conditions: what can we learn from patients about the role of primary health care in preventing admissions? Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24:304–10.

Jeffers L, Manner J, Jepson R, McAteer J. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and experiences of obesity and overweight and its management in primary care settings: a qualitative systematic review. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2024;25:e5.

Harper C, Seimon RV, Sainsbury A, Maher J. “Dietitians may only have one chance”—the realities of treating obesity in private practice in Australia. Healthcare. 2022;10:404.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.E. and S.G.; methodology: A.E. and S.G.; data curation: A.E.; formal analysis: A.E., S.G. J.B. C.M.; writing—original draft preparation: A.E.; writing—review and editing: A.E., J.B., C.M., and S.G.; visualization: A.E. and S.G.; supervision: S.G. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elliott, A., Bauer, J., McDonald, C. et al. Exploring dietitians’ experiences caring for patients living with obesity in acute care: a qualitative study. Int J Obes 49, 698–705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01697-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01697-y