Abstract

Objective

To develop a weight management nutrition knowledge questionnaire for Chinese adults (C-WMNKQ) and to test its reliability and validity.

Methods

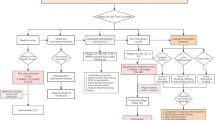

We evaluated the content validity of the questionnaire using the expert consultation method, evaluated the face validity of the questionnaire through a pre-survey, eliminated the questions that did not meet the criteria through item difficulty, item differentiation, and inter-item correlation. We verified the construct validity using the known-groups comparison method. Correlation analysis by comparing it with the general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for Chinese adults (C-GNKQ) was conducted for criterion validity evaluation. The internal consistency reliability, split-half reliability, and test–retest reliability validation were also evaluated, and relevant evidence of expected convergent validity was obtained.

Results

The final C-WMNKQ contains 39 items in 5 dimensions. The overall internal consistency of the C-WMNKQ was 0.808 for Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, 0.81 for ω coefficient, 0.788 for Guttman’s coefficient, 0.843 for Spearman’s correlation coefficient, and 0.908 for overall ICC (95% CI = 0.870–0.935). Meeting the criterion of structural validity, nutrition professionals scored 26.3% higher than those in the financial field, p < 0.001. The correlation coefficient between the total C-WMNKQ score and the total C-GNKQ score was 0.641, p < 0.001, which is good for criterion validity. In terms of convergent validity, the level of nutrition knowledge of women was higher than that of men, the partial nutrition knowledge score of participants aged 35–54 years old was significantly higher than that of participants aged 18–34 years old, the level of nutrition knowledge of those with higher education was higher. Participants with per capita monthly household income >8000RMB had significantly higher partial nutrition knowledge scores than those with <3000RMB and 3000–5000RMB.

Conclusions

C-WMNKQ has good reliability and validity and can be used as a valid tool to assess the nutrition knowledge of Chinese adults related to weight management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Body weight is an important indicator of physical health, and maintaining a normal body weight plays an important role in physical health. Body mass index (BMI) as a method of assessing obesity, which is calculated by weight (kg)/[height (m)]2. Currently, the recommended standard in China is that adults with BMI <18.5 are considered underweight, and overweight and obesity are diagnosed for 24.0 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 28.0 and BMI ≥ 28.0 kg/m2 [1]. Nowadays, people are increasingly pursuing a healthy lifestyle and improving their competitiveness in society through good weight management [2], but the current status of weight management is not optimistic. Obesity has now become a global public health crisis. Up to 2020, there are more than 300 million adults with obesity in the world, and according to the development of this trend, it is expected that the number of people with obesity in the world will reach 1.1 billion by 2030 [3]. According to the Report on Nutrition and Chronic Disease Status of Chinese Residents (2020), the prevalence of overweight or obesity among urban and rural residents of all ages in China has continued to rise, and more than one-half of adult residents suffer from overweight or obesity.

Overweight, obesity and chronic diseases caused by them are closely related to poor dietary factors, unhealthy dietary behaviors and habits. Numerous studies have shown that nutritional knowledge greatly influences people’s food choices, dietary behaviors and habits, and dietary quality [4, 5]. Individuals with higher levels of nutrition knowledge use nutrition facts labels more frequently [6], are more likely to reduce salt intake and make healthier food choices, and have higher diet quality [7]. However, the current state of nutrition knowledge level is that people generally have insufficient nutrition knowledge base. A cross-sectional multinational study abroad investigated 8191 subjects from Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan [8], and found that the majority of study participants (73.1%) had inadequate nutrition knowledge. The Nutritional Health Knowledge Questionnaire for the Chinese adult residents is used as a tool for assessment in many parts of the country. It was found to have a nutritional health knowledge rate of 56.1% among residents aged 18–64 years in Hainan Province in 2021 [9], whereas the rate for the same type of residents in Shanghai during the same time period was 35.78% [10], in Sichuan Province it was 16.89% [11], and in Guizhou Province, it was 5.5% [12]. Based on this current situation, the World Health Organization (WHO) has made the popularization of nutritional health knowledge one of its top priorities [13]. In the programmatic documents such as the “Healthy China 2030” Plan Outline and the Healthy China Action (2019–2030), our government has clearly pointed out that it is necessary to “strengthen nutritional health education and increase the rate of residents’ knowledge of nutritional health” [14, 15].

Abnormal weight management may reflect an inadequate understanding of important nutrition principles and relevant nutrition knowledge, so it is critical to understand the relationship between nutrition knowledge and weight management, but the relationship is largely unexplored, with most nutrition knowledge questionnaires examining only general nutrition knowledge. To assess whether nutrition knowledge related to weight management predicts successful long-term weight management, in 2020 Michael Jensen and others [16] at the Mayo Clinic in the USA developed the Weight Management Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire (WMNKQ), combined questionnaire entries from the general nutrition knowledge questionnaire GNKQ [17], as well as content from the nutrition and weight health related programs from the NHLBI [18], the CDC [19], the Center for Patient Education at the Mayo Clinic, and the USDA [20]. WMNKQ has been developed through correspondence with authoritative experts and has been shown to have good reliability and validity. Most of the existing questionnaires for measuring nutrition knowledge among Chinese adults have not been tested for reliability and validity, and these questionnaires mainly focus on declarative knowledge, with less measurement of procedural knowledge (e.g., the application of knowledge). As China lacks a scientifically standardized assessment tool for nutrition knowledge on weight management, and based on the background that more than half of Chinese adults belong to the group with overweight and obesity, it is necessary to introduce the WMNKQ and revise it in Chinese with the cultural background of China, so that it can become a powerful tool for investigating the nutrition knowledge level of Chinese adults in weight management. Previous studies have mainly adapted the questionnaire by adding items about national dietary policies and replacing uncommon foods in the original questionnaire with local foods [21]. Following standardized translation methods and guidelines, this study incorporated traditional Chinese dietary patterns and dietary recommendations based on the original questionnaire, aimed to develop a weight management nutrition knowledge questionnaire for Chinese adults (C-WMNKQ) and to test its reliability and validity.

Methods

Introduction of the questionnaire

The WMNKQ was designed for adults, and the questionnaire consisted of 43 items in 5 dimensions: energy density (19 items), portion size (15 items), variety of food affects food intake (2 items), reliable nutrition information source (2 items), alcohol intake and sugar sweetened beverages (5 items). The total score is expressed as a percentage of correctness, i.e., number of items answered correctly/total number of items × 100%, with a higher total score indicating a higher level of nutrition knowledge for weight management. Although other nutrition knowledge questionnaires have addressed questions related to weight management, the WMNKQ has the advantage of including the five dimensions related to weight management mentioned above, and the fact that the questionnaire was evaluated for item difficulty, item discrimination, item-to-item correlation analysis, criterion validity, and convergent validity, in addition to the usual construct validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency validation, which resulted in a more rigorous evaluation of the WMNKQ than the existing questionnaires for nutrition knowledge in general.

Cross-cultural adaptation process of the questionnaire

Firstly, we obtained the consent and formal authorization from the original author of WMNKQ, Michael Jensen, by e-mail, and then we conducted cross-cultural adaptation according to the “Brislin Translation-Back translation Method” [22] and the Recommended Guidelines [23], and we went through the process of direct translation, synthesis, back-translation, review by the original author, expert committee, and pre-survey to translate WMNKQ into the Chinese version.

Direct translation, synthesis, back-translation, and review by the original author

The translation was carried out independently by two native Chinese speakers with good English background, one of whom was a graduate student in nursing and the other was a graduate student in English with no medical background. The two directly translated versions were then compared with the WMNKQ by members of the research group, and differences and inconsistencies were discussed and finally agreed upon to form the initial translated version, the synthesized version Z1. Then the version Z1 was independently back-translated into English by two postgraduate students who are currently studying in the U.K, and they have not been exposed to the original questionnaire (one postgraduate student of Nursing, and the other one of Economics). The final English back-translated version was verified through discussion and verification by the research group. We emailed both the synthesized version of Z1 and the English back-translated version to Michael Jensen for review and consultation on any ambiguities or disagreements encountered during the translation process. Since artichokes are not common in China and we do not use fluid ounces as a unit of measurement, we deleted Question 20 (Do you think artichoke contain fiber?) and Question 27 (How many fluid ounces are in one cup?) from the original questionnaire, which was also approved by Michael Jensen. Finally, we synthesized Michael Jensen’s comments and the discussion results of the group members to form the first draft of the Chinese version of Z2.

Committee of experts and content validity evaluation

An expert committee was formed, consisting of 14 physicians and nurses (4 nutritionists, 3 endocrinologists, 6 nutritional nurse specialists, and 1 diabetes-specialized nurse) from the department of nutrition or endocrinology, with the title of associate senior or above, and ≥10 years of working time. Content validity evaluation was measured by the item-level content validity index (I-CVI) at all item levels and the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI/Ave) at the average scale level. The panel used a 4-point Likert scale to assess the relevance of each item to the study topic, with 1 point indicating “not relevant at all”, 2 points indicating “must be modified or not relevant”, 3 points indicating “relevant, but needs minor modification”, and 4 points indicating “very relevant”. The algorithm of I-CVI is the ratio of the number of experts who scored 3–4 to the total number of experts for each item, while the algorithm of S-CVI/Ave is the mean of I-CVI for all items. Generally, I-CVI ≥ 0.78 and S-CVI/Ave ≥ 0.90 were considered acceptable criteria [24]. The items with divergence or discrepancy were adjusted and modified according to the experts’ opinions to form the first draft of the Chinese version of Z3, which included 41 items with 5 dimensions.

Pre-survey and face validity evaluation

A pre-survey was conducted on the Chinese version of Z3. Convenience sampling was used to select at least 20 participants to complete the questionnaire, ensuring that they were ≥18 years old and had normal reading, writing and comprehension skills. The purpose and requirements for completing the questionnaire were explained to the participants before the survey, and the questionnaire was distributed after obtaining consent. During the completion process, participants’ understanding of the questionnaire items was obtained.

Reliability and validity test of the questionnaire

Reliability and validity test methods

Item analysis

-

(1)

Item difficulty: item difficulty is the percentage of subjects who answered the item correctly, with smaller values demonstrating that the item is more difficult and vice versa the easier it is. Values between 0.1–0.9 are acceptable, questions <0.1 or >0.9 have limited value and should be discarded [25]. Since the authors of the WMNKQ believed that the population of Olmsted County they tested had higher than expected health literacy and should also have higher than average nutrition knowledge, a range of 0.3–0.9 was used. Previous studies have shown that Chinese people generally have inadequate nutrition knowledge [9,10,11,12], so a range of 0.1–0.9 was used in this study.

-

(2)

Item discrimination: item discrimination is used to test the discrimination of the same scale to different study subjects, mostly by using the item discrimination index. Since all the items in this study are dichotomous variables, the point-two column correlation method can also be used [16, 26, 27]. Our study combines these two methods for item discrimination evaluation.

-

(1)

Item discrimination index (D value): all subjects were ranked in descending order of total score, with the top 27% of the total score being the high group and the bottom 27% being the low group, and the correctness of the two groups for each entry response was calculated separately, with the D-value being the difference between the correctness of the high group and the correctness of the low group [28]. D value takes a range of −1.00–1.00. When D value is negative, it indicates that the item does not have the degree of discrimination, consider deleting; when D value is positive, the larger the value indicates that the item has a higher degree of discrimination. The general recommendation is that D value needs to be >0.2 [29]. For a test tool with good discrimination, its value of item difficulty is about 0.5, indicating that the tool with moderate difficulty has the highest discrimination index [30].

-

(2)

Point-two column correlation method: Michael Jensen et al. [16], Kline [26], and Gao et al. [27] all believed that the item-total score correlation coefficient should be greater than 0.2, so our study also used this as a criterion.

-

(1)

-

(3)

Inter-item correlation: the consistency of scores between every two items in the questionnaire was calculated. Questions with correlation coefficients >0.9 were labeled as potentially redundant and needed to be excluded [26].

Construct validity

The known-groups comparison method was used to evaluate the construct validity, which tested whether the assessment tool could differentiate the level of nutrition knowledge of the study participants [16, 27]. In this study, nutrition-related professionals and people in the financial field were selected for comparison. These two groups have similar literacy levels, but may have different levels of nutrition knowledge due to the nature of their occupations.

Criterion validity

It refers to the degree of proximity between the questionnaire measurement and the validity criteria. The higher the correlation coefficient between the questionnaire to be developed and the validity criterion questionnaire, the better. Between 0.4–0.8 indicates moderate correlation and >0.8 indicates high correlation [31]. The C-GNKQ [27] was proposed to be used as a validity criterion instrument in this study.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity was used to assess whether the expected correlation exists between the instrument response and the different demographic variables of the group. If the expected correlation is observed between factors such as gender, age, education and nutrition knowledge assessed through the questionnaire, it proves that the questionnaire has some convergent validity [16]. It was hypothesized that females would have higher nutrition knowledge scores than males [32,33,34], younger participants would have higher nutrition knowledge scores [16, 33], participants with higher levels of education would have higher nutrition knowledge scores [16, 27, 34], participants with higher levels of income would have higher nutrition knowledge scores [27, 34], and participants residing in towns and cities would have higher nutrition knowledge scores than those residing in rural areas [35, 36].

Reliability

The internal coherence of the questionnaire was tested using internal consistency reliability and split-half reliability, and the stability of the questionnaire was tested using retest reliability.

-

(1)

Internal consistency reliability: by calculating the Cronbach’s α and the ω coefficient of the questionnaire, if the coefficient is >0.70, it means good reliability; if the coefficient is >0.60, it means acceptable reliability [37].

-

(2)

Split-half reliability: in split-half reliability, all the items are divided into two halves by odd and even items, and the reliability of each of the two parts is calculated. If the split-half reliability Guttman coefficient >0.60, it indicates that the assessment results are reliable [31].

-

(3)

Test–retest reliability: the degree of consistency in the results obtained when the same instrument is used twice to measure the same group of research subjects. The general time for retesting is 2 weeks after the previous survey. The higher the test–retest reliability, the better the stability of the research instrument. In this study, the following two methods were used for measurement: (1) Spearman correlation: the coefficient should be >0.70 [37]; (2) Intraclass correction coefficient (ICC): ICC value should be >0.75 [38].

Participants and ethics

In this study, electronic questionnaires were used to generate web links to the questionnaires through an online survey platform called “Questionnaire Star”. There were three participant samples in this study. Sample A was used for the pre-survey and included at least 20 adults, based on the sample size required for the pre-survey. Sample B was used to test item analysis, criterion validity, convergent validity, internal consistency reliability, and split-half reliability: according to the principle that the sample size should satisfy the number of scale items by a factor of 5–10 times, the preliminary Chinese version of the Z3 had a total of 41 items, and considering 20% of invalid questionnaires, the final estimated sample size was 246–492 cases. Sample C was used to test construct validity and retest reliability: in order to determine the appropriate sample size for the average comparison between groups, statistical efficacy analysis was performed. Calculated by G-Power software [39], considering two-tailed independent samples t-test, using mean estimation, taking the medium effect size Effect size = 0.5, common value of significance level α = 0.05, and statistical efficacy Power = 0.8, the minimum sample size for each group was calculated to be 64, and an effect size of d = 0.80 was obtained.

The study was ethically approved and consented by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China (Approval No.: Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital Ethical Review 2023 Research No. 0619), and the participants gave informed consent to participate in this study voluntarily. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Survey tools

General information questionnaire

It was self-designed by reviewing the literature [9,10,11,12, 16, 27], including information on gender, age, ethnicity, height, weight, marital status, place of residence, education level, occupation, economic income.

Chinese version of WMNKQ preliminary draft Z3

C-GNKQ: The general nutrition knowledge questionnaire (GNKQ), the most widely used nutrition knowledge questionnaire, was first developed and compiled in the UK by Parmenter and Wardle [17], and subsequently successfully revised in Australia [40], Turkey [41], the USA [42], the UK [33], Uganda [43], and Japan [21]. GNKQ was revised by Gao et al. [27] in 2021 in Chinese. C-GNKQ consists of 68 items on 4 dimensions: dietary recommendations, source of nutrients, daily food choice, and diet-disease relationship. The survey uses three response types: yes, no, or don’t know. Correct answers are counted as 1 point and incorrect or unknown answers are counted as 0. Each item is scored 1 point for a total score of 0–68. The overall internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.885, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each dimension are 0.563, 0.814, 0.334, and 0.771, and the test–retest reliability was 0.769. The overall reliability and validity is good.

Scoring system

The correct answers to the questionnaire are provided in the supplementary information. Correct answers are scored 1 point and incorrect answers are scored 0 points for a total of 0–41 points, with correctness being the percentage of correct answers.

Statistical analysis methods

SPSS 26.0 was used to analyze the data, and the answers to the items of each questionnaire were transformed into dichotomous data (1 = answered correctly, 0 = answered incorrectly). Measures that conformed to normal distribution were expressed as mean and standard deviation, those that did not conform to normal distribution were expressed as median and quartiles, and count data were expressed as number of cases and percentage. For demographic data comparing the two groups, differences were analyzed using the chi-square test and the nonparametric rank sum test (Mann–Whitney U test). For continuous variables (total score and scores on each dimension), the homogeneity of variance of the two groups was tested by Levine’s test of variance equivalence, and the independent samples t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for analysis. In the case of a significant one-way ANOVA, post hoc tests were conducted using the Bonferroni correction method and the Tamhane’s T2 method. Two-sided tests were used for all analyses, with p < 0.05 indicating a statistically significant difference.

Results

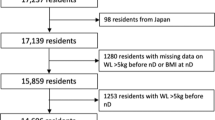

Demographic information

Sample B consisted of 590 adults, predominantly female (80.0%), with age Median (M25, M75) of 28(24, 37) years, BMI Median (M25, M75) of 21.2(19.3, 23.4), 91.3% of the participants had a Bachelor’s Degree or higher. The general demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Content validity

In this study, except for the original questionnaire Question 12 (Do you think raspberries contain fiber?), which had an I-CVI of 0.64, and Question 13 (Do you think Bananas contain fiber?) and Question 28 (Which of these is a good strategy to help to lose weight?), which had an I-CVI of 0.71, the I-CVIs of the remaining 38 items were all greater than 0.78, and the S-CVI/Ave = 0.92, which was greater than 0.90. Considering the overall findings, the content validity index of the questionnaire was still acceptable, and the three items were modified. In Question 12, the word “raspberry” was changed to “strawberry”. In Question 13, some experts suggested that bananas are low in dietary fiber, but after discussion, it was considered that it is meaningful to know that bananas have dietary fiber even though they are low in content, so they were retained. In Question 28, in response to the experts’ question of whether the number or type of foods examined is not clear, the questionnaire was modified. The experts’ general perception of the types and amounts of food differed from the questionnaire content, while Michael Jensen pointed out that more food types in terms of quantity were important contributors to excess energy intake [16]. Retaining this item contributes to the understanding of the concept that food variety influences food intake.

Face validity

Sample A eventually included 55 adults. Most of the questionnaire items were fully understood, and some items that were semantically ambiguous or unclear were modified. The stem of the original Question 25, “Which of these is too large of a serving size for a protein food?” was changed to “Which of the following foods is too large a portion for the amount of protein it contains?”, and “2 tael” was replaced with “85 g” in option A. In option B of the original Question 40 (Which of these has the fewest calories?), we replaced “soda” with “soda carbonated beverage”. The modifications enhanced the face validity of the questionnaire by increasing the percentage of correct responses from 34.6% in the pre-survey to 44.7% for the original Question 25 and from 16.6% in the pre-survey to 44.4% for the original Question 40.

Item analysis

Item difficulty

The item difficulty value for all items ranged from 0.11–0.97, and none of the questions were considered too difficult (<0.1) except for the original Question 13 (Do you think Bananas contain fiber?) and Question 16 (Do you think broccoli contain fiber?), which had >0.9 and were considered too easy. These two questions were deleted and the mean value of the whole questionnaire after deletion was M = 0.57, SD = 0.20, indicating that the questionnaire was moderately difficult and had good discrimination.

Item discrimination

(1) The discrimination index (D-value) of each entry was −0.13–0.76, and all items were positive except for the original Question 28 (Which of these is a good strategy to help to lose weight?). Among all the positive items, D-value of Question 1 (Which of the following single, standard size cups of yogurt for breakfast would be a better choice for weight loss?), Question 13, Question 16, and Question 17 (Do you think green peas contain fiber?) were <0.2. (2) All items were significantly correlated with the total scores, except for the original Question 1. The coefficients of the point-two column correlations of the original Question 6 (If you are working to lose weight and are on vacation where two different breakfast buffet styles are available. Buffet A offers a variety of fruits and whole grain bakeries. Buffet B offers a variety of fruits, pastries, dairy products, deli meats, and whole grain bakeries. Which choice will make it easier to keep your calorie intake lower?), Question 17, and Question 28 were less than 0.2, and only Question 28 was negatively correlated with the total score.

Inter-item correlation

No correlation between the scores of any two items was greater than 0.9, and no items needed to be deleted.

In summary, for all of the above items that did not meet the criteria for item analysis (the original Questions 1, 6, 13, 16, 17, and 28), Question 13 and 16 were deleted, and the remaining items were retained: (1) Question 1 examined energy density through the form of food labels. Food labels provide information about the nutrient content of a food, and the ability to understand this information somewhat influences dietary choices [6]. The Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents 2022 also recommends “learning to read food labels” [44]. (2) Michael Jensen was consulted about the possibility of combining the green peas in the original Question 17 with the lentils in Question 18, and he pointed out that it was necessary to understand the dietary fiber content of each of the two types of legumes separately, so Question 17 was retained, and it can also be contrasted with Question 18. (3) The original Questions 6 and 28 both belonged to the conceptual dimension of food variety influencing food intake, which was proven to be relevant to weight management and should not be deleted.

Construct validity

Sample C consisted of 168 adults (91 nutrition professionals and 77 finance professionals) whose demographics are shown in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in demographic variables except for sex and BMI. Both nutrition professionals and finance professionals were predominantly female, with a majority of normal BMI. The results showed that the overall percentage of correct scores was 72.5% (95% CI = 69.5%–75.6%) for nutrition professionals and 46.2% (95% CI = 43.1%–49.2%) for finance professionals, with an overall difference of 26.3% (p < 0.001). Except for the dimension “Variety of food affects food intake”, nutrition professionals scored significantly higher (p < 0.001) than finance professionals on the total questionnaire score and other dimensions, as shown in Table 3.

Criterion validity

The C-WMNKQ and C-GNKQ were measured simultaneously for the 590 respondents in Sample B. The results of the Pearson correlation analysis showed that the correlation coefficient between the total C-WMNKQ score and the total C-GNKQ score was 0.641(p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.594–0.684), and that the correlation coefficients with the scores on the four dimensions of the C-GNKQ: dietary recommendations, source of nutrients, daily food choice, and diet-disease relationship, were 0.491(p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.425–0.551), 0.609(p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.558–0.654), 0.433(p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.372–0.495), and 0.487(p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.428–0.542), all of which showed significant positive correlations. The criterion validity of the questionnaire was good.

Reliability

Internal consistency reliability and split-half reliability

The overall internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.808, the ω coefficient was 0.81, and the coefficients for the overall and dimensions are shown in Table 4.The items above the overall reliability after deletion of the items were the original Question 1 (0.814), Question 6 (0.810), and Question 28 (0.816), and the reasons for the retention of these three items have been discussed before. The overall split-half reliability Guttman coefficient was 0.788.

Test–retest reliability

A total of 168 people (91 nutrition professionals and 77 finance professionals) completed the pre-test questionnaire, of whom 129 (65 nutrition professionals and 64 finance professionals) completed the post-test questionnaire 2 weeks later, a shedding rate of 23.2%. The Spearman correlation coefficient for the total score of the pre- and post-tests was 0.843, p < 0.001; the overall ICC value of the questionnaire was 0.908 (95% CI = 0.870–0.935), which met the criteria for retest reliability, as shown in Table 5.

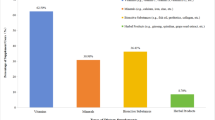

Convergent validity

Gender

Except for Alcohol intake and sugar sweetened beverages, there was a significant difference between genders on the total score and the other dimensions. The independent samples t-test showed that on Variety of food affects food intake, females (M = 0.77, SD = 0.66) scored significantly lower than males (M = 0.97, SD = 0.71), t = −2.964, p = 0.003, 95% CI = 0.069–0.342, d = 0.291. On Total score (Female: M = 22.57, SD = 5.99; Male: M = 20.63, SD = 6.65. t = 2.892, p = 0.004, 95% CI = 0.616–3.265, d = 0.307), Energy density (Female: M = 10.57, SD = 2.69; Male: M = 9.75, SD = 3.02. t = 2.886, p = 0.004, 95% CI = 0.262–1.378, d = 0.287), Portion size (Female: M = 7.58, SD = 2.74; Male: M = 6.75, SD = 2.75. t = 2.945, p = 0.003, 95% CI = 0.277–1.384, d = 0.302), Reliable nutrition information source (Female: M = 1.26, SD = 0.75; Male: M = 0.94, SD = 0.89. t = 3.623, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.147–0.498, d = 0.389), females all scored significantly higher than males. See Fig. 1.

Age

There were significant differences between participants in different age groups on Variety of food affects food intake (F = 3.764, p = 0.024, η2 = 0.013) and Alcohol intake and sugar sweetened beverages (F = 3.509, p = 0.031, η2 = 0.012). The Bonferroni correction method showed that on Variety of food affects food intake, participants aged 35–54 years (M = 0.92, SD = 0.72) scored significantly higher than those aged 18–34 years (M = 0.76, SD = 0.65), p = 0.019, 95% CI = 0.02–0.31. On Alcohol intake and sugar sweetened beverages, participants aged 35–54 years (M = 2.54, SD = 1.29) scored significantly higher than 18–34 years (M = 2.25, SD = 1.25), p = 0.026, 95% CI = 0.03–0.56. See Fig. 2.

Education

There was significant difference in Total score (F = 5.649, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.037), Energy density (F = 6.287, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.041), Portion size (F = 3.152, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.021), Reliable nutrition information source (F = 2.840, p = 0.024, η2 = 0.019) by education level. The Bonferroni correction method showed that on Total score, master’s degree or above (M = 23.77, SD = 5.65) was significantly higher than junior high school or below (M = 16.25, SD = 3.88, p = 0.007, 95% CI = 1.30–13.74), college (M = 20.16, SD = 5.12, p = 0.028, 95% CI = 0.22–7.00), undergraduate (M = 21.93, SD = 6.34, p = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.17–3.51). In terms of Energy density, master’s degree or above (M = 11.15, SD = 2.63) was significantly higher than junior high school or below (M = 7.50, SD = 2.07, p = 0.002, 95% CI = 0.86–6.45), college (M = 9.39, SD = 2.45, p = 0.011, 95% CI = 0.24–3.29), undergraduate (M = 10.29, SD = 2.79, p = 0.012, 95% CI = 0.11–1.61); undergraduate was significantly higher than junior high school or below, p = 0.043, 95% CI = 0.05–5.54. On Reliable nutrition information source, master’s degree or above (M = 1.33, SD = 0.75) was significantly higher than junior high school or below (M = 0.50, SD = 0.54), p = 0.039, 95% CI = 0.02–1.63. See Fig. 3.

Income

Income was significantly different on Portion size (F = 4.378, η2 = 0.022). The Tamhane’s T2 method showed that participants with a per capita monthly household income of >8000RMB (M = 7.77, SD = 2.89) scored significantly higher than participants with <3000RMB (M = 6.46, SD = 2.75, p = 0.041, 95% CI = 0.03–2.57) and 3000–5000RMB (M = 6.91, SD = 2.27, p = 0.014, 95% CI = 0.12–1.60). See Fig. 4.

Residence

Place of residence was significantly different on Total score and Portion size. The independent samples t-test showed that on Total score, participants in cities and towns (M = 22.47, SD = 6.24) scored significantly higher than in countryside (M = 20.30, SD = 5.38), t = 2.922, p = 0.004, 95% CI = 0.710–3.622, d = 0.373. On Portion size, participants in cities and towns (M = 7.58, SD = 2.77) scored significantly higher than in countryside (M = 6.35, SD = 2.45), t = 3.726, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.581–1.876, d = 0.471. See Fig. 5.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a Chinese version of the WMNKQ and to validate its reliability and validity. It is a questionnaire containing 39 items assessing nutrition knowledge in five dimensions related to weight management. Previously, most nutrition knowledge questionnaires focused on declarative knowledge, while WMNKQ and C-WMNKQ added procedural knowledge in addition to declarative knowledge, examining people’s understanding of energy density, food types and portions, and their ability to read food labels. Given the differences in dietary cultures between the East and the West, we have incorporated the Chinese dietary guidelines and dietary patterns into the revision of C-WMNKQ.

The content validity index of the C-WMNKQ is fair, and the face validity reflects the comprehensibility of the questionnaire. Compared with the original English version, the C-WMNKQ made some adjustments as follows: (1) Units of measurement: all ounces were replaced with “grams”, and the beginning of the questionnaire was labeled as “one cup/bowl is about 200 ml, one tablespoon is about 15 ml”. (2) Given that cheese is not popular on the dinner table of Chinese families and that it is difficult for Chinese people to distinguish between “cheddar cheese” and “cottage cheese”, the varieties of cheese in the options were removed and one of them was changed to full-fat yogurt. Given that some respondents claimed that they did not know about “bagels”, they were labeled as such in both words and pictures. (3) In view of the fact that Chinese dishes are mainly fried and stir-fried, and lasagna noodles are rarely made, after consulting with the original author Michael Jensen, “vegetable beef stew → vegetable beef soup → vegetable beef lasagna” was replaced with “stewed potatoes with ribs → potato rib soup → potato fried pork chop”. (4) Based on the Dietary Reference Intake of Nutrients for Chinese Residents (2023) [45], the questionnaire was revised with respect to the energy intake recommended by the United Sates Department of Agriculture (USDA). Although these revisions may have resulted in some deviation from the nutrition knowledge measured by the original questionnaire, cross-cultural adaptation was necessary to adapt to the dietary and cultural habits of our country. In addition, the results of the study showed an increase in the percentage of correct responses for most of the entries after modification.

The overall internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of C-WMNKQ is 0.808, and the overall split-half reliability Guttman coefficient is 0.788, which indicates that the overall internal consistency of the questionnaire is good. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of each dimension of the questionnaire are 0.236–0.649, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of Energy density, Portion size is more than 0.6, which indicates that it is acceptable, but it does not reach 0.7. Theoretically, the reliability coefficient increases with the number of items [46]. Compared to the original questionnaire (Energy density: 19 items, Portion size: 15 items), the C-WMNKQ reduced the number of items for both dimensions (Energy density: 16 items, Portion size: 14 items), which may have led to a decrease in Cronbach’s α coefficient. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for Variety of food affects food intake, Reliable nutrition information source, Alcohol intake and sugar sweetened beverages are less than 0.6, a result similar to the WMNKQ. Due to the small number of items included in these three dimensions, only 2 or 5 questions, it is difficult to fulfill the requirement. The test-retest reliability was measured by both Spearman’s correlation coefficient and ICC value, which is more comprehensive, and the results show that the overall test-retest reliability is good, but some sub-dimensions may not meet the test-retest reliability due to the small number of items.

Nutrition scholars prefer reliability estimates of 0.7 or higher to indicate that the questionnaire is sufficiently reliable for the knowledge and knowledge structure being measured. However, in a comprehensive review, studies measuring nutrition knowledge reported Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.5–0.8 (mainly at 0.6–0.7) [47]. This is similar to the results of our study. In addition, the low internal consistency may also be due to the heterogeneity of populations with different educational backgrounds [43]. The present study included adults with different educational backgrounds, and administering the C-WMNKQ to a larger homogeneous sample (e.g., only college students were included) may improve internal consistency.

Construct validity was measured by comparing the level of nutrition knowledge on weight management between nutrition professionals and finance professionals. Except for Variety of food affects food intake, nutrition professionals scored significantly higher than finance professionals on the total score and the other dimensions, with a total score difference of 26.3%, which is higher than that of the WMNKQ (16% of the overall difference), which verifies that the C-WMNKQ has the ability to differentiate between different levels of nutrition knowledge. Similar to the results of this study, no significant differences were found between the scores of dietitians of WMNKQ and non-nutrition professionals on the dimension Variety of food affects food intake. The possible reasons for this are firstly, this dimension contains only 2 questions, which makes it difficult to reflect the difference in knowledge level between the two; secondly, the previous expert consultation and pre-survey in our study also showed that both nutrition professionals and non-nutrition professionals have some bias towards this concept. This may be due to confusion with the Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents 2022 [44], which recommends “a variety of foods, reasonable combinations, requiring an average daily intake of more than 12 types of foods”. This dietary guideline is to ensure that people are well nourished, whereas this questionnaire examines weight management, and providing fewer food items helps to reduce food intake and thus achieve weight control.

In terms of criterion validity, several previous studies have assessed the criterion validity of the questionnaire and the dimensions mainly by comparing the changes in outcomes before and after the nutrition knowledge intervention course [16, 33]. Considering the complexity of the intervention course design and the difficulty of controlling confounding factors, this study measured the criterion validity by correlating the questionnaire with the C-GNKQ. The results showed that the total score of the C-WMNKQ was significantly and positively correlated with the total score of the C-GNKQ and the scores of each dimension, which had good criterion validity.

In terms of convergent validity, the results of this study were generally similar to expectations: women’s nutrition knowledge was higher than men’s, the higher the level of education the higher the level of nutrition knowledge, participants with a per capita monthly household income of >8000RMB scored significantly higher on partial nutrition knowledge than those <3000RMB and 3000–5000RMB, and participants who lived in cities and towns had higher nutrition knowledge than those in countryside. However, it is not consistent with expectation in terms of age, the partial nutrition knowledge scores of participants aged 35–54 years in this study were significantly higher than those aged 18–34 years, probably due to the fact that middle-aged people have more life experience and thus have higher nutrition knowledge levels. Previous studies have also pointed out that middle-aged and older adults have higher nutrition knowledge scores than younger adults [48], and that the level of nutrition knowledge increases with age [49]. In addition, the Bonferroni correction method was used in this study to tightly control p values for multiple category comparisons, which may have resulted in some results being affected by the Bonferroni adjustment and losing significance.

C-WMNKQ has a broad application prospect. It can be used as a tool to guide public nutrition education to improve the content of nutrition education and promote Chinese understanding of weight management and nutrition knowledge. It can be used to measure nutrition knowledge to assess the effectiveness of nutrition education interventions. It facilitates nutritional counseling for physicians to find the gaps in patients’ nutrition knowledge and develop targeted nutritional treatment plans. In conclusion, the C-WMNKQ will serve as a useful tool to improve the effectiveness of weight management in the Chinese population.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this study as follows: the big limitation of the knowledge assessments in our questionnaire is that answers are unequivocally correct, and that the correctness of the statements remains static over time. The lack of an “uncertain” option in the questionnaire options may result in participants guessing the answer. Most of the participants in this study were willing to participate in the survey, and they may have more concerns and interests about their weight and healthy eating, which may have led to selection bias. The limitations of convenience sampling made the sample less representative, with a smaller percentage of males, middle-aged and older groups, less educated, and rural populations. No nutrition intervention was used to measure criterion validity and no valid evidence was obtained on whether the C-WMNKQ could improve nutrition knowledge scores after the intervention. In the future, the C-WMNKQ can be used in regional and large-scale nutrition knowledge censuses to reduce selection bias and improve sample representativeness. The C-WMNKQ can be used as a nutrition education tool to design relevant nutrition education methods to compare changes in nutrition knowledge scores before and after intervention.

Conclusions

The C-WMNKQ is the first instrument to measure nutrition knowledge related to weight management among Chinese adults, and it has been validated for scientific and comprehensive reliability and validity, with good overall reliability and validity. The C-WMNKQ is able to reflect information on the level of nutrition knowledge of Chinese, contributes to the understanding of the nutrition knowledge domain related to weight management, and may play a role in predicting long-term weight loss success. However, further modifications are needed to address the low reliability of some of the dimension items and to better adapt the questionnaire to Chinese eating habits and patterns.

Data availability

All of the individual participant data collected during the research, after de-identification, will be provided by the authors without unnecessary reservations.

References

National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. WS/T 428-2013 adult weight determination. 2013. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ewebeditor/uploadfile/2013/08/20130808135715967.pdf.

Liu N. Study on the behavioral intention of weight management in adults (20-59 years) in Shanxi Province and its influence mechanism. Shanxi_ Shanxi Normal University, 2020.

Jepsen MM, Christensen MB. Emerging glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2021;26:231–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728214.2021.1947240.

Spronk I, Kullen C, Burdon C, O’Connor H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1713–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514000087.

Scalvedi ML, Gennaro L, Saba A, Rossi L. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake: an assessment among a sample of Italian adults. Front Nutr. 2021;8:714493. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.714493.

Żarnowski A, Jankowski M, Gujski M. Nutrition knowledge, dietary habits, and food labels use—a representative cross-sectional survey among adults in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:11364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811364.

Brown R, Seabrook JA, Stranges S, Clark AF, Haines J, O’Connor C, et al. Examining the correlates of adolescent food and nutrition knowledge. Nutrients. 2021;13:2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13062044.

Bany-Yasin H, Elmor AA, Ebrahim BK, Ahmed AAM, Alarachi MR, Abedalqader L, et al. Exploration of the nutrition knowledge among general population: multi-national study in Arab countries. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:1178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15791-9.

Fu Y, Ma Y, Jiang S, Kuang X. Analysis on the awareness of nutrition healthy knowledge among residents aged 18-64 in Hainan Province in 2021. J Prev Med Inf. 2023;39:520–5.

Qu M, Song Q, Shi Z, Shen L, Mai S, Lu W, et al. Survey on the awareness rate of nutrition and health knowledge among residents aged 18-64 in Shanghai in 2021. J Hyg Res. 2023;52:534–40.

Ma M, Liu M, Liu M, Yang Y, Liu Z, Yan L. Analysis on the awareness and influencing factors of nutritional health knowledge among residents aged 18-64 years in Sichuan Province in 2021. J Prev Med Inf. 2022;38:1588–91.

Huang Y, Pan Y, Liu Y, He L, Wu S. Survey on nutritional health knowledge of residents of Guizhou province in 2021. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;17:611–13.

World Health Organization. United Nations Action on Nutrition (2016–2025). 2024. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB152/B152_24-ch.pdf.

Xinhua News Agency. CPC Central Committee and State Council Issues Outline of “Healthy China 2030” Plan. 2016. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm.

Healthy China Action Promotion Committee. Healthy China Action (2019-2030). 2019. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm.

Mikhail D, Rolls B, Yost K, Balls-Berry J, Gall M, Blixt K, et al. Development and validation testing of a weight management nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Int J Obes. 2020;44:579–89. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0510-1.

Parmenter K, Wardle J. Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:298–308. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600726.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Choosing foods for your family. 2013. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/eat-right/choosing-foods.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy eating for a healthy weight. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/healthy_eating/index.html.

United States Department of Agriculture. Choose MyPlate. 2018. https://www.choosemyplate.gov/.

Matsumoto M, Tanaka R, Ikemoto S. Validity and reliability of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for Japanese adults. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2017;63:298–305. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.63.298.

Guo J, Li Z. The introduction process of scale and its evaluation standards. Chin J Nurs. 2012;47:283–5.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

Shi J, Mo X, Sun Z. Content validity index in scale development. J Cent South Univ Med Sci. 2012;37:152–5.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Kline P. The handbook of psychological testing. London; New York: Routledge; 1993.

Gao Z, Wu F, Lv G, Zhuang X, Ma G. Development and validity of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire (GNKQ) for Chinese adults. Nutrients. 2021;13:4353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124353.

Haladyna TM. Developing and validating multiple-choice test items. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge; 2004.

Van Tiggelen H, Alves P, Ayello E, Bååth C, Baranoski S, Campbell K, et al. Development and psychometric property testing of a skin tear knowledge assessment instrument (OASES) in 37 countries. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:1609–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14713.

Öztürk Birge A, Tel Aydın H, Salman F. The development of a delirium knowledge test for intensive care nurses: a validity and reliability study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;61:102900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102900.

Cho E. Making reliability reliable: a systematic approach to reliability coefficients. Organ Res Methods. 2016;19:651–82.

Bhawra J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hall MG, Vanderlee L, White CM, Hammond D. Patterns and correlates of nutrition knowledge across five countries in the 2018 international food policy study. Nutr J. 2023;22:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-023-00844-x.

Kliemann N, Wardle J, Johnson F, Croker H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1174–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.87.

Hou L, Xia X, Du Y, Zhang Y, Li S, Liu W, et al. Nutritional knowledge, attitudes, and practices among residents in the Northeast areas of China during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1296869. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1296869.

Fu L, Shi Y, Li S, Jiang K, Zhang L, Wen Y, et al. Healthy diet-related knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) and related socio-demographic characteristics among middle-aged and older adults: a cross-sectional survey in Southwest China. Nutrients. 2024;16:869. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16060869.

Yang Y, He D, Wei L, Wang S, Chen L, Luo M, et al. Association between diet-related knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and self-rated health in Chinese adult residents: a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:720. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08896-y.

Axelson ML, Brinberg D. The measurement and conceptualization of nutrition knowledge. J Nutr Educ. 1992;24:239–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(12)81238-6.

Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

Hendrie GA, Cox DN, Coveney J. Validation of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in an Australian Community Sample. Nutr Diet. 2008;65:72–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0080.2007.00218.x.

Alsaffar AA. Validation of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in a Turkish Student Sample. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:2074–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011003594.

Jones AM, Lamp C, Neelon M, Nicholson Y, Schneider C, Wooten Swanson P, et al. Reliability and validity of Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.003.

Bukenya R, Ahmed A, Andrade JM, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Muyonga J, Andrade JE. Validity and reliability of General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for adults in Uganda. Nutrients. 2017;9:172. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020172.

Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary guidelines for Chinese residents: 2022. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2022.

Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary reference intake of nutrients for Chinese residents (2023). Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2023.

Ferguson GA, Takane Y. Statistical analysis in psychology and education: international edition. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Co; 1989.

Contento I. Review of nutrition education research in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 1998 to 2007. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40:331–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.001.

Putnoky S, Banu AM, Moleriu LC, Putnoky S, Șerban DM, Niculescu MD, et al. Reliability and validity of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for adults in a Romanian population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:1576–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0616-5.

Gruber M, Iwuchukwu CG, Sperr E, König J. What do people know about food, nutrition and health?—General Nutrition Knowledge in the Austrian population. Nutrients. 2022;14:4729. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14224729.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Jensen for his helpful guidance during the questionnaire revision process and for his support of this study. We are grateful to the cooperation of the volunteers who participated.

Funding

This study was funded by the Medical and Health Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province (2023KY794).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and JQ: conceptualization. JS, JQ and KH: methodology, validation. JF, FC, MZ, WX and SZ: formal analysis, investigation. MW and JQ: resources. JS: writing—original draft. JQ: writing—review & editing. JS and FC: visualization. JQ and KH: supervision. MZ, WX and SZ: project administration. MW: funding acquisition. All authors reviewed and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript, and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, J., Fang, J., Huang, KR. et al. Development and validation testing of a weight management nutrition knowledge questionnaire for Chinese adults (C-WMNKQ). Int J Obes 49, 1092–1103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01750-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01750-4