Abstract

Objective

This study determined factors associated with persistent bloodstream infections (BSIs) for infants in the NICU to identify when follow up blood cultures (FUBCs) have increased utility.

Study design

Single center study of all infants in a level IV NICU (n = 121) with a positive blood culture over a five-year period. Clinical and microbiological variables were examined with bivariate and multi-regression analyses to identify factors associated with persistent BSI, defined as growth of the same organism >48 h after the index culture.

Results

The recovery of Staphylococcus aureus (OR = 6.10, p < 0.001), male sex (OR = 3.31, p = 0.020), the presence of a central venous catheter (OR = 3.73, p = 0.020), and BSI in the setting of late-onset sepsis (p < 0.001) were associated with persistent BSI. No infants with either early-onset sepsis or growth of Streptococcal sp. had a persistent BSI.

Conclusion

In the NICU, both patient and microbial characteristics can inform diagnostic stewardship regarding the need for FUBCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) in premature infants are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in this high-risk population [1, 2]. In premature infants with clinical signs of infection, the evaluation often entails obtaining two separate site blood cultures, with a minimum of 1.0 ml of blood per bottle, although guidance can vary among different references [3,4,5,6]. Drawing blood from premature infants is challenging given the size and caliber of their vessels [7]. Multiple attempts at collecting blood for culture can lead to contamination and increased antibiotic use [8]. Unnecessary blood collection should also be avoided due to infants’ lower circulating blood volume compared with older children and adults [9]. One aspect of diagnostic stewardship is the practice of avoiding tests when the pre-test probability of a clinically actionable result is low. Although the approach can vary, criteria exist for when to draw blood cultures for infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) as part of a sepsis evaluation, [3, 10]. After an initial negative blood culture, the clinical utility of frequent follow-up blood cultures (FUBCs) is low [11]. However, there is less information for infants in the NICU about when to draw FUBCs after an index positive result.

In the adult population, indications for FUBCs after a positive blood culture include an endovascular focus, the presence of a central venous catheter (CVC) or the recovery of Staphylococcus aureus or yeast [12,13,14]. FUBCs are generally not recommended for BSI attributed to gram-negative rods (GNR) or Streptococcal species [12, 15, 16]. In hospitalized children outside of the NICU, studies vary regarding the need for FUBCs after GNR bacteremia [17,18,19]. Similar to adults, we recently showed no positive FUBCs from children that initially grew any Streptococcal species including S. agalactiae (Group B streptococcus, GBS) as well as a higher likelihood of persistent bacteremia in the setting of S. aureus, yeast, the presence of a CVC, and a history of a previous BSI [18]. At our institution, FUBCs are common for any child after a positive blood culture result regardless of the organism or clinical suspicion of BSI. Given the lack of data on FUBCs after an index positive for infants in the NICU, we examined the risk factors for persistent BSI to inform clinical decisions regarding the need for FUBC.

Methods

Setting and patient population

We conducted a single center cohort study from August 1, 2016- December 31, 2021, at the Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital (YNHCH) Level IV NICU, a tertiary referral center supporting a high-risk delivery network. From 1992–2017, the 54-bed YNHCH NICU had an open bay design with multiple infants sharing a large space. In January 2018, the NICU moved to a new location incorporating 68 beds comprised mostly of single rooms. Most NICU admissions are inborn with approximately 15% transferred in from regional community hospitals after delivery. Once infants are discharged from the NICU, subsequent readmissions are to a pediatric unit. During the study period, weekly screening was performed for methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) colonization with colonized infants placed on contact precautions.

Initial inclusion criteria for this investigation included any infant admitted to the YNHCH NICU from August 1, 2016- December 31, 2021, with a positive blood culture. Both yeast and bacteria were included to understand rates of persistence for each type of organism. While positive blood cultures with yeast are rare in our unit, when recovered it is an indication for FUBCs [13]. Persistent BSI was defined as a FUBC that was positive for the same organism >48 h after the time of the initial blood culture collection. Infants were excluded if they died prior to 48 h after the initial positive culture and a FUBC could not be obtained. A new positive blood culture obtained greater than seven days after the initial positive or recovery of a different organism from the FUBC was considered a new event. This protocol was approved by the Yale Investigations Review Board with a waiver of informed consent (#2000032485).

Blood culture collection and clinical microbiology

Blood cultures were collected via sterile technique, using povidone iodine as an antiseptic for skin disinfection prior to arterial stick or venipuncture. For blood cultures from CVCs, the hub was wiped with either 70% isopropyl alcohol or a 3.15% chlorhexidine gluconate/70% isopropyl alcohol product per the manufacturer’s instruction for use. Blood culture guidelines at our institution state that unless anaerobic infection is strongly suspected, blood should be drawn from two separate sites and inoculated into two aerobic adult blood culture bottles. Cultures for late-onset sepsis (LOS) were typically obtained from two separate peripheral venipunctures or arterial punctures. For early-onset sepsis (EOS), if umbilical lines were placed, a culture was obtained at sterile line insertion from each line [8]. If only a single line was placed, a second peripheral culture was attempted. If no lines were placed, two peripheral cultures were attempted. This practice was followed consistently during the study period. Our laboratory does not use pediatric bottles. Our institution follows the recommendations from the 2018 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, recommending that at least one ml of blood be obtained per blood culture bottle to reliably detect bacteremia [3]. Blood culture volumes were not routinely monitored for this unit during the study period.

Details on the work up of positive blood cultures by the clinical microbiology laboratory during this period have been previously published [18]. Briefly, the on-site clinical microbiology laboratory uses the BD BacTec blood culture system (Becton, Dickinson Life Sciences) with positive results subject to Gram stain followed by the inoculation of appropriate agar plates. In 2017 the MRSA/SA Blood Culture Assay (Cepheid, USA) was introduced for positive blood cultures demonstrating gram-positive cocci in clusters. Identification of organisms after growth was primarily performed by matrix assisted laser-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Vitek MS, Biomerieux) supplemented with antigen or biochemical methods for Staphylococcal species or those failing MALDI-TOF MS identification. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed per the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines at the time of the culture and included microbroth dilution (Vitek 2, Biomerieux), disk diffusion, or E-test depending on the organism and antibiotic combination. Yeast recovered from standard blood culture bottles were worked up in a similar manner and identified by MALDI-TOF. Fungal blood cultures were not routinely performed during the study period.

Data collection

Yale New Haven Hospital has tracked all positive blood cultures in the newborn population since 1928 [20]. Positive blood cultures were categorized by timing, EOS, defined as an organism detected at \(\le\)3 days of life, and LOS as one detected at >3 days. Evaluation and treatment for suspected EOS was based largely on the presence of maternal risk factors (e.g., chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of amniotic membranes) and for LOS on clinical signs of infection including apnea, bradycardia, temperature instability, glucose instability, lethargy, and hypotension requiring intervention. Data from August 1, 2016- December 31, 2021, were cross checked with information extracted from the electronic medical record by the Yale Data Analytics Team using the inclusion criteria above. Manual chart review confirmed demographic and clinical variables, determined whether empiric antibiotics would be effective based on susceptibility testing, whether the recovered organism was a likely pathogen or contaminant and the timing of CVC removal in relation to the index positive blood culture. A patient was considered to have a CVC if one was present within 24 h of the index blood culture. Empiric antibiotics were given to all infants in the cohort at the time of the index blood culture. The antibiotics were considered effective if either the organism is universally considered susceptible to an antibiotic (e.g., vancomycin for S. aureus, ampicillin for GBS) or chart review confirmed the organism was susceptible to any empiric antibiotic started at the time of index culture. The antibiotic regimens used during the study period were ampicillin and gentamicin for EOS and vancomycin and gentamicin for LOS. Expanded coverage typically with a third generation cephalosporin was considered in the following situations: (1) High clinical suspicion for a gram-negative infection (e.g. infant delivered to mom with a current or recent gram-negative infection), (2) Evidence of meningitis (e.g. clinical signs or concerning cerebrospinal fluid indices), (3) significant clinical deterioration consistent with overwhelming sepsis or (4) known colonization or a past maternal or infant infection with an organism not covered by the standard empiric regimen.

Criteria for a likely contaminant were defined as a single positive blood culture not treated for ≥5 days that yielded either an organism not commonly associated with neonatal sepsis, or the culture was polymicrobial. Likely contaminants were included in the initial analyses to assess the results of FUBCs for these isolates. Aggregate, deidentified data are available by contacting the corresponding author.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics are presented at the patient and specimen level and include frequencies with percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile range for quantitative variables. To test for demographic and clinical factors associated with persistent BSI, generalized estimating equations with a binomial distribution and logit link was run separately for each factor. Both leukopenia and thrombocytopenia have been identified as risk factors for severe neonatal sepsis [21, 22]. Peripheral white blood cell and platelet counts were included if they were collected within 24 h of the index blood culture. The model included unstructured covariance with robust standard errors. This was followed with a backward stepwise multivariate model using the variables in Tables 1 and 2 to determine the combination of factors that predicted persistent BSI. These variables were initially selected based on the possible association with persistent BSI or severe sepsis and included in the multivariate model based on results from the bivariate model [12, 18]. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the multivariate model removing likely contaminants. There was no alpha adjustment for multiple testing. Factors with p-values < 0.05, as determined by bootstrap sampling, were retained in the final multivariate model.

Results

Patient demographics

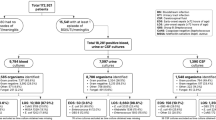

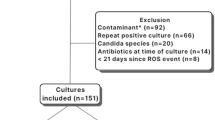

One hundred and forty infants had a positive blood culture during the study period with 19 meeting exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The 121 remaining infants had 138 positive index blood cultures (Fig. 1). In our study cohort, 99% (136/138) of specimens were followed with a second blood culture. Two positive index cultures did not have FUBCs, one was polymicrobial and treated with antibiotics and the other grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) and was considered a contaminant. Seventeen percent (24/138) of positive index cultures were persistently positive on FUBC with the same organism (Fig. 1). Six FUBCs grew a new index organism, all CoNS, that was not present in the previous index blood culture. Further FUBCs were negative in all six episodes. Four infants grew the same organism (three enteric GNRs and CoNS) on a later blood culture as a new event. The time between the two blood cultures for the enteric GNRs ranged from 39–124 days and we did not determine whether they were identical isolates. One patient grew CoNS 124 days after an initial culture and again eight days later. Index cultures that grew likely contaminants represented 15% (20/138) of the specimens. Ninety five percent (19/20) of infants with a likely contaminant were subject to a FUBC, all of which were negative. Fifteen index positive blood cultures, 10 for LOS and five for EOS, were drawn from CVCs, including seven umbilical catheters. The two infants without FUBCs were not considered persistent BSI.

The demographics of the patient population are shown in Table 1. The median gestational age was 29 weeks [IQR 25–37]; 26 weeks for infants with persistent BSI compared with 30 weeks for those with a single positive blood culture. The median white blood cell count for the entire cohort was 12,900/ml [IQR 7800/ml -21,300/ml]; 14,300/ml in infants with persistent BSI compared with 12,100/ml in infants without persistent BSI. The median platelet count for the entire study group was 219,000/ml [IQR 106,000/ml -300,000/ ml]; 131,000/ml for infants with persistent BSI and 230,000/ml for those without. All positive FUBCs occurred in infants being evaluated and treated for LOS. The median and average days of life of the index blood culture for infants with persistent BSI and LOS were 10.5 days and 18.5 days (6–91 days) respectively. No infant younger than six days of life had a persistent BSI.

Microbiology

For 19 infants, persistent BSI could not be determined because of death within 48 h of the index culture; these infants were excluded from further analysis. These positive blood cultures grew a variety of gram-negative and gram-positive organisms (Table 1). The recovered microbes from initial cultures from eligible patients are shown in Table 2. Consistent with literature from adults and older children, the most common organism associated with persistent BSI was S. aureus, which accounted for 63% (15/24) of all persistent BSI. In fact, 41% (15/37) of S. aureus BSIs remained positive at 48 h, despite effective empiric antibiotics for 93% (14/15) of these infants (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). There were four infants with MRSA positive blood cultures, all treated with empiric vancomycin. Fifty percent (2/4) of MRSA were persistent. We were interested in whether early CVC removal prior to 48 h after the index culture reduced S. aureus persistence. Of the 20 infants with a CVC and S. aureus, the CVC was removed in 33% (4/12) of infants with persistent S. aureus and in 25% (2/8) of infants who cleared S. aureus prior to 48 h. For all remaining infants with a CVC, only one was removed within 48 h of the index culture. The index culture grew CoNS that was persistent despite CVC removal.

Positive blood cultures growing enteric GNRs were recovered in 12% (5/46) of FUBC (Table 2). Klebsiella sp. caused persistent BSI in 20% (2/10) of infants while Escherichia coli was recovered in 8% (2/26) of FUBCs (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). Of the 15 positive blood cultures drawn directly from a CVC, one was persistent, growing Enterococcus faecalis. No Streptococcal species (n = 18) were recovered in any FUBC (Table 2). Of the organisms without available antibiotic susceptibility data or treated empirically with ineffective antibiotics, of which 14 were considered likely contaminants, the only persistent organism (1/27, 4%) was a single S. aureus. Twenty three of the 24 persistent organisms (96%) were empirically started on an antibiotic that the organism was susceptible to, demonstrating persistence regardless of effective therapy (Supplementary Table 2). During the study period only two blood cultures were positive for yeast, both Candida parapsilosis. One of these was persistent.

Of the 103 blood cultures drawn as part of an evaluation for LOS, S. aureus (36/103, 35%), enteric GNRs (26/103, 25.2%), and CoNS (22/103, 21.3%) were recovered most frequently (Supplementary Table 3). For the 42 EOS evaluations, enteric GNRs (16/42, 38%) were most commonly isolated followed by CoNS (7/42, 16.7%) and Viridans group Streptococci (5/42, 11.9%). The percentage of likely contaminants was higher for EOS cultures (17/42 41%) including 83% (6/7) of CoNS and 4/5 (80%) Viridans group Streptococci. Meanwhile blood cultures collected during a LOS evaluation had lower numbers of likely contaminants (5/103, 4.8%), all CoNS (Supplementary Table 3).

Host and microbial factors associated with persistent BSI

Bivariate analyses revealed that the following factors were significantly associated with persistence: male sex, LOS ( > 3 days after birth; as compared with EOS), presence of CVC within 24 h of collection of the index blood culture, any type of respiratory support, post-natal steroid exposure within 48 h of the index culture, and recovery of S. aureus from the index culture (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4).

Premature babies are more likely to require a CVC and respiratory support and receive steroids. To account for these potential confounding variables related to prematurity, a multivariate model was constructed. In this model, factors that remained significantly associated with persistent BSI included LOS, recovery of S. aureus, presence of a CVC, and male sex (Table 3). We included blood cultures with likely contaminants because we were interested in how many received FUBC and whether new organisms were isolated. However, the inclusion of probable contaminants, with an increased proportion of CoNS, could impact the analysis of factors associated with persistent BSI. Therefore, we performed sensitivity analysis removing the likely contaminants and there were no changes to the results of the multivariable model (data not shown). Given the higher rates of persistence in smaller babies, we also re-analyzed the data comparing all infants above and below 1500 grams birth weight and this also did not change the results of the model.

Discussion

Collecting blood from premature infants is challenging. Informed diagnostic stewardship that safely reduces the number of blood draws in the NICU population is possible and can reduce patient harm [20]. While there are clear indications in the adult population regarding FUBCs after an index positive culture, data to help guide this decision for infants in the NICU are lacking. In this cohort, 99% of infants with an initial positive blood culture had a FUBC, including 95% of likely contaminants. This suggests an opportunity to safely reduce the number of FUBCs and associated needle sticks. Like literature for adults and older children, the recovery of S. aureus and the presence of a CVC were both associated with a higher rate of persistence [12, 18]. Infants with either of these risk factors require a FUBC to document clearance and help determine length of antibiotic therapy. Given the prevalence of S. aureus invasive infections in NICUs, there is a need for continued efforts to understand the epidemiology and reduce invasive disease for both MSSA and MRSA in the NICU setting [23,24,25]. Consistent with previous studies of adults and children outside of the NICU, no Streptococci of any species were recovered from FUBCs obtained after 48 h. [15, 18]. If confirmed with larger data sets, this may offer an opportunity for diagnostic stewardship by reducing FUBCs in infants with Streptococcal bacteremia. There may also be an opportunity for antimicrobial stewardship as well. Currently in our NICU, for most positive blood cultures with a likely pathogen, the practice is to consider day one of treatment the first day with a negative FUBC. An alternative strategy for infants who are clinically improving with Streptococcal would be to select treatment length based on published guidelines, without the need for a negative FUBC. We are currently evaluating our practice of routine FUBC on infants with positive Streptococcal blood cultures.

LOS was determined to be a significant predictor of persistent bacteremia as compared with EOS and, surprisingly, no infant with EOS (n = 39 specimens) had a persistent BSI. In the NICU population, the decision to evaluate and initiate empiric treatment for EOS is largely based on risk factor assessment, including gestational age and the presence of maternal risk factors for neonatal infection [3, 26]. In neonates <35 weeks’ gestation, given their increased risk of infection and associated morbidity and mortality, assessment and intervention occurs quickly after birth and often in the absence of clear clinical signs of infection. Alternatively, the decision to evaluate and treat for LOS is based almost exclusively on a change in baseline condition and the presence of clinical and/or laboratory signs of infection. A prior study on the use of polymerase chain reaction as part of the evaluation for suspected neonatal infection determined a positive correlation between higher bacterial loads in the blood and the presence of a higher number of clinical signs of infection [27]. It has also been speculated that intrapartum antibiotic exposure may lead to lower bacterial levels in neonates with EOS [28]. In our study population with confirmed EOS, only 17% had clinical signs of infection at the time of the evaluation (as compared with 100% of those with LOS), and 71% of infants evaluated for EOS were delivered in the setting of intrapartum antibiotics administration (data not shown). It is therefore possible that higher bacterial loads in infants with LOS as compared with infants with EOS contributed to the significantly higher observed odds of persistent BSI. Despite our findings that no EOS episode was associated with persistent BSI, we continue to recommend FUBC for all gram-negative sepsis, including EOS, given the serious nature of this infection and the small sample size in this cohort.

The pathophysiology of LOS is distinct from EOS and may also contribute to persistent BSI. Unlike EOS, which originates from ascension of maternal genitourinary tract microbes during labor or rupture of membranes, LOS is usually a hospital-acquired infection from exposure to invasive procedures or other environmental sources [29,30,31]. Pathogen exposure in LOS can occur due to contamination of indwelling medical devices, such as a CVC or an endotracheal tube. This contrasts with EOS, where pathogen exposure typically originates during labor and delivery and exposure removed once the infant is delivered [29].

A near equal percentage of male and female infants in our study population had an initial positive blood culture, yet male sex was associated with significantly higher odds of a positive FUBC. This finding aligns with observed gender disparities in the preterm population, where several studies have demonstrated higher rates of morbidity and mortality among male preterm infants compared with their female counterparts [27, 32, 33]. Of the 19 infants that died within 48 h of a positive index culture, 13 (68%) were male (Supplementary Table 1). A 2022 study investigated the association between sex and long-term pediatric infectious disease morbidity in a cohort of 2111 dichorionic twin pairs followed up to 18 years of age. A higher risk of ear, nose, throat, central nervous system, and respiratory infections were observed in male twins as well as a higher cumulative hazard of infectious disease-related morbidity and hospitalization as compared with females [34]. Although the precise mechanism of these differences remains unknown, gender-specific immunologic, genetic, and hormonal differences have been hypothesized to contribute [33]. To our knowledge, an association between male sex and persistent BSI has not been previously observed.

There are limitations that require additional study. As a single center study, the number of persistent BSIs were low. There were very few Candida sp. BSIs. Yeast are an important pathogen for the neonatal population, and FUBCs are required to determine treatment length [13]. Our laboratory only stocks adult standard blood culture bottles. There is conflicting evidence as to the improved detection of pathogenic organisms comparing pediatric and standard blood culture bottles [35]. While pediatric bottles are not formally recommended for children, for small blood volumes they may provide enhanced sensitivity and we cannot exclude the possibility of false negative blood cultures within our cohort [6, 35, 36]. We also did not measure blood volume received for culture during the study period. Thus, it is possible there were missed episodes of persistent BSI if the FUBC did not have sufficient volume to detect growth. We did not use anaerobic blood cultures in this cohort. Anaerobic bottles have been found to enhance detection of certain pathogens, especially in EOS [37]. As a result, we cannot comment on the rate of persistent BSI for strict anaerobes or other pathogens when grown under anaerobic conditions. We also do not have data as to whether one or two blood culture bottles were positive and could not include this as a variable to predict persistent BSI.

Conclusions

In this single center study, S. aureus bacteremia, the presence of a CVC, male sex and LOS were associated with persistent BSI in infants in the NICU, suggesting clinical utility of documenting clearance with FUBCs. For EOS and Streptococcal bacteremia, no persistent BSIs were identified and, if validated in larger studies at other centers and in more recent cohorts, offer an opportunity for diagnostic stewardship.

Data availability

The data set, after removal of identifying information, is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Stoll BJ, Puopolo KM, Hansen NI, Sanchez PJ, Bell EF, Carlo WA, et al. Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis 2015 to 2017, the Rise of Escherichia coli, and the Need for Novel Prevention Strategies. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:e200593.

Flannery DD, Edwards EM, Coggins SA, Horbar JD, Puopolo KM. Late-onset sepsis among very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2022058813

Puopolo KM, Benitz WE, Zaoutis TE, Committee On Fetus and Newborn, Committee On Infectious Diseases. Management of Neonates Born at >/=35 0/7 Weeks’ gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20182894.

Huber S, Hetzer B, Crazzolara R, Orth-Holler D. The correct blood volume for paediatric blood cultures: a conundrum?. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:168–73.

Woodford EC, Dhudasia MB, Puopolo KM, Skerritt LA, Bhavsar M, DeLuca J, et al. Neonatal blood culture inoculant volume: feasibility and challenges. Pediatr Res. 2021;90:1086–92.

Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, Carroll KC, Chapin KC, Gonzalez MD, et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 2024:ciae104. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae104.

Legemaat M, Carr PJ, van Rens RM, van Dijk M, Poslawsky IE, van den Hoogen A. Peripheral intravenous cannulation: complication rates in the neonatal population: a multicenter observational study. J Vasc Access. 2016;17:360–5.

Fleiss N, Shabanova V, Murray TS, Gallagher PG, Bizzarro MJ. The diagnostic utility of obtaining two blood cultures for the diagnosis of early onset sepsis in neonates. J Perinatol. 2024;44:745–7.

Widness JA, Madan A, Grindeanu LA, Zimmerman MB, Wong DK, Stevenson DK. Reduction in red blood cell transfusions among preterm infants: results of a randomized trial with an in-line blood gas and chemistry monitor. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1299–306.

Verstraete EH, Mahieu L, d’Haese J, De Coen K, Boelens J, Vogelaers D, et al. Blood culture indications in critically ill neonates: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:1565–72.

Verstraete EH, Mahieu L, Haese JD, De Coen K, Boelens J, Vogelaers D, et al. Clinical utility of repeated blood culture sampling in critically ILL neonates. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. 2015;3.

Wiggers JB, Xiong W, Daneman N. Sending repeat cultures: is there a role in the management of bacteremic episodes? (SCRIBE study). BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:286.

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–50.

Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18–55.

Siegrist EA, Wungwattana M, Azis L, Stogsdill P, Craig WY, Rokas KE. Limited Clinical Utility of Follow-up Blood Cultures in Patients With Streptococcal Bacteremia: An Opportunity for Blood Culture Stewardship. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa541.

Canzoneri CN, Akhavan BJ, Tosur Z, Andrade PEA, Aisenberg GM. Follow-up Blood Cultures in Gram-Negative Bacteremia: Are They Needed?. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1776–9.

Uehara E, Shoji K, Mikami M, Ishiguro A, Miyairi I. Utility of follow-up blood cultures for Gram-negative rod bacteremia in children. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25:738–41.

Puthawala CM, Feinn RS, Rivera-Vinas J, Lee H, Murray TS, Peaper DR. Persistent bloodstream infection in children: examining the role for repeat blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2024;62:e0099824.

Franz-O’Neal E, Olson J, Thorell EA, Cipriano FA. Follow-Up blood cultures in young infants with bacteremic urinary tract infections. Hosp Pediatr. 2021:hpeds.2021-006012. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2021-006012.

Bizzarro MJ, Shabanova V, Baltimore RS, Dembry LM, Ehrenkranz RA, Gallagher PG. Neonatal sepsis 2004-2013: the rise and fall of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1193–9.

Arabdin M, Khan A, Zia S, Khan S, Khan GS, Shahid M. Frequency and Severity of Thrombocytopenia in Neonatal Sepsis. Cureus. 2022;14:e22665.

Sahu P, Srinivasan M, Thunga G, Lewis LE, Kunhikatta V. Identification of potential risk factors for the poor prognosis of neonatal sepsis. Med Pharm Rep. 2022;95:282–9.

Popoola VO, Colantuoni E, Suwantarat N, Pierce R, Carroll KC, Aucott SW, et al. Active surveillance cultures and decolonization to reduce staphylococcus aureus infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:381–7.

Annavajhala MK, Kelly NE, Geng W, Ferguson SA, Giddins MJ, Grohs EC, et al. Genomic and Epidemiological Features of Two Dominant Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Clones from a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Surveillance Effort. mSphere. 2022;7:e0040922.

Barrett RE, Fleiss N, Hansen C, Campbell MM, Rychalsky M, Murdzek C, et al. Reducing MRSA Infection in a New NICU During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2023;151:e2022057033.

Puopolo KM, Benitz WE, Zaoutis TE, Committee on fetus and newborn, committee on infectious diseases. Management of neonates born at </=34 6/7 Weeks’ gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20182896.

Oeser C, Pond M, Butcher P, Bedford Russell A, Henneke P, Laing K, et al. PCR for the detection of pathogens in neonatal early onset sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0226817.

Higgins RD, Saade G, Polin RA, Grobman WA, Buhimschi IA, Watterberg K, et al. Evaluation and management of women and newborns with a maternal diagnosis of chorioamnionitis: summary of a workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:426–36.

Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–7.

Fleiss N, Schwabenbauer K, Randis TM, Polin RA. What’s new in the management of neonatal early-onset sepsis?. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023;108:10–4.

Coggins SA, Glaser K. Updates in Late-Onset Sepsis: Risk Assessment, Therapy, and Outcomes. Neoreviews. 2022;23:738–55.

Bacak SJ, Baptiste-Roberts K, Amon E, Ireland B, Leet T. Risk factors for neonatal mortality among extremely-low-birth-weight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:862–7.

O’Driscoll DN, McGovern M, Greene CM, Molloy EJ. Gender disparities in preterm neonatal outcomes. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107:1494–9.

Leybovitz-Haleluya N, Sheiner E, Pariente G, Wainstock T. The association between fetal gender in twin pregnancies and the risk of pediatric infectious diseases of the offspring: A population-based cohort study with long-term follow up. J Perinatol. 2022;42:1587–91.

Dien Bard J, McElvania TeKippe E. Diagnosis of Bloodstream Infections in Children. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1418–24.

CLSI. Principles and Procedures for Blood Cultures 2nd ed. CLSI guideline M47. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2022.

Gottschalk A, Coggins S, Dhudasia MB, Flannery DD, Healy T, Puopolo KM, et al. Utility of Anaerobic Blood Cultures in Neonatal Sepsis Evaluation. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2024;13:406–12.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Stephen Uss from the Yale Data Analytics team for assistance with data extraction.

Funding

Dr. Lee was funded in part by training grant T32AI00721 from the NIAID/NIH. No other authors received external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Thomas S. Murray, Dr. Noa Fleiss, Dr. Matthew Bizzarro supervised the study, conceptualized and designed the study, supervised data collection, collected and analyzed data, drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. David R Peaper, Dr. Hanna Lee, Dr. Christine Puthawala conceptualized and designed the study, collected and analyzed data, drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Richard Feinn interpreted data, provided statistical analysis, drafted initial manuscript and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Michelle Rychalsky, reviewed and analyzed data, drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the regulations and guidelines of the Yale Human Research Protection program. The protocol was approved by the Yale Investigations Review Board with a waiver of informed consent (#2000032485).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, H., Fleiss, N., Bizzarro, M. et al. Factors associated with persistent bloodstream infection in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Perinatol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02460-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02460-5