Abstract

Primary results (median follow-up, 10.7 months) from the pivotal EPCORE® NHL-1 study in relapsed or refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) demonstrated deep, durable responses with epcoritamab, a CD3xCD20 bispecific antibody, when used as monotherapy. We report long-term efficacy and safety results in patients with LBCL (N = 157; 25.1-month median follow-up). As of April 21, 2023, overall response rate was 63.1% and complete response (CR) rate was 40.1%. Estimated 24-month progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were 27.8% and 44.6%, respectively. An estimated 64.2% of complete responders remained in CR at 24 months. Estimated 24-month PFS and OS rates among complete responders were 65.1% and 78.2%, respectively. Of 119 minimal residual disease (MRD)-evaluable patients, 45.4% had MRD negativity, which correlated with longer PFS and OS. CR rates were generally consistent across predefined subgroups: 36% prior chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, 32% primary refractory disease, and 37% International Prognostic Index ≥3. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were cytokine release syndrome (51.0%), pyrexia (24.8%), fatigue (24.2%), and neutropenia (23.6%). These results underscore the long-term benefit of epcoritamab for treating R/R LBCL with deep responses across subgroups, including patients with hard-to-treat disease and expected poor prognosis (ClinicalTrials.gov Registration: NCT03625037).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) is a heterogenous group of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas of which diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified is the most common [1,2,3]. LBCL is a curable disease, and patients with DLBCL who remain disease free for 2 years after front-line therapy have survival rates similar to the general population [4, 5]. However, outcomes are poor for patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) disease for whom transplant failed or who are transplant ineligible. In the SCHOLAR-1 pooled analyses of over 600 patients with R/R DLBCL, including those with high-risk features, median overall survival (OS) was 6.3 months [6]. T-cell and T-cell-engaging therapies have shown promising results in this setting [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], providing a potential option for patients with R/R DLBCL to enter long-term remission [14].

For patients with aggressive R/R B-cell lymphoma who have received at least two lines of prior systemic therapy, two classes of therapies that exploit T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity are now available: chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T) cells and bispecific antibodies [7,8,9,10,11, 15]. The use of CAR T-cell therapies is limited by patient eligibility, access, manufacturing consistency, need for lymphodepleting therapy, and adverse effects, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity for some products [3, 7,8,9, 15, 16]. Because T-cell-engaging bispecific antibodies generally have lower rates of severe CRS and neurotoxicity than CAR T-cell therapies and are available off the shelf [7,8,9, 15], they may have the potential to be a safer, faster, and more accessible treatment option. Long-term follow-up studies of T-cell-engaging bispecific antibody therapies are aimed at affirming response durability and impact on long-term outcomes, such as prolonging progression-free survival (PFS) and OS, as well as establishing long-term safety.

Epcoritamab is a subcutaneously administered CD3xCD20 bispecific antibody indicated for the treatment of adults with different types of R/R LBCL, including DLBCL, and follicular lymphoma after ≥2 lines of systemic treatment [17,18,19]. Following approval, the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) added epcoritamab as a preferred regimen in third and subsequent lines of treatment for patients with DLBCL [20].Footnote 1 In preclinical studies, epcoritamab demonstrated potent T-cell-mediated cytotoxic activity against CD20+ malignant B cells [21, 22] and higher potency compared with three other CD3xCD20 bispecific antibody constructs [21]. Epcoritamab is administered as a quick, low-volume subcutaneous injection. No bridging therapy or debulking is required prior to initiating epcoritamab treatment, allowing for rapid T-cell engagement and CD20 inhibition.

The ongoing phase 1/2 EPCORE® NHL-1 study of epcoritamab includes three parts in patients with R/R CD20+ LBCL after at least two prior lines of therapy (including anti-CD20 therapy): dose escalation [23], expansion [10], and optimization [24]. In the first disclosure of the expansion part (LBCL, N = 157) at a median follow-up of 10.7 months, the overall response rate (ORR) was 63.1% and the complete response (CR) rate was 38.9% [10]. Additionally, 45.8% of patients evaluable for minimal residual disease (MRD, n = 107) were MRD negative, and a correlation between MRD negativity and PFS was demonstrated [10]. The safety profile was manageable [10].

Here, we report long-term efficacy and safety results with >2 years of follow-up for patients with R/R LBCL. Results are also reported for the DLBCL and DLBCL or high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) subpopulations.

Materials/subjects and methods

Patients and treatment

The expansion part of the EPCORE NHL-1 trial (NCT03625037) was described previously [10]. In brief, patients ≥18 years of age with relapsed, progressive, and/or refractory mature B-cell lymphoma received subcutaneous epcoritamab 48 mg administered as a 1-mL injection once weekly in 28-day cycles 1–3 with step-up doses in cycle 1. Patients were hospitalized for 24 h after administration of the first full dose of epcoritamab. Corticosteroids were given 30–120 min before and for 3 consecutive days after the first four epcoritamab doses. Epcoritamab treatment continued once every 2 weeks in cycles 4–9 (days 1 and 15), and once every 4 weeks in cycle 10 and thereafter until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients who had a documented CD20+ mature B-cell neoplasm, had received at least two prior lines of systemic therapy, including at least one anti-CD20-containing regimen, and who were ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) or for whom prior ASCT had failed were enrolled.

Assessments

In the primary analysis, disease response and progression were assessed by an Independent Review Committee (IRC) in accordance with the Lugano classification [10, 25]. For the current analysis, protocol-specified analyses of ORR and PFS by IRC assessment, OS, MRD, and safety were carried out at a median follow-up of ~2 years. Efficacy analyses were also performed in prespecified subgroups, including age, baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, number of prior lines of therapy, prior CAR T-cell therapy, refractory to prior CAR T-cell therapy, prior ASCT, primary refractory disease, R/R to most recent prior anti-CD20 therapy, International Prognostic Index (IPI), and de novo or transformed DLBCL. Safety assessments included laboratory abnormalities and adverse events (AEs) as previously described [10].

Statistical analysis and endpoints

All efficacy and safety analyses were conducted in the full analysis population (all patients who received at least one dose of epcoritamab). ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who had best overall response of CR or partial response (PR). Best overall response per response criteria before initiation of subsequent antilymphoma therapy was summarized. ORR was based on IRC-assessed response per Lugano criteria. The ORR and CR rate and their corresponding 95% exact confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated based on the Clopper–Pearson method.

PFS was defined as time from day 1 of cycle 1 to first documented disease progression or death by any cause, whichever occurred earlier. Patients who remained alive without disease progression at the cutoff date were censored at the date of last disease assessment before the start of subsequent antilymphoma therapy. For patients who remained alive with incomplete or no baseline tumor assessment, PFS was censored on day 1 of cycle 1.

Time-to-event endpoints (duration of response, duration of complete response [DOCR], PFS, and OS) were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method with survival probabilities at scheduled visits, median time to event and 95% CI (where available; calculated using Brookmeyer and Crowley method with log-log transformation), and number and percentage of patients with an event or censoring reported. A landmark analysis was conducted for PFS and OS by MRD-negativity status up to cycle 3 day 1. This protocol-specified time point was selected because most MRD-negative patients had MRD negativity by cycle 3 day 1 (day 60, considering ± 3-day window). Landmark analyses excluded patients who had an event or were censored before cycle 3 day 1. MRD negativity was assessed by next-generation sequencing in plasma ctDNA (clonoSEQ®; Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA, USA). AEs were summarized as number and proportion of patients with at least 1 event. Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients and treatment exposure

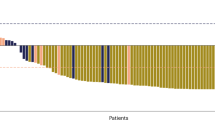

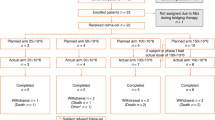

Between June 19, 2020, and October 1, 2021, 157 patients with LBCL were enrolled at 54 global sites and treated with epcoritamab. On April 21, 2023, the median follow-up was 25.1 months (95% CI, 24.0–26.0). Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline for the LBCL population are shown in Table 1 (Supplementary Table 1 provides details on the DLBCL [n = 139] and DLBCL or HGBCL [n = 148] subpopulations). The median age was 64.0 years and 59.9% were male. Patients had a median of 3 prior lines of therapy (range, 2–11), 95 patients (60.5%) had primary refractory disease, and 118 patients (75.2%) had disease refractory to two or more consecutive lines of therapy. The median time from initial diagnosis to first dose of epcoritamab was 1.6 years (19 months; range, 0.0–28.4 years). A total of 61 patients (38.9%) received prior CAR T-cell therapy, 46 of whom had progressive disease within 6 months of CAR T-cell therapy (i.e., CAR T-refractory; 29.3% of 157 patients with LBCL).

Of 157 patients with LBCL, 130 (82.8%) discontinued study treatment. Reasons for treatment discontinuation were: 89 (56.7%) disease progression, 23 (14.6%) AEs, 7 (4.5%) transplantation, 5 (3.2%) withdrawal by patient, 1 (0.6%) maximum clinical benefit (investigator determined the patient would not benefit from further therapy), and 5 (3.2%) for other reasons (2 investigator decision not further specified, 1 CAR T-cell therapy following PR to epcoritamab, 1 “good response” with AEs per investigator, 1 for frailty). Median time from cycle 1 day 1 to next antilymphoma therapy was 6.7 months (95% CI, 5.5–13.1). After epcoritamab treatment, 66 patients (42.0%) received antilymphoma therapy; 17 (10.8%) patients received radiotherapy and 47 (29.9%) proceeded to antineoplastic agents. Rituximab-based therapy (n = 26, 16.6%) was the most common systemic therapy, followed by CAR T-cell therapy (n = 12, 7.6%) and stem cell transplantation (n = 10, 6.4%; 9 allogeneic, 1 autologous; includes 2 patients who discontinued epcoritamab due to progressive disease and 1 patient who discontinued epcoritamab due to AE).

In cycle 1, all 157 patients received the first step-up dose (0.16 mg), 153 patients (97.5%) received the second step-up dose (0.8 mg), and 147 patients (93.6%) received the first full dose. Patients initiated a median of 5 cycles (range, 1–34; median, 15 doses [range, 1–49]) of epcoritamab. At data cutoff, 27 patients (17.2%) continued receiving study treatment and 21 (13.4%) patients had received epcoritamab for at least 24 months.

Efficacy

As of the data cutoff date, the ORR for patients with LBCL per IRC using Lugano criteria was 63.1% (n/N = 99/157; 95% CI, 55.0–70.6; Table 2). Median follow-up for DOR was 20.8 months (95% CI, 20.4–21.1). Median duration of response per the Kaplan–Meier estimate was 17.3 months (95% CI, 9.7–26.5; Table 2 and Fig. 1A).

The CR rate per IRC using Lugano criteria was 40.1% (n/N = 63/157; 95% CI, 32.4–48.2; Table 2). Median follow-up for DOCR was 20.3 months (95% CI, 16.7–20.7). Median time to CR was 2.6 months (range, 1.2–23.2) with most patients in CR by the first (week 6, n = 16) or second (week 12, n = 23) tumor assessment (n = 39 total). Eleven patients converted from PR to CR at or after the week 36 tumor assessment and as late as the week 96 tumor assessment. Per protocol, patients with tumor pseudo-progression were allowed to continue treatment with epcoritamab. Eleven patients with indeterminate response (by LYRIC criteria) or progressive disease (by Lugano criteria) had subsequent response by Lugano criteria, as assessed by IRC; 6 had durable CR and 5 of the 6 had MRD negativity in plasma preceding the Lugano CR. An estimated 64.2% of complete responders remained in CR at 24 months (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). Among 51 patients with a response at 8.4 months (week 36), 47 (90%) remained in response at 11.2 months (week 48) and 28 (54%) remained in response at 22.3 months (week 96) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Median PFS and OS were 4.4 months (95% CI, 3.0–8.8; Table 2 and Fig. 2A) and 18.5 months (95% CI, 11.7–27.7; Table 2 and Fig. 2B), respectively; estimated 24-month PFS and OS rates were 27.8% and 44.6%, respectively. Survival estimates among complete responders were higher than in the overall population, with estimated PFS and OS rates at 24 months of 65.1% (95% CI, 48.4–77.6; Table 2 and Fig. 2C) and 78.2% (95% CI, 65.4–86.7; Table 2 and Fig. 2D), respectively.

MRD negativity in the overall population was observed in 54 (45.4%; 95% CI, 36.2–54.8) of 119 MRD-evaluable patients treated with epcoritamab. An estimated 82.3% of these patients remained MRD negative at 6 months. An estimated 75.4% (95% CI, 57.9%–86.4%) of patients with MRD negativity had CR at 24 months. Of 30 MRD-evaluable patients in CR at week 96, an estimated 100% (95% CI, 88.4%–100.0%) were MRD negative. Most patients had MRD-negative status early, by cycle 3 day 1. A landmark analysis at cycle 3 day 1 of MRD-evaluable patients demonstrated that patients with MRD negativity had longer PFS (Fig. 3A) and OS (Fig. 3B) versus those who did not have MRD negativity.

Progression-free survival per IRC assessment (A) and overall survival (B) analysis by minimal residual disease assessment up to cycle 3 day 1 for patients with LBCL (N = 157). Landmark analyses excluded patients who had an event or were censored before cycle 3 day 1. C cycle, D day, IRC Independent Review Committee, LBCL large B-cell lymphoma, MRD minimal residual disease.

The CR rate with epcoritamab in predefined subgroups (Supplementary Table 2) was generally consistent with that observed in the overall population (40.1%; n/N = 63/157). The CR rate was 36% (95% CI, 24–49) in patients with prior CAR T-cell therapy and 43% (95% CI, 33–53) in CAR T-naive patients; 32% (95% CI, 22–42) in patients with primary refractory disease and 53% (95% CI, 40–66) in patients who did not have primary refractory disease; and 37% (95% CI, 27–49) in patients with IPI ≥ 3 and 45% (95% CI, 32–59) in patients with IPI 0–2.

Efficacy results in the DLBCL (n = 139) and DLBCL or HGBCL (n = 148) subpopulations (Supplementary Tables 3, 4 and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5) were similar to those observed in the LBCL population (N = 157).

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs observed with epcoritamab in the overall LBCL population (N = 157) are summarized in Table 3. The most common treatment-emergent AEs of any grade were CRS (51.0%), pyrexia (24.8%), fatigue (24.2%), neutropenia (23.6%), nausea (21.7%), anemia (21.0%), and diarrhea (21.0%). Fatigue occurred more frequently during the first 8 weeks (17.8%) of the study than during subsequent time periods (weeks 9–12, 3.5%; weeks 13–24, 4.0%; weeks 25–36, 3.1%; week 37 and thereafter, 8.8%). Neutropenia occurrence was consistent across study periods: 10.2% during the first 8 weeks and 7.7%–12.3% during the subsequent time periods. Grade ≥3 AEs were observed in 108 (68.8%) patients; treatment-related grade ≥3 AEs were observed in 53 (33.8%) patients. The most common treatment-related AEs regardless of grade were CRS (51.0%), injection-site reaction (19.7%), and neutropenia (18.5%; Supplementary Table 5). Epcoritamab induced rapid, sustained peripheral B-cell depletion in patients with detectable B cells at baseline. Likely due to margination, epcoritamab induced a transient decrease in peripheral T cells within 6–14 h of the first dose; this was followed by T-cell proliferation.

COVID-19-related AEs occurred in 37 (23.6%) patients. Grade 3 or 4 infections were reported in 40 (25.5%) patients with LBCL; the most common (≥2.0%) were COVID-19 (8.3%), pneumonia (3.2%), sepsis (3.2%), and COVID-19 pneumonia (2.5%). The percentage of patients with grade 3 or 4 infections excluding COVID-19 was higher during the first 12 weeks of the study (10.8%) than during subsequent time periods (1.9%–6.7% per analysis period).

Treatment-emergent AEs leading to discontinuation occurred in 23 patients (14.6%); 6 patients discontinued epcoritamab because of treatment-related AEs. An estimated 43.5% (range, 18.2%–66.7%) of responders who discontinued for AEs remained in CR or PR at 24 months. Eight patients who had ongoing CR discontinued due to AEs, and three remained in CR at 22 months. Three fatal AEs were considered related to epcoritamab by the investigator: one COVID-19 pneumonia, one bacterial pneumonia, and one immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome event that had multiple concurrent confounding factors [10].

No new immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, CRS, or clinical tumor lysis syndrome events occurred during extended follow-up. Overall, CRS occurred in 80 (51.0%) patients, with most events being grade 1 (grade 1: n = 50 [31.8%]; grade 2: n = 25 [15.9%]; grade 3: n = 5 [3.2%]); no grade 4 or 5 events were observed. Most CRS events occurred in cycle 1 after the first full dose (cycle 1 day 15) (Supplementary Fig. 6); the latest timepoint at which CRS occurred was cycle 4 day 1. Ten patients underwent repriming; in all ten cases, repriming occurred late in the treatment cycle (after cycle 11) and no patient experienced CRS after repriming. CRS resolved in most patients (n/n = 78/80; 97.5%), and the median time to resolution was 2 days. CRS was treated with tocilizumab in 23 (14.6%) patients and with corticosteroids (beyond those required for CRS prophylaxis) in 17 (10.8%) patients. Clinical tumor lysis syndrome (all grade 3) occurred in 2 patients in the first 8 weeks (onset on days 8 and 33) and was considered related to treatment.

Febrile neutropenia was observed in four patients (2.5%) and was considered treatment related in one patient (0.6%). Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was given to 23 of 49 (46.9%) patients who experienced neutropenia (neutropenia and decreased neutrophil count). Nineteen (12.1%) patients received concomitant immunoglobulins. The median immunoglobulin G level at baseline was 563 mg/dL (interquartile range, 392–762); after a small gradual decrease by cycle 2, median levels remained consistent over time (lowest median level on treatment was 420 mg/dL by cycle 18) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Discussion

Follow-up beyond 2 years from the expansion cohort of the EPCORE NHL-1 study continues to demonstrate deep and durable responses with epcoritamab monotherapy in a challenging-to-treat and refractory LBCL patient population. Responses continued to be durable with high 24-month estimates for probability of remaining in CR (64.2%) and survival of patients with CR (65.1% PFS rate, 78.2% OS rate). These results translate into favorable long-term outcomes as the PFS and OS Kaplan–Meier curves of patients with CR appear to be stabilizing. Most patients who achieved CR did so early, within 36 weeks. However, 11 of 63 (17.5%) patients first experienced a PR and subsequent deepening of response to CR at or beyond 36 weeks. Furthermore, patients with CR or MRD negativity tended to have longer PFS and OS compared with patients without CR or MRD negativity. Subgroup analyses showed CR benefits with epcoritamab regardless of IPI score, number of prior lines of treatment, or prior CAR T-cell therapy. These findings are encouraging for patient populations with challenging-to-treat disease who often have a poor prognosis.

The clinical activity of single-agent epcoritamab reported here is favorable relative to other approved treatment options considering the more refractory and difficult-to-treat population in EPCORE NHL-1 [26,27,28,29,30,31]. However, the number of patients at risk at long-term follow-up with epcoritamab in this study is not yet adequate for a meaningful comparison to CAR T-cell therapy outcomes. Although ORRs and CR rates for patients who receive CAR T-cell therapy are high (ORR up to 82%, CR up to 53%) [7,8,9], some patients cannot receive CAR T cells due to rapidly progressing disease that cannot wait for the required manufacturing time, and access can be limited when there are few trained, registered specialized treatment centers [3, 16]. Additionally, after CAR T-cell therapy, ≥39% of patients with R/R DLBCL experienced relapse and had poor outcomes [32]. In the present study, the percentage of patients with prior CAR T-cell therapy (38.9%) is among the largest reported to date in DLBCL or HGBCL.

The clinical activity and safety profile of epcoritamab reported here is in line with or favorable to that observed for other CD3xCD20 bispecific antibodies in similar patient populations. ORR and CR rates are comparable across the bispecifics, with differences being observed in long-term outcomes. In a study of glofitamab with median follow-up of 12.6 months, median OS was 11.5 months in patients with DLBCL [11]. In a study of odronextamab with median follow-up of 32.8 months, median OS was 9.2 months in patients with DLBCL [33]. Safety profiles were also comparable, with CRS being the most common treatment-emergent AE, occurring in 51% of patients in the present epcoritamab study, 64% in the glofitamab study (NCT03075696) [34], and 55% in the odronextamab study (NCT03888105) [33]; grade ≥3 CRS events were uncommon in all studies. Findings in the present study of epcoritamab with median follow-up of 25.1 months were favorable, with median OS of 18.5 months. Further, to our knowledge, this study includes the largest MRD-evaluable data set in R/R LBCL for a CD3xCD20 bispecific antibody to date and shows that deep and durable responses and early-onset MRD negativity are important and associated with favorable long-term outcomes. However, cross-trial comparisons should be made with caution due to differences in trial designs and patient populations, which can bias comparisons.

The proportion of patients with a treatment-emergent AE that led to treatment discontinuation was 14.6% (23/157). The percentage of high-grade (grade ≥3) infections remained between 1.9% and 6.7% during 12-week time periods after the first 12 weeks and, after an initial decrease, immunoglobulin G levels were maintained throughout the observation period. CRS remained low grade and manageable with most events confined to cycle 1. Notably, results from the ongoing cycle 1 optimization part of the study evaluating strategies for mitigating the risk of CRS in patients with R/R DLBCL treated with epcoritamab suggest that simple measures of prophylactic dexamethasone and hydration in cycle 1 reduce the frequency and severity of CRS [24]. Effective mitigation of CRS in cycle 1 could potentially allow a fully outpatient regimen for epcoritamab. An outpatient trial (NCT05451810) is currently ongoing.

This trial was conducted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic while the highly infectious Omicron variant was prevalent [35]. During the trial, pandemic-related social restrictions were relaxed or removed in many geographies. Increased risk and severity of infections, including COVID-19, have been associated with hematologic malignancies and their associated treatments, such as CD20-directed therapies like rituximab and bispecific antibodies [36,37,38,39,40,41]. COVID-19 infection rates reported in the current study were similar to that reported in a national Danish retrospective chart review where 33% of patients treated with bispecific antibodies had COVID-19 [42]. The Danish study’s cumulative incidence of COVID-19-related deaths in mostly vaccinated (95%) patients (6.4%) was consistent with that found in vaccinated patients with hematologic malignancies who were predominantly infected with Omicron variants (9.3%) [42, 43]. It is possible that the pandemic may have affected outcome measures like PFS and OS in our trial, e.g., because of COVID-19-associated deaths. Therefore, the timing of study and potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and Omicron variant should be considered when putting the results of this trial into context.

Limitations of the EPCORE NHL-1 study include its open-label, single-arm design and the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the enrolled study population. It should also be noted that this study was initiated before the 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours (WHO-HAEM5) was released in 2022. Compared with the revised 4th edition, DLBCL not otherwise specified, HGBCL not otherwise specified, and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma remained unchanged, but HGBCL with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements was redefined to DLBCL/HGBCL with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements and follicular lymphoma grade 3B was renamed to follicular LBCL in the WHO-HAEM5 [44].

In conclusion, T-cell engagement, quick onset of efficacy, and deep, durable responses, including MRD negativity, led to favorable long-term PFS and OS outcomes that, when combined with a manageable safety profile, support the use of epcoritamab in patients with R/R LBCL. The potential plateaus of the DOCR, PFS, and OS curves for patients with CR alongside the durable MRD-negative responses are highly encouraging and underscore the potential benefit of epcoritamab monotherapy in patients with R/R LBCL.

Data availability

De-identified individual participant data collected during the trial will not be available upon request for further analyses by external independent researchers. Aggregated clinical trial data from the trial is provided via publicly accessible study registries/databases as required by law. For more information, please contact ClinicalTrials@genmab.com.

Notes

Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology® [NCCN Guidelines®] for B-Cell Lymphomas V.1.2024. Accessed February 26, 2024. ©National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2024. All rights reserved. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

References

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–90.

Wienand K, Chapuy B. Molecular classification of aggressive lymphomas-past, present, future. Hematol Oncol. 2021;39:24–30.

Sehn LH, Salles G. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:842–58.

Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Jais JP, Witzig TE, Haioun C, Thompson CA, et al. Event-free survival at 24 months is a robust end point for disease-related outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1066–73.

Jakobsen LH, Bøgsted M, Brown PN, Arboe B, Jørgensen J, Larsen TS, et al. Minimal loss of lifetime for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in remission and event free 24 months after treatment: a Danish population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:778–84.

Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, Van Den Neste E, Kuruvilla J, Westin J, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017;130:1800–8.

Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56.

Abramson, Palomba JS, Gordon LI ML, Lunning MA, Wang M, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396:839–52.

Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–44.

Thieblemont C, Phillips T, Ghesquieres H, Cheah CY, Clausen MR, Cunningham D, et al. Epcoritamab, a novel, subcutaneous CD3xCD20 bispecific T-cell-engaging antibody, in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: dose expansion in a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2238–47.

Dickinson MJ, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, Bachy E, Corradini P, Iacoboni G, et al. Glofitamab for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2220–31.

Schuster SJ, Tam CS, Borchmann P, Worel N, McGuirk JP, Holte H, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of tisagenlecleucel in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas (JULIET): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1403–15.

Neelapu SS, Jacobson CA, Ghobadi A, Miklos DB, Lekakis LJ, Oluwole OO, et al. Five-year follow-up of ZUMA-1 supports the curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2023;141:2307–15.

Cappell KM, Kochenderfer JN. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:359–71.

van de Donk N, Zweegman S. T-cell-engaging bispecific antibodies in cancer. Lancet. 2023;402:142–58.

Myers GD, Verneris MR, Goy A, Maziarz RT. Perspectives on outpatient administration of CAR-T cell therapy in aggressive B-cell lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e002056.

Epkinly [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ, USA: Genmab US, Inc.; 2024.

Tepkinly [summary of product characteristics]. Ludwigshafen, Germany: AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG; 2023.

Epkinly [Japan package insert]. Minato-Ku, Tokyo, Japan: AbbVie GK, Genmab K.K.; 2023.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas v1. 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default_nojava.aspx.

Engelberts PJ, Hiemstra IH, de Jong B, Schuurhuis DH, Meesters J, Beltran Hernandez I, et al. DuoBody-CD3xCD20 induces potent T-cell-mediated killing of malignant B cells in preclinical models and provides opportunities for subcutaneous dosing. EBioMedicine. 2020;52:102625.

van der Horst HJ, de Jonge AV, Hiemstra IH, Gelderloos AT, Berry DRAI, Hijmering NJ, et al. Epcoritamab induces potent anti-tumor activity against malignant B-cells from patients with DLBCL, FL and MCL, irrespective of prior CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:38.

Hutchings M, Mous R, Clausen MR, Johnson P, Linton KM, Chamuleau MED, et al. Dose escalation of subcutaneous epcoritamab in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: an open-label, phase 1/2 study. Lancet. 2021;398:1157–69.

Vose JM, Feldman T, Chamuleau MED, Kim WS, Lugtenburg P, Kim TM, et al. Mitigating the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS): preliminary results from a DLBCL cohort of EPCORE NHL-1 [poster 1729]. Annual Meeting and Exposition of the American Society of Hematology; 9–12 December 2023; San Diego, CA.

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–68.

Smith SD, Lopedote P, Samara Y, Mei M, Herrera AF, Winter AM, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin for relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma: a multicenter post-marketing analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:170–5.

Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, Kamdar MK, McMillan A, Hertzberg M, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:155–65.

Salles G, Duell J, González Barca E, Tournilhac O, Jurczak W, Liberati AM, et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): a multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:978–88.

Kalakonda N, Maerevoet M, Cavallo F, Follows G, Goy A, Vermaat JSP, et al. Selinexor in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (SADAL): a single-arm, multinational, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e511–e522.

Caimi PF, Ai W, Alderuccio JP, Ardeshna KM, Hamadani M, Hess B, et al. Loncastuximab tesirine in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LOTIS-2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:790–800.

Nowakowski GS, Yoon DH, Peters A, Mondello P, Joffe E, Fleury I, et al. Improved efficacy of tafasitamab plus lenalidomide versus systemic therapies for relapsed/refractory DLBCL: RE-MIND2, an observational retrospective matched cohort study. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:4003–17.

Di Blasi R, Le Gouill S, Bachy E, Cartron G, Beauvais D, Le Bras F, et al. Outcomes of patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma after failure of anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy: a DESCAR-T analysis. Blood. 2022;140:2584–93.

Ayyappan S, Kim WS, Kim TM, Walewski J, Cho S-G, Jarque I, et al. Final analysis of the phase 2 ELM-2 study: odronextamab in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; 9–12 December 2023; San Diego, CA.

Hutchings M, Stella CC, Morschhauser F, Falchi L, Bachy E, Cartron G, et al. Glofitamab monotherapy in relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma: Extended follow up from a pivotal phase II study and subgroup analyses in patients with prior chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy and by baseline total metabolic tumor volume [oral presentation]. Annual Meeting and Exposition of the American Society of Hematology; 9–12 December 2023; San Diego, CA.

Sabbatucci M, Vitiello A, Clemente S, Zovi A, Boccellino M, Ferrara F, et al. Omicron variant evolution on vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31:1779–88.

García-Suárez J, de la Cruz J, Cedillo Á, Llamas P, Duarte R, Jiménez-Yuste V, et al. Impact of hematologic malignancy and type of cancer therapy on COVID-19 severity and mortality: lessons from a large population-based registry study. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:133.

Hardy N, Vegivinti CTR, Mehta M, Thurnham J, Mebane A, Pederson JM, et al. Mortality of COVID-19 in patients with hematological malignancies versus solid tumors: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23:1945–59.

Langerbeins P, Hallek M. COVID-19 in patients with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2022;140:236–52.

Lee CM, Choe PG, Kang CK, Jo HJ, Kim NJ, Yoon SS, et al. Impact of T-cell engagers on COVID-19-related mortality in B-cell lymphoma patients receiving B-cell depleting therapy. Cancer Res Treat. 2024;56:324–33.

Nachar VR, Perissinotti AJ, Marini BL, Karimi YH, Phillips TJ. COVID-19 infection outcomes in patients receiving CD20 targeting T-cell engaging bispecific antibodies for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2023;102:2635–7.

Villasboas JC, Kim TM, Taszner M, Novelli S, Cho S-G, Merli M, et al. Results of a second, prespecified analysis of the phase 2 study ELM-2 confirm high rates of durable complete response with odronextamab in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) follicular lymphoma (FL) with extended follow-up [abstract]. Blood. 2023;142:3041.

Kyvsgaard ER, Riley C, Clausen MR, Harsløf M, Heftdal LD, Niemann CU, et al. Low mortality from COVID-19 infection in patients with B-cell lymphoma after bispecific CD20xCD3 therapy. Br J Haematol. 2024;204:356–60.

Jiménez M, Novoa Jáuregui S, Fernández-Naval C, Bosch Schips M, Muzio S, Navarro Garcés V, et al. Clinical impact of Sars-Cov-2 vaccination in COVID-19 outcomes in patients diagnosed with hematologic malignancies: real-world evidence of two years of pandemic [abstract]. Blood. 2022;140:2628–30.

Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1720–48.

Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Turtle CJ, Brudno JN, et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:625–38.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for their participation in this study, as well as the study sites, investigators, data monitoring committee, and other research personnel. The authors thank Phillip Chen and Yan Liu for assistance with data analyses. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Laurie LaRusso, MS, and Duprane Pedaci Young, PhD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Genmab A/S and AbbVie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH and PL designed the trial; CT, YHK, HG, CYC, MRC, DC, WJ, YRD, RG, DJL, TMK, MvdP, MLP, TF, KML, AS, MH, TP, and PL were study investigators, provided patients or study materials, collected and assembled data; CT, YHK, HG, CYC, MRC, DC, WJ, YRD, RG, DJL, TMK, MvdP, MLP, TF, KML, AS, MH, MHD, NK, DS, TM, MS, TP, and PL analyzed and interpreted the data; all authors prepared the manuscript; and all authors participated in the critical review and revision of this manuscript and provided approval of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CT reports research funding from BMS, Hospira, and Roche; consulting role for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Cellectis, Gilead Sciences, Kite, Novartis, and Roche; honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Bayer, Cellectis, Gilead Sciences, Incyte, Janssen, Kite, Novartis, and Takeda; membership on an entity’s board of directors or advisory committees at AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Cellectis, Gilead Sciences, Incyte, Janssen, Kite, Novartis, Roche, and Takeda; and travel expenses from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Cellectis, Gilead Sciences, Kite, Novartis, and Roche. YHK reports consulting/advisory role for AbbVie and ADC Therapeutics; travel expenses from Roche/Genentech; and research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Lilly/Loxo, Merck, Roche/Genentech, and Xencor. HG reports consulting role for Gilead and Roche; and honoraria from AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, and Roche. CYC reports consulting/advisory roles and honoraria from Roche, Janssen, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Lilly, BeiGene, Menarini, Dizal, AbbVie, Genmab, Sobi, BMS, and Regeneron; research funding from BMS, Roche, AbbVie, MSD, and Lilly; speakers bureau for Janssen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genmab, AbbVie, and Roche; and travel expenses from Lilly and BeiGene. MRC reports consulting role for AbbVie, Janssen, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Genmab, and Incyte; advisory role for AbbVie, Janssen, Gilead, and Genmab; and travel expenses from AbbVie, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Genmab, Roche, and Pfizer. DC reports research grants (paid to institution, Royal Marsden Hospital) from MedImmune/AstraZeneca, Clovis, Lilly, 4SC, Bayer, BMS, and Roche. WJ reports research funding and consulting role for AbbVie and Roche. YRD reports no conflicts of interest. RG reports honoraria from MSD, Otsuka, Novartis, Astellas, Janssen, AbbVie, and Takeda. DJL reports consulting/advisory role for Janssen, Lilly, Roche, BeiGene, and Kite. TMK reports consulting for Amgen, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Boryung, Daiichi Sankyo, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd/Genentech, HK inno.N, Janssen, Novartis, Regeneron, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and Yuhan; honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, IMBdx, Janssen, and Takeda; and membership on an entity’s board of directors or advisory committees at Amgen, BeiGene, Janssen, Novartis, Regeneron, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda. MvdP reports no conflicts of interest. MLP reports no conflicts of interest. TF reports consulting role for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Epizyme, Genmab, Gilead/Kite, Karyopharm, and Takeda; and consulting role/speakers bureau for Seagen. KML reports membership on the Epcoritamab Global Council for Genmab; consulting/advisory role for AbbVie, BeiGene, BMS, Genmab, Kite/Gilead, and Roche; speakers bureau for AbbVie and BMS; research funding (paid to institution) from AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, CellCentric, Genmab, Janssen, Kite/Gilead, MorphoSys, MSD, Nurix, Regeneron, Roche, Step Pharma, and Viracta; and travel expenses from BMS. AS reports consulting role for Takeda, BMS, Novartis, Janssen, MSD, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Kite, and Mundipharma; honoraria from Takeda, BMS, Novartis, Janssen, MSD, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, and Kite; membership on an entity’s board of directors or advisory committees for Takeda, BMS, Novartis, Janssen, Amgen, Bluebird, Sanofi, and Kite; travel expenses from Takeda, BMS, and Roche; research funding from Takeda; and speakers bureau for Takeda, BMS, Novartis, Janssen, MSD, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, and Kite. MH reports scientific advisory boards for AbbVie, BMS, Genmab, Janssen, Roche, and Takeda; and research support (paid to institution) from BMS, Genentech, Genmab, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, Roche, and Takeda. MHD reports employment with AbbVie. NK reports employment with Genmab. DS reports employment with Genmab. TM reports employment with Genmab. MS reports employment with Genmab. TP reports consulting/advisory role for Pfizer/Seagen, Pharmacyclics, Incyte, Genentech, Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Curis, Kite/Gilead, BMS, Genmab, TG Therapeutics, and ADC Therapeutics; honoraria from Pfizer/Seagen and Lymphoma & Myeloma Connect; research funding from AbbVie, Pharmacyclics/Janssen, and Bayer; and is a scholar in the Clinical Research of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. PJL reports research grants from Takeda and Servier; advisory honoraria from BMS, Roche, Takeda, Genmab, AbbVie, Incyte, Regeneron, and Sandoz; and consultancy honoraria from Y-mAbs Therapeutics.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial was conducted in accordance with regulatory requirements, International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by site-specific Institutional Review Boards and/or Institutional or Central Ethics Committees (Central Ethics Committee: Hôpital Saint-Antoine Comité de Protection des Personnes [CPP] Ile de France V; Paris, France; 2017-001748-36), and all patients provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thieblemont, C., Karimi, Y.H., Ghesquieres, H. et al. Epcoritamab in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma: 2-year follow-up from the pivotal EPCORE NHL-1 trial. Leukemia 38, 2653–2662 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02410-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02410-8

This article is cited by

-

Targeting myeloid cells for hematological malignancies: the present and future

Biomarker Research (2025)

-

Immunotherapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: advances and challenges

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2025)

-

Bispecific antibodies: unleashing a new era in oncology treatment

Molecular Cancer (2025)

-

Bispecific Antibodies in Hematologic Malignancies: Attacking the Frontline

BioDrugs (2025)

-

The Improving Outcomes in Relapsed-Refractory Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: The Role of CAR T-Cell Therapy

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2025)