Abstract

Deleterious germline DDX41 variants are the leading cause of heritable predisposition to myelodysplastic neoplasia and acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML). Accurate classification of pathogenicity is crucial for managing patients and their families. The absence of specific guidelines, along with late-onset disease, incomplete penetrance, and founder variants, poses challenges in clinical and laboratory practice. We aggregated a synthetic cohort (ASC) of DDX41 germline and somatic variants from 35 studies, including 1796 cases among 53686 patients, plus an additional 832 cases from non-cohort publications. We aimed to leverage the DDX41-ASC to develop and refine ACMG/AMP criteria on case enrichment (PS4), somatic associations (PP4), and computational prediction (PP3/BP4). Analysis confirmed that deleterious germline DDX41 variants are most common in MDS/AML. A quasi-case-control study with ancestry matching revealed overestimated odds ratios for variants in underrepresented groups. Exploiting germline–somatic associations, we developed a Bayesian multinomial model that updates the odds of pathogenicity based on the presence and number of somatic patterns. Comparison of prediction tools showed that AlphaMissense outperformed REVEL in sensitivity. These results were integrated into an online tool to facilitate the consistent application of criteria. Overall, this comprehensive analysis of DDX41-ASC provides an evidence framework to inform the development of DDX41-specific curation guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deleterious germline variants in DDX41 are the most common cause of hereditary predisposition to myelodysplastic neoplasia (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), accounting for ~80% of known germline predisposition cases and up to 5% of all newly diagnosed cases [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Testing for the presence of DDX41 variants is now standard diagnostic practice [9,10,11] and included in many clinical sequencing panels used in the diagnosis of myeloid malignancies. Identification of causative germline DDX41 variants has important clinical implications, including for diagnostic classification, disease prognosis, stem cell donor selection, prophylaxis for graft versus host disease, predictive testing of family members, and informing long-term monitoring strategies [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

The diagnosis of DDX41-related hematologic malignancy predisposition syndrome (MONDO 0014809) relies on accurate classification of variant pathogenicity. DDX41 variants are typically classified into five categories: benign (B), likely benign (LB), variant of uncertain significance (VUS), likely pathogenic (LP), and pathogenic (P) according to the joint American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and Association of Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) criteria [19]. This framework considers genomic, biological, functional, and population evidence. To further facilitate variant classification, the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) provides gene-specific guidance on applying ACMG/AMP criteria. Clinical laboratories are encouraged to submit germline variant classifications to an open-source resource, ClinVar. To date, the Myeloid Malignancy Variant Expert Panel has specified curation rules for RUNX1 [20, 21], but no such guidelines exist yet for DDX41, so individual laboratories lack consensus on variant classifications.

DDX41 presents several challenges in variant interpretation as a result of: (i) late-onset disease, (ii) incomplete penetrance, (iii) the presence of founder variants, and (iv) the absence of validated functional assays. Conversely, DDX41 also provides opportunities for unique contributions to pathogenicity, including the specificity of somatic findings as well as a large number of published cohort studies that focus on this group of patients. Given these challenges and opportunities in variant classification, we aimed to establish an aggregated synthetic cohort of DDX41 variants (DDX41-ASC) from the published literature to study refinements to variant classification. Through this DDX41-ASC, we aimed to examine the connection between germline DDX41 variants and disease contexts, conduct a comprehensive quasi-case-control analysis with ancestry group matching, apply novel statistical modeling to somatic variant data, and evaluate the performance of in silico tools for variant effect prediction. These results will lay the foundation for developing DDX41 curation rules that can be applied internationally to ensure consistent variant classification worldwide.

materials/subjects and methods

Literature review

A literature review using the keyword “DDX41” on August 17, 2024, across PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase identified 819 references, with an additional 17 through cross-referencing. Ultimately, 35 studies involving 53716 consecutive patients with hematological malignancies or cytopenias met the criteria for case-control series (Table S1A). Additionally, 595 cases from 55 more studies, and 250 cases from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre [17] were included for data on the somatic DDX41 variant(s) (Table S1B). All reported DDX41 variants were extracted using HGVSc nomenclature whenever possible and uniformly reclassified according to modified ACMG/AMP criteria, irrespective of the classifications reported in the source publications (Supplementary Methods).

Quasi-case-control analysis

For cases reported in the literature, the reported ethnicity was used as a proxy for genetic ancestry (Table S1A). Population databases (controls) used for comparison against affected individuals with germline DDX41 included the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) v4.1.0 [22], ToMMo 54KJPN v20230626 (by the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization) [23], and Korean Variant Archive v2 (KOVA) [24] (Supplementary Methods).

Odds of pathogenicity

While we could apply the method of Maierhofer et al. [3] to infer the probability from (non-random) associations between germline and somatic variants using Bayesian reasoning, concern is warranted when applying this method to small samples of a specific germline variant under evaluation. Here, we developed a more stringent test for pathogenicity suitable for small sample sizes. For each germline variant, the posterior probability of observing different somatic DDX41 variants was estimated via a multinomial distribution (Supplementary Methods). Odds of pathogenicity (OddsPath) are calculated from Tavtigian et al.’s formula, with evidence levels: very strong (≥350), strong (≥18.7), moderate (≥4.33), and supporting (≥2.08) [25]. All cases from published cohorts and our laboratory were included, regardless of diagnosis. To avoid double-counting somatic hit data from non-cohort studies, we included all cases without a somatic hit and only counted cases with unique somatic hits not reported in cohorts.

Statistical analyses

The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for numerical variables. Prevalence estimates were shown as point estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs were calculated with Haldane correction [26]. The lower bound of the 95% CI was used to determine the strength of pathogenicity based on log10(2.08) [25]. Decision trees for variant classification were built using recursive partitioning (rpart version 4.1.23; Supplementary Methods). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to compare the performance of computational predictive tools (pROC version 1.18.5). Lollipop plots were created using ProteinPaint [27] with the protein domains based on Makishima et al. [2]. The analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Aggregation of existing DDX41 variant literature

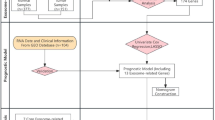

After excluding B and LB variants, duplicate cases, and variants with incomplete information, the existing peer-reviewed literature (see Methods) was compiled into the DDX41-ASC, comprising 1796 cases with DDX41 variants from 53686 consecutive patients, along with an additional 832 cases from non-cohort studies (Fig. 1A). 25% of cases were reported to have a germline origin confirmed. A total of 450 distinct variants were identified, including 65 variants (14%) found only in non-cohort studies (Fig. 1B). Missense variants showed the most diverse range with 261 different variants (including five with unclassified pathogenicity due to missing variant information), followed by frameshift (n = 67), nonsense (n = 38), and canonical splice site (n = 37) variants (Fig. 1C).

A Flow diagram illustrating the literature review process for identifying published DDX41 variants, with a cut-off date of 17-Aug-2024. *A single-center study cohort was reported in two separate publications. **Cases from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (PMCC) were published in Wells et al. [17]. B Distribution of 450 distinct germline DDX41 variants across the cohort sources. C Number of distinct DDX41 variants by variant type.

All variants are summarized and ranked using a recursive partitioning decision tree (Fig. S1). The co-occurrence of somatic DDX41 hotspots (evidence code PP4) and enrichment in MDS/AML cases (PS4) were key criteria contributing to classification across all variant types. Five nonsense/frameshift variants were classified as LP based on the combination of PVS1 and absence in population controls (PM2_supporting) [28]. Curation of missense variants using baseline approaches resulted in most variants (n = 233 [87%]) being classified as VUS.

Given the significant proportion of variants classified as VUS, we aimed to leverage the DDX41-ASC to develop and refine existing ACMG/AMP criteria concerning case enrichment (PS4), somatic associations (PP4), and computational prediction (PP3/BP4).

Enrichment of DDX41 variants in MDS/AML (PS4)

To understand the prevalence of DDX41 variants across different disease contexts, we included a subset of patients from the DDX41-ASC with a diagnosis of MDS/AML (n = 34051), other myeloid neoplasms (n = 8072), unexplained cytopenias (n = 5156), and lymphoid neoplasms (n = 1228); 5179 individuals with aplastic anemia or unspecified hematologic malignancies were excluded. Among the 1594 cases with a germline DDX41 variant, we excluded 17 with aplastic anemia or healthy carriers, along with four cases with unclassified variants due to missing information, leaving 1573 cases included in the analysis.

Overall, a germline P/LP/VUS variant was found in 4.0% of MDS/AML cases, 2.9% of lymphoid neoplasms, 1.4% of other myeloid neoplasms, and 1.3% of cases with cytopenias (Fig. 2A). Notably, 7 cases had a diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasm in addition to MDS/AML (n = 6) or another myeloid neoplasm (n = 1), and 6 MDS/AML cases had two germline variants, each being P/LP and VUS. A germline P/LP variant was found in 3.2% of MDS/AML cases (95% CI: 3.0–3.4%), which is significantly higher than in other diseases. The presence of a DDX41 VUS was more common in lymphoid neoplasms (2%) compared to other diagnoses (0.7 to 1.0%). Among all reported germline variants, patients with MDS/AML had the highest proportion of P/LP variants (79%), followed by cases with unexplained cytopenias (45%), lymphoid neoplasms (29%), and other myeloid neoplasms (26%).

A The proportion (%) of cases with pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) or uncertain (VUS) DDX41 variants across various disease contexts in the literature cohorts. Whiskers indicate the 95% confidence interval. Twelve cases had two germline variants (6 with both VUS and P/LP were counted twice), and 7 cases had a lymphoid neoplasm in addition to either MDS/AML (n = 6) or another myeloid neoplasm (n = 1) (counted twice). Pairwise Fisher’s exact tests were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. P-value annotations: <0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), < 0.0001 (****). B The stacked bar chart illustrates the distribution of 1374 germline DDX41 variants in 1366 MDS/AML cases across different classes of pathogenicity. Two cases were unclassified due to missing HGVSc information and were excluded. Ten cases harbored two germline variants: 6 were VUS + P/LP, 3 were both VUS, and 1 was both LP. Variant counts for each classification are shown below each bar. C Quasi-case-control analysis of germline DDX41 variants in patients with MDS/AML compared to population controls, differentiated by overall and ancestral groups (non-Finnish European [NFE] versus East Asian [EAS]). Variants with at least 10 total cases, 3 occurrences within the EAS ancestry group, and 5 NFE-only instances are included. The odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval are shown. Gray, blue, and red represent overall, NFE, and EAS ancestry groups, respectively, based on the exclusivity (or lack thereof) of variants within each ancestry group and the control group. Red circles to the left of the variant indicate downgraded variants due to added ancestry matching: PS4_moderate (two solid circles), PS4_supporting (single solid circle), or PS4_notmet (open red circle).

Among 1366 MDS/AML cases, we identified 1084 P/LP, 290 VUS, and 2 unclassified (missing HGVSc) germline DDX41 variants; 10 cases carried two germline variants (6 were VUS + P/LP, 3 were both VUS, and 1 was both LP). In total, 1374 variants corresponding to 324 distinct changes are summarized in Fig. S2. The most common types of P variants were frameshift (43%), start-loss (22%), and nonsense (17%). Missense variants were the most prevalent variant type in LP and VUS, accounting for 77.5% and 90% of cases, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Cases involving other myeloid neoplasms (myeloproliferative neoplasm [MPN; n = 50], MDS/MPN [n = 13], unspecified [n = 48]) or unexplained cytopenias (n = 69) revealed 103 distinct germline variants, with the M155I variant being the most common (8%). Notably, 70 variants occurred only once (Fig. S3A), and 10 cases had somatic-only DDX41 variants. There was a limited number of patients with lymphoid neoplasms across seven studies: 25 with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and 17 mature B-cell neoplasms [1, 7, 27, 29,30,31,32]. Of these, 35 had a germline variant, whereas seven had somatic-only DDX41 variants (Fig. S3B). Eight also had myeloid neoplasms: MDS/AML (n = 7) and therapy-related MDS/MPN (n = 1). The R164W variant, previously speculated to be associated with lymphoma [33], was found in three patients: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) with pancytopenia, gamma heavy chain disease/MYD88-negative LPL, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n = 1 each).

Ancestry group-specific variability of DDX41 variant enrichment (PS4)

After confirming the significant association between germline DDX41 variants and MDS/AML, we conducted a quasi-case-control study of specific variants in MDS/AML cases versus population controls (see “Methods”). We focused on variants with at least ten cases, three occurrences in the East Asian (EAS) ancestry group, and/or five non-Finnish European (NFE)-only instances (Fig. 2C and Table S2). The odds ratios for NFE-specific variants were generally consistent across overall and ancestry-specific data, except when NFE had a lower allele frequency than another group, such as for R479Q (0.03% in Admixed American versus 0.003% in NFE).

Using gnomAD total allele counts overestimated the OR of EAS ancestry variants. As a result of added ancestry matching, the PS4 criterion strengths were adjusted: from strong to moderate (A500fs, E7*, V152G, Y259C), moderate to supporting (F183S, T360fs), and moderate to not met (E256K) (Fig. 2C).

Overall, eight variants showed a strong association with MDS/AML, with the lower bound of the 95% CI ≥ 18.7: L283fs, Y340N, Q208E, A191T, V445del, S363del, R311*, and K331del. The two most common germline variants, c.3G>A and D140fs, were moderately enriched in MDS/AML cases (≥4.33), along with 12 other variants. Three variants met the PS4_supporting criterion (≥2.08).

Characteristics of somatic DDX41 variants (PP4)

The presence of somatic DDX41 variants is a characteristic feature in DDX41-related hematologic malignancy predisposition syndrome [3]. We further characterized the observed somatic variants using the DDX41-ASC, which includes 34051 individuals with MDS/AML, of whom 1552 cases had a DDX41 variant, including 828 with both germline and somatic variants, 538 with germline-only, and 186 with somatic-only DDX41 variants.

We initially analyzed MDS/AML cases that included both germline and single somatic DDX41 variants (n = 799 cases; one excluded for missing data). As expected, R525H was the most common somatic variant (n = 533; 66.7%). This was followed by six recurrent missense variants: G530D (c.1589G>A; 6.4%), P321L (c.962C>T; 4.1%), T227M (c.680C>T; 2.6%), E345D (c.1035G>C or c.1035G>T; 1.8%), G530S (c.1589G>A; 1.4%), and D344E (c.1032C>G or c.1032C>A; 1.4%) (Fig. 3A). The remaining 15.6% of cases harbored 75 different DDX41 variants, each with up to six instances in less than 1% of cases. Missense variants were the most common, comprising 99% of all somatic variants; six were in-frame variants, and three were truncating variants (Fig. S4A). We observed significant differences in the median variant allele fractions (VAFs) among the somatic DDX41 variants (Fig. S4B): P321L (23%), T227M (13.5%), D344E (9.7%), E345D (9.5%), G530D (8.9%), R525H (7.5%), and G530S (6%).

A The frequency of single DDX41 somatic variants observed alongside a germline DDX41 variant in 799 cases of MDS/AML. One case was excluded due to missing variant information. B The proportions of somatic DDX41 variant types among cases with or without a germline DDX41 variant. C, D The association between various somatic DDX41 variants and germline DDX41 variants in MDS/AML. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from a quasi-case-control study. Higher ORs indicate a higher prevalence of somatic variants among patients with MDS/AML who carry a germline DDX41 variant. Case counts represent the number of cases with each somatic variant type. E, F The correlation between the most prevalent germline DDX41 variants (occurring in at least 15 instances) and the types of somatic DDX41 variants.

We then examined the frequency of different types of somatic DDX41 variants among cases with and without a germline DDX41 variant (P, LP, and VUS). Among 1366 individuals with MDS/AML and a germline DDX41 variant, 538 (39%) had none, 800 (58.6%) had one, 27 (2%) had two, and one had three somatic DDX41 variants. In contrast, among the 32685 cases of MDS/AML without an identified germline DDX41 variant, somatic DDX41 variants were rarely found: a single variant in 139 cases (0.43%) of which 74 (0.23%) were a recurrent hotspot, and multiple variants in 47 cases (0.14%) (Table S3). In cases without a germline DDX41 variant where somatic DDX41 variants were present, they tended to be single non-recurrent or multiple variants compared to those with a germline DDX41 variant (Table S3 and Fig. 3B). Indeed, a single somatic DDX41 variant was strongly linked to a germline P/LP/VUS DDX41 variant (OR = 346, 95% CI: 282–428) (Fig. 3C). This association was even stronger when R525H was considered alone (OR = 482, 95% CI: 362–632) or only recurrent non-R525H (OR = 1203, 95% CI: 561–2915) somatic variants (Fig. 3D). Other single non-recurrent or multiple somatic variants remained significantly associated with a germline variant, though to a lesser degree (Fig. 3C).

The association between recurrent somatic DDX41 variants was consistent across the well-established P/LP germline DDX41 variants (Fig. 3E, F). Among the three most frequent germline DDX41 variants—c.3G>A, D140fs, and A500fs (combined n = 453)—a single somatic R525H variant was found in 45–52% of cases, single recurrent non-R525H missense variant in 6–10%, single non-recurrent variant in 9–12%, and multiple somatic variants in 0–1% (Fig. 3E). This pattern is similarly observed for other less common but recurring germline P/LP DDX41 variants (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the M155I variant (classified as a VUS; gnomAD frequency 0.04%) was observed only once with a single non-recurrent somatic DDX41 variant. The association with other less common germline variants is summarized in Fig. S5.

The variant details of 186 cases of MDS/AML with somatic-only DDX41 variants are summarized in Fig. S6. Among 139 cases with a somatic-only DDX41 variant, 91% were missense, but recurrent non-R525H missense variants were rare. One case had three somatic-only DDX41 variants: L87V, Y451C, and G586R. The remaining 46 cases had two somatic-only variants: one missense (R525H in 67%) or in-frame, combined with either another missense/in-frame or truncating variant, with both combinations occurring equally (Fig. S6). When seen as single or double variants, the VAFs of (assumed) somatic-only DDX41 variants were similar to those with a germline variant (Fig. S7).

Overall, these findings support a specific association between deleterious DDX41 variants and the pattern of somatic second hits. In contrast, although somatic-only DDX41 variants can occur, they are much rarer and have different variant profiles.

Odds of pathogenicity from somatic DDX41 variants (PP4)

After observing a strong non-random association between germline and somatic DDX41 variants and building on previous work [3], we sought to evaluate the pathogenicity of germline DDX41 variants informed by the presence, number, and pattern of somatic variants. In cases of MDS/AML, the three most common pathogenic variants (c.3G>A, D140fs, and A500fs) were observed to have single recurrent missense (both R525H and non-R525H), single non-recurrent, and multiple somatic variants in 58%, 10%, and 0.7% of cases, respectively (Fig. 3E). In contrast, these somatic patterns were observed in 0.23%, 0.20%, and 0.14% of cases without a germline DDX41 variant (Fig. 3B). We calculated the posterior probability of pathogenicity and OddsPath [25] using a multinomial probability mass function, noting that an observation of an isolated case with a recurrent somatic hit has a posterior probability of 97% and an OddsPath of 252 (Fig. 4A), equivalent to a “strong” level of evidence for pathogenicity in the modifications suggested to the ACMG/AMP evidence framework [25, 34].

A Simulation of OddsPath based on the observed counts of single recurrent (R525H and non-R525H) somatic missense variants (n1), single non-recurrent somatic variants (n2), and multiple somatic hits (n3) among up to 25 evaluable cases (N) of germline DDX41 variants. B, C Contingency table and Sankey diagram comparing evidence strength levels between the original approach (modified from Maierhofer et al. [3] and OddsPath. In the Sankey diagram, 211 cases that do not meet both criteria are excluded.

Details of somatic occurrences of all 450 distinct germline DDX41 variants are provided in Table S4. Overall, 92 variants had an OddsPath ≥350, consistent with a “very strong” level of evidence (Fig. 4B, C). Twenty-five variants were upgraded from PP4_moderate to PP4_strong (n = 24) or very strong (n = 1): five from recognizing additional somatic hotspots, and the remaining from non-recurrent single or multiple somatic hits.

In contrast, eight variants had evidence downgraded based on OddsPath (Table S4). These included six with OddsPath <2.08: M155I (n = 39), K187R (n = 19), R219H (n = 12), R339L (n = 6), R525H (n = 5), and P321L (n = 5). For R525H or P321L, only two of five cases each had confirmed germline origin. Two variants (I207T and c.138+5G>T) were downgraded from PP4_strong to PP4_moderate because only one somatic hotspot was observed out of four evaluable cases. Notably, M155I and R219H had three and two single non-recurrent somatic hits, respectively, a pattern highly unlikely due to chance despite a low OddsPath (Fig. S8).

When calculating the OddsPath, it is essential to consider all evidence of somatic occurrences. Incorporating non-cohort cases resulted in a total of 55 upgrades, including 40 variants from an OddsPath of <2.08, to PP4_moderate (n = 1), strong (n = 33), and very strong (n = 6).

In silico tool comparison for missense variants (PP3/BP4)

Given the numerous missense DDX41 variants classified as VUS, we assessed the REVEL score [35] for missense variants and compared it with AlphaMissense [36]. After removing the PP3 criterion, only 21 missense variants remained as P/LP. Therefore, we used all germline missense variants co-occurring with a single recurrent somatic hit to create a pathogenic truth set (n = 61), excluding those within the splice junctions. We retrieved 678 missense variants from gnomAD v4.1.0. After curation, only four were LB, so we included 503 in the benign truth set, excluding 171 found in the DDX41-ASC.

Using the REVEL score, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve demonstrated an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.74–0.84), and the optimal REVEL score threshold (Youden’s index) was 0.33 (Fig. 5A). The performance of three REVEL thresholds (≥0.33, 0.64 [37] and 0.70 [3]) was compared in Table S5.

The ability to classify putative pathogenic (n = 61) and non-pathogenic (n = 503) variants, based on the presence of any concurrent single recurrent somatic variant, was evaluated and compared. A Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve based on REVEL scores. B ROC curve based on AlphaMissense scores. C Sankey diagram illustrating the classification of variants as pathogenic supporting, benign supporting, or not met, based on REVEL (≥0.7 and ≤0.3) and AlphaMissense scores (≥0.792 and ≤0.169), across 255 evaluable missense variants with varying levels of odds of pathogenicity (OddsPath, based on the presence of somatic DDX41 variant). Six missense variants are excluded due to missing HGVSc information (n = 5) or delins variant type (n = 1). Note that this is not the final PP3 or BP4 classification, which also considers the potential splicing impact (e.g., by SpliceAI score).

We then evaluated AlphaMissense’s ability to identify putative pathogenic variants. Alpha scores outperformed REVEL with an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.83–0.92; p < 0.001 by Delong test) (Fig. 5B). The performance of three AlphaMissense thresholds (pre-determined class [36], ≥0.792 [38] and 0.91 [Youden’s index]) was compared (Table S5). We chose the AlphaMissense scores ≥0.792 and ≤0.169 for PP3 and BP4, respectively, as recommended by ClinGen, for ongoing analysis. REVEL was better at identifying non-pathogenic variants, though there was significant overlap. Conversely, putative pathogenic variants clustered around high alpha scores (Fig. S9). Applied to DDX41-ASC (255 evaluable variants), AlphaMissense better identified variants with higher OddsPath (based on multinomial somatic hits), but had more false positives (Fig. 5C). Of 82 variants with OddsPath ≥4.33, 69 (84%) and 32 (39%) met PP3 by AlphaMissense and REVEL. Of 173 variants with OddsPath <2.08, 52 (30%) and 76 (44%) met BP4 by AlphaMissense and REVEL, respectively, while 54 (31%) and 28 (16%) met PP3.

Updated DDX41 variant classification

Finally, we integrated the above analysis to classify 438 evaluable germline DDX41 variants (Fig. 6). A total of 65 variants were upgraded: 34 from VUS (26 to LP and 8 to P), and 30 from LP to P. These included 32 missense variants initially classified as VUS, based on a combination of high OddsPath from observed somatic hits (PP4), supporting-to-moderate level of case enrichment (PS4) in MDS/AML, and predicted deleterious effects by AlphaMissense (PP3). Thirty-two variants with high PP4_OddsPath (8 moderate, 22 strong, and 2 very strong) remained classified as VUS, particularly affecting missense (n = 21) and in-frame (n = 5) variants, due to the lack of other applicable criteria.

Each of the 438 variants is shown on the x-axis (using abbreviated nomenclature), including start-loss (n = 4), frameshift (n = 67), nonsense (n = 38), canonical splice site (n = 37), intronic (n = 17), synonymous (n = 6), missense (n = 66) or in-frame (n = 3) pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP), and missense (n = 190) or in-frame (n = 10) variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Twelve variants were excluded: structural (n = 6), untranslated region (n = 1), and missing variant information (n = 5 missense variants). The applicable ACMG/AMP criteria are shown in each row, including the comparison between two PP4 approaches (modified from Maierhofer et al. [3]. [PP4(original)] versus odds of pathogenicity from multinomial probability [PP4(OddsPath)]) and PP3/BP4 approaches (REVEL [PP3/BP4(revel)] versus AlphaMissense [PP3/BP4(alpha)]). The asterisks (*) on PS4 indicate the revised strength of evidence based on matching for East Asian genetic ancestry. Comparisons are made between the original and updated pathogenicity classifications, with red and blue text indicating upgraded and downgraded variants, respectively. Note that five variants have two different HGVSc descriptions (listed from left to right in the order of appearance) and are shown twice: R53fs (c.155dup, c.156_157insA); M316fs (c.947_948del, c.946_947del); T529fs (c.1585dup, c.1586_1587del); G72R (c.214G>A, c.214G>C); and M155I (c.465G>C, c.465G>A).

We created an automated application that interfaces with the DDX41-ASC to support classification of pathogenicity according to ACMG/AMP criteria (https://blombery-lab.shinyapps.io/ddx41). In addition to calculating the odds ratio for case enrichment and OddsPath based on observed somatic hits, the application also features a customizable user interface, allowing users to specify disease contexts, second somatic hotspots, in silico tools for PP3/BP4 (REVEL or AlphaMissense), and thresholds for various curation criteria such as PS4, REVEL [35], SpliceAI [39], and population allele frequency. Each queried variant provides detailed information, including relevant literature and related somatic hits. Users can also manually override the criteria for pathogenicity classification. The application supports bulk curation of variants, enabling multiple variants to be curated simultaneously with the standardized application of pre-specified rules.

Discussion

Evidence-based and reproducible classification of DDX41 variants by clinical molecular pathology laboratories/services and researchers is critical for optimal patient management. To this end, we have comprehensively aggregated existing published data into a large synthetic cohort comprising 54518 total patients, 2628 total germline and somatic DDX41 cases, and 450 unique germline DDX41 variants. The DDX41-ASC has enabled analyses that have provided insights informing the evidence of pathogenicity as per existing variant curation frameworks (ACMG/AMP). An online curation tool was developed to query germline DDX41 variants, retrieve literature cases and somatic hit data, and apply standardized, yet customizable, curation rules for consistent interpretation across laboratories with a single click.

A hallmark of cancer predisposition genes is the significant enrichment in patients with a given phenotype compared to matched controls. Given the relatively high frequency of DDX41 variants in the population due to their minimal impact on reproductive fitness, very large case-control studies are required to study disease associations effectively. Although several large MDS/AML cohorts have been documented in the literature, gathering sufficient evidence to meet this criterion (PS4) requires labor-intensive manual review of publications. Furthermore, because founder variants are more common in certain ancestry groups, unadjusted case-control comparisons may overestimate enrichment. The creation of a DDX41-ASC enables the reproducible assessment of DDX41 variants with improved statistical accuracy.

One key characteristic of myeloid malignancy in the context of DDX41-related hematologic malignancy predisposition syndrome is the presence of a second somatic variant in DDX41. Several groups have relied on the presence of either recurrent (variously defined) or any somatic hit to inform variant pathogenicity [1, 8, 40, 41]. Our previous work demonstrated a highly non-random co-occurrence between deleterious germline and somatic DDX41 variants (posterior probability 99.8%), suggesting that such findings could help strengthen the PP4 criterion to a very strong level [3]. Current work refines the approach by incorporating the frequency with which a germline variant co-occurs with different (multinomial) somatic patterns, updating posterior probability and OddsPath dynamically. This method tackles the inevitable issue of somatic DDX41 variants coinciding with a given germline DDX41 variant, preventing false attribution of pathogenicity.

The use of computational (in silico) prediction tools, although mainly providing minor evidence of pathogenicity, can still significantly impact the final variant classification. Our analysis revealed that the commonly used REVEL score thresholds lacked sufficient sensitivity for identifying putative pathogenic missense variants in DDX41, resulting in under-classification in many instances. In contrast, AlphaMissense—a newer deep learning-based model—demonstrated superior diagnostic performance. Implementing AlphaMissense caused a significant shift in both PP3 and BP4 calls, with more variants reaching the PP3 threshold. This increased sensitivity did not compromise specificity when combined with other criteria, as no putative benign variants (lacking recurrent somatic hits) were incorrectly classified as P/LP.

Our work has several important limitations to acknowledge. This work relied on cases reported in the literature instead of re-analysis of raw sequencing data. Despite the large size of the aggregated cohort, data on non-MDS/AML cases, including lymphoid neoplasms, are limited and preclude any meaningful conclusions regarding the association between DDX41 germline predisposition and these entities. The absence of detailed ancestry information in many source publications hampers more precise quasi-case-control analysis. Most available data come from individuals of NFE and EAS ancestries, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other populations and highlights the need for more data from diverse ancestry groups. The variant and clinical data were manually extracted from various publications that vary in nomenclature, sequencing platforms, bioinformatic pipelines, and reporting standards. Therefore, intronic and structural variant types are almost certainly underrepresented. The frequency and number of concurrent somatic mutations would also vary with detection sensitivity. Most publications assumed the germline versus somatic origin of the DDX41 variants rather than basing this on direct evidence from paired testing with non-hematological tissue; misclassification could significantly affect the OddsPath, especially in rare cases. Since the model relies on data from known deleterious variants, it is not suitable for variants with lower penetrance or different somatic association patterns; further work is needed to refine the approach [42].

In summary, by creating a DDX41-ASC and related analyses, we have made multiple refinements in variant classification. These include an ancestry-matched quasi-case-control study for a more precise assessment of case enrichment, enhanced sophistication in incorporating DDX41 somatic variants into classification, and the identification of AlphaMissense as a potentially preferred computational tool for pathogenicity assessment over REVEL. Ongoing collaboration and data sharing will be essential to refine these recommendations further and help incorporate them into standard diagnostic practice, facilitated by a publicly available online tool, and to include non-European, non-East Asian groups, such as African and South Asian datasets. Our analysis of germline-somatic pairs and somatic VAFs may guide future functional studies in this germline predisposition entity.

We look forward to the incorporation of our work into ClinGen-approved DDX41 variant curation rules, which can be implemented broadly in clinical laboratories worldwide.

Data availability

Code available at https://github.com/blomberylab/ddx41.

References

Li P, Brown S, Williams M, White T, Xie W, Cui W, et al. The genetic landscape of germline DDX41 variants predisposing to myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2022;140:716–55.

Makishima H, Saiki R, Nannya Y, Korotev S, Gurnari C, Takeda J, et al. Germ-line DDX41 mutations define a unique subtype of myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2023;141:534–49.

Maierhofer A, Mehta N, Chisholm RA, Hutter S, Baer C, Nadarajah N, et al. The clinical and genomic landscape of patients with DDX41 variants identified during diagnostic sequencing. Blood Adv. 2023;7:7346–57.

Badar T, Nanaa A, Foran JM, Viswanatha D, Al-Kali A, Lasho T, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of somatic and germline DDX41 variants in patients and families with myeloid neoplasms. Haematologica. 2023;108:3033–43.

Bataller A, Loghavi S, Gerstein Y, Bazinet A, Sasaki K, Chien KS, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with myeloid malignancies and DDX41 variants. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:1780–90.

Bernard E, Tuechler H, Greenberg PL, Hasserjian RP, Arango Ossa JE, Nannya Y, et al. Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System For Myelodysplastic Syndromes. NEJM Evid 2022;1:EVIDoa2200008.

Tierens A, Kagotho E, Shinriki S, Seto A, Smith AC, Care M, et al. Biallelic disruption of DDX41 activity is associated with distinct genomic and immunophenotypic hallmarks in acute leukemia. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1153082.

Duployez N, Duchmann M, Largeaud L, Lambert J, Bidet A, Clappier E, et al. Prognostic significance of DDX41 germline mutations in intensively treated AML patients: an ALFA-Filo study. Blood. 2021;138:612.

Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1703–19.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasnicka HM, et al. International consensus classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: integrating morphological, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022;140:1200–28.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Myelodysplastic Syndromes (Version 2.2025). Available from https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mds.pdf [2025].

Dohner H, DiNardo CD, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, Dombret H, Ebert BL, et al. Genetic risk classification for adults with AML receiving less-intensive therapies: the 2024 ELN recommendations. Blood. 2024;144:2169–73.

Kobayashi S, Kobayashi A, Osawa Y, Nagao S, Takano K, Okada Y, et al. Donor cell leukemia arising from preleukemic clones with a novel germline DDX41 mutation after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2017;31:1020–2.

Gibson CJ, Kim HT, Zhao L, Murdock HM, Hambley B, Ogata A, et al. Donor clonal hematopoiesis and recipient outcomes after transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:189–201.

Saygin C, Roloff G, Hahn CN, Chhetri R, Gill S, Elmariah H, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant outcomes in adults with inherited myeloid malignancies. Blood Adv. 2023;7:549–54.

Bannon SA, Routbort MJ, Montalban-Bravo G, Mehta RS, Jelloul FZ, Takahashi K, et al. Next-generation sequencing of ddx41 in myeloid neoplasms leads to increased detection of germline alterations. Front Oncol. 2020;10:582213.

Wells C, Tiong IS, Hunter S, Den Elzen N, Goode E, Kankanige Y, et al. Genomic variation in DDX41 identified through clinical sequencing. Br J Haematol. 2025;207:1653–8.

Baliakas P, Tesi B, Cammenga J, Stray-Pedersen A, Jahnukainen K, Andersen MK, et al. How to manage patients with germline DDX41 variants: recommendations from the Nordic working group on germline predisposition for myeloid neoplasms. Hemasphere. 2024;8:e145.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Luo X, Feurstein S, Mohan S, Porter CC, Jackson SA, Keel S, et al. ClinGen myeloid malignancy variant curation expert panel recommendations for germline RUNX1 variants. Blood Adv 2019;3:2962-79.

Feurstein S, Luo X, Shah M, Walker T, Mehta N, Wu D, et al. Revision of RUNX1 variant curation rules. Blood Adv. 2022;6:4726–30.

Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, Collins RL, Kanai M, Wang Q, et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature. 2024;625:92–100.

Tadaka S, Katsuoka F, Ueki M, Kojima K, Makino S, Saito S, et al. 3.5KJPNv2: an allele frequency panel of 3552 Japanese individuals including the X chromosome. Hum Genome Var. 2019;6:28.

Lee S, Seo J, Park J, Nam JY, Choi A, Ignatius JS, et al. Korean Variant Archive (KOVA): a reference database of genetic variations in the Korean population. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4287.

Tavtigian SV, Greenblatt MS, Harrison SM, Nussbaum RL, Prabhu SA, Boucher KM, et al. Modeling the ACMG/AMP variant classification guidelines as a Bayesian classification framework. Genet Med. 2018;20:1054–60.

Haldane JBS. The mean and variance of the moments of chi-squared when used as a test of homogeneity, when expectations are small. Biometrika. 1940;29:133–4.

Zhang Y, Wang F, Chen X, Liu H, Wang X, Chen J, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals the presence of DDX41 mutations in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and aplastic anemia. EJHaem. 2021;2:508–13.

ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group. Recommendation for Absence/Rarity (PM2)—Version 1.0. Approved: September 4, 2020. Available from: https://www.clinicalgenome.org/site/assets/files/5182/pm2_-_svi_recommendation_-_approved_sept2020.pdf.

Goyal T, Tu ZJ, Wang Z, Cook JR. Clinical and pathologic spectrum of DDX41-mutated hematolymphoid neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:829–38.

Huo L, Zhang Z, Zhou H, Xie J, Jiang A, Wang Q, et al. Causative germline variant p.Y259C of DDX41 recurrently identified in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2023;202:199–203.

Singhal D, Hahn CN, Feurstein S, Wee LYA, Moma L, Kutyna MM, et al. Targeted gene panels identify a high frequency of pathogenic germline variants in patients diagnosed with a hematological malignancy and at least one other independent cancer. Leukemia. 2021;35:3245–56.

Yang F, Long N, Anekpuritanang T, Bottomly D, Savage JC, Lee T, et al. Identification and prioritization of myeloid malignancy germline variants in a large cohort of adult patients with AML. Blood 2022;139:1208-21.

Lewinsohn M, Brown AL, Weinel LM, Phung C, Rafidi G, Lee MK, et al. Novel germ-line DDX41 mutations define families with a lower age of MDS/AML onset and lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2016;127:1017–23.

Tavtigian SV, Harrison SM, Boucher KM, Biesecker LG. Fitting a naturally scaled point system to the ACMG/AMP variant classification guidelines. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:1734–7.

Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, Middha S, McDonnell SK, Baheti S, et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:877–85.

Cheng J, Novati G, Pan J, Bycroft C, Zemgulyte A, Applebaum T, et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science. 2023;381:eadg7492.

Pejaver V, Byrne AB, Feng BJ, Pagel KA, Mooney SD, Karchin R, et al. Calibration of computational tools for missense variant pathogenicity classification and ClinGen recommendations for PP3/BP4 criteria. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109:2163–77.

Bergquist T, Stenton SL, Nadeau EAW, Byrne AB, Greenblatt MS, Harrison SM, et al. Calibration of additional computational tools expands ClinGen recommendation options for variant classification with PP3/BP4 criteria. Genet Med. 2025;27:101402.

Jaganathan K, Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S, McRae JF, Darbandi SF, Knowles D, Li YI, et al. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell. 2019;176:535–48 e24.

Cheloor Kovilakam S, Gu M, Dunn WG, Marando L, Barcena C, Nik-Zainal S, et al. Prevalence and significance of DDX41 gene variants in the general population. Blood. 2023;142:1185–92.

Choi EJ, Cho YU, Hur EH, Jang S, Kim N, Park HS, et al. Unique ethnic features of DDX41 mutations in patients with idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2022;107:510–8.

Schmidt RJ, Steeves M, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Benson KA, Coe BP, Conlin LK, et al. Recommendations for risk allele evidence curation, classification, and reporting from the ClinGen Low Penetrance/Risk Allele Working Group. Genet Med. 2024;26:101036.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding sources, including the Wilson Centre for Blood Cancer Genomics and the Snowdome Foundation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IST and PB designed the study. IST, SH, and SW collected data. YK developed the online curation application. RAC developed the Bayesian statistical framework. IST, SH, YK, NNM, RAC, JL, JC, KLC, LAG, LCF, and PB analyzed and interpreted data. IST wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

IST received honoraria from Pfizer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and BMS.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/111620/PMCC). Informed consent from participants was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiong, I.S., Hunter, S., Kankanige, Y. et al. Refinement of the classification of DDX41 variants through analysis of aggregated clinical datasets. Leukemia (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-026-02886-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-026-02886-6