Abstract

Handedness-selective chiral transport is an intriguing phenomenon that not only holds significant importance for fundamental research but also carries application prospects in fields such as optical communications and sensing. Currently, on-chip chiral transport devices are static, unable to modulate the output modes based on the input modes. This limits both device functionality reconfiguration and information transmission capacity. Here, we propose to use the incident polarization diversity to control the Hamiltonian evolution path, achieving polarization-dependent chiral transport. By mapping the evolution path of TE and TM polarizations onto elaborately engineered double-coupled waveguides, we experimentally demonstrate that different polarizations yield controllable modal outputs. This work combines Multiple-Input, Multiple-Output, and polarization diversity concepts with chiral transport and challenges the prevailing notion that the modal outputs are fixed to specific modes in chiral transport, thereby opening pathways for the development of on-chip reconfigurable and high-capacity handedness-selective devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The wavelength, mode, and polarization multiplexing are recognized as the most effective solutions to address the need for multi-channel parallel communications in optical interconnects, optical computing, and optical sensing. Polarization, as an intrinsic degree of freedom of light, is playing an increasingly significant role in multitasking information transmission. Developing polarization channel devices is beneficial for enhancing the control of the optical degrees of freedom1,2, expanding information transmission capacity3,4, improving transmission efficiency5, and reducing channel crosstalk6. Successful implementations include polarization-controlled directional coupling6, valley-locked beam splitters7, circular polarization-dependent chiral ring resonators2, and multifunctional spin lasers8. These polarization channel devices provide valuable methods for designing reconfigurable optical routers and optical computing processors, thereby contributing to the development of programmable optical communication and optical computing network technologies.

In a different context, exceptional points (EPs), consisting of singularities that arise in non-Hermitian systems where eigenvalues and eigenvectors coalesce, have been raising significant interest in various physical disciplines, including electronics and photonics9,10,11,12,13,14. The introduction and control of gain and loss distributions in photonic systems have enabled researchers to study the fundamentals of EPs and the associated non-Hermitian phenomena in a wide range of optical systems, including microcavities15,16,17,18, waveguides19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, gratings33,34, and photonic crystals35,36. Many intriguing phenomena, such as enhanced sensing37,38,39,40, unidirectional invisibility41,42, single-mode lasers16,43, and chiral dynamics21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, have emerged due to the unique topological features around EPs, which not only are of importance from the fundamental standpoint but also have been leading to various cutting-edge photonic technologies. Out of the many associated phenomena, dynamically encircling an EP in non-Hermitian systems, has been under intense spotlight recently due to its chiral response, where the final system state depends on the handedness of EP encircling21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Chiral transport achieved in these optical systems shows significant potential applications, such as quantum computing, asymmetric optical switches23, polarization controllers22,30, optical isolators44, and more. To overcome the challenges of low chiral conversion efficiency and large device size, which limit the practical on-chip application of chiral transport devices, researchers have proposed to use Hamiltonian hopping to enhance chiral conversion efficiency28, and have explored methods involving moving EPs and fast encircling of EPs to reduce device size31,33. Moreover, previously reported chiral transport devices are static, with each output port locked to a specific mode regardless of the input, which limits functional reconfiguration and transmission capacity improvement.

In this article, we overcome the challenge that the output modes are fixed to specific modes independent of input modes in chiral transport by introducing polarization diversity in the EP-encircling dynamics. We show that polarization diversity can be used to control the evolution direction in the Hamiltonian parameter space, thereby achieving polarization-dependent state outputs. We present experimental results by mapping the evolution trajectories of TE and TM polarizations onto elaborately engineered double-coupled waveguides, showing different output modes corresponding to different polarizations at telecommunication wavelengths. Compared to previous research, our study challenges the inherent understanding that the output mode cannot be controlled by the input but is uniquely locked to a single mode in EP-encircling chiral transport, providing opportunities for the development of on-chip reconfigurable and high-capacity chiral transmission devices.

Results

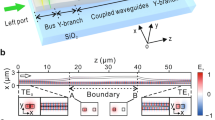

The evolution path around EPs has been conventionally realized using coupled dielectric waveguides of rectangular cross-section. In such systems, the output port of the co-designed chiral transport devices is locked to a specific mode regardless of the input incidence21,23,28,31,33. Changing the width of the rectangular waveguide influences the effective refractive indices of both TE and TM polarizations at the same time. Therefore, the associated Hamiltonian parameters undergo a co-directional evolution path for both polarizations. Here, instead we implement anti-directional evolution paths for TE and TM polarizations, achieved by introducing L-shaped waveguide cross-sections in double-coupled waveguides. We start by analyzing TE and TM modes supported by L-shaped silicon waveguides, as shown in Fig. 1a, b. It can be seen that TE and TM polarizations are distributed differently, where TE and TM polarizations are mainly distributed in the central and right regions of the waveguide, respectively. Although their effective refractive indices increase when either the top or bottom width increases, their sensitivity to the top and bottom widths differs. The TE polarization is insensitive to changes in the top width but sensitive to changes in the bottom width. Conversely, the TM polarization is sensitive to changes in the top width, but insensitive to changes in the bottom width. We are thus able to alter the top and bottom widths so that the effective refractive indices of TE and TM polarizations change in opposite directions. If an L-shaped waveguide and a rectangular waveguide are combined to form double-coupled waveguides, as shown in Fig. 1c, we can optimize the geometry such that the detuning of TE and TM polarizations change in opposite directions, resulting in polarization-controlled chiral transport. It should be noted that the detuning of TE and TM polarizations is proportional to the difference in their respective effective refractive indices. The evolution direction for the Hamiltonian parameters is determined by the detuning of double-coupled waveguides, rather than by the effective refractive index of a single waveguide. If only the width of either the top or bottom layer of the L-shaped waveguide is varied, the detuning for both TE and TM polarizations will change in the same direction, which cannot achieve the goal of polarization-controlled chiral transport. In this work, the device length for the double-coupled waveguides is chosen as 170 µm to strike a balance between satisfying the adiabatic condition and minimizing device length. More detailed optimization of the geometrical parameters of the double-coupled waveguides can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

a, b Modal field and index variations for TE and TM polarizations by changing the upper (a) and lower (b) widths of the single L-shaped waveguide. Below the modal field distributions, n denotes the modal index. The lower and upper widths of the baseline waveguide are Wb = 700 nm and Wa = 350 nm, respectively, and their width variations are ΔWa = ΔWb = 100 nm. c Dual-coupled waveguides for demonstrating polarization-controlled chiral transport. The cross-sectional parameters are marked in the left panel. The blue line with arrows in the right panel shows the evolution trajectory, where its projection onto (β/κ, γ/κ) plane is marked by the brown line. d, e β versus WLa and WLb at 1550 nm for TE (d) and TM (e) polarizations, with WR being fixed at 450 nm. The white straight lines represent the structural parameter variations from O to A−. f β as a function of the propagation distance, z. The entire silicon waveguides are covered by a 1-μm-thick SiO2 layer, with the refractive indices of Si and SiO2 being 3.478 and 1.444 at 1550 nm, respectively. The full height of the L-shaped waveguide is ha = 340 nm, and the height of the lower waveguide is hb = 220 nm. The modal field distributions in a, b are obtained by FDTD simulations

The double-coupled waveguides can be rigorously described with the evolution equation as

where the eigenfunction is expressed as \(|\psi (z)\rangle ={[{a}_{1}(z),{a}_{2}(z)]}^{T}\), a1(z) and a2(z) are the amplitudes of modes in each waveguide, and the eigenstates [1,1]T and [1,−1]T correspond to the symmetric and anti-symmetric modes, respectively. The Hamiltonian can be written as

Here, β(z), γ(z), and κ(z) represent the degree of detuning, loss rate, and coupling strength of the system, respectively. The Hamiltonian parameters (β, γ, and κ), associated with the waveguide geometry, can be theoretically retrieved based on coupled mode theory45 and the Beer–Lambert–Bouguer law46. The two eigenvalues are \({E}_{1,2}={i}{\gamma} /{2} {\pm} \sqrt{{\kappa}^{2}+{({\beta} +{i}{\gamma} /{2})}^{2}}\) and the associated eigenvectors \(|{X}_{1,2}\rangle ={[\sqrt{1{\pm}M},{\pm} \sqrt{1-({\pm} M)}]}^{T}/\sqrt{2}\), where \(M=(\beta +i\gamma /2)/\sqrt{{\kappa }^{2}+{(\beta +i\gamma /2)}^{2}}\), indicating that the system has an EP at (β/κ, γ/κ) = (0,2). Previous studies have shown that when the dynamic Hamiltonian trajectories surround the EP, the different losses experienced by different eigenstates lead to the generation of nonadiabatic transitions (NAT), which makes the output modes depend on the handedness of EP encircling10,21,23,28,33. In Section I, the width of the right rectangular waveguide is kept constant, and the top and bottom widths of the left L-shaped waveguide reduces and increases along the z direction. In this situation, the detuning of TE and TM polarizations between the two waveguides is negative and positive, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1d–f. In Section II, the positions of the rectangular and L-shaped waveguides are swapped compared to Section I. Therefore, the detuning of TE and TM polarizations are opposite to those in Section I, respectively. To avoid path-dependent loss in encircling EPs, we have employed the strategy of “Hamiltonian hopping” between convergent eigenstates at Hamiltonian boundaries28, i.e., points A−, {B}, and A+, as indicated in Fig. 1c. A− (A+) can be reached by increasing the gap distance, d, which effectively makes κ(z) → 0. It should be noted that TE and TM polarizations take opposite values at A− (A+) points, due to their opposite detuning. A large loss rate γ at {B} can be implemented using a semi-infinite slab waveguide to replace the first waveguide. Bend waveguides are used to connect the right waveguide with the slab waveguide. Once the guided waves reach the slab waveguide through the bend, light is not reflected back, i.e., γ/κ → ∞ as required at {B}. It should be emphasized that in previous studies using the Hamiltonian hopping strategy with coupled dielectric waveguides of rectangular cross-section, chiral mode switching was achieved by Hamiltonian transitions between convergent eigenstates at Hamiltonian boundaries during EP encircling28. However, in these studies, the evolution directions for TE and TM polarizations were the same, preventing the realization of polarization-dependent chiral switching. In contrast, the present work employs an intricately designed L-shaped waveguide structure. This design leverages the convergent eigenstates at Hamiltonian boundaries, enabling Hamiltonian transitions between these states during EP encircling, thereby achieving chiral mode switching. Additionally, it facilitates polarization-dependent chiral switching, as TE and TM polarizations evolve in opposite directions (Fig. 1c). In contrast, previous studies on chiral mode switching using enclosed trajectories encircling EPs were unable to implement reverse evolution directions for TE and TM polarizations, which prevented polarization-dependent chiral switching23,26,31,33. More details regarding the dependence of γ and κ on the geometry of the double-coupled waveguides can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

To validate the functionality of polarization-controlled chiral transport, we conducted full-wave simulations using the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method to simulate the field intensity distributions of the double-coupled waveguides (Fig. 2). The output mode is not locked to a specific mode, but it is dependent on the incident polarization. For the left (right) port input with TE0 and TM0 modes, the output mode is TE1 (TE0) and TM0 (TM1) modes, respectively. When the TE0 mode is input from the left port, most of the light energy resides in the left waveguide between A− and A+, where the dominant eigenstate is [0,1]T (Fig. 2a). However, when TM0 mode is input, most of the light energy is concentrated in the right waveguide at A− and eventually dissipates as it travels through the bent waveguide to the slab waveguide, as shown in Fig. 2b. When the TE0 (TM0) mode is input from the right port, the evolution process is similar to the one when TM0 (TE0) mode is input from the left port, and the output mode will be TE0 (TM1) mode (Fig. 2c, d). It should be noted that the output mode is locked to TE1 (TM0) for the left port input and to TE0 (TM1) for the right port input, regardless of whether the input is a symmetric or antisymmetric mode. Simulation results with anti-symmetric mode incidence can be found in Supplementary Note 2. Overall, the simulation results demonstrate polarization-controlled chiral transmission for the double-coupled waveguides.

a, c Field distributions of Ex, when TE0 mode inputs from the left (a) and right (c) ports, respectively. b, d Field distributions of Ey, when TM0 mode inputs from the left (b) and right (d) ports, respectively. The simulated field distributions in the double-coupled waveguides at z = 0, 70, 100, and 170 µm are obtained by FDTD simulations

To understand the physics behind the intriguing polarization-controlled chiral response, the light transmission in the double-coupled waveguides can be rigorously described by Eq. (1). Assuming that H(z) remains constant over the distance interval [z0,z], the final state can be written as

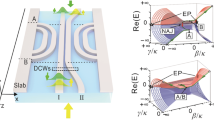

The initial state is \(|\psi ({z}_{0})\rangle ={c}_{1}({z}_{0}){X}_{1}+{c}_{2}({z}_{0}){X}_{2}\) at z0. Equation (3) indicates that the real and imaginary parts of the eigenvalues affect the phase and magnitude, respectively. We can thus present the dynamic Hamiltonian trajectories in the Riemann surfaces formed by the energy spectra of Hamiltonian for TE and TM polarizations, as schematically shown in Fig. 3. The dynamic trajectories are opposite for TE and TM polarizations when they are injected into the same port, due to the opposite sign of the detuning β of TE and TM polarizations.

The evolution trajectories in the Riemann surfaces are formed by the real part Re(E) and imaginary part Im(E) of the energy spectra of H, when the symmetrical mode is input from the left (a–d) and right (e–h) ports, respectively. The dashed meshes represent the Hamiltonian parameters extended to infinity. The blue and red solid lines represent the parameter space boundary, associated with the eigenstates as [0,1]T and [1,0]T, respectively. The dashed lines refer to Hamiltonian hopping among A−, {B} and A+

For symmetrical modes injected from the left port, the associated state [1,1]T at the starting point (β/κ, γ/κ) = (0, 0) is situated in the upper half of the Riemann surface (Fig. 3a–d). When a TE0 mode is injected and evolves clockwise from (0, 0) to A−, X1 is dominant, and it suffers from low loss as the imaginary part of E1 is zero. The Hamiltonian ultimately returns to (0, 0) after it undergoes successive hopping between A−, {B} and A+. Throughout the entire process, X1 is always dominant, resulting in the output state X1 = [1,−1]T on the lower half of the Riemann surface, corresponding to the TE1 mode (Fig. 3a, b). In contrast to the TE0 mode, the Hamiltonian evolves oppositely when the TM0 mode is injected. During the evolution process from (0, 0) to A−, the Hamiltonian evolves anticlockwise, in which X2 is dominant, and X1 is slightly excited since the adiabatic condition cannot be strictly satisfied. During the hopping between A−, {B}, and A+, the dominant state X2 incurs significant loss and eventually is dissipated, while X1 remains lossless and becomes the dominant state, i.e., a NAT occurs. The output state returns to X1 = [1,1]T at (0, 0) on the upper half of the Riemann surface, corresponding to the TM0 mode (Fig. 3c, d).

For symmetrical modes injected from the right port, the initial state [1,1]T is also situated in the upper half of the Riemann surface (Fig. 3e–h). For TE0 injection, the dominant eigenstate transitions from X2 to X1, when the system experiences NAT. The system state becomes [1,1]T at the terminal point (0, 0), corresponding to TE0 mode, as it evolves along the upper surface of the Riemann surface (Fig. 3e, f). For TM0 injection, X1 is consistently dominant, and the system state finally outputs as [1,−1]T at (0, 0), corresponding to TM1 mode (Fig. 3g, h). The dynamics process for the injection of symmetrical modes of different polarizations further validates the polarization-controlled chiral transport of the double-coupled waveguides. It should be noted that the output modes are locked with the same polarization incidence, regardless of the mode order. More details regarding the dynamics process can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

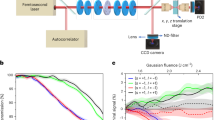

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images for the double-coupled silicon waveguides in one of the fabricated samples are shown in Fig. 4a. The zoomed-in images on the left and right planes represent the regions bounded by the black rectangles (see Supplementary Note 4 for the fabrication details and transmission measurement scheme). These images clearly indicate that the L-shaped and rectangular waveguides are reversed in the regions near the left and right ports. The simulated and measured transmission efficiencies for TE0 and TM0 input around 1550 nm are shown in Fig. 4b–e. Tmn (T'mn) represents the transmission efficiency of TEm or TMm mode that outputs from the right (left) port when TEn or TMn mode inputs from the left (right) port. When TE0 (TM0) mode is injected from the left port, the extracted experimental efficiency deviation at 1550 nm is T10–T00 ≈ 12 dB (T00–T10 ≈ 13 dB), i.e., T10 ≫ T00 (T00 ≫ T10), indicating that TE1 (TM0) mode dominates in the output. In contrast, when TE0 (TM0) mode is injected from the right port, we have T'00–T'10 ≈ 28 dB (T'10–T'00 ≈ 22 dB), i.e., T'00 ≫ T'10 (T'10 ≫ T'00), indicating that the output mode is dominated by TE0 (TM1) mode. It should be emphasized that mode crosstalk in coupled waveguides cannot be completely avoided, as the adiabaticity condition cannot be strictly fulfilled23. From a device performance perspective, increasing the device length can help reduce crosstalk, but this also increases fabrication complexity and device size, which may hinder high-density photonic integration. We have demonstrated that mode crosstalk can be further minimized by doubling the device length (see Fig. S6 in Supplementary Note 3). It is important to note that the use of Hamiltonian hopping does not offer a significant advantage over previous strategies in terms of reducing mode crosstalk. In fact, the crosstalk observed in our device is comparable to that in devices that do not use Hamiltonian hopping21,23,24,28,31. These measurement results are consistent with the polarization-controlled chiral transport as has been predicted by the aforementioned theory and simulation. The experimental results generally match the simulation results, with some deviations mainly attributed to fabrication errors in the sample and testing inaccuracies due to noise, especially when the transmission efficiency is very low. Specifically, the testing errors primarily arise from alignment errors and the limitation of the single writing field area during the EBL fabrication process of the L-shaped waveguides, as well as the impact of dark current noise in the spectrometer on low transmission efficiency.

If further developed to guide different output polarizations along different waveguides, the polarization-controlled chiral converter can be extended to construct a chiral polarization router. This holds promise for applications in quantum walk systems to generate spin-correlated quantum states that are insensitive to input modes, indicating significant potential in quantum information processing47. For example, polarization-switchable logic gates can be realized by using polarization-controlled chiral converters integrated with Y-branch waveguides. More sophisticated polarization-switchable logic gate functions are expected to emerge by combining the polarization-controlled chiral converters with other complex logic gates48. However, some logic gate designs are limited by strong polarization dependence. Therefore, to advance the development of sophisticated polarization-switchable logic gates using polarization-controlled chiral converters, it is crucial to address the polarization-dependence issue present in existing optical logic gates. Moreover, selectively introducing gain or loss in polarizations might be beneficial to achieve on-chip polarization-controlled output from lasers49. Compared to previous studies on chiral transport based on EP encircling23,24,25,26,27,28,29, we have also introduced the degree of polarization freedom to increase the number of photonic transmission channels, which helps enhance multiplexing dimensions and expand communication capacity. Simulation results indicate that even with a ±50 nm alignment error, our device can maintain crosstalk below −10 dB, exhibiting favorable polarization-dependent asymmetric transmission effects. The device exhibits high fabrication robustness, facilitating its future practical fabrication and applications. The detailed simulation results are provided in Supplementary Note 5. In previous studies on chiral transmission, the chiral transmission efficiency is defined as the maximum transmittance across all input states and encircling directions31. The transmission efficiency of the proposed polarization-controlled chiral devices approaches unity, owing to the use of Hamiltonian hopping, which avoids path-dependent losses. Most studies rely on the strategy of encircling EPs to achieve chiral transmission, but this approach suffers from path-dependent losses along the entire evolution path, leading to a low chiral transmission efficiency. The maximum reported chiral transmission efficiency is below 0.4621,23,24,33. Other strategies involve slow evolution without encircling near EPs, which not only suffer from path-dependent losses along the entire evolution path but also induce additional NAT for both evolution directions50,51. As a result, the chiral transmission efficiencies in these cases are even lower than those achieved using the strategy of encircling near EPs.

It should be emphasized that, low transmission efficiency in the NAT-associated directions can limit the degree of freedom in multiplexing. Although NAT can, in principle, be achieved by applying either loss or gain, existing experiments have predominantly relied solely on loss to implement NAT in passive photonic devices21,23,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. This preference stems from the fact that loss is easier to implement experimentally than gain. In previous studies on chiral transmission based on double-coupled waveguides without considering polarization multiplexing, only one branch of high transmission was achieved, corresponding to one single degree of freedom for multiplexing. In contrast, the proposed polarization-controlled chiral transport devices can utilize two branches of high transmission for polarization multiplexing, enabling polarization multiplexing and corresponding to two degrees of freedom. To further enhance the degrees of multiplexing, one potential approach is to implement multiple groups of chiral mode switching or to replace the current passive devices with active ones to improve transmission efficiency. While we have demonstrated the implementation of polarization diversity using a second-order system with chiral transport, polarization diversity in third-order or higher-order systems could be achieved by using three or more L-shaped coupled waveguides in principle. As an example, we have numerically demonstrated chiral transport for polarization diversity in a third-order Hamiltonian system with three-coupled L-shaped waveguides. Further details can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have reported an on-chip polarization-controlled reconfigurable chiral transport device. We have shown that, in a double-coupled waveguide system, the Hamiltonian can be controlled to evolve around EPs in opposite directions for TE and TM polarizations, achieving polarization-controllable chiral transmission. Unlike previous works where output modes were uniquely determined by the incident direction, our approach allows output modes to be controlled by the incident polarization states. The silicon photonic experiments have verified the polarization-controlled chiral transmission effect. Our approach is general and can be extended to chiral transport in other physical fields such as acoustics, electronics, and condensed matter physics. From an application perspective, this novel device can function as a routing unit for high-performance optical communication and optical computing networks, effectively increasing optical information transmission capacity and enhancing optical computing power.

Materials and methods

Fabrications

The fabrication of the devices is combined with three-step electron-beam lithography (EBL), inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching, electron-beam evaporation (EBE), and plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). The first step, EBL and EBE, is aimed at forming the Au marks on an SOI wafer for alignment. The second step, EBL and ICP, is used to define the partially etched layer of the L-shaped silicon waveguides. The fully-etched layer of the L-shaped silicon waveguides is fabricated by the third-step EBL and ICP. Finally, the PECVD is applied to deposit a 1-μm-thick SiO2 cladding layer to cover the entire device.

Measurements

An amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) source (OVLINK ASE-CL-20-B) provides the near-infrared light, and its polarization is adjusted by a polarizing beam splitter (PBS) and a polarization controller. The grating coupler is used to couple the light from the fiber into TE0 mode or decouple the TE0 mode out of the silicon waveguide back into the fiber. The decoupled light will be collected by the optical power meter (PMSII-A) and a spectrometer (YOKOGAWA AQ6370C). See more details on the measurements in Supplementary Note 4.

Data availability

All data required to interpret the results in this paper are provided within the main text and supplementary material. Any additional data in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. The code that supports the plots within this paper is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Hu, G. W. et al. Coherent steering of nonlinear chiral valley photons with a synthetic Au–WS2 metasurface. Nat. Photonics 13, 467–472 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Chirality-dependent unidirectional routing of WS2 valley photons in a nanocircuit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1178–1182 (2022).

Zhang, X. G. et al. Polarization-controlled dual-programmable metasurfaces. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903382 (2020).

Ma, Q. et al. Editing arbitrarily linear polarizations using programmable metasurface. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 021003 (2020).

Ding, F., Tang, S. W. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Recent advances in polarization-encoded optical metasurfaces. Adv. Photonics Res. 2, 2000173 (2021).

Lin, J. et al. Polarization-controlled tunable directional coupling of surface Plasmon polaritons. Science 340, 331–334 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Topologically protected valley-dependent quantum photonic circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 230503 (2021).

Duan, X. Y. et al. Valley-addressable monolayer lasing through spin-controlled Berry phase photonic cavities. Science 381, 1429–1432 (2023).

Klaiman, S., Günther, U. & Moiseyev, N. Visualization of branch points in PT-symmetric waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 080402 (2008).

Rüter, C. E. et al. Observation of parity–time symmetry in optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 192–195 (2010).

Chen, Z. G. & Segev, M. Highlighting photonics: looking into the next decade. eLight 1, 2 (2021).

Kononchuk, R. et al. Exceptional-point-based accelerometers with enhanced signal-to-noise ratio. Nature 607, 697–702 (2022).

Suntharalingam, A. et al. Noise resilient exceptional-point voltmeters enabled by oscillation quenching phenomena. Nat. Commun. 14, 5515 (2023).

Li, A. D. et al. Exceptional points and non-Hermitian photonics at the nanoscale. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 706–720 (2023).

Peng, B. et al. Parity–time-symmetric whispering-gallery microcavities. Nat. Phys. 10, 394–398 (2014).

Hodaei, H. et al. Parity-time–symmetric microring lasers. Science 346, 975–978 (2014).

Brandstetter, M. et al. Reversing the pump dependence of a laser at an exceptional point. Nat. Commun. 5, 4034 (2014).

Lee, H. et al. Chiral exceptional point and coherent suppression of backscattering in silicon microring with low loss Mie scatterer. eLight 3, 20 (2023).

Guo, A. et al. Observation of PT-symmetry breaking in complex optical potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 093902 (2009).

Graefe, E. M., Mailybaev, A. A. & Moiseyev, N. Breakdown of adiabatic transfer of light in waveguides in the presence of absorption. Phys. Rev. A 88, 033842 (2013).

Doppler, J. et al. Dynamically encircling an exceptional point for asymmetric mode switching. Nature 537, 76–79 (2016).

Hassan, A. U. et al. Dynamically encircling exceptional points: exact evolution and polarization state conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 093002 (2017).

Yoon, J. W. et al. Time-asymmetric loop around an exceptional point over the full optical communications band. Nature 562, 86–90 (2018).

Zhang, X. L. et al. Dynamically encircling exceptional points: in situ control of encircling loops and the role of the starting point. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021066 (2018).

Zhang, X. L. et al. Distinct outcomes by dynamically encircling an exceptional point along homotopic loops. Phys. Rev. A 99, 063831 (2019).

Zhang, X. L., Jiang, T. S. & Chan, C. T. Dynamically encircling an exceptional point in anti-parity-time symmetric systems: asymmetric mode switching for symmetry-broken modes. Light 8, 88 (2019).

Zhang, X. L. & Chan, C. T. Dynamically encircling exceptional points in a three-mode waveguide system. Commun. Phys. 2, 63 (2019).

Li, A. D. et al. Hamiltonian hopping for efficient chiral mode switching in encircling exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 187403 (2020).

Yu, F. et al. General rules governing the dynamical encircling of an arbitrary number of exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 253901 (2021).

Li, A. D. et al. Riemann-encircling exceptional points for efficient asymmetric polarization-locked devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 127401 (2022).

Shu, X. Q. et al. Fast encirclement of an exceptional point for highly efficient and compact chiral mode converters. Nat. Commun. 13, 2123 (2022).

Shu, X. Q. et al. Chiral transmission by an open evolution trajectory in a non-Hermitian system. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 65 (2024).

Liu, Q. J. et al. Efficient mode transfer on a compact silicon chip by encircling moving exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 153903 (2020).

Liu, Q. J. et al. On-chip experiment for chiral mode transfer without enclosing an exceptional point. Phys. Rev. A 103, 023531 (2021).

Kim, K. H. et al. Direct observation of exceptional points in coupled photonic-crystal lasers with asymmetric optical gains. Nat. Commun. 7, 13893 (2016).

Weimann, S. et al. Topologically protected bound states in photonic parity–time-symmetric crystals. Nat. Mater. 16, 433–438 (2017).

Hodaei, H. et al. Enhanced sensitivity at higher-order exceptional points. Nature 548, 187–191 (2017).

Chen, W. J. et al. Exceptional points enhance sensing in an optical microcavity. Nature 548, 192–196 (2017).

Hokmabadi, M. P. et al. Non-hermitian ring laser gyroscopes with enhanced sagnac sensitivity. Nature 576, 70–74 (2019).

Park, J. H. et al. Symmetry-breaking-induced plasmonic exceptional points and nanoscale sensing. Nat. Phys. 16, 462–468 (2020).

Lin, Z. N. et al. Unidirectional invisibility induced by PT-symmetric periodic structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 213901 (2011).

Feng, L. et al. Experimental demonstration of a unidirectional reflectionless parity-time metamaterial at optical frequencies. Nat. Mater. 12, 108–113 (2013).

Feng, L. et al. Single-mode laser by parity-time symmetry breaking. Science 346, 972–975 (2014).

Laha, A. et al. Exceptional point and toward mode-selective optical isolation. ACS Photonics 7, 967–974 (2020).

Chuang, S. L. A coupled mode formulation by reciprocity and a variational principle. J. Lightwave Technol. 5, 5–15 (1987).

Abitan, H., Bohr, H. & Buchhave, P. Correction to the Beer-Lambert-Bouguer law for optical absorption. Appl. Opt. 47, 5354–5357 (2008).

Tang, Z., Chen, T. & Zhang, X. D. Highly efficient transfer of quantum state and robust generation of entanglement state around exceptional lines. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2300794 (2024).

Liao, K. et al. All-optical computing based on convolutional neural networks. Opto-Electron. Adv. 4, 200060 (2021).

Schumer, A. et al. Topological modes in a laser cavity through exceptional state transfer. Science 375, 884–888 (2022).

Hassan, A. U. et al. Chiral state conversion without encircling an exceptional point. Phys. Rev. A 96, 052129 (2017).

Nasari, H. et al. Observation of chiral state transfer without encircling an exceptional point. Nature 605, 256–261 (2022).

Acknowledgements

H.Z., L.C., and J.W. were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12474382), National Key Research and Development Project of China (Grant No. 2024YFA1209302), Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (Grant No. JCYJ20220530161010023), and Key Laboratory of High-Temperature Electromagnetic Materials and Structure of MOE, Wuhan University of Science and Technology (Grant No. KB202501). A.A. was supported by the Simons Foundation. We thank the Center of Optoelectronic Micro & Nano Fabrication and Characterizing Facility of WNLO for the support in SEM measurement.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12474382), National Key Research and Development Project of China (Grant No. 2024YFA1209302), Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (Grant No. JCYJ20220530161010023), and Key Laboratory of High-Temperature Electromagnetic Materials and Structure of MOE, Wuhan University of Science and Technology (Grant No. KB202501).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. and L.C. conceived the idea and initiated the work. L.C. guided the project. H.Z. developed the theoretical framework, performed the numerical simulations and conducted the experiments. J.W. and A.A. discussed the results. H.Z., A.A., and L.C. wrote the paper and all authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, H., Wang, J., Alù, A. et al. Polarization-controlled chiral transport. Light Sci Appl 14, 77 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-01762-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-01762-9

This article is cited by

-

Ultra-broadband and Wide-angle Metamaterial Absorber Based on Vertical Three-square Patches Structure Gallium Nitride for Terahertz Wave

Journal of Electronic Materials (2025)