Abstract

The possibility of freely manipulating flow in accordance with humans will remain indispensable for breakthroughs in fields such as microfluidics, nanoengineering, and biomedicines, as well as for realizing zero-drag hydrodynamics, which is essential for alleviating the global energy crisis. However, persistent challenges arise from the D’Alembert paradox and the unresolved Navier-Stokes solutions, known as the Millennium Problem. These obstacles also complicate the development of hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks across diverse Reynolds numbers. Our research introduces a paradigm for such cloaks, relying exclusively on isotropic and homogeneous viscosity. Through experimental and numerical validations, our cloaks exhibit zero-drag properties, effectively resolving the D’Alembert paradox in viscous potential flows. Moreover, they possess the capability to activate or deactivate hydrodynamic concealment at will. Our analysis emphasizes the critical role of vorticity manipulation in realizing cloaking effects and drag-reduction technology. Therefore, controlling vorticity emerges as a pivotal aspect for future active hydrodynamic zero-drag cloak designs. In conclusion, our study challenges the prevailing belief in the impossibility of zero drag, offering valuable insights into invisibility characteristics in fluid mechanics with implications for microfluidics, biofluidics demanding the drug release or biomolecules transportation accurately and timely, and hypervelocity technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invisibility characteristics, which ensure interference-free interactions between the intrusive objects and peripheral environments, are of great importance in modern microfluidics and nanoengineering, such as biomolecules transported in microfluidic chips or biomedicines manipulation, including accurate drug release1,2. Likewise, invisibility contributes to achieving hydrodynamic zero-drag performance by eliminating mutual interactions, playing a vital role in addressing the escalating global energy crisis that arises from the ever-increasing demand for energy worldwide. For energy crisis alleviation, one of the critical challenges lies in overcoming drag during the motion of objects. Consequently, the urgency to advance drag-reduction technology3,4,5, particularly in marine transportation, the automotive industry, aviation, military, pipeline systems, and biofluidic and microfluidic communities, has become imminent. In conventional methods, researchers primarily focus on superhydrophobic surfaces6,7, bioinspired texture surfaces8,9, fluid-infused surfaces10,11, and others. However, these methods do not allow the resistance against the motion of an object to be completely eliminated.

Inspired by electromagnetic cloaks12,13 that can hide the objects electromagnetically by regulating the path of the electromagnetic wave, hydrodynamic cloaks14,15,16,17,18 and thermal cloaks19,20,21,22,23 have been developed. These hydrodynamic cloaks are capable of reducing the drag on objects moving in a fluid. Besides, they can redirect fluid flows while maintaining the original distributions of the external hydrodynamic fields where blunt-body flows occur. Therefore, they have been investigated profoundly, and have attracted extensive attention.

The concept of hydrodynamic cloaks was first proposed to study porous media14,15 for creeping flows and laminar flows on the basis of Darcy’s law and transformation theory12,13, which regulates the fluid flows through the manipulations of permeability. Subsequent experimental studies24,25,26 are conducted successfully to validate the effectiveness of transformation media under the flow control and have provided valuable insights into the practical realization of hydrodynamic cloaks at the experimental level.

For the purpose of developing the transformation theory in hydrodynamics beyond porous media, transformation hydrodynamics16 is first proposed by manipulating the fluid viscosity in creeping flows and further extended to laminar flows27. Hereafter, a multitude of hydrodynamic meta-devices based on transformation hydrodynamics, such as hydrodynamic concentrators28 and hydrodynamic rotators29 have emerged. Additionally, the proposal of arbitrary space transformation theory30,31,32 has further expanded the achievement of hydrodynamic cloaks and enhanced our comprehension of space transformation. Nonetheless, the inhomogeneous and anisotropic parameters of these cloaks proceed to challenge experimental fabrications.

To address these issues, Tay et al. have attained a metamaterial-free hydrodynamic cloak by virtue of the scattering cancellation method33. Furthermore, innovative methods such as convection-diffusion-balance theory34, electro-osmosis method35, deep-reinforcement-learning approach36, and meta-hydrodynamics theory37 have been proposed. More comprehensive studies regarding hydrodynamic cloaks can be found in the review38,39,40,41. However, previous studies have seldom explored the drag-reduction properties of hydrodynamic cloaks, and even fewer have considered the potential for achieving zero-drag performance or the underlying mechanisms driving this phenomenon.

To overcome these challenges, here we propose a paradigm to fabricate hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks with the analytical solution. By verifying our hydrodynamic cloaks experimentally and numerically, we find that the elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks exhibit zero-drag characteristics over a large-Re range. Furthermore, these characteristics of the cloak illustrate that we resolve the D’Alembert paradox42,43 in viscous potential flows, which had been proven to exist only in the ideal fluids. Moreover, the hydrodynamic cloaks can switch on and off at will, which significantly enhances the accurate flow manipulations. Finally, we discover that the vorticity transport explicitly determines the drag-reduction and cloaking effects of hydrodynamic cloaks, and hence propose that the vorticity controlling probably becomes a promising perspective to achieve hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks under higher Re’s.

Theoretical design

According to Newton’s Third Law, free interferences imply zero drag on the objects in motion through a fluid. For example, precise biomolecule transportation and stable drug release (Fig. 1a) can be ensured by eliminating mutual interferences (equivalent to zero drag) between transported objects and microfluidic chips or biological systems, thus lowering the energy input, minimizing the rejection rates and achieving sustained release effect. Additionally, the ability to switch the hydrodynamic cloak on and off will enable targeted drug delivery in biological systems. Similarly, in the case of nanoengineering research (Fig. 1a), such as intracellular measurement1, free interferences provided by hydrodynamic metamaterials promise more accurate manipulation just parallel to electromagnetic metamaterials2. Therefore, it is imperative to design hydrodynamic cloaks capable of entirely mitigating interferences between moving objects and the surrounding fluids, as well as achieving zero-drag characteristics.

a Potential application of hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks upon mutual hydrodynamic interactions between intrusive objects and peripheral environments are eliminated. b Two-dimensional model of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks, where ξ1 and ξ2 indicate the geometric parameters of the object (region I) and cloaks (region II), and both of them are horizontally located, steadily immersed in a freestream (region III). c Drag of the cloak wrapped around the object (red line), drag of the object existence only (black line), and drag-reduction effects (cyan line) vary with various Re’s. Hydrodynamic cloaks that can be switched on and off at will are seen in the supplemental video

The governing equations of continuity and momentum transport for steady-state incompressible flows without the influence of body forces can be expressed as

where u and p are velocity vector and pressure, respectively. Symbols ρ and μ denote density and dynamic viscosity, respectively.

To solve the analytical solution of the elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks (Fig. 1b), the solution of Navier-Stokes equations believed one of the Millennium Problems has to be settled first, which in turn challenges the design of hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks44,45. Therefore, simplifications of Navier-Stokes equations become necessary. It is commonly known that the vorticity aggravates the instability of fluid flows, namely, elimination of vorticity emerges as one promising perspective for accurate flow control. Hence, we focus on viscous potential flows considered as irrotational flows, in which Navier-Stokes equations can be transformed to Laplace-like equations. Ulteriorly, the analytical solutions of Navier-Stokes equations and hydrodynamic cloaks can be obtained using variables separation method46 (see Supplemental Material S.1). Accordingly, the dynamic viscosity of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks can be expressed as

where μb and μc denote the dynamic viscosity in the background (region III in Fig. 1b) and hydrodynamic cloak (region II in Fig. 1b).

Apparently, dynamic viscosity merely relates to geometry parameters and dynamic viscosity of the background, which indicates constant. It is worth mentioning that although our cloaks are predicated on viscous potential flows, they can hold firmly in any real fluid flow insofar as vorticity is eliminated and featuring irrationality patterns. In summary, the paradigm for homogeneous and isotropic hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks is established, and the analytical solution for elliptical hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks is obtained as well.

Results and discussion

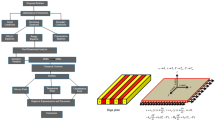

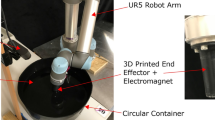

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed paradigm, experiments and numerical analysis are conducted. For hydrodynamic cloak manipulations, numerous flow-control technologies abound, such as bionics47,48, optofluidics49,50, magnetohydrodynamics51,52, electroosmotic flows53,54, thermo-hydrodynamics55,56, and among others. Here, we choose the easy-to-implement thermostatically controlled method (belonging to thermo-hydrodynamics), which matches the viscosity manipulations more accurately (see Supplemental Material S.2).

To construct irrotational flows required by our paradigm, a classic viscous potential flow named Hele-Shaw flows57,58, that exhibit irrotationality, is involved to validate the elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks experimentally and numerically. Computational simulations are conducted using commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics. The geometrical sizes of computational model are Hheight × Wwidth × Ddepth = 600 mm × 300 mm × 50 µm that patterns Hele-Shaw flows57,58. The confocal length of both elliptical objects with ξ1 = 0.45 and hydrodynamic cloaks with ξ2 = 1 is f = 50 mm. Setting water as a working fluid whose density, dynamic viscosity at room temperature is 103 kg/m3 and 10−3 Pa · s, respectively. For simplicity, we replace the elliptical object with an impermeable and nonslip wall at ξ = ξ1 in the computational domain during numerical simulations. To ensure the robustness and accuracy of the simulation, the final number of degrees of freedom (DOFs) was 1,061,832 after laborious simulation exercises, and a multifrontal massively parallel sparse direct solver (MUMPS) was utilized.

As mentioned above, free interferences promise the zero-drag characteristics, hence the drag-reduction effect are exhibited first to examine the validity of the proposed cloaks. To evaluate the drag-reduction performance of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks, we calculate the drag experienced by the objects both with and without the elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks. Herein, drag (Fig. 1c) is calculated based on the formula59 that \(\int{\int}_{s}\{\mu [(\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial x})+2\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}+(\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}+\frac{\partial w}{\partial x})]+{p}_{x}\}dS\), where μ is the dynamic viscosity, px denotes the pressure component of the x direction; u, v and w represent the velocity components along the x, y, and z direction respectively. S signifies the surfaces of the object at ξ = ξ1 for the object-existed case, and of the cloaks at ξ = ξ2 for the cloak case in consideration of the fact that the object and hydrodynamic cloaks should be treated as a whole entity. Additionally, the drag-reduction effect of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks is calculated by the formula \((1-\frac{{F}_{c}}{{F}_{o}})\times 100 \%\), where Fc (cloak case) and Fo (object-existed case) denote the drag that the objects bear in two cases.

For clarity, we define the object-existed case as only the object exists in the flow field, and the cloak case denotes elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks applied on the object-existed case. Considering the flow channel itself generates flow resistances, the background case, defined as pure background flows without objects serves as the reference point. Apparently, the drag for the object-existed case increases approximately 46–80 times (0.486 N–9.722 N) as Re increases from 50 to 1000 (Fig. 1c black line). In contrast, the drag of the cloak case (Fig. 1c red line) tends to be zero (0.006 N–0.211 N), where Re ranges from 50 to 1000. This is because there does exist vorticity near the nonslip walls in Hele-Shaw flows (quasi-irrotational flows), which directly affects the near-perfect cloaking effect (see Supplemental Material S.1) based on irrotational flows. Namely, our paradigm is capable of realizing zero-drag characteristics, as well as the resolution of the D’Alembert paradox in viscous potential flows as long as vorticities are eliminated or errors are ignored. The drag for the cloak case increases inconsiderably between Re’s of 1000 to 3000, and notably, the corresponding drag-reduction effect exceeds 96% (Fig. 1c cyan line) even when Re reaches 3000. The above demonstrates the giant drag-reduction effect that the proposed elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks hold. Indeed, the zero-drag characteristics of the hydrodynamic cloaks do resolve the D’Alembert paradox in viscous potential flows, which has been doubted for a long time. These findings challenge and reframe our conventional comprehension of hydrodynamics regarding the impossibility of zero drag, and present exciting possibilities for drag-reduction technology.

The foregoing observations effectively illustrate zero-drag characteristics of the proposed cloaks, signifying the attainment of the unimpeded interactions (cloaking effect in Fig. 2) between moving objects and the surrounding fluids, as shown in Fig. 2. Generally, the results of experiments [Fig. 2a–c] and simulations [Fig. 2d–f] align well with each other, indicating the validity and correctness of our simulation processes. Unambiguously, it can be observed that the streamlines outside of the cloaked area (regions I and II in Fig. 1b) in the cloak case behave straightly and horizontally (Fig. 2c, f) compared with object-existed case (Fig. 2b, e), and the general flow fields outward the cloaked regions (regions I and II in Fig. 1b) exactly act as that of the background case (Fig. 2a, d). In brief, elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks are capable of restoring the disturbances (Fig. 2b, e) generated by the presence of objects in background flows. Accordingly, the object appears invisible from a hydrodynamic standpoint. Furthermore, it confirms the effectiveness of the proposed thermostatically controlled method in designing hydrodynamic cloaks, as well as the validity of the proposed paradigm.

Furthermore, the velocity differences (Re = 3000) calculated by the cloak case subtracts from that of the background case displayed in Fig. 3a to demonstrate the cloaking effect quantitatively. Overall, the differences verge on zero outside the cloaked area (regions I and II in Fig. 1b). To further quantitatively verify the cloaking effects of hydrodynamic cloaks, the velocity distributions versus y/b2 (b2 is the minor axis of the cloak) at \(x=\frac{-1}{4}W,x=\frac{-3}{20}W\) and x = 0 are exhibited (Fig. 3b). Apparently, the distributions outside the cloaked regions manifest uniform in conformity with that in the background case (black dashed lines). These ulteriorly confirm the near-perfect cloaking effect of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks and verify the free interferences between the objects and external flows, which firmly supports the drag-free characteristics.

a Velocity differences distributions between the background case and cloak case. b Velocity distributions of cloak case versus y/b2 (b2 is the minor axis of the cloak) at \(x=\frac{-1}{4}W,x=\frac{-3}{20}W\) and x = 0. The black dashed line refers to the velocity distributions of the background case

Despite the near-perfect cloaking effect of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks, we do find that the velocity differences (Fig. 3a) in region III (Fig. 1b), especially the area near the cloaked regions, fluctuate around zero, and drag in cloak case vary under higher Re’s (Fig. 1c). Therefore, to investigate the mechanism behind these phenomena, the velocity (Fig. 4a) and vorticity (Fig. 4b) distributions of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks at a Re of 3000 are analyzed. At Re = 3000, a slight curvature of the streamlines and isobars near the surface of the cloak can be observed (Fig. 4a). This phenomenon indicates a degradation of the cloaking effect with the simultaneous increase of the drag in the cloak case, where the drag-reduction effect is slightly weakened (96.12%). The key to understanding this phenomenon lies in the vorticity increments in viscous potential flows when the objects exist. Although viscous potential flows behave like ideal flows, the introduction of nonslip walls of the objects, and the velocity differences between the cloaking layer (region II in Fig. 1b) and background (region III in Fig. 1b) do induce the vorticity (Fig. 4b) with the increase of Re, which affects the cloaking effect eventually.

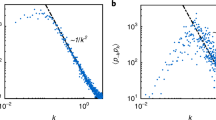

a Velocity distributions at Re = 3000 superimposed with streamlines (black color) and isobars (white color). b Vorticity distributions of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks at Re = 3000. c Integrated vorticity transport and kinetic-energy gradient magnitudes of elliptical hydrodynamic cloaks against various Re’s. The integral domain is the red strip domain on the inset, considering the vorticity generated near the cloaking layer surface

According to the theoretical analysis, the convective term in the momentum transport equation \(\rho {\boldsymbol{u}}\cdot \nabla {\boldsymbol{u}}=\rho [\frac{1}{2}\nabla | {\boldsymbol{u}}{| }^{2}-{\boldsymbol{u}}\times (\nabla \times {\boldsymbol{u}})]\) is decomposed into two terms, which include the kinetic-energy gradient term \(\left(\frac{\rho }{2}\nabla | {\boldsymbol{u}}{| }^{2}\right)\) and vorticity transport term [−ρu × (∇ × u)]. In theoretical design, we ignore the vorticity transport term considering the irrotational pattern of the viscous potential flows and then transform the momentum transport equation into a Laplace-like equation serving as the foundation for hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks with the analytical solution.

To analyze the effect of the vorticity transport term and the kinetic-energy gradient term on cloaking effects, we will investigate the evolutionary characteristics of these two terms. Because the flow is oriented along the main axis (x-axis) of the elliptical object, it yields the vorticity transport term and kinetic-energy gradient term of the Y-component much smaller than that of the X-component, allowing the Y-component terms to be negligible (see Supplemental Material S.3). As shown in Fig. 3c, at Re values below 1000, the two X-components fall below very small, and the vorticity transport term is relatively negligibly smaller than the kinetic-energy gradient term (see Supplemental Material S.3). However, the vorticity transport rises progressively with increasing Re and can no longer be simply ignored compared to the kinetic-energy gradient, which ultimately hinders the realization of drag-reduction and cloaking effects.

Accordingly, it can be defined that the antagonism between the kinetic-energy gradient and vorticity transport determines the rationality of Laplace-like transformation for the momentum transport equation, which identifies the key factor to design the hydrodynamic cloaks with the analytical solution. Namely, when the vorticity transport term remains too insignificant to count compared with the kinetic-energy gradient term, the cloaking effect and the resolution of the D’Alembert paradox in viscous potential flows are guaranteed for hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks. Furthermore, it also enlightens that our paradigm not only applies to the viscous potential flows but to any real fluids as long as the vorticity among the flow fields is eliminated or the vorticity transport is negligibly overwhelmed by the kinetic-energy gradient. Finally, it implies that hydrodynamic cloaks might be an option to achieve Kelvin-Helmholtz hydrodynamic instability60 where vorticity deconstruction is a key factor to understand Kelvin-Helmholtz instability61, and a perspective to understand and study the lift62,63.

Although the design of the hydrodynamic zero-drag cloak proved to be successful, the proposed paradigm has not realized the hydrodynamic cloaks over Re of 3000 and is confined to laminar flows. In the experiment, a more effective method to realize higher-Re cloaking effects should be further explored. To overcome these challenges, comprehensive studies for higher-Re laminar flows and turbulent flows are required by factoring in the vorticity controlling and other turbulence-related terms. In addition, interdisciplinary research, such as optofluidics, magnetohydrodynamics, electroosmotic flows, and others, should be considered to extend the attainment of hydrodynamic cloaks under higher Re’s.

Conclusion

A paradigm for on-demand zero-drag hydrodynamic cloaks has been provided to resolve the D’Alembert paradox in viscous potential flows. By simplifying and transforming the Navier-Stokes equations into Laplace-like equations, hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks with the analytical solution are obtained, thus realizing the zero-drag characteristics over a large-Re range. This paradigm is experimentally validated by the thermostatically controlled method. Numerical results show that proposed hydrodynamic cloaks achieve zero-drag characteristics when Re’s remain under 1000, and continue to exhibit excellent drag-reduction effect even with the increase of Re up to 3000. Moreover, hydrodynamic cloaks can switch on and off at will, thus ensuring accurate flow manipulations. These findings offer promising possibilities for drag-free technology, offering valuable insights into microfluidics, biofluidics, and the manipulation of hypervelocity transportation travels hyperloop, among others. Ulteriorly, our research reveals that the vorticity transport directly impacts the performance of the drag-reduction effect and the cloaking effect. This insight suggests that vorticity controlling could be a potential method for designing hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks, and it may become a critical factor in realizing hydrodynamic zero-drag cloaks under higher Re’s, even in turbulent flows.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, J., Wen, J., Zhang, Z., Liu, H. & Sun, Y. Voyage inside the cell: microsystems and nanoengineering for intracellular measurement and manipulation. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 1, 1–15 (2015).

Zhao, X., Duan, G., Li, A., Chen, C. & Zhang, X. Integrating microsystems with metamaterials towards metadevices. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 5, 5 (2019).

Driels, M. & Ayyash, S. Drag reduction in laminar flow. Nature 259, 389–390 (1976).

Zhao, H., Sun, Q., Deng, X. & Cui, J. Earthworm-inspired rough polymer coatings with self-replenishing lubrication for adaptive friction-reduction and antifouling surfaces. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802141 (2018).

Benzi, R., Ching, E. S., Horesh, N. & Procaccia, I. Theory of concentration dependence in drag reduction by polymers and of the maximum drag reduction asymptote. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 078302 (2004).

Ma, X. et al. Hybrid superhydrophilic–superhydrophobic micro/nanostructures fabricated by femtosecond laser-induced forward transfer for sub-femtomolar raman detection. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 5, 48 (2019).

Brown, C. R. et al. Leakage pressures for gasketless superhydrophobic fluid interconnects for modular lab-on-a-chip systems. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 69 (2021).

Guo, L. et al. A bioinspired bubble removal method in microchannels based on angiosperm xylem embolism repair. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 34 (2022).

Park, S. et al. Bioinspired magnetic cilia: from materials to applications. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 153 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Designing a slippery/superaerophobic hierarchical open channel for reliable and versatile underwater gas delivery. Mater. Horiz. 10, 3351–3359 (2023).

Fu, M. K., Arenas, I., Leonardi, S. & Hultmark, M. Liquid-infused surfaces as a passive method of turbulent drag reduction. J. Fluid Mech. 824, 688–700 (2017).

Pendry, J. B., Schurig, D. & Smith, D. R. Controlling electromagnetic fields. Science 312, 1780–1782 (2006).

Leonhardt, U. Optical conformal mapping. Science 312, 1777–1780 (2006).

Urzhumov, Y. A. & Smith, D. R. Fluid flow control with transformation media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 074501 (2011).

Urzhumov, Y. A. & Smith, D. R. Flow stabilization with active hydrodynamic cloaks. Phys. Rev. E—Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 86, 056313 (2012).

Park, J., Youn, J. R. & Song, Y. S. Hydrodynamic metamaterial cloak for drag-free flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 074502 (2019).

Wang, H., Yao, N.-Z., Wang, B. & Wang, X.-S. Homogenization design and drag reduction characteristics of hydrodynamic cloaks. Acta Phys. Sinica 71, 20220346 (2022).

Jin, P. et al. Tunable liquid–solid hybrid thermal metamaterials with a topology transition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2217068120 (2023).

Fan, C., Gao, Y. & Huang, J. Shaped graded materials with an apparent negative thermal conductivity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 251907 (2008).

Li, J. Y., Gao, Y. & Huang, J. P. A bifunctional cloak using transformation media. J.Appl. Phys. 108, 074504 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. Temperature-dependent transformation thermotics: from switchable thermal cloaks to macroscopic thermal diodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 195503 (2015).

Shen, X., Li, Y., Jiang, C. & Huang, J. Temperature trapping: energy-free maintenance of constant temperatures as ambient temperature gradients change. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 055501 (2016).

Yang, F., Xu, L. & Huang, J. Thermal illusion of porous media with convection-diffusion process: transparency, concentrating, and cloaking. ES Energy Environ. 6, 45–50 (2019).

Chen, M., Shen, X. & Xu, L. Realizing the thinnest hydrodynamic cloak in porous medium flow. Innovation 3, 100263 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. Realizing the multifunctional metamaterial for fluid flow in a porous medium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207630119 (2022).

Jiang, C., Nie, H., Chen, M., Shen, X. & Xu, L. Achieving environmentally-adaptive and multifunctional hydrodynamic metamaterials through active control. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313986 (2024).

Park, J. & Song, Y. S. Laminar flow manipulators. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 40, 100908 (2020).

Park, J., Youn, J. R. & Song, Y. S. Metamaterial hydrodynamic flow concentrator. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 42, 101061 (2021).

Park, J., Youn, J. R. & Song, Y. S. Fluid-flow rotator based on hydrodynamic metamaterial. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 061002 (2019).

Pang, H., You, Y., Feng, A. & Chen, K. Hydrodynamic manipulation cloak for redirecting fluid flow. Phys. Fluids 34, 053603 (2022).

Pang, H., You, Y., Li, T., Chen, K. & Sheng, L. Design and reconfiguration of multicomponent hydrodynamic manipulation devices with arbitrary complex structures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 861 (2022).

Pang, H., Feng, A., You, Y. & Chen, K. Design of novel energy harvesting device based on water flow manipulation. Phys. Fluids 34, 093609 (2022).

Tay, F. et al. A metamaterial-free fluid-flow cloak. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwab205 (2022).

Wang, B., Shih, T.-M., Xu, L., Dai, G. & Huang, J. Intangible hydrodynamic cloaks for convective flows. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 034014 (2021).

Boyko, E. et al. Microscale hydrodynamic cloaking and shielding via electro-osmosis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 184502 (2021).

Ren, F., Wang, C. & Tang, H. Bluff body uses deep-reinforcement-learning trained active flow control to achieve hydrodynamic stealth. Phys. Fluids 33 (2021).

Wu, C.-L., Wang, B., Yao, N.-Z., Wang, H. & Wang, X. Meta-hydrodynamics for freely manipulating fluid flows. Phys. Fluids 36, 063613 (2024).

Wang, B. & Huang, J. Hydrodynamic metamaterials for flow manipulation: functions and prospects. Chin. Phys. B 31, 098101 (2022).

Chen, M., Shen, X. & Xu, L. Hydrodynamic metamaterials: principles, experiments, and applications. Droplet 2, e79 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Diffusion metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 218–235 (2023).

Yang, F. et al. Controlling mass and energy diffusion with metamaterials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 015002 (2024).

Stewartson, K. D’alembert’s paradox. SIAM Rev. 23, 308–343 (1981).

Eyink, G. L. Josephson-anderson relation and the classical D’alembert paradox. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031054 (2021).

Gao, Z., Ma, Y. & Zhuang, H. Drag minimization for navier–stokes flow. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equations: Int. J. 25, 1149–1166 (2009).

Osusky, L., Buckley, H., Reist, T. & Zingg, D. W. Drag minimization based on the navier–stokes equations using a newton–krylov approach. AIAA J. 53, 1555–1577 (2015).

Gömöry, F. et al. Experimental realization of a magnetic cloak. Science 335, 1466–1468 (2012).

Dudukovic, N. A. et al. Cellular fluidics. Nature 595, 58–65 (2021).

Feng, S. et al. Three-dimensional capillary ratchet-induced liquid directional steering. Science 373, 1344–1348 (2021).

Yue, S. et al. Gold-implanted plasmonic quartz plate as a launch pad for laser-driven photoacoustic microfluidic pumps. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6580–6585 (2019).

Lin, F. et al. Molding, patterning and driving liquids with light. Mater. Today 51, 48–55 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Multifunctional ferrofluid-infused surfaces with reconfigurable multiscale topography. Nature 559, 77–82 (2018).

Dunne, P. et al. Liquid flow and control without solid walls. Nature 581, 58–62 (2020).

Wang, Q., Jones III, A.-A. D., Gralnick, J. A., Lin, L. & Buie, C. R. Microfluidic dielectrophoresis illuminates the relationship between microbial cell envelope polarizability and electrochemical activity. Sci. Adv. 5, eaat5664 (2019).

Moazzenzade, T. et al. Self-induced convection at microelectrodes via electroosmosis and its influence on impact electrochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17908–17912 (2020).

Mac Huang, J. & Zhang, J. Rayleigh–bénard thermal convection perturbed by a horizontal heat flux. J. Fluid Mech. 954, R2 (2023).

Spalding, D. & Chi, S. The drag of a compressible turbulent boundary layer on a smooth flat plate with and without heat transfer. J. Fluid Mech. 18, 117–143 (1964).

Hele-Shaw, H. S. Flow of water. Nature 58, 520–520 (1898).

Kundu, P. K., Cohen, I. M. & Dowling, D. R. Fluid Mechanics (Academic Press, 2015).

Yao, N., Wang, H., Wang, B., Wang, X. & Huang, J. Convective thermal cloaks with homogeneous and isotropic parameters and drag-free characteristics for viscous potential flows. Iscience 25, 105461 (2022).

Mukherjee, B. et al. Crystallization of bosonic quantum hall states in a rotating quantum gas. Nature 601, 58–62 (2022).

Protas, B. & Sakajo, T. Harnessing the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability: feedback stabilization of an inviscid vortex sheet. J. Fluid Mech. 852, 146–177 (2018).

Lentink, D., Dickson, W. B., Van Leeuwen, J. L. & Dickinson, M. H. Leading-edge vortices elevate lift of autorotating plant seeds. Science 324, 1438–1440 (2009).

Cummins, C. et al. A separated vortex ring underlies the flight of the dandelion. Nature 562, 414–418 (2018).

Acknowledgements

N.Z.Y. and B.W. conceived the idea and designed the frame. N.Z.Y. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. B.W., T.M.S. and X.S.W. commented on the manuscript. N.Z.Y., B.W., H.W., C.L.W., T.M.S. and X.S.W. edited and revised the manuscript. This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12205102), and by Shanghai Science and Technology Development Funds (Grant No. 22YF1410600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, NZ., Wang, B., Wang, H. et al. On-demand zero-drag hydrodynamic cloaks resolve D'Alembert paradox in viscous potential flows. Microsyst Nanoeng 10, 188 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-024-00824-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-024-00824-z