Abstract

Myofibroblastic stromal hyperplasia (MSH) is the proposed name for a benign spindle cell proliferation of the mammary stroma, which often raises clinical and radiographic concern for a mass or a malignant process. Ten cases were retrieved from the files of our institution. All presented as a mammographic abnormality. Patients ranged in age from 24 to 67 years. Seven were <50 years old. The salient histopathologic aspect was the proliferation of benign appearing spindle cell within the intralobular stroma. The most common pattern was a diffuse proliferation of compact spindle cells with areas of perilobular/periductal accentuation. Mitotic activity and atypia were not seen. Tumor cells were positive for CD34 and SMA and negative for estrogen receptor, Beta-catenin, and p63. Only one of the cases demonstrated an associated lesion that explained the mammographic abnormality. Follow-up was available for four cases and was uneventful. MSH has overlapping features with the fascicular pattern of PASH and is likely related to pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) but differs in that does not demonstrate pseudovascular structures and it predominantly involves perilobular stroma. Recognition of this pattern will avoid discordant radiologic pathologic findings and unnecessary surgery/repeat biopsies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A wide range of stromal changes occur in the breast ranging from mass forming alterations, hyperplasias, and neoplastic lesions. Well-established, widely recognized benign lesions are pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) [1,2,3,4,5], benign fibrous tumor of the breast [6], fibrous mastopathy [7], and myofibroblastoma [8]. Fibromatosis, although not considered malignant, has however the potential to recur [9,10,11]. The most common malignant spindle cell lesions include metaplastic breast carcinomas, sarcomas, and phyllodes tumors [12, 13]. All these lesions may present as breast mass and clinically raise suspicion of malignancy. Breast biopsy is generally diagnostic and determines subsequent clinical management.

We have encountered in our practice a benign spindle cell lesion that raises clinical and radiographic suspicion for breast malignancy. Radiologically it may present as breast mass with poorly defined margins or as an area of architectural distortion and calcifications with BI-RADS score of 4A-5. It consists of bland spindle cell proliferation in perilobular stroma and with features consistent with a fascicular/proliferative from of PASH. The designation of myofibroblastic stromal hyperplasia (MSH) reflects the main histologic and immunophenotypic features of the lesion. The term nodular MSH was proposed some time ago for a mass forming lesion with typical features of PASH [14] but the cases we describe lack the usual features of PASH. It is important to recognize MSH as a mass forming lesion to avoid discordant radiologic pathologic findings and to differentiate it from periductal stromal tumors, which would require a substantially different treatment. The clinical, radiographic, histopathologic, and immunophenotypic features of MSH are described.

Materials and methods

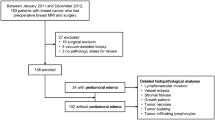

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. A retrospective search of the Washington University in St. Louis Department of Pathology and Immunology archive was searched from 1993 to 2013 for cases of MSH. Ten cases were identified that were diagnosed as MSH (a term used by one of the authors, HMM) and showed characteristic histopathologic features. Clinical and radiologic features were gathered from the electronic medical record. Hematoxylin and eosin slides were reviewed, and formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue blocks were retrieved for immunohistochemical studies (IHC). Pankeratin (AE1/AE3/PCK26, Ventana, Tucson AZ), keratin (34βE12, Ventana, Tucson AZ), cytokeratin 5/6 [(CK5/6), D5/16B4, Ventana, Tucson AZ], beta-catenin (14, Cell Marque, Rocklin CA), p63 (4A3, Ventana, Tucson AZ) estrogen receptor [(ER), SP1, Ventana, Tucson AZ], progesterone receptor [(PR), 1E2, Ventana, Tucson AZ], smooth muscle actin [(SMA), 1A4, Cell Marque, Rocklin CA], and CD34 (QBEnd/10, Ventana, Tucson AZ) (prediluted per standard protocol, single antibody stain procedure with adequate controls) were performed on eight cases at the Washington University AMP Core Laboratory. In addition, the pathology departmental archive was searched for all in-house breast core biopsies from 2014 to 2017 to aid in an approximate determination of the incidence of MSH.

Results

Ten cases of MSH were identified. Major clinical, radiographic, histopathologic, and immunophenotypic features are summarized in Table 1. All patients were female with a mean age of 48 years (range 24–67 years). Seven patients were <50 years old. Six patients were premenopausal, three were postmenopausal and in one patient the menopausal status was unknown. All but one case were unilateral.

The size of the lesion was known for 6 of the 10 lesions and ranged from 9 to 13 mm by imaging. BI-RADS score ranges for 4A to 5 in nine cases. Radiologic findings are presented in Table 1. Nine of ten cases underwent biopsy and resection was performed in one case. In four patients with available follow-up (mean 44 months, range 15–72 months), none had recurrences or other evidence of aggressive behavior. Out of 6044 in-house breast core biopsies from 2014 to 2017, MSH was identified in seven in-house core biopsies during that period (0.1%) but three times in 1215 (0.25%) biopsies signed by one the authors (HM) who has been using the term for more than 10 years. For comparison, in those 6044 in-house biopsies, fibromatosis was diagnosed two times (0.03%), PASH 98 times (1.6%), and benign spindle cell lesion (encompassing myofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma) 4 (0.06%).

Microscopic findings

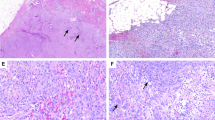

The most salient feature of the lesion at low magnification was the difference in stromal cellularity between involved and uninvolved areas, which were usually sharply demarcated (Fig. 1). Histologically, the tumors were composed of predominantly perilobular and periductal compact proliferation of spindle cells with uniform elongate nuclei with smooth nuclear membranes, finely dispersed chromatin devoid of nucleoli (Fig. 2 and 3). There was no cytologic atypia, mitoses, or necrosis. PASH was focally present in three cases and more diffusely in two. The spindle cell proliferation occasionally expanded beyond the immediate perilobular area, to form a few fields of purely stromal component (Fig. 4). The associated epithelium variably showed usual ductal hyperplasia, columnar cell change, and prominent myoepithelial cells. Accompanying breast lesions are detailed in Table 1. One case had coexistent atypical ductal hyperplasia, one case was associated with a fibroadenoma, and one case had atypical lobular hyperplasia. No cases were associated with malignancy).

Immunohistochemistry

IHC revealed that the lesions were positive for SMA (8/8) and CD34 (8/8) (Fig. 5), while negative for beta-catenin (0/8), ER (8/8), p63 (0/8), cytokeratin 34βE12 (0/8), and CK5/6 (0/8). PR was patchy in two cases, stained rare cells in 3 and was negative in 3. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3/PCK26 was focally weakly positive in two cases and negative in the remaining 6.

Discussion

Myofibroblastic proliferative lesions in the breast can be divided into presumed hyperplastic processes such as PASH and neoplastic ones, that is myofibroblastoma. PASH is believed to be hyperplastic and/or hormonally driven based on the patient’s age of presentation, generally premenopausal or postmenopausal women undergoing hormonal replacement therapy, the often multifocal nature of the lesion, and the cell positivity for PR. As its name indicates, the classical form is characterized by the presence of pseudovascular spaces seen in a dense collagenous background of the interlobular stroma [1,2,3,4,5]. A minority, however, are composed of solid cellular bundles of spindle cells devoid of gaping spaces and are described as the fascicular/proliferative form. Lobules and ducts are usually present throughout the lesion [4, 5]. Myofibroblastomas invariably present as a mass composed of solid cellular bundles of spindle cells devoid of lobular and ductal structures, except for those trapped at the periphery of the tumor [8]. The collagenized variant has hypocellular areas reminiscent of classic PASH.

The cellular characteristics and the IHC profile of MSH support its inclusion in the myofibroblastic group of lesions. The process we describe has the cellular composition of fascicular PASH, but it differs in is its particular distribution and accentuation around acini in the terminal ductal lobular unit and the absence of a significant component of classic PASH in most cases. Even in the more diffuse cases it appears to predominantly affect the intralobular stroma. The histopathologic differences with classic PASH can be explained by the characteristics of the background stroma in which the cells proliferate. Thus, in densely collagenized interlobular stroma, with limited space for cell proliferation, cells are spaced and restrained between collagen bundles, creating the pseudovascular spaces characteristic of PASH. The fascicular pattern may occur in areas in which collagen is less abundant and a looser myxoid matrix is present as is the usual composition of the perilobular stroma, an explanation advanced by Powell et al. [3]. The loose perilobular stroma offers minimal restrictions to cellular growth and the cells are compactly bundled together without interposed collagen and hence lack the pseudoangiomatous pattern. The marked periacinar accentuation may reflect an intrinsic property of the myofibroblastic cells or simply a limitation of the spread by the much denser perilobular stroma. The lesion depicted by Ferreira et al. as fascicular PASH is intralobular and is identical to the diffuse cases we encountered in this series [4].

Another important aspect of myofibroblastic proliferations is its relationship with the mammary epithelium. Gynecomastia-like epithelial changes have been described associated with PASH [4] in the female breast and PASH is often seen in the stroma of gynecomastia. Cases reported as gynecomastia-like lesion and PASH with gynecomastia-like changes in the female breast substantially overlap and may represent the same lesion [4, 15, 16]. PASH, classic and fascicular forms, are often seen in fibroadenomas and phyllodes tumor [17, 18], though the fascicular form is less likely to be recognized as PASH, as a spindled cell stroma is believed to be an inherent part of these fibroepithelial lesions. Fascicular PASH (or MSH) is sometimes seen in fibroepithelial lesions lacking the typical architectural features of fibroadenoma or phyllodes tumors, but still associated with an epithelial component, usually with some preserved lobular architectural features. These lesions have often been diagnosed as hamartomas. Fisher et al. found PASH in the stroma of 27 of 35 hamartomas [19] and PASH is seen in Fig. 6 of Daya’s article on mammary hamartomas [20]. Thus, it is possible that a proliferation of myofibroblasts elicits an accompanying epithelial cell proliferation with an architectural pattern that differs from conventional fibroadenomas.

The differential diagnosis elicited by MSH is unlike that of conventional PASH. Unlike classic PASH, vascular neoplasms do not enter the differential diagnosis when analyzing MSH. Stromal hypercellularity surrounding mammary epithelium is seen in phyllodes tumor and the likely related lesion periductal stromal tumor. The bland cytologic features of MSH, the absence of mitosis, and fat infiltration allow for separation from periductal stromal sarcoma and phyllodes tumor. Whereas the latter two tumors frequently present as palpable masses, MSH is almost invariably a solely radiologic finding. Furthermore, the characteristic architectural features of phyllodes tumors are absent in MSH. Consideration of desmoid fibromatosis may be elicited when the growth pattern is diffuse and is excluded by recognition of the usually limited nature of MSH, strong and diffuse staining with CD34, and the absence of wavy appearing nuclei and dense collagen. In addition, long sweeping fascicular architecture and extensive infiltrative growth typical of fibromatosis are not present in MSH. As some of the fibromatosis of the breast are β-catenin negative, this antibody is of limited utility in this setting although helpful when nuclear positivity is present. Metaplastic carcinomas, like fibromatosis, are mass forming lesions without lobular structures, and additionally show variable amounts of epithelial cords or nests. Mitosis are almost invariably found in the spindle and epithelial cells. Cytokeratin and p63 stains will highlight the epithelial component of the lesion and less frequently the spindle cells. Lastly, the lack of a defined tumor mass and the overall preservation of the breast architecture and epithelial-stromal relationship in MSH allows for distinction from mammary myofibroblastoma.

Our experience indicates that MSH is detected by mammography as a distinct lesion and its recognition is important to avoid labeling cases with only this diagnosis as discordant. As with the case of PASH, it is unlikely that radiologic features can be used to reliably diagnose this entity. Myofibroblastic proliferations can be present as a purely stromal lesion or associated with epithelial proliferation, in which case they may morphologically overlap or be part of hamartomas, gynecomastia, and gynecomastia-like lesions of the female breast as well as fibroadenomas and phyllodes tumors.

Data availability

Deidentified data and material are available upon request.

References

Vuitch MF, Rosen PP, Erlandson RA. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of mammary stroma. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:185–91.

Ibrahim RE, Sciotto CG, Weidner N. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of mammary stroma. Some observations regarding its clinicopathologic spectrum. Cancer. 1989;63:1154–1160.

Powell CM, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH). A mammary stromal tumor with myofibroblastic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:270–7.

Ferreira M, Albarracin CT, Resetkova E. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia tumor: a clinical, radiologic and pathologic study of 26 cases. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:201–7.

Drinka EK, Bargaje A, Erşahin ÇH, Patel P, Salhadar A, Sinacore J et al. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) of the breast: a clinicopathological study of 79 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20:54–58.

Rivera-Pomar JM, Vilanova JR, Burgos-Bretones JJ, Arocena G. Focal fibrous disease of breast. Virchows Arch A Path Anat Histol. 1980;386:59–64.

Tomaszewski JE, Brooks JS, Hicks D, Livolsi VA. Diabetic mastopathy: a distinctive clinicopathologic entity. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:780–6.

Magro G. Mammary myofibroblastoma: a tumor with a wide morphologic spectrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1813–20.

Rosen PP, Ernsberger D. Mammary fibromatosis. A benign spindle-cell tumor with significant risk for local recurrence. Cancer. 1989;63:1363–9.

Wargotz ES, Norris HJ, Austin RM, Enzinger FM. Fibromatosis of the breast. A clinical and pathological study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:38–45.

Norkowski E, Masliah-Planchon J, Le Guellec S, Trassard M, Courrèges J, Charron-Barra C, et al. Lower rate of CTNNB1 mutations and higher rate of APC mutations in desmoid fibromatosis of the breast: a series of 134 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1266–73.

Burga AM, Tavassoli FA. Periductal stromal tumor: a rare lesion with low-grade sarcomatous behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:343–8.

Al-Nafussi A. Spindle cell tumours of the breast: practical approach to diagnosis. Histopathology. 1999;35:1–13.

Leon ME, Leon MA, Ahuja J, Garcia FU. Nodular myofibroblastic stromal hyperplasia of the mammary gland as an accurate name for pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia of the mammary gland. Breast J. 2002;8:290–3.

Umlas J. Gynecomastia-like lesions in the female breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:844–7.

Kang Y, Wile M, Schinella R. Gynecomastia-like changes of the female breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:506–9.

Zanella M, Falconieri G, Lamovec J, Bittesini L. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of the mammary stroma: true entity or phenotype? Pathol Res. Pr. 1998;194:535–40.

Rosa G, Dawson A, Rowe JJ. Does identifying whether pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is focal or diffuse on core biopsy correlate with a PASH nodule on excision? Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:292–7.

Fisher CJ, Hanby AM, Robinson L, Millis RR. Mammary hamartoma—a review of 35 cases. Histopathology. 1992;20:99–106.

Daya D, Trus T, D’Souza TJ, Minuk T, Yemen B. Hamartoma of the breast, an underrecognized breast lesion. A clinicopathologic and radiographic study of 25 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:685–9.

Funding

No external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the cases. FK and JSAC compiled and tabulated the immunohistochemical and clinical data. HMM conceived the study. All authors contributed equally to the manuscript, reviewed it, and approved it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the IRB.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, F., Chrisinger, J.S.A. & Maluf, H.M. Myofibroblastic stromal hyperplasia of the breast. Mod Pathol 34, 1860–1864 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00834-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00834-6

This article is cited by

-

Clinicopathological analysis of three cases of breast desmoid-type fibromatosis

BMC Women's Health (2025)