Abstract

Background

Low maternal cognitive empathy and higher affective empathy have been linked to increased emotional-behavioral problems (EBPs) in young children, but it remains unclear whether the associations are distinct according to maternal depression. This study aims to explore the moderating role of maternal depression in the association between maternal empathy and EBPs in preschoolers.

Methods

Cross-sectional and representative data were from 19,965 Chinese preschoolers. Maternal cognitive and affective empathy and depression were evaluated with Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy and World Health Organization Five Well-Being Index, respectively. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was used to assess child EBPs.

Results

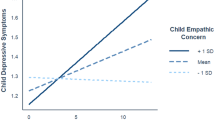

Lower maternal cognitive empathy was associated with increased child EBPs (aOR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.96–0.97) with moderation of maternal depression (p = 0.002), and was slightly stronger in mothers at low risk for depression (aOR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.95–0.97). Higher maternal affective empathy was associated with increased child EBPs (aOR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.02–1.04), without significant moderation (p = 0.79).

Conclusions

Lower maternal cognitive empathy and higher affective empathy were associated with more EBPs in preschoolers. Maternal depression moderated only the cognitive empathy-EBPs association. Tailored strategies targeting maternal empathy according to various depression levels should be considered in clinical practices.

Impact

-

We found lower maternal cognitive empathy and higher maternal affective empathy were associated with more emotional-behavioral problems (EBPs) in a large-scale and representative sample of preschoolers in Shanghai.

-

We demonstrated the moderating role of maternal depression in the association between maternal cognitive empathy and EBPs in preschoolers, with the association being slightly stronger in mothers at low risk for depression than in mothers with depressive symptoms.

-

The study highlights that, aside from maternal depression, promoting interventions on inappropriate maternal empathy may confer significant benefits on the psychological well-being of preschool children.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 14 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $18.50 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to shared ownership of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

References

Burke, J. D., Hipwell, A. E. & Loeber, R. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 49, 484–492 (2010).

Pardini, D. A. & Fite, P. J. Symptoms of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and callous-unemotional traits as unique predictors of psychosocial maladjustment in boys: advancing an evidence base for DSM-V. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49, 1134–1144 (2010).

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J. & Ridder, E. M. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 88, S14–S26 (2007).

Bronfenbrenner, U. & Morris, P. A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. in Handbook of Child Psychology 6th edn. (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006).

Kremer, P. et al. Normative data for the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for young children in Australia. J. Paediatr. Child Health 51, 970–975 (2015).

Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics 137, e20160339 (2016).

Hall, J. A., Schmid Mast, M. & Latu, I.-M. The vertical dimension of social relations and accurate interpersonal perception: a meta-analysis. J. Nonverbal Behav. 39, 131–163 (2015).

Cummings, E. M. & Davies, P. T. Maternal depression and child development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 35, 73–112 (1994).

Elgar, F. J., McGrath, P. J., Waschbusch, D. A., Stewart, S. H. & Curtis, L. J. Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 24, 441–459 (2004).

Meaney, M. J. Perinatal maternal depressive symptoms as an issue for population health. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 1084–1093 (2018).

Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E. & Neuman, G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 20, 561–592 (2000).

Reniers, R. L., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M. & Völlm, B. A. The QCAE: a questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. J. Personal. Assess. 93, 84–95 (2011).

Hoffman, M. L. in Emotions, Cognition, and Behavior 103–131 (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Abraham, E., Raz, G., Zagoory-Sharon, O. & Feldman, R. Empathy networks in the parental brain and their long-term effects on children’s stress reactivity and behavior adaptation. Neuropsychologia 116, 75–85 (2018).

Perez-Albeniz, A. & de Paul, J. Dispositional empathy in high- and low-risk parents for child physical abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 27, 769–780 (2003).

Dittrich, K. et al. Alterations of empathy in mothers with a history of early life maltreatment, depression, and borderline personality disorder and their effects on child psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 50, 1182–1190 (2020).

Ojha, A. et al. Empathy for others versus for one’s child: associations with mothers’ brain activation during a social cognitive task and with their toddlers’ functioning. Dev. Psychobiol. 64, e22313 (2022).

Psychogiou, L., Daley, D., Thompson, M. J. & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. Parenting empathy: associations with dimensions of parent and child psychopathology. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 26, 221–232 (2008).

Field, T., Diego, M. & Hernandez-Reif, M. Depressed mothers’ infants are less responsive to faces and voices. Infant Behav. Dev. 32, 239–244 (2009).

Merwin, S. M., Leppert, K. A., Smith, V. C. & Dougherty, L. R. Parental depression and parent and child stress physiology: moderation by parental hostility. Dev. Psychobiol. 59, 997–1009 (2017).

Maughan, A., Cicchetti, D., Toth, S. L. & Rogosch, F. A. Early-occurring maternal depression and maternal negativity in predicting young children’s emotion regulation and socioemotional difficulties. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 35, 685–703 (2007).

Wang, X. et al. Cohort profile: the Shanghai Children’s Health, Education and Lifestyle Evaluation, Preschool (SCHEDULE-P) study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 391–399 (2021).

Meade, A. W. & Craig, S. B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 17, 437–455 (2012).

Liang, Y. S. et al. Validation and extension of the questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy in the Chinese setting. PsyCh. J. 8, 439–448 (2019).

Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 1337–1345 (2001).

Du, Y., Kou, J. & Coghill, D. The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in China. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2, 8 (2008).

Kou, J., Du, Y. & Xia, L. Reliability and validity of “children strengths and difficulties questionnaire” in Shanghai norm. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 17, 25–28 (2005).

Fung, S. F. et al. Validity and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the 5-item WHO well-being index. Front. Public Health 10, 872436 (2022).

Aujla, N., Skinner, T. C., Khunti, K. & Davies, M. J. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in a white European and South Asian population with impaired glucose regulation and screen-detected type 2 diabetes mellitus: a comparison of two screening tools. Diabet. Med. 27, 896–905 (2010).

Staehr-Johansen, K. Well-Being Measures in Primary Health Care—the Depcare Project. (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Geneva, World Health Organization, 1998).

Lipsky, A. M. & Greenland, S. Causal directed acyclic graphs. Jama 327, 1083–1084 (2022).

Textor, J., Hardt, J. & Knüppel, S. Dagitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 22, 745 (2011).

Cooke, J. E., Racine, N., Pador, P. & Madigan, S. Maternal adverse childhood experiences and child behavior problems: a systematic review. Pediatrics 148, e2020044131 (2021).

Dadds, M. R. et al. A measure of cognitive and affective empathy in children using parent ratings. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 39, 111–122 (2007).

Hu, Y., Emery, H. T., Ravindran, N. & McElwain, N. L. Direct and Indirect pathways from maternal and paternal empathy to young children’s socioemotional functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 34, 825–835 (2020).

Hawk, S. T. et al. Examining the interpersonal reactivity index (IRI) among early and late adolescents and their mothers. J. Pers. Assess. 95, 96–106 (2013).

Liu, H. & Yuan, K. H. New measures of effect size in moderation analysis. Psychol. Methods 26, 680–700 (2021).

Bi, S. & Keller, P. S. Parental empathy, aggressive parenting, and child adjustment in a noncustodial high-risk sample. J. Interpers. Violence 36, Np10371–np10392 (2019).

Bremner, J. G. & Wachs, T. D. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 2, Applied and Policy Issues 2nd edn (The Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

Stein, A. et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 384, 1800–1819 (2014).

Walker, L. O. & Cheng, C. Y. Maternal empathy, self-confidence, and stress as antecedents of preschool children’s behavior problems. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 12, 93–104 (2007).

Waller, R., Shaw, D. S., Forbes, E. E. & Hyde, L. W. Understanding early contextual and parental risk factors for the development of limited prosocial emotions. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 1025–1039 (2015).

Crocetti, E. et al. The dynamic interplay among maternal empathy, quality of mother-adolescent relationship, and adolescent antisocial behaviors: new insights from a six-wave longitudinal multi-informant study. PLoS ONE 11, e0150009 (2016).

Trentacosta, C. J. & Shaw, D. S. Maternal predictors of rejecting parenting and early adolescent antisocial behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 36, 247–259 (2008).

Oppenheim, Koren-Karie, N., Abraha & David. Mothers’ empathic understanding of their preschoolers’ internal experience: relations with early attachment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 25, 16–26 (2001).

Hoemann, K., Xu, F. & Barrett, L. F. Emotion words, emotion concepts, and emotional development in children: a constructionist hypothesis. Dev. Psychol. 55, 1830–1849 (2019).

Trentacosta, C. J. & Fine, S. E. Emotion knowledge, social competence, and behavior problems in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Soc. Dev. 19, 1–29 (2010).

Bird, G. et al. Empathic brain responses in insula are modulated by levels of alexithymia but not autism. Brain 133, 1515–1525 (2010).

Banzhaf, C. et al. Interacting and dissociable effects of alexithymia and depression on empathy. Psychiatry Res. 270, 631–638 (2018).

Kaźmierczak, M., Pawlicka, P., Łada-Maśko, A. B., van, I. M. H. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. How well do couples care when they are expecting their first child? family and dyadic predictors of parental sensitivity in expectant couples. Front. Psychiatry 11, 562707 (2020).

Kenny, D. A. & Acitelli, L. K. Accuracy and bias in the perception of the partner in a close relationship. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 80, 439–448 (2001).

Knafo, A. & Uzefovsky, F. in The Infant Mind: Origins of the Social Brain 97–120 (The Guilford Press, 2013).

Warrier, V. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of cognitive empathy: heritability, and correlates with sex, neuropsychiatric conditions and cognition. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1402–1409 (2018).

Leerkes, E. M. & Crockenberg, S. C. Antecedents of mothers’ emotional and cognitive responses to infant distress: the role of family, mother, and infant characteristics. Infant Ment. Health J. 27, 405–428 (2006).

Bell, R. Q. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychol. Rev. 75, 81–95 (1968).

Horan, W. P. et al. Structure and correlates of self-reported empathy in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 66-67, 60–66 (2015).

Leerkes, E. M. Predictors of maternal sensitivity to infant distress. Parent. Sci. Pract. 10, 219–239 (2010).

Cole, P. M., Michel, M. K. & Teti, L. O. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: a clinical perspective. Monogr. Soc. Res Child Dev. 59, 73–100 (1994).

Cusi, A. M., Macqueen, G. M., Spreng, R. N. & McKinnon, M. C. Altered empathic responding in major depressive disorder: relation to symptom severity, illness burden, and psychosocial outcome. Psychiatry Res. 188, 231–236 (2011).

Schreiter, S., Pijnenborg, G. H. & Aan Het Rot, M. Empathy in adults with clinical or subclinical depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 150, 1–16 (2013).

Funding

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82071493), the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 2022you1-2), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 2018SHZDZX05), and the Innovative Research Team of High-level Local Universities in Shanghai (No. SHSMU-ZDCX20211900, SHSMU-ZDCX20211100). Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (No. 2020CXJQ01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zichen Zhang conceptualized the study; contributed to the data collection, design, and conduct of data analysis; and drafted the initial manuscript. Yujiao Deng contributed to the conduct of data analysis and drafted and revised the manuscript. Tingyu Rong, Yiding Gui, Yunting Zhang, Jin Zhao, Wenjie Shan, and Qi Zhu contributed to the data collection and revision of the draft. Guanghai Wang supervised the data collection, conceptualized and designed the study, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Fan Jiang coordinated and supervised the data collection, conceptualized and designed the study, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received approval from the institutional review board of the Shanghai Children’s Medical Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SCMCIRB-K2016022-01). Parents of the involved children signed the informed consent before participating in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Deng, Y., Rong, T. et al. Maternal cognitive and affective empathy related to preschoolers’ emotional-behavioral problems: moderation of maternal depression. Pediatr Res 98, 551–558 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03770-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03770-8