Abstract

The increasing prevalence of pediatric hypertension is concerning to our population because cardiovascular diseases are a leading cause of death in adults. Studies have shown that sleep disturbances in children, such as sleep fragmentation, increase blood pressure and lead to adult hypertension. However, the mechanisms by which this occurs are not fully understood. Most studies regarding sleep disturbances and hypertension are within adults, leaving the adolescent population understudied. In this review, we will describe the physiology of sleep, compare blood pressure variations between adults and adolescents, and discuss social issues regarding sleep fragmentation in children. In addition, we will also discuss the limitations of the studies available and what future research needs to be conducted.

Impact

-

Pediatric hypertension is a complex condition that has various underlying causes, thus making treatments complicated.

-

We describe the physiology of sleep, compare blood pressure variations between adults and adolescents, and discuss social issues regarding sleep fragmentation in children.

-

We synthesize and connect studies to enhance knowledge of the issues that lead to the development of hypertension in pediatrics.

-

We show the limitations of previous studies and describe future research that can further our understanding in the development of pediatric hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Examination of blood pressure (BP) during sleep is possible with the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.1 BP follows a circadian rhythm and falls during sleep. The fall in pressure, called the “dip”, is defined as the difference between daytime mean systolic pressure and nighttime mean systolic pressure expressed as a percentage of the day value. A dip of 10–20% is considered normal. Dips less than 10%, referred to as blunted or absent, have been considered as predictors for adverse cardiovascular events, though it is not definitive.2 It is important to note that BP is defined differently between adults and youth. Adult hypertension is defined mainly by clinical outcomes such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk and mortality. Youth BP is defined from the normative distribution of BP data in healthy children. Table 1 summarizes BP categories and hypertension stages in children.3

Height, sex, and age are important determinants of pediatric BP. Recent studies show that body size [height, weight, and body surface area (BSA), but not BMI] influences cardiac output and vascular resistance, affecting diastolic blood pressure in young adults. Larger individuals tend to have higher cardiac output and lower vascular resistance when lying down, and greater resistance increases upon standing.4 These findings suggest that incorporating body size—especially BSA—into blood pressure assessment could improve accuracy and reduce misdiagnosis of hypertension. Although more research is needed in children, current monitoring standards may benefit from refinement using advanced modeling to account for individual variability. Chronic cardiovascular consequences like left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) can occur in childhood, although not as common as in adults.3,5 In a study assessing longitudinal BP trajectories from childhood and the impact of level-independent childhood BP trajectories on adult LVH, Zhang et al., (2018) reported the association of childhood BP linear slopes with concentric LVH was significantly stronger than that with eccentric LVH during the adolescence period of 12 to 19 years. These observations indicate that the impact of BP trajectories on adult LVH and geometric patterns originates in childhood, highlighting importance for early prevention.6 In a meta-analysis assessing the prevalence of LVH and its determinants in children with primary hypertension, only body mass index (BMI) z-score was significantly associated with LVH prevalence (estimate 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.39, p = 0.004) and accounted for 41% of observed heterogeneity, but not age, male percentage, BMI, or waist circumference z-score. The predominant LVH phenotype was eccentric LVH in patients from specialty clinics (prevalence of 22% in seven studies with 779 participants) and one community screening study reported the predominance of concentric LVH (12%).7 These findings provide insight into significant risk factors for LVH in hypertensive youth. In comparison to adults, pediatric hypertension is predominately a sequela of renal pathology.8 Globally, pediatric chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been estimated to be 15–74.7 children per million; excluding rates in North America due to lack of data.9 In a study investigating left ventricular mass and the factors associated with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in children with stages 2–4 chronic kidney disease, 38% of participants had masked hypertension (normal casual blood pressure but elevated ambulatory blood pressure), while 18% had confirmed hypertension (elevated casual and ambulatory blood pressure). Although there was no significant link between LVH and kidney function, LVH was notably more prevalent in children with confirmed (34%) or masked (20%) hypertension compared to those with normal casual and ambulatory blood pressure (8%). Multivariable analysis revealed that masked hypertension (odds ratio 4.1) and confirmed hypertension (odds ratio 4.3) were the strongest independent predictors of LVH. The authors noted that these findings highlight that casual blood pressure measurements alone are inadequate for predicting LVH in children with CKD. The authors also noted that given the high prevalence of masked hypertension and its correlation with LVH, early echocardiography and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring may be useful in assessing cardiovascular risk in this population.10

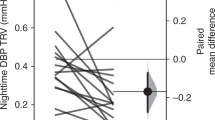

Although there are differences in the definition of high BP between adults and youth, studies report that pediatric dipping should normally be ≥10%.11 While a nocturnal blood pressure dip of over 10% is commonly used as a standard, this threshold has several important limitations. In pediatric populations, it fails to reflect the developing circadian rhythm of blood pressure in children and shows poor reproducibility due to daily variability.12,13 It also overlooks individual circadian preferences and the impact of irregular sleep patterns.14,15,16,17 Additionally, studies have shown that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring itself may disrupt sleep due to cuff inflation, particularly within the first 24 h of use, potentially compromising both sleep quality and the accuracy of the measurements.18 However, assessing dipping status is helpful in determining whether adult patients are at risk of cardiovascular events. In adult CKD patients, it is common to have a loss of the typical nocturnal decline in BP by 10%–20% and is associated with LVH and adverse cardiovascular events.19,20 Yilmaz et al. (2007) showed that night-time mean systolic BPs, diastolic BPs, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores were significantly higher in non-dippers (mean nighttime SBP 136 ± 15, mean nighttime DBP 84 ± 12, percent dipping in SBP,1.4 ± 5.9, percent dipping DBP 2.3 ± 7.4, and PSQI 6.76 ± 3.11) compared with dippers (mean nighttime SBP 123 ± 12, mean nighttime DBP 76 ± 9, percent dipping in SBP 14.3 ± 4.6, percent dipping DBP 16.1 ± 6.5, and PSQI 5.16 ± 2.92). Being a poor sleeper in terms of a high PSQI score (total score>5) was associated with a threefold increased risk of being a non-dipper.21 In a separate study evaluating factors affecting circadian BP profile and its association with hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) in pediatric patients with primary hypertension (PH), the nocturnal SBP decrease correlated with BMI Z-score and left ventricular mass index (LVMI) while diastolic DBP decrease correlated with augmentation index (AIx75HR). Patients with a disturbed blood pressure profile (nocturnal drop in SBP or DBP) <10% had the highest LVMI, while extreme dippers (nocturnal drop >20%) had the highest augmentation index (AIx75HR). The authors concluded in pediatric patients with PH, non-dipping is associated with increased left ventricular mass, and extreme dipping may be a risk factor for increased arterial stiffness. Within the same study, non-dipping was found in 44.6% of patients and extreme dipping was found in 25.9% of pediatric patients. These findings highlight the importance of the relationship between poor sleep and cardiovascular function.22

Two adult population-based cohort studies found that subjects with intermediate (3–4 ideal metrics) and ideal ( ≥5 ideal metrics) global cardiovascular health (CVH) had lower odds of self-reported sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in both cohorts.23 Although based on self-reported SDB, the study was able to show that poor sleep is associated with poor CVH in humans and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. A majority of studies available regarding blood pressure and sleep are focused on adults. Youth sleep fragmentation (SF) and its impact on hypertension are understudied and need more research. Although not related to SF, a systematic review of prospective cohorts revealed that elevated BP in childhood or adolescence was significantly associated, in adulthood, with high pulse wave velocity; high carotid intima-media thickness; and left ventricular hypertrophy.24 Articles reporting combined effects of child (or adolescent) and adult elevated BP on CVD outcomes in adulthood were also included. In addition to cardiovascular compromise, a systematic review on cognitive testing among children and adolescents with primary arterial hypertension (PAH) reported worse results among individuals with PAH. Results of two prospective trials suggested that cognitive functioning may improve after starting antihypertensive treatment.25,26 Significant confounders, namely obesity and sleep apnea, were identified throughout the studies. The review indicates that evidence relating AH with poor cognitive functioning among youth is usually based on indirect measures of executive functions (e.g., questionnaires) rather than objective neuropsychological tests and further studies should be conducted.27 These findings highlight the importance of detecting youth hypertension in order to prevent serious adverse events.

The purpose of this systematic review was to determine the mechanisms by which pediatric hypertension occurs and the social/economic effects on pediatric blood pressure. Data from both animal models and clinical studies were examined to understand the effects of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents and the future health consequences in adults. Lastly, we explore the effects of poor sleep in general and discussed improving overall health to combat the increasing incidence of hypertension. A full list of abbreviations used in this manuscript is found in Supplementary Table 1 (S1).

Developmental changes in sleep wake cycle

The sleep-wake cycle changes throughout development, generally showing a gradual decrease in sleep duration and a shift to a later sleep phase, with more significant changes occurring during adolescence. These alterations are accompanied by changes in neuroendocrine rhythms (e.g., melatonin, cortisol) and circadian rhythms (e.g., body temperature) (Fig. 1).

aThe hours of sleep (aqua) needed decreases from newborn to young adulthood. During the first few months, sleep duration includes frequent napping. The sleep wake cycle is established during the first 6 months of life, during which frequency and duration of naps decreases. b 24-h rhythm of the sleep-wake cycle, core body temperature (black), cortisol (magenta) and melatonin (blue) secretion from infancy to 20 years of age. The shortening in sleep duration (gray shading), is accompanied by a delay in the sleep-wake cycle, during adolescence.

Throughout infancy and childhood, sleep patterns become more consolidated, leading to fewer and shorter daytime naps. The average sleep duration also steadily decreases over this time, from 12.8 h in infants to 11.9 h for children aged 2–5 years.28 This trend (Fig. 1a) continues through childhood, with 6–12-year-olds averaging 9.2 h, adolescents around 16 years old getting 8.1 h, and adults around 24 years old sleeping about 7.5 h.28,29,30

Furthermore, the pineal hormone melatonin plays an important role in regulating sleep wake cycle. It exhibits a 24-h secretion pattern, starting in the evening, peaking during the night, and decreasing in the morning.31 This daily rhythm of melatonin strengthens around ages 4–7, and gradually diminishes in intensity throughout one’s lifespan.32,33,34 Cortisol secretion also follows a circadian rhythm, starting with high levels upon waking in the morning, peaking about 30 min later, and gradually decreasing throughout the day to reach its lowest levels around bedtime.35,36 During adolescence, cortisol levels rise and the rhythm becomes flatter as age and pubertal development progress.37,38 A circadian rhythm of core body temperature (CBT) is established within the first year of life, peaking during the day and dropping to its lowest point at night, a few hours after sleep onset. This rhythm is more pronounced in children than in adults.37,39,40,41 A later timing of the CBT rhythm is linked to eveningness (i.e., later bed and rise times) in adolescents and adults, and the rhythm tends to shift to an earlier phase as people age.42,43,44

Physiologic consequences of sleep disturbances

Poor sleep has been associated with elevated BP but there are other serious health effects involved as well. In addition to BP changes, a sleep fragmentation (SF) mouse model study demonstrated that long-term SF induces vascular endothelial dysfunction. Elastic fiber disruption and disorganization were also noted in the SF aortas compared to control aortas and fiber disorganization were apparent in SF-exposed mice (p < 0.01). Additionally, an increased recruitment of inflammatory cells and altered expression of senescence markers were noted in the SF-exposed mice.45

In addition to endothelial dysfunction, changes in the gut microbiome play a role in blood pressure regulation. Using a rat model of SF, Maki et al. (2020) examined the relationship between gut microbiota, blood pressure, and sleep. The SF rats with gut microbiome changes were also found to have significantly higher mean arterial pressure (MAP), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate compared to control rats.46 These findings suggest that in addition to vascular changes and inflammation, changes in the gut microbiome associated with SF and other sleep disturbances also play a role in the development of hypertension. This animal study highlights potential biochemical mechanisms that lead to cardiovascular compromise and should be studied further.

Sleep disturbances have also been associated with metabolic syndrome (MetS). Metabolic syndrome refers to abnormalities in glucose and lipid metabolism, potentially caused by insulin resistance and/or central obesity. MetS is estimated to affect more than 20% of United States adults, who frequently progress to diabetes and are at increased risk for premature cardiovascular disease.47 A study of children with SDB (apnea-hypopnea index ⩾5) showed 6.5 greater odds of MetS compared with children without SDB. Analyses of the individual metabolic parameters showed that SDB was associated with elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and fasting insulin levels after adjustment for body mass index.48 Identifying a relationship between sleep and cardiovascular health is of particular interest because the ability to correct sleep disturbances can help prevent serious long-term health conditions, especially in adolescents.

Adolescents and sleep

Although the data on adolescents and sleep is limited, there are many contributing factors that can lead to disordered sleep in adolescents. Recent studies of adolescents have shown that the delayed internal clock phase is associated with secondary-sex development. This finding suggests a biological component to adolescent changes in sleep patterns. Other mammalian species also show similar changes in the timing of sleep and activity around the development of sexual maturation as evidenced by the review of Hagenauer et al.49 There are two mechanisms underlying the changes in the sleep pattern of adolescents: homeostatic drive and circadian timing system. Normally, the circadian timing system promotes sleep in the evening and wakefulness in the morning. The homeostatic drive for sleep or sleep pressure increases the longer the person stays awake and decreases during sleep. However, in adolescence, there is a resistance to sleep pressure which consequently delays the onset of sleep. Additionally, their circadian phase becomes delayed, which causes them to stay awake later in the evening.50

Older adolescents have later bedtimes than younger adolescents. This delayed timing of sleep has been attributed to external factors such as evening work,51 however, evidence suggests that external factors alone do not completely account for the adolescent delayed sleep onset. The transition into a more evening chronotype—due to a delayed circadian phase—in the second decade of life has been observed across different cultures. This transition is maintained even after weeks of regulated schedules of sleep and under controlled laboratory conditions in which there is limited influence by external factors.52 A delayed sleep phase occurs when the sleep pattern becomes delayed two hours or more from conventional or normal sleep patterns; this usually causes a delay in sleep and a later rise time.

Additionally, Taylor et al., used Tanner staging, an objective classification system of pubertal development of secondary sex characteristics to compare different stages in adolescents.53 In a study aimed at assessing sleep latency, a measure of sleep tendency (speed of falling asleep), sleep latency after waking did not differ at 20:30 h, but was shorter for the Tanner 1 group at 22:30 h (Tanner 1 = 9.2 ± 6.3 min; Tanner 5 = 15.7 ± 5.8 min), 00:30 h (Tanner 1 = 3.6 ± 1.7 min; Tanner 5 = 9.0 ± 6.4 min), and 02:30 h (Tanner 1 = 2.0 ± 1.7 min; Tanner 5 = 4.3 ± 3.2 min) indicating that more mature adolescents are slower to fall asleep in the evening compared to younger adolescents.54 Jenni et al., showed that the homeostatic drive for sleep or the pressure to sleep caused by sleep deprivation was slower in post-pubertal than prepubertal children, reporting a time of 15.4 ± 2.5 h for Tanner 5 adolescents (post-pubertal) and 8.9 ± 1.2 h for those in Tanner stage 1 or 2 (prepubertal).55

Both studies suggest that post-pubertal adolescents have a greater tolerance for prolonged waking episodes. Recent evidence suggests that light sensitivity of the circadian system is altered during puberty such that there is an increased sensitivity to the phase-delaying effects of light.56 One study found that post pubertal adolescents were significantly less sensitive to dim light exposure in the morning (3:00–4:00) than pre-pubertal adolescents.57 These findings suggest that the endogenous circadian system undergoes certain changes at the onset of puberty. However, more research needs to be conducted regarding the association between the observed delay in the circadian phase during puberty.

There are several factors that contribute to insufficient sleep and poor sleep quality in both adolescents and adults including the onset of puberty. US and international studies58,59,60 have reported that adolescents get less sleep as they get older. According to the national sleep foundation, 75% of 12th graders self-reported a sleep duration of less than 8 h, compared to just 16% of 6th graders. This pattern was also observed in other countries as reported by a study in 2005 that more than 1400 South Korean adolescents experienced a reduced sleep duration in high school, with an average sleep duration of 4.9 h.61 The decreased sleep duration with increased age among adolescents has been attributed to biologically driven processes due to the onset of puberty. Roenneberg et al.,62 reported a 2-h delay for girls and a 3 h delay for boys in the midpoint of sleep—clock time between sleep onset and waking up—across the second decade. Furthermore, the sleep-wake homeostasis, responsible for balancing our need for sleep (sleep pressure or sleep drive) with our need for wakefulness is altered to favor late-night sleep timing as adolescents age.63 Recent data seem to indicate that more mature adolescents accumulate sleep pressure at a much slower rate compared to younger adolescents.55

Additionally, epidemiologic studies have indicated that individuals from families with low income or of racial or ethnic minorities are at a greater risk of poor quality and insufficient sleep, which contributes to the disparities observed in sleep health.64,65 Those with lower socioeconomic status had a less consistent schedule.66 Furthermore, several household variables have been identified as factors influencing sleep schedules and quality including overcrowding, noise levels, and safety concerns. Families facing overcrowded living conditions or residing in noisy and unsafe environments may have greater difficulties in maintaining consistent sleep schedules and achieving adequate sleep.67 Children from disadvantaged backgrounds often face barriers to accessing quality healthcare, including regular pediatric check-ups and management of chronic conditions. In a study aimed at identifying a connection between area-level socioeconomic indicators and the likelihood of completing or not completing preventative services in pediatric primary care centers, they discovered that patients residing in communities or census tracts with higher poverty rates and limited access to vehicles were approximately 30% less inclined to complete essential preventive services when compared to those living in areas with the lowest poverty rates and highest vehicle access, respectively. This limited access to healthcare services may result in undiagnosed and uncontrolled high blood pressure in children.68

It has been reported in numerous studies that simultaneous use of multiple electronic devices is associated with decreased sleep at night. A children’s study in 1976 found that adolescents who watched three or more hours of television had difficulty falling asleep and experienced disrupted sleep throughout the night.69 A study of subjects from suburban Philadelphia showed that out of 100 adolescents ranging in age from 12 to 18 years, one-third of the participants had a computer, two-thirds had a television, and 90% had a cell phone in their bedroom. These teenagers were also reported to have simultaneously engaged in an average of four electronic activities after 9 pm.70 A possible mechanism postulated for the effects of electronic use on sleep is that it suppresses the release of melatonin due to the light generated by the electronic devices, which consequently disrupts the body’s internal clock.71 Several studies have demonstrated that low-intensity light can decrease melatonin secretion at night72 and alter circadian rhythms.73,74

In addition to its established impact on circadian rhythms and melatonin suppression, evening light exposure has been shown to directly influence cardiovascular physiology, including blood pressure regulation. Importantly, research has demonstrated that exposure to light, particularly in the evening, can acutely elevate blood pressure through non-circadian pathways.75 For instance, research indicates that exposure to moderate-intensity light (700 lux, fluorescent) can reduce vagal activity in the autonomic nervous system.76 Additionally, exposure to high-intensity light (over 5000 lux, LED) significantly elevates heart rate by enhancing sympathetic nervous system activity.77

Moreover, epidemiological evidence supports a broader association between nighttime light exposure and the prevalence of hypertension across different age groups. A study by Obayashi et al. (2014) demonstrated that even low levels of nighttime light exposure ( ≥5 lux) in home settings are associated with increased nighttime systolic and diastolic blood pressure in elderly individuals, highlighting light at night (LAN) as a significant environmental factor affecting cardiovascular health. This association remained significant after adjusting for potential confounding variables, including overnight urinary melatonin excretion and sleep quality, suggesting that the impact of LAN on blood pressure operates independently of circadian hormone regulation and sleep disruption.78 In another study, Xu et al. (2023) investigated the relationship between objectively measured bedroom LAN exposure and blood pressure in a sample of Chinese young adults aged 16–22 years. The study found that higher levels of LAN were significantly associated with elevated SBP and a greater risk of hypertension, even in this relatively healthy, young population. Specifically, each 1 lux increase in bedroom LAN intensity corresponded to a 0.55 mmHg increase in SBP.79 These observations suggest that in addition to sleep disruption, light exposure may serve as a direct environmental risk factor for pediatric hypertension.

Moreover, although caffeine use in adolescents has not been extensively studied, it has been reported to have deleterious effects on their sleep patterns. Caffeine consumption among adolescents is associated with shorter sleep duration, increased sleep onset latency, and increased wake time after sleep onset.80,81,82 In 2008, Roehrs and Roth concluded that high and regular caffeine users experienced disrupted sleep, which led to more daytime sleepiness and that in turn led to more caffeine consumption during the day.83

Adolescent sleep disturbances and hypertension

There are several modifiable and non-modifiable confounders in the development of hypertension in adolescents (Table 2,84,85,86,87,88,89). Javaheri et al. conducted a cross-sectional study that assessed whether insufficient sleep is associated with prehypertension in healthy adolescents.90 After adjustment for the same variables, those with polysomnography sleep efficiency ≤85% had nearly 3 times the odds of prehypertension as those with better sleep (OR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.28, 6.24). However, it is important to note that the correlation between actigraphy sleep efficiency and PSG sleep efficiency was low (r = 0.13, p = 0.04). Approximately one-third (32.8%) of adolescents with low sleep efficiency as assessed on actigraphy also had low sleep efficiency from the polysomnography. In a study comparing actinography and PSG, sleep onset latency (SOL) and wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) measurements had some disagreement.91 After Bland-Altman concordance between actinography and PSG, the disagreement between measurement modalities increased as the average value of SOL or WASO increased. This indicates that actigraphy may be less accurate by falsely reporting long periods of quiet wakefulness as sleep (shorter SOL) or reporting body movements for disturbed sleep (longer SOL). While actigraphy is an accurate method for measuring sleep, PSG remains the gold standard. Within the same study, the authors also compared sleep diaries to actinography and PSG. Sleep diaries, which are a form of subjective sleep measurement, had statistically significant differences for all variables with actinography and PSG.91 Although subjective measures such as surveys and diaries are inexpensive and accessible, they are less accurate and more biased. A variety of methods are available to assess sleep in children and adolescents, each with specific strengths, limitations, and criteria (see Table 3 for a detailed comparison).

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypertension

In another study, blood pressure was measured during polysomnography in 41 children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and compared to 26 children with primary snoring (PS).92 OSA is characterized by episodes of complete collapse of the airway or partial collapse with an associated decrease in oxygen saturation or arousal from sleep resulting in fragmented, nonrestorative sleep.93 The results showed that children with OSA had a significantly higher diastolic BP than those with PS (p < 0.001 for sleep and p < 0.005 for wakefulness). In adults with OSA, symptoms typically include daytime somnolence whereas children with OSA are more likely to present with behavioral and cognitive disorders, including hyperactivity, attention-deficit disorder, poor school performance, and nocturnal enuresis.94 OSA diagnosis is based on polysomnography (PSG) results. According to the 2012 AASM scoring manual, the criteria for events during sleep for infants and children can be used for those who are 18 years younger of age, but individual sleep specialists can choose to score children who are 13 years of age or older using adult criteria. The severity of OSA can be categorized by the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI). In a study assessing the predictors for pediatric hypertension, late childhood/adolescence, obesity, and severe OSA were independent predictors. Furthermore, late childhood/adolescence, and abnormal SpO2 (mean SpO2 < 95%) independently predicted hypertension in obese children. Severe OSAS independently predicted hypertension in non-obese children.95 Although PSG is the gold standard, it is important to note that the PSG and BP measurements are often recorded for one night and in a clinical research building which could contribute to changes in blood pressure and sleep. Additionally, one recording may not represent the true blood pressure or sleep parameters due to variability in individual sleep specialist scoring children based on age.

In a longitudinal study by Chan et al. (2020), childhood moderate-to-severe OSA was associated with higher nocturnal systolic blood pressure (SBP) (difference from normal controls: 6.5 mmHg, 95% CI 2.9–10.1) and reduced nocturnal dipping of SBP ( − 4.1%, 95% CI − 6.3% to 1.8%) at follow-up, adjusted for age, sex, BMI and height at baseline, regardless of the presence of OSA at follow-up.96 Childhood moderate-to-severe OSA was also associated with higher risk of hypertension (relative risk (RR) 2.5, 95% CI 1.2–5.3) and non-dipping of nocturnal SBP (RR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.7) at follow-up.

In another longitudinal study by Fernandez-Mendoza et al. (2021), persistent apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 2 or more since childhood was longitudinally associated with adolescent elevated BP (eBP) (odds ratio [OR], 2.9; 95%CI 1.1–7.5), while a remitted AHI of 2 or more was not (OR, 0.9; 95%CI 0.3–2.6). EBP is considered >90th percentile but less than the 95th percentile.97 Adolescent OSA was associated with eBP in a dose-response manner; however, the association of an AHI of 2 to less than 5 among adolescents was nonsignificant (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.9–2.6) and that of an AHI of 5 or more was approximately 2-fold (OR, 2.3; 95%CI, 1.1–4.9) after adjusting for visceral adipose tissue. An AHI of 5 or more (OR, 3.1; 95%CI, 1.2–8.5), but not between 2 and less than 5 (OR, 1.3; 95%CI, 0.6–3.0), was associated with orthostatic hyperreactivity among adolescents even after adjusting for visceral adipose tissue. Childhood OSA was not associated with adolescent eBP in female participants, while the risk of OSA and BP was greater in male participants.

The association between OSAS, decreased sleep duration and higher risk of hypertension is supported by data from other countries. In a retrospective cross-sectional study by Chuang et al. (2021), conducted in Taiwan, they investigated how obesity and OSAS severity affect BP in children.95 There was a trend of an increasing prevalence of hypertension in the children with more severe OSAS (p < 0.001), 20.9% and 38.2% in mild and severe OSAS group respectively. Furthermore, in the overall cohort, OSAS severity was found to be an independent predictor of pediatric hypertension. However, upon subgroup analysis, the effects of OSAS severity varied among patients with different weight status. In the non-obese children, OSAS severity was the only predictor of hypertension (OR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.17–4.05, p = 0.014). Whereas, among obese children, OSAS severity did not independently predict hypertension (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 0.65–3.92, p = 0.313).

In a cross-sectional study conducted by Bal et al. (2018), the researchers examine the association between blood pressure and the duration of sleep within primary and secondary schools in Turkey.98 Based on the results of the univariate binary logistic regression analyses, the study determined that having a sleep duration of less than 8 h is a notable risk factor for hypertension in both males and females. Furthermore, for both boys and girls, with each additional hour of sleep, the risk of elevated blood pressure decreased (OR:0.89, CI:0.82–0.98 for boys) and (OR:0.88, CI: 0.81–0.97 for girls). In multiple binary logistic regression analyses (adjusted for age and BMI), the analyses revealed that shorter sleep duration remained a risk factor for elevated blood pressure. The various causes of sleep disturbances, including obstructive sleep apnea, sleep fragmentation, and inadequate sleep duration, are key factors in pediatric hypertension (see Table 4 for definitions, impacts, and their link to hypertension).

The influence of socioeconomic and environmental factors on pediatric blood pressure

Socioeconomic factors may be another determinant of pediatric blood pressure and have been found to significantly impact pediatric blood pressure. East et al. (2020) showed that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds exhibited higher blood pressure levels compared to their peers from higher socioeconomic backgrounds.99 The researchers attributed this association to various factors, including limited access to healthcare services, unhealthy dietary habits, and increased exposure to psychosocial stressors.

Bal et al., also looked at various environmental conditions and their relationship to elevated blood pressure and found that living in urban as opposed to rural areas was as a risk factor for an increased risk of prehypertension and hypertension, OR: 1.43, CI: 1.11–1.84 for boys and OR: 1.77 CI:1.37–2.27 for girls (p < 0.05). There was no relationship between maternal employment, paternal education, house size, elevator use and mode of transport to school (p > 0.05).

Discussion of overall consequences of poor sleep

Although difficult to control, an issue worth highlighting is the different age ranges used to categorize adolescents. It is important to note that many of the studies conducted on adolescents generally do not utilize a standardized age range (Table 5). The range in ages has a significant impact because intrinsic factors like pubertal status seem to play a role in the development of hypertension. In addition, external factors such as schoolwork, extracurricular activities, home-life, electronic use can play a role in the adolescents’ sleep schedules and future studies should collect and examine this information as it could increase the power of these studies findings. The consequences of sleep insufficiency and disturbance are numerous, including a lack of higher-level cognitive skills, the development of which is critical during adolescence. Chronic sleep loss has been associated with increased alcohol and drug use.100 This observation however may be bidirectional as it has also been reported that alcohol consumption can lead to insufficient and poor-quality sleep.101 Sleep deprivation has also been associated with depressive moods. Sleep-deprived college students are reported to experience a higher risk of depressive symptoms,102 the same observation has been made in high school students.103 Additionally, several studies have linked sleep insufficiency to suicidal ideation. Adolescents who sleep less than 8 h at night are three times more likely to attempt suicide.104,105 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has established fresh consensus guidelines regarding the recommended amount of sleep essential for maintaining overall health, with a focus on preventing hypertension in children and adolescents.106 As per these guidelines, teenagers aged 13–18 should aim for 8–10 h of sleep within a 24-h period consistently to support their optimal health.

In conclusion, sleep plays an important role in the emotional and physical well-being within the pediatric population. As discussed above, fragmented or disrupted sleep causes a variety of clinical issues. An increased understanding more about the symptoms, causes, and implications of interrupted sleep can help us be informed about our situation and find the best treatments or preventative measures to minimize our sleep disturbances.

Future directions

The relationship between socioeconomic status, environmental factors, and sleep quality is crucial for future research. Exploring how elements such as housing conditions, neighborhood safety, and healthcare access affect children’s sleep and blood pressure can identify key intervention areas. Furthermore, understanding how sleep disturbances with and without OSA lead to pediatric hypertension is crucial for future research. Data from our laboratory have suggested that multiple factors and co-morbidities are associated with hypertension in pediatric patients without OSA.107 Utilizing advanced imaging, biomarkers, and longitudinal studies can clarify the involved pathophysiological pathways. Investigating the roles of inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and changes in the gut microbiome will help determine their effects on blood pressure regulation in children and adolescents. These efforts are crucial to addressing this growing public health concern and improving long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pena-Hernandez, C., Nugent, K. & Tuncel, M. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J. Prim. Care Community Health 11, 2150132720940519, https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720940519 (2020).

Bloomfield, D. & Park, A. Night time blood pressure dip. World J. Cardiol. 7, 373–376, https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v7.i7.373 (2015).

Flynn, J. T. et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 140 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1904 (2017).

Evans, J. M. et al. Body size predicts cardiac and vascular resistance effects on men’s and women’s blood pressure. Front Physiol. 8, 561, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00561 (2017).

Children, N. H. B. P. E. P. W. G. o. H. B. P. i. & Adolescents The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 114, 555–576, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.114.S2.555 (2004).

Zhang, T. et al. Trajectories of childhood blood pressure and adult left ventricular hypertrophy: The Bogalusa heart study. Hypertension 72, 93–101, https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10975 (2018).

Sinha, M. D. et al. Prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy in children and young people with primary hypertension: Meta-analysis and meta-regression. Front Cardiovasc Med 9, 993513, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.993513 (2022).

Gallibois, C. M., Jawa, N. A. & Noone, D. G. Hypertension in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease: management challenges. Int J. Nephrol. Renovasc Dis. 10, 205–213, https://doi.org/10.2147/IJNRD.S100891 (2017).

Warady, B. A. & Chadha, V. Chronic kidney disease in children: The global perspective. Pediatr. Nephrol. 22, 1999–2009, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0410-1 (2007).

Mitsnefes, M. et al. Masked hypertension associates with left ventricular hypertrophy in children with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 137–144, https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2009060609 (2010).

Wilson, D. K., Sica, D. A. & Miller, S. B. Ambulatory blood pressure nondipping status in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant black adolescents. Am. J. Hypertens. 12, 159–165, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00234-9 (1999).

Fabbian, F. et al. Dipper and non-dipper blood pressure 24-hour patterns: circadian rhythm-dependent physiologic and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Chronobiol. Int. 30, 17–30, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.715872 (2013).

Rahman, A., Hasan, A. U., Nishiyama, A. & Kobori, H. Altered circadian timing system-mediated non-dipping pattern of blood pressure and associated cardiovascular disorders in metabolic and kidney diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020400 (2018).

Bo, Y. et al. Short-term reproducibility of ambulatory blood pressure measurements: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 35 observational studies. J. Hypertens. 38, 2095–2109, https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000002522 (2020).

Hagenauer, M. H., Perryman, J. I., Lee, T. M. & Carskadon, M. A. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Dev. Neurosci. 31, 276–284, https://doi.org/10.1159/000216538 (2009).

Hinderliter, A. L. et al. Reproducibility of blood pressure dipping: Relation to day-to-day variability in sleep quality. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 7, 432–439, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2013.06.001 (2013).

Stergiou, G. S. et al. Reproducibility of home, ambulatory, and clinic blood pressure: implications for the design of trials for the assessment of antihypertensive drug efficacy. Am. J. Hypertens. 15, 101–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02324-x (2002).

Lehrer, H. M. et al. Blood pressure cuff inflation briefly increases female adolescents’ restlessness during sleep on the first but not second night of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Psychosom. Med 84, 828–835, https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000001098 (2022).

Judd, E. & Calhoun, D. A. Management of hypertension in CKD: Beyond the guidelines. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 22, 116–122, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2014.12.001 (2015).

Agarwal, R. & Light, R. P. The effect of measuring ambulatory blood pressure on nighttime sleep and daytime activity-implications for dipping. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 5, 281–285, https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.07011009 (2010).

Yilmaz, M. B. et al. Sleep quality among relatively younger patients with initial diagnosis of hypertension: dippers versus non-dippers. Blood Press 16, 101–105, https://doi.org/10.1080/08037050701343225 (2007).

Szyszka, M. et al. Circadian blood pressure profile in pediatric patients with primary hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11185325

Hausler, N. et al. Cardiovascular health and sleep disturbances in two population-based cohort studies. Heart 105, 1500–1506, https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314485 (2019).

Yang, L., Magnussen, C. G., Yang, L., Bovet, P. & Xi, B. Elevated blood pressure in childhood or adolescence and cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood: A systematic review. Hypertension 75, 948–955, https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.14168 (2020).

Lande, M. B. et al. Parental assessment of executive function and internalizing and externalizing behavior in primary hypertension after anti-hypertensive therapy. J. Pediatr. 157, 114–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.053 (2010).

Lande, M. B. et al. Neurocognitive function in children with primary hypertension after initiation of antihypertensive therapy. J. Pediatr. 195, 85–94 e81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.013 (2018).

Lucas, I. et al. Knowledge gaps and future directions in cognitive functions in children and adolescents with primary arterial hypertension: A systematic review. Front Cardiovasc Med 9, 973793, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.973793 (2022).

Galland, B. C., Taylor, B. J., Elder, D. E. & Herbison, P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: A systematic review of observational studies. Sleep. Med Rev. 16, 213–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2011.06.001 (2012).

Ohayon, M. M., Roberts, R. E., Zulley, J., Smirne, S. & Priest, R. G. Prevalence and patterns of problematic sleep among older adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 39, 1549–1556, https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200012000-00019 (2000).

Iglowstein, I., Jenni, O. G., Molinari, L. & Largo, R. H. Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: reference values and generational trends. Pediatrics 111, 302–307, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.2.302 (2003).

Cajochen, C., Kräuchi, K. & Wirz-Justice, A. Role of melatonin in the regulation of human circadian rhythms and sleep. J. Neuroendocrinol. 15, 432–437, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00989.x (2003).

Attanasio, A., Borrelli, P. & Gupta, D. Circadian rhythms in serum melatonin from infancy to adolescence. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 61, 388–390, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-61-2-388 (1985).

Commentz, J. C., Uhlig, H., Henke, A., Hellwege, H. H. & Willig, R. P. Melatonin and 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate excretion is inversely correlated with gonadal development in children. Horm. Res. 47, 97–101, https://doi.org/10.1159/000185442 (1997).

Iguchi, H., Kato, K. I. & Ibayashi, H. Melatonin serum levels and metabolic clearance rate in patients with liver cirrhosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 54, 1025–1027, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-54-5-1025 (1982).

Pruessner, J. C. et al. Free cortisol levels after awakening: A reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sci. 61, 2539–2549, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01008-4 (1997).

Watamura, S. E., Donzella, B., Kertes, D. A. & Gunnar, M. R. Developmental changes in baseline cortisol activity in early childhood: Relations with napping and effortful control. Dev. Psychobiol. 45, 125–133, https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20026 (2004).

Abe, K., Sasaki, H., Takebayashi, K., Fukui, S. & Nambu, H. The development of circadian rhythm of human body temperature. J. Interdiscip. Cycle Res. 9, 211–216, https://doi.org/10.1080/09291017809359638 (1978).

Kiess, W. et al. Salivary cortisol levels throughout childhood and adolescence: relation with age, pubertal stage, and weight. Pediatr. Res 37, 502–506, https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199504000-00020 (1995).

Glotzbach, S. F., Edgar, D. M., Boeddiker, M. & Ariagno, R. L. Biological rhythmicity in normal infants during the first 3 months of life. Pediatrics 94, 482–488 (1994).

Lodemore, M., Petersen, S. A. & Wailoo, M. P. Development of night time temperature rhythms over the first six months of life. Arch. Dis. Child 66, 521–524, https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.66.4.521 (1991).

Wailoo, M. P., Petersen, S. A., Whittaker, H. & Goodenough, P. Sleeping body temperatures in 3-4 month old infants. Arch. Dis. Child 64, 596–599, https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.64.4.596 (1989).

Andrade, M. M., Benedito-Silva, A. A. & Menna-Barreto, L. Correlations between morningness-eveningness character, sleep habits and temperature rhythm in adolescents. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res 25, 835–839 (1992).

Baehr, E. K., Revelle, W. & Eastman, C. I. Individual differences in the phase and amplitude of the human circadian temperature rhythm: With an emphasis on morningness-eveningness. J. Sleep. Res 9, 117–127, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00196.x (2000).

Carrier, J., Paquet, J., Morettini, J. & Touchette, E. Phase advance of sleep and temperature circadian rhythms in the middle years of life in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 320, 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00038-1 (2002).

Carreras, A. et al. Chronic sleep fragmentation induces endothelial dysfunction and structural vascular changes in mice. Sleep 37, 1817–1824, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4178 (2014).

Maki, K. A. et al. Sleep fragmentation increases blood pressure and is associated with alterations in the gut microbiome and fecal metabolome in rats. Physiol. Genomics 52, 280–292, https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00039.2020 (2020).

Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation 106, 3143–3421 (2002).

Redline, S. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing in adolescents. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176, 401–408, https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200703-375OC (2007).

Hagenauer, M. H., Ku, J. H. & Lee, T. M. Chronotype changes during puberty depend on gonadal hormones in the slow-developing rodent, Octodon degus. Horm. Behav. 60, 37–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.02.004 (2011).

Carskadon, M. A. in Sleep in children 125-144 (CRC Press, 2008).

Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C. & Jenni, O. G. Regulation of adolescent sleep: Implications for behavior. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1021, 276–291, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1308.032 (2004).

Crowley, S. J., Acebo, C., Fallone, G. & Carskadon, M. A. Estimating dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) phase in adolescents using summer or school-year sleep/wake schedules. Sleep 29, 1632–1641, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/29.12.1632 (2006).

Emmanuel, M. & Bokor, B. R. in StatPearls (2023).

Taylor, D. J., Jenni, O. G., Acebo, C. & Carskadon, M. A. Sleep tendency during extended wakefulness: Insights into adolescent sleep regulation and behavior. J. Sleep. Res 14, 239–244, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00467.x (2005).

Jenni, O. G., Achermann, P. & Carskadon, M. A. Homeostatic sleep regulation in adolescents. Sleep 28, 1446–1454, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/28.11.1446 (2005).

Roenneberg, T., Daan, S. & Merrow, M. The art of entrainment. J. Biol. Rhythms 18, 183–194, https://doi.org/10.1177/0748730403018003001 (2003).

Carskadon, M., Acebo, C. & Arnedt, J. in Sleep. A191-A191 (AMER ACAD SLEEP MEDICINE 6301 BANDEL RD, STE 101, ROCHESTER, MN 55901 USA).

Huang, Y. S., Wang, C. H. & Guilleminault, C. An epidemiologic study of sleep problems among adolescents in North Taiwan. Sleep. Med. 11, 1035–1042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.009 (2010).

Gariepy, G. et al. How are adolescents sleeping? adolescent sleep patterns and sociodemographic differences in 24 European and North American Countries. J. Adolesc. Health 66, S81–S88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.013 (2020).

Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep. Health 1, 40–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010 (2015).

Yang, C. K., Kim, J. K., Patel, S. R. & Lee, J. H. Age-related changes in sleep/wake patterns among Korean teenagers. Pediatrics 115, 250–256, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0815G (2005).

Roenneberg, T. et al. A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr. Biol. 14, R1038–R1039, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.039 (2004).

Owens, J. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: An update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics 134, e921–e932, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1696 (2014).

Patel, N. P., Grandner, M. A., Xie, D., Branas, C. C. & Gooneratne, N. “Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health 10, 475. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-475 (2010).

Spilsbury, J. C. et al. Sleep behavior in an urban US sample of school-aged children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 158, 988–994, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.10.988 (2004).

Marco, C. A., Wolfson, A. R., Sparling, M. & Azuaje, A. Family socioeconomic status and sleep patterns of young adolescents. Behav. Sleep. Med. 10, 70–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2012.636298 (2011).

Johnson, D. A., Billings, M. E. & Hale, L. Environmental determinants of insufficient sleep and sleep disorders: Implications for population health. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 5, 61–69, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-018-0139-y (2018).

Jones, M. N., Brown, C. M., Widener, M. J., Sucharew, H. J. & Beck, A. F. Area-level socioeconomic factors are associated with noncompletion of pediatric preventive services. J. Prim. Care Community Health 7, 143–148, https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131916632361 (2016).

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Kasen, S., First, M. B. & Brook, J. S. Association between television viewing and sleep problems during adolescence and early adulthood. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med 158, 562–568, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.6.562 (2004).

Calamaro, C. J., Mason, T. B. & Ratcliffe, S. J. Adolescents living the 24/7 lifestyle: effects of caffeine and technology on sleep duration and daytime functioning. Pediatrics 123, e1005–e1010, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3641 (2009).

Cain, N. & Gradisar, M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A review. Sleep. Med 11, 735–742, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.006 (2010).

Higuchi, S., Motohashi, Y., Liu, Y., Ahara, M. & Kaneko, Y. Effects of VDT tasks with a bright display at night on melatonin, core temperature, heart rate, and sleepiness. J. Appl Physiol. 94, 1773–1776, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00616.2002 (2003).

Boivin, D. B., Duffy, J. F., Kronauer, R. E. & Czeisler, C. A. Dose-response relationships for resetting of human circadian clock by light. Nature 379, 540–542, https://doi.org/10.1038/379540a0 (1996).

Zeitzer, J. M., Dijk, D. J., Kronauer, R., Brown, E. & Czeisler, C. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J Physiol 526 Pt 3, 695-702 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00695.x (2000).

Gubin, D. G. et al. Activity, sleep and ambient light have a different impact on circadian blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature rhythms. Chronobiol. Int. 34, 632–649, https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1288632 (2017).

Schäfer, A. & Kratky, K. W. The effect of colored illumination on heart rate variability. Forsch. Komplementmed 13, 167–173, https://doi.org/10.1159/000092644 (2006).

Rüger, M., Gordijn, M. C., Beersma, D. G., de Vries, B. & Daan, S. Time-of-day-dependent effects of bright light exposure on human psychophysiology: Comparison of daytime and nighttime exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 290, R1413–R1420, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00121.2005 (2006).

Obayashi, K., Saeki, K., Iwamoto, J., Ikada, Y. & Kurumatani, N. Association between light exposure at night and nighttime blood pressure in the elderly independent of nocturnal urinary melatonin excretion. Chronobiol. Int 31, 779–786, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2014.900501 (2014).

Xu, Y. X. et al. Physical activity alleviates negative effects of bedroom light pollution on blood pressure and hypertension in Chinese young adults. Environ. Pollut. 313, 120117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120117 (2022).

Bryant Ludden, A. & Wolfson, A. R. Understanding adolescent caffeine use: connecting use patterns with expectancies, reasons, and sleep. Health Educ. Behav. 37, 330–342, https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198109341783 (2010).

Orbeta, R. L., Overpeck, M. D., Ramcharran, D., Kogan, M. D. & Ledsky, R. High caffeine intake in adolescents: associations with difficulty sleeping and feeling tired in the morning. J. Adolesc. Health 38, 451–453, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.014 (2006).

Pollak, C. P. & Bright, D. Caffeine consumption and weekly sleep patterns in US seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-graders. Pediatrics 111, 42–46, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.42 (2003).

Roehrs, T. & Roth, T. Caffeine: sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep. Med Rev. 12, 153–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.004 (2008).

The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 114, 555-576 (2004).

Bucher, B. S. et al. Primary hypertension in childhood. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 15, 444–452, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-013-0378-8 (2013).

Hansen, M. L., Gunn, P. W. & Kaelber, D. C. Underdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents. JAMA298, 874–879, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.8.874 (2007).

Kapur, G. & Baracco, R. Evaluation of hypertension in children. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 15, 433–443, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-013-0371-2 (2013).

Norwood, V. F. Hypertension. Pediatr. Rev. 23, 197–208, https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.23-6-197 (2002).

Tu, W. et al. Intensified effect of adiposity on blood pressure in overweight and obese children. Hypertension 58, 818–824, https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.111.175695 (2011).

Javaheri, S., Storfer-Isser, A., Rosen, C. L. & Redline, S. Sleep quality and elevated blood pressure in adolescents. Circulation 118, 1034–1040, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.766410 (2008).

McCall, C. & McCall, W. V. Comparison of actigraphy with polysomnography and sleep logs in depressed insomniacs. J. Sleep. Res. 21, 122–127, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00917.x (2012).

Marcus, C. L., Greene, M. G. & Carroll, J. L. Blood pressure in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 157, 1098–1103, https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9704080 (1998).

Slowik, J. M., Sankari, A. & Collen, J. F. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2023).

Schwengel, D. A., Dalesio, N. M. & Stierer, T. L. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiol. Clin. 32, 237–261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2013.10.012 (2014).

Chuang, H. H. et al. Hypertension in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome-age, weight status, and disease severity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189602 (2021).

Chan, K. C., Au, C. T., Hui, L. L., Wing, Y. K. & Li, A. M. Childhood OSA is an independent determinant of blood pressure in adulthood: Longitudinal follow-up study. Thorax 75, 422–431, https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213692 (2020).

Fernandez-Mendoza, J. et al. Association of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea with elevated blood pressure and orthostatic hypertension in adolescence. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 1144–1151, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2003 (2021).

Bal, C. et al. The relationship between blood pressure and sleep duration in Turkish children: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Res Pediatr. Endocrinol. 10, 51–58, https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.4557 (2018).

East, P. et al. Childhood socioeconomic hardship, family conflict, and young adult hypertension: The Santiago Longitudinal Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 253, 112962, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112962 (2020).

Singleton, R. A. Jr. & Wolfson, A. R. Alcohol consumption, sleep, and academic performance among college students. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 70, 355–363, https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.355 (2009).

Mednick, S. C., Christakis, N. A. & Fowler, J. H. The spread of sleep loss influences drug use in adolescent social networks. PLoS One 5, e9775, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009775 (2010).

Regestein, Q. et al. Sleep debt and depression in female college students. Psychiatry Res 176, 34–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.006 (2010).

O’Brien, E. M. & Mindell, J. A. Sleep and risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Behav. Sleep. Med 3, 113–133, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_1 (2005).

Liu, X. Sleep and adolescent suicidal behavior. Sleep 27, 1351–1358, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/27.7.1351 (2004).

Liu, X. & Buysse, D. J. Sleep and youth suicidal behavior: A neglected field. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 19, 288–293, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000218600.40593.18 (2006).

Paruthi, S. et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: A consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep. Med 12, 785–786, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5866 (2016).

Exarchakis, A. et al. 0832 hypertension in pediatric patients without obstructive sleep apnea (OSA. Sleep 47, A356–A357, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsae067.0832 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lisa Price, MSLIS and Mohamed C. Shahenkari for their helpful comments and edits. This work was supported by NIH NHLBI LRP 1L40HL165612-01 to D.M.; NIH NHLBI LRP 2L40HL165612-02 to D.M.; Cooper Biomedical Sciences Internal Competitive Funds to D.M.; Spark Research Fellowship to A.E. and S.B.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Rowan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E., S.B. and D.M. performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. A.E., S.B., A.F. and D.M. provided scientific contribution to the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author (D.M.) attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Exarchakis, A., Bayo, S., Fink, A.M. et al. Inadequate sleep is a risk factor for pediatric hypertension: the pathophysiologic and socioeconomic correlates. Pediatr Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04199-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04199-3