Abstract

Study design

Registry-based cohort study.

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of the introduction of a new bladder management model of care at the Victorian Spinal Cord Service (VSCS) on the incidence of subsequent emergency department presentations and readmissions to hospital for urinary tract infection (UTI) in the first 2 years after injury.

Setting

VSCS, Austin Health, Melbourne, Australia.

Methods

A new model of care that prioritized intermittent self-catheterization was implemented at the VSCS on 1 August 2017. Data from the Victorian State Trauma Registry and Austin Health medical record were used to compare the rate of readmissions, emergency department (ED) presentations and hospitalisations for UTI in the first two years post-injury before and after practice was changed.

Results

A total of 333 cases were included; 149 cases pre-model of care change and 184 cases after. 143 males and 41 females with a mean (SD) age of 48.9 (19.7) were admitted to the VSCS following the change in model of care. The rate of any subsequent hospitalisation for UTI (ED presentation or admission) was lower following the introduction of the new bladder management model of care (Incidence rate ratio 0.30, 95% CI 0.12–0.73).

Conclusions

Our data demonstrates the real-world impact of a change in bladder management after new SCI. These data strengthen the consensus recommendation in current practice guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bladder and bowel care is often a time-consuming long-term challenge for a person living with a spinal cord injury (SCI) regardless of injury level [1]. People living with SCI frequently require bladder management strategies because of a neurogenic bladder. However, bladder management can cause complications such as urinary tract infections (UTI), a recurrent problem for up to 60% of people living with a SCI [2, 3] and 40% of these individuals report that UTIs have a moderate to severe impact on their life [2]. Patients are at risk of developing septicaemia due to a UTI and in the first year after injury the primary cause for emergency department (ED) admissions is septicemia, disorders of the urethra and urinary tract (primarily UTIs) [4, 5]. Urinary tract infections are the second most common cause of death in people living with SCI [6]. Better bladder and bowel function rates highly amongst health priorities for people living with SCI, while urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection (UTI) are among the most distressing complaints that impact quality of life (QoL) [7, 8]. A previous population-based study of 548 incident SCI cases admitted to Victorian hospitals found that 35% of people were readmitted to hospital for a SCI related condition in the first 2 years after injury [9]. Of the people readmitted, 26% involved a urological complication. The most common readmission reason was a UTI, with the total cost of UTI readmissions and ED visits exceeding $3.3 million Australian dollars over the two year period [9].

There are many methods for managing a neurogenic bladder. Two common options are the use of an indwelling catheter (IDC) and intermittent self-catherisation (ISC). An IDC is inserted into the bladder and can remain in situ for weeks at a time. ISC involves emptying the bladder at a specified, intermittent frequency by person inserting a catheter, completely draining the bladder and then removing the catheter [10, 11]. Whilst the evidence is low, some studies have found that ISC can reduce chronic urogenital complications such as UTI [12,13,14], and the European Association of Urology (EAU) and American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines recommend the use of ISC over IDC for bladder management [11, 15]. Intermittent self-catheterisation is therefore recommended as the gold standard of care for bladder management [11, 16,17,18]. The use of IDCs previously had been standard bladder care at the Victorian Spinal Cord Service (VSCS). A retrospective review of bladder management practice at the VSCS found that ISC was associated with a lower rate of UTI in people with SCI [16]. As such, in August 2017 the VSCS introduced a new method of bladder management, ISC. Therefore, the change in practice is important to reduce the risk and rate of UTI and improve QoL for people living with SCI. The aim of this project was to evaluate the impact of a new bladder management strategy following a change from using IDC as standard care to ISC.

Methods

Setting

The VSCS is the primary care centre for people with spinal cord injuries in Victoria, Australia.

Study design and participants

A registry-based cohort study of people with SCI managed before or after the introduction of the new model of bladder management care at the VSCS was conducted. Adult (>15 years) cases of traumatic SCI with a date of injury from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2020, and acute admission managed at the VSCS, were included. The research was conducted in compliance with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia’s 2023 National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID 78300) and the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID 29749). The research was conducted with approval of a waiver of consent as existing data were used.

Procedures

Eligible cases were identified using the VSTR, the State’s population-based registry for major trauma. Data extracted from the registry included demographic information, cause (transport, fall or other) and intent of injury (intentional, unintentional, intent cannot be determined), pre-existing conditions (Charlson Comorbidity Index), nature of the SCI, the Injury Severity Score (ISS), management in the State’s trauma system (managed at the VSCS or other trauma service, inter-hospital transfer status, intensive care unit admission status), in-hospital outcomes source of funding for the admission. Data related to readmission, hospitalization and ED presentation were extracted from the Austin Health electronic medical record (EMR).

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) is used to measure mortality risk and burden of disease [19, 20]. It can be used to prognosticate patient long-term mortality [20]. The quintile of socioeconomic status was measured by applying the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) to the patient’s postcode of residence. Range included 1 (most disadvantaged) to 5 (most advantaged) [21]. Remoteness of residence was assessed by applying the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) which classifies the patient’s postcode of residence into 1 of 5 categories including major city, inner regional, outer regional, remove and very remote [22]. These categories were consolidated into 2 categories; major cities, and inner regional, outer regional and remote. UTI was defined using the ICD-10-AM diagnosis code, N39.0, for the admission or ED presentation.

Management strategies of bladder care included IDCs that were changed every 6 weeks. They were changed earlier if they became blocked or the patient was diagnosed with a UTI. No antibiotics were administered prior to routine changes [15, 23].

Intermittent catheterisation was completed by either the nursing staff or patient while in hospital. If completed by nursing staff a sterile technique was performed however if a patient completed the IC a clean technique was used. No catheters were re-used. Patients had the option to utilise a self-contained unit [11].

The outcomes of interest for this study included:

-

i.

Readmission (yes/no) and number of readmissions to hospital for UTI in the first 2 years post-injury.

-

ii.

ED presentation (yes/no) and number of subsequent presentations to ED for UTI in the first 2 years post-injury.

-

iii.

Hospitalisation (yes/no) and number of hospitalisations (ED or readmission) for UTI in the first 2 years post-injury.

The outcome of “hospitalisation” included both subsequent ED presentations and hospital readmissions at the Austin. For all analyses, ED presentations excluded the cases of hospital readmission that were via an ED; ED presentations were only where the person was managed and directly discharged from the Austin ED.

Statistical analysis

For analysis, change in the ‘pre’ model of care commenced 1 August 2017 and ended on 30 April 2017 to remove any potential confounding from early cases, where the new model of care was piloted, between 1 May and 30 July 2017. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarise categorical variables. Median values and interquartile range (IQR) or means with standard deviation (SD) were used to describe continuous data. Baseline variables were compared between model of care groups using t tests if continuous data were normally distributed, Mann–Whitney u tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

The number of readmissions to hospital, and presentations to ED, for UTI in the first 2 years post-injury were modelled using a negative binomial model to allow for the overdispersion in the data. The model was adjusted for differences in the case-mix on acute admission and an indicator variable created to account for the small proportion of cases where a full 2 years of follow-up had not yet been reached (n = 16). Adjusted incidence ratios (IRR) along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. All analyses were performed using Stata Version 17. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Three hundred and fifty-eight eligible patients with SCI were registered on the VSTR from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2020. Fourteen people died during their acute hospital stay, and 11 people were admitted during the pilot testing phase for the new model of care. These 25 people were excluded, leaving 333 cases for analysis; 149 cases in the pre-model of care group and 184 cases in the post-model of care group (Fig. 1).

Individuals were predominantly male (77%), and the mean (SD) age was 48.3 (20.1) years. Demographic and baseline characteristics between the model of care groups are shown in Table 1. There was no association between demographic and SCI characteristics and care group except for the lower proportion of individuals receiving their definitive acute hospital care at the VSCS, and a higher ISS in the new model of care group (Table 1).

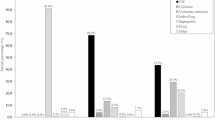

The proportion of individuals who experienced a subsequent ED presentation for UTI was lower in the new model of care phase while the prevalence of readmission and overall hospitalisation in the first 2 years after injury was not different (Table 2).

The rate of ED presentation was not significantly lower following the introduction of the new model of care (IRR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.08, 1.04, Fig. 2). The rate of readmission (IRR 0.21, 95% CI 0.12, 0.80), or any hospitalisation (IRR 0.3, 95% CI 0.12, 0.73), for UTI was lower following the introduction of the new bladder management model of care (Fig. 2). This reflects the lower number of repeat readmissions in the post phase (Table 2).

Discussion

This was the first study to compare the rate of ED presentations, admissions and hospitalisations after the transition from IDC as primary bladder management to ISC. In this study, the transition to ISC as the primary mode of bladder management was associated with lower rates of readmission and hospitalisation for UTI.

Re-hospitalisation rates for SCI have been demonstrated to be between 36–45% within the first-year post injury and approximately 30% for people with a chronic SCI (>1year) [4]. Of these 32% of presentations are associated with UTIs [4]. Our results are consistent with current literature recommending the use of ISC as gold standard bladder management [11, 16,17,18] to reduce the risk of UTIs and subsequent need for hospitalisation.

Despite the significant reduction in hospitalisations for UTI following implementation of a new model of bladder management, UTIs still occurred. Urinary tract infections remain one of the most common and distressing conditions for individuals living with a neurogenic bladder and have significant consequences for QoL and health outcomes [8, 14, 17, 24, 25]. Rates as low as 1–3 patient reported UTIs per year can significantly worsen QoL. Compared to individuals who have had no UTIs a patient’s odds of experiencing a worse quality of life increases as the rate of patient reported UTIs increases [25]. UTIs are the most common cause rehospitalisations in SCI [6]. Gabbe and Nunn (2016) found that UTI accounts for 61% of all ED costs for SCI. By reducing the number of ED presentations and subsequent hospitalisation it reduces the financial and resource burden on the healthcare system. Krause et al. [26] also found that the number of hospital bed days over the previous year was a significant predictor of increased mortality rates. Future work should focus how to reduce the number of UTIs for ISC and address potential factors impacting this rate.

A strength of this study was determining the effect implementing a new model of care had on the rate of ED presentations, admissions and hospitalisation. Previous studies have focused on the rate of UTIs in people using certain bladder management strategies [2, 17], or the rate of person reported UTIs [25], but observational studies of the impact of changing models of care are few. By understanding how a change in care impacts the hospital it helps to inform direction of care and resources. Nevertheless, there were limitations to this study. The study was observational before and after study and therefore only association and not causation could be inferred. Additionally this was a single site observational study, patients could have been admitted to hospitals other than the Austin for management of a UTI which would not have been captured in the data. Diagnosis of a UTI was made based on a patient’s presentation or admission being coded using the appropriate ICD-10-AM code. Previous data from the United States suggests this approach results in a high positive predictive value for diagnostic accuracy [27], although supporting data from Australia is not available. While ICD-10-AM coding is performed by trained coders in Australia, and there are robust audit processes for coding, our approach may have lead to over- or under-representation of the incidence of a UTI. While a randomised controlled trial (RCT) would have enabled assessment of causation, an RCT requires clinical equipoise as a foundation for justification. As there was already substantial evidence that ISC was the gold standard for clinical practice [11, 16,17,18], the justification for a clinical trial was low. ISC would not be indicated in all SCI people, though the case-mix between the phases was comparable, and a change in case-mix was unlikely to explain the findings.

The introduction of the new model of care for bladder management at the VSCS may have been associated with lower rates of ED presentation and hospitalization for UTI. A prospective study is required confirm these findings.

Data availability

Requests for access to data from the Victorian State Trauma Registry require approval from the data custodians, who can be contacted at susan.mclellan@monash.edu or at the following URL: http://www.med.monash.edu.au/assets/docs/sphpm/2016_nov_vstr_data_access_guidelines.pdf.

References

Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1371–83.

Biering-Sørensen F, Nielans H-M, Dørflinger T, Sørensen B. Urological situation five years after spinal cord injury. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1999;33:157–61.

Craven C, Hitzig SL, Mittmann N. Impact of impairment and secondary health conditions on health preference among Canadians with chronic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35:361–70.

DiPiro ND, Murday D, Corley EH, Krause JS. The primary and secondary causes of hospitalizations during the first five years after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2022;60:574–79.

Togan T, Azap OK, Durukan E, Arslan H. The prevalence, etiologic agents and risk factors for urinary tract infection among spinal cord injury patients. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2014;7:e8905.

Cardenas DD, Hoffman JM, Kirshblum S, McKinley W. Etiology and incidence of rehospitalization after traumatic spinal cord injury: a multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1757–63.

Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh J, Wolfe DL, Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence (SCIRE) Research Team. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1548–55.

Lee JS, Kim SW, Jee SH, Kim JC, Choi JB, Cho SY, et al. Factors affecting quality of life among spinal cord injury patients in Korea. Int Neurourol J. 2016;20:316.

Gabbe BJ, Nunn A. Profile and costs of secondary conditions resulting in emergency department presentations and readmission to hospital following traumatic spinal cord injury. Injury. 2016;47:1847–55.

Linsenmeyer T, Bodner D, Creasey G, Green B, Groah S, Joseph A, et al. Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health care providers. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:527–73.

EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Paris 2024. Arnhem, The Netherlands: EAU Guidelines Office; 2024.

Everaert K, Lumen N, Kerckhaert W, Willaert P, van Driel M. Urinary tract infections in spinal cord injury: prevention and treatment guidelines. Acta Clin Belg. 2009;64:335–40.

Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625–63.

Ryu KH, Kim YB, Yang SO, Lee JK, Jung TY. Results of urine culture and antimicrobial sensitivity tests according to the voiding method over 10 years in patients with spinal cord injury. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:345–9.

Ginsberg DA, Boone TB, Cameron AP, Gousse A, Kaufman MR, Keays E, et al. The AUA/SUFU guideline on adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: diagnosis and evaluation. J Urol. 2021;206:1097–105.

Hennessey DB, Kinnear N, MacLellan L, Byrne C, Gani J, Nunn AK. The effect of appropriate bladder management on urinary tract infection rate in patients with a new spinal cord injury: a prospective observational study. World J Urol. 2019;37:2183–8.

Kinnear N, Barnett D, O’Callaghan M, Horsell K, Gani J, Hennessey D. The impact of catheter‐based bladder drainage method on urinary tract infection risk in spinal cord injury and neurogenic bladder: a systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:854–62.

Denys P, Chartier-Kastler E, Even A, Joussain C. How to treat neurogenic bladder and sexual dysfunction after spinal cord lesion. Rev Neurologique. 2021;177:589–93.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson comorbidity index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91:8–35.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Index of Relative Socio‐Economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD). 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001Main+Features12016?OpenDocument.

Glover JD, Tennant SK. Remote areas statistical geography in Australia: notes on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA+ version): Public Health Information Development Unit, The University of Adelaide; 2003.

Geng V, Lurvink H, Pearce I, Vahr Lauridsen S. Catheterisation. Indwelling catheterisation in adults. Urethral and suprapubic. Evidence-based guidelines for best practice in urological health care. 2024. https://nurses.uroweb.org/guideline/indwellingcatheterisation-in-adults-urethral-and-suprapubic/.

Krebs J, Wöllner J, Pannek J. Risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infections in individuals with chronic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:682–6.

Theisen KM, Mann R, Roth JD, Pariser JJ, Stoffel JT, Lenherr SM, et al. Frequency of patient-reported UTIs is associated with poor quality of life after spinal cord injury: a prospective observational study. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:1274–81.

Krause JS, Carter RE, Pickelsimer EE, Wilson D. A prospective study of health and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1482–91.

Germanos G, Light P, Zoorob R, Salemi J, Khan F, Hansen M, et al. Validating use of electronic health data to identify patients with urinary tract infections in outpatient settings. Antibiotics. 2020;9:536.

Acknowledgements

Sue McLellan from the Victorian State Trauma Outcomes Registry and Monitoring (VSTORM) is sincerely thanked for their assistance with the project.

Funding

The project was funded by the Transport Accident Commission (TAC, Project ID T031). The Victorian State Trauma Registry (VSTR) is a Department of Health, State Government of Victoria and Transport Accident Commission funded project. BJG was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Investigator Grant (L2, ID2009998). Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BJG was responsible for the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. BJG also contributed data to the study. SRJH was responsible for interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. DJB was responsible for the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published. DJB also contributed data to the study. CM was responsible for interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. CM also contributed dat to the study. SR was responsible for conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. AN was responsible for conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. MG was responsible for interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. BM was responsible for design of the study, interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research was conducted in compliance with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia’s 2023 National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID 78300) and the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID 29749). The research was conducted with approval of a waiver of consent as existing data were used.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gabbe, B.J., Haughton, S.R., Nunn, A. et al. Evaluation of a new model of care for bladder management in a statewide spinal cord service. Spinal Cord 63, 189–193 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-024-01059-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-024-01059-5