Abstract

Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent mental illnesses in the contemporary world. Several animal models have been developed to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying these disorders and the effect of drugs in modulating the associated behavioral responses. Neuroinflammation has been related to mood disorders. Caffeine is a psychoactive substance that acts as a nonspecific blocker of adenosine receptors. Adenosine receptors are present in neurons and glial cells in different brain areas that are involved in controlling anxiety and depression. However, depending on the context, caffeine can exacerbate or inhibit neuroinflammation and behavioral responses associated with these conditions. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effects of caffeine and related xanthines on neuroinflammation observed in rodent models of anxiety and depression. A systematic database search (PROSPERO CRD42024517989) returned 17 eligible studies, separated based on the animal model. Most of the analyzed studies revealed that caffeine led to a beneficial effect, mitigating anxiety and depressive-like behaviors and possible cognitive impairments induced by stress. In addition, it also reversed oxidative damage and neuroinflammation by reducing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1ß, TNF-alpha, and IL-6 and inhibiting glial cell activation. Together, these data reveal a robust effect of caffeine in alleviating symptoms for individuals with these disorders, even though the doses and routes of caffeine administration were highly variable among eligible studies. In addition, they advance the identification of cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying these effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anxiety and depression have become the leading mental health challenges worldwide, affecting millions of people each year, with a substantial increase following the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. The economic burden and social cost of anxiety and depression affect several areas of people’s daily lives, with consequences for society [2, 3]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms in these conditions are complex and include neurochemical and structural changes in the brain, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and neuroinflammation, among others [4,5,6].

The pharmacological limitations to treating the overwhelming set of symptoms affecting patients with anxiety and depression have opened avenues to search for natural compounds and nutritional strategies [7]. Although caffeine has multifaceted effects on psychiatric disorders, in recent years, the action of caffeine has become a target of investigations in different pathological contexts, including mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, with potentially beneficial outcomes [8,9,10].

Caffeine is present in various beverages and foods that are part of our daily lives, such as coffee, tea, energy drinks, soft drinks, and chocolate, making it one of the most consumed substances in the world [11]. Caffeine belongs to the xanthine group and acts as a nonspecific antagonist of adenosine receptors, mainly A1 and A2A [12]. Other mechanisms of action are also known, such as the inhibition of phosphodiesterase, mobilization of intracellular calcium, and the antagonism of GABAa receptors at toxic levels of caffeine [13]. The blockage of adenosine receptors directly affects the release of neurotransmitters, modulating the GABAergic, glutamatergic, dopaminergic, and serotonergic systems [11, 14,15,16]. Besides, adenosine receptors are often found in oligomeric complexes with different receptors [17]. A2A-CB1 heteromers in the corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals appear relevant for treating neuropsychiatric disorders [18]. The interaction of A2A-D2 receptors in the prefrontal cortex and the mesocorticolimbic system shows that activation of A2A receptors decreases dopaminergic activity, contributing to inhibiting motivational behaviors. Thus, several studies demonstrate that inhibitors of A2A receptors, such as caffeine and theophylline, positively affect effort-related motivational aspects [8, 19, 20], which are also observed with selective A2A receptor antagonists [8, 20, 21]. These effects appear to be mediated by dopaminergic signaling, which is usually inhibited by A2A receptor activation. Additionally, caffeine exhibits antioxidant properties and immunomodulatory potential, making it an important target for anti-inflammatory effects [22, 23].

In this context, the effect of caffeine is still controversial since time, dose, and exposure period can be highly variable in clinical and preclinical studies [15, 24]. Here, we conducted a systematic review of animal studies to gather information on the effects of caffeine and related xanthines on neuroinflammation, particularly in conditions of anxiety and depression.

Methods

This systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO—registration number CRD42024517989) and conducted under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement.

Search strategy

A search was conducted on the Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com), PubMed (https://PubMed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and Science Direct (https://www.sciencedirect.com) electronic databases between May 1st and 6th, 2024. The search was rerun on November 8th, 2024, using the same criteria. The search strategy terms and URL are available in the supplementary material. We applied filters in the English language and animal species when available. The period of publication was not limited. The PECO strategy was: (1) population: animal models of anxiety and depression; (2) exposure: in vivo treatment with caffeine or related xanthine; (3) comparison: control groups submitted to a similar manipulation except for the absence of caffeine or related xanthine; (4) Outcomes: anxiety or depressive-like behavior and neuroinflammation.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: Original articles carried out on rodents of both sexes; Studies using acute, sub-chronic, or chronic caffeine/xanthines exposure protocol; Studies with caffeine/xanthines exposure at any development period from prenatal to adult; Studies with caffeine/xanthine administration through any route (oral, intraperitoneal, intravenous, subcutaneous, or intracerebral); Studies using control or wild-type animals at the same experimental conditions and biological characteristics; and Studies with data on inflammation mediators, neuroinflammation, lymphocytes, macrophages, microglia, astrocytes, inflammatory markers, neuroimmunological mechanism, and immune cell counting.

On the other hand, exclusion criteria were studies with non-vertebrate animals and non-rodents; in vitro or in silico studies; studies without a control group; no mention of neuroinflammatory analysis; not peer-reviewed; abstracts of articles from scientific congress; review of literature; Dissertation or Thesis. In studies where caffeine or other xanthines were administered in combination with other substances, all experimental groups that received drug combinations were excluded from the analysis. Only experimental groups that used exclusively caffeine or isolated xanthines and their respective control groups were included to evaluate the specific effects of these substances on the parameters investigated. Moreover, studies were also included that combined caffeine and other bioactive compounds found in coffee, green tea, other beverages, food, and medicine.

Screening process

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the screening process. The reports retrieved from all databases had duplicated references excluded. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, three reviewers (LSN, GVRMM, and YON) manually screened the titles and abstracts to assess the studies’ eligibility. These analyses were carried out independently, and each researcher’s decisions were blinded to the other. Two senior researchers (RSS and PCC) performed a final revision, resolving any potential divergences. Those reports inaccessible in scientific databases were sought by contacting the corresponding authors when their contact details were available.

Campello-Costa, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/o80f263.

The present systematic review included 17 studies. We downloaded the full text of eligible studies and assessed them for data extraction. We also evaluated the references of the selected articles to identify possible additional articles of interest.

Data extraction

Three reviewers (LSN, GVRMM, and YON) performed data extraction manually and independently and then constructed a consensus table. The main data extracted were: 1) authors; 2) specific animal strain and sex; 3) model of human disease (anxiety or depression); 4) age; 5) period of caffeine exposure; 6) caffeine concentration or dosage; 7) route of caffeine administration; 8) type of behavioral evaluation; 9) biochemical analysis; 10) main results; 11) main conclusions.

Assessment of risk of bias

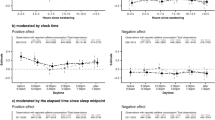

The SYRCLE tool was applied to estimate the risk of bias from individual studies [25]. The tool consists of 10 questions to assess bias based on the study design, the number of animals, the type of control, blinding, and randomization of the process, the analysis of the results, and the quality of outcome assessment, among others. Studies were rated as ‘low’ or ‘high’ risk of bias. When the data for each question was not clearly described in the text, they were classified as “unclear”. Three researchers evaluated the risk of bias in eligible studies manually and independently and reached a consensus. Figure 2 summarizes the percentage of articles at risk of bias for each parameter gathered by the animal model of anxiety or depression.

Data synthesis and analysis

Considering that classifying psychiatric diseases in animal models is challenging, we grouped the eligible studies according to the behavioral and neurobiological variables described by the authors. Data were grouped as best as possible according to the experimental modeling of anxiety or depression, and the quality of the evidence was considered.

Results

Selection process

The literature search identified 3114 unique articles. After reviewing the title and abstract, 530 studies were selected for full-text screening. Ultimately, 17 articles that met the above-mentioned inclusion criteria were included for data extraction (Fig. 1). Based on the neurobiological mechanisms and behavioral responses described by the authors, six studies focused on animal models of anxiety, and eleven addressed models of depression.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias for each eligible study was assessed using the SYRCLE tool and is summarized in Fig. 2. For the anxiety models, 5 out of 6 studies defined the methods used to generate the sequence, and all reported the baseline characteristics. Only one study hid the allocation method. No study explained whether the distribution of groups and the analysis of results were done blindly, so we considered a high risk of bias. Only one study reported that animal breeders and/or researchers were blinded to the experimental groups. All studies reported complete results. Regarding animal models of depression, 7 out of 11 studies described the methods used to generate the sequence, and 9 out of 11 reported the baseline characteristics. However, two studies hid the allocation method. Most studies did not mention whether group allocation and analysis of results were random and blinded. Eight out of nine studies did not report incomplete and selective outcomes. However, the bias of selective outcome reporting was considered unclear in one study.

Effects of caffeine and caffeine-related compounds in animal models of anxiety

Models of anxiety were established using various protocols: some studies have induced acute stress, while others have performed chronic stress (Table 1). The acute stress models include animal selection after behavior response at elevated plus maze (EPM) [26], sleep deprivation for 48 h [27], and psychological stress with exposure of rodents to the odor of cat urine [28]. In chronic stress models, chronic variable psychological stress [28], restraint stress [29], and caffeine consumption [30, 31] were applied in the eligible studies (Fig. 3). In all selected studies, male adult rats were used, Wistar [26, 29, 31] and Sprague Dawley [27, 28], except for one study that used adolescent albino rats [30].

Different acute and chronic protocol stress induction was selected. Different behavior tests evaluated anxiety, depression, and cognitive functions. In acute stress, there was an increase in pro-inflammatory (interleukin 6 - IL-6; interleukin ß1 - IL1-ß, and TNF-alpha) and a decrease in anti-inflammatory (interleukin 4 - IL-4; interleukin 10 - IL10) cytokines and BDNF. At the cellular level, activation of astrocytes and microglia, neuronal damage, and neutrophil infiltration in the brain were also demonstrated. Oxidative stress was observed with increased lipid peroxidation, as measured by malondialdehyde (MDA), nitric oxide (NO), superoxide radical formation, and a decrease in glutathione (GSH) content. In chronic stress, there was an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6; TNF-alpha, IL1-ß) in glucose levels and acetylcholinesterase (AChE). The level of oxidative stress markers was decreased (catalase, Glutathione S-Transferase – GST, Glutathione Peroxidase – GPx, TAC - Total Antioxidant Capacity) as well as the level of serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, and norepinephrine (NORE). Neuronal damage was also observed. In all articles selected for this review, caffeine treatment, directly or indirectly, reversed the behavioral, cellular, and molecular changes described in the models. Created in BioRender. Campello-Costa, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/o80f263.

In the acute stress protocol, caffeine was administered in 1 [28] or 2 days [26, 27] with a dose varying from 3 mg.kg-1ip. [28], 50 mg.kg-1 sc [26], or 60 mg.kg-1 via gavage [27]. In the chronic stress studies, caffeine was administered chronically but with variation in time of exposure in two [28], three [29], four [30], or six weeks [31]. The dose of caffeine varied between 0.3 g. L-1 [29], 0.84 mg.kg1 [31], 30 mg.kg-1 [30]. The route of exposure varied among oral gavage [22, 23, 27, 31], subcutaneous [26], intraperitoneal [28, 30], and oral in the bottle [29].

Caffeine treatment is effective in reversing anxiety-like behaviors in almost all eligible studies and can reverse cellular and molecular changes induced by stress. In acute stress, caffeine exposure leads to anxiolytic effects in the elevated plus maze, open field test [27], and hole-board test [28]. It also improves memory in the object recognition test (ORT) [28]. Additionally, it exhibits an anti-inflammatory action, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-alpha, and IL-1β, while increasing IL-10 and IL-4 in the brain and plasma, and decreasing microglial reactivity [27]. Besides, it decreases myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA), which reflects a decrease in lipid peroxidation [28]. Also, it decreases NO levels and SOD activity while improving glutathione and luminol levels [28]. On the other hand, animals selected after behavioral response in the elevated plus maze (EPM) were divided into three groups based on the time spent in the open arm of the EPM. Acute caffeine injection increases corticosterone levels and leads to anxiogenic behavior in animals with high anxiety, indicating that the effects of caffeine depend on individual characteristics [26].

The beneficial effects of caffeine were also observed in the chronic stress protocol [28, 29]. In chronic variable psychological and physical restraint stress, anxiolytic effects were observed in EPM [29], OFT [29], and HBT [28]. Antidepressant effects were observed in SPT [29], FST [29], and HPT [28], while a memory improvement was described in Y-maze [29], ODT [29], and ORT evaluations [28]. These behavioral changes induced by caffeine were accompanied by a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-1ß, as well as in the P2X7R and A2a adenosine receptors [29]. Additionally, caffeine down-regulated P2X7R and A2A receptors [29], increased dopamine in the cortex and hippocampus, decreased GABA in the hippocampus [30], and induced neuroprotection [31]. Some eligible studies have demonstrated the action of caffeine on glial cells through changes in GFAP and Iba-1 expression in stress-specific brain areas [27, 29]. The anti-inflammatory and anxiolytic effects of caffeine were also demonstrated by a reduction in oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation [26, 28, 30, 31]. Chronic treatment with caffeine was also beneficial for adolescent rats, decreasing anxiety in the DLB and successive alleys test (SAT) and increasing dopamine in the cortex and hippocampus [30]. Mingori and colleagues compared the effect of caffeine with guarana extract in middle-aged rats, finding that only caffeine produced an anxiolytic effect and improved memory, an effect associated with neuroprotection in the hippocampus and striatum [31].

Effects of caffeine and caffeine-related compounds in animal models of depression

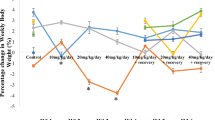

Table 2 summarizes the main features of the selected studies. To induce depressive-like behavior, 5 out of 11 of the studies used an inflammatory depression induction protocol through the intraperitoneal administration of LPS (lipopolysaccharide) [32,33,34,35,36] (Table 2) with LPS doses ranging from [36], 0.5 mg.kg-1 [35], 0.83 mg.kg-1 [32, 33, 36], and 1.5 mg.kg-1 [34]. Other studies have induced depressive behavior through sleep deprivation protocols [37, 38], chronic water immersion restraint stress [39], reactivity model conjugated to social stress [40], and chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) [41, 42] (Fig. 4).

Among the main models of depression are inflammatory depression induced by LPS injection, social defeat stress, chronic water immersion restraint stress, and paradoxical sleep deprivation (PSD). Different behavior tests, including forced swim, tail suspension test, exploratory activity in the open field, and sucrose preference test confirm all these phenotypes. These protocols have been associated with neuroinflammation measured by the increase in cytokines levels, such as gamma-interferon (IFNγ), interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin ß1 (IL1-ß), and TNF-alpha, increased microglial activation, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) content, and phosphorylation of NFKß (pNFKß), expression of Npas4 and Lcn2 and indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity. Also, the neopterin/biopterin ratio is increased. In all eligible articles, caffeine treatment, directly or indirectly, reversed the behavioral changes observed in the models and neuroinflammation markers. Furthermore, caffeine increases hippocampal neurogenesis in adults, and antioxidant agents like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH) decrease lipid peroxidation. In one study using the PSD model, a high dose of caffeine was harmful, leading to depressive and anxiogenic effects and memory impairment. Created in BioRender. Campello-Costa, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/o80f263.

Classical behavior tests confirmed depressive behavior like forced swim test (FST) [32,33,34, 36, 38,39,40, 42], tail suspension test (TST) [32,33,34, 36, 38, 39], sucrose preference test (SPT) [35, 38,39,40, 42], and exploratory activity in the open field test (OFT) [32,33,34, 36, 38, 40]. Also, anxiety-like behavior was measured in the EPM [37, 40], DLB [34, 42], OFT [34], and hole board test (HBT) [37], and memory in the object recognition test (ORT) [42].

In these depression models, caffeine exposure was mostly chronic [32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 41, 42], except for one study with acute exposure [40]. Furthermore, administered caffeine doses varied significantly across the studies: 5 mg.kg-1 [34], 10 mg.kg-1 [32, 33, 39], 12.5 mg.kg1 [42], 20 mg.kg1 [39], 25 or 50 mg.kg1 [42], 60 mg.kg-1 [39], and 200 mg.kg-1 [37]. Some studies have evaluated the effect of co-administration of caffeine with other substances, such as caffeic acid at 15 mg.kg-1 or 10 mg.kg-1 [34], coffee and decaffeinated coffee at 140 mg.kg-1 each [32], instant coffee powder at 0.5 ml/100 g and decaffeinated coffee at 200 mg.kg-1 [38], and green tea [35]. Furthermore, one study did not administer caffeine directly to animals but instead assessed its effects by transplanting cells pretreated with caffeine (100 μg per 15 × 106 cells) in vitro [40].

Caffeine was administered through gavage in 9 out of 11 of the studies [32,33,34, 36,37,38,39, 41, 42], orally in 1 out of 11 cases [35], and indirectly through cell culture treatment in 1 out of 11 works [40]. In all studies evaluated, adult male animals were used, with slight variations between species, with 6 out 11 of individuals being mice as Swiss [34], C57BL/6 J [32, 33, 40], SAMP10/TaIdrSlc [35], and Kunming [39], and 3 out of 11 of animals being Wistar [37, 38, 42] and two Sprague-Dawley [36, 41] rats.

Regardless of the animal model, all studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of caffeine with antidepressant and anti-inflammatory actions. In the inflammatory depression models, a mild to moderate chronic consumption of caffeine reversed the LPS-induced depressive behaviors in the OFT, in the FST, and the TST [32,33,34, 36]. Also, caffeine decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-1ß, IFNγ [33] and AKT and TNF-alpha phosphorylation [36] and lipid peroxidation [33, 34] induced by LPS and increases BDNF levels [33]. Interestingly, these effects closely resembled those of imipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant drug [32, 33]. In another study, caffeine’s anti-depressant and anti-inflammatory effects were comparable to those of caffeinated coffee but were not observed with decaffeinated coffee [32]. On the other hand, caffeine and decaffeinated coffee lead to anti-inflammatory effects, as evidenced by a reduction of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity, a lower neopterin-to-biopterin ratio, and in the brain concentrations of PGE2, key inflammatory markers associated with depression [32]. Mudgal and coworkers demonstrated that in Swiss mice treated with LPS, a one-week treatment with a low dose of caffeine and a low dose of caffeic acid produced anxiolytic effects in the OFT and DLB, antidepressant effects in OFT and DLB, and anti-inflammatory effects with reduction of IL-6 and TNF-alpha in serum and brain [34]. Similarly, it was shown that daily consumption of green tea may offer protective benefits against LPS-induced inflammatory depression, leading to anti-depressant behavior in the SPT and reduction in the transcriptional factors Npas, Lcn2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines - TNF-alpha, IL-1ß [35].

Considering the sleep deprivation depression protocol (PSD), both conventional coffee (CC) and decaffeinated coffee (DC) decreased depressive behavior in the TST, FST, SPT, and OFT, and the levels of TNF-alpha. However, the level of IL-6 is reduced only with CC [38]. On the other hand, in another study of PSD, a high dose of caffeine impairs memory and leads to an anxiogenic and depressive-like behavior in the hole board and elevated plus maze tests, and social interaction and locomotor activity, respectively, also increased pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 [37].

In a stress-induced depression protocol, caffeine administered at two different doses for a month also protected mice against depressive-like behavior in the TST, FST, and SPT and increased serotonin. At the same time, it decreases 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) levels. Additionally, caffeine reduced CD68 and IBA-1, markers associated with microglia activation in the hippocampus, and decreased inflammatory markers, including nitric oxide (NO), IL-1ß, TNF-alpha, and NFkB [39].

In a social defeat protocol, transplantation of immune cells pre-treated with caffeine in vitro reversed depressive behavior in FST, OFT, SPT, and anxiety in EPM. These mice also exhibited decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-1ß, IL-6, and INF-γ and increased anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10, and IL-4. They also presented increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurogenesis, and/or survival of CA1 and CA3 hippocampal neurons [40].

Interestingly, Chen and coworkers demonstrated, in chronic unpredictable mild stress protocol, the beneficial effects of chaingun granules, which lead to neuroprotection through the reduction of xanthine’s content and ROS, antidepressant effects observed in SPT, FST, OFT and EPM and anti-inflammatory response by inhibiting the xanthine—P2X7R-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and decreasing TNF-alpha, IL-1ß; IL-6, MDA, and increase SOD [41].

In some articles eligible for analysis, other biochemical parameters usually altered in animal models of depression were also evaluated. Caffeine prevented lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by increased MDA levels [33, 34, 42], increased antioxidant factors such as SOD and glutathione peroxidase – (GSH) [34, 38, 42], reduced acetylcholinesterase activity [37], increased BDNF levels [33, 40] and neurogenesis by reducing p-MEK/MEK, p-ERK1/2/ERK 1/2 e p-NFkB/GPADH ratios [39, 40], neuroprotection measured by KA/3-HK and KA/KYN ratios [32] and restore gut microbiota balance [38]. Additionally, caffeine decreased serum corticosterone levels, reduced acetylcholinesterase content, and increased monoamine levels in the brain [42]. Besides, green tea inhibits adrenal hypertrophy and thymic atrophy induced by LPS-induced depression [35].

Discussion

The World Health Organization points out that anxiety and depression are the most prevalent mental diseases in the world [1]. Although anxiety and depression are complex disorders with diverse biological and psychological characteristics, animal models can replicate certain aspects of these conditions, including neurochemical mechanisms, with repercussions on social and cognitive domains, providing a valuable framework for testing new therapeutic strategies [43, 44]. This review analyzed the effects of caffeine, mainly in a scenario of neuroinflammation in animal models of anxiety and depression. In general, eligible studies have pointed to common and primarily positive effects of caffeine in reducing behaviors and neuroinflammation associated with anxiety and depression in adult male rodents.

Animal strains and models

The studies selected for animal models of anxiety and depression were diverse in terms of the animals used. Sixteen out of seventeen eligible studies were performed in adult male animals, except for one study in the anxiety model, which used adolescents [27]. This homogeneity of age and sex facilitates the comparison of results. However, it leaves a gap in the literature regarding the effects on females, who appear to be differentially affected by stress stimuli [45, 46]. Indeed, caffeine intake leads to cellular and behavioral sex-dependent effects [47,48,49,50,51]. Furthermore, considering the high prevalence of depression among the elderly and the potential beneficial effects of coffee consumption for this group [52], it becomes relevant to investigate the impact of caffeine on neuroinflammation associated with mood disorders during aging.

Anxiety models were developed in rats [26,27,28,29,30,31], while depression models were performed in mice [32,33,34,35, 39, 40] or rats [36,37,38, 41, 42]. The diversity of strains used is also important, as mice and rats presented differences in vulnerability to stressful stimuli and behavior [53].

In general, in animal models, anxiety and depression are induced by different stressor stimuli applied acutely or chronically. Consequently, biochemical imbalances in the central nervous system and changes in behavior are observed. Following acute stress, an increase in adenosine release triggers an adaptive response aimed at restoring homeostasis, mainly by activating A1 receptors that promote an inhibitory control of neuronal hyperexcitability [54]. Additionally, A2A receptors can participate in the control of synaptic plasticity, which will contribute to behavioral adjustments [55, 56]. On the other hand, chronic stress promotes a maladaptive shift in adenosine receptors, characterized by the downregulation of A1 receptors and the upregulation of A2A receptors in hippocampal glutamatergic terminals [57, 58]. Thus, sustained activation of the A2A receptor leads to the activation of microglia, contributing to neuroinflammation [59, 60]. In this context, caffeine [61] or a selective A2AR antagonist [62] reduces the neuroinflammatory response and attenuates behavioral changes triggered by stress [63,64,65]. Also, acute LPS intraperitoneal injection is a classical model of inflammatory depression, while chronic paradoxical sleep deprivation (PSD) may induce or not neuroinflammation [66, 67]. So, the experimental conditions are crucial to the individual outcomes. Behavioral changes are measured in tests that allow predictive assessment in specific contexts. Despite the differences among animal strains and stressful stimuli, all eligible studies confirm phenotypes using classical behavioral tests to assess anxiety (EPM, DLB, and OFT) and depression-like behaviors (TST, FST, SPT, and OFT). Other specific tests were used, such as the SAT [42] to investigate social interaction and the multivariate concentric square field (MCSF) [26] to evaluate emotional and cognitive characteristics. Since anxiety and depression usually impact memory systems, some studies also analyze Y-maze [29, 42] and ORT [29, 31, 42] (Figs. 3, 4). It is well established that caffeine and specific A2AR antagonist reverse synaptic and memory impairment in helpless mice [51] and in mice subjected to chronic unpredictable stress [58]. However, subjective experiences, which are relevant components of depressive symptoms in patients, remain a challenge in animal studies. Herein, we did not identify studies that correlated effort-related motivational aspects, such as those assessed by the Effort-Based Decision-Making and Learned Helplessness tests, in animal models of anxiety or depression subjected to exposure to caffeine and related xanthines, while also evaluating inflammatory parameters.

Effects of caffeine administration

Caffeine is the most consumed psychoactive substance, producing different effects depending on the dose/concentration, time (acute or chronic), route, and stage of life during exposure [12]. In non-toxic doses, the effects of caffeine are mediated by differential antagonism of A1 and A2A adenosine receptors. Blockade of the A1 receptor is involved in hippocampal synaptic facilitation, while blockade of the A2A receptor impacts hippocampal plasticity [68].

These receptors exhibit distinct spatial expression profiles across brain regions and show developmental stage-dependent distribution. Acute caffeine administration preferentially antagonizes A1 receptors, whereas repeated exposure primarily inhibits A2A receptor signaling, resulting in distinct adaptive mechanisms [12, 69, 70]. Additionally, a recent study revealed that caffeinated coffee enhances A1 receptor density and function in the ventral, but not the dorsal, hippocampus of rats, suggesting that it is involved in processing mood-related information. Besides, a similar result was demonstrated in striatal preparations, which are closely associated with the processing of anhedonia and motivational behaviors [51]. This is in accordance with recent reports showing that habitual coffee consumption modifies brain functional connectivity with potential implications for emotional regulation and affective processing [71, 72].

In the selected studies, caffeine was delivered directly via oral gavage in most cases (10 out of 14). One study used oral treatment in drinking water [29], one used subcutaneous [26], and two used intraperitoneal injections [28, 30]. This difference impacts the pharmacokinetics and availability of caffeine [73], as well as the direct comparison of the results. Caffeine was administered chronically in doses ranging from 5 to 200 mg.kg-1 in the oral gavage treatment. Caffeine doses of 5 to 50 mg.kg-1 led to low levels of caffeine in the plasma, like those found in regular consumption in humans [12]. It is well described that caffeine generates a more significant state of alertness and cognitive improvement through the antagonism of adenosine receptors [74]. Interestingly, depending on the context, mild anxiogenic effects can be observed [75]. This is in line with an eligible study by Lind and colleagues that showed that caffeine at 50 mg.kg-1 was anxiogenic only for high-anxiety groups previously selected in EPM [26]. However, 200 mg.kg-1 of caffeine in rodents represents high and toxic doses with prolonged exposure time for the individual [12]. In this case, the deleterious effects of caffeine, such as hyperactivity, anxiogenic behaviors, and neurotoxicity, can be observed. In addition, Daubry and colleagues demonstrated anxiogenic and inflammatory effects with 200 mg.kg-1 of caffeine in sleep-deprivation rats [37]. A systematic review and meta-analysis in humans described that a high dose of caffeine, equivalent to approximately 5 cups of coffee (400-750 mg), can trigger and exacerbate panic attacks in adults [9]. So, there is substantial evidence in the literature indicating that high doses of caffeine induce anxiety-related behaviors in both human and animal studies [76].

The impact of caffeine on the neuroimmune system has been studied as a possible mechanism underlying its positive effect on central nervous system diseases [77]. Peripheral and central inflammation have been implicated in psychiatric disorders [78]. Inflammatory markers are increased in patients with depression and anxiety, mainly in those who are refractory to conventional treatments [79, 80]. Neuroinflammation disrupts neurotransmitter systems such as glutamate and dopamine, contributing to symptoms like anhedonia and impairing motivational circuits, which are classically involved in depressive disorders [81]. This is supported by studies showing that anti-inflammatory intervention reduces depressive symptoms [82].

Different eligible studies demonstrated that caffeine intake down-regulated the pro- and up-regulated the anti-inflammatory cytokines altered by stress [27, 83]. Other beneficial effects of caffeine observed in the present systematic review include its antioxidant properties, which have been demonstrated in some selected studies. These effects are extremely important since they adjust redox status and ameliorate inflammatory processes, improving human health. This effect is also dose-dependent [84]. The main players in neuroinflammation are astrocytes and microglial cells. In fact, their activation with a pro-inflammatory phenotype has been consistently observed in several animal models of anxiety and depression [85,86,87,88,89]. These glial cells express adenosine receptors and are susceptible to the effects of caffeine [90]. Caffeine inhibited corticosterone-induced microglial activation in the context of stress-induced depression [39], suggesting that this compound may have an antidepressant effect associated with the modulation of glial cells. The ability of caffeine to reduce microglial reactivity involves antagonism of the A2A receptor [59, 60, 77]. Another study demonstrated that caffeine reduces NLRP3 inflammasome activation by inducing autophagy in microglia [91], suggesting a potential mechanism for investigation in the context of mood disorders.

Curiously, pre-treating immune cells with caffeine and subsequently transplanting them into mice subjected to social defeat stress also produced antidepressant and anti-inflammatory effects, and an increase in hippocampal neurogenesis, suggesting a substantial and positive association between caffeine and related processes [40]. However, another study failed to detect any impact of caffeine on neurogenesis in depressed mice [92].

Additionally, acute caffeine treatment suppresses phagocytosis in human mononuclear phagocytes, thereby promoting an anti-inflammatory response [93]. Rodas and colleagues demonstrated that regular low caffeine consumption induced a slight anti-inflammatory effect in healthy populations. They suggested that further studies should be performed to determine the coffee intake required to observe more significant health effects [94].

In addition to caffeine’s role in the inflammatory context with beneficial effects, such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions, it is important to highlight that other mechanisms of action of caffeine have been associated with its ability to control psychiatric disorders. Caffeine, through A1 and A2A receptor antagonism, is involved in the control of synaptic transmission and plasticity, which may be related to its neuroprotective effect [95]. Indeed, caffeine modulates the release of neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF, in both physiological and pathological contexts, providing relief against depressive-like behaviors [33, 96]. Besides, caffeine acting through neuronal A2A receptors prevents synaptic changes and mood dysfunction induced by chronic stress in mice [58]. Chronic caffeine consumption also promotes metabolic changes [97]. In recent work, Lopes and colleagues demonstrated that caffeine increased the energy charge and redox state of cortical synaptosomes, suggesting that this effect led to an increase in the glycolytic rate, thereby enhancing astrocyte-synapse lactate transport. This metabolic enhancement in synapses may improve brain function [98]. This metabolic increase may also contribute to strengthening the glymphatic system, which is also controlled by the A2A adenosine receptor [99]. It has been demonstrated that in sleep deprivation, this system is impaired, promoting an accumulation of neurotoxic residues in areas related to mood disorders, such as the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala [100, 101]. Also, glymphatic impairment could induce oxidative stress and inflammation, contributing to depressive disorders [102]. Although caffeine consumption may impact sleep and thus impair glymphatic flow, some positive effects may be observed in chronic caffeine users due to metabolic improvements. Therefore, it is essential to explore the therapeutic potential of caffeine through other forms besides its participation in the inflammatory context.

Caffeine-related substances

Some of the studies on depressive models analyzed other compounds besides caffeine. In low doses, caffeic acid, when combined with caffeine, exhibits anxiolytic, antidepressant, and anti-inflammatory effects by reducing LPS-induced depressive-like behavior and decreasing TNF-alpha and IL-6 levels [34]. This is consistent with other reports that caffeic acid has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may help reverse behaviors associated with depression. [103, 104]. Other studies reported here that caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee have a similar effect, inhibiting depression-like behaviors and inflammatory pathways [32, 38]. These results contrast with findings that showed both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee improved the antioxidant status in the mice’s frontal cortex, although only caffeinated coffee improved mood and welfare in both male and female mice [51]. Corroborating, Lucas and colleagues showed that the risk of depression in adult women decreases with increasing consumption of caffeinated coffee, but not with decaffeinated coffee [105]. Likewise, a more recent study reported that daily consumption of 2 to 3 cups of coffee containing caffeine, regardless of additives, reduced the risk of anxiety and depression in both sexes. The authors suggest that moderate caffeinated consumption may be recommended as part of a healthy lifestyle to improve mental health. Once again, decaffeinated coffee showed no effect [106].

Also, green tea intake was beneficial in LPS-induced inflammatory depression. The analysis of green tea content reveals that the major components are caffeine (C), epigallocatechin gallate (E), theanine (T), and arginine (A). The CE/TA ratio of 4-5 improves depressed mood, while neuroinflammation and adrenal hypertrophy are suppressed with a CE/TA ratio of 2 - 8 [35]. Altogether, these findings support the idea that not only caffeine, but also other related components play a significant role in ameliorating behavioral and inflammatory parameters in anxiety and depression-like contexts.

Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effects of caffeine and related xanthines on neuroinflammation in rodent models of anxiety and depression. Overall, the findings are consistent with the anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of caffeine and are well correlated with its anti-inflammatory actions (Figs. 3 and 4). Thus, caffeine and related compounds emerge as promising natural molecules for future nutritional strategies that may help as adjuvants to the limited treatments not only for mood disorders, especially anxiety and depression, but also for other neurological conditions associated with neuroinflammatory processes.

Limitations

It is essential to consider that this systematic review has some limitations. (1) Lack of female rodents studies; (2) Heterogeneity in animal strains, caffeine exposure, and protocols for pathology induction; (3) Only articles in English were selected; (4) The studies were carried out mainly on adult animals, making it impossible to discuss the use of caffeine during critical periods of brain development, such as adolescence, or even in pregnant or lactating females, for example; (5) Lack of studies in elderly animals since depression is very common at this stage of life, and caffeine appears to have several beneficial effects, including on inflammatory processes; (6) The molecular markers evaluated were different, which makes direct comparison of results difficult.

Despite the challenges in grouping and comparing data due to the methodological diversity of the eligible studies mentioned above, the convergence of results supports the robustness of caffeine´s beneficial effects in reducing inflammatory or oxidative responses following stressful stimuli in adult male animals.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders#:~:text=In%202019%2C%201%20in%20every,of%20the%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic (accessed 19 January 2025).

Ghosh PA, Chaudhury S, Rohatgi S. Assessment of depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life, and fatigue in patients after a cerebrovascular accident. Cureus. 2024;16:e72051. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.72051

Kupferberg A, Hasler G. The social cost of depression: investigating the impact of impaired social emotion regulation, social cognition, and interpersonal behavior on social functioning. J. Affect Disord. 2023;14:100631 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2023.

Guo B, Zhang M, Hao W, Wang Y, Zhang T, Liu C. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02297-y

Martin EI, Ressler KJ, Binder E, Nemeroff CB. The neurobiology of anxiety disorders: brain imaging, genetics, and psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychiat Clin North Am. 2009;32:549–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.05.004

Trifu SC, Trifu AC, Aluas E, Tataru MA, Costea RV. Brain changes in depression. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61:361–70. https://doi.org/10.47162/rjme.61.2.06

Del Portillo MM, Clemente-Suárez VJ, Ruisoto P, Jimenez M, Ramos-Campo DJ, Beltran-Velasco AI, et al. Nutritional modulation of the gut-brain axis: a comprehensive review of dietary interventions in depression and anxiety management. Metabolites. 2024;14:549. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14100549

López-Cruz L, Salamone JD, Correa M. Caffeine and selective adenosine receptor antagonists as new therapeutic tools for the motivational symptoms of depression. Front Pharm. 2018;9:526. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00526

Klevebrant L, Frick A. Effects of caffeine on anxiety and panic attacks in patients with panic disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hospital Psychiat. 2022;74:22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.11.005

Meamar M, Raise-Abdullahi P, Rashidy-Pour A, Raeis-Abdollahi E. Coffee and mental disorders: how caffeine affects anxiety and depression. Prog Brain Res. 2024;288:115–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2024.06.015

McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR. A review of caffeine’s effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;71:294–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001

Fredholm BB, Battig K, Holmén J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE. Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:83–133.

Reddy VS, Shiva S, Manikantan S, Ramakrishna S. Pharmacology of caffeine and its effects on the human body. Eur J Med Chem Rep. 2024;10:100138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmcr.2024.100138

Alasmari F. Caffeine induces neurobehavioral effects through modulating neurotransmitters. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28:445–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.02.005

Fiani B, Zhu L, Musch BL, Briceno S, Andel R, Sadeq N, et al. The neurophysiology of caffeine as a central nervous system stimulant and the resultant effects on cognitive function. Cureus. 2021;13:e15032. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.15032

Khaliq S, Haider S, Naqvi F, Perveen T, Saleem S, Haleem DJ. Altered brain serotonergic neurotransmission following caffeine withdrawal produces behavioral deficits in rats. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2012;25:21–25.

Franco R, Cordomí A, Del Torrent CL, Lillo A, Serrano-Marín J, Navarro G, et al. Structure and function of adenosine receptor heteromers. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:3957–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-021-03761-6.Epub

Martire A, Tebano T, Chiodi V, Ferreira G, Cunha RA, Köfalvi A, et al. Pre-synaptic adenosine A2A receptors control cannabinoid CB1 receptor-mediated inhibition of striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission. J Neurochem. 2011;116:273–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07101.x

Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar AM, Nunes EJ, Pardo M. Dopamine, behavioral economics, and effort. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;7:13. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.08.013.2009

SanMiguel N, Pardo M, Carratalá-Ros C, López-Cruz L, Salamone JD, Correa M. Individual differences in the energizing effects of caffeine on effort-based decision-making tests in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2018;169:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2018.04.004

Nunes EJ, Randall PA, Santerre JL, Given AB, Sager TN, Correa M. Differential effects of selective adenosine antagonists on the effort-related impairments induced by dopamine D1 and D2 antagonism. Neuroscience. 2010;170:268–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.068

Horrigan LA, Kelly JP, Connor TJ. Immunomodulatory effects of caffeine: friend or foe?. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:877–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.02.002

Rodak K, Kokot I, Kratz EM. Caffeine as a factor influencing the functioning of the human body-friend or foe?. Nutrients. 2021;13:3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093088

Temple JL, Bernard C, Lipshultz SE, Czachor JD, Westphal JA, Mestre MA. The Safety of ingested caffeine: a comprehensive review. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:80. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00080

Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-43

Lind FS, Stam F, Zelleroth S, Meurling E, Frick A, Grönbladh A. Acute caffeine differently affects risk-taking and the expression of BDNF and of adenosine and opioid receptors in rats with high or low anxiety-like behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;227-228:173573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2023.173573

Wadhwa M, Chauhan G, Roy K, Sahu S, Deep S, Jain V, et al. Caffeine and modafinil ameliorate the neuroinflammation and anxious behavior in rats during sleep deprivation by inhibiting the microglia activation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:49. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2018.0004

Cakir OK, Ellek N, Salehin N, Hamamcı R, Keleş H, Kayalı DG, et al. Protective effect of low dose caffeine on psychological stress and cognitive function. Physiol Behav. 2017;168:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.10.010

Dias L, Lopes CR, Gonçalves FQ, Nunes A, Pochmann D, Machado NJ, et al. Crosstalk between ATP-P2X7 and adenosine A2A receptors controlling neuroinflammation in rats subject to repeated restraint stress. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:639322. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2021.639322

Sabry FM, Masoud MA, Georgy GS. Caffeine affects the neurobehavioral impact of sodium benzoate in adolescent rats. Neurosci Let. 2024;832:137801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2024.137801

Mingori MR, Heimfarth L, Ferreira CF, Gomes HM, Moresco KS, Delgado J, et al. Effect of paullinia cupana mart. commercial extract during the aging of middle age wistar rats: differential effects on the hippocampus and striatum. Neurochem Res. 2017;42:2257–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-017-2238-4

Hall S, Arora D, Anoopkumar-Dukie S, Grant GD. Effect of coffee in lipopolysaccharide-induced indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase activation and depressive-like behavior in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:8745–54. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03568

Mallik SB, Mudgal J, Hall S, Kinra M, Grant GD, Nampoothiri M, et al. Remedial effects of caffeine against depressive- like behaviour in mice by modulation of neuroinflammation and BDNF. Nut Neurosci. 2022;25:1836–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2021.1906393

Mudgal J, Mallika SB, Nampoothiria M, Kinra M, Hall S, Grant GD, et al. Effect of coffee constituents, caffeine and caffeic acid on anxiety and lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behavior in mice. J Funct Foods. 2020;64:103638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2019.103638

Unno K, Furushima D, Tanaka Y, Tominaga T, Nakamura H, Yamada, et al. Improvement of depressed mood with green tea intake. Nutrients. 2022;14:2949. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142949

Zhang R, Zhang L, Du W, Tang J, Yang L, Geng D, et al. Caffeine alleviate lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation and depression through regulating p-AKT and NF-κB. Neurosci Lett. 2024;837:137923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2024.137923

Daubry TME, Nwogueze BC, Toloyai PEY, Moke EG. Alcohol and caffeine Co-administration increased acetylcholinesterase activity and inflammatory cytokines in sleep-deprived rats: implications for cognitive decline and depressive-like manifestations. Sleep Sci. 2024;17:e90–e98. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1778013

Gu X, Zhang S, Ma W, Wang Q, Li Y, Xia C, et al. The impact of instant coffee and decaffeinated coffee on the gut microbiota and depression-like behaviors of sleep-deprived rats. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:778512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.778512

Mao ZF, Ouyang SH, Zhang QY, Wu YP, Wang GE, Tu LF, et al. New insights into the effects of caffeine on adult hippocampal neurogenesis in stressed mice: inhibition of CORT-induced microglia activation. FASEB J. 2020;34:10998–1014. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202000146RR

Markovaa EV, Knyazhevaa MA, Tikhonovab MA, Amstislavskaya TG. Structural and functional characteristics of the hippocampus in depressive-like recipients after transplantation of in vitro caffeine-modulated immune cells. Neurosci Lett. 2022;786:136790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136790

Chen J, Li T, Huang D, Gong W, Tian J, Gao X, et al. Integrating UHPLC-MS/MS quantitative analysis and exogenous purine supplementation to elucidate the antidepressant mechanism of Chaigui granules by regulating purine metabolism. J Pharm Anal. 2023;13:1562e1576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2023.08.008

Okeowo OM, Oke OO, David GO, Ijomone OM. Caffeine administration mitigates chronic stress-induced behavioral deficits, neurochemical alterations, and glial disruptions in rats. Brain Sci. 2023;13:1663. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121663

Gencturk S, Unal G. Rodent tests of depression and anxiety: construct validity and translational relevance. Cog Aff Behav Neurosci. 2024;24:191–224. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-024-01171-2

Petković A, Chaudhury D. Encore: behavioural animal models of stress, depression and mood disorders. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:931–64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.931964

Lin Y, Horst GJT, Wichmann R, Bakker P, Liu A, Li X, et al. Sex differences in the effects of acute and chronic stress and recovery after long-term stress on stress-related brain regions of rats. Cereb Cortex. 2008;19:1978–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn225

Mir FR, Rivarola MA. Sex differences in anxiety and depression: what can (and cannot) preclinical studies tell us?. Sexes. 2022;3:141–63. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes3010012

De Souza LL, Meyer LG, Rossetti CL, Miranda RA, Bertasso IM, Lima DGV, et al. Maternal low-dose caffeine intake during the perinatal period promotes short- and long-term sex-dependent hormonal and behavior changes in the offspring. Lif Sci. 2024;354:122971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122971

Oliveira BS, Paula TMD, Cardoso LC, Ferreira JVL, Machado CA, Fernandes HB, et al. Caffeine intake during gestation and lactation causes long-term behavioral impairments in heterogenic mice offspring in a sex-dependent manner. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2025;247:173949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2024.173949

Sallaberry C, Ardais AP, Rocha A, Borges MF, Fioreze GT, Mioranzza S, et al. Sex differences in the effects of pre- and postnatal caffeine exposure on behavior and synaptic proteins in pubescent rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;81:416–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.015

Teixeira-Silva B, Mattos GVRM, Carvalho VF, Campello-Costa P. Caffeine intake during lactation has a sex-dependent effect on the hippocampal excitatory/inhibitory balance and pups’ behavior. Brain Res. 2025;1846:149247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2024.149247

Machado NJ, Ardais AP, Nunes A, Szabó EC, Silveirinha V, Silva HB, et al. Impact of coffee intake on measures of wellbeing in mice. Nutrients. 2024;16:2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172920

Lopes CR, Cunha RA. Impact of coffee intake on human aging: epidemiology and cellular mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;102:102581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102581

Acikgoz B, Dalkiran B, Dayi A. An overview of the currency and usefulness of behavioral tests used from past to present to assess anxiety, social behavior and depression in rats and mice. Behav Process. 2022;200:104670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2022.104670

Dunwiddie TV, Masino S. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31

Cunha RA. Different cellular sources and different roles of adenosine: A1 receptor-mediated inhibition through astrocytic-driven volume transmission and synapse-restricted A2A receptor-mediated facilitation of plasticity. Neurochem Int Jan. 2008;52:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.026

Yamada K, Kobayashi M, Kanda T. Involvement of adenosine A2A receptors in depression and anxiety. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2014;119:373–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801022-8.00015-5

Cunha GMA, Canas PM, Oliveira CR, Cunha RA. Increased density and synapto-protective effect of adenosine A2A receptors upon sub-chronic restraint stress. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1775–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.024

Kaster MP, Machado NJ, Silva HB, Nunes A, Ardais AP, Santana M, et al. Caffeine acts through neuronal adenosine A2A receptors to prevent mood and memory dysfunction triggered by chronic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:7833–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1423088112

Rebola N, Simões AP, Canas PM, Tomé AR, Andrade GM, Barry CE, et al. Adenosine A2A receptors control neuroinflammation and consequent hippocampal neuronal dysfunction. J Neurochem. 2011;117:100–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07178.x

Du H, Li CH, Gao RB, Tan Y, Wang B, Peng Y, et al. Inhibition of the interaction between microglial adenosine 2A receptor and NLRP3 inflammasome attenuates neuroinflammation posttraumatic brain injury. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30:e14408. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.14408

Boia R, Elvas F, Madeira M, Aires ID, Rodrigues-Neves AC, Tralhão P, et al. Treatment with A2A receptor antagonist KW6002 and caffeine intake regulate microglia reactivity and protect retina against transient ischemic damage. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3065. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2017.451

Simões AP, Duarte JA, Agasse F, Canas PM, Tomé AR, Agostinho P, et al. Blockade of adenosine A2A receptors prevents interleukin-1β-induced exacerbation of neuronal toxicity through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:204. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-9-204

van Calker D, Biber K, Domschke K, Serchov T. The role of adenosine receptors in mood and anxiety disorders. J Neurochem. 2019;151:11–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.14841

Pasquini S, Contri C, Merighi S, Gessi S, Borea PA, Varani K, et al. Adenosine receptors in neuropsychiatric disorders: fine regulators of neurotransmission and potential therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031219

Bevilacqua, LM, Neto, FS, Kaster, MP. Adenosine A2A signaling in mood disorders: how far have we come?, IBRO Neuroscience Reports 2024. 0 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibneur.2024.08.006

Mahalakshmi AM, Lokesh P, Hediyal TA, Kalyan M, Vichitra C, Essa MM, et al. Impact of sleep deprivation on major neuroinflammatory signal transduction pathways. Sleep Vigil. 2022;6:101–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-022-00203-6

Tufik S, Andersen ML, Bittencourt LRA, de Mello MT. Paradoxical sleep deprivation: neurochemical, hormonal and behavioral alterations. evidence from 30 years of research. Acad Bras Ciênc. 2009;81:521–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0001-37652009000300016

Lopes JP, Pliássova A, Cunha RA. The physiological effects of caffeine on synaptic transmission and plasticity in the mouse hippocampus selectively depend on adenosine A1 and A2A receptors. Biochem Pharm. 2019;166:313–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2019.06.008

Costenla AR, Cunha RA, de Mendonça A. Caffeine, adenosine receptors, and synaptic plasticity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S25–34. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-091384

Ferre S, Ciruela F, Borycz J, Solinas M, Quarta D, Antoniou K, et al. Adenosine A1-A2A receptor heteromers: new targets for caffeine in the brain. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2391–9. https://doi.org/10.2741/2852

Picó-Pérez M, Magalhães R, Esteves M, Vieira R, Castanho TC, Amorim L, et al. Coffee consumption decreases the connectivity of the posterior Default Mode Network (DMN) at rest. Front Behav Neurosci. 2023;28:1176382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1176382

Magalhães R, Picó-Pérez M, Esteves M, Vieira R, Castanho TC, Amorim L, et al. Habitual coffee drinkers display a distinct pattern of brain functional connectivity. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:6589–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01075-4

Arnaud MJ. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of natural methylxanthines in animal and man. Handbook Exp Pharm. 2011;200:33–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13443-2_3

Nehlig A. Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:S85–94. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2010-091315

Lara DR. Caffeine, mental health, and psychiatric disorders. Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:S239–48. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-1378

Yacoubi ME, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Costentin J, Vaugeois JM. The anxiogenic-like effect of caffeine in two experimental procedures measuring anxiety in the mouse is not shared by selective A(2A) adenosine receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;148:153–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002130050037

Madeira MH, Boia R, Ambrósio AF, Santiago AR. Having a coffee break: the impact of caffeine consumption on microglia-mediated inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Med Inflamm. 2017;2017:4761081. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4761081

Corrigan M, O’Rourke AM, Moran B, Fletcher JM, Harkin A. Inflammation in the pathogenesis of depression: a disorder of neuroimmune origin. Neuronal Signal. 2023;13:NS20220054. https://doi.org/10.1042/NS20220054

Haroon E, Daguanno AW, Woolwine BJ, Goldsmith DR, Baer WM, Wommack EC, et al. Antidepressant treatment resistance is associated with increased inflammatory markers in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;95:43–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.026

Miller, AH, Lucido, M.j., Bekhbat, M, Mehta, ND, Chen, X, Treadway, MT, et al. Inflammation and treatment resistance: mechanisms and treatment implications. Managing Treatment-Resistant Depression in Road to Novel Therapeutics 2022 237-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824067-0.00015-3

Lucido MJ, Bekhbat M, Goldsmith DR, Treadway MT, Haroon E, Felger JC, et al. Aiding and Abetting Anhedonia: Impact of Inflammation on the Brain and Pharmacological Implications. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:1084–117. https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000043

Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:22–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2015.5

Othman MA, Fadel R, Tayem Y, Jaradat A, Rashid A, Fatima A, et al. Caffeine protects against hippocampal alterations in type 2 diabetic rats via modulation of gliosis, inflammation and apoptosis. Cell Tiss Res. 2022;392:443–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-022-03735-5

Barcelos RP, Lima FD, Carvalho NR, Bresciani G, Royes LFF. Caffeine effects on systemic metabolism, oxidative-inflammatory pathways, and exercise performance. Nut Res. 2020;80:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2020.05.005

Wang YL, Han QQ, Gong WQ, Pan DH, Wang LZ, Hu W, et al. Microglial activation mediates chronic mild stress-induced depressive- and anxiety-like behavior in adult rats. J Neuroinflammation Jan 17. 2018;15:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1054-3

Hao T, Du X, Yang S, Zhang Y, Liang F. Astrocytes-induced neuronal inhibition contributes to depressive-like behaviors during chronic stress. Life Sci. 2020;258:118099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118099

Aten S, Du Y, Taylor O, Dye C, Collins K, Thomas M, et al. Chronic stress impairs the structure and function of astrocyte networks in an animal model of depression. Neurochem Res. 2023;48:1191–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-022-03663-4

Novakovic MM, Korshunov KS, Grant RA, Martin ME, Valencia HA, Budinger GRS, et al. Astrocyte reactivity and inflammation-induced depression-like behaviors are regulated by Orai1 calcium channels. Nat Commun. 2023;14:5500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40968-6

Cangul Yurtdas H, Zortul H, Yilmaz B, Aricioglu F. Microglial activation mediates maternal separation-induced depressive-like behavior in rats: a neurodevelopmental depression model. Journal Affect Disord Rep. 2023;12:100462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100462

Daré E, Schulte G, Karovic O, Hammarberg C, Fredholm BB. Modulation of glial cell functions by adenosine receptors. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.031

Wang HQ, Song KY, Feng JZ, Huang SY, Guo XM, Zhang L, et al. Caffeine inhibits activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via autophagy to attenuate microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Mol Neurosci. 2022;72:97–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-021-01894-8

Machado NJ, Simões AP, Silva HB, Ardais AP, Kaster MP, Garção P, et al. Caffeine reverts memory but not mood impairment in a depression-prone mouse strain with Up-regulated adenosine A2A receptor in hippocampal glutamate synapses. Mol Neurobiol Mar. 2017;54:1552–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-9774-9

Steck RP, Hill SL, Weagel EG, Weber KS, Robison RA, O’Neill KL. Pharmacologic immunosuppression of mononuclear phagocyte phagocytosis by caffeine. Pharmacol Res Persp. 2015;3:e00180. https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.180

Rodas L, Riera-Sampol A, Aguilo A, Martínez S, Tauler P. Effects of habitual caffeine intake, physical activity levels, and sedentary behavior on the inflammatory status in a healthy population. Nutrients. 2020;12:2325. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082325

Cunha RA. How does adenosine control neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration?. J Neurochem. 2016;139:1019–55.

Lao-Peregrín C, Ballesteros JJ, Fernández M, Zamora-Moratalla A, Saavedra A, Gómez Lázaro M, et al. Caffeine-mediated BDNF release regulates long-term synaptic plasticity through activation of IRS2 signaling. Addict Biol. 2017;22:1706–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12433

Paiva I, Cellai L, Mériaux C, Poncelet L, Nebie O, Saliou J-M, et al. Caffeine intake exerts dual genome-wide effects on hippocampal metabolism and learning-dependent transcription. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e149371. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI149371

Lopes CR, Oliveira A, Gaspar I, Rodrigues MS, Santos J, Szabó E, et al. Effects of chronic caffeine consumption on synaptic function, metabolism and adenosine modulation in different brain areas. Biomolecules. 2023;13:106. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010106

Sun X, Dias L, Peng C, Zhang Z, Ge H, Wang Z, et al. 40 Hz light flickering facilitates the glymphatic flow via adenosine signaling in mice. Cell Discov. 2024;10:81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-024-00701-z

Que M, Li Y, Wang X, Zhan G, Luo X, Zhou Z. Role of astrocytes in sleep deprivation: accomplices, resisters, or bystanders?. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1188306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2023.1188306

Palagini L, Geoffroy PA, Miniati M, Perugi G, Biggio G, Marazziti D. Insomnia, sleep loss, and circadian sleep disturbances in mood disorders: a pathway toward neurodegeneration and neuroprogression? a theoretical review. Psychol Med. 2022;27:298–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720003996.

Gu S, Li Y, Jiang Y, Huang JH, Wang F. Glymphatic dysfunction induced oxidative stress and neuro-inflammation in major depression disorders. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:2296. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11112296

Jalali A, Firouzabadi N, Zarshenas MM. Pharmacogenetic-based management of depression: Role of traditional Persian medicine. Phytot Res. 2021;35:5031–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7134

Westfall S, Caracci F, Zhao D, Wu QL, Frolinger T, Simon J, et al. Microbiota metabolites modulate the T helper 17 to regulatory T cell (Th17/Treg) imbalance promoting resilience to stress-induced anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors. Brain Behav Imm. 2021;91:350–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.10.013

Lucas M, Mirzaei F, Pan A, Okereke OI, Willett WC, O’reilly ÉJ, et al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of depression among women. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1571–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.393

Min Y, Yang H, Wang X, Xu C. The association between coffee consumption and risk of incident depression and anxiety: exploring the benefits of moderate intake. Psychiatry Res. 2023;326:115307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115307

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/Brazil), Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ/Brazil), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES/Brazil). Laís da Silva Neves and Yasmin Oliveira de Nazareth are recipients of a CAPES fellowship (Finance Code 001). Giovanna Varzea Roberti Monteiro de Mattos received the CNPq fellowships (141314/2024-9). Rosane Souza da Silva is a Research Awardee of the CNPq (Finance Code 307825/2022-1). Paula Campello-Costa is a Research Career Awardee of the CNPq (Finance Code 316573/2021-3) and from FAPERJ (E-26/200341/2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PCC conceived of the presented idea, performed the final revision, and administered the whole project. LSN, GVRMM, YON, and RSS performed the literature search. LSN, GVRMM, and YON screened and selected the studies based on pre-established criteria. PCC and RSS performed the final revision, resolving potential divergences. PCC and RSS designed, elaborated, and made all figures. LSN wrote the original draft. All authors discussed the research, contributed to the final manuscript, and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva Neves, L., de Mattos, G.V.R.M., Oliveira-Nazareth, Y. et al. Effects of caffeine on neuroinflammation in anxiety and depression: a systematic review of rodent studies. Transl Psychiatry 15, 477 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03668-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03668-x