Abstract

In the decade since FDA approval of the first-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib, the treatment landscape for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has transformed. Targeted agents, as monotherapy or in combination regimens, have decisively replaced chemoimmunotherapy as the standard of care. In national CLL guidelines updated from 2023 through 2025 – including those from France, Germany, and the US – chemoimmunotherapy is considered a treatment option in only exceptional cases, reflecting broad consensus among experts that targeted therapies should be used universally in the management of previously untreated CLL. The primary first-line treatment options for CLL comprise continuous therapies based on the BTK inhibitors ibrutinib, zanubrutinib, or acalabrutinib, or fixed-duration regimens combining the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax with obinutuzumab or the BTK inhibitors ibrutinib or acalabrutinib (with or without obinutuzumab). Selecting the appropriate targeted therapy requires careful evaluation of a multitude of factors, including molecular disease features (especially del[17p]/TP53 and IGHV mutational status), comorbidities, comedications, and the patient’s preferences. Focusing on primary treatment options, we review data from the key controlled trials that support the first-line use of targeted therapies for patients with CLL, consider ongoing trials that may support clinical decision-making in the future, and assess the potential to personalize treatment regimens in CLL based on minimal residual disease status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The treatment landscape for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has changed dramatically since FDA approval of the first-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib for CLL in 2014. In the subsequent decade, targeted therapies have supplanted the role of chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as preferred first-line therapy. In national guidelines from 2023 to 2025, recommended treatments for previously untreated CLL comprise continuous therapy with the selective BTK inhibitors acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, or fixed-duration regimens combining the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax with obinutuzumab or the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib [1,2,3]. Following approval in some regions, venetoclax combinations with acalabrutinib (with or without obinutuzumab) are expected to be incorporated into treatment guidelines where authorized.

BTK and BCL2 inhibitor–based regimens provide durable responses with manageable safety profiles for most patients [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, in the absence of head-to-head data comparing continuous BTK inhibitor–based regimens with fixed-duration venetoclax-based regimens, physicians face a challenge in selecting between these options to optimize first-line treatment outcomes for each patient.

Focusing on the first-line setting, where all approved therapies are viable options for many patients with CLL, we review important clinical trial data with continuous BTK inhibitor therapy, venetoclax-obinutuzumab (Ven-Obi), ibrutinib-venetoclax (Ibr-Ven), and acalabrutinib-venetoclax with or without obinutuzumab (Acala-Ven±Obi). Looking to the future, we consider the potential for CLL treatment regimens to be individualized based on minimal residual disease (MRD) status—an as-yet unapproved strategy in the management of CLL.

In our discussions, we focus on pivotal studies and/or those that provide influential clinical data shaping treatment selection strategies. We also include selected studies of investigational regimens with the potential to inform future standards of care.

First-line treatment selection

Treatment selection for previously untreated patients with CLL has historically been based on evaluation of a patient’s molecular disease characteristics (IGHV and TP53/del[17p]) and fitness [14,15,16,17]. Several clinical trials have demonstrated superior outcomes with targeted therapies versus CIT in patients with unmutated IGHV (uIGHV) and/or mutated TP53/del(17p) [6,7,8, 11, 18].

Historically, treatment algorithms have often incorporated the German CLL Study Group concept of patients being “go-go,” “slow-go,” or “no-go” based on how well patients are expected to tolerate purine analogs and/or anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies [19]. This approach is no longer relevant in healthcare systems where targeted therapies are widely available. CIT regimens are no longer recommended or have a very minor role in current guidelines for CLL from the US (National Comprehensive Cancer Network), Germany (Onkopedia), and France (French Innovative Leukemia Organization), making the “go-go” and “slow-go” concepts less relevant [1,2,3]. Recent algorithms retain the molecular-guided basis for treatment selection, but all BTK and BCL2 inhibitor–based regimens are viable options for most patients [1,2,3, 20].

With targeted therapies preferred, physicians cannot rely on generalized treatment algorithms. Instead, selecting the optimal treatment for a patient requires evaluation and weighting of many factors (Fig. 1). The key decision point is now continuous therapy with a BTK inhibitor versus fixed-duration therapy with a BCL2 inhibitor in combination with obinutuzumab or ibrutinib/acalabrutinib. For most patients, the process starts with a discussion of their treatment preferences.

First-line BTK inhibitor therapy

Several clinical trials have established that first-line monotherapy with ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or zanubrutinib provides durable responses with manageable safety profiles in patients with low- and high-risk disease (Table 1). Ibrutinib and acalabrutinib are also approved for use in combination with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies rituximab or obinutuzumab, although the benefit of this combination therapy versus monotherapy has not been proven [21]. In ELEVATE-TN (NCT02475681), acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab (Acala-Obi) led to prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) versus acalabrutinib monotherapy, but the study was not sufficiently powered for this comparison and, critically, there was no benefit from obinutuzumab addition for patients with del(17)(p13.1) and/or mutated TP53 [6].

Very long-term data are available for ibrutinib, the first approved BTK inhibitor for CLL. Durable responses were demonstrated in patients followed on continuous ibrutinib for up to 10 years in RESONATE-2 (NCT01722487; ibrutinib versus chlorambucil), 8 years in the single-arm PCYC-1102 trial (NCT01105247 and NCT01109069), and a median of 4.5 years in the Alliance A041202 trial (NCT01886872; ibrutinib with or without rituximab versus bendamustine-rituximab [BR]) [8,22,23,24,25].

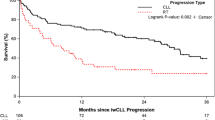

BTK inhibitors versus BCL2 inhibitors in high-risk patients

Continuous BTK inhibitor–based therapies are typically recommended for patients with high-risk disease. In the first-line setting, outcomes with BTK inhibitor therapy for patients with del(17p) and/or mutated TP53 are comparable to outcomes for patients without these features [6, 26, 27]. By contrast, for patients receiving Ven-Obi, those with del(17p) and/or mutated TP53 have shorter PFS compared with lower genetic risk patients [18].

The benefit of ibrutinib versus CIT regimens for high-risk disease has been demonstrated in several trials. In the Alliance A041202 trial of ibrutinib versus ibrutinib-rituximab (IR) versus BR, the 48-month PFS with ibrutinib and IR was 76% versus 47% with BR [22, 28]. The benefit of ibrutinib regimens (with no additional benefit of rituximab) versus BR was consistent for patients with or without TP53 abnormalities (mutated TP53/del[17p]), del(11q), complex karyotype, and uIGHV [22]. Among patients treated with ibrutinib regimens, the presence of TP53 abnormalities was not associated with a worse PFS outcome than in the absence of these abnormalities (HR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.51–1.91; P = 0.98) [22].

In the iLLUMINATE trial (NCT02264574) of ibrutinib-obinutuzumab (Ibr-Obi) versus chlorambucil-obinutuzumab (Clb-Obi), 42-month PFS was 74% for patients treated with Ibr-Obi, and outcomes were independent of del(17p)/TP53 mutation status (HR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.32–2.69; P = 0.895) [5]. A pooled analysis of RESONATE-2 and iLLUMINATE demonstrated similar outcomes with ibrutinib regimens in patients with or without high-risk genomic features, including del(17p) and mutated TP53 but also del(11q), uIGHV, and single-gene mutations in BIRC3, NOTCH1, SF3B1, and XPO1 [27].

Results from an investigator-initiated trial of ibrutinib monotherapy–treated patients (N = 34) with TP53 abnormalities underscore the durability of responses that can be achieved in this high-risk population. At 6 years, the estimated PFS and overall survival (OS) were 61% and 79%, respectively [29]. Although only one of 34 patients achieved undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD) (<10−4), the survival data indicate that deep responses are not a prerequisite for durable remission with ibrutinib [29].

Second-generation BTK inhibitors

The second-generation BTK inhibitors acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib have also demonstrated durable responses in patients with low- and high-risk disease features [6, 26]. In ELEVATE-TN (NCT02475681), 72-month PFS rates with Acala-Obi and acalabrutinib monotherapy for the overall population were 78.0% and 61.5%, respectively, compared with 17.2% for Clb-Obi. PFS at 72 months was not significantly different for patients with mutated IGHV (mIGHV) versus uIGHV treated with acalabrutinib monotherapy or Acala-Obi. PFS outcomes with acalabrutinib monotherapy were similar regardless of del(17)(p13.1) and/or TP53 mutation status. In contrast, patients with these features had numerically worse outcomes with Acala-Obi, appearing to derive no additional benefit from combination therapy versus acalabrutinib monotherapy [30].

In SEQUOIA (NCT03336333), at a median study follow-up time of 61.2 months in patients without del(17)(p13.1), there was an overall PFS benefit with zanubrutinib versus BR (HR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.21–0.40). Similar PFS outcomes were reported with zanubrutinib in patients with uIGHV versus mIGHV (HR: 1.35; 95% CI: 0.76–2.40) [26, 31], in contrast to the CLL14 trial with Ven-Obi, where uIGHV was identified as an adverse prognostic factor [32].

Patients with del(17)(p13.1) were not randomized in SEQUOIA because of poor outcomes with CIT in previous trials—these patients (n = 111) were instead treated with open-label zanubrutinib and analyzed separately [26]. Notably, the 60-month PFS in this high-risk population (72.2%) was comparable to outcomes of patients without del(17)(p13.1) randomized to receive zanubrutinib (75.8%) [26].

Ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or zanubrutinib?

Based on safety outcomes from head-to-head trials in the relapsed setting [1, 2, 33, 34], current treatment guidelines for CLL favor second-generation BTK inhibitors over ibrutinib across all lines of therapy [1,2,3, 35, 36]. Direct comparisons with acalabrutinib (ELEVATE-RR; NCT02477696) and zanubrutinib (ALPINE; NCT03734016) have demonstrated that their greater selectivity versus ibrutinib translates into overall improved safety profiles in CLL [33, 34]. In relapsed/refractory CLL, discontinuation rates due to adverse events (AEs) were lower with acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in ELEVATE-RR (14.7% versus 21.3% at a median follow-up of 40.9 months) and with zanubrutinib versus ibrutinib in ALPINE (21.4% versus 28.3% at a median follow-up of 42.5 months) [33, 34, 37].

Real-world rates of side effects and discontinuations are likely to be higher than in controlled trials and can contribute to a significant proportion of patients needing to change therapy. For example, in a retrospective, real-world analysis of 616 patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib, 21% of patients discontinued ibrutinib because of toxicity at a median follow-up of 17 months [38]. Switching to a second-generation BTK inhibitor is a viable option for patients with CLL who develop intolerance to ibrutinib [39, 40]. In a study of zanubrutinib monotherapy (NCT04116437), 54% of ibrutinib-intolerant patients with CLL (n = 28/52) and 70% of acalabrutinib ± ibrutinib–intolerant patients with CLL (n = 19/27) experienced no recurrence of intolerance-related AEs after switching to zanubrutinib. Additionally, 94% of efficacy-evaluable patients (n = 63/67) achieved disease control with zanubrutinib [39].

An important difference between the second-generation BTK inhibitors and ibrutinib is a reduced risk of cardiac AEs. All-grade atrial fibrillation/ atrial flutter was reduced with acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib (9.4% versus 16.0%; P = 0.02) and zanubrutinib versus ibrutinib (7.1% versus 17.0%) in ELEVATE-RR and ALPINE, respectively [33, 34, 37]. As with overall side effects, the rate of atrial fibrillation with ibrutinib is likely to be higher outside of clinical trials. In one study, which used systematic cardiac monitoring before and after initiation of therapy, 26% of patients with B-cell malignancies (n = 14/53) developed ibrutinib-associated atrial fibrillation after a median of 13 months [41].

In the absence of head-to-head data, it is difficult to differentiate the clinical properties of acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, although there are indications of differences between these agents from outcomes across trials. In relapsed/refractory CLL, the ALPINE trial demonstrated a statistically significant PFS advantage for zanubrutinib over ibrutinib, with clear and sustained separation of the PFS curves. In contrast, the ELEVATE-RR trial showed acalabrutinib to be non-inferior to ibrutinib, with overlapping PFS curves and no evidence of separation over time [33, 34, 37]. However, further research is needed to determine whether efficacy outcomes in the relapsed setting will be consistent with outcomes in the first-line setting.

Outcomes for patients with versus without TP53 aberrations in the relapsed setting with zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib were consistent with findings with these agents in the first-line setting from SEQUOIA and ELEVATE-TN. In this high-risk subgroup, PFS and response rates with zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib were comparable to the overall study populations in ALPINE and ELEVATE-RR, respectively [6, 26, 33, 34, 37].

In terms of comparative safety of the next-generation BTK inhibitors, the absence of head-to-head trials means that only indirect comparative data are available. A systematic review of 61 trials across different B-cell malignancies and lines of therapy found similar overall rates of treatment-emergent AEs between the two agents, with variations of the relative incidence of specific AEs. Neutropenia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypertension, hematuria, and cellulitis occurred more frequently with zanubrutinib, whereas atrial fibrillation, infections, pyrexia, cough, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, myalgias, headaches, and dizziness were more frequent with acalabrutinib [42]. A separate network meta-analysis in treatment-naive CLL patients of advanced age and/or with comorbidities supported the favorable tolerability of second-generation BTK inhibitors. Acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib had the most favorable safety profiles (Grade ≥3 and special AEs) of first-line targeted therapies in CLL, with zanubrutinib monotherapy associated with the lowest risk of AE-related treatment discontinuation [43]. While such data may be considered in individual cases where no other factors are decisive, cross-trial comparisons should be interpreted with caution.

First-line Ven-Obi

First-line fixed-duration Ven-Obi provides durable remissions with a manageable safety profile in fit and unfit patients with previously untreated CLL (Table 2) [44, 45]. The CLL14 trial (NCT02242942) established the superiority of Ven-Obi versus Clb-Obi in patients older than 70 years of age and/or with clinically relevant coexisting medical conditions [44]. At 5 years after randomization in CLL14, the estimated PFS rate was 62.6% versus 27.0% in favor of Ven-Obi [44]. uMRD (<10–4) in the peripheral blood 2 months after treatment was more common with Ven-Obi versus Clb-Obi (74.5% versus 32.9%), as were MRD remissions below 10−5 and 10−6 (66.2%/19.0% versus 39.8%/6.5%). In both arms, uMRD status at the end of therapy was associated with longer PFS and OS [11].

Genetic markers and patient outcomes

A multivariable analysis of the CLL14 study at 6 years identified del(17p), uIGHV, and lymph node size ≥5 cm as independent prognostic factors for PFS in patients treated with Ven-Obi [32]. Patients with TP53 abnormalities had a shorter median PFS (51.9 months versus 76.6 months) and 6-year OS rate (60.0% versus 81.9%) than those without TP53 abnormalities [32]. Although uIGHV was associated with poorer outcomes versus mIGHV, survival outcomes were still good with Ven-Obi in the uIGHV subgroup (median PFS: 64.8 months; 6-year OS: 77.7%), and with the benefit of long treatment-free intervals (median time to next treatment: 85.4 months) [32]. Similarly, although del(17p) and TP53 mutations are negative prognostic markers with Ven-Obi, this high-risk group achieved a median PFS of 51.9 months in CLL14 [32]. Therefore, while treatment with continuous BTK inhibitors may be generally favored for these high-risk patients, Ven-Obi may be a viable option depending on other disease and patient factors.

The GAIA (CLL13) trial (NCT02950051) was a head-to-head study of venetoclax-based, time-limited combination treatments versus CIT (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab [FCR] or BR) in 926 fit patients that established the superiority of Ven-Obi versus venetoclax-rituximab [45]. At Month 15, significantly higher rates of uMRD (<10−4) were achieved in the peripheral blood with Ven-Obi (86.5%; 97.5% CI: 80.6%–91.1%) and Ven-Obi-ibrutinib (92.2%; 97.5% CI: 87.3%–95.7%) versus CIT (52.0%; 97.5% CI: 44.4%–59.5%; both P < 0.001) but not with venetoclax-rituximab versus CIT (57.0%; 97.5% CI: 49.5%–64.2%; P = 0.32 versus CIT) [45].

In the final analysis, 5-year PFS rates were superior with Ven-Obi-ibrutinib (81.3%; HR: 0.34; 97.5% CI: 0.24–0.50; P < 0.001) versus CIT (50.7%) and numerically higher with Ven-Obi (69.8%) and venetoclax-rituximab (57.4%). The study was not powered to make further comparisons between groups, but subgroup comparisons indicate that IGHV status did not affect PFS outcomes in the Ven-Obi-ibrutinib group, whereas uIGHV was associated with poorer prognosis in the other treatment arms [46].

Tolerability of Ven-Obi

Ven-Obi was generally well tolerated across CLL14 and GAIA (CLL13). Discontinuation rates reflected differences in age and fitness of the study populations, with rates in CLL14 (16.0%, n = 34/212) almost three times higher than those in GAIA (CLL13) (5.7%, n = 13/228) [44, 45]. Common AEs also occurred more frequently in CLL14 than in GAIA (CLL13), including Grade 3–4 neutropenia (52.8% versus 45.2%), infections (17.5% versus 10.5%), and diarrhea (8.4% versus 1.8%) [44, 45]. These common AEs with Ven-Obi are manageable for most patients with supportive measures. For example, Grade 3 neutropenia accompanied by infection or fever, or Grade 4 neutropenia, may initially be managed with dose interruptions and/or reductions. In cases of recurrence, the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), either reactively or prophylactically, may be considered in accordance with institutional guidelines [47].

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), a potentially fatal side effect, requires special attention with venetoclax regimens (Table 3). In the GAIA (CLL13) trial in patients with a low burden of coexisting conditions, all-grade TLS (defined by the Cairo–Bishop criteria) occurred in 11% of patients treated with Ven-Obi, with no fatalities [45]. In the CLL14 trial, TLS (defined by the more stringent Howard criteria) occurred in 0.5% of patients treated with Ven-Obi, with all cases occurring after obinutuzumab and before venetoclax initiation. In a patient population with coexisting conditions and in which most patients had some form of renal impairment, there were no clinical or life-threatening TLS events [48,49,50,51]. These outcomes highlight that the risk of TLS with Ven-Obi can be managed effectively for patients for whom TLS monitoring is logistically feasible, and this regimen should not be discounted for patients with disease features associated with an increased risk of TLS.

First-line venetoclax–BTK inhibitor combination therapies

Ibr-Ven

Ibr-Ven was the first all-oral, fixed-duration regimen for CLL, and there are several ongoing trials with this regimen [12,13,49,50,51,52,53]. The GLOW study (NCT03462719) in older patients and/or those with comorbidities demonstrated significantly enhanced PFS with Ibr-Ven (n = 106) versus Clb-Obi (n = 105) (HR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.18–0.39; P < 0.0001) at a median follow-up of 64 months, with a benefit reported across prespecified subgroups [50, 54].

The phase II CAPTIVATE study (NCT02910583) is investigating Ibr-Ven in patients aged 70 years or younger assigned to two cohorts: fixed-duration treatment (n = 159) or MRD-guided treatment (n = 164), with a primary endpoint of complete response (CR) rates [12, 51]. At 4 years’ follow-up, the best CR rate in the fixed-duration cohort was 58% [51]. The overall 5.5-year PFS rate was 66% (95% CI: 58%‒72%), with PFS rates numerically lower in patients with uIGHV versus mIGHV (55% versus 63%) and with versus without TP53 aberrations (70% versus 36%) [55]. Unmutated IGHV was also associated with higher rates of CR (62% versus 47%) and uMRD (peripheral blood: 84% versus 67%; bone marrow: 64% versus 53%) [51]. OS at 5.5 years was 97%, and a subgroup analysis at 4 years demonstrated consistently high OS across all patient subgroups [55].

In the group receiving MRD-guided therapy–a strategy that is not currently approved in any context for the treatment of CLL— patients who achieved uMRD (<10−4) after three cycles of ibrutinib pre-treatment and 12 cycles of Ibr-Ven were randomly assigned to placebo or continuous ibrutinib until confirmed MRD relapse [12]. At a median follow-up of 31.3 months, best uMRD response rates were 75% (n = 123/164) in peripheral blood and 68% (n = 112/164) in bone marrow after 12 cycles of Ibr-Ven [12]. The addition of maintenance ibrutinib did not increase 1-year disease-free survival compared with placebo in patients who had achieved uMRD [12].

As in the fixed-duration cohort, rates of uMRD were higher for patients with uIGHV versus mIGHV (77% versus 56%) [12]. Rates of uMRD with or without del(17p) were similar (69% versus 68%) but numerically lower for patients with del(17p) or mutated TP53 compared with patients without either high-risk feature (66% versus 72%) [12].

FLAIR (ISRCTN01844152) is a large, UK-based, adaptive, multi-arm trial that in its most recent phase compares MRD-guided Ibr-Ven or ibrutinib monotherapy (each administered for up to 6 years) with FCR in previously untreated CLL—excluding patients with Richter’s transformation, symptomatic cardiac disease, or those with del(17p) in more than 20% of their CLL cells [49, 56].

With a median follow-up of 62.2 months, Ibr-Ven has demonstrated improved outcomes across multiple efficacy endpoints compared with ibrutinib monotherapy and FCR. Estimated 5-year PFS rates were 93.9% with Ibr-Ven, 79.0% with ibrutinib, and 58.1% with FCR. PFS was markedly superior with Ibr-Ven compared with both arms in patients with uIGHV, and numerically highest across all other genetic subgroups (mIGHV, ATM deletion, trisomy 12, del[13q], normal karyotype). OS rates showed the same trend, with Ibr-Ven superior compared with ibrutinib and FCR overall (95.9% versus 90.5% versus 86.5%, respectively) and numerically higher than ibrutinib and FCR in patients with uIGHV and mIGHV [56].

Ibr-Ven treatment also resulted in higher rates of uMRD (<10−4) within 2 years compared with FCR in bone marrow (66.2% vs. 48.3%) and peripheral blood (73.1% vs. 60.8%). No patients receiving ibrutinib monotherapy achieved uMRD [56]. The proportion of patients treated with Ibr-Ven meeting the MRD stopping rules increased from Years 2 to 4, with 48.3% stopped at 2 years, 56.3% at 3 years, and 68.1% at 4 years. These findings suggest that responses to Ibr-Ven may deepen over time but also indicate that MRD-guided treatment with Ibr-Ven can lead to prolonged therapy durations for many patients [56]. However, it is important to note that the FLAIR study was designed to compare ibrutinib monotherapy with Ibr-Ven, rather than to formally evaluate the clinical utility of MRD-guided treatment decisions.

This MRD-guided approach is currently unlicensed and further investigation is needed to determine how it can best guide decisions around Ibr-Ven treatment duration and discontinuation, and whether a uniform approach is appropriate for patients with differing disease characteristics. Despite these considerations, MRD-guided combinations of venetoclax with ibrutinib, zanubrutinib, or acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab are included as suggested first-line therapies for some patients in the most recent NCCN guidelines [2]. While there may be potential benefit in offering these regimens off-label in specific clinical scenarios, the best available evidence currently supports the use of fixed-duration BTK inhibitor–venetoclax combinations in accordance with their approved labels.

Tolerability of Ibr-Ven

Common AEs across the GLOW, CAPTIVATE, and FLAIR trials included diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, neutropenia, and arthralgia, all usually low-grade [12, 13, 49, 51]. In common with other ibrutinib-containing regimens, rates of atrial fibrillation were notable. At a median treatment duration of ~14 months, all-grade atrial fibrillation occurred in 7% (n = 12/164) and 4% (n = 7/159) of patients in the CAPTIVATE MRD and fixed-duration cohorts, respectively [12, 51]. Rates in the FLAIR study within 1 year of randomization were similar, with all-grade atrial fibrillation in 4% (n = 10/252) and Grade 3 in 0.8% (n = 2/252) of patients [49]. The GLOW trial, which included older and/or more comorbid patients compared with CAPTIVATE and FLAIR, reported atrial fibrillation in 14% of patients (n = 15/106) at a median treatment duration of 13.8 months and led to discontinuation of ibrutinib in two patients (2%) [13].

Additional cardiovascular events of concern were reported across these trials, with four on-treatment cardiac or sudden deaths (4%, n = 4/106) in the Ibr-Ven arm of the GLOW trial [13]. These patients had a CIRS score of 10 or greater or an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of 2, and a history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and/or diabetes [13]. In the younger and fitter population enrolled in CAPTIVATE (≤70 years and ECOG PS 0–2), there was one sudden death in the MRD cohort (0.6%, n = 1/164) and one in the fixed-duration cohort (0.6%, n = 1/159), which occurred during the ibrutinib pre-treatment phase [12, 51]. In the FLAIR study, which enrolled patients considered fit enough to receive FCR, there were three sudden unexplained or cardiac deaths (1.2%, n = 3/252) in patients treated with Ibr-Ven [49].

As with other ibrutinib regimens, it is essential to evaluate a patient’s risk of developing cardiovascular AEs before initiation of Ibr-Ven. Based on the safety outcomes across the trials considered here, clinicians may prefer therapies with a more favorable cardiovascular safety profile over Ibr-Ven for patients who meet the GLOW enrollment criteria, with Ibr-Ven reserved for younger and fitter patients [13].

Acala-Ven±Obi

Fixed-duration Acala-Ven and Acala-Ven-Obi are the most recent additions to the first-line treatment landscape for CLL. EMA approval was based on results of the AMPLIFY study (NCT03836261) comparing outcomes with fixed-duration Acala-Ven±Obi versus CIT (BR or FCR) in a fit and relatively young cohort (median age 61 years) of previously untreated patients with CLL without TP53 abnormalities [57, 58].

A prespecified interim analysis (median follow-up 40.8 months; N = 867) reported significantly improved PFS with either Acala-Ven (primary analysis; P = 0.004) or Acala-Ven-Obi (P < 0.001) compared with CIT (36-month PFS: 76.5%, 83.1%, and 66.5%, respectively) [57].

Undetectable MRD in the peripheral blood at the end of treatment (EOT)—an outcome associated with longer PFS—was achieved in 34.4% of the intention-to-treat population receiving Acala-Ven and 67.1% with Acala-Ven-Obi. Twelve weeks after EOT, these rates declined slightly to 29.9% and 65.0%, respectively [57]. These findings raise questions about the durability of response achievable with the AMPLIFY regimens, particularly with Acala-Ven. While acknowledging the limitations of cross-trial comparisons, uMRD rates of 34.4% in the intention-to-treat population (45.0% in evaluable patients) treated with Acala-Ven are markedly lower than the best peripheral blood uMRD rate of 77% reported in the CAPTIVATE study [51, 57]. In the GLOW study, 84.5% of patients treated with Ibru-Ven sustained uMRD in peripheral blood from 3 to 12 months after EOT—again, substantially higher than what was achieved with Acala-Ven in the AMPLIFY study [13, 57].

Analysis of safety outcomes showed relatively low incidences of Grade ≥3 cardiac AEs or hypertension that were comparable across the treatment groups, whereas rates of Grade ≥3 neutropenia or hemorrhage were higher with Acala-Ven-Obi versus Acala-Ven [57]. Rates of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were notably higher with Acala-Ven-Obi (20.1%) compared with Acala-Ven (7.9%) or CIT (10.8%). Similarly, serious AEs leading to death were more frequent with Acala-Ven-Obi (6.0%) versus Acala-Ven (3.4%) or CIT (3.5%) [57]. Based on these early findings, Acala-Ven-Obi may be best suited to younger, fitter patients who are able to tolerate an increased toxicity, with a modest efficacy benefit offered by this regimen compared with Acala-Ven [57].

Longer follow-up of AMPLIFY will determine the durability and tolerability of Acala-Ven and Acala-Ven-Obi combination regimens in this patient population [57]. Further studies are also needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these regimens in older patients and those with high-risk disease features.

A phase II study (NCT03580928) is investigating first-line Acala-Ven-Obi in previously untreated CLL, including patients with TP53 aberrations. Treatment may be discontinued after 15 or 24 cycles for patients with complete remission (as defined by iwCLL criteria) and uMRD4 in the bone marrow. After a median follow-up of 55.2 months, the median duration of treatment was 25 cycles (~25 months). Depth of response with MRD-guided Acala-Ven-Obi appeared independent of TP53 status, with no difference in the uMRD bone marrow rates at cycle 16, day 1 in patients with TP53 aberrations (42%; n = 19/45) compared with the overall population (42%; n = 30/72). Four-year PFS outcomes showed durable efficacy in patients with TP53 aberrations (70%), although this was numerically lower than for patients without TP53 aberrations (96%) [59].

Is there still a role for CIT?

Multiple trials have shown that CIT regimens produce inferior outcomes in patients with TP53 abnormalities and uIGHV, but young and fit patients without these genomic features can experience durable remissions [6,7,8, 11, 18]. Nevertheless, in health systems where targeted therapies are available, CIT regimens have a very limited role in current guidelines, including for patients with mIGHV [1, 2]. The authors of this review would not identify any clinical scenario where first-line CIT would be recommended when targeted therapies are available and accessible.

This unequivocal position is primarily driven by the long-term risks associated with CIT, such as secondary neoplasia, leukemias/myelodysplastic syndromes, and infections, as well as the similarly favorable outcomes with targeted therapy suggested in multiple trials despite shorter follow-up. In the Thompson et al. study of FCR, 6.3% of patients (n = 19/300) developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, which were fatal in 84% of patients (n = 16/19) [60].

Although the follow-up for targeted therapies discussed in this review, including BTK inhibitor and venetoclax-based combinations, is still relatively short compared with that for CIT, it is reassuring that there has been no signal of increased risk of myeloid malignancies with these regimens, beyond the elevated baseline risk associated with CLL itself [4]. However, it is worth noting that the AMPLIFY study reported a numerically higher incidence of any-grade second primary malignancies with Acala-Ven (5.2%; n = 15/222) and Acala-Ven-Obi (4.2%; n = 12/242) compared with FCR/BR (0.8%; n = 2/185). This emerging signal warrants longer follow-up and continued vigilance [57].

Future outlook

As illustrated earlier, treatment selection for previously untreated patients with CLL requires integration of evidence from different clinical trials with individual patient characteristics and preferences. Several ongoing trials will help to shape these conversations in the future through additional data on several areas of current uncertainty. To address the question of continuous versus fixed-duration therapy, the CLL17 trial (NCT04608318) will examine first-line ibrutinib monotherapy as a continuous therapy until time of progression or unacceptable toxicity, or fixed-duration therapy with either Ven-Obi for 1 year or Ibr-Ven for 15 months. The primary endpoint of the trial is PFS, with several secondary endpoints focused on MRD outcomes [61].

To better understand the optimal combination partner for a first-line venetoclax-based doublet, the MAJIC trial (NCT05057494) is comparing first-line Acala-Ven versus Ven-Obi [62]. MRD assessment is a co-primary endpoint of MRD-driven finite Acala-Ven versus MRD-driven finite Ven-Obi, with patients able to receive 1 or 2 years of venetoclax-based therapy depending on whether they achieve uMRD at the end of the first year. The second co-primary endpoint is PFS [62].

Looking further ahead, the ongoing CELESTIAL-TNCLL study (NCT06073821) is comparing zanubrutinib plus the second-generation BCL2 inhibitor sonrotoclax with Ven-Obi in patients with previously untreated CLL with or without mutated TP53/del(17p) [63]. This phase III study will build on promising findings from a phase I study of zanubrutinib-sonrotoclax in patients with various B-cell malignancies (NCT04277637) [64, 65]. Preliminary data at a median follow-up of 19.4 months for 137 patients with previously untreated CLL suggested zanubrutinib-sonrotoclax was well tolerated. Neutropenia was the most common Grade ≥3 AE (23%–24% of patients), but these events were mostly transitory and were not associated with a higher rate of Grade ≥3 infection; no patients experienced TLS. Efficacy was extremely promising, with 48-week best blood uMRD4 rates of 79% (n = 27/34) with 160 mg and 90% (n = 43/48) with 320 mg, and only one PFS event, which was in the lower dose cohort [64, 65]. Zanubrutinib has also been assessed in combination with venetoclax as MRD-guided treatment in arm D of the SEQUOIA trial (n = 114) [66]. With a median follow-up of 31.2 months, best peripheral blood uMRD (<10−4) rates were similar for patients with and without TP53 aberrations (59% and 60%, respectively). Estimated 2-year PFS rates were also similar, at 94% (95% CI: 85%–98%) in patients with TP53 aberrations and 89% (95% CI: 76%–95%) in patients without. The safety profile was in line with expectations from previous studies [66].

Finally, two MRD-guided approaches using zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab are being evaluated in patients with previously untreated CLL [67,68,69]. In the BOVen study (NCT03824483), the triple therapy is administered until progressive disease, unacceptable toxicity, or uMRD (<10−4), with a minimum of 8 months and a maximum of 24 months of treatment based on MRD status. At a median follow-up of 57 months, 92% of patients (n = 46/50) achieved the primary endpoint of uMRD in both peripheral blood and bone marrow [67, 68]. Patients who reverted to MRD positivity were eligible for retreatment. At a median follow-up of 14 months, 92% of evaluable patients (n = 11/12) achieved an overall response and 46% (n = 6/13) regained uMRD status. The BOVen regimen was generally well tolerated, with no unexpected safety signals observed during long-term follow-up [67, 68]. In the BruVenG study (NCT05650723), from which interim results are expected in late 2025, patients are treated initially with zanubrutinib-venetoclax, and obinutuzumab is added only for patients who remain MRD-positive [69].

Summary

Targeted therapies have dramatically improved outcomes for patients with CLL, particularly for patients unsuitable for CIT because of poor fitness and comorbidities or because of higher genetic risk markers, such as TP53 abnormalities and/or uIGHV. In this review, we have assessed the key evidence supporting the use of first-line single-agent zanubrutinib/acalabrutinib, Ven-Obi, and venetoclax–BTK inhibitor combinations. With these regimens, it is more difficult to provide a generalized treatment algorithm than it was in the CIT era. For most patients, particularly those with mIGHV and no high-risk disease features or confounding comorbidities/comedications, there will be more than one viable treatment option in the first-line setting. Consequently, several factors require evaluation, and weight should be given to the patient’s preferences. With effective shared decision-making, there has never been a better opportunity for prescribers to provide patients with CLL with a therapy that meets their individual therapeutic goals.

References

Wendtner C-M, Al-Sawaf O, Binder M, Dreger P, Eichhorst B, Gregor M, et al. Onkopedia Guidelines: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und Medizinische Onkologie (DGHO), Österreichische Gesellschaft für Hämatologie undOnkologie (OeGHO), Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Hämatologie (SGH+SSH), and Schweizerische Gesellschaft für MedizinischeOnkologie (SGMO), 2024). https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/archive/guidelines/chronische-lymphatische-leukaemie-cll/version-30092025T131113/@@guideline/html/index.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2025.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma V.1.2026 (National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), 2025). NCCN.org. Accessed 28 Aug 2025.

Aurran T, Bussot L, de Guibert S, Dilhuydy M-S, Feugier P, Fornecker L-M, et al. Recommandations de prise en charge de la leucemie lymphoide chronique actualisation des algorithmes de traitement (French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO), 2023).

Barr PM, Owen C, Robak T, Tedeschi A, Bairey O, Burger JA, et al. Up to 8-year follow-up from RESONATE-2: first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022;6:3440–50.

Moreno C, Greil R, Demirkan F, Tedeschi A, Anz B, Larratt L, et al. First-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab: final analysis of the randomized, phase III iLLUMINATE trial. Haematologica. 2022;107:2108–20.

Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, Skarbnik A, Pagel JM, Flinn IW, et al. Efficacy and safety in a 4-year follow-up of the ELEVATE-TN study comparing acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2022;36:1171–5.

Tam CS, Brown JR, Kahl BS, Ghia P, Giannopoulos K, Jurczak W, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1031–43.

Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, Zhao W, Booth AM, Ding W, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2517–28.

Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Hanson CA, Paietta EM, O’Brien S, Barrientos J, et al. Long-term outcomes for ibrutinib-rituximab and chemoimmunotherapy in CLL: updated results of the E1912 trial. Blood. 2022;140:112–20.

Hillmen P, Pitchford A, Bloor A, Broom A, Young M, Kennedy B, et al. Ibrutinib and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab for patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (FLAIR): interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:535–52.

Al-Sawaf O, Zhang C, Jin HY, Robrecht S, Choi Y, Balasubramanian S, et al. Transcriptomic profiles and 5-year results from the randomized CLL14 study of venetoclax plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2147.

Wierda WG, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, Kipps TJ, Opat S, Tedeschi A, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: primary analysis results from the minimal residual disease cohort of the randomized phase II CAPTIVATE study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:3853–65.

Kater AP, Owen C, Moreno C, Follows G, Munir T, Levin M-D, et al. Fixed-duration ibrutinib-venetoclax in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and comorbidities. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2200006.

Furstenau M, Hallek M, Eichhorst B. Sequential and combination treatments with novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104:2144–54.

Eichhorst B, Robak T, Montserrat E, Ghia P, Niemann CU, Kater AP, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:23–33.

Hampel PJ, Parikh SA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment algorithm 2022. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:161.

Tausch E, Schneider C, Stilgenbauer S. Risk-stratification in frontline CLL therapy: standard of care. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2024;2024:457–66.

Tausch E, Schneider C, Robrecht S, Zhang C, Dolnik A, Bloehdorn J, et al. Prognostic and predictive impact of genetic markers in patients with CLL treated with obinutuzumab and venetoclax. Blood. 2020;135:2402–12.

Goede V, Hallek M. Optimal pharmacotherapeutic management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: considerations in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:163–76.

Soumerai JD, Barrientos J, Ahn I, Coombs C, Gladstone D, Hoffman M, et al. Consensus recommendations from the 2024 Lymphoma Research Foundation workshop on treatment selection and sequencing in CLL or SLL. Blood Adv. 2025;9:1213–29.

Shah HR, Stephens DM. Is there a role for anti-CD20 antibodies in CLL? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2021;2021:68–75.

Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, Zhao W, Booth AM, Ding W, et al. Long-term results of Alliance A041202 show continued advantage of ibrutinib-based regimens compared with bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2021;138:639.

Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Tedeschi A, Sarma A, et al. Final analysis of the RESONATE-2 study: up to 10 years of follow-up of first-line ibrutinib treatment for CLL/SLL. Blood. 2025;146:2168–76.

Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Flinn IW, Burger JA, Blum K, et al. Ibrutinib treatment for first-line and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final analysis of the pivotal phase Ib/II PCYC-1102 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3918–27.

O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre SE, Mato AR, Hillmen P, Tam C, et al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a phase 2, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1409–18.

Tam CSL, Ghia P, Shadman M, Munir T, Opat S, Walker P, et al. SEQUOIA 5-year follow-up in arm C: frontline zanubrutinib monotherapy in patients with del(17p) and treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL). J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:7011.

Burger JA, Robak T, Demirkan F, Bairey O, Moreno C, Simpson D, et al. Up to 6.5 years (median 4 years) of follow-up of first-line ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma and high-risk genomic features: integrated analysis of two phase 3 studies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022;63:1375–86.

Woyach JA, Perez Burbano G, Ruppert AS, Miller C, Heerema NA, Zhao W, et al. Follow-up from the A041202 study shows continued efficacy of ibrutinib regimens for older adults with CLL. Blood. 2024;143:1616–27.

Ahn IE, Tian X, Wiestner A. Ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with TP53 alterations. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:498–500.

Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, Skarbnik AP, Patel K, Flinn IW, et al. Acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab improves survival vs chemoimmunotherapy in treatment-naive CLL in the 6-year follow-up of ELEVATE-TN. Blood. 2025;146:1276–85.

Shadman M, Munir T, Robak T, Brown JR, Kahl BS, Ghia P, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in patients with treatment-na‹ve chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma: median 5-year follow-up of SEQUOIA. J Clin Oncol. 2024;43:780–7.

Al-Sawaf O, Robrecht S, Zhang C, Olivieri S, Chang YM, Fink AM, et al. Venetoclax-obinutuzumab for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 6-year results of the randomized phase 3 CLL14 study. Blood. 2024;144:1924–35.

Byrd JC, Hillmen P, Ghia P, Kater AP, Chanan-Khan A, Furman RR, et al. Acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of the first randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:3441–52.

Brown JR, Eichhorst B, Hillmen P, Jurczak W, Kaźmierczak M, Lamanna N, et al. Zanubrutinib or ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:319–32.

Owen C, Banerji V, Johnson N, Gerrie A, Aw A, Chen C, et al. Canadian evidence-based guideline for frontline treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2022 update. Leuk Res. 2023;125:107016.

Owen C, Eisinga S, Banerji V, Johnson N, Gerrie AS, Aw A, et al. Canadian evidence-based guideline for treatment of relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2023;133:107372.

Brown JR, Eichhorst B, Lamanna N, O’Brien SM, Tam CS, Qiu L, et al. Sustained benefit of zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib in patients with R/R CLL/SLL: final comparative analysis of ALPINE. Blood. 2024;144:2706–17.

Mato AR, Nabhan C, Thompson MC, Lamanna N, Brander DM, Hill B, et al. Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica. 2018;103:874–9.

Shadman M, Burke JM, Cultrera J, Yimer HA, Zafar SF, Misleh J, et al. Zanubrutinib is well tolerated and effective in patients with CLL/SLL intolerant of ibrutinib/acalabrutinib: updated results. Blood Adv. 2025;9:4100–10.

Rogers KA, Thompson PA, Allan JN, Coleman M, Sharman JP, Cheson BD, et al. Phase II study of acalabrutinib in ibrutinib-intolerant patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2021;106:2364–73.

Baptiste F, Cautela J, Ancedy Y, Resseguier N, Aurran T, Farnault L, et al. High incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients treated with ibrutinib. Open Heart. 2019;6:e001049.

Hwang S, Wang J, Tian Z, Qi X, Jiang Y, Zhang S, et al. P632: Comparison of treatment-emergent adverse events of acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib in clinical trials in B-cell malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HemaSphere. 2023;7:e47546cf.

Stożek-Tutro A, Reczek M, Kawalec P. Safety profile of first-line targeted therapies in elderly and/or comorbid chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients (unfit subpopulation). A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;201:104428.

Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, Fink A-M, Tandon M, Dixon M, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2225–36.

Eichhorst B, Niemann CU, Kater AP, Fürstenau M, von Tresckow J, Zhang C, et al. First-line venetoclax combinations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1739–54.

Fürstenau M, Robrecht S, von Tresckow J, Zhang C, Gregor M, Thornton P, et al. The triple combination of venetoclax-ibrutinib-obinutuzumab prolongs progression-free survival compared to venetoclax-CD20-antibody combinations and chemoimmunotherapy in treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final analysis from the phase 3 GAIA/CLL13 trial. EHA 2025, Milan, Italy.

Waggoner M, Katsetos J, Thomas E, Galinsky I, Fox H. Practical management of the venetoclax-treated patient in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2022;13:400–15.

Al-Sawaf O, Fink A-M, Robrecht S, Sinha A, Tandon M, Eichhorst BF, et al. Prevention and management of tumor lysis syndrome in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions treated with venetoclax-obinutuzumab or chlorambucil-obinutuzumab: results from the randomized CLL14 trial. Blood. 2019;134:4315.

Munir T, Cairns DA, Bloor A, Allsup D, Cwynarski K, Pettitt A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapy guided by measurable residual disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:326–37.

Moreno C, Munir T, Owen C, Follows G, Hernandez Rivas J-A, Benjamini O, et al. First-line fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax (Ibr+Ven) versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab (Clb+O): 55-month follow-up from the GLOW study. Blood. 2023;142:634.

Tam CS, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, Kipps TJ, Jacobs R, Opat S, et al. Fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL: primary analysis of the CAPTIVATE FD cohort. Blood. 2022;139:3278–89.

Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, Ferrajoli A, Burger JA, Borthakur G, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a nonrandomized phase 2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1213–9.

Hillmen P, Pitchford A, Bloor A, Pettitt A, Patten P, Forconi F, et al. S145: The combination of ibrutinib plus venetoclax results in a high rate of MRD negativity in previously untreated CLL: the results of the planned interim analysis of the phase III NCRI FLAIR trial. HemaSphere. 2022;6:46–7.

Niemann CU, Munir T, Owen C, Follows G, Hernandez Rivas J-A, Benjamini O, et al. First-line ibrutinib plus venetoclax vs chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in elderly or comorbid patients (pts) with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): GLOW study 64-month follow-up (FU) and adverse event (AE)-free progression-free survival (PFS) analysis. Blood. 2024;144:1871.

Ghia P, Barr PM, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, Tedeschi A, Kipps TJ, et al. Final analysis of fixed-duration ibrutinib + venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) in the phase 2 CAPTIVATE study. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:7036.

Munir T, Girvan S, Cairns DA, Bloor A, Allsup D, Varghese AM, et al. Measurable residual disease-guided therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2025;393:1177–90.

Brown JR, Seymour JF, Jurczak W, Aw A, Wach M, Illes A, et al. Fixed-duration acalabrutinib combinations in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:748–62.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in combination with venetoclax (ABT-199), with and without obinutuzumab (GA101) versus chemoimmunotherapy for previously untreated CLL (AMPLIFY). 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03836261. Accessed 18 Jun 2024.

Davids MS, Ryan CE, Lampson BL, Ren Y, Tyekucheva S, Fernandes SM, et al. Phase II study of acalabrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab in a treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia population enriched for high-risk disease. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:788–99.

Thompson PA, Bazinet A, Wierda WG, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, Saha S, et al. Sustained remissions in CLL after frontline FCR treatment with very-long-term follow-up. Blood. 2023;142:1784–8.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Ibrutinib monotherapy versus fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab versus fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) (CLL17). 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04608318. Accessed 18 Jun 2024.

Ryan CE, Davids MS, Hermann R, Shahkarami M, Biondo J, Abhyankar S, et al. MAJIC: a phase III trial of acalabrutinib + venetoclax versus venetoclax + obinutuzumab in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2022;18:3689–99.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of sonrotoclax (BGB-11417) plus zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) compared with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab in participants with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06073821. Accessed 9 Jul 2024.

Tam CS, Anderson MA, Lasica M, Verner E, Opat SS, Ma S. et al. Combination treatment with sonrotoclax (BGB-11417), a second-generation BCL2 inhibitor, and zanubrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, is well tolerated and achieves deep responses in patients with treatment-na‹ve chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (TN-CLL/SLL): data from an ongoing phase 1/2 study. Blood. 2023;142:327

Soumerai JD, Cheah CY, Anderson MA, Lasica M, Verner E, Opat SS. Sonrotoclax and zanubrutinib as frontline treatment for CLL demonstrates high MRD clearance rates with good tolerability: data from an ongoing phase 1/1b study BGB-11417-101. Blood. 2024;144:1012

Shadman M, Munir T, Ma S, Lasica M, Tani M, Robak T, et al. Zanubrutinib and venetoclax for patients with treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with and without del(17p)/TP53 mutation: SEQUOIA arm D results. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:2409–17.

Soumerai JD, Mato AR, Dogan A, Seshan VE, Joffe E, Flaherty K, et al. Zanubrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax with minimal residual disease-driven discontinuation in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e879–90.

Soumerai JD, Dogan A, Seshan V, Flaherty KL, Slupe N, Carter J, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of zanubrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax (BOVen) in treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 5-year follow up, retreatment outcomes, and impact of MRD kinetics (ΔMRD400). Blood. 2024;144:1867.

Allan JN, Helbig D, Mulvey E, Nazir S, Stewart S, Lapinta ML, et al. Zanubrutinib and venetoclax as initial therapy for CLL/SLL with obinutuzumab triplet consolidation in patients with minimal residual disease positivity (BruVenG). Blood. 2023;142:3285.

Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, Tedeschi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia. 2020;34:787–98.

Munir T, Girvan S, Cairns D, Bloor A, Allsup D, Varghese A, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax with MRD-guided duration of treatment is superior to both continuous ibrutinib monotherapy and FCR for previously untreated CLL: report of the phase III UK FLAIR study. EHA 2025, Milan, Italy.

Jain N, Keating MJ, Thompson PA, Ferrajoli A, Senapati J, Burger JA, et al. Combined ibrutinib and venetoclax for first-line treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): 5-year follow-up data. Blood. 2023;142:4635–9.

Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, Ferrajoli A, Burger J, Borthakur G, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2095–103.

Genentech USA, Inc. VENCLEXTA (venetoclax tablets), for oral use – US prescribing information. Genentech USA, Inc.; South San Francisco, CA, USA; 2022.

AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG. Venclyxto 10/50/100 mg film-coated tablets – summary of product characteristics. AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG; Ludwigshafen, Germany; 2024.

Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Hallek M. Preventing and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome and other toxicities of venetoclax during treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020;2020:357–62.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by Luke Smith, PhD, of Porterhouse Medical, to collate and incorporate author input on the manuscript, all carried out under the authors’ direction. Editorial support was funded by BeOne Medicines Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSD, SS, and CST contributed equally as co-first authors through the conception, drafting, critical review, and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MSD: Research funding from Ascentage Pharma, MEI Pharma, and Novartis; honoraria from AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Ascentage Pharma, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, BMS, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Genmab, Janssen, Merck, Nuvalent, Secura Bio, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and TG Therapeutics. SS: Honoraria from AbbVie, Acerta Pharma, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, and Sunesis Pharmaceuticals. CST: Research funding from AbbVie, BeOne Medicines Ltd, and Janssen; honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Janssen, and Merck.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Davids, M.S., Stilgenbauer, S. & Tam, C.S. First-line treatment for CLL in the era of targeted therapy. Blood Cancer J. 16, 19 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01434-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01434-2