Abstract

Introduction This study looks at the amount of oral medicine activity in oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) units in both South East Wales and South West England, and to consider the development of training programmes in oral medicine and OMFS, to determine how to best deliver a service which would benefit patients with oral medicine diagnoses.

Materials and methods Following institutional approvals, local OMFS units in South East Wales and South West England collected data from OMFS outpatient clinics to determine what proportion of patient diagnoses fell within the scope of practice of oral medicine.

Results In South East Wales in 2017, patients with oral medicine diagnoses formed 45% of total outpatient activity in OMFS outpatient clinics compared to 37% of patients in the South West of England in 2021. Patients with oral medicine diagnoses were predominantly female and in the older age groups.

Discussion and conclusions Changing age demographics suggest that the demand for specialist oral medicine services will continue to rise. Outside of the university dental hospital setting, where all UK oral medicine units are currently located, there is a growing need for specialists in oral medicine to work alongside colleagues in OMFS in district general hospitals to provide specialist oral medicine care to an increasingly large and complex patient group, ideally as part of a managed clinical network.

Key points

-

Specialist training in oral medicine and oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) has evolved such that there is limited training in oral medicine within OMFS programmes and reduced overlap of competencies between specialties.

-

Patients and their disease complexities are such that for some patients, their diagnosis and management is beyond the scope of training and experience of OMFS colleagues.

-

Changing age demographics suggest that the demand for specialist oral medicine services will continue to rise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A 2009 study examined the provision of care for patients with oral medicine diagnoses in departments of oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS)1 and estimated that 20-40% of total clinic time was used in managing these patients. OMFS units are located most commonly in district general hospitals serving a local region, while specialist oral medicine clinics are located in major cities within university dental hospitals, and typically serve a large geographic area, meaning patients travel long distances to access this specialist care. The majority of patients managed in these specialist oral medicine clinics are in the older age demographic and the reasons for attendance may include diagnosis and management of mucosal disease, salivary gland disorders, orofacial pain, oral manifestations of wider systemic disease, and for provision of specialist-initiated medications for rare or unusual conditions.

In both England and Wales' national healthcare organisations, there has been a push to develop managed clinical networks (MCNs) in oral medicine such that practitioners with different levels of training, qualification and experience can manage patients closer to their home address, ideally in a primary care setting. This would avoid the need for referral into regional secondary care specialist units,2,3 thus avoiding or reducing costs to the healthcare provider (as outpatient episode unit costs are higher in specialist settings than primary care) and to the patient (travelling time and cost of longer journeys). The 2009 survey of OMFS departments found that reasons for referring patients onward to specialist oral medicine services included: i) for specialist expertise; ii) due to failed treatments thus far; and importantly iii) a lack of time in outpatient clinics.1

In 2017, there were a series of service reviews in South East Wales in a number of district general hospitals with OMFS clinic provision in two local university health boards (UHBs). These reviews collected data for patients with oral medicine diagnoses who attended OMFS outpatient clinics, with a view to establishing the level of oral medicine demand and how an MCN could be developed to serve the needs of this patient group. The two health boards (there have since been some name and boundary changes) comprised Cwm Taf UHB - centred around Merthyr Tydfil and serving the centre and middle of South Wales - and Aneurin Bevan UHB - centred around Newport and serving the East Wales population. A third South East Wales health board (Cardiff and Vale UHB) was not included in the data collection, since it is where the specialist oral medicine unit is located, within the University Dental Hospital and School.

In addition to the South East Wales 2017 service reviews, another series of reviews were carried out in five regional OMFS units in district general hospitals within South West England during 2021, to further assist planning for possible future oral medicine MCNs. These units were those located in Bath, Taunton, Torbay, Truro and Plymouth. The regional health area of Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucester was not included, as this is where the specialist oral medicine unit is located, within Bristol University Dental Hospital and School.

Materials and methods

All service reviews were approved by the relevant local audit and clinical governance groups and once collected and duplicates removed, all patient data were anonymised for analysis. A standardised data collection template was used to collect outpatient attendance data over several weeks for each regional OMFS unit in 2017 and 2021. Anonymised data included sex, age, first part of postcode and diagnosis/reason for attendance. Oral medicine diagnoses were those where treatment would be non-surgical or where simple investigations and treatment may be performed under local anaesthetic (for example, incisional or excisional biopsy) to separate them from patients who would require inpatient or outpatient surgical procedures to manage their presenting complaints. The South East Wales 2017 and South West England 2021 data were analysed separately, and then combined for further analysis.

Results

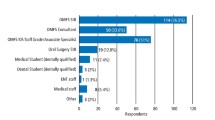

South East Wales and South West England service reviews collected anonymous data for nearly 7,000 patients attending OMFS outpatient clinics and identified those patients with diagnoses falling within standard oral medicine practice. The division of sex of patients attending both regions is very similar, with more women than men in both regions (Fig. 1). The majority of patients with oral medicine diagnoses were older, being in the 45-64 years and 65-85 years age ranges (Fig. 2).

Swellings and lumps was the most common category of oral medicine diagnosis for patients seen in OMFS clinics, followed by white patches and chronic orofacial pain (Fig. 3). Temporomandibular joint (TMJ)-related orofacial pain diagnoses were excluded from the oral medicine diagnoses data collection. Firstly, this group is more numerous and would have skewed the orofacial pain data, and secondly, most patients with TMJ-related diagnoses do not need specialist management from oral medicine clinicians and are managed by colleagues in OMFS.

Table 1 shows examples of specific oral medicine diagnoses that were recorded within the broader diagnostic categories during the study. During the data collection periods, 2,168 patients were seen in OMFS clinics in South East Wales, and 4,578 patients were seen in OMFS clinics in South West England: a total of 6,746 patients. In South East Wales, oral medicine diagnoses were 45% of the total, and in South West England, 37% of the total. Combining the data from the two regions produced a figure of 40% of outpatient OMFS patient diagnoses falling within the scope of oral medicine specialist practice (Table 2).

Discussion

These service reviews of oral medicine activity in regional OMFS units in South East Wales and the South West of England showed that, on average, 40% of outpatient activity in OMFS regional units is for patients with diagnoses that are within the scope of practice of oral medicine. The age profile for patients in South East Wales is slightly younger than for South West England but both regions show that the age profiles for patients attending OMFS outpatient clinics for diagnosis and treatment of oral medicine conditions are toward the older age group.

Speciality training in OMFS

The UK OMFS national specialist society, the British Association for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, describes the speciality as 'the surgical speciality concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of diseases affecting the mouth, jaws, face and neck'.4

Modern OMFS practice evolved out of hospital oral surgery and the earlier incarnations of hospital consultant dental surgeons, who had a fairly limited scope of practice. The evolution of OMFS was mirrored by changes in training and qualification. Initially held with the General Dental Council (GDC), OMFS became a surgical speciality regulated by the General Medical Council (GMC) in 1995, when a specialist list was introduced to mirror developments in Europe.5A Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) in OMFS is awarded and individuals can join the GMC specialist list. Prior to 1995, trainees were awarded a CCT in oral surgery and oral medicine, and when the GDC introduced specialists lists in 1998,6 many OMFS specialists used their oral surgery and oral medicine CCT to join the oral medicine specialist list. As of June 2022, there are 84 entries on the GDC specialist list for oral medicine, and only one clinician also appears on the GMC specialist list for OMFS. In the current GMC curriculum for speciality training in OMFS, 'oral medicine' is mentioned just twice.7

OMFS speciality training programmes in the USA cater for those both with and without a medical degree. Recent publications evaluated residents' (speciality trainees) and programme directors' views on confidence across a range of curriculum competencies, including areas of surgery, TMJ disorders and oral medicine. For both groups, there was a perceived training deficit in oral medicine.8,9

In both the UK and USA, it is possible to complete additional periods of training outside of the formal OMFS training programmes (out of programme experience [OOPE]) to gain additional skills and knowledge. None of these OOPE fellowships relate to oral medicine.10,11

Speciality training in oral medicine

The speciality and scope of practice of oral medicine is described by the GDC as 'care for oral health of patients with chronic recurrent and medically related disorders of the mouth and with their diagnosis and non-surgical management'.12 Until the introduction of the current 2010 GDC curriculum for oral medicine, entry to training required qualifications in both medicine and dentistry. In 2010, singly qualified applicants (dental degree alone) became eligible to enter training, having a five-year speciality training programme, whereas for those with both medical and dental qualifications, training time was reduced to three years. Oral medicine scope of practice continues to develop, and it is routine for oral medicine units to manage patients with inflammatory and immunobullous disease with systemic medications, including disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and immunosuppressants. Chronic orofacial pain is often managed with a range of anticonvulsant and antidepressant medications. Patients on such systemic medications often require regular blood test monitoring and shared care with the patient's medical practitioner. Patients presenting with oral manifestations of systemic disease typically need their oral medicine specialists to work closely with colleagues in rheumatology, dermatology, gastroenterology, neurology and allergy/immunology for multidisciplinary care. This specialist care is often outwith the training and experience of colleagues in OMFS.

The UK speciality training programmes of both OMFS and oral medicine have evolved in the last 10-20 years, such that there is increasingly less overlap in knowledge and experience between the two specialties.

Changing population demographics

Office for National Statistics surveys show that the population in the UK is ageing,13and we know from published research that older patients have greater medical comorbidity and more associated medications.14,15 Since oral medicine clinics cater for many older patients presenting with orofacial disease or oral manifestations of systemic disease, the demand for oral medicine services will only increase with changing population demographics.

Managed clinical networks

Following the publication of the England and Wales documents promoting the development of MCNs in oral medicine, there has been little progress with this in South East Wales or South West Engand.2,3 Currently, the location of specialist oral medicine services in both areas is in university dental hospitals, with long travel times for patients to reach these centres. In Wales, patients travelling from West Wales typically have travel times in excess of two hours to receive specialist oral medicine care in Cardiff. The same is true in South West England, where travel times from Plymouth (one of the centres in this study) to Bristol are in excess of two-and-a-half hours. In the UK, MCNs with oral medicine specialists co-located with OMFS, restorative and orthodontic colleagues in a district general hospital, and primary care clinics staffed by dentists with some additional training and experience in oral medicine in a hub-and-spoke arrangement, would allow for a more efficient and local service for patients and easier access to oral medicine specialists where needed. In South West England, there are already five dental speciality MCNs in place, demonstrating that these are possible.16

MCNs aim to deliver the care of patients closer to their home and by clinicians with appropriate levels of knowledge and skill (patient journey is illustrated in the Commissioning guide for oral medicine and oral surgery).2 Appendix 1 shows an example of the different levels of complexities which relate to provision of care by different clinicians. At present, all levels of care are delivered by specialists in OMFS and oral medicine, typically in the hospital environment. Level 1 conditions could be managed by general dental practitioners (GDPs), with some revision and updating of their undergraduate training. With additional training by specialists in oral medicine, and development of some simple surgical skills, dentists (GDPs) with enhanced skills (DES) could manage Level 2 conditions and undertake simple mucosal biopsy procedures and refer onwards as necessary. The evolution of DES is well-described by Rooney.17 Studies of DES in restorative specialties report positive experiences from those that take part, with investments in suitable training and support, but some expressed concerns with the financial rewards of delivering more complex patient care within the constraints of a primary care-based government-funded system.18,19,20,21It should also be recognised that implementation of an MCN in oral medicine also requires an appropriate specialist service at the centre, and reinforces the need to have specialists in oral medicine located outside of the relatively few dental hospitals in the UK, and co-located with OMFS colleagues in district general hospitals with an appropriate geographic spread. The planning of such a service in West Yorkshire was described in 2017 but has yet to be implemented some five years later, perhaps highlighting the ongoing difficulties of trying to establish oral medicine specialist service provision outside of a dental hospital setting.22

Conclusion

The specialties of oral medicine and OMFS are complementary in that one employs non-surgical management and the other surgical management to care for patients presenting with orofacial disease. However, having identified the divergence in training between oral medicine and OMFS, it would be unreasonable to require that OMFS surgeons in regional district general hospitals be capable of managing the more complex presentations, diagnoses and disease management requirements of oral medicine patients. The service reviews in South East Wales and the South West of England have shown that 37-45% of regional OMFS unit outpatient activity is related to care for patients with oral medicine diagnoses, and there is no reason to suspect that this figure would not be replicated across the UK. Given these findings, we argue that dental/head and neck regional hospital units should include a specialist in oral medicine alongside OMFS colleagues, as well as those in restorative dentistry and orthodontics, whose roles are long-established. Taking oral medicine patients out of OMFS outpatient clinics will allow surgical colleagues to more efficiently manage patients needing their particular expertise. The skill mix of specialist clinicians in district general hospitals needs to better match the case mix of patients being referred to these units, and once oral medicine specialists are established in regional centres, the MCNs can follow, to the benefit of both patients and their referring dentists.

References

Harrison W, O'Regan B. Provision of oral medicine in departments of oral and maxillofacial surgery in the UK: national postal questionnaire survey 2009. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 49: 396-399.

NHS England. Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine. 2015. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-oral.pdf (accessed June 2022).

Welsh Government. The future development of oral surgery and oral medicine services in Wales. 2015. Available at https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-07/the-future-development-of-oral-surgery-and-oral-medicine-services-in-wales.pdf (accessed June 2022).

British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. BAOMS: The Face of Surgery. Available at https://www.baoms.org.uk/#MainForm (accessed June 2022).

UK Government. The European Specialist Medical Qualifications Order 1995. 1995. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1995/3208/made (accessed June 2022).

General Dental Council. Consultation on the principles of specialist listing. 2019. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/default-source/consultations-and-responses/consultation-on-the-priciples-of-specialist-listing.pdf?sfvrsn=a5f84efa_2 (accessed June 2022).

General Medical Council. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Curriculum. 2021. Available at https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/oral---maxillofacial-surgery-curriculum-2021---minor-changes-approved-feb22_pdf-89626494.pdf (accessed June 2022).

Tannyhill R J 3rd, Baron M, Troulis M J. Do Graduating Oral-Maxillofacial Surgery Residents Feel Confident in Practicing the Full Scope of the Specialty? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; 79: 286-294.

Tannyhill R J 3rd, Baron M. How Do Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Residency Program Directors Feel About Their Graduating Residents' Level of Competence? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; 79: 964-973.

Royal College of Surgeons of England. Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery Fellowships. Available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/education-and-exams/accreditation/rcs-senior-clinical-fellowship-scheme/national-surgical-fellowship-scheme-register/oral-and-maxillofacial-surgery-fellowships/ (accessed June 2022).

Health Education England West Midlands. OMFS Training Programme. Available at https://www.westmidlandsdeanery.nhs.uk/postgraduate-schools/-surgery/omfs/training-programme (accessed June 2022).

General Dental Council UK. Dental Specialty Training. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/education-cpd/quality-assurance/dental-specialty-training (accessed June 2022).

Office for National Statistics. Living longer: how our population is changing and why it matters. 2018. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13 (accessed June 2022).

Kingston A, Robinson L, Booth H, Knapp M, Jagger C. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 2018; 47: 374-380.

Kingston A, Comas-Herrera A, Jagger C, MODEM project. Forecasting the care needs of the older population in England over the next 20 years: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2018; DOI: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30118-X.

NHS England. Managed Clinical Networks. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/info-professional/dental/dcis/south-west-ldn/mcn/ (accessed June 2022).

Rooney E. The evolution of dentists with enhanced skills. Faculty Dent J 2015; 6: 66-69.

Ghotane S G, Harrison V, Radcliffe E, Jones E, Gallagher J E. Enhanced skills in periodontology: evaluation of a pilot scheme for general dental practitioners and dental care professionals in London. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 700-707.

Eliyas S, Briggs P, Gallagher J E. The experience of dentists who gained enhanced skills in endodontics within a novel pilot training programme. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 269-275.

Radcliffe E, Ghotane S G, Harrison V, Gallagher J E. Interprofessional enhanced skills training in periodontology: a qualitative study of one London pilot. BDJ Open 2017; 3: 17001.

Ghotane S G, Al-Haboubi M, Kendall N, Robertson C, Gallagher J E. Dentists with enhanced skills (Special Interest) in Endodontics: gatekeepers views in London. BMC Oral Health 2015; 15: 110.

Montgomery-Cranny J, Edmondson M, Reid J, Eapen-Simon S, Hegarty A M, Mighell A J. Development of a managed clinical network in oral medicine. Br Dent J 2017; 223: 719-725.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following colleagues who helped with data collection and presentations at local audit and clinical governance groups: Merthyr Tydfil - Dr Melanie Simms; Newport - Dr Bridie Griffiths and Dr Aled Griffiths; Bath - Dr Nicola Gradwell; Plymouth - Dr Yen Lin, Dr Susanna Carr and Dr Edward Brocklebank; Taunton - Dr John Watt, Dr Ruman Dhillon, Dr Helen Walker and Dr Zahra Omran; Torbay - Dr Tobias Topliss, Dr Magdalena Chan and Dr Danielle Brown; Truro - Dr Zohaib Ahmed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yen M. Lin: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing, and visualisation. Melanie L Simms: writing - review and editing, and visualisation. Phil A. Atkin: conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resources, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing, visualisation, supervision, and project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Given that the study was a service evaluation to determine demand for development of specialist services approved by local Clinical Governance groups in each DGH, formal approval from an ethics committee was not required.

Data were collected retrospectively so consent to participate was not required.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2023

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Simms, M. & Atkin, P. Oral medicine in regional oral and maxillofacial surgery units: a five-year review. Br Dent J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5691-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5691-2

This article is cited by

-

Oral mucosal disease: dilemmas and challenges in general dental practice

British Dental Journal (2024)

-

Provision of oral medicine in Scottish oral and maxillofacial surgery units: where are we and where are we going?

British Dental Journal (2024)