Abstract

Direct arylation polymerization (DArP) offers a streamlined alternative to Stille coupling for synthesizing π-conjugated donor–acceptor (DA) polymers by forming C–C bonds through formal C–H/C–X coupling, eliminating the need for toxic organotin reagents. Early DArP systems often failed to achieve both high molecular weight and low defect levels because of insufficient catalyst efficiency and selectivity. This Focus Review summarizes the development of highly efficient and selective palladium catalysts supported by the hemilabile phosphine P(2-MeOC6H4)3 (L1). L1 is used alone or with the coligands N,N,N′,N′‑tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) or 2‑dicyclohexylphosphino‑2′,4′,6′‑triisopropylbiphenyl (XPhos). L1 maintains reactive mononuclear Pd species for efficient C–H activation; TMEDA suppresses side reactions such as homocoupling and branching; and XPhos facilitates the oxidative addition of less reactive C–X bonds. These ligand systems enable high-molecular-weight polymers (number-average molecular weight up to 347,700, yields up to 100%) with well-defined structures (cross-coupling selectivity as high as >99%) across a broad monomer scope. Devices based on these materials deliver up to 9.9% power conversion efficiency in organic photovoltaics and hole mobilities ≥0.3 cm2·V–1·s–1 in organic thin-film transistors, comparable to those from Stille coupling. These advances firmly position DArP as a practical, tin-free platform for the precise synthesis of high-performance π-conjugated DA polymers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

π‑Conjugated donor–acceptor (DA) polymers underpin much of the current organic electronics. Combining donor and acceptor units enables control over the band gap, charge balance, and solid-state packing, allowing for high-performance organic photovoltaics (OPVs) [1], organic thin-film transistors (OTFTs) [2], and related devices [3]. These applications demand synthetic routes that deliver high-molecular-weight, compositionally precise polymers in a solution-processable form.

To meet these requirements, Stille cross-coupling polymerization has long been a mainstay for the synthesis of DA polymers because it couples monomers prefunctionalized with organotin groups in a highly reliable manner (Fig. 1A) [4, 5]. However, the preparation of these organotin monomers—often via multistep synthesis and purification—adds a significant synthetic burden. Moreover, the method generates stoichiometric amounts of toxic byproducts (e.g., SnMe3Br), raising environmental concerns. To address these issues, palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization (DArP) has emerged as a promising alternative for forming C–C bonds directly through C–H activation, thereby streamlining synthesis and eliminating the need for organotin reagents (Fig. 1A) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Although direct arylation for small-molecule synthesis is well established [14,15,16,17,18], its application to polymerization has proven challenging. In early DArP, limited catalyst efficiency and selectivity led to low molecular weight and structural defects, undermining functional performance (Fig. 1B; see Section “Requirements for Precision Polymer Synthesis by DArP” for details). To overcome these limitations, we developed palladium catalyst systems that enable the precise synthesis of DA polymers with performance comparable to that of Stille-derived materials.

This Focus Review traces the evolution of our catalyst design around three elements: P(2-MeOC6H4)3 (L1) for high efficiency, diamine coligands to enhance selectivity, and complementary phosphines for high efficiency with less reactive C–X bonds. These strategies broaden the monomer scope, improve both efficiency and selectivity, and enhance control over the polymer microstructure.

The following sections outline the mechanistic features underlying the efficiency and selectivity of DArP and then describe the development and scope of our catalyst systems, emphasizing the structure–property relationships in DA polymers.

Mechanistic basis and catalyst design principles of DArP

DArP is proposed to proceed via four elementary steps (Fig. 1C) [18]:

-

(i)

C–X bond activation: oxidative addition of an aryl halide (Ar–X) to a Pd(0) complex (C1) yields an aryl–Pd(II) halide (C2).

-

(ii)

Anionic ligand exchange: the halide in C2 is rapidly replaced by a carboxylate ligand to form a carboxylate–Pd(II) species (C3).

-

(iii)

C–H bond activation: from C3, C–H activation of heteroarenes (H–Ar′) occurs via a six-membered, carboxylate-assisted concerted metalation–deprotonation (CMD) transition state, yielding diaryl–Pd(II) complex C4. The CMD barrier decreases with increasing C–H acidity and π-electron density; greater acidity facilitates proton abstraction by the carboxylate, whereas higher electron density stabilizes Pd–C bond formation to the electrophilic Pd(II) center in the CMD transition state. Consequently, electron-rich heteroarenes such as thiophene undergo regioselective C2/C5 activation without directing groups, enabling linear 2,5-coupling to construct π-conjugated backbones.

-

(iv)

Reductive elimination: C4 undergoes reductive elimination to give the biaryl product (Ar–Ar′), regenerating Pd(0) (C1).

For efficient catalysis, ligands must balance electronic and steric demands across all steps: an electron-rich Pd(0) accelerates oxidative addition [19], while a slightly electron-poor Pd(II) lowers the CMD barrier [20]. Ligands must be bulky enough to stabilize reactive mononuclear Pd species but not so hindered as to block substrate binding; in many catalytic manifolds, increased steric demand can facilitate reductive elimination [21, 22]. This electronic and steric balance is essential for fast, regioselective coupling across diverse monomers. The Pd/L1 system exemplifies this balance: its hemilabile phosphine framework provides electronic tunability with moderate steric bulk, affording high reactivity and broad monomer compatibility, thereby establishing it as a robust platform for precision DArP.

For completeness, other DArP strategies—such as premetalation with strong bases (e.g., Grignard reagents) [23, 24] or dual-metal (Pd/Cu, Pd/Ag) systems [25, 26]—are noted but not described in detail here, as this Review focuses on CMD-type activation.

Requirements for precision polymer synthesis by DArP

Two criteria are critical for the precise synthesis of π-conjugated polymers via DArP:

-

(1)

High-Molecular-Weight. DArP proceeds via a step-growth mechanism; therefore, the molecular weight follows the Carothers equation: DP = 1/(1–p), where DP is the degree of polymerization and p is the degree of monomer conversion. Accordingly, achieving a high molecular weight requires a catalyst that enables near-quantitative conversion while maintaining the solubility of the growing chains.

-

(2)

Rigorous Structural Control. Side reactions—such as homocoupling (causing sequence errors) or nonselective C–H activation at undesired positions (e.g., C3 or C4 of thiophene)—introduce irreversible defects (Fig. 1B). These defects degrade electronic properties [27, 28] and, through branching or cross‑linking, can render the polymer insoluble and unusable in device fabrication. Therefore, catalysts must achieve exceptionally high selectivity to suppress these pathways.

Our studies show that judicious selection of ligands and solvents is essential for balancing efficiency and selectivity. The following sections illustrate how these factors were applied in the development of highly efficient and selective Pd catalyst systems for precision DArP.

Comparison of Fagnou-type and Pd/L1 catalysts

To achieve both high molecular weight and minimal defects, two representative palladium catalysts dominate DArP: Fagnou‑type conditions and Pd/L1-based systems. Both employ a carbonate base and a carboxylic acid additive (often tBuCO2H) to promote CMD-type C–H activation but differ markedly in ligand architecture and solvent compatibility.

-

(1)

Fagnou-Type Conditions. Originally developed by Fagnou for small-molecule C–H arylation [29], these conditions typically employ Pd(OAc)2 with bulky trialkylphosphines PR3 (e.g., PCy3 and PtBu2Me) in polar amide solvents such as N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc). Their extension to polymer synthesis—most notably Kanbara’s DArP of 1,2,4,5‑tetrafluorobenzene [12]—demonstrated that tin‑free cross‑coupling can produce π-conjugated alternating copolymers [10]. Under these conditions, the substrate class dictates the solvent/ligand regime; heteroarenes with acidic C–H bonds (e.g., 1,2,4,5‑tetrafluorobenzene) and electron-rich thiophenes (e.g., 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) react readily in DMAc but stall in toluene [30, 31]. In polar amides, competitive amide coordination is well documented; catalytically competent amide-ligated Pd species form even in the presence of PR3 [32], which is consistent with the high reactivity in DMAc. In contrast, electron-deficient monomers such as thienopyrroledione (TPD) couple efficiently in toluene, where PR3 ligation is maintained, but show little or no reactivity in DMAc [30, 31]. These contrasting trends indicate that solvent effects reflect both catalyst speciation (amide- vs. PR3-ligated Pd) and the match between catalyst form and the rate-determining step. In addition to these substrate-dependent effects, coordinating polar media such as DMAc can promote CMD, yet their poor solubility for many DA polymers often limits the molecular weight and increases structural defects [6, 33, 34]. In contrast, low-polarity, polymer-solubilizing media support a higher molecular weight when catalysis remains efficient.

-

(2)

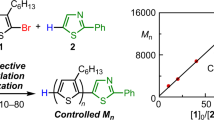

Pd/L1-based Systems. To overcome these challenges, we developed a complementary system based on Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (dba: dibenzylideneacetone) and P(2-MeOC6H4)3 (L1) (Fig. 2) [9]. The use of ancillary ligands such as TMEDA or XPhos further suppresses side reactions and enhances monomer compatibility.

Selected examples from the substrate scope of DArP with Pd/L1‑based catalysts. Representative polymerizations of X–Ar–X (red) with H–Ar′–H (blue) using L1 alone, L1 + TMEDA, or L1 + XPhos. Standard conditions: Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (1–2 mol% Pd), L1 (Pd/L1 = 1/1–2), with or without coligands [TMEDA (Pd/L1/TMEDA = 1/2/10–30) or XPhos (Pd/L1/XPhos = 1/2/2)], tBuCO2H (1 equiv), Cs2CO3 (3 equiv), THF or toluene at 100–110 °C for 24–120 h. The Mn and Đ were determined by GPC (polystyrene standards) in o-Cl2C6H4 at 140 °C; homocoupling defect levels were estimated by 1H NMR in C2D2Cl4 at 130 °C or o‑Cl2C6D4 at 140 °C. *Values were determined by GPC (polystyrene, THF, 40 °C). **Reactions run with PdCl2(NCMe)2 in place of Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3. Side‑chain definitions: R1 = 2‑ethylhexyl; R2 = 2‑hexyldecyl; R3 = 2‑octyldodecyl; R4 = 2‑decyltetradecyl

Rather than treating the Fagnou-type and Pd/L1 systems as mutually exclusive, their comparison clarifies design priorities. In the next section, we analyze the polymerization outcomes and mechanistic features for each Pd/L1-based mode. All the polymers discussed (P1–P16) are shown in Fig. 2 along with their outcomes under Pd/L1 catalysis, and key data—including ligand effects and comparisons with Stille and Fagnou-type conditions—are summarized in Table 1. This dataset serves as the basis for discussing design principles specific to the Pd/L1 platform.

DArP catalyzed by Pd/L1-based catalysts

Catalytic behavior and selectivity of Pd/L1

The Pd/L1 system exhibits high efficiency and selectivity in low-polarity, polymer-solubilizing solvents such as tetrahydrofuran (THF) and toluene. This system is compatible with a broad range of donor- and acceptor-type monomers, enabling the synthesis of high-molecular-weight polymers with low structural defect levels (Fig. 2) [35,36,37]. For example, P1 was obtained by polymerizing dibromofluorene with 1,2,4,5‑tetrafluorobenzene using Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3/L1/tBuCO2H/Cs2CO3 in THF (1 mol% Pd, Pd/L1 = 1/2), yielding a number-average molecular weight (Mn = 347,700) that was more than eleven times greater than that under Fagnou-type conditions (entries 1 and 2; Table 1) [35]. Replacing tBuCO2H with MeCO2H gave similar results, and comparable Mn values were also achieved in toluene, confirming catalytic efficiency in low-polarity media (runs 1–3; Table 2).

Ligand screening underscores the unique effectiveness of L1 (Table 2) [35]. Substituting PCy3, PtBu2Me, or Buchwald-type ligands (e.g., XPhos and SPhos) gave Mn < 10,000 (runs 4–8). Even phosphines with fewer ortho-methoxy substituents than L1 showed reduced performance: PPh(2-MeOC6H4)2 gave Mn = 31,300, while PPh3 gave Mn < 10,000 (runs 9–10). P(2-Me2NC6H4)3 gave no polymer, and both P(2-MeC6H4)3 and P(4-MeOC6H4)3 yielded Mn values less than 10,000 (runs 11–13). These results highlight the crucial electronic and steric roles of the ortho substituents of L1.

The Pd/L1 system also polymerizes electron-deficient monomers such as TPD and thiophene-flanked thiazolothiazoles to yield P2–P7 (Fig. 2) [36, 37]. The molecular weight distribution of these polymers was highly solvent sensitive. P2 synthesized in THF showed a monomodal profile, whereas the same polymer synthesized in DMAc under Fagnou-type conditions exhibited a bimodal distribution skewed toward lower Mn (36,800 vs. 15,100; entries 3 and 4, Table 1). Improved solubility in L1/THF likely suppresses premature termination, yielding more uniform, higher molecular weights. In addition to the choice of solvent, the nature of the Pd precursor also influenced the Mn: for P2, a Mn of 25,500 was achieved with Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3, which increased to 36,800 with PdCl2(NCMe)2. P3 and P4, tested only with PdCl2(NCMe)2, showed similarly high Mn values, confirming the benefit of this precursor [36]. A recent study by another group further demonstrated that well-defined palladacycle precatalysts can increase Mn levels, emphasizing the importance of precursor selection [38].

Relative to Stille cross-coupling, Pd/L1 delivers a higher Mn and fewer defects (e.g., P5: Mn 42,200, <2% homocoupling vs. Stille Mn 21,800, 4.3%) (entries 5 and 6; Table 1) [37]. In the Stille process, methyl migration from SnMe3-substituted monomers limits chain growth and introduces defects. Direct comparisons indicate a practical advantage of Pd/L1 for precision polymer synthesis under the tested conditions.

Taken together, these results support Pd/L1 as a versatile, reliable DArP catalyst under low-polarity conditions. With broad monomer scope, high efficiency, and low defect levels, Pd/L1 is now recognized as a benchmark platform in the field [6,7,8].

Mechanistic insights into enhanced reactivity

To probe the origin of Pd/L1 reactivity, we isolated aryl‑palladium(II) carboxylate complexes [PdAr(O2CR)(L)] (Fig. 3; C3; Ar = Ph, R = Me in this study; L = L1, PPh3) [39, 40]. Among these, mononuclear species with bidentate carboxylate ligation [PdAr(O₂CR-κ²O)(L)] (C3-κ²O) are considered catalytically competent for C–H activation [17, 18], yet are coordinatively unsaturated and prone to aggregation. For example, the PPh3 complex was isolated as a dinuclear species, [PdPh(µ2-O2CMe)(PPh3)]2 (C3b2), which remained aggregated in solution, with little to no formation of the mononuclear complex (C3b-κ²O). In contrast, the L1 analog, although dinuclear in the solid-state (C3a2), dissociated in solution into a dynamic equilibrium between mononuclear species: a κ2-PO complex (C3a-κO; monodentate carboxylate) and a κP complex with a bidentate carboxylate ligand (C3a-κ²O), the latter representing the catalytically active species [17, 18]. This dynamic coordination mode of L1 suppresses aggregation and sustains a reactive mononuclear population, unlike the persistent dimeric form of the PPh3 complex.

Structures and reactivities of phenyl-palladium(II) carboxylate complexes bearing L1 and PPh3. *IR absorbance ratios of the νasym(CO2) bands assigned to bridging acetato ligands (μ2‑O2CMe; μ1‑O2CMe), monodentate acetato (O2CMe‑κO), and bidentate/chelating acetato (O2CMe‑κ2‑O,O) in CD2Cl2 at room temperature. **Yields of the direct arylation product (2-methyl-5-phenylthiophene)

This structural observation offers a plausible explanation for the higher reactivity of the L1 complex in direct arylation (Fig. 3): the L1 complex reacts with 2-methylthiophene in THF with a pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobsd) nearly an order of magnitude greater than that of the PPh3 complex. Moreover, the reactivity of the L1 complex remains consistent across THF, toluene, and DMAc, whereas the PPh3 complex shows strong solvent dependence—high in DMAc but low in low-polarity media—highlighting the advantage of L1 in polymer-solubilizing, low-polarity environments.

The acceleration observed with L1 also appears to arise from its ability to generate Pd(II) centers of moderate electrophilicity, which favor CMD‑type C–H activation. In contrast, strongly electron-donating ligands reduce Pd electrophilicity and disfavor CMD. In support of this, a Pd-XPhos complex—typical of electron-rich phosphines—exhibited more than 20-fold lower reactivity toward 2-methylthiophene than the L1 analog did [41].

Collectively, the superior performance of Pd/L1 in DArP stems from its hemilabile coordination, which stabilizes mononuclear Pd species, suppresses aggregation, and minimizes solvent sensitivity, and from its balanced electronic properties, which promote efficient CMD. Together, these features enable selective polymerization under practical, low-polarity conditions.

Highly selective mixed-ligand catalysts

Monomers bearing multiple reactive C–H sites (bolded in Fig. 2) are prone to indiscriminate activation, causing branching and cross-linking. However, these C–H sites often confer advantages—low steric hindrance and intramolecular heteroatom–H interactions—that promote backbone planarity and extended π-conjugation, thereby enhancing charge transport [42]. This trade-off complicates monomer design. Although structural modification can suppress side reactions, the electronic or optical properties are often compromised. To address this trade-off without altering the monomer, we developed a mixed-ligand catalyst that combines L1 with TMEDA, which directs selective arylation while suppressing side reactions [43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Suppression of insolubilization and homocoupling

The benefit of TMEDA was first demonstrated in the DArP synthesis of P8 (entries 7 and 8; Table 1) [43, 44]. Under standard conditions (Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3/L1/tBuCO2H/Cs2CO3 in toluene), the product was mostly insoluble (74%), and the soluble fraction contained substantial defects. Adding TMEDA (Pd/L1/TMEDA = 1/2/10) afforded a fully soluble polymer in 88% yield, reducing homocoupling from 4.9% to 1.0% and increasing the Mn from 14,900 to 24,500. Similar improvements were observed for diketopyrrolopyrrole-based DA polymers P9 and P10 (entries 9 and 10, Table 1), where TMEDA suppressed insolubilization and structural defects [44]. This effect is illustrated by the 1H NMR spectra of P9 (Fig. 4A). Without TMEDA (Fig. 4A-a), the polymer exhibited intense signals from homocoupling (B and C; 12.5%) and branching (D) and was partly insoluble. With TMEDA (Fig. 4A-b), homocoupling was reduced to 1.6%, branching disappeared, and the Mn increased from 3,100 to 24,500—likely by suppressing Ar–X → Ar–H reduction, a chain-terminating side reaction.

Suppression of defect formation by TMEDA. A 1H NMR spectra of P9 obtained with (a) Pd/L1 and (b) Pd/L1 + TMEDA (C2D2Cl4, 130 °C, 800 MHz). B Proposed cascade leading to homocoupling and branching. C Proposed catalytic cycles: productive cross‑coupling via the cis-route, and Ar–X reduction → Ar′–Ar′ homocoupling via the trans-route in DArP

Side-reaction pathways and suppression mechanism

Product analysis revealed a cascade pathway (Fig. 4B) [43,44,45]: (a) reduction of Ar–X to Ar–H with concomitant homocoupling of H–Ar′ to Ar′–Ar′; (b) coupling of accumulated Ar–H with Ar–X to give Ar–Ar; and (c) branching and cross-linking. Similar pathways have been reported by others [50], supporting the generality of this cascade side reaction. TMEDA plausibly suppresses this cascade by intercepting the initial step (a).

Catalytic cycle and site-selective C–H activation

On the basis of these results, we propose the catalytic cycle shown in Fig. 4C, differentiating productive and unproductive pathways involving aryl-Pd(II) carboxylate (C3) [44, 50]. In this intermediate, CMD-type C–H activation can occur at either the cis or trans position relative to the aryl ligand (cis and trans route).

In the cis route, CMD yields cis‑C4, which undergoes reductive elimination to give Ar–Ar′. In the trans route, CMD yields trans-C4, which resists reductive elimination and instead undergoes protonolysis—the microscopic reverse of CMD—forming Ar–H and Pd–Ar′ (C3homo), which may react further to form homocoupling defects (Ar′–Ar′). Both the cis and trans routes are supported as accessible by independent DFT studies [50].

Accordingly, we hypothesize that TMEDA selectively blocks the trans route. In the trans configuration, TMEDA may coordinate to Pd (trans-C4TMEDA) and compete with the carboxylate in deprotonating the C–H bond, suppressing trans‑C–H activation. In contrast, in the cis configuration (cis-C4TMEDA), TMEDA remains trans to the substrate and is uninvolved in CMD. Such site-selective blocking likely explains why monoamines such as trimethylamine, which lack bidentate coordination, are ineffective [44].

Scope expansion and selectivity tuning in Pd/L1–TMEDA catalysis

Pd/L1 + TMEDA is applicable to diverse monomers. For example, the polymerization of 2,2′-bithiophene (BT), which typically suffers from extensive branching under Fagnou-type conditions [34], proceeds cleanly to yield P11 (Mn 43,800) with no insoluble byproducts [47]. Similarly, dithienylethene (DTE) and 2,6-di(5-thienyl)benzodithiophene (DTBDT) give P12 and P13 with 98– > 99% selectivity and a Mn up to 31,500 [46, 48, 49]. These high-performance OTFT/OPV polymers, previously accessible only via Stille coupling [51,52,53], can now be obtained by DArP. This advance is particularly significant given the prominence of DTBDT-based OPV materials [54]. Device metrics for these materials appear in Section “Device Performance of Defect-Suppressed Polymers”.

The general benefit of TMEDA in DArP has been confirmed by other groups [55,56,57], although this benefit varies with the steric and electronic properties of the monomer [58, 59]. Therefore, for optimal performance, tailoring the ligand set to each monomer class remains essential. Complementary strategies reported by other groups include steric tuning of L1 (e.g., cycloheptyloxy in place of methoxy) [60] or modification of the carboxylic acid (e.g., neodecanoic acid in place of tBuCO2H) [61, 62]. Such fine-tuning of steric and electronic parameters may further expand the Pd/L1 platform to otherwise incompatible monomers.

Highly efficient mixed-ligand catalysts

Conventional DArP catalysts perform well with aryl bromides and iodides but are generally ineffective toward more abundant and less expensive aryl chlorides. This limitation arises because no single ligand efficiently promotes both key rate‑determining steps: oxidative addition of the C–Cl bond and CMD-type C–H bond activation. As discussed in Section “Mechanistic Basis and Catalyst Design Principles of DArP”, electron-rich phosphines, including Buchwald-type ligands (e.g., XPhos, tBuXPhos, and BrettPhos), accelerate C–Cl oxidative addition [63]. In contrast, the less σ-donating, hemilabile ligand L1 facilitates C–H activation.

This trade-off is effectively addressed by a mixed-ligand strategy: combining L1 and XPhos (Pd/L1/XPhos = 1/2/2) [41]. Whereas previous DArP methods for aryl chlorides required Pd/Cu dual catalysis with Cu(I) salts [26], our Cu-free system enables efficient synthesis of DA polymers P14–P16 (Mn up to 191,000, selectivity > 99%) (Fig. 2). Control experiments revealed that neither L1 nor XPhos alone yielded high-Mn polymers under identical conditions; instead, only low-conversion oligomers were obtained. Notably, P16—known for its high solar-cell performance [64]—was synthesized directly from inexpensive p-dichlorobenzene.

Mechanistic studies support a step-specific synergy between L1 and XPhos (Fig. 5A). C–Cl oxidative addition of chlorobenzene to Pd(0) proceeds ~20 times faster with XPhos than with L1 (C1L1 vs. C1XPhos), while C–H bond activation of 2-methylthiophene is ~15 times faster with L1 than with XPhos (C3L1 vs. C3XPhos). 31P NMR reveals rapid ligand exchange, with equilibria of Pd(0) and Pd(II) species bearing both ligands (C1L1:C1XPhos = 30:70; C3L1:C3XPhos = 47:53). These observations indicate frequent ligand exchange during catalysis, allowing each step to proceed in its optimal ligand environment (Fig. 5B). XPhos, a strong σ-donor and “soft” κ2‑P,π chelate (phosphorus plus biphenyl π system), stabilizes the soft Pd(0) center, promoting C–Cl oxidative addition. After this step, steric congestion reduces XPhos affinity, enabling ligand relay to L1. L1, which coordinates in a κ2‑P,O mode via its hard methoxy oxygen and phosphorus, is well suited to stabilize the harder Pd(II) center and facilitate CMD. This dynamic ligand relay enables efficient, selective coupling of aryl chlorides.

Step‑specific ligand synergy and dynamic relay. A Plausible pathway for direct arylation with an aryl chloride under the mixed‑ligand catalyst. *Relative activities were estimated from pseudo‑first‑order rate constants for the reactions of [Pd(dba)(L)n] (L = XPhos, n = 1; L = L1, n = 2) with chlorobenzene and [PdPh(O2CMe)(L)] (L = XPhos or L1) with 2‑methylthiophene in THF‑d8 at 60 °C. **Determined by 31P NMR: THF-d8 for [Pd(dba)(L)n] (L = XPhos, n = 1; L = L1, n = 2) and CD2Cl2 for [PdPh(O2CMe)(L)] (L = XPhos or L1) at 25 °C. B Crystal structures of representative complexes [Pd(dba)(XPhos)] (C1XPhos; CCDC 2254607) and [Pd(2,6-Me2C6H3)(O2CMe)(L1)] (C3L1; CCDC 1046469)

In contrast to XPhos, related ligands such as tBuXPhos and BrettPhos failed to support efficient catalysis under otherwise identical conditions, highlighting the need for a finely tuned steric and electronic profile. Although the proposed mechanism is well supported by experimental evidence (Fig. 5), further studies could refine our understanding of intermediate speciation and ligand dynamics. This mechanistic insight underpins the broader significance of the present work, which provides one of the most thoroughly characterized examples of a mixed-ligand catalyst achieving high performance through step-specific ligand roles. Given the limited mechanistic understanding of mixed-ligand catalysis [65,66,67], our findings may offer valuable guidance for future catalyst design.

Device performance of defect-suppressed polymers

High-selectivity DArP can deliver polymers with device metrics comparable to those from conventional cross-coupling (Fig. 6; entries 11–17; Table 1). All the polymers were treated with diethyldithiocarbamate to minimize residual palladium, as residual Pd above ~102 ppm is known to reduce the power conversion efficiency (PCE) in OPVs [68]. In a representative case, the residual Pd content in the polymer decreased from >1500 ppm to 11–60 ppm, with ~90% polymer recovery [45].

Device performance of defect-suppressed DA polymers synthesized by DArP compared with Stille coupling. (1) OPV performance of P11/PC71BM: J–V curves (a) and external quantum efficiency (EQE) spectra (b) show that TMEDA suppresses branching and restores OPV efficiency to Stille levels. (2) OPV performance of P13/ITIC: Despite large differences in homocoupling, the PCE remains unaffected, indicating defect-tolerant behavior. The J–V curves (c) and EQE spectra (d) are nearly identical for both methods. (3) OTFT performance of P12: Transfer curves for DArP (e) are cleaner than those for Stille coupling (f), whose double-slope profile indicates trap-limited transport likely arising from subtle backbone irregularities (VD = drain voltage, ID = drain current, and VG = gate voltage). ITIC and PC71BM refer to typical fullerene and nonfullerene acceptors, respectively

DA polymer P11, which is based on unsubstituted BT, provides a performance benchmark (Fig. 6A, B) [47]. DArP using Pd/L1 gave a Mn = 47,600 but a limited PCE (8.0 ± 0.1%) in bulk-heterojunction (BHJ) OPVs with PC71BM, which is consistent with the defect-induced shortening of effective conjugation and increased energetic disorder, degrading charge transport. In contrast, Pd/L1 + TMEDA afforded P11 (Mn = 43,800) free of branching, achieving PCEs up to 9.0 ± 0.1% (best 9.2%), which are comparable to those of the Stille analogs (9.3 ± 0.2%, best 9.8%) under identical device architectures.

In contrast to P11, the DTBDT-based polymer P13 showed high tolerance to structural defects [48]. The sample prepared with Pd/L1 + TMEDA had Mn = 31,500 and 2.0% homocoupling, versus 14.8% for the Stille counterpart. Despite this significant difference, BHJ devices with ITIC exhibited nearly identical PCEs (Figs. 6C, D); the DArP polymer averaged 9.5 ± 0.3% (the best was 9.9%), and the Stille polymer averaged 9.4 ± 0.1% (the best was 9.8%). This case illustrates that some systems are defect-tolerant; however, in many others, even minor homocoupling can severely impair device function [27].

Consistent with this general principle, our OTFT studies show that lowering the defect density improves charge transport [46]. For example, DTE-based P12 synthesized by DArP exhibited an average hole mobility of µh = 0.31 cm2·V–1·s–1, whereas the corresponding Stille polymer, despite a comparable average mobility (µh = 0.28 cm2·V–1·s–1), showed double-slope transfer curves, which are indicative of trap-limited transport (Fig. 6E, F) [69]. Both polymers showed no detectable homocoupling peaks by 1H NMR; however, unassigned minor peaks in the Stille-derived sample suggest subtle backbone irregularities that may account for the observed differences in charge transport.

Beyond defect consideration, the highest reported device metrics—up to 16.4% PCE in BHJ OPV and ambipolar OTFT mobilities (µe/µh = 5.86/3.40 cm2·V–1·s–1) [70, 71],—were achieved using fluorinated BT and DTE with Pd/L1 alone. This does not imply a limitation of TMEDA; rather, these monomers are inherently selective and undergo CMD cleanly without coligands. Applying TMEDA or related ligands to such monomers may further suppress rare defects and test the generality of selective DArP across more challenging backbones.

Collectively, these results show that advances in Pd/L1-based catalysis yield high-Mn, defect-suppressed DA polymers, broadening the scope of systematic structure–property studies and the translation of molecular design into high-performance devices.

Substrate scope and remaining challenges

The current Pd/L1-based catalysts exhibit high selectivity and broad substrate compatibility. They effectively couple a wide range of C–H substrates, such as thiophenes (e.g., alkylthiophenes and EDOT), thiazoles (at the 5-position), and fluorinated arenes, as well as C–X electrophiles, including aryl iodides, bromides, and chlorides. These advances provide a solid foundation for the precise synthesis of π-conjugated polymers and underscore the robustness of modern catalyst systems.

Despite this breadth, notable gaps remain. The parent thiophene—although among the most widely used donor building blocks in conjugated-polymer design [1,2,3]—has not, to the best of the current knowledge, been demonstrated as the C–H partner in precision alternating DArP. Likely causes include C2/C5 equivalence, which promotes multisite activation and branching; intrinsically lower C–H activation reactivity relative to electron-rich thiophenes (e.g., EDOT); and practical volatility (bp ≈ 84 °C) at elevated temperatures (≳100 °C), which are often required for efficient DArP.

Thiazoles also present challenges; C2 arylation is often sluggish owing to N→Pd coordination, which results in the formation of a stable complex and increases the CMD activation barrier, thus slowing turnover [37, 72]. Similarly, benzothiadiazoles show low reactivity, and even in the rare cases where polymer formation is achieved, higher Pd loadings are typically needed [73], possibly because of coordination effects, although this has not been clearly reported. Such cases suggest that CMD may be highly sensitive to both electronic effects and inner-sphere coordination.

On the electrophile side, pseudohalides remain underutilized [74]. Among these, aryl triflates (X = CF3SO3) have begun to show workable reactivity in DArP, as recently demonstrated by our group [75]. In contrast, tosylates (X = 4-MeC6H4SO3), whose C–O bonds are strong, are even less reactive.

These limitations point to three major challenges for future DArP development: (i) enabling low-temperature C–H activation ( ≤ 80 °C) to accommodate volatile or intrinsically less-reactive partners (e.g., the parent thiophene); (ii) suppressing coordination-induced CMD retardation while enforcing positional selectivity in heteroarenes with multiple reactive sites (e.g., thiazoles, benzothiadiazoles); and (iii) activating strong C–X bonds under milder conditions, including pseudohalides (e.g., aryl triflates and aryl tosylates). Addressing these issues will require further optimization of ligand and additive systems, particularly through modulation of the speciation and reactivity of key intermediates. Step-specific ligand pairing, as in the L1/XPhos system, offers one promising route, with the added potential to reduce Pd loading below 0.1 mol%. Continued progress along these lines will be essential to fully realize the potential of DArP across diverse π-conjugated systems.

Conclusion

This Focus Review outlined the evolution of DArP catalysts centered on the Pd/L1 platform, identifying three main regimes: L1 alone (effective when CMD proceeds cleanly), L1 + TMEDA (suppresses branching via site-selective activation), and L1 + XPhos (facilitates C–Cl oxidative addition). Together, these systems deliver a high Mn (up to ~3.5 × 105), >99% selectivity, and efficient performance at ≤2 mol% Pd. For the benchmark systems examined here, the device data show PCEs approaching 10% and hole mobilities >0.30 cm2·V–1·s–1, which are comparable to those of Stille-prepared analogs but without tin waste.

Continued progress in highly selective DArP catalysts not only enables the synthesis of defect-suppressed π-conjugated polymers but also improves the accuracy of structure–property studies by reducing synthetic variability—an essential factor in establishing well-defined correlations between molecular architecture and optoelectronic function.

Catalyst systems that combine exceptional site- and regioselectivity with efficient turnover—potentially including those enabling catalyst-transfer polymerization (CTP)—could offer additional control over molecular weight and chain-end fidelity [76]. Although CTP is well established in conventional cross-coupling under mild conditions [77, 78], its extension to DArP remains limited [79], mainly owing to the harsher conditions required for C–H activation. This barrier could be overcome through targeted advances in ligand design.

Taken together, these findings show that rational ligand design has addressed the long-standing limitations of DArP, positioning DArP as one of the benchmark methodologies for the precise synthesis of π-conjugated polymers.

References

Lee C, Lee S, Kim GU, Lee W, Kim BJ. Recent advances, design guidelines, and prospects of all-polymer solar cells. Chem Rev. 2019;119:8028–86.

Kim M, Ryu SU, Park SA, Choi K, Kim T, Chung D, et al. Donor–acceptor-conjugated polymer for high-performance organic field-effect transistors: a progress report. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;30:1904545.

Ding L, Yu ZD, Wang XY, Yao ZF, Lu Y, Yang CY, et al. Polymer semiconductors: synthesis, processing, and applications. Chem Rev. 2023;123:7421–97.

Carsten B, He F, Son HJ, Xu T, Yu L. Stille polycondensation for synthesis of functional materials. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1493–528.

Liang Z, Neshchadin A, Zhang Z, Zhao FG, Liu X, Yu L. Stille polycondensation: a multifaceted approach towards the synthesis of polymers with semiconducting properties. Polym Chem. 2023;14:4611–25.

Rudenko AE, Thompson BC. Optimization of direct arylation polymerization (DArP) through the identification and control of defects in polymer structure. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2015;53:135–47.

Bura T, Blaskovits JT, Leclerc M. Direct (hetero)arylation polymerization: trends and perspectives. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:10056–71.

Pouliot JR, Grenier F, Blaskovits JT, Beaupré S, Leclerc M. Direct (hetero)arylation polymerization: simplicity for conjugated polymer synthesis. Chem Rev. 2016;116:14225–74.

Wakioka M, Ozawa F. Highly efficient catalysts for direct arylation polymerization (DArP). Asian J Org Chem. 2018;7:1206–16.

Kuwabara J, Kanbara T. Facile synthesis of π-conjugated polymers via direct arylation polycondensation. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2019;92:152–61.

Wang Q, Takita R, Kikuzaki Y, Ozawa F. Palladium-catalyzed dehydrohalogenative polycondensation of 2-bromo-3-hexylthiophene: an efficient approach to head-to-tail poly(3-hexylthiophene). J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11420–1.

Lu W, Kuwabara J, Kanbara T. Polycondensation of Di-bromofluorene analogues with tetrafluorobenzene via direct arylation. Macromolecules. 2011;44:1252–5.

Berrouard P, Najari A, Pron A, Gendron D, Morin PO, Pouliot JR, et al. Synthesis of 5-Alkyl[3,4-c]thienopyrrole-4,6-dione-based polymers by direct heteroarylation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2068–71.

Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Aryl–Aryl bond formation by transition-metal-catalyzed direct arylation. Chem Rev. 2007;107:174–238.

Satoh T, Miura M. Catalytic direct arylation of heteroaromatic compounds. Chem Lett. 2007;36:200–5.

Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. Direct transition metal-catalyzed functionalization of heteroaromatic compounds. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1173–93.

Campeau LC, Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Recent advances in intermolecular direct arylation reactions. Aldrichimica Acta. 2007;40:35–41.

Ackermann L, Vicente R, Kapdi AR. Transition-metal-catalyzed direct arylation of (hetero)arenes by C–H bond cleavage. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9792–826.

Anjali BA, Suresh CH. Interpreting oxidative addition of Ph–X (X = CH3, F, Cl, and Br) to monoligated Pd(0) catalysts using molecular electrostatic potential. ACS Omega. 2017;2:4196–206.

Wakioka M, Nakamura Y, Hihara Y, Ozawa F, Sakaki S. Effects of PAr3 ligands on direct arylation of heteroarenes with isolated [Pd(2,6-Me2C6H3)(μ-O2CMe)(PAr3)]4 complexes. Organometallics. 2014;33:6247–52.

Mann G, Shelby Q, Roy AH, Hartwig JF. Electronic and steric effects on the reductive elimination of diaryl ethers from palladium(II). Organometallics. 2003;22:2775–89.

Engle KM, Yu JQ. Developing ligands for palladium(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization: intimate dialogue between ligand and substrate. J Org Chem. 2013;78:8927–55.

Mohr Y, Ranscht A, Alves-Favaro M, Quadrelli EA, Wisser FM, Canivet J. Nickel-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization for the synthesis of thiophene-based cross-linked polymers. Chem Eur J. 2023;29:e202202667.

Shibuya Y, Mori A. Dehalogenative or deprotonative? the preparation pathway to the organometallic monomer for transition-metal-catalyzed catalyst-transfer-type polymerization of thiophene derivatives. Chem Eur J. 2020;26:6976–87.

Kuwabara J, Tsuchida W, Guo S, Hu Z, Yasuda T, Kanbara T. Synthesis of conjugated polymers via direct C–H/C–Cl coupling reactions using a Pd/Cu binary catalytic system. Polym Chem. 2019;10:2298–304.

Kim H, Yoo H, Kim H, Park JM, Lee BH, Choi TL. Low-temperature direct arylation polymerization for the sustainable synthesis of a library of low-defect donor−acceptor conjugated polymers via Pd/Ag dual-catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147:11886–95.

Hendriks KH, Li W, Heintges GHL, van Pruissen GWP, Wienk MM, Janssen RAJ. Homocoupling defects in diketopyrrolopyrrole-based copolymers and their effect on photovoltaic performance. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11128.

Lombeck F, Marx F, Strassel K, Kunz S, Lienert C, Komber H, et al. To branch or not to branch: C–H selectivity of thiophene-based donor–acceptor–donor monomers in direct arylation polycon-densation exemplified by PCDTBT. Polym Chem. 2017;8:4738–45.

Lafrance M, Fagnou K. Palladium-catalyzed benzene arylation: incorporation of catalytic pivalic acid as a proton shuttle and a key element in catalyst design. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16496–7.

Kuwabara J, Yamazaki K, Yamagata T, Tsuchida W, Kanbara T. The effect of a solvent on direct arylation polycondensation of substituted thiophenes. Polym Chem. 2015;6:891–5.

Kuwabara J, Fujie Y, Maruyama K, Yasuda T, Kanbara T. Suppression of homocoupling side reactions in direct arylation polycondensation for producing high performance OPV materials. Macromolecules. 2016;49:9388–95.

Tan Y, Hartwig JF. Assessment of the intermediacy of arylpalladium carboxylate complexes in the direct arylation of benzene: evidence for C−H bond cleavage by “Ligandless” species. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3308–11.

Osakada K, Yamamoto T. Transmetallation of alkynyl and aryl complexes of Group 10 transition metals. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;198:379–99.

Fujinami Y, Kuwabara J, Lu W, Hayashi H, Kanbara T. Synthesis of thiophene- and bithiophene-based alternating copolymers via Pd-catalyzed direct C–H arylation. ACS Macro Lett. 2012;1:67–70.

Wakioka M, Kitano Y, Ozawa F. A Highly efficient catalytic system for polycondensation of 2,7-dibromo-9,9-dioctylfluorene and 1,2,4,5-tetrafluorobenzene via direct arylation. Macromolecules. 2013;46:370–4.

Wakioka M, Ichihara N, Kitano Y, Ozawa F. A highly efficient catalyst for the synthesis of alternating copolymers with thieno[3,4-c]pyrrole-4,6-dione units via direct arylation polymerization. Macromolecules. 2014;47:626–31.

Wakioka M, Ishiki S, Ozawa F. Synthesis of donor–acceptor polymers containing thiazolo[5,4-d]thiazole units via palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization. Macromolecules. 2015;48:8382–8.

Mirabal RA, Buratynski JA, Scott RJ, Schipper DJ. A palladium precatalyst for direct arylation polymerization. Polym Chem. 2024;15:847–52.

Wakioka M, Nakamura Y, Wang Q, Ozawa F. Direct arylation of 2-methylthiophene with isolated [PdAr(μ-O2CR)(PPh3)]n complexes: kinetics and mechanism. Organometallics. 2012;31:4810–6.

Wakioka M, Nakamura Y, Montgomery M, Ozawa F. Remarkable ligand effect of P(2-MeOC6H4)3 on palladium-catalyzed direct arylation. Organometallics. 2015;34:198–205.

Wakioka M, Hatakeyama K, Sakai S, Seki T, Tada K, Mizuhata Y, et al. Mixed-ligand approach to palladium-catalyzed direct arylation of heteroarenes with aryl chlorides: controlling reactivity of catalytic intermediates via dynamic ligand exchange. Organometallics. 2023;42:3454–65.

Jackson NE, Savoie BM, Kohlstedt KL, Cruz MO, Schatz GC, Chen LX, et al. Controlling conformations of conjugated polymers and small molecules: the role of nonbonding interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10475–83.

Iizuka E, Wakioka M, Ozawa F. Mixed-ligand approach to palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization: synthesis of donor–acceptor polymers with dithienosilole (DTS) and thienopyrroledione (TPD) units. Macromolecules. 2015;48:2989–93.

Iizuka E, Wakioka M, Ozawa F. Mixed-ligand approach to palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization: effective prevention of structural defects using diamines. Macromolecules. 2016;49:3310–7.

Wakioka M, Takahashi R, Ichihara N, Ozawa F. Mixed-ligand approach to palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization: highly selective synthesis of π-conjugated polymers with diketopyrrolopyrrole units. Macromolecules. 2017;50:927–34.

Wakioka M, Yamashita N, Mori H, Nishihara Y, Ozawa F. Synthesis of a 1,2-dithienylethene-containing donor-acceptor polymer via palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization (DArP). Molecules. 2018;23:981.

Wakioka M, Morita H, Ichihara N, Saito M, Osaka I, Ozawa F. Mixed-ligand approach to palladium-catalyzed direct arylation polymerization: synthesis of donor–acceptor polymers containing unsubstituted bithiophene units. Macromolecules. 2020;53:158–64.

Wakioka M, Torii N, Saito M, Osaka I, Ozawa F. Donor−acceptor polymers containing 4,8-dithienylbenzo[1,2‑b:4,5‑b’]dithiophene via highly selective direct arylation polymerization. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2021;3:830–6.

Wakioka M, Yamashita N, Mori H, Murdey R, Shimoaka T, Shioya N, et al. Formation of trans-poly(thienylenevinylene) thin films by solid-state thermal isomerization. Chem Mater. 2021;33:5631–8.

Zhang X, Shi Y, Dang Y, Liang Z, Wang Z, Deng Y, et al. Direct arylation polycondensation of β‑fluorinated bithiophenes to polythiophenes: effect of side chains in C−Br monomers. Macromolecules. 2022;55:8095–105.

Kawashima K, Fukuhara T, Suda Y, Suzuki Y, Koganezawa T, Yoshida H, et al. Implication of fluorine atom on electronic properties, ordering structures, and photovoltaic performance in naphthobisthiadiazole-based semiconducting polymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:10265–75.

Shin J, Um HA, Lee DH, Lee TW, Cho MJ, Choi DH. High mobility isoindigo-based π-extended conjugated polymers bearing di(thienyl)ethylene in thin-film transistors. Polym Chem. 2013;4:5688–95.

Bin H, Gao L, Zhang ZG, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang C, et al. 11.4% Efficiency non-fullerene polymer solar cells with trialkylsilyl substituted 2D-conjugated polymer as donor. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13651.

Wei M, Perepichka DF. Benzodithiophene-based polymer donors for organic photovoltaics. J Mater Chem A. 2025;13:12785–807.

Chen N, Yang LJ, Chen Y, Wu Y, Huang XM, Liu H, et al. PBDB‑T accessed via direct C−H arylation polymerization for organic photovoltaic application. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2022;4:7282–9.

Hsu NSY, Lin A, Uva A, Huang SH, Tran H. Direct arylation polymerization of degradable imine-based conjugated polymers. Macromolecules. 2023;56:8947–55.

Lin A, Guio L, LeCroy G, Lo S, Sharif A, Wang Y, et al. Soft and stretchable thienopyrroledione-based polymers via direct arylation. Adv Electron Mater. 2024;2400756:1–12.

Ponder JF Jr, Chen H, Luci AMT, Moro S, Turano M, Hobson AL, et al. Activation: evaluation of a simpler and greener approach to organic electronic materials. ACS Mater Lett. 2021;3:1503–12.

Lei Y, Fu P, He Y, Zhu X, Dou B, Zheng H, et al. A steric hindrance strategy facilitates direct arylation polymerization for the low-cost synthesis of polymer PBDBT-2F and its application in organic solar cells. Polym Chem. https://doi.org/10.1039/d5py00371g (in press).

Bura T, Beaupré S, Légaré MA, Quinn J, Rochette E, Blaskovits JT, et al. Direct heteroarylation polymerization: guidelines for defect-free conjugated polymers. Chem Sci. 2017;8:3913–25.

Rudenko AE, Thompson BC. Influence of the carboxylic acid additive structure on the properties of poly(3-hexylthiophene) prepared via direct arylation polymerization (DArP). Macromolecules. 2015;48:569–75.

Dudnik AS, Aldrich TJ, Eastham ND, Chang RPH, Facchetti A, Marks TJ. Tin-free Direct C−H arylation polymerization for high photovoltaic efficiency conjugated copolymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15699–709.

Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Biaryl phosphane ligands in palladium-catalyzed amination. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6338–61.

van Franeker JJ, Heintges GHL, Schaefer C, Portale G, Li W, Wienk MM, et al. Polymer solar cells: solubility controls fiber network formation. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:11783–94.

Fan Y, Cong M, Peng L. Mixed-ligand catalysts: a powerful tool in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:2698–702.

Chen MS, Narayanasamy P, Labenz NA, White MC. Serial ligand catalysis: a highly selective allylic C–H oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6970–1.

Fors BP, Buchwald SL. A multiligand based Pd catalyst for C-N cross-coupling reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15914–7.

Bracher C, Yi H, Scarratt NW, Masters R, Pearson AJ, Rodenburg C, et al. The effect of residual palladium catalyst on the performance and stability of PCDTBT:PC70BM organic solar cells. Org Electron. 2015;27:266–73.

Phan H, Ford MJ, Lill AT, Wang M, Bazan GC, Nguyen TQ. Electrical double-slope nonideality in organic field-effect transistors. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28:1707221.

Zhang X, Zhang T, Liang Z, Shi Y, Li S, Xu C, et al. Direct arylation polycondensation-derived polythiophene achieves over 16% efficiency in binary organic solar cells via tuning aggregation and miscibility. Adv Energy Mater. 2024;14:2402239.

Gao Y, Zhang X, Tian H, Zhang J, Yan D, Geng Y, et al. High mobility ambipolar diketopyrrolopyrrole-based conjugated polymer synthesized via direct arylation polycondensation. Adv Mater. 2015;27:6753–9.

Wakioka M, Nakamura Y, Hihara Y, Ozawa F, Sakaki S. Factors controlling the reactivity of heteroarenes in direct arylation with arylpalladium acetate complexes. Organometallics. 2013;32:4423–30.

Zhang X, Gao Y, Li S, Shi X, Geng Y, Wang F. Synthesis of poly(5,6-difluoro-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole-alt-9,9-dioctyl-fluorene) via direct arylation polycondensation. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2014;52:2367–74.

Zhou T, Szostak M. Palladium-catalyzed cross-couplings by C–O bond activation. Catal Sci Technol. 2020;10:5702–39.

Sakai S, Hanamura H, Fujita R, Tada K, Wakioka M. Direct Arylation Polymerization of Heteroarene with Aryl Triflates. Preprints of the 74th Symposium on Macromolecules. The Society of Polymer Science, Japan; 2025. Abstract 3C07.

Wakioka M, Xu K, Taketani T, Ozawa F. Synthesis of head-to-tail regioregular poly(3-hexylthiophene)s with controlled molecular weight via highly selective direct arylation polymerization (DArP). Polym J. 2023;55:387–94.

Yokozawa T, Ohta Y. Transformation of step-growth polymerization into living chain-growth polymerization. Chem Rev. 2016;116:1950–68.

Berbigier JF, Varju B, Liu JT, Edward AK, Seferos DS. Horizons in catalyst-transfer polymerization research. Coord Chem Rev. 2025;538:216724.

Huang SL, Ye CC, Pan YN, Liu QY, Wang C, Xu. Li. Living direct arylation polymerization via C−H activation for the precision synthesis of polythiophenes and their block copolymers. Macromolecules. 2025;58:2357–65.

Acknowledgements

The author extends sincere thanks to Prof. Fumiyuki Ozawa (Kyoto University) for invaluable collaboration, insightful discussions, and generous support; to colleagues for their contributions to spectroscopy and device characterization; to JSR Corporation for a valued collaboration; and to the students and researchers whose careful experiments made this work possible. Editorial assistance from Dr. Rader S. Jensen (The Chemical Society of Japan) is also gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 24750088, 15K17855, 17K05883, 21K05167, and 24K08420).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wakioka, M. Development of highly efficient and selective catalysts for direct arylation polymerization (DArP). Polym J 58, 103–116 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01107-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01107-8