Abstract

Rare and typically severe motor speech disorders such as childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) and dysarthria affect about 1 in 1000 children. The genetic basis of these speech disorders is well-documented, with approximately 30% of children who undergo genomic testing receiving an explanatory genetic diagnosis. As more children with speech disorders are offered genetic testing, understanding parental views and experiences around genetic testing for their child is critical in providing effective pre- and post-test genetic counselling. This research explored parental attitudes, experiences, and perceived implications of pursuing genetic testing for their child with motor speech disorder. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 parents of children with CAS or dysarthria who had undergone exome sequencing. Eight parents had received a genetic diagnosis for their child and 12 received uninformative genetic test results. Interviews were transcribed verbatim, co-coded, and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Parents were highly motivated to pursue genetic testing for their child’s speech disorder due to the perceived personal, clinical, social, and financial utility in obtaining a genetic diagnosis. Regardless of testing outcome, parents experienced complex emotional responses in receiving their child’s genetic test results. Parents whose child received a genetic diagnosis reported improved access to funding and clinical care; however, they also hoped for ongoing informational, clinical, and peer support in navigating the uncertainty surrounding their child’s rare diagnosis. Conversely, parents who received uninformative genetic test results reported finding meaning in this test outcome, and used emotional-focused and problem-focused strategies to cope with their child’s continued diagnostic odyssey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Speech disorders are one of the most common subtypes of paediatric neurodevelopmental conditions, affecting approximately 1 in 20 preschool-aged children1. Of these children, most experience mild articulation or phonological delays that resolve over time2. However, about 1 in 1000 children develop severe motor speech disorders such as childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) and dysarthria3. These conditions are characterised by impaired speech movement planning, programming (CAS) or execution (dysarthria), and lead to poor speech accuracy and frequent communication breakdown4. This can result in lifelong impacts to the child’s psychosocial wellbeing, educational attainment, and future employment opportunities1,4. Motor speech disorders can be acquired in some cases, such as those seen after traumatic brain injury, brain tumour or stroke5,6,7. Yet, there is increasing evidence for a genetic aetiology in children with non-acquired forms of CAS, with many copy number variants identified and more than 30 genes implicated8,9,10. Collectively, it has been shown that around 30% of children with motor speech disorders who undergo genomic testing will receive a genetic diagnosis10,11,12,13.

Genetic testing in children presents many practical and ethical challenges14. In the context of motor speech disorders, some children may lack the cognitive ability to understand the implications of genetic testing15. Furthermore, in Australia, individuals below 18 years of age do not have the legal capacity to make their own health decisions16. Therefore, parents commonly act as medical decision-makers on behalf of their child, balancing the perceived utility of testing with the perceived best interest of the child. Healthcare professionals offering genetic testing in children need to have a thorough understanding of parental values, motivations, and concerns towards testing to ensure informed decision making by the child’s parents17. It is also imperative to understand parental experiences in receiving and coping with their child’s genetic test results, regardless of test outcome, as this informs the family’s subsequent support needs.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have evaluated parental views and experiences in pursuing genetic testing for any childhood speech or language disorders. However, research has shown that most parents have positive attitudes towards genetic testing for children with other neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism, intellectual disability, and epilepsy18,19,20,21. Common motivators for testing include the desire to end the child’s diagnostic odyssey, improving their clinical management, determining recurrence risk, psychological and emotional relief, and altruistic intentions to help others19,21,22. Literature also suggests that parental experiences in receiving and coping with their child’s genetic test results are complex and multifaceted, regardless of genetic testing outcome23,24,25.

While parents of children with motor speech disorders may have views and experiences that overlap with other neurodevelopmental conditions, there may be other unidentified information and support needs due to the unique challenges faced by children and families affected specifically by speech impairment. We aimed to address this research gap by exploring parental attitudes and experiences in pursuing genetic testing for children with motor speech disorders.

Methods

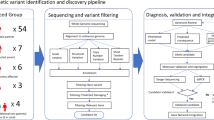

Sampling and recruitment

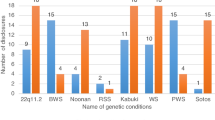

This was a single-site study conducted as part of the Genetics of Speech Disorders programme at the Murdoch’s Children Research Institute12,13. Children in this cohort had motor speech disorder as their primary area of developmental concern (as assessed by a speech pathologist and clinical geneticist), IQ > 70, no hearing impairment, and were aged 3–18 years at the time of initial recruitment. These families were systematically offered genomic testing following speech assessment and confirmation of a motor speech disorder diagnosis by a speech pathologist. Chromosomal microarray and Fragile X testing were always discussed and offered by a clinical geneticist as first-tier genetic investigations. Families were offered exome sequencing if there were no findings from these tests that explained the child’s presentation. Genomic testing results disclosure was facilitated by a clinical geneticist, speech pathologist, and/or genetic counsellor. This was conducted in-person or via teleconferencing for parents whose child received a genetic diagnosis, and via telephone for those who did not.

Individuals were eligible to participate in the present study if they were parents of a child who underwent exome sequencing after receiving negative chromosomal microarray and Fragile X results. To explore a breadth of parent experiences, we used purposive sampling26 to recruit both parents who received a genetic diagnosis for their child, as well as those who did not (hereafter referred to as uninformative genetic test results).

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by CA and YQL via Zoom27, using an interview guide which was developed based on comprehensive literature review and the study team’s clinical experience. Interview questions were designed to explore parental thoughts and experiences throughout the genetic testing process, such as their pre-test motivators and their reactions as well as coping strategies post-results disclosure (Supplementary File 1). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. To preserve participant confidentiality, all identifying information was removed during transcription and replaced by pseudonyms or generalised terms.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were managed using the QSR NVivo software28. Due to the lack of previous research in this area, we developed an in-depth understanding around the research topic by using reflexive thematic analysis to draw patterns and meaning from interview responses29,30. Codes were assigned to sections of analytic interest within the transcribed data, and the coding schema was refined after each successive interview transcription. All transcripts were coded by CA and YQL, and 25% co-coded by a third investigator (AJ) to ensure rigour. Related codes were organised and merged to generate overarching themes. Verbatim exemplar quotes were used to represent each theme (Supplementary File 2).

Reflexivity statement

At the time of this study, CA and YQL were final year genetic counselling students. CA had some experience completing quantitative research through undergraduate research programmes. She did not have any clinical genetics experience at the time of data collection. YQL had over two years of experience working in cancer genetics, both in clinical and research settings. AJ was a genetic counsellor with clinical paediatric and prenatal experience, as well as qualitative research experience. The coding investigators have no personal or family history of motor speech disorders. They also had no clinical role within the Genetics of Speech Disorders programme and had no prior contact with the research participants.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 20 female participants were interviewed, of whom 8 received a genetic diagnosis for their child and 12 received uninformative genetic test results. All participants had a child with a motor speech diagnosis of either CAS (n = 18), dysarthria (n = 1), or both (n = 1); and their child aged between 4;6 to 21;4 years at the time of interview. The median time interval between receiving their child’s genetic test results and interview participation was 11.5 months (Table 1).

Theme 1: parents were motivated to pursue genetic testing for their child

Overall, all participants expressed positive attitudes towards genetic testing for their child’s motor speech disorder. While some were initially worried about potential discoveries from the genetic test, these concerns were ultimately outweighed by their desire to be informed about their child’s condition.

“The desire to know and understand was more powerful, it was overwriting any fear that we had about what we might know” - Bella, uninformative result

Subtheme: finding an answer

Despite receiving a clinical diagnosis of motor speech disorder, participants felt that the aetiology of their child’s condition remained unknown. Therefore, a key motivator in pursuing genetic testing was to obtain a causal explanation for their child’s diagnosis. This perspective was often described alongside a desire to end their child’s diagnostic odyssey.

“I mean, we’ve been searching for so long that I think we were ready to find an answer” - Sophie, diagnostic result

Additionally, some participants discussed the motivation to find an explanation for an existing family history of speech disorders.

“… [child]‘s father I think also has speech dyspraxia so… I wanted to know if we could trace it back to the paternal side” - Rebecca, uninformative result

While all children enroled into the Genetics of Speech Disorders programme had speech impairment as the primary area of developmental concern, some parents felt that their child had other co-occurring phenotypes which were perceived to be unrelated to the motor speech disorder. These participants reflected that there was probably “more to it”, and were hopeful that genetic testing would provide an explanation for the other clinical symptoms that a speech diagnosis could not.

“We felt that there was something more than just [child]’s speech that was going on, her development seemed to be impacted in many other ways and no other diagnosis sort of seemed to fit” - Molly, diagnostic result

Subtheme: accessing and tailoring clinical care

Participants sought genetic testing to gain a better understanding of their child’s condition and subsequently, their support needs. Many believed that this would inform the most effective therapies for their child.

“… did the intervention that we do match, like were they the right interventions for that. Or moving forward, what would be a better way to manage [child], kind of?” - Kirsty, uninformative result

When discussing this further, participants also wanted to receive information about other comorbidities and their child’s prognosis. In having this information, participants sought to understand there were other clinical considerations in managing their child’s care.

“It was to find out was there anything more medically that [child] might need help with physically, not just in terms of the speech disability, but yeah, more support that he might need or things we need to know about to be aware of and watch out for” - Vivian, diagnostic result

Participants who received uninformative results for their child raised a key motivator for testing that was not reported in participants who received diagnostic results. The former group saw genetic testing as a potential opportunity for their child to obtain a genetic diagnosis, which could improve access to the child’s insurance scheme funding (known as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia).

“So [a genetic diagnosis] would actually give us more, uhm, evidence to receive NDIS funding” - Rosie, uninformative result

Subtheme: providing information for others

Participants also believed that genetic testing could provide useful information both for their families and the wider community affected by motor speech disorders.

In recognising the potential familial implications of a genetic diagnosis, participants sought genetic testing to inform the reproductive risks of their affected child, other children, and other family members.

“I think when I looked at sort of, you know, the big picture of ‘if there is something there’… Is this going to be an impact, not so much on [child], but potentially my grandkids or other - the next sort of generation or somewhere down the track?” – Rosalyn, diagnostic result

Apart from reproductive implications, many participants pursued genetic testing hoping that the results could help other families affected by similar conditions through the contribution to motor speech disorder research, even if unable to provide answers for their own child.

“If anything that could potentially be done so that, you know, however many years down the track… At least, perhaps if there’s a bit more information out there, uhm [other parents]’ journey wouldn’t be quite as lonely” - Joanne, uninformative result

Theme 2: receiving genetic test results was an emotionally complex experience

Participants expressed a range of emotions when receiving their child’s genetic test results. Feelings of relief, uncertainty, disappointment, and shock were consistently reported across both cohorts, albeit for different reasons.

“It is a relief… That means, at least, at this stage her apraxia is not caused by genetic reasons… So hopefully she can grow out of it over time” - Lesley, uninformative result

“It was kind of like this shock that, after all this time, it’s just there” - Neveah, diagnostic result

Notably, many participants experienced emotional duality after result disclosure. For parents who found comfort in finding a genetic answer, there was a remaining sense of uncertainty towards the child’s and family’s future.

“Yeah, that two-sided thing of right, we might have an answer so we can least help [child] in some way. But what does it mean for the other children in our family? What does it mean going forward?” - Lily, diagnostic result

In contrast, those who expressed relief in ruling out potential genetic aetiology still faced uncertainty surrounding the child’s diagnostic odyssey.

“Bittersweet I guess, isn’t it? Like it wasn’t one big obvious bad thing, but oh we still don’t know what it is” - Ashley, uninformative result

Some participants also reflected on the actual utility of obtaining a diagnostic result. For them, receiving a genetic diagnosis does not alter the reality of their child’s condition.

“I mean, the likelihood of getting a genetic test result and then suddenly being able to change or fix or make things easier is probably not realistic” - Nadine, diagnostic result

“If we get a diagnosis, he’s not going to start eating normally the next day, or he’s not going to pronounce his sounds right the next day” - Kirsty, uninformative result

Theme 3: coping with continued uncertainty regardless of testing outcome

Participants across both cohorts reported distinct perceived implications, challenges, support needs and/or coping strategies after receiving their child’s genetic test results.

Subtheme: the dual-sided nature of receiving a genetic label

Participants whose child received genetic diagnostic results shared the utility of having a genetic label for their child’s condition. This label was perceived to be helpful in better understanding their child and advocating for them with family members and healthcare professionals.

“I think it’s helped the doctors to know that if I go in, there’s a reason why and that if she’s not well and not responsive to the doctors then she’s not being naughty as a 21-year-old” - Sophie, diagnostic result

Some participants also appreciated having the knowledge of other comorbidities associated with their child’s genetic diagnosis, which was thought to inform the child’s ongoing and future clinical management.

“And to know too that maybe later on further down the track he may develop epilepsy and it’s something that you know, we’re aware of now that we can keep an eye on” - Hazel, diagnostic result

Besides that, a genetic diagnosis was reported to have helped parents access critical funding for their child.

“Given the difficulty at getting funding at school and NDIS… We’ve got this diagnosis, therefore if he needs support and funding… we will be able to get that as he needs it” - Rosalyn, diagnostic result

Despite the perceived utility in receiving a diagnostic result, participants also discussed the lack of information surrounding their child’s genetic diagnosis. For some, the novelty of this genetic finding resulted in continued uncertainty.

“Nobody else has published anything really about… his syndrome. So, we didn’t get any more information or guidance or anything” - Vivian, diagnostic result

Due to the rarity of these genetic diagnoses, many parents expressed a lack of support groups available. Participants highlighted the importance of having connections to others who are in similar circumstances, so that they can find social support within the community.

“It would be nice to have some sort of contact with other families on the same journey with the same genetic test outcome or test result… Because it’s an unusual one, like you can search the internet and there’s basically nothing about it” - Sophie, diagnostic result

Some participants also discussed their hope for healthcare professionals to provide continuity of care in addressing both their informational and clinical support needs.

“I wish there was some kind of like, update that you received… Something like that ongoing knowledge, rather than googling” - Vivian, diagnostic result

“We have been waiting on the waitlist [of a local genetics service] for just over two years… I guess that’s where we would like to have some further discussions in regards to [child]’s genetic diagnosis and possibly what this means for her future” - Molly, diagnostic result

Subtheme: Finding meaning in uninformative results

Following result disclosure, participants who received uninformative results recognised their child’s continued diagnostic odyssey and acknowledged that finding an answer was not going to be a straightforward process.

“That didn’t answer it and we still got to keep digging… It’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon” - Kirsty, uninformative result

Nevertheless, a negative genetic test result was still perceived to be informative. Despite the lack of explanation for their child’s condition, parents found reassurance in ruling out potential genetic aetiology.

“But also good to know… that there is potentially not a major chromosomal issue or a genetic issue that is linked to his apraxia” - Ruby, uninformative result

In fact, uninformative results also helped participants remain hopeful about their child’s prognosis.

“Yeah, there’s no sort of like surprises hiding around the corner… We’re still making progress, and there’s still opportunities for improvement for him” - Bella, uninformative result

In recognising the limitations around current genetics knowledge and technology, some participants were hopeful that their child’s diagnostic odyssey may come to an end in the future.

“But then it wasn’t the end of the story, it was the end of the chapter… We’re still the two in three, but we might then become the next portion of that third” - Ashley, uninformative result

However, others reported psychological relief in diverting their attention away from the search for answers, and that a speech diagnosis alone was sufficient to provide clarity towards their child’s support needs.

“So, when we got the diagnosis, verbal dyspraxia, I was like okay, okay this I can deal with. We can go to speech therapy, right, I’ve got an action plan” - Rebecca, uninformative results

Additionally, participants expressed unconditional love for their child and noted the importance of focusing on their child’s strengths and progress, regardless of the aetiology of their motor speech disorder.

“As his mum I’m always going to love him no matter what genetic testing says or doesn’t say” - Evelyn, uninformative result

Discussion

Utility of genetic testing for motor speech disorders

In the context of genetic testing, the term “personal utility” refers to client-endorsed values of testing which extend beyond clinical outcomes31. Kohler et al. (2017) developed a theoretical framework comprising four domains to delineate the different facets of personal utility in genetic testing32: (a) the affective domain describes ways in which the pursuit of genetic testing influences one’s emotional state; (b) the cognitive domain represents the gain of knowledge and information post-genetic testing; (c) the behavioural domain involves the practical use of genetic information; and (d) the social domain refers to changes in social outcomes at the familial or societal level. The attitudes and motivators reported in our study can be mapped into all four domains, suggesting that parental perceptions of personal utility around genetic testing for childhood motor speech disorders are multifaceted. This provides an important basis for understanding parental values and delivering client-centred genetic counselling to families affected by motor speech disorders.

The clinical utility of obtaining a genetic diagnosis for childhood motor speech disorders will continue to expand as we develop further understanding around its genetic mechanism of pathogenesis. Recent research has demonstrated the critical roles of CAS-related genes in brain development, and revealed their phenotypic overlap with other neurodevelopmental presentations such as autism, fine motor impairments, and learning difficulties10,12,13. Given our current understanding around the genotype-phenotype correlation of CAS, there is potentially dual clinical utility in identifying its underlying genetic aetiology. Firstly, it has been suggested that a genetic diagnosis could inform the tractability and severity of the child’s speech condition, and subsequently their long-term communication outcomes33. Additionally, children with genetic forms of CAS may benefit from the involvement of a paediatrician, physiotherapist, psychologist and other healthcare professionals in managing co-occurring phenotypes and optimising the child’s outcome34. In order to facilitate well-informed discussions around the clinical utility of genetic testing for childhood motor speech disorders, healthcare professionals providing genetic counselling to these families should be equipped with up-to-date knowledge around the genetic basis of the condition, as well as its therapeutic and prognostic implications.

Managing post-test emotional complexity

Our participants experienced a range of complex emotions in receiving their child’s genetic test results, many of which were dual-sided. This concept of emotional duality post-result disclosure has been reported in other neurodevelopmental literature, in that parents commonly experience emotional conflict between feelings of relief and a sense of grief or disappointment, regardless of testing outcome35,36. Similarly, our results showed that while parents perceived an overall emotional benefit to receiving a genetic diagnosis, they also experienced shock, uncertainty, and grief for their child’s previously envisioned future. Conversely, parents who received uninformative results found reassurance in ruling out known severe genetic conditions, although there remained a sense of uncertainty surrounding the child’s ongoing diagnostic odyssey.

These emotional responses may be driven by parental expectations around testing outcomes. Similar correlations have been observed in other studies, whereby the profound hope or unpreparedness for a positive genetic finding often leads to feelings of disappointment or helplessness upon receiving diagnostic or uninformative genetic test results, respectively37,38. Considering the novelty of genetic testing for childhood motor speech disorders, most children without co-occurring phenotypes are unlikely to have undergone prior genetic investigations. This may induce a unique sense of hope towards a particular genetic testing outcome, which should be managed with a fine balance between upholding parental optimism and providing realistic expectations around the diagnostic yield of testing. This highlights the critical role that genetic counsellors can play in providing adequate psychosocial support to these families throughout their genetic testing journey39. Emerging research has demonstrated speech pathologists’ desire to work collaboratively with genetic counsellors39. This may involve genetic counsellors supporting speech pathologists to provide pre-test information and anticipatory guidance to families, and reciprocal education between both professions around motor speech disorders and genetic testing concepts or pathways39.

Providing support post-result disclosure

Despite receiving a genetic diagnosis for their child’s motor speech disorder, our results indicate that the rarity of many of these diagnoses lead to uncertainty about non-speech related phenotype and prognosis. Rosell et al. (2016) considered this concept in the context of paediatric undiagnosed conditions, identifying that this uncertainty creates frustration for parents40. Mirroring our findings, other parents also reported a lack of information surrounding their child’s genetic diagnosis and discussed the need for more clinical guidance and peer support post-testing41,42. To address this, our participants highlighted the perceived value of follow-up and continuity of care provided by healthcare professionals, particularly when new information relevant to the child’s clinical care becomes available. Besides that, there was also a strong desire to connect with other families who have similar lived experiences. This is consistent with previous neurodevelopmental literature which described the utility of post-test referral to support groups in addressing parental emotional and practical support needs after receiving their child’s genetic diagnosis25,40.

For participants receiving uninformative genetic test results, many felt that the information gained was nonetheless inherently valuable. It also provided temporary closure for parents as they redirected their focus towards the child’s unique strengths and qualities. Nevertheless, some participants remained hopeful for potential future findings. While similar observations have been reported in literature36,40, it is noteworthy that parents in some studies expressed satisfaction with their child’s status quo and felt comfortable in ending their search for a genetic explanation43,44. Therefore, understanding the meaning attached to both uninformative genetic test results and the possibility of a future genetic diagnosis is imperative in facilitating parental adaptation post-result disclosure.

Interdisciplinary practice between speech pathologists and genetic counsellors involving reciprocal education, guidance, and collaboration may be effective in helping families navigate the post-result disclosure period39. Working within their respective scopes of practice, these healthcare professionals may be able to leverage their unique skill sets to provide support across a range of areas, including motor speech disorder treatment and prognosis, psychosocial wellbeing, and parental adaptation.

Limitations

Our participants’ views and experiences may not be reflective of the broader genetic services offered outside the context of the Genetics of Speech Disorders programme. Additionally, some parents enroled their child in the Genetics of Speech Disorders programme to establish or confirm their motor speech disorder diagnosis. This may result in different parental perspectives compared to situations wherein genetic testing is performed after the child’s speech diagnosis has been established. We also acknowledge that there was variability in the time interviews were conducted post-results disclosure, and that this variable may have influenced parental perspectives and/or experiences and could be examined further in future studies. The generalisability of our results may also be limited by sampling bias, as parents who participated may have held stronger views, either in favour of or against genetic testing. Lastly, our participants were demographically homogeneous, consisting exclusively of English-speaking mothers. Parents from other socially and linguistically diverse backgrounds may have different perspectives.

Considerations for future research

In the present Australian context, clinical genomic testing for children with motor speech disorders cannot be accessed via a government-funded clinical genetics service or medical practitioner. At present, there is one research-funded pathway, specifically our Genetics of Speech Disorders Clinic; however families can also obtain privately-funded sequencing. As genomic testing for childhood speech disorders becomes increasingly available, evidence-based implementation frameworks are needed to develop multidisciplinary delivery models of genetics healthcare for children and families affected by the condition. Together with the present study, identification of barriers and enablers of integrating genomics into the field of speech pathology39 and cost-effectiveness studies45 can be built upon to support the implementation of genomic testing for childhood speech disorders into clinical speech pathology practice. Additional research is also needed to understand and delineate the roles of different healthcare providers in maintaining continuity of care and supporting families in coping with the continued uncertainty post-genetic testing.

Conclusion

Our findings provided valuable insights to inform the provision of genetic counselling to families affected by childhood motor speech disorders. Specifically, our results can help frame pre-test discussions to understand parental values, motivators, and concerns towards genetic testing. In the context of post-test counselling, healthcare professionals should be prepared to manage complex parental emotions after returning genetic test results. Our results also illustrated the ongoing support needs of parents who receive a genetic diagnosis, and some emotional and practical coping strategies to help families adapt towards their child’s continued diagnostic odyssey. Given the pleiotropic nature of genes related to childhood motor speech disorders, a multidisciplinary approach is needed to deliver effective genetics healthcare. In particular, close collaboration between clinical geneticists, genetic counsellors, and non-genetics healthcare professionals such as speech pathologists and developmental paediatricians is paramount in providing adequate pre-test and post-test support to these families.

Data availability

Data analysed in the present study can be found within the published article, and in Supplementary File 2. Further data sets associated with this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Reilly S, McKean C, Morgan A, Wake M. Identifying and managing common childhood language and speech impairments. BMJ. 2015;350:h2318. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2318.

Morgan A, Ttofari EecanK, Pezic A, Brommeyer K, Mei C, Eadie P, et al. Who to refer for speech therapy at 4 years of age versus who to “watch and wait”? J Pediatr. 2017;185:200–4.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.02.059.

Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J, Mabie HL. Estimates of the prevalence of motor speech disorders in children with idiopathic speech delay. Clin Linguist Phon. 2019;33:679–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2019.1595731.

Cassar C, McCabe P, Cumming S. I still have issues with pronunciation of words”: a mixed methods investigation of the psychosocial and speech effects of childhood apraxia of speech in adults. Int J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2023;25:193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2021.2018496.

Liégeois FJ, Mei C, Pigdon L, Lee KJ, Stojanowski B, Mackay M, et al. Speech and language impairments after childhood ischemic stroke: Does hemisphere matter? Pediatr Neurol. 2019;92:55–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.11.006.

Liégeois FJ, Morgan AT. Neural bases of childhood speech disorders: Lateralization and plasticity for speech functions during development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:439–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.07.011.

Morgan AT, Masterton R, Pigdon L, Connelly A, Liégeois FJ. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of chronic dysarthric speech after childhood brain injury: Reliance on a left-hemisphere compensatory network. Brain. 2013;136:646–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws355.

den Hoed J, Fisher SE. Genetic pathways involved in human speech disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2020;65:103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2020.05.012.

Deriziotis P, Fisher SE. Speech and language: translating the genome. Trends Genet. 2017;33:642–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2017.07.002.

Morgan AT, Amor DJ, St John MD, Scheffer IE, Hildebrand MS. Genetic architecture of childhood speech disorder: a review. Mol Psychiatry. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02409-8.

Eising E, Carrion-Castillo A, Vino A, Strand EA, Jakielski KJ, Scerri TS, et al. A set of regulatory genes co-expressed in embryonic human brain is implicated in disrupted speech development. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:1065–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0020-x.

Hildebrand MS, Jackson VE, Scerri TS, Van Reyk O, Coleman M, Braden RO, et al. Severe childhood speech disorder: Gene discovery highlights transcriptional dysregulation. Neurology. 2020;94:e2148–67. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009441.

Kaspi A, Hildebrand MS, Jackson VE, Braden R, van Reyk O, Howell T, et al. Genetic aetiologies for childhood speech disorder: Novel pathways co-expressed during brain development. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:1647–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01764-8.

Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, Berkman BE, Bombard Y, Holm IA, et al. Points to consider: Ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:6–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.022.

Morgan A, Fisher SE, Scheffer I, Hildebrand M. FOXP2-related speech and language disorder. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, et al., eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2023.

Vears DF, Ayres S, Boyle J, Mansour J, Newson AJ, et al. Human Genetics Society of Australasia Position Statement: Predictive and presymptomatic genetic testing in adults and children. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2020;23:184–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2020.51.

Crellin E, Martyn M, McClaren B, Gaff C. What matters to parents? A scoping review of parents’ service experiences and needs regarding genetic testing for rare diseases. Eur J Hum Genet. 2023;31:869–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-023-01376-y.

Alam A, Parfyonov M, Huang CY, Gill I, Connolly MB, Illes J. Targeted whole exome sequencing in children with early-onset epilepsy: Parent experiences. J Child Neurol. 2022;37:840–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738221113901.

Dikow N, Moog U, Karch S, Sander A, Kilian S, Blank R, et al. What do parents expect from a genetic diagnosis of their child with intellectual disability? J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;32:1129–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12602.

Zhang Z, Kramer J, Wang H, Chen W, Huang T, Chen Y, et al. Attitudes toward pursuing genetic testing among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in Taiwan: A qualitative investigation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19:118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010118.

Ayhan AB, Beyazit U, Topuz Ş, Tunay ÇZ, Abbas MN, Yilmaz S. Autism spectrum disorder and genetic testing: Parents’ attitudes - data from a Turkish sample. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51:3331–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04798-5.

Tremblay I, Grondin S, Laberge A, Cousineau D, Carmant L, Rowan A, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic misconception: Parental expectations and perspectives regarding genetic testing for developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:363–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3768-6.

Groisman IJ, Hurlimann T, Godard B. Parents of a child with epilepsy: Views and expectations on receiving genetic results from whole genome sequencing. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;90:178–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.11.020.

Jeffrey JS, Leathem J, King C, Mefford HC, Ross K, Sadleir LG. Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy: Personal utility of a genetic diagnosis for families. Epilepsia Open. 2021;6:149–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12458.

Nevin SM, Wakefield CE, Barlow-Stewart K, McGill BC, Bye A, Palmer EE, et al. Psychosocial impact of genetic testing on parents of children with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14971.

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2015;42:533–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.

Zoom Video Communications Inc. Zoom cloud meetings [Computer program]. 2022. https://zoom.us/.

QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo [Computer program]. March, 2020. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

Bernard HR. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage Publications; 2013.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Kohler JN, Turbitt E, Lewis KL, Wilfond BS, Jamal L, Peay HL, et al. Defining personal utility in genomics: a Delphi study. Clin Genet. 2017;92:290–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12998.

Kohler JN, Turbitt E, Biesecker BB. Personal utility in genomic testing: A systematic literature review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:662–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2017.10.

Morgan A. Speech-language pathology insights into genetics and neuroscience: Beyond surface behaviour. Int J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2013;15:245–54. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.777786.

Solot CB, Sell D, Mayne A, Baylis AL, Persson C, Jackson O, et al. Speech-language disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Best practices for diagnosis and management. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2019;28:984–99. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJSLP-16-0147.

Lee W, Luca S, Costain G, Snell M, Marano M, Curtis M, et al. Genome sequencing among children with medical complexity: What constitutes value from parents’ perspective? J Genet Couns. 2022;31:523–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1522.

Martinussen J, Chalk M, Elliott J, Gallacher L. Receiving genomic sequencing results through the Victorian Undiagnosed Disease Program: Exploring parental experiences. J Pers Med. 2022;12:1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12081250.

Bauskis A, Strange C, Molster C, Fisher C. The diagnostic odyssey: Insights from parents of children living with an undiagnosed condition. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17:233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02358-x.

Donohue KE, Dolan SM, Watnick D, Gallagher KM, Odgis JA, Suckiel SA, et al. Hope versus reality: Parent expectations of genomic testing. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104:2073–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.01.030.

Lauretta ML, Jarmolowicz A, Amor DJ, Best S, Morgan AT. An investigation of barriers and enablers for genetics in speech-language pathology explored through a case study of childhood apraxia of speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_JSLHR-22-00714.

Rosell AM, Pena LDM, Schoch K, Spillmann R, Sullivan J, Hooper SR, et al. Not the end of the odyssey: Parental perceptions of whole exome sequencing (WES) in pediatric undiagnosed disorders. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1019–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-016-9933-1.

Poduri A, Sheidley BR, Shostak S, Ottman R. Genetic testing in the epilepsies - developments and dilemmas. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:293–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.60.

Reiff M, Giarelli E, Bernhardt BA, Easley E, Spinner NB, Sankar PL, et al. Parents’ perceptions of the usefulness of chromosomal microarray analysis for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:3262–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2489-3.

Liang NSY, Adam S, Elliott AM, Siemans A, du Souich C, Causes Study, et al. After genomic testing results: Parents’ long-term views. J Genet Counsel. 2022;31:82–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1454.

Watnick D, Odgis JA, Suckiel SA, Gallagher KM, Teitelman N, Donohue KE, et al. Is that something that should concern me?”: A qualitative exploration of parent understanding of their child’s genomic test results. Hum Genet Genomics Adv. 2021;2:100027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2021.100027.

Meng Y, Best S, Amor DJ, Braden R, Morgan AT, Goranitis I. The value of genomic testing in severe childhood speech disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2024;32:440–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01534-w.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the parents who generously gave their time and insights to participate in this research study.

Funding

This research was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Speech and Language Neurobiology Grant 1116976 and NHMRC Project Grant APP1127144, awarded to Angela T. Morgan. NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship Grant 1105008 and Investigator Grant 1195955 were awarded to Angela T. Morgan. This study was completed in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Genetic Counselling programme, the University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. This work was also supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ATM, DA, and AJ conceived, designed, and supervised the study. CA and YQL performed data acquisition and analysis, with supervision from AJ. CA, YQL, and ML drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the review of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia (reference number: 37353).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Atkinson, C., Lee, Y.Q., Lauretta, M.L. et al. Parental attitudes and experiences in pursuing genetic testing for their child’s motor speech disorder. Eur J Hum Genet 33, 930–936 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01755-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-024-01755-z

This article is cited by

-

Summer reading 2025 in EJHG

European Journal of Human Genetics (2025)