Abstract

Epidemiologic findings indicate that unfavorable cardiovascular (CV) risk profiles, such as elevated systolic blood pressure (SBP), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and overweight, decelerate with aging. Few studies, however, have evaluated the association between the CV risk profile and frailty. We performed a cross-sectional analysis using the baseline data of a prospective cohort study. A total of 599 subjects (age, 78 [range: 70–83] years; men, 50%) were analyzed in an outpatient setting. Frailty was diagnosed in 37% of the patients according to the Kihon Checklist score. An unfavorable CV risk profile was associated with a lower risk of frailty. The adjusted odds ratios (ORs; 95% confidence interval [CI]) of each CV risk factor for frailty were as follows: SBP (each 10 mmHg increase) 0.83 (0.72–0.95), LDL-C (each 10 mg/dl increase) 0.96 (0.86–1.05), and body mass index (each 1 kg/m2 increase) 1.03 (0.97–1.10). Moreover, the total number of CV risk factors within the optimal range was significantly associated with the risk of frailty with the following ORs (95% CI): 1, 2.30 (0.75–8.69); 2, 3.22 (1.07–11.97); and 3, 4.79 (1.56–18.05) compared with patients having no risk factors within optimal levels (p for trend 0.008). Abnormal homeostasis might lead to lower levels of CV risk factors, which together result in “reverse metabolic syndrome.” Our findings indicate that a favorable CV risk profile is associated with frailty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frailty is defined as a state of increased vulnerability resulting from age-associated declines in reserve and the functions of multiple physiological systems, such that the ability to cope with every day or acute stressors is compromised [1]. The morbidity of frailty of Japanese community-dwelling elderly aged 65 years or older is 10–30% [2, 3], and the prevalence increases with increasing age [4, 5]. Moreover, frailty independently predicts incident falls, worsening mobility or activities of daily living, disability, hospitalization, and death [4, 5]. In Japan, a super aging society, more than one-third of the population is considered elderly, and thus, the increase in frailty is not only a personal issue but also a public issue. In community-dwelling elderly people, cardiovascular (CV) disease is associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 3–4 for prevalent frailty and 1.5 for incident frailty [6]. Moreover, patients with severe coronary artery disease or heart failure are likely to have comorbid frailty, which is associated with a high risk of all-cause mortality [6].

Management of the CV risk factors in these patients is crucial to improve prognosis. Our understanding of the association between frailty and CV risk factors or risk clustering, however, is limited. Population-based studies indicate that frailty is associated with an increased risk of CV risk factors independent of established CV disease [7,8,9,10]. Among hospitalized elderly people, the association between frailty and CV risk factors is equivalent [11]. A community-based study of subjects aged 90 years or over demonstrated that frailty, but not metabolic syndrome, increases mortality risk [12]. In very old patients, on the other hand, low body mass index (BMI), low blood pressure (BP), and low total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol strongly predict total mortality [13]. There are currently no guidelines for the management of CV risk factors in this spectrum of subjects, and no optimal levels have been established. Given this background, we evaluated the CV risk profile of patients with frailty in an outpatient setting.

Methods

Study patients

The Nambu Cohort Study is a prospective cohort study of elderly patients in an outpatient setting in the southern area of Okinawa, Japan, that began in 2017. The aim of the study is to collect data regarding the prolongation of a healthy life expectancy to evaluate the clinical significance of frailty. Patients 65 years of age or older treated for CV disease, such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease, and heart failure, were registered at each institute. Patients who could complete the interview by the medical assistant to provide information regarding frailty were continuously registered. Among them, patients <65 years old and those with Kihon Checklist score of 5 (the worst) in the activities of daily living and physical function section were excluded. Finally, a total of 599 patients were analyzed (Fig. 1). We performed a cross-sectional analysis to evaluate the CV risk profile and comorbidities in these patients and analyzed the effect of frailty using baseline data from the Nambu Cohort Study.

Data collection

Blood pressure and resting heart rate were recorded using an automatic blood pressure monitor (HBP-9020, Omron Corp. Kyoto, Japan) after having the subject sit for 10 min. Body weight and height were measured to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively, with the subjects wearing light indoor clothing and no shoes. Body mass index was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). All blood samples were obtained from the antecubital vein after an overnight fast. Fasting plasma glucose was measured using the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. Serum creatinine, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were measured by enzymatic methods. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol was measured by a direct method. The hemoglobin A1c level was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Leukocyte counts, hematocrit, hemoglobin level, and platelet count were quantified using an automated blood cell counter. Grip strength was measured with a Smedley-type (mechanical) handgrip dynamometer (TTM, Tokyo, Japan).

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or antihypertensive drug use. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥ 126 mg/dl (7 mmol/L), hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%, or taking an antidiabetic drug. Dyslipidemia was defined as LDL-C ≥ 140 mg/dl (5.69 mmol/L) if patients did not have CAD and ≥100 mg/dl if patients did have CAD or used statins. CAD was defined as angiographically documented significant coronary stenosis, history of myocardial infarction, history of percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass graft. Stroke was defined as cerebral thromboembolism and cerebral hemorrhage documented by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Chronic kidney disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73m2. Chronic heart failure was defined as a history of congestive heart failure or brain natriuretic peptide levels of 100 pg/ml or more [14]. Peripheral artery disease was defined as an ankle brachial index < 0.9 [15] or patients undergoing percutaneous transarterial angioplasty. Cardiovascular risk factors included hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Optimal CV risk control levels were defined as BP < 140/90 mmHg, BMI < 25 kg/m2, and LDL-C < 140 if the patients did not have CAD and <100 mg/dl if the patients had CAD or used statins.

Frailty was diagnosed using the Kihon Checklist. The Kihon Checklist is a simple self-reporting yes/no survey comprising 25 questions regarding instrumental (3 questions) and social (4 questions) activities of daily living, physical functions (5 questions), nutritional status (2 questions), oral function (3 questions), cognitive function (3 questions), and depressive mood (5 questions). This comprehensive questionnaire assesses the physical, psychological, functional, and social status of nondisabled older adults in multiple domains. The usefulness of the Kihon Checklist as an index of frailty was verified by Satake et al. [16]. A Kihon Checklist score of 0–3 was considered to indicate non-frailty, 4–7 pre-frailty, and ≥8 was considered to indicate frailty [16]. Well-trained medical assistants asked the patients about the content of the Kihon Checklist before the medical examination and recorded the patients’ responses.

Statistical analysis and ethics

The clinical characteristics of the study population stratified by frailty were compared using a one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables according to the normality of the distributions and chi-square test for categorical variables. The distribution normality was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges), and categorical data are presented as frequencies. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for frailty were calculated after adjusting for confounding variables using multiple logistic regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Social Medical Corporation Yuaikai, Okinawa, Japan.

Results

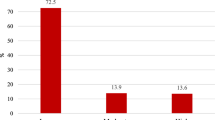

A total of 599 patients with a median age of 78 (70–83) years, 50% of whom were men, were evaluated. A total of 178 patients (30%) were considered non-frail, 197 patients (33%) were diagnosed as pre-frail, and 224 patients (37%) were diagnosed as frail. The baseline characteristics of the patients stratified by frailty status are shown in Table 1. Patients with frailty were significantly older, had a lower level of handgrip strength, and were more likely to have CV disease. The frequency of patients with multiple CV risk factors tended to decrease in frail patients, but the effect was not statistically significant. The CV risk levels of these patients according to frailty level, however, were in the opposite direction. Frail patients were likely to have lower BP, BMI, and serum lipid levels. Plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels were not significantly different regardless of frailty. Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of CV risk factors on frailty. Frailty was significantly associated with SBP, marginally associated with LDL-C, and not associated with BMI. The odds ratio (OR; 95% confidence interval [CI]) of a unit increases in each risk factor was as follows: SBP (each 10 mmHg increase) 0.83 (0.72–0.95, p = 0.008); LDL-C (each 10 mg/dl increase) 0.96 (0.86–1.05, p = 0.301); and BMI (each 1 kg/m2 increase) 1.03 (0.97–1.10, p = 0.306) (Fig. 2). Finally, we evaluated the association between the number of CV risk factors within the optimal level according to the clinical guidelines and frailty (Table 2). The ORs (95% CIs) for frailty of patients with one, two, and three CV risk factors within the optimal level were 2.30 (0.75–8.69, p = 0.153), 3.22 (1.07–11.79, p = 0.038), and 4.79 (1.56–18.05, p = 0.005), respectively, compared with patients without a CV risk factor within the optimal level after adjusting for confounding factors. We also performed a sensitivity analysis using zero and one CV risk factor within the optimal level (n = 182) as the reference group and showed similar results (adjusted OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.95–2.51, p = 0.077 for two and OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.36–3.92, p = 0.002 for three CV risk factors within the optimal level).

Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for frailty of 599 patients in the Nambu Cohort Study. Data were adjusted for age, sex, handgrip, blood pressure, and lipid-lowering medication, such as calcium channel blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, and statin use, and comorbidity, such as coronary artery disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and atrial fibrillation

Discussion

The results of the present analysis demonstrated that frailty is significantly associated with lower BP and a tendency toward a lower LDL-C but not with BMI levels. More interestingly, a higher number of CV risk factors within the optimal level accelerates the risk of frailty. To the best of our knowledge, these findings are the first to demonstrate an association between CV risk level and the accumulation of CV risk factors with frailty.

Cardiovascular risk factors in frailty

The evidence demonstrating an association between CV risk factors and frailty is limited. A population-based study demonstrated an association between frailty and CV risk factors independent of established CV disease [7], especially diabetes [8]. Moreover, the prevalence of frailty was higher in those with prior CV disease, and combined CV risk factors were linearly and positively associated with frailty [9]. An association between CV risk and frailty was also found in hospital patients [11]. Subjects with frailty are at risk for all-cause death or a CV event [17, 18]. The difference between the previous results and ours might derive from the characteristics of the cohort. Our cohort was significantly older, had a lower BMI, and, more importantly, had more CV comorbidities, especially a higher prevalence of stroke (Table 1). The higher prevalence of stroke in our cohort might be the main reason for the higher prevalence of frailty compared with the other cohorts. These characteristics of our subjects accelerate biological aging and lead to the catabolic syndrome that is often observed in very old subjects [19].

Lower SBP levels are associated with poor prognosis in community-dwelling elderly persons [20, 21] and persons with frailty [22,23,24]. Both cholesterol and BMI levels are also inversely associated with prognosis in elderly subjects [25, 26], and a 1 mmol/L (38.6 mg/dl) increase in total cholesterol is associated with an 18% reduction in mortality [26]. Elderly subjects with a BMI > 30 had the lowest mortality during a 5-year follow-up [27]. The relative risk of death associated with excess adiposity is lower for older adults than for younger adults [28]. Not only the baseline levels of CV risk factors but also a serial decline in these factors is crucial for patient prognosis. The trajectory of BP, cholesterol, and BMI in elderly subjects gradually declines by the time of death [29,30,31]. These time-dependent changes in CV risk factor levels might be associated with a physical status change from robust to frail, to end of life, and finally death and indicate that homeostasis is disrupted in frail subjects, continuing to the end of life [32]. In elderly patients, these CV risk factors may still be hazardous, but the direction is totally the opposite, a phenomenon known as “reverse epidemiology” or “reverse metabolic syndrome” [19, 33].

Mechanisms of reverse metabolic syndrome

Aging, usually referring to chronological age, is a powerful and independent risk factor for prognosis. Frailty is a state, in which homeostasis against stress is impaired and is considered to accelerate biological aging [32]. Frailty might bridge the gap between chronological aging and biological aging. A crucial threshold of age-related cumulative decline, beyond which frailty becomes evident, exists in many physiological systems. Among several possible mechanisms that contribute to the progression of frailty, age-related low-grade chronic inflammation may contribute to muscle wasting in sarcopenia through the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines [34]. Subjects with frailty may have an imbalance in muscle homeostasis leading to accelerated muscle breakdown. Inflammatory cytokines activate muscle breakdown to generate amino acids for energy and cleave antigenic peptides [34], referred to as catabolic syndrome [19]. This circumstance also leads to hemodynamic instability, resulting in decreased BP, as found in our study. BMI may not reflect muscle loss caused by frailty because the muscle mass loss observed in frail elderly individuals could be masked by age-related changes in body composition [35]. In fact, our results indicated no association between BMI and frailty, which supports this phenomenon.

A strength of the present study is that it confirms the association between the favorable CV risk profile and frailty. Frailty is a systemic phenomenon in elderly patients with disrupted homeostasis. Physicians should pay more attention to the levels of CV risk factors—not only their increase but also their decline. An unexpected decline in the risk factor level might also indicate frailty. At the present time, the optimal BP/lipid level for subjects with frailty is not clear. In elderly patients, frailty may be a useful indicator for screening subjects for whom “lower is better” and subjects for whom excessive control is a risk factor.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, patients who required assistance to walk and nursing home residents were part of the population included in the original database used for this study. To classify all the patients as ambulatory, we excluded those patients with a Kihon Checklist score of 5 (the worst) in the physical function section. Simply excluding those with a score of 5, however, might not provide an accurate representation of ambulatory patients. Second, patients in this study were recruited from a hospital or clinic, and most had multiple comorbidities. For these reasons, the patients in this study were quite different from the general population. Third, the patients were residents of a relatively limited region—the southern part of Okinawa, Japan. Although the results of the present analysis are consistent with previous findings, caution should be taken in generalizing the results. Lastly, this was a cross-sectional observational study with the inherent limitations and biases of such studies. It is unclear whether the optimal risk level leads to undesired outcomes. A prospective study to evaluate these issues is warranted.

Conclusion

A favorable CV risk profile was associated with frailty in an outpatient setting.

References

Xue Q-L. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009

Satake S, Shimokata H, Senda K, Kondo I, Toba K. Validity of total Kihon Checklist Score for predicting the incidence of 3-year dependency and mortality in a community-dwelling older population. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:552.e1–e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.03.013

Yamada Y, Nanri H, Watanabe Y, Yoshida T, Yokoyama K, Itoi A, et al. Prevalence of frailty assessed by fried and Kihon Checklist Indexes in a prospective cohort study: design and demographics of the Kyoto-Kameoka Longitudinal Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:733.e7–e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.022

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

Gale CR, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Prevalence of frailty and disability: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing. 2015;44:162–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu148

Afilalo J, Karunananthan S, Eisenberg MJ, Alexander KP, Bergman H. Role of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1616–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.375

Ramsay SE, Arianayagam DS, Whincup PH, Lennon LT, Cryer J, Papacosta AO, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile and frailty in a population-based study of older British men. Heart. 2015;101:616–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306472

Ricci NA, Pessoa GS, Ferriolli E, Dias RC, Perracini MR. Frailty and cardiovascular risk in community-dwelling elderly: a population-based study. Clin Intertv Aging. 2014;9:1677–85. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S68642

Wong TY, Massa MS, O’Halloran AM, Kenny RA, Clarke R. Cardiovascular risk factors and frailty in a cross-sectional study of older people: implications for prevention. Age Ageing. 2018;47:714–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy080

Garre-Olmo J, Calvó-Perxas L, López-Pousa S, de Gracia Blanco M, Vilalta-Franch J. Prevalence of frailty phenotypes and risk of mortality in a community-dwelling elderly cohort. Age Ageing. 2013;42:46–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afs047

Tavares DM, dos S, Colamego CG, Pegorari MS, Ferreira PC, dos S, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with frailty syndrome among hospitalized elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2016;134:393–9. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2016.0028010616

Hao Q, Song X, Yang M, Dong B, Rockwood K. Understanding risk in the oldest old: frailty and the metabolic syndrome in a chinese community sample aged 90+ years. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;20:82–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-015-0553-5

Testa G, Cacciatore F, Galizia G, Della-Morte D, Mazzella F, Russo S, et al. Charlson Comorbidity Index does not predict long-term mortality in elderly subjects with chronic heart failure. Age Ageing. 2009;38:734–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp165

Colucci WS, Chen HH. Natriuretic peptide measurement in heart failure - UpToDate. 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/natriuretic-peptide-measurement-in-heart-failure.

Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss LK. et al. ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease (updating the 2005 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2020–45.

Satake S, Senda K, Hong Y-J, Miura H, Endo H, Sakurai T, et al. Validity of the Kihon Checklist for assessing frailty status. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:709–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12543

Sergi G, Veronese N, Fontana L, De Rui M, Bolzetta F, Zambon S, et al. Pre-frailty and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly men and women: the Pro.V.A. study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:976–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.040

Vaes B, Depoortere D, Van Pottelbergh G, Matheï C, Neto J, Degryse J. Association between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and mortality in the oldest old: untangling the role of frailty. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0626-x

Curcio F, Sasso G, Liguori I, Ferro G, Russo G, Cellurale M, et al. The reverse metabolic syndrome in the elderly: Is it a “catabolic” syndrome? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:547–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-017-0815-7

Taylor JO, Cornoni-Huntley J, Curb JD, Manton KG, Ostfeld AM, Scherr P, et al. Blood pressure and mortality risk in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:489–501.

Boshuizen HC, Izaks GJ, van Buuren S, Ligthart GJ. Blood pressure and mortality in elderly people aged 85 and older: community based study. BMJ. 1998;316:1780–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.316.7147.1780

Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN, Covinsky KE. Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: the impact of frailty. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1162–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2555

Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, Fay R, Rolland Y, Valbusa F, et al. Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: the PARTAGE study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:989–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8012

Rådholm K, Festin K, Falk M, Midlöv P, Mölstad S, Östgren CJ. Blood pressure and all-cause mortality: a prospective study of nursing home residents. Age Ageing. 2016;45:826–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw122

Schatz IJ, Masaki K, Yano K, Chen R, Rodriguez BL, Curb JD. Cholesterol and all-cause mortality in elderly people from the Honolulu Heart Program: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358:351–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05553-2

Tuikkala P, Hartikainen S, Korhonen MJ, Lavikainen P, Kettunen R, Sulkava R, et al. Serum total cholesterol levels and all-cause mortality in a home-dwelling elderly population: a six-year follow-up. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28:121–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2010.487371

Mattila K, Haavisto M, Rajala S. Body mass index and mortality in the elderly. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292:867–8.

Stevens J, Cai J, Pamuk ER, Williamson DF, Thun MJ, Wood JL. The effect of age on the association between body-mass index and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199801013380101

Ding M, Hu Y, Schwartz J, Koh W-P, Yuan J-M, Sesso HD, et al. Delineation of body mass index trajectory predicting lowest risk of mortality in U.S. men using generalized additive mixed model. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:698–703.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.08.006

Charlton J, Ravindrarajah R, Hamada S, Jackson SH, Gulliford MC. Trajectory of total cholesterol in the last years of life over age 80 years: cohort study of 99,758 participants. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:1083–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx184

Ravindrarajah R, Hazra NC, Hamada S, Charlton J, Jackson SHD, Dregan A, et al. Systolic blood pressure trajectory, frailty, and all-cause mortality >80 years of age: cohort study using electronic health records. Circulation. 2017;135:2357–68. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026687

Ferrucci L, Cavazzini C, Corsi A, Bartali B, Russo CR, Lauretani F, et al. Biomarkers of frailty in older persons. J Endocrinol Investig. 2002;25:10–5.

Kalantar-Zadeh K, Horwich TB, Oreopoulos A, Kovesdy CP, Younessi H, Anker SD, et al. Risk factor paradox in wasting diseases. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:433–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e3281a30594

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

Jackson AS, Janssen I, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Longitudinal changes in body composition associated with healthy ageing: men, aged 20-96 years. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1085–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511003886

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms. Makiko. Chinen, Ms. Masae Toma, Ms. Mitsue Nakajo, Ms. Asuka Kina, Ms. Minako Kikuyama, Ms. Megumi Ishiki, Ms. Mizuki Ohkata, Ms. Miwa Sunagawa, Ms. Minako Yamaniha, Ms. Masami Fukuyama, Ms. Minatsu Yamashiro, Ms. Megumi Kawabata, Ms. Sawako Sakugawa, Ms. Yuka Shimazaki, Ms. Kaori Unten, Ms. Mitsue Kuwae, Ms. Shoko Nagamine, Ms. Aya Henzan, Ms. Sayuri Matsumura, Ms. Yuko Kohno, Ms. Yoko Karakasa, and Ms. Rie Kubota for their dedicated work and Mr. Makoto Ohmine for retrieving the data. The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Mr. Kazuhide Nizato and Ms. Kuniko Inoue for their dedicated assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TI performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. HA also performed the statistical analysis and participated in drafting the manuscript. TS, MT, and OA participated in the study design. AM and KO participated in study coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuoka, M., Inoue, T., Shinjo, T. et al. Cardiovascular risk profile and frailty in Japanese outpatients: the Nambu Cohort Study. Hypertens Res 43, 817–823 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0427-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0427-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Body mass index and sarcopenia and mortality risk among older hypertensive outpatients; the Nambu Cohort Study

Hypertension Research (2025)

-

Current topics of frailty in association with hypertension and other medical conditions

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Frailty in Stroke Patients: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review

The Journal of nutrition, health and aging (2023)

-

Risk factors for frailty in elderly Japanese people who received Ningen Dock: a cross-sectional study

The Egyptian Journal of Internal Medicine (2022)

-

Comparative accuracies of automated and manual office blood pressure measurements in a Chinese population

Hypertension Research (2022)