Abstract

Ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring (ABPM) may cause sleep disturbances. Some home BP monitoring (HBPM) devices obtain a limited number of BP readings during sleep and may be preferred to ABPM. It is unclear how closely a few BP readings approximate a full night of ABPM. We used data from the Jackson Heart (N = 621) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (N = 458) studies to evaluate 74 sampling approaches to estimate BP during sleep. We sampled two to four BP measurements at specific times from a full night of ABPM and computed chance-corrected agreement (i.e., kappa) of nocturnal hypertension (i.e., mean asleep systolic BP ≥ 120 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 70 mmHg) defined using the full night of ABPM and subsets of BP readings. Measuring BP at 2, 3, and 4 h after falling asleep, an approach applied by some HBPM devices obtained a kappa of 0.81 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.78, 0.85). The highest kappa was obtained by measuring BP at 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep: 0.84 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.87). In conclusion, measuring BP three or four times during sleep may have high agreement with nocturnal hypertension status based on a full night of ABPM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Higher blood pressure (BP) levels during sleep have been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and target organ damage, independent of BP measured in a clinical setting [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) typically measures BP every 15–30 min throughout the day and night [7] and is recognized as the gold standard for measuring nocturnal BP [8]. Although most people find ABPM acceptable, it may cause sleep disturbances for some individuals [9,10,11,12]. Home BP monitoring (HBPM) is another approach for measuring BP outside of the office setting, and some HBPM devices can be programmed to measure BP at specific times, including when someone is asleep. HBPM devices are available that measure BP at 2, 3, and 4 a.m. and 2, 3, and 4 h after falling asleep [13,14,15,16,17].

Obtaining fewer BP readings during sleep with an HBPM device instead of BP from a full night’s sleep on an ABPM device may reduce discomfort and disrupted sleep. However, the fewer BP measurements obtained using HBPM instead of ABPM may result in a loss of information and a weaker association with outcomes [18]. Others have previously studied the validity of using a fixed number of BP measurements sampled randomly during wakefulness or sleep to determine how many measurements were needed for the reliable estimation of mean BP during sleep in the research setting [19, 20]. Few studies have estimated the number and timing of BP measurements required to obtain an estimate of mean BP during sleep similar to that obtained by a full night of ABPM (i.e., using ABPM throughout an entire night) when BP is not sampled randomly. Using data from participants in the Jackson Heart Study (JHS) and the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, we evaluated 74 variations in the number and timing of BP measurements during sleep to assess whether a limited number of BP measurements taken at specific times could provide an accurate estimate of mean BP from a full night of ABPM. From the complete set of ABPM measurements taken during sleep, subsets of two to four BP measurements at specific times were selected to represent HBPM during sleep. BP sampling variations were defined by the number and timing of the selected measurements.

Methods

Study population

The JHS, a community-based prospective cohort study, was designed to evaluate the etiology of CVD among African Americans [21]. The JHS enrolled 5306 noninstitutionalized African Americans aged ≥ 21 years from the Jackson, MS metropolitan area between 2000 and 2004. At the baseline JHS visit, 1146 participants volunteered to undergo ABPM. The CARDIA study was designed to examine the development and determinants of clinical and subclinical CVD and their risk factors [22]. The CARDIA study enrolled 5115 participants, 18–30 years of age, at four field centers in the USA (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA) in 1985–1986. During the Year 30 Exam (2015–2016), 831 CARDIA participants volunteered for an ABPM ancillary study conducted in the Birmingham, AL, and Chicago, IL, field centers.

We included participants who slept ≥ 5 h and recorded ≥ 1 valid asleep BP measurement every 30 min from midnight to 5:00 a.m. during their ABPM assessment (N = 621 JHS and 458 CARDIA participants; Supplementary Table 1). The conduct of each study was approved by institutional review boards at the participating institutions, and the current analysis was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Ambulatory BP monitoring

In the JHS, ABPM was conducted using the validated Spacelabs model 90207 device (Spacelabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, WA), and BP was measured every 20 min over a 24-h period [23]. JHS participants self-reported the times they went to sleep and woke up while wearing the ABPM device. In CARDIA, ABPM was conducted using the validated Spacelabs OnTrak model 90227 device (Spacelabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, WA), and BP was measured every 30 min over a 24-h period [24]. CARDIA participants also wore an Actiwatch activity monitor (Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA) on the wrist of their nondominant arm. In CARDIA, awake and asleep time periods were determined using the activity monitor data in conjunction with participants’ self-reported awake and asleep times. Nocturnal hypertension was defined by a mean SBP ≥ 120 mmHg or mean DBP ≥ 70 mmHg based on all BP measurements during sleep.

BP sampling strategies and variations

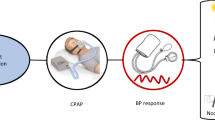

We considered both “distributed” and “consecutive” strategies for sampling BP during sleep (Fig. 1). The distributed strategies sampled BP at fixed intervals of 1 h or more. Consecutive strategies sampled consecutive BP measurements. We considered 25 distributed and 12 consecutive BP sampling variations and implemented each variation using either hours since midnight or hours since falling asleep. Overall, we assessed a total of 74 variations.

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and albuminuria

Echocardiograms and urine specimens were obtained during the Year 30 Exam for CARDIA participants and during the baseline study visit for JHS participants. Left ventricular mass was determined and indexed to body surface area to obtain left ventricular mass index (LVMI) according to recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging [25]. LVH was defined as LVMI > 95 g/m2 in women and >115 g/m2 in men. Urinary albumin and creatinine excretion, measured from urine specimens, were used to calculate the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). ACR was quantified using a 24-h urine sample in the JHS, if available. Otherwise, a spot urine sample was used. In CARDIA, a spot urine sample was collected. Albuminuria was defined as an ACR ≥ 30 mg/g.

Statistical analyses

Participant characteristics were summarized for the overall population and stratified by cohort. Differences between cohorts were assessed using t-tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The mean and standard deviation of SBP and DBP according to each BP sampling variation were computed along with the mean SBP and DBP according to a full night of ABPM. Linear regression with a natural cubic spline was applied to visualize the mean SBP and DBP over time from midnight to 5 a.m. and from onset of sleep to 5 h later among CARDIA and JHS participants.

Evaluation of 74 BP sampling variations

We computed the chance-corrected agreement (i.e., kappa statistic) for the presence of nocturnal hypertension between each BP sampling variation and the full night of ABPM. The mean absolute difference in mean SBP and DBP during sleep between each BP sampling variation and full night of ABPM was also computed. The 74 BP sampling variations were grouped into 12 categories based on the number of measurements, sampling strategy (i.e., consecutive or distributed), and time structure (i.e., time since midnight or time since falling asleep; Supplementary Table 2). Within each category, we defined the best variation as the one that obtained the highest kappa statistic. We applied bootstrap resampling to estimate differences in kappa statistics between BP sampling variations. We focused on kappa statistic differences where at least one variation sampled BP at 2, 3, and 4 h after falling asleep or midnight, as these two variations have been used in previous studies and are applied by some HBPM devices [13,14,15,16,17]. We also conducted pairwise comparisons of kappa statistics among the 12 best BP sampling variations of their category. Bootstrap resampling was applied using bias correction and acceleration [26].

Prevalence ratios and concordance

Poisson regression with robust standard error estimation was applied to obtain prevalence ratios and concordance (C-statistic) for the outcomes of LVH and albuminuria [27]. Models were fit using SBP and DBP from the full night of ABPM and using SBP and DBP from the best BP sampling variations within the categories described above. DeLong’s test was applied to assess whether individual BP sampling variations obtained different C-statistics for LVH or albuminuria compared to a full night of ABPM [28]. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, diabetes, antihypertensive medication use, and sleep duration. Models fitted to the pooled JHS and CARDIA data were additionally adjusted for cohort.

Consistency of results between the JHS and CARDIA

We calculated the Spearman rank order correlation coefficient for rankings of BP sampling variations by kappa statistic within the JHS and CARDIA studies. A high correlation between the rankings would indicate that BP sampling variations were ranked similarly in the two studies, i.e., that the results were consistent across the two studies.

Analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.0 (Vienna, Austria) and several additional R packages [29,30,31,32,33]. The code for the current analysis is available at https://github.com/bcjaeger/number-and-timing-of-ABPM. Data to replicate the current analysis can be requested from the JHS and CARDIA study executive committees.

Results

Among the 1079 participants included in the current analysis, the mean (standard deviation; SD) age was 57.1 (8.57) years, 32.0% were male and 81.0% were black. Among JHS and CARDIA participants, the mean (SD) asleep SBP was 120 (14.7) mmHg and 111 (15.1) mmHg, respectively (Table 1; p < 0.001), and the mean (SD) asleep DBP was 67.8 (9.16) mmHg and 66.3 (8.59) mmHg, respectively (p = 0.006). There was no evidence of a difference in the prevalence of LVH (p = 0.336) or albuminuria (p = 0.290) between JHS and CARDIA participants. Most BP sampling variations underestimated the mean SBP and DBP according to a full night of ABPM by 1–2 mmHg (Supplementary Table 3). Visualizations of SBP and DBP during sleep are presented in Figs. S1 and S2.

Evaluation of 74 BP sampling variations

Supplementary Table 4 presents kappa statistics and mean absolute differences for all 74 BP sampling variations compared with mean BP from a full night of ABPM. In the pooled cohort, 14 BP sampling variations obtained an estimated kappa for nocturnal hypertension statistic ≥ 0.80. There was substantial variation in the kappa statistic depending on the timing of BP measurements; for example, among BP sampling variations with three measurements using hours after falling asleep or after midnight, kappa statistics ranged from 0.69 to 0.83 and from 0.69 to 0.81, respectively. In particular, kappa statistics (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) from sampling variations used in prior studies—sampling BP at 2, 3, and 4 h after falling asleep or after midnight—were 0.81 (0.78, 0.85) and 0.77 (0.73, 0.81), respectively. Neither of these BP variations were among those that obtained the highest kappa statistic within their respective categories, which are presented in Table 2. Sampling BP at 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep or after midnight obtained kappa statistics (95% CI) of 0.84 (0.81, 0.87) and 0.82 (0.78, 0.85), respectively. For the sampling variation with the highest kappa statistic in the pooled cohort—BP sampled at 1, 2, 4 and 5 h after falling asleep—participants asleep SBP and DBP differed by an average of 3.11 (95% CI 2.97, 3.26) and 2.66 (95% CI 2.53, 2.78) mmHg, respectively, from the corresponding asleep BPs calculated from a full night of ABPM. For SBP, this was the lowest mean absolute difference obtained by any of the BP sampling variations.

The sampling variation with the highest kappa statistic among those that used three BP measurements—BP sampled at 1, 2, and 4 h after falling asleep—obtained a 0.02 (95% CI −0.03, 0.08) higher kappa statistic among CARDIA participants but a −0.01 (95% CI −0.05, 0.05) lower kappa among JHS participants compared to sampling BP at 2, 3, and 4 h after falling asleep (Table 3). Sampling BP at 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep resulted in 0.03 (95% CI −0.02, 0.08) and 0.03 (95% CI −0.03, 0.09) higher kappa statistics in the JHS and CARDIA, respectively, compared to sampling BP at 2, 3, and 4 h after falling asleep. Pairwise comparisons of kappa statistics between each category indicated that, in both cohorts, distributed sampling variations exhibited higher agreement with a full night of ABPM than consecutive variations (Figs. S3 and S4). In addition, in CARDIA, using four instead of three BP measurements resulted in a statistically significant increase in the kappa statistic when time was measured in hours since midnight.

Prevalence ratios and concordance

The prevalence ratios (95% CI) for LVH associated with a 10 mmHg higher mean asleep SBP according to a full night of ABPM or BP sampled 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling sleep were 1.22 (1.02, 1.46) and 1.24 (1.04, 1.48), respectively (Table 4). The C-statistics for mean asleep SBP according to a full night of ABPM or BP sampled 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep were 0.712 (0.659, 0.765) and 0.705 (0.651, 0.760), respectively (p value for difference: 0.31; Table 5).

The prevalence ratios (95% CI) for albuminuria associated with a 10 mmHg higher mean asleep SBP according to a full night of ABPM or BP assessed 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep were 1.27 (1.07, 1.52) and 1.35 (1.15, 1.60), respectively (Supplementary Table 5). The C-statistics for mean asleep SBP from a full night of ABPM and for BP assessed 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep were 0.774 (0.719, 0.829) and 0.776 (0.720, 0.832), respectively (p value for difference: 0.72; Supplementary Table 6).

Consistency of results between the JHS and CARDIA

The correlations between the JHS and CARDIA cohort rankings of BP sampling variations according to the mean absolute difference in SBP, mean absolute difference in DBP, and kappa statistics were 0.92, 0.93, and 0.78, respectively.

Discussion

In the current study, the highest kappa statistic assessing agreement with nocturnal hypertension based on a full ABPM assessment and the lowest mean absolute difference for estimating mean SBP during sleep resulted from sampling BP at 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep. The prevalence ratios for LVH and albuminuria based on sampling BP at these times were slightly higher than prevalence ratios based on the full night of ABPM. There was no evidence that the ability of sleep BP based on this sampling variation to discriminate (i.e., C-statistic) those with versus without LVH or albuminuria was different than sleep BP based on a full night of ABPM. The low mean absolute differences of 3.1 and 2.7 mmHg for SBP and DBP, respectively, when sampling BP at 1, 2, 4, and 5 h after falling asleep suggests that this approach may be a suitable method to approximate mean BP according to a full night of ABPM. The high correlation of kappa statistics and mean absolute difference rankings for the 74 BP sampling variations in CARDIA and the JHS indicated that the results were consistent across the two cohorts, suggesting that findings from the current study were not overly influenced by a single cohort.

Yang et al. and Rinfret et al. independently investigated how many BP readings should be collected to obtain a reasonably accurate estimate of mean daytime and nighttime BP or mean BP using HBPM twice in the morning and twice in the evening for 1 week [19, 20]. Each analysis examined scenarios where BP measurements were randomly sampled from a larger set of BP measurements. Yang et al. concluded that randomly measuring BP four times during sleep versus measuring BP throughout sleep does not lead to a meaningful loss of information in hypertension categorization or risk stratification [19]. The current results are consistent with findings from Yang et al., indicating that four BP measurements are sufficient for estimating BP during sleep but further demonstrating that the timing of BP measurements substantially impacts the accuracy of mean BP during sleep. Given that 24 BP measurements are expected during 8 h of sleep with one measurement every 20 min, collecting only four BP measurements at select times may substantially lower sleep disturbance without meaningful loss of information.

Sleep disturbance is a known side effect of ABPM for some individuals [34]. A previous study evaluating the acceptability of an ABPM device among 110 pregnant women found that 28.8% reported difficulty initiating sleep with ABPM, 56.3% reported difficulty maintaining sleep with ABPM, and sleep disturbance was associated with increased odds of discontinuing ABPM (odds ratio for discontinuation: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.23, 2.27). Waking due to the inflation of ABPM cuffs can also increase BP and falsely suggest BP does not decline during sleep, an ABPM phenotype known as nondipping [35]. The current study introduces strategies that may reduce sleep disturbance by reducing the number of BP measurements taken during sleep. In total, 14 BP sampling variations obtained an estimated kappa for nocturnal hypertension statistic ≥ 0.80, suggesting strong agreement with a full night of ABPM. These results suggest that devices can be designed with a large set of valid sampling options to estimate mean BP during sleep.

In the Japan Morning Surge Home Blood Pressure (J-HOP) study, mean BP from a self-measured HBPM device programmed to measure BP at 2, 3, and 4 a.m. was associated with LVMI and ACR, independent of clinical BP and home BP during the morning and evening [15]. The current study confirms these results by showing that BP measured two to four times using ABPM during sleep is associated with LVH and albuminuria in other cohorts. Another analysis of the J-HOP data found that the average of BP readings assessed at 2, 3, and 4 a.m. over an average of 8.89 nights using the same HBPM device was associated with incident CVD events but found no evidence of an association between mean BP from a single night of ABPM and CVD [36]. The current study found a mean absolute difference of ~4 mmHg in SBP between a full night of ABPM and measuring BP at 2, 3, and 4 a.m.. Future studies should identify whether the additional prognostic value of HBPM versus ABPM for incident CVD risk persists when both techniques are repeated over multiple nights.

The current study assessed sampling variations in BP at specific times relative to midnight and sleep onset. Although both approaches are valid, the latter may be more likely to adequately measure BP during sleep in samples where participants go to sleep at a range of times. Study participants may also prefer the latter definition, as it does not require them to be asleep at specific times. Future studies should investigate the reliability of and preference for HBPM devices that are programmed to measure BP at times relative to midnight versus relative to the onset of sleep.

Visualizations of SBP and DBP during sleep from the current study (see Figs. S1 and S2) suggest that BP measured 2, 3, and 4 h or 1, 2, 4 and 5 h after falling asleep may be important for diagnosing nocturnal hypertension because these sampling times tend to coincide with the period of sleep when BP is dipping, rising, or at its minimum point during sleep. Sampling BP at these times may yield mean BP values that are closest to that of full ABPM because they average over both the diurnal pattern and diurnal fluctuations in BP during sleep, i.e., they capture the U-shaped BP curve that usually occurs during sleep. Future studies should investigate the association between mean BP across these sampling times and outcomes that are associated with nocturnal hypertension, such as CVD and all-cause mortality [37, 38].

The current study has several strengths. We analyzed data from two cohorts that collected ABPM data. We investigated a comprehensive set of variations for sampling BP during sleep, allowing us to identify several variants that exhibited high agreement with full ABPM. We conducted analyses separately by cohort, and the parallel assessment of each BP sampling variant reduced the likelihood of finding spurious results that would not generalize to broader settings. In addition, the current study has some limitations. While sleep was monitored using actigraphy in the CARDIA cohort, the JHS relied on self-reported sleep diaries to identify awake and asleep times. Due to strict inclusion criteria, especially the requirement that there be a valid BP reading every 30 min between midnight and 5 a.m., the current study excluded a substantial proportion of participants from each cohort. The results from the current study may not generalize to settings where participants sleep for <5 h or miss planned BP measurements, e.g., older adults who typically wake up early and often do not sleep for 5 consecutive hours.

In conclusion, measuring BP three or four times during sleep with at least 1 h between measurements may provide mean asleep BP estimates that have high agreement with a full night of ABPM and are similarly predictive of target organ damage. Future studies may choose to measure BP three to four times during sleep instead of 16 or more times that occurs with a full night of ABPM, as this could improve study recruitment and increase the likelihood of participants agreeing to have their sleep BP assessed over multiple nights. The results from the current study also suggest that HBPM devices programmed to measure BP at specific times during sleep or after midnight may be a reasonable substitute for a full night of ABPM.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

O’Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, et al. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731–68.

Parati G, Stergiou G, O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Bilo G, et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1359–66.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Friedman O, Logan AG. Can nocturnal hypertension predict cardiovascular risk? Integr Blood Press Control. 2009;2:25 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3172086/.

Yano Y, Tanner RM, Sakhuja S, Jaeger BC, Booth JN, Abdalla M, et al. Association of daytime and nighttime blood pressure with cardiovascular disease events among African American individuals. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:910–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2845.

Kario K. Nocturnal hypertension: new technology and evidence. Hypertension. 2018;71:997–1009.

Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2368–74.

Kario K, Hoshide S, Chia Y-C, Buranakitjaroen P, Siddique S, Shin J, et al. Guidance on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: a statement from the HOPE Asia Network. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23:411–21.

Ernst ME, Bergus GR. Favorable patient acceptance of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in a primary care setting in the United States: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2003;4:15.

Degaute JP, Kerkhofs M, Dramaix M, Linkowski P. Does non-invasive ambulatory blood pressure monitoring disturb sleep? J Hypertens. 1992;10:879–85.

Agarwal R, Light RP. The effect of measuring ambulatory blood pressure on nighttime sleep and daytime activity—implications for dipping. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:281–5.

Gaffey AE, Schwartz JE, Harris KM, Hall MH, Burg MM. Effects of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring on sleep in healthy, normotensive men and women. Blood Press Monit. 2021;26:93–101.

Stergiou GS, Nasothimiou EG, Destounis A, Poulidakis E, Evagelou I, Tzamouranis D. Assessment of the diurnal blood pressure profile and detection of non-dippers based on home or ambulatory monitoring. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:974–8.

Ishikawa J, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, Ishikawa S, Shimada K, Kario K, et al. Nighttime home blood pressure and the risk of hypertensive target organ damage. Hypertension. 2012;60:921–8.

Kario K, Hoshide S, Haimoto H, Yamagiwa K, Uchiba K, Nagasaka S, et al. Sleep blood pressure self-measured at home as a novel determinant of organ damage: Japan Morning Surge Home Blood Pressure (J-HOP) study. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17:340–8.

Ishikawa J, Shimizu M, Edison ES, Yano Y, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, et al. Assessment of the reductions in night-time blood pressure and dipping induced by antihypertensive medication using a home blood pressure monitor. J Hypertens. 2014;32:82–9.

Fujiwara T, Tomitani N, Kanegae H, Kario K. Comparative effects of valsartan plus either cilnidipine or hydrochlorothiazide on home morning blood pressure surge evaluated by information and communication technology–based nocturnal home blood pressure monitoring. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:159–67.

Kario K, Saito I, Kushiro T, Teramukai S, Ishikawa Y, Mori Y, et al. Home blood pressure and cardiovascular outcomes in patients during antihypertensive therapy: primary results of HONEST, a large-scale prospective, real-world observational study. Hypertension. 2014;64:989–96.

Yang W-Y, Thijs L, Zhang Z-Y, Asayama K, Boggia J, Hansen TW, et al. Evidence-based proposal for the number of ambulatory readings required for assessing blood pressure level in research settings: an analysis of the IDACO database. Blood Press. 2018;27:341–50.

Rinfret F, Ouattara F, Cloutier L, Larochelle P, Ilinca M, Lamarre-Cliche M. The impact of unrecorded readings on the precision and diagnostic performance of home blood pressure monitoring: a statistical study. J Hum Hypertens. 2018;32:197–202.

Taylor HA Jr, Wilson JG, Jones DW, Sarpong DF, Srinivasan A, Garrison RJ, et al. Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African Americans: design and methods of the Jackson Heart Study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:S6–4.

Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–16.

O’Brien E, Mee F, Atkins N, O’Malley K. Accuracy of the SpaceLabs 90207 determined by the British Hypertension Society protocol. J Hypertens. 1991;9:S25–31.

de Greeff A, Shennan AH. Validation of the Spacelabs 90227 OnTrak device according to the European and British Hypertension Societies as well as the American protocols. Blood Press Monit. 2020;25:110–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/MBP.0000000000000424.

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–71.

Efron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:171–85.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6.

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2021. https://www.R-project.org/.

Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan L, François R, et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4:1686.

Landau WM. The drake R package: a pipeline toolkit for reproducibility and high-performance computing. J Open Source Softw. 2018;3:550. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00550.

Buuren S van, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67.

Jaeger B. table.glue: make and apply customized rounding specifications for tables. R package version 0.0.2. https://github.com/bcjaeger/table.glue/.

Steen MS van der, Lenders JW, Thien T. Side effects of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:151–5.

Agarwal R, Light RP. The effect of measuring ambulatory blood pressure on nighttime sleep and daytime activity—implications for dipping. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:281–5.

Mokwatsi GG, Hoshide S, Kanegae H, Fujiwara T, Negishi K, Schutte AE, et al. Direct comparison of home versus ambulatory defined nocturnal hypertension for predicting cardiovascular events: the Japan morning surge-home blood pressure (J-HOP) study. Hypertension. 2020;76:554–61.

Kario K, Yano Y. Nocturnal blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: a review of recent advances. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:695. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.26.

Yano Y, Tanner RM, Sakhuja S, Jaeger BC, Booth JN, Abdalla M, et al. Association of daytime and nighttime blood pressure with cardiovascular disease events among African American individuals. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:910–7.

Acknowledgements

The JHS is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University (HHSN268201800013I), Tougaloo College (HHSN268201800014I), the Mississippi State Department of Health (HHSN268201800015I/HHSN26800001), and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (HHSN268201800010I, HHSN268201800011I, and HHSN268201800012I) contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors also wish to thank the staff and participants of the JHS. The CARDIA study is conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201800005I and HHSN268201800007I), Northwestern University (HHSN268 201800003I), University of Minnesota (HHSN2682018000 06I), and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201 800004I). Funding to conduct ambulatory BP monitoring in the CARDIA study was provided by grant 15SFRN2390002 from the American Heart Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by PM, JES, DS, and BCJ. Data analysis and interpretation were conducted by BCJ, OPA, SS, JDB, CEL, YY, GH, DS, PM, and JES. The manuscript was written and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaeger, B.C., Akinyelure, O.P., Sakhuja, S. et al. Number and timing of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring measurements. Hypertens Res 44, 1578–1588 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00717-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00717-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Development of beat-by-beat blood pressure monitoring device and nocturnal sec-surge detection algorithm

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

High versus low measurement frequency during 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring - a randomized crossover study

Journal of Human Hypertension (2023)

-

Nächtlicher Hypertonus

CardioVasc (2022)

-

Accurate nighttime blood pressure monitoring with less sleep disturbance

Hypertension Research (2021)