Abstract

The need to enhance the quality of life and functionality of patients with a number of diseases, such as congenital abnormalities, traumas, and gender incongruence, has contributed to a significant development in the field of male genital reconstructive surgery. This article highlights the roots of penile reconstructive surgeries over history, emphasizing innovative achievements that have shaped modern practices. Critical advancements that have improved surgical accuracy and post-operative care are examined, including new imaging modalities, penile prosthesis implantation, and complete phallic reconstruction. In terms of future improvements in genital reconstructive surgery, the combination of tissue engineering and microsurgery offers the potential to further improve the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evolution of male genital reconstructive surgery has been significantly shaped by the necessity to improve the quality of life and functionality for patients dealing with conditions such as hypospadias, epispadias, urethral strictures, penile curvature, penile cancer, traumatic injuries, congenital abnormalities, and gender incongruence.

Penile reconstructive surgery traces its origins back to ancient procedures such as the surgical treatment of phimosis by the Greek physician Aegineta [1]. The field has seen significant advancements since the efforts of pioneers including Dr. Nikolaj A. Bogoraz [2], Sir Harold Gillies [3], Dr. Reed M. Nesbit [4], and Dr. Ti-Sheng Chang [5] in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In modern times, these developments have been propelled further by the rising need and numbers of gender affirmation surgery, leading to more refined and effective reconstructive techniques.

As the field progresses, ethical considerations have also drawn more attention, especially in procedures like penile augmentation. Clinical guidelines now emphasize the importance of addressing conditions such as Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Penile Dysmorphic Disorder, which can affect surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction. Therefore, incorporating comprehensive psychological assessments has become vital to ensure safe and successful intervention [6].

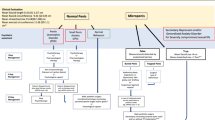

This article discusses critical advances across specific areas, including total phallic reconstruction, which focuses on achieving a cosmetically acceptable and functional phallus optimal for both urinary and sexual function. Recent advancements in genital reconstructive surgery also address conditions like Adult-Acquired Buried Penis (AABP), improving functional outcomes and patient satisfaction through refined techniques. It also examines the complexities and pivotal role of penile prosthesis implantation for erectile function, especially following masculinising gender-affirming surgery or in men with Peyronie’s disease with concurrent erectile dysfunction.

Furthermore, we cover the significant advancements in the surgical treatment of penile cancer, noting a shift towards more conservative surgical approaches to better preserve penile function and appearance. The role of advanced imaging modalities, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is also discussed, highlighting how they have improved both pre-operative planning and post-operative care in detecting and managing complications, thereby enhancing surgical precision and patient care.

The future of penile reconstructive surgery promises even greater advancements with the integration of cutting-edge technologies such as microsurgical technique and tissue engineering, which aim to further enhance the precision, safety, and outcomes of these complex procedures. The aim of this perspective article is to enrich our understanding of the dynamic field of modern penile reconstruction surgery and its ongoing commitment to technological integration and procedural refinements, giving us clues about what awaits us in the future.

Advancement in grafting materials

Early reconstructive surgeries were limited by the availability and compatibility of grafting materials. However, synthetic and biocompatible materials have revolutionised the field, offering diverse options to surgeons.

The use of biological materials in reconstructive surgeries has overcome some challenges of synthetic grafts by enhancing biocompatibility and tissue integration. Historically, synthetic polyethylene terephthalate (PETE) and politetrafloroetilen (PTFE) grafts were among the few options but carried risk of infection, inflammatory reaction, and fibrosis [7]. Autologous tissues, like buccal mucosa, saphenous vein, and tunica albuginea, have become preferred grafts for their biocompatibility. 8 Additionally, decellular matrix is widely used acting as a scaffold for tissue regeneration [8].

Xenografts and allografts, processed tissues from animal and cadaveric sources, expand options for complex surgeries. Xenografts, from porcine, bovine, etc., mimic human tissue structure, enhance tissue integration and promote cellular ingrowth [9]. However, resorption rates vary, potentially affecting the long-term success and stability of surgical repairs [10]. Faster resorption might compromise structural support, while delayed resorption might lead to fibrosis, affecting natural feel and flexibility [10].

Significant advancements in tissue processing such as chemical cross-linking and decellularization techniques, date back to the 1960s. These developments improved biocompatibility and reduced antigenicity, thereby enhancing graft success rates [11]. These developments set the stage for introducing porcine small intestinal submucosa and pericardial grafts, which supports cell proliferation, tissue remodelling, and vascularization at the graft site, in reconstructive urology [12, 13]. TachoSil ® (Corza Medical, MA, USA), an equine collagen fleece with human fibrinogen and thrombin, promotes haemostasis and wound healing, particularly useful in Peyronie’s disease correction [14]. Building on these developments, acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) have become as transformative tools for reconstructing donor sites, providing superior healing, aesthetics, and lower morbidity compared to traditional grafts (split and full thickness skin grafts) [15]. ADMs, used in combination with split-thickness skin grafts, demonstrate higher graft take rates (93.8% vs. 27.8%, p = 0.001), faster healing times (24 days vs. 30 days, p = 0.003), shorter operative durations, and greater patient satisfaction compared to full-thickness skin grafts, especially in procedures like radial forearm free flap phalloplasty [15,16,17]. These developments exemplify the diversification and refinement of xenograft materials, including hybrid materials integrating bioactive molecules or stem cells.

Advancements in penile straightening procedures

The evolution to contemporary penile straightening procedures reflects an improved understanding Peyronie’s disease, innovative techniques, improved grafting materials.

Early surgical attempts to correct penile curvature began in the late 19th century with plaque excision by MacClellan, Regnoli and Huitfeldt [18]. These were isolated cases and lacked standardization [18]. By the early 20th century, the treatment of this disease involved plaque excision followed by the placement of dermal grafts, fat, or fascia over defect to restore penile function and appearance. Lowsley and Boyce reported 60% success rate but also over 20% of recurrence rate among patients with this technique [19].

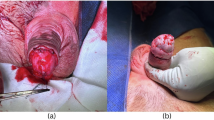

A breakthrough advance occurred in 1965 with the Nesbit’s procedure [4]. This technique became foundational for curvature correction. The procedure involves excision and plication of the tunica albuginea opposite the curvature, straightening the penis (Fig. 1A).

A Attenuated Nesbit procedure in a patient with dorsal curvature, B Plication procedure in a patient with left-sided curvature, C Lue Procedure of a patient with dorsal side curvature. Artificial erection confirms the correction of the penis, D Curvature assessment with artificial erection, E Left-sided vertical incision of ventral surface of the left corporeal body of the penis. This incision will be closed in a transvers fashion afterward.

Following the Nesbit’s procedure, various modifications emerged to reduce complications. Less invasive techniques like the Essed-Schroder plication [20] and the Lue 16-dot technique [21], introduced plications without tunica albuginea excision, reducing the risk of erectile dysfunction (Fig. 1B) Additionally, rotation techniques that cause minimal shortening of the penis length in the ventral curvatures have also been described [22].

For severe cases of Peyronie’s disease with significant curvature or risk of significant shortening with plication, another technique is to incise or excise the plaque and use grafts (autolog, allograft, xenograft, or synthetic) to fill the defects (Fig. 1C).

The Yachia technique modified the Nesbit procedure by using longitudinal incisions with transverse closures (Heineke-Mikulicz method), reducing erectile dysfunction risk and shortening operative time [23] (Fig. 1D, E).

Additionally, traction and vacuum devices gained popularity to reducing curvature and restoring penile length. Their increasing use indicates a growing preference for non-surgical methods [24].

In recent decades, minimally invasive treatment such as collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum injections have shown promise by dissolving collagen accumulations causing curvature and reducing the need for surgery [25]. Furthermore, Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment has also been explored as a treatment for Peyronie’s disease pain relief, while its efficacy in curvature remains uncertain [26].

Looking forward, research in tissue engineering and stem cell therapy, could improve both invasive and non-invasive therapies for penile deviation and Peyronie’s disease. These advancements appear promising for new methods to repair or regenerate tunica albuginea tissue, potentially reducing the need for surgery and enhance outcomes.

Phalloplasty techniques: evolution and current trends

The concept of phalloplasty dates back to the early 20th century, with initial procedures focused on treating injuries and congenital defects [2]. Early surgeries were rudimentary and primarily aimed to create a structure that resembled a penis, with limited focus on functionality or aesthetics [2].

In the mid-20th century, surgeons used tubed pedicle grafts, harvested from areas like the thigh, abdomen, or forearm, to construct a penis [2, 3]. In order to create the phallic structure, a skin graft was rolled into a tube and affixed to the pubic area. While this represented a significant advancement, results often lacked in appearance, sensation, and function [3, 27] (Fig. 2A, B).

The introduction of microsurgery in the 1980s revolutionized phalloplasty with free flap techniques. The radial artery forearm free-flap (RAFFF) has gained popularity, allowing for the transferring skin, fat, nerve, and vascular tissue from the forearm to create functional and natural-looking results [5]. This technique improved standing micturition and sensation prospects [5] (Fig. 3A).

Free flap techniques evolved with alternative donor sites, like the Anterolateral Thigh (ALT) and the Latissimus Dorsi (LD), reducing morbidity and enhancing aesthetics [28, 29] (Fig. 3B).

There are also improvements in the creation of the neo-urethra, allowing for more reliable standing micturition [30]. RAFFF urethral reconstruction gains popularity due to its benefit of introducing reliable, well-vascularized, and sensitive tissue [31] (Fig. 3C).

The ideal phalloplasty goal is to create a cosmetically acceptable and sensate phallus with an integrated neourethra, allowing the patient to void while standing and adequate bulk to accommodate a stiffener for sufficient rigidity for intercourse [32]. Stiffness techniques have included osteocutaneous flaps cartilage insertion during initial surgeries, but they often led to complications including rigidity issues, infection, and challenges in achieving and maintaining a natural appearance and functionality [33].

Implanting penile prostheses, especially inflatable types, has become an essential aspect of phalloplasty. Since Puckett and Montie introduced penile implantation in phalloplasty for gender dysphoria in 1978, the procedure has significantly improved functionality for transgender men [34]. However, it is acknowledged as complex with high complication rates, necessitating experienced surgeons in dedicated, high-volume centres [35]. Furthermore, testicular implants and scrotoplasty techniques have also seen advancements, enabling more precise reconstructions [36,37,38]. Recent advancements in scrotoplasty have introduced techniques such as the V-Y advancement of the labia majora and the Hoebeke method, which improve the anatomical and aesthetic outcomes of neoscrotal construction [36, 37]. Additionally, testicular prostheses, often implanted in a following procedure, now better replicate the size and shape of biological testicles, offering enhanced cosmetic and psychological benefits, though long-term clinical outcomes remain under-documented [38].

Advanced technologies, such as robotics and 3D printing, could improve phalloplasty techniques, particularly for phallus shaping [39, 40]. Emerging tissue engineering and regenerative medicine could eventually generate enable lab-grown penile tissue for transplantation [8]. Though still in their early phases, these methods hold promise for individuals needing sophisticated male genital reconstructive surgeries.

Advancements in penile cancer surgeries

The incidence of penile carcinoma has risen recently, although it is still rare, accounting for <1% of all male cancers. In the United Kingdom, there are around 350 new diagnoses of penile cancer annually, with an incidence of 1.1 per 100,000 [41].

Surgical treatments of penile cancer have evolved significantly, breakthroughs led by research looking at positive surgical margins and local recurrence rates, which has caused advancements over the years, focusing primarily on improving patient outcomes and preserving penile function [42].

Historically, extensive resections, including partial or total penectomy were common, severely impacting quality of life, particularly sexual function [43]. While amputation remains necessary in some cases, more conservative methods are now favoured, with safety margins progressively shortened [44]. Earlier practices required around 2 cm margins, but recent studies have demonstrated that even a few millimetres free margin can provide effective outcomes, preserving more healthy tissue and improving penile function and appearance [44] (Fig. 4A–C).

Penile preserving techniques, now a well-documented treatment for Tis, T1, and T2 tumours, offering better sexual and urinary function without compromising oncological safety or cancer-specific survival [45]. Advancements in reconstructive techniques, like split skin grafts, further enhance functional and cosmetic outcomes [42].

Looking forward, advancements in robotic and laser surgery, promise greater accuracy and less invasiveness [46, 47]. Emerging topical and intralesional treatments that will lessen the need for major surgeries [48]. These developments indicate a shift toward organ preservation and improved patient quality of life.

Adult-acquired buried penis (AABP): evolution of surgical techniques

The surgical management of AABP, a condition increasingly linked with the global rise in obesity [49], has evolved significantly in recent years [50]. AABP was an unappreciated condition in the past, leading to severe functional impairments in urinary and sexual function, psychological distress, and a worse quality of life [51]. Modern surgical developments have aimed to address these complex problems.

Recent studies highlight various techniques for AABP repair, including escutcheonectomy with or without skin grafting, liposuction, V-Y plasty, scrotoplasty, penoplasty with diamond-shaped incisions and concurrent panniculectomy with fascial reconstruction [50, 52,53,54]. According to Wang et al., “diamond-shaped penoplasty” combined with suprapubic liposuction have demonstrated enhanced penile length and aesthetic outcomes with little side effects [52]. The use of panniculectomy in conjunction with AABP repair has also improved functional and psychological results with similar rates of complications [53]. Additionally, split-thickness and full-thickness skin grafts used for AABP repair did not significantly differ in surgical, functional, or patient-reported outcomes, based on a recent comparative retrospective study by Gül et al., highlighting the benefits of both approaches in managing cases involving significant penile skin loss [55]. In order to enhance postoperative support and aesthetics, anatomic studies have refined fascial reconstruction including reapproximating the fundiform ligament [54].

Despite difficulties, particularly with obese patients, AABP surgery has changed as a result of developments in reconstruction, soft tissue excision, and grafting. These methods show the value of cooperation between urologic and plastic surgeons by restoring function and reducing the psychological and social problems associated with AABP. Long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction are the goals of continuous enhancements.

The role of imaging modalities in penile reconstruction

Imaging modalities are essential in male genital reconstructive surgery, serving diagnosis, pre-operative planning, and post-operative care. Techniques such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and particularly MRI offer vital insights into anatomical structures and clinical situations (Supplementary Figure).

Recognized for its detailed anatomical visualizations, MRI’s significance in medical diagnostics was initially established in the late 1980s [56]. It has proven highly effective at revealing normal anatomical features and various abnormalities such as congenital anomalies, penile prostheses complications, trauma-related alterations, Peyronie’s disease, and neoplasms, thereby significantly aiding in diagnosis and surgical planning [57]. MRI demonstrates outstanding performance across a wide range of genitourinary complex scenarios, staging penile cancer when physical examination results are unclear, assessing tissue viability in priapism, determining injuries in penile fractures, aiding in surgical planning for penile fibrosis and Peyronie’s disease, and potentially replacing urethrography in complex pelvic fractures [57, 58]. Furthermore, MRI plays a critical role in the management of complications in penile prosthesis, evaluating the positioning, configuration, and functional state of malleable and inflatable prostheses, and detecting problems like infection, mechanical failure, and malpositioning [59].

Future advances may include advanced MRI techniques, augmented reality for real-time surgical navigation, and machine learning algorithms to enhance surgical accuracy and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Significant advancements in male genital reconstructive surgery have improved patient outcomes and expanded treatment options through materials ranging from synthetic, biocompatible substances to tissue-engineered solutions and natural biological materials like xenografts. These materials, consist of porcine, bovine, and equine tissues, have structural benefits and affordability despite immunological responses and disease transmission risk. Innovations like TachoSil® demonstrate dedication to raising the standard and effectiveness of reconstructive surgeries. Meanwhile, the field of penile straightening has evolved toward refined, less invasive techniques, that preserve sexual function, reflecting a deeper understanding of conditions like Peyronie’s disease. Additionally, advancements in phalloplasty have paralleled these improvements, evolving from tubed pedicle grafts to sophisticated free flap microsurgical techniques that enhance structural, functional, and cosmetic results. While the evolution of penile prosthesis surgeries, particularly for patients undergoing phalloplasty, has achieved greater functionality, and patient satisfaction. Furthermore, penile cancer surgeries emphasize conservative approaches prioritizing organ function and preservation. The future of these reconstructive treatments looks promising with advancements in regenerative medicine, offering potential to overcome current limitations.

References

Gurunluoglu R, Gurunluoglu A. Paulus Aegineta, a seventh century encyclopedist and surgeon: his role in the history of plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2072–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200112000-00038

Bogoras N, Don RA. Uber die volle plastische Wiederherstellung eines sum Koitus fahigen Penis (Peniplastica totalis). Zentralbl Chir. 1936;22:1271–5.

Gillies H. Congenital absence of the penis. Br J Plast Surg. 1948;1:8–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0007-1226(48)80006-8

Nesbit RM. Congenital curvature of the phallus: report of three cases with description of corrective operation. J Urol. 1965;93:230–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63751-0

Chang T-S, Hwang WY. Forearm flap in one-stage reconstruction of the penis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:251.

Falcone M, Bettocchi C, Carvalho J, Ricou M, Boeri L, Capogrosso P, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on penile size abnormalities and dysmorphophobia: summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur Urol Focus. 2024;10:432–41.

Brannigan RE, Kim ED, Oyasu R, McVary KT. Comparison of tunica albuginea substitutes for the treatment of Peyronie’s disease. J Urol. 1998;159:1064–8.

Elia E, Caneparo C, McMartin C, Chabaud S, Bolduc S Tissue engineering for penile reconstruction. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024;11:230. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11030230

Santucci RA, Barber TD. Resorbable extracellular matrix grafts in urologic reconstruction. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:192–203. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-55382005000300002.

Kadioglu A, Sanli O, Akman T, Ersay A, Guven S, Mammadov F. Graft materials in Peyronie’s disease surgery: a comprehensive review. J Sex Med. 2007;4:581–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00461.x.

Rosenberg N, Martinez A, Sawyer PN, Wesolowski SA, Postlethwait RW, Dillon ML Jr. Tanned collagen arterial prosthesis of bovine carotid origin in man. Preliminary studies of enzyme-treated heterografts. Ann Surg. 1966;164:247–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-196608000-00010.

Lee EW, Shindel AW, Brandes SB. Small intestinal submucosa for patch grafting after plaque incision in the treatment of Peyronie’s disease. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:191–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-55382008000200009

Hellstrom WJG, Reddy S. Application of pericardial graft in the surgical management of Peyronie’s disease. J Urol. 2000;163:1445–7.

Horstmann M, Kwol M, Amend B, Hennenlotter J, Stenzl A. A self-reported long-term follow-up of patients operated with either shortening techniques or a TachoSil grafting procedure. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:326–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/aja.2010.157

Falcone M, Preto M, Ciclamini D, Peretti F, Scarabosio A, Blecher G, et al. Bioengineered dermal matrix (Integra®) reduces donor site morbidity in total phallic construction with radial artery forearm free-flap. Int J Impot Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00775-5

Wagstaff MJ, Schmitt BJ, Coghlan P, Finkemeyer JP, Caplash Y, Greenwood JE. A biodegradable polyurethane dermal matrix in reconstruction of free flap donor sites: a pilot study. Eplasty. 2015;15:e13.

Lee WG, Christopher AN, Ralph DJ. Commentary: Bioengineered dermal matrix reduces donor site morbidity in total phallic construction with RAFFF. Int J Impot Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-024-00953-z.

Keyes EL Phimosis; paraphimosis; tumours of the penis. In Urology. 1st edn. New York D. Appleton and Company, 1928: 640-2.

Lowsley OS, Boyce WH. Further experiences with an operation for the cure of Peyronie’s disease. J Urol. 1950;63:888–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)68843-8

Essed E, Schroeder FH. New surgical treatment for Peyronie disease. Urology. 1985;25:582–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-4295(85)90285-7.

Gholami SS, Lue TF. Correction of penile curvature using the 16-dot plication technique: a review of 132 patients. J Urol. 2002;167:2066–9.

Shaeer O, Shaeer K. Shaeer’s corporal rotation IV: length-preserving correction of congenital ventral penile curvature. J Sex Med. 2023;20:699–703. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsxmed/qdad028

Yachia D. Modified corporoplasty for the treatment of penile curvature. J Urol. 1990;143:80–82.

Avant RA, Ziegelmann M, Nehra A, Alom M, Kohler T, Trost L. Penile traction therapy and vacuum erection devices in Peyronie’s disease. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:338–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.02.005

Gelbard M, Lipshultz LI, Tursi J, Smith T, Kaufman G, Levine LA. Phase 2b study of the clinical efficacy and safety of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum in patients with Peyronie disease [published correction appears in J Urol. 2012 Aug;188:678]. J Urol. 2012;187:2268–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.032

Spirito L, Manfredi C, La Rocca R, Napolitano L, Preto M, Di Girolamo A, et al. Long-term outcomes of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for acute Peyronie’s disease: a 10-year retrospective analysis. Int J Impot Res. 2024;36:135–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00673-w

Bettocchi C, Ralph DJ, Pryor JP. Pedicled pubic phalloplasty in females with gender dysphoria. BJU Int. 2005;95:120–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05262.x

Felici N, Felici A. A new phalloplasty technique: the free anterolateral thigh flap phalloplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:153–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2005.05.016

Djordjevic ML, Bencic M, Kojovic V, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Kojic S, et al. Musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap for phalloplasty in female to male gender affirmation surgery. World J Urol. 2019;37:631–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-02641-w

Harrison DH. Reconstruction of the urethra for hypospadiac cripples by microvascular free flap transfers. Br J Plast Surg. 1986;39:408–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-1226(86)90057-3

Dabernig J, Shelley OP, Cuccia G, Schaff J. Urethral reconstruction using the radial forearm free flap: experience in oncologic cases and gender reassignment. Eur Urol. 2007;52:547–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.004

Garaffa G, Christopher NA, Ralph DJ. Total phallic reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals. Eur Urol. 2010;57:715–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.018

Kim SK, Kim TH, Yang JI, Kim MH, Kim MS, Lee KC. The etiology and treatment of the softened phallus after the radial forearm osteocutaneous free flap phalloplasty. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:390–6. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2012.39.4.390

Puckett CL, Montie JE. Construction of male genitalia in the transsexual, using a tubed groin flap for the penis and a hydraulic inflation device. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:523–30.

Wang AMQ, Tsang V, Mankowski P, Demsey D, Kavanagh A, Genoway K. Outcomes following gender affirming phalloplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Med Rev. 2022;10:499–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2022.03.002

Hage JJ, Bouman FG, Bloem JJ. Constructing a scrotum in female-to-male transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:914–21.

Selvaggi G, Hoebeke P, Ceulemans P, Hamdi M, Van Landuyt K, Blondeel P, et al. Scrotal reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals: a novel scrotoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1710–8.

Hayon S, Michael J, Coward RM. The modern testicular prosthesis: patient selection and counseling, surgical technique, and outcomes. Asian J Androl. 2020;22:64–69. https://doi.org/10.4103/aja.aja_93_19

Doersch KM, Kong L, Kaoutzanis C, Higuchi T. The role of the surgical robot in gender-affirming surgery: a scoping review. Ther Adv Urol. 2025;17:17562872251336639. https://doi.org/10.1177/17562872251336639

Walker MW, Kaoutzanis C, Jacobson NM. 3D printing for an anterolateral thigh phalloplasty. 3D Print Med. 2023;9:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41205-023-00200-z

Sewell J, Ranasinghe W, De Silva D, Ayres B, Ranasinghe T, Hounsome L, et al. Trends in penile cancer: a comparative study between Australia, England and Wales, and the US. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:420.

Kristinsson S, Johnson M, Ralph D. Review of penile reconstructive techniques. Int J Impot Res. 2021;33:243–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-020-0246-4

Romero FR, Richter Pereira Dos Santos Romero K, de Mattos MAE, Camargo Garcia CR, de Carvalho Fernandes R, Cardenuto Perez MD. Sexual function after partial penectomy for penile cancer. Urology. 2005;66:1292–5.

Pang KH, Muneer A, Alnajjar HM. Glansectomy and reconstruction for penile cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol Focus. 2022;8:1318–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2021.11.008

Djajadiningrat RS, van Werkhoven E, Meinhardt W, van Rhijn BWG, Bex A, van der Poel HG, et al. Penile sparing surgery for penile cancer—does it affect survival? J Urol. 2014;192:120–6.

Pandolfo SD, Biasatti A, Parnham A, Autorino R, Brouwer OR. Current role of robotic inguinal lymphadenectomy in penile cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2025;S2405-4569:00112–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2025.04.032

Sakalis VI, Campi R, Barreto L, Perdomo HG, Greco I, Zapala Ł, et al. What is the most effective management of the primary tumor in men with invasive penile cancer: a systematic review of the available treatment options and their outcomes. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2022;40:58–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2022.04.002

Zekan D, Praetzel R, Luchey A, Hajiran A. Local therapy and reconstruction in penile cancer: a review. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:2704 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16152704.

Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z

Falcone M, Plamadeala N, Cirigliano L, Preto M, Peretti F, Ferro I, et al. The outcomes of adult acquired buried penis surgical reconstruction. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14101321

Theisen KM, Fuller TW, Rusilko P. Surgical management of adult-acquired buried penis: impact on urinary and sexual quality of life outcomes. Urology. 2018;116:180–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2018.03.031

Wang J, Ni J, Xu Y, Yu W, Xu ZP, Dai YT, et al. A diamond-shaped” penoplasty technique with or without concurrent suprapubic liposuction for adult-acquired buried penis: clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction rates. Asian J Androl. 2025;27:72–75. https://doi.org/10.4103/aja202476

Barrow B, Laspro M, Brydges HT, Onuh O, Stead TS, Levine JP, et al. Technical considerations and outcomes for panniculectomy in the setting of buried penis patients: a systematic review and database analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2024;93:355–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000004025

Klein RD, Myrga JM, Redinger J, Bastacky SI, Baker EE, Quiroga-Garza GM, et al. The role of suprapubic superficial fascial system reconstruction during repair of adult-acquired buried penis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-024-04182-z

Gül M, Plamadeala N, Falcone M, Preto M, Cirigliano L, Peretti F, et al. No difference between split-thickness and full-thickness skin grafts for surgical repair in adult acquired buried penis regarding surgical and functional outcomes: a comparative retrospective analysis. Int J Impot Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-024-00832-7

Hricak H, Marotti M, Gilbert TJ, Lue TF, Wetzel LH, McAninch JW, et al. Normal penile anatomy and abnormal penile conditions: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;169:683–90. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.169.3.3186992

Kirkham A. MRI of the penis. Br J Radio. 2012;85:S86–S93. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/63301362

Neuville P, Escoffier A, Savoie PH, Fléchon A, Branger N, Rocher L, et al. French AFU cancer committee guidelines-update 2024-2026: penile cancer. Fr J Urol. 2024;34:102736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fjurol.2024.102736

Uski ACVR, Piccolo LM, Abud CP, Pedroso MHNI, Seidel Albuquerque K, Gomes NBN, et al. MRI of penile prostheses: the challenge of diagnosing postsurgical complications. Radiographics. 2022;42:159–75. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.210075

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MHG: Conceptualization; Literature review; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. AAM: Data curation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing. WGL: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing – review & editing. DR: Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This narrative review does not require ethical approval, as it is based solely on a synthesis of previously published literature and does not involve human participants, animal subjects, or patient data. Patient photographs included in this study were used with prior written informed consent obtained for academic publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gultekin, M.H., Al-Mitwalli, A., Lee, W.G. et al. The evolution of penile reconstructive techniques in urology. Int J Impot Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01141-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01141-3