Abstract

Avalanche sources describe rapid and local events that govern deformation processes in various materials. The fundamental differences between an avalanche source and its associated measured acoustic emission (AE) signal are encoded in the acoustic transfer function, which undesirably modifies the properties of the source. Consequently, information about the physical characteristics of avalanche sources is scarce and its exposure poses a great challenge. We introduce a novel experimental method based on acceleration measurements, which eliminates the effect of the transfer function and distills the avalanche source. Applying this method to deformation twinning in magnesium shows that the amplitudes and characteristic times of avalanche sources are unrelated by a clear physical law. Conversely, the amplitudes and durations of AE signals are related by a power law, which is attributed to the transfer function. Using our method, we identify and compute a new feature of avalanche sources, which is directly linked to the growth rate of the twinned volume. This feature displays a power-law distribution, implying an unpredicted behavior at dynamic criticality. Simultaneously, the characteristic times of avalanche sources possess an intrinsic upper bound, indicating a predicted limit that relates to the underlying physical process of twinning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Avalanches are impulsive and discrete events that constitute the response of an abundance of materials during a wide variety of physical processes1,2, such as plasticity in metals3,4,5 and domain switching in ferroic materials6,7,8. Knowledge gained by studying avalanches can provide essential information about the evolution of transient phenomena at various scales of length and time. For several decades, avalanche investigations have focused on universal behaviors common to all avalanches1,2,9,10,11,12,13. Recently, studies of the physical processes underlying avalanches have been gaining increasing interest14,15,16. Such studies allowed, for example, the distinction between avalanches that occur within the same material and during the same experiment, yet originate from different processes, such as dislocation movement, twinning, and martensitic transformation15. In other studies, statistical analyses of measured features of avalanches enabled extracting physical characteristics of the processes, such as an upper bound on the velocities of twin boundaries, which is attributed to a kinetic law17,18.

At the core of a physical process that gives rise to an avalanche event lies a large strain change that occurs within a microscopic region during a short time, typically at the microsecond scale, termed avalanche source14,19. Experimental investigations of physical processes that trigger avalanches necessitate measuring features directly related to the avalanche sources, which constitutes a major challenge that has yet to be accomplished. The most prevalent method for studying avalanches experimentally is the acoustic emission (AE) method, which is highly sensitive to small and rapid events, and utilizes an acoustic transducer located on one of the studied sample’s surfaces20,21,22,23. Commonly, studies focus on features of AE signals, such as the amplitudes and durations, and analyze their distributions and correlations under the implicit convention that they bear information about the physics of avalanche sources7,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

The signals measured by the AE transducer are formed by acoustic waves that travel along the sample from the location of the avalanche source. However, those waves undergo interference and reflections that distort their original properties, resulting in two limitations. First, similar avalanche sources occurring at different locations within the sample are likely to produce different AE signals. Second, the signal captured by the AE transducer is inherently different from its avalanche source14,19.

Mathematically, a measured AE signal is often modeled by a convolution between the avalanche source and a transfer function. The latter is influenced by the acoustic path between the locations of the avalanche source and the AE transducer14,31,32,33. As neither the avalanche source nor the transfer function is explicitly known, even when the source location is known, the extraction of the avalanche source based on deconvolution constitutes a double-blind problem. Some of the efforts made to extract avalanche sources have assumed specific transfer function models or that all AE signals captured during the same experiment have the same transfer function, overlooking its dependency on the location of the avalanche source14,31,32.

In this paper, we introduce a novel experimental method based on acceleration measurements that has high detection capabilities. The signals acquired by the accelerometer, comprising a frequency content different than AE signals, capture meaningful information about the temporal evolution of avalanches. Using our method, all avalanches detected during the same experiment have a constant transfer function, regardless of their location within the sample. We present an analysis method that exploits the constant transfer function and eliminates its effect while circumventing deconvolution operations. The combination of the experimental and analysis methods enables us to reveal and analyze avalanche sources based on measured acceleration signals. Particularly, the methods allow for the extraction of the amplitudes and characteristic times of avalanche sources. The latter is a key feature that has received limited attention.

We apply the developed methods to deformation twinning in magnesium single-crystals and find that the uncovered characteristic times are at the microsecond scale and are bounded by 37 μs. These times are much shorter than the durations of corresponding AE signals, which obtain values up to several milliseconds. Furthermore, a weak correspondence between the amplitudes and characteristic times of the avalanche sources indicates that these features are not related by a clear physical law. Conversely, the amplitudes and durations of measured AE signals are strongly correlated, a result that stems from the effect of the transfer functions and not the avalanche sources. Thereby, we show that the implicit convention that durations of AE signals contain information about the source durations is imprecise. Lastly, we find that the ratio between the source amplitude and its characteristic time, which is proportional to the average growth rate of the twinned volume, follows a power-law.

Results

Studied material and physical process

Twinning is a fundamental mode of plastic deformation in solid materials, particularly in hexagonal close-packed (HCP) metallic elements and alloys, such as Mg, Ti, Co, and Zr, in which twinning may surpass dislocation slip and dominates the overall plastic response34. Magnesium is a suitable test case for studying twinning in HCP alloys, as it has several twinning systems with low critical resolved shear stress (CRSS). Particularly, the \(\{10\overline{1}2\}\langle 10\overline{1}1\rangle\) system has a CRSS of 2–5 MPa35,36,37 and is favored under compression in the basal plane (as applied in this work), at which basal slip is inactive. Under these loading conditions, dislocation slip is suppressed due to a much larger Schmidt factor for twinning compared to slip35,36,37.

The twinning process evolves through three main subprocesses: the nucleation of thin needle twins, their subsequent forward growth, and their thickening through a sideways motion of the twin boundaries34,38,39,40. The nucleation and forward growth are expected to produce avalanches, as they occur at very high speeds and can even surpass the shear wave speed41. More details on the microstructural evolution of deformation twinning in the samples studied in this research are presented in the Supplementary information.

The acceleration-based experimental concept

In typical mechanical experiments, the sample is rigidly clamped to the mechanical testing machine at both ends, thereby prohibiting accelerations that are not within the sample. To enable such accelerations, we attach one end of the sample to a small mass (stage), to which the accelerometer is mounted, and connect an elastic rod to the other side of the mass. The natural frequency of the system constituting the sample, elastic rod, and mass, is fsys ∈ [3, 5] kHz. The accelerometer’s resonance frequency is facc ∈ [29, 32] kHz, and its cutoff frequency is fc = 60 kHz. The frequency range up to fc captured by the accelerometer corresponds to excitations at the microsecond scale, which are typical of avalanche events. Therefore, the accelerometer is capable of uncovering the characteristic times of avalanche sources.

An avalanche source is manifested as twinning deformation within a local microscopic volume ΔVT(t). The local avalanche source corresponds to a macroscopic plastic strain change Δεp(t), averaged over the sample’s volume Vs, through Δεp(t) = εTΔVT(t)/Vs, where εT is the twinning strain17. We choose setup parameters at which the wavelengths λ associated with the frequencies captured by the accelerometer, λ > cL/fc = 96 mm, are larger by more than an order of magnitude than the sample’s length, Ls = 8 mm, where cL is the longitudinal wave speed in magnesium. For this frequency range, the strain and stress within the sample can be considered uniform. Consequently, the acceleration measurements are determined by the macroscopic (spatially averaged) strain and stress and are not influenced by local oscillations arising from acoustic waves comprising higher frequencies. Thus, the acceleration measurements are expected to be directly related to the macroscopic plastic strain change Δεp(t) (see detailed formulation in Methods).

Evaluation of Δεp(t) via the acceleration-based method grants access to the temporal evolution and magnitude of the microscopic source ΔVT(t) at the microsecond timescale. At the same time, the location of ΔVT(t) within the sample does not influence the acceleration signal, resulting in a constant transfer function for all avalanches.

Measured signals

Six compression experiments (Methods) were carried out, during which 1648 AE signals and 743 acceleration signals were detected. Figure 1 shows three examples of acceleration signals, x(t), and their power spectral densities, which have high intensities in the ranges facc and fsys. The ratio ρ between the intensities summed over the ranges facc and fsys changes from 2.9 in Fig. 1a and 2.1 in Fig. 1b to 0.2 in Fig. 1c. Generally, a shorter duration of a source is expected to result in higher intensities at high frequencies of the corresponding acceleration signal. Therefore, ρ is a measure that facilitates the identification of a source with a short duration as part of the analysis method proposed below.

The proposed analysis method

Acceleration signals are generated by abrupt changes in the macroscopic plastic strain, which is a monotonically increasing function. Therefore, we model the source si(t) of each acceleration signal i as the sigmoid function

Here, t is the time, Ai and τi are the amplitude and characteristic time of the avalanche source, and bi and ci are constants that account for small shifts.

The measured acceleration signal xi(t) is described in the time domain by a convolution between the source function si(t) and the transfer function. This convolution becomes a simple product in the frequency domain using the Fourier transform. Thus, for each avalanche i,

where capital and lowercase letters represent respective entities in the frequency and time domains, H(ω) is the transfer function, and ω is the angular frequency. Equation (2) transfers information, frequency by frequency in the range captured by the accelerometer, from the source function to the acceleration signal through the constant transfer function. From (2), the ratio between pairs of measured acceleration signals Xi(ω) = Si(ω)H(ω) and Xj(ω) = Sj(ω)H(ω) becomes the ratio between their unknown source functions, i.e.,

If the source Sj(ω) of one measured acceleration signal Xj(ω) was known, the rest of the sources Si(ω) could have been uncovered using Eq. (3). Since all sources are unknown, we model one rapid reference source \({\hat{S}}_{R}(\omega )\) with a short enough characteristic time according to Eq. (1). We then choose a reference measured signal XR(ω) that has a large ratio ρ between high and low frequency contents, indicating it was induced by a rapid source, and consider \({\hat{S}}_{R}(\omega )\) as its source. We also ensure that XR(ω) has a large amplitude to reduce the effects of experimental errors.

Such a reference signal XR(ω) can be identified by the measured right-hand side of Eq. (3) that shows that if, at a frequency ω, the spectrum of the source si(t) has a higher intensity than that of sj(t) (i.e., ∣Si(ω)∣ > ∣Sj(ω)∣), it manifests in higher intensity in the spectrum of the acceleration signal xi(t) compared to that of xj(t) at the same ω (i.e., ∣Xi(ω)∣ > ∣Xj(ω)∣). For instance, the signal in Fig. 1b has higher intensities at facc and lower intensities at fsys than the signal in Fig. 1c (i.e., a larger ρ). Hence, the source of the former is faster than the source of the latter. This result is confirmed in the following.

Thereby, the rest of the source functions can be computed as

where a hat denotes a computed entity. By transforming Eq. (4) back into the time domain, we expose the source functions \({\hat{s}}_{i}(t)\), fit them to Eq. (1), and extract τi and Ai.

The parameters of the reference source \({\hat{s}}_{R}(t)\) in Eq. (1) (i = R for reference entities) are τR = 1 μs, AR = 1, bR = 1, and cR = 0 in arbitrary units (AU), i.e., \({\hat{s}}_{R}(t)=0.5+0.5\tanh (t/{\tau }_{R})\). We choose τR = 1 μs as this value is below the time resolution of our measurement and analysis methods, which can be estimated as \(\frac{1}{2}\frac{0.35}{{f}_{c}}\) = 2.9 μs42. Therefore, choosing a smaller τR will not affect the analysis, as shown in the following. We also show in the following that the results are insensitive to the choice of τR in the range of τR ≤ 2 μs, and choosing a substantially larger τR leads to implausible results. The choice of AR, bR, and cR means that all computed source amplitudes Ai are proportional to their corresponding sources of plastic deformation Δεp,i and to the transformed volumes ΔVT,i, yet are given in arbitrary units since the proportionality factors are unknown.

Uncovered source functions

Figure 2a, and b show the uncovered source functions \({\hat{s}}_{i}(t)\) of the acceleration signals in Fig. 1b, c, respectively, utilizing the reference signal in Fig. 1a. The curves in Fig. 2 display a clear sigmoid function with minor reminiscence of the prominent oscillations of the signals in Fig. 1. This validates that the transfer function is practically constant, and indicates that our method eliminates almost completely the influence of the transfer function embedded in the measured signals. If the influence of the transfer function was not properly diminished, the uncovered sources would not fit the sigmoid function well, and oscillations related to the transfer function would dominate the source functions. The fit based on Eq. (1) displays a good agreement with the sigmoid function and provides the extracted values of τi and Ai. Considering the different ρ values of the acceleration signals in Fig. 1b, c, indeed, the signal with the larger ρ corresponds to the faster source with the smaller τi.

Validity and robustness of the developed method

In principle, the transfer function can be influenced by changes in the sample’s dimensions, the contact between the sample and other mechanical parts, and the exact location of the sample with respect to the compression axis. Therefore, we assume the transfer function is constant only for avalanches measured during the same test. Accordingly, for each test, we choose a reference acceleration signal xR(t) from the signals captured during the same test, while ensuring that each xR(t) has a large amplitude and a high ρ value. First, we demonstrate the validity of the method and explore the effect of different choices of xR(t) and τR by analyzing a subset of 249 acceleration signals captured during one experiment, utilizing the reference signal in Fig. 1a.

Among the sources of the 249 acceleration signals, 214 exhibits a fit with adjusted R2 values exceeding 0.9, indicating a robust description of these sources by the sigmoid function in Eq. (1). Almost all of the remaining 35 sources that do not fit well to Eq. (1) correspond to signals with amplitudes that are only slightly larger than the noise level of the experimental system. Concretely, the peak amplitudes of 31 out of those 35 signals are smaller than twice the threshold.

Figure 3a shows the complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) of the 214 characteristic times τi in red crosses. To verify the small effect of the choice of xR(t) on the results, we repeat the analysis utilizing two additional reference acceleration signals that have large ρ values. The resulting CCDFs (green dots and purple circles) display very similar trends. In addition, for over 90% of the events, the largest variation in the computed τi values is smaller than 6 μs. The same choices of xR(t) have even smaller effects on the CCDFs of the source amplitudes Ai in Fig. 3b, as the three curves are almost identical. These results testify to the robustness of the proposed analysis method.

Next, we examine the effects of different choices of τR on the characteristic source times, τi. Figure 4 shows the CCDFs of τi for different values of τR, where the curve given by the red crosses is identical to that in Fig. 3a (see legend). For each curve, we report the number of uncovered sources corresponding to adjusted R2 > 0.9. Figure 4a shows the CCDFs related to τR = 0.5, 1, 2 μs in gray dots, red crosses, and green triangles, respectively. The number of sources corresponding to adjusted R2 > 0.9 related to those τR are 211, 214, and 214, respectively. The choice of τR to be 0.5, 1, or 2 μs is not expected to result in any practical difference, as those three values are below the time resolution of our method. Indeed, Fig. 4a supports this, showing that the CCDFs and number of sources corresponding to adjusted R2 > 0.9 are practically identical. This number slightly decreases to 209 for τR = 5 μs, and the main difference is that its CCDF (black circles) is narrower compared to the rest of the CCDFs in Fig. 4a.

a, b The complementary cumulative distribution functions (CCDFs) of the characteristic times of the avalanche sources, τi. The values of the reference characteristic time τR used to obtain the curves, as well as the amount of the sources corresponding to each curve whose fit to (1) adhere to adjusted R2 above 0.9, are indicated in the legend. The curve marked by the red crosses is identical to that in Fig. 3a.

Figure 4b shows the effect of the increase in τR from 1 μs (red crosses) to 10 μs (blue plus signs) and 100 μs (orange asterisks). The increase of τR from 1 μs to 10 μs leads to a similar increase in the maximal value of τi from 37 μs to 47 μs. The existence of an upper bound of τi is an important finding, but its accurate evaluation at this level is of minor importance. At the same time, the distribution corresponding to τR = 10 μs is very narrow, where 72% of the data points are located between 10 μs to 20 μs, a result that is extremely atypical of distributions of avalanche features. The choice of τR = 100 μs cuts the amount of analyzed sources that have adjusted R2 above 0.9 by 35%, indicating the poor fit in this case. Moreover, the CCDF related to τR = 100 μs presents physically contradicting results. The reference signal has a large ρ, and therefore, the majority of the sources should have τi that are larger than τR = 100 μs. Yet, all sources in Fig. 4 fulfill τi < 100 μs. To conclude, the choice of τR = 1μs is reasonable and maximizes the number of sources corresponding to adjusted R2 > 0.9.

Distributions of source features

Now, we analyze all the acceleration signals detected during six loading experiments on different samples at various stages of the deformation. Application of the proposed analysis yields a total of 659 out of 743 detected acceleration signals with adjusted R2 > 0.9 (including the 214 signals discussed above). The vast majority (80%) of the signals with lower adjusted R2 values are small-scale, having maximal amplitudes smaller than twice the threshold. Since all acceleration signals were captured during the same deformation twinning process in the same material, we combine the 659 extracted values of τi and Ai into a single dataset, which we statistically analyze.

Atypically of many avalanche studies showing features that span over several decades, the τi in Fig. 5a span over a narrow range and do not exceed 37 μs. The lower bound on τi can be attributed to the time resolution of our measurements (2.9 μs), which is determined by the cutoff frequency of the accelerometer. At the same time, neither the accelerometer nor the analysis method enforces any upper bound on τi. Therefore, the clear cutoffs indicate that the characteristic times of the source functions are naturally bounded at several tens of microseconds. The obtained τi values are in agreement with previous experimental studies on nucleation and forward growth of needle twins41, and specifically, nucleation of deformation twins in magnesium single-crystal under similar shear-resolved stress values43. Those values also match the characteristic source times of damage events in fiber-reinforced composites, although a transfer function was assumed and only a handful of source functions were obtained using deconvolution32.

a, b The complementary cumulative distribution functions (CCDFs) of the characteristic times τi and amplitudes Ai of the avalanche sources, respectively. c The CCDF of vi = Ai/τi, which is proportional to the average growth rate of twinned volume, dVT/dt. The features Ai and vi follow power-law distributions (dashed red lines) with the exponents α = 1.71 and 1.83, respectively.

The amplitudes of the sources, Ai, shown in Fig. 5b, follow a power-law for over two decades (dashed red line), where the exponent α, computed using the maximum-likelihood method44,45, is 1.71. We note that the CCDFs of the 659 τi and Ai in Fig. 5a, b behave very similarly to the CCDFs of the 214 τi and Ai in Fig. 3a, b, respectively, testifying to the robustness of our method and the repeatability of the results.

Figure 5c shows the CCDF of the ratio vi = Ai/τi. As si(t) is proportional to the plastic strain change during the avalanche, vi is proportional to the average strain rate dεp/dt based on Eq. (1). In deformation twinning, vi is also proportional to the average growth rate of the twinned volume, dVT/dt, thus providing direct information about the dynamics of this physical process. The CCDF of vi displays a broad distribution that follows a power-law over two decades with an exponent of 1.83, computed using the maximum-likelihood method44,45.

Relationships between amplitudes and durations

Figure 6a, and b depict the maximal amplitude (A) versus duration (D) of the measured AE and acceleration signals, respectively. The duration D is defined as the time difference between the first and last threshold crossings of the signal for 100 μs15,24 (see illustration in the Supplementary information). Common analyses focus on data points with large A and D, which are less affected by measurement noise, and are strongly related to each other through a power-law (although, often within a narrow range of less than a decade)7,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Our measured data display similar power-law behaviors (red lines) with exponent values of α = 1.34 for the AE data in the range 50 ≤ DAE ≤ 2000 μs and α = 2.06 for the acceleration data in the range 500 ≤ Dacc ≤ 6000 μs. These exponents are within the range of values reported in the literature, spanning from 1.14 to 2.557,24,26,27,30,46,47.

a, b The relationships between the amplitudes A and durations D of measured AE and acceleration signals (subscript acc), respectively. The red lines present power-law behaviors, where α denotes the exponent. c The relationship between the calculated amplitudes, Ai, and the calculated characteristic times, τi, of the avalanche sources. The Pearson correlation coefficients, r, of the plotted features, are indicated in the top left corners.

The plot of Ai and τi depicted in Fig. 6c displays a behavior substantially different than that in Fig. 6a, b. First, the τi in Fig. 6c are smaller by orders of magnitude than most signal durations in the analyzed range, implying that the signal durations are not representative of the source durations. Further, Fig. 6a, and b display high Pearson correlation coefficients, r, of 86% and 80%, respectively, while Fig. 6c displays a very low value of r = 8%. Indeed, the values of Ai are broadly scattered over several decades for the same values of τi.

The weak correlation and broad scattering between the amplitudes and durations of avalanche sources highlight that these avalanche features are unrelated by a clear physical law. Contrarily, the strong correlations between the amplitudes and durations of AE and acceleration signals indicate that these measured features are related by a physical law. However, this law originates from the effect of the transfer function, which is embodied in the measured signals, and not from the avalanche sources. Reasoning for these results is offered in the Supplementary information.

We further explore the relationships between features of measured AE signals and avalanche sources. To this end, we consider avalanches that generate both AE and acceleration signals. We identify these signal pairs according to their onset times, allowing an onset time difference of up to 30 μs. In contrast, the average time difference between signals detected before and after the onsets of corresponding signals in the AE-acceleration pairs is over 6 s. Out of the 659 acceleration signals discussed in the previous paragraphs, 561 were also accompanied by AE signals.

Figure 7a shows Ai, computed based on the acceleration signals, versus AAE of the AE signals induced by the same avalanches. In the range 0.08 ≤ AAE ≤ 4.5 mV, Ai increases with the increase in AAE according to \({A}_{i}\propto {({A}_{{{{\rm{AE}}}}})}^{0.94}\), and r = 28%. Generally, this almost linear trend is plausible, as strong AE signals can be expected to be induced by large avalanche sources. However, on the level of individual avalanches, the value of AAE corresponds to values of Ai scattered over a decade or more and their correlation is weak, indicating the amplitude of the avalanche source cannot be predicted from the amplitude of the AE signal.

a The relationship between the amplitudes of the sources, Ai, and the measured AE signals, AAE. b The ratio between the amplitudes of the sources and the measured AE signals, AAE/Ai, versus the characteristic times of the sources, τi. The red lines present power-law behaviors, where α denotes the exponent. The Pearson correlation coefficients, r, of the plotted features, are listed.

Figure 7b presents the ratio between the amplitudes of the AE signals and the sources, AAE/Ai, versus the characteristic source times τi, which reveals an interesting dependency. The ratio AAE/Ai is not constant for every value of τi, but rather depends on it, and particularly decreases with the increase in τi. This trend is plausible, as slower sources with larger τi are expected to generate less intensities at high frequencies, particularly at the frequency range captured by the AE sensor. Considering the range 2≤τi≤18 μs, the relation \(({A}_{{{{\rm{AE}}}}}/{A}_{i})\propto {({\tau }_{i})}^{-1.34}\) and r = − 45% hold. This dependency further shows the lack of the ability to predict Ai from AAE, as they depend on the characteristic source time τi.

Discussion

The introduced method employs measured acceleration signals to uncover avalanche sources and extract their three informative features: τi, Ai, and vi = Ai/τi. The characteristic times τi directly describe the temporal evolution of the avalanche sources. The amplitudes Ai and ratios vi are proportional to the magnitudes and average rates of the plastic strain bursts during the avalanches, respectively. These features constitute a new type of knowledge that paves the way for investigating the dynamics of various avalanche-dominated physical processes at the micrometer and microsecond scales.

The distribution of vi in magnesium is profoundly different than that of the equivalent parameter dVT/dt measured during twinning in Ni-Mn-Ga, which is bounded by a cutoff value related to a kinetic law17. This difference can be attributed to differences in the evolution mechanisms of twinning. In magnesium, twinning evolves by numerous events of twin nucleation and forward growth43 (see also the Supplementary information), while in Ni-Mn-Ga, twinning typically evolves through sidewise motion of a single twin boundary20,48. While sidewise twin boundary motion is described by well-defined kinetic laws18,49,50, twin nucleation and forward growth are far-from-equilibrium processes that often do not follow a single kinetic relation41. Indeed, power-law distributions are often explained as a consequence of dynamic criticality1,9,51,52. Roughly, this is a far-from-equilibrium state in which the dynamics of the process are unpredictable.

The power-law distributions of Ai and vi indicate that these features are scale-free. At the same time, the exponent values of these distributions (1.71 for Ai and 1.83 for vi) deviate significantly from the predictions of the mean-field theory13,53, indicating that the twinning process is not universal. There are several examples of processes that are scale-free yet material-specific, e.g., dislocation rearrangement in Au and Nb microcrystals16. Further, the narrow and bounded distribution of τi is not scale-free and has a well-defined mean, which is expected to be related to a material feature. For example, microstructural properties such as the thickness and separating distance of freshly generated twin lamella are widely scattered yet bound to a range of approximately a decade (see an example in the Supplementary information and more details in ref. 54). Future studies can aid in resolving this contradicting coexistence, as well as in revealing the origin of the inherent upper bound on τi.

In contrast to the implicit convention, we showed that the durations of AE signals do not bear information about τi. Instead, those durations can be longer than τi by several orders of magnitude, and strongly depend on the amplitudes of the AE signals, while the analogous source features τi and Ai are unrelated by a clear physical law. We explain these shortcomings as a by-product of the acoustic transfer functions, whose influence on measured AE signals calls for further exploration.

Methods

Sample

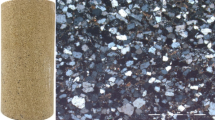

A magnesium single-crystal of 99.99% purity (Princeton Scientific Corporation) was cut into cuboid samples with the dimensions of approximately 1.5 mm × 0.6 mm × 8 mm. The large 1.5 mm × 8 mm faces of the cuboid coincide with the {0001} basal plane of the hexagonal close-packed structure. The 1.5 mm × 0.6 mm end faces coincide with \(\{10\overline{1}0\}\) prismatic planes. The samples were uniaxially compressed along the 8 mm axis of the cuboid, i.e., in a direction perpendicular to one of the prismatic planes. These loading conditions favor the formation of \(\{10\overline{1}2\}\langle 10\overline{1}1\rangle\) extension twins34,43,55. In-situ visualization of one of the 1.5 mm × 8 mm faces verified that twinning dominates the deformation of the crystal through subsequent nucleation of extension twins. Overall, we performed six loading experiments on different samples at various stages of the deformation.

Experimental details

The sample is placed between the acceleration and AE measuring apparatuses, all aligned along the loading axis. The acceleration measuring apparatus consists of the accelerometer, an aluminum stage, and an elastic rod. The AE measuring apparatus consists of the AE sensor, a mechanical spring, and an AE housing. An illustration of the experimental setup appears in the Supplementary information.

The bottom surface of the sample is in contact with the aluminum stage, to which the accelerometer (Kistler 8640A50) is attached. The stage is placed on the elastic rod, which rests on the stationary surface of the testing machine (INSTRON 5966). The top surface of the sample is in contact with the AE housing, comprised of an AE sensor (Fujicera 1045S) and a mechanical spring that ensures the sensor is subjected to a constant load. The AE housing is rigidly connected to the moving bridge of the testing machine. Compression loading is carried out at a constant bridge velocity of 0.005 mm/min, corresponding to a strain rate of 10−5 s−1. Both the acceleration and AE signals were simultaneously acquired at 10 MSa/s/ch by a Vallen AMSY-6 acquisition system. The acquisition system captures signals whose peak amplitudes exceed predetermined thresholds, which were set to 25.6 and 67.2 dB for the AE and acceleration signals, respectively (note that the AE and acceleration sensors have different amplifiers).

The values of the total moving mass, m, and the stiffness of the elastic rod, kr, are chosen to meet two essential conditions. First, the stress in the elastic rod is small enough such that no avalanches originate from it. Second, the natural frequency of the overall spring-mass system (fsys ∈ [3, 5] kHz) is high enough, such that acceleration signals decay within a few milliseconds, allowing a clear separation between consecutive avalanches.

The internal structure of the accelerometer includes piezoelectric bending beams and a small mass, leading to a frequency response that is inherently different than that typical of broadband AE sensors. It is comprised of three regions: a flat region up to the resonance frequency, a narrow resonance at approximately facc ∈ [29, 32], and a sharp decay in the gain above the resonance frequency that leads to a cutoff at approximately fc = 60 kHz. The oscillations at the frequencies fsys and facc do not influence the AE measurements due to the higher bandpass frequencies of the AE sensor (100-1500 kHz) and its filter (95-850 kHz).

Analytical description

The displacement u, velocity \(\dot{u}\), and acceleration \(\ddot{u}\) of the total moving mass, m, which includes the accelerometer and the stage, follow the equation of motion

where Fr and Fs are the forces applied by the elastic rod and the sample, respectively, c is the damping coefficient, and m = 14 g (see the free-body diagram in Supplementary Fig. 1). In the absence of avalanches, the system responds at a slow rate, such that \(\ddot{u}=0\), \(\dot{u}\) is negligible, and Fr = Fs. Due to an avalanche generated by an avalanche source, the force equilibrium is violated and the acceleration and velocity are non-zero.

In the following, we express the terms in Eq. (5) as the differences Δu, ΔFr, and ΔFs with respect to the equilibrium condition that was fulfilled right before the avalanche onset. During the short time at which \(\ddot{u}\ne 0\), the displacement applied by the mechanical testing machine is negligible, such that ΔLs = Δu and ΔLr = −Δu, where the former and latter are the length changes of the sample and elastic rod due to the displacement Δu (Supplementary Fig. 1). For the elastic rod, ΔFr = krΔLr = −krΔu = −(YrAr/L0,r)Δu, where Yr = 69 GPa, \({A}_{r}=0.25\pi {d}_{r}^{2}\), dr = 3 mm, L0,r = 25 mm are the respective Young’s modulus, cross-sectional area, diameter, and initial length of the aluminum rod having a solid circular cross-section. To express ΔFs, we express the macroscopic strain change in the sample as the sum of the elastic and plastic strain changes, respectively, i.e.,

where L0,s = 8 mm and Ys = 42 GPa are the sample’s initial length and Young’s modulus, respectively, and Δσ is the stress change with respect to the equilibrium condition right before the onset of the avalanche. By writing ΔFs = ΔσAs and substituting Δσ from Eq. (6), we obtain ΔFs = ΔσAs = ksΔLs − YsAsΔεp, where ks = YsAs/L0,s and As = 0.9 mm2. Substitution of the expressions for ΔFr and ΔFs into Eq. (5) provides

By dividing Eq. (7) by m, as well as denoting the natural frequency of the system as \({\omega }_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}=2\pi {f}_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}=\sqrt{({k}_{s}+{k}_{r})/m}\), and the damping ratio by ζ = c/(2mωsys), we have

The right-hand side of Eq. (8) represents the excitation, i.e., the source function s(t) in (1), which is only influenced by the plastic strain change Δεp.

Equation (8) describes the motion of the mass to which the accelerometer is attached. The measured acceleration signal is more complex than \(\Delta \ddot{u}\) due to the resonance vibrations of the internal components of the accelerometer. The overall transfer function of the acceleration measurements, h(t), is affected both by the parameters of the sample, elastic rod, and mass encoded in Eq. (8), as well as by the frequency response of the accelerometer. As neither Eq. (8) nor the frequency response of the accelerometer is influenced by traveling acoustic waves or by the location of the avalanche source within the sample, h(t) is constant for all avalanches measured during the same experiment.

Avalanche cascade

Many studies pointed to the possibility that a local plastic deformation event triggers another local event1,2,9,10. In this case, the time difference between those events must be smaller than the time required for acoustic waves to travel back and forth along the sample, Δtwaves = 2Ls/cL = 2.8 μs, where Ls = 8 mm is the sample’s length and cL is the longitudinal wave speed in magnesium. The time resolution of our method (2.9 μs) practically equals Δtwaves. Therefore, in our experimental setup, such events coalesce into a single avalanche with a characteristic time τi that includes both events. Thus, cascades of avalanches that trigger each other are captured in our measurements as a single event. Avalanches that appear at time differences longer than τi > Δtwaves clearly represent separate events, and are accounted as individual events in the analysis. In our measurements, most time differences between consecutive avalanches are on the order of seconds, thus their acceleration signals are distinctly separated.

Analysis details

To calculate the quotient on the right-hand side of Eq. (4), both signals must have the same number of sampled points. To meet this condition for all detected signals, we define a common length Lc = 150, 000, which is larger than the longest captured acceleration signal, and pad with zeros the entries beyond each signal’s last sampled point and up to Lc. The concatenated zeros at the end of a signal merely allow the division in Eq. (4) and do not affect the extraction of the sources that occur in the vicinity of the onset of a signal. In addition, we restrict ω = 2πf in the quotient of Eq. (4) to 0 ≤ f ≤ 60 kHz, in accordance with fc (see Fig. 1).

To extract the characteristic times τi and amplitudes Ai of the source functions, we focus on time-segments of \({\hat{s}}_{i}(t)\) that are in the vicinity of the rise of the reference source \({\hat{s}}_{R}(t)\) by considering windows of [ − w/2, w/2] centered at t = 0, which is defined as the time corresponding to the maximal slope of \({\hat{s}}_{i}(t)\). Then, we fit Eq. (1) to \({\hat{s}}_{i}(t)\) within the interval [ − w/2, w/2]. We repeat the fitting process for each computed source with varying windows w = 40, 100, 200, 300, 400, 600 μs, and choose the τi that corresponds to the w that produces the best fit (highest adjusted R2 value) while adhering to the condition w > 6τi. This condition ensures that a large enough time-segment of \({\hat{s}}_{i}(t)\) is considered in the fitting process.

Data availability

Source Data files have been deposited in Figshare under accession code56.

References

Sethna, J. P., Dahmen, K. A. & Myers, C. R. Crackling noise. Nature 410, 242–250 (2001).

Salje, E. K. & Dahmen, K. A. Crackling noise in disordered materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 233–254 (2014).

Maaß, R., Wraith, M., Uhl, J., Greer, J. R. & Dahmen, K. Slip statistics of dislocation avalanches under different loading modes. Phys. Rev. E 91, 042403 (2015).

Sparks, G. & Maaß, R. Effects of orientation and pre-deformation on velocity profiles of dislocation avalanches in gold microcrystals. Eur. Phys. J. B 92, 1–11 (2019).

Ispánovity, P. D. et al. Dislocation avalanches are like earthquakes on the micron scale. Nat. Commun. 13, 1975 (2022).

Nataf, G. et al. Domain-wall engineering and topological defects in ferroelectric and ferroelastic materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 634–648 (2020).

Salje, E., Xue, D., Ding, X., Dahmen, K. A. & Scott, J. Ferroelectric switching and scale invariant avalanches in batio3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 014415 (2019).

Durin, G. & Zapperi, S. Scaling exponents for barkhausen avalanches in polycrystalline and amorphous ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4705 (2000).

Papanikolaou, S. et al. Universality beyond power laws and the average avalanche shape. Nat. Phys. 7, 316–320 (2011).

Dahmen, K. A., Ben-Zion, Y. & Uhl, J. T. A simple analytic theory for the statistics of avalanches in sheared granular materials. Nat. Phys. 7, 554–557 (2011).

Casals, B., Nataf, G. F. & Salje, E. K. Avalanche criticality during ferroelectric/ferroelastic switching. Nat. Commun. 12, 345 (2021).

Laurson, L. et al. Evolution of the average avalanche shape with the universality class. Nat. Commun. 4, 2927 (2013).

Dahmen, K. A., Ben-Zion, Y. & Uhl, J. T. Micromechanical model for deformation in solids with universal predictions for stress-strain curves and slip avalanches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 175501 (2009).

Casals, B., Dahmen, K. A., Gou, B., Rooke, S. & Salje, E. K. The duration-energy-size enigma for acoustic emission. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Chen, Y., Gou, B., Ding, X., Sun, J. & Salje, E. K. Real-time monitoring dislocations, martensitic transformations and detwinning in stainless steel: Statistical analysis and machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 92, 31–39 (2021).

Sparks, G. & Maaß, R. Shapes and velocity relaxation of dislocation avalanches in au and nb microcrystals. Acta Mater. 152, 86–95 (2018).

Bronstein, E. et al. Tracking twin boundary jerky motion at nanometer and microsecond scales. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2106573 (2021).

Faran, E. & Shilo, D. The kinetic relation for twin wall motion in nimnga—part 2. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 61, 726–741 (2013).

Eitzen, D. & Wadley, H. Acoustic emission: establishing the fundamentals. J. Res. Natl Bur. Stand. 89, 75 (1984).

Zreihan, N., Faran, E., Vives, E., Planes, A. & Shilo, D. Relations between stress drops and acoustic emission measured during mechanical loading. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 043603 (2019).

Baró, J. et al. Statistical similarity between the compression of a porous material and earthquakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 088702 (2013).

Bronstein, E. et al. Enhancing the detection capabilities of nano-avalanches via data-driven classification of acoustic emission signals. Phys. Rev. E 108, 045001 (2023).

Nataf, G. F. et al. Predicting failure: acoustic emission of berlinite under compression. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 275401 (2014).

Chen, Y., Ding, X., Fang, D., Sun, J. & Salje, E. K. Acoustic emission from porous collapse and moving dislocations in granular mg-ho alloys under compression and tension. Sci. Rep. 9, 1330 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Acoustic emission spectra and statistics of dislocation movements in fe40mn40co10cr10 high entropy alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 080901 (2022).

Shao, G. et al. Acoustic emission study on avalanche dynamics of ferroelectric switching in lead zirconate titanate ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 224102 (2022).

Eckstein, J. T., Carpenter, M. A. & Salje, E. K. Ubiquity of avalanches: Crackling noise in kidney stones and porous materials. APL Mater. 11, 031112 (2023).

Lebedkina, T., Bougherira, Y., Entemeyer, D., Lebyodkin, M. & Shashkov, I. Crossover in the scale-free statistics of acoustic emission associated with the portevin-le chatelier instability. Scr. Mater. 148, 47–50 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Avalanches during ferroelectric and ferroelastic switching in barium titanate ceramics. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 124413 (2022).

Chen, Y., Wang, Q., Ding, X., Sun, J. & Salje, E. K. Avalanches and mixing behavior of porous 316l stainless steel under tension. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 111901 (2020).

Agletdinov, E., Merson, D. & Vinogradov, A. A new method of low amplitude signal detection and its application in acoustic emission. Appl. Sci. 10, 73 (2019).

Zheng, G., Buckley, M., Kister, G. & Fernando, G. Blind deconvolution of acoustic emission signals for damage identification in composites. AIAA J. 39, 1198–1205 (2001).

Kocur, G. K. Deconvolution of acoustic emissions for source localization using time reverse modeling. J. Sound Vib. 387, 66–78 (2017).

Christian, J. W. & Mahajan, S. Deformation twinning. Prog. Mater. Sci. 39, 1–157 (1995).

Mordike, B. & Ebert, T. Magnesium: properties—applications—potential. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 302, 37–45 (2001).

Dieringa, H., StJohn, D., Pérez Prado, M. T. & Kainer, K. U. Latest developments in the field of magnesium alloys and their applications. Front. Mater. 8, 726297 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. A review on magnesium alloys for biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 953344 (2022).

Beyerlein, I. J., Zhang, X. & Misra, A. Growth twins and deformation twins in metals. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 329–363 (2014).

Boyko, V., Garber, R. & Kossevich, A. Reversible crystal plasticity (American Institute of Physics, New York, 1997).

Lubenets, S., Startsev, V. & Fomenko, L. Dynamics of twinning in metals and alloys. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 92, 11–55 (1985).

Faran, E. & Shilo, D. Twin motion faster than the speed of sound. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 155501 (2010).

Pomponi, E., Vinogradov, A. & Danyuk, A. Wavelet based approach to signal activity detection and phase picking: Application to acoustic emission. Signal Process. 115, 110–119 (2015).

Kannan, V., Hazeli, K. & Ramesh, K. The mechanics of dynamic twinning in single crystal magnesium. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 120, 154–178 (2018).

Clauset, A., Shalizi, C. R. & Newman, M. E. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Rev. 51, 661–703 (2009).

Salje, E. K., Planes, A. & Vives, E. Analysis of crackling noise using the maximum-likelihood method: Power-law mixing and exponential damping. Phys. Rev. E 96, 042122 (2017).

Daróczi, L. et al. Change of acoustic emission characteristics during temperature induced transition from twinning to dislocation slip under compression in polycrystalline sn. Materials 15, 224 (2021).

Kamel, S. M., Samy, N. M., Tóth, L. Z., Daróczi, L. & Beke, D. L. Denouement of the energy-amplitude and size-amplitude enigma for acoustic-emission investigations of materials. Materials 15, 4556 (2022).

Straka, L., Lanska, N., Ullakko, K. & Sozinov, A. Twin microstructure dependent mechanical response in ni–mn–ga single crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 131903 (2010).

Hayashi, M. Kinetics of domain wall motion in ferroelectric switching. ii. application to barium titanate. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 34, 1240–1244 (1973).

Abeyaratne, R. & Knowles, J. K. Evolution of phase transitions: a continuum theory (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006).

Planes, A., Mañosa, L. & Vives, E. Acoustic emission in martensitic transformations. J. Alloy. Compd. 577, S699–S704 (2013).

Ispánovity, P. D., Groma, I., Györgyi, G., Szabó, P. & Hoffelner, W. Criticality of relaxation in dislocation systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 085506 (2011).

LeBlanc, M., Angheluta, L., Dahmen, K. & Goldenfeld, N. Universal fluctuations and extreme statistics of avalanches near the depinning transition. Phys. Rev. E 87, 022126 (2013).

Shilo, D. & Faran, E. Rate-independent mechanism of deformation twinning in single crystal magnesium. Acta Mater. 278, 120223 (2024).

Prasad, K. E., Rajesh, K. & Ramamurty, U. Micropillar and macropillar compression responses of magnesium single crystals oriented for single slip or extension twinning. Acta Mater. 65, 316–325 (2014).

Bronstein, E., Faran, E., Talmon, R. & Shilo, D. Uncovering avalanche sources via acceleration measurements. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26485030 (2024).

Acknowledgements

E.B., E.F., and D.S. wish to thank the Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 1600/22) for partial support of this study. E.B. is grateful to the Azrieli Foundation for the award of an Azrieli Fellowship. R.T. acknowledges the support of the Schmidt Career Advancement Chair in AI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B.: Conceived and designed the experiments, Performed the experiments, Conceived and designed the analysis method, Analyzed the data, Wrote the paper; E.F.: Conceived and designed the experiments, Performed the experiments, Wrote the paper; R.T.: Conceived and designed the analysis method, Analyzed the data, Wrote the paper; D.S.: Conceived and designed the experiments, Performed the experiments, Conceived and designed the analysis method, Analyzed the data, Wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Peter Ispanovity, Guillaume Nataf, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bronstein, E., Faran, E., Talmon, R. et al. Uncovering avalanche sources via acceleration measurements. Nat Commun 15, 7474 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51622-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51622-0