Abstract

Forests harbor extensive biodiversity and act as a strong global carbon and nitrogen sink. Although enhancing tree diversity has been shown to mitigate climate change by sequestering more carbon and nitrogen in biomass and soils in manipulative experiments, it is still unknown how varying environmental gradients, such as gradients in resource availability, mediate the effects of tree diversity on carbon and nitrogen accrual in natural forests. Here, we use Canada’s National Forest Inventory data to explore how the relationships between tree diversity and the accumulation of carbon and nitrogen in tree biomass and soils vary with resource availability and environmental stressors in natural forests. We find that the positive relationship between tree functional diversity (rather than species richness) and the accumulation of carbon in tree biomass strengthens with increasing light and soil nutrient availability. Moreover, the positive relationship between tree functional diversity and the accumulation of carbon and nitrogen in both organic and mineral soil horizons is more pronounced at sites with greater water and nutrient availabilities. Our results highlight that conserving and promoting functionally diverse forests in resource-rich environments could play a greater role than in resource-poor environments in enhancing carbon and nitrogen sequestration in Canada’s forests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forests play a pivotal role in the exchange of carbon (C) between the biosphere and atmosphere, sequestering about 30% of annual global anthropogenic CO2 emissions1. In addition, nitrogen (N) availability in forest soils is critical in determining plant growth and associated C sequestration2. Consequently, enhancing the capacity of forests to sequester more C in plants and soils while retaining greater soil N to support C sequestration is an important nature-based climate solution to help limit global warming to 1.5 °C by the end of this century3. Recent studies have emphasized that increasing tree diversity is a powerful nature-based strategy for enhancing C sequestration4, as forest productivity and soil C and N accumulation are often higher in species-rich tree communities over monocultures5,6,7,8. However, available evidence, especially for plant diversity effects on soil C and N accumulation, primarily comes from designed biodiversity manipulation experiments conducted in homogeneous conditions6,8. It remains unclear how positive biodiversity-ecosystem functioning (BEF) relationships vary with resource availability (e.g., light, water, and soil nutrients) and background environmental conditions in heterogeneous natural forests9,10,11. Understanding the role of resource availability and other background environmental factors in shaping BEF relationships is necessary to improve predictive BEF models and inform forest management and conservation.

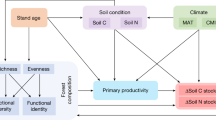

The role of ‘facilitation’ and ‘resource (niche) partitioning’—two major mechanisms that contribute to efficient ecosystem functioning in species-rich plant communities— might shift with changes in resource availability and non-resource-related environmental stressors (hereafter referred to as ‘non-resource stressors’)12 (Fig. 1). Specifically, facilitation (considered a form of complementarity) occurs when some species in a plant assemblage enhance resource availability and/or modify the environment in such a way that it alleviates stress and enhances productivity of other species, and thus for the entire plant community12. Based on the ‘stress-gradient hypothesis,’ the role of facilitation may become stronger as environmental stresses increase through stress amelioration13 (Fig. 1). For example, based on the Swiss National Forest Inventory data, both spruce and fir have been found to be more productive in mixtures than in monocultures at sites experiencing high acidity stress, rather than those with optimum soil pH14. However, the generality of the stress-gradient hypothesis is contentious, particularly in its applicability to gradients in resource availability, as it ignores the high dependence of facilitation on the presence of resource-enrichment facilitative species10,15. In the absence of such species, resource competition would come to dominate plant-plant interactions when resources are more limited15,16. Alternatively, the resource partitioning effect (another form of complementarity) occurs when coexisting species in a plant assemblage employ distinct strategies to harvest resources by partitioning their acquisition in space, time, or chemical form12. Compared with facilitation, resource partitioning would consistently work to enhance ecosystem functioning12, and might show a hump-shaped pattern as resource availability increases. In extremely resource-limited environments, the role of resource partitioning is less pronounced due to the scarcity of resources available for partitioning. As resource limitations become moderate, resource partitioning likely plays a more significant role due to the greater availability of resources for diverse plant communities to use in resource partitioning10,15. However, in environments rich in resources, plant communities are less dependent on resource partitioning to increase productivity, as resources themselves are no longer a limiting factor12. In natural high-latitude forests, typically constrained by multiple resources, we expect that positive BEF relationships would be strengthened with increasing resource availability (Fig. 1).

Manipulative experiments have revealed that the positive effects of plant diversity on productivity were stronger under resource enrichment, such as the addition of water and N, and higher levels of temperature, light, and CO2 availability17,18,19,20; however, these experiments are constrained by the size of the experimental unit and scope, thus limiting the inference space for projecting large-scale patterns. Recently, large-scale observational studies of natural forests have been employed to explore the relationship between tree diversity and productivity along climate gradients and equivocal results have been reported21,22,23,24. Some studies are aligned with the stress gradient hypothesis, showing a more pronounced positive association between tree diversity and productivity in drier than in more humid regions21,22, while others reveal increasing positive relationships with rising water availability23,24. Moreover, relationships between tree diversity and C and N accumulation on a large scale have rarely been examined within the framework of both resource availability and non-resource stress gradients, especially for soil C and N accumulation. Previous large-scale observational studies generally evaluated relationships between tree diversity and soil C and N stocks at one point in time, possibly overlooking the enduring influence of historical plant compositions, which can shape soil C and N storage for centuries or even millennia25. Compared with soil C and N stocks that reflect long-term net accumulation over centuries, soil C and N accumulation during recent decades should better reflect the effects of recent tree diversity and provide a standardized timeframe for comparison7. Finally, although temperature is not traditionally considered a resource (as it is not consumable), it often serves as a surrogate for chemical energy availability in addition to light since higher temperatures are generally more favorable for productivity and soil C and N cycling in high-latitude forests as long as there is sufficient water available as well26,27,28.

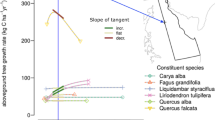

In this study, we investigate how resource availability and non-resource stressors influence the relationship between tree diversity and the accumulation of C and N in trees and forest soils (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). We analyze the decadal accumulation of C in tree biomass, and C and N in the organic and mineral soil horizons as a function of tree diversity and their interaction with light, water and N availability, air temperature, and non-resource stressors (i.e., heatwaves and low soil pH) gradients while controlling for the influence of forest stand age and tree functional identity. Diversity in functional traits (hereafter referred to as ‘functional diversity’, FDis) within each inventory plot tree community is used to represent tree diversity, as it better captures resource partitioning effects29. In this paper, we specifically hypothesize that the positive relationship between tree functional diversity and the accumulation of C in tree biomass and C and N in the soil will be stronger in resource (light, water, and N)-rich environments and areas experiencing higher heatwave or acidity stress, due to enhanced resource partitioning and facilitation, respectively. When assessing how relationships between tree functional diversity and changes in C and N accumulation vary with resource availability, we simultaneously consider three resource factors—light (mean annual solar radiation, hereafter solar radiation), water (mean annual climate moisture index, hereafter CMI), and nitrogen (decadal cumulative N deposition rate, hereafter N deposition) availability—along with their interactions with FDis. In addition, soil C/N ratios in both the organic and mineral soil horizons are used as a surrogate of site nutrient status to replace N deposition in the full models. When assessing how the relationship between tree functional diversity and changes in C and N accumulation vary with non-resource stress variables, we conduct separate analyses for mean annual heatwave intensity (hereafter HI) and soil pH, given the independence of their effects on soil C and N stocks and the lack of soil pH data from some sites. Given the high geographical intercorrelation between solar radiation and MAT (R2 = 0.34, Supplementary Fig. 4), we take a stepwise approach to disentangling their impacts on C and N accumulation (see details in Methods). To prevent overfitting, the most parsimonious models are selected based on the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Fig. 2). These analyses are based on data from the first (2000–2006) and second (2008–2017) census of the Canadian National Forest Inventory (NFI) permanent sample plot network, which offers a broad representation of Canada’s temperate and boreal forests.

Results

We found that interactions between tree functional diversity and the environmental drivers affected C accumulation in trees and the accumulation of both C and N in the soil (Supplementary Tables 1–4). Solar radiation and soil C/N were the main resource variables that modulated relationships between FDis and tree C accumulation in the most parsimonious (with the lowest AIC) models. In contrast, CMI, N deposition, and soil C/N were the main variables that modulated C and N accumulation in organic and mineral soil horizons (Fig. 2). The HI was included as the main non-resource stress explanatory variable for all C and N accumulation variables except the decadal soil C change in the mineral horizon. In comparison, soil pH was only retained as the main stress predictor for C accumulation in tree biomass in the most parsimonious model (Fig. 2).

Resource availability and tree diversity affect tree biomass C accumulation

With respect to trees, solar radiation was positively related to tree biomass C accumulation in the most parsimonious model (F = 22.45, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, P = 0.000003) (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 3a). Tree biomass C accumulation was also positively associated with MAT (F = 32.93, df = 1, P = 1.6 × 10−8) (Supplementary Fig. 5a). However, we found that solar radiation was still positively correlated with C accumulation in tree biomass when modeling the residuals from the regression of tree biomass C accumulation on MAT as a function of solar radiation and its interaction with FDis (F = 6.64, df = 1, P = 0.010, Supplementary Fig. 5b), indicating that C accumulation in tree biomass significantly increases with solar radiation, even after accounting for the effects of MAT. In addition to solar radiation, C accumulation in tree biomass was inversely correlated with the organic horizon soil C/N (F = 14.91, df = 1, P = 0.0001), and pH (F = 6.47, df = 1, P = 0.012) (Fig. 3c, e).

a, b Solar-dependent responses for residual tree biomass C accumulation (as indicated by the Δ symbol) after removing MAT effect; c, d organic horizon soil C/N-dependent responses; e, f soil pH-dependent responses. The black line and grey shaded areas in panels a, c, and e represent the fitted regression and its bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Colored lines in panels b, d, and f represent the Solar-, soil C/N-, and pH-specific responses, with their bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals shaded in the corresponding color. Solar, soil C/N, and soil pH were analyzed as continuous variables but illustrated here based on the meaningful three levels of breakpoints (mean, mean plus, and minus standard deviation (SD)). The significance (P) is reported for each term tested, with P values calculated using a one-sided F test. Solar: decadal average of annual solar radiation (for each plot), df: degrees of freedom.

The accumulation of C in tree biomass was positively correlated with FDis, and this relationship was dependent on environmental variables (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 3). In line with our hypothesis, the increase in tree biomass C accumulation with FDis was more pronounced at sites with high solar radiation and low soil C/N (i.e., relatively N-rich soils), compared to sites with low solar radiation (F = 7.54, df = 1, P = 0.006, Fig. 3b) and high soil C/N (i.e., relatively N-poor soils) in the organic horizon (F = 8.30, df = 1, P = 0.004, Fig. 3d). In addition, the positive association between tree FDis and the C accumulation in tree biomass marginally shifted from neutral at sites with optimum soil pH (pH = 7.0) to positive at sites with high acidity (pH = 4) (F = 2.88, df = 1, P = 0.091, Fig. 3f).

Resource availability and tree diversity affect soil C and N accumulation

We found that C accumulation in the organic soil horizon did not increase with tree FDis (F = 2.99, df = 1, P = 0.085), but that the accumulation of C in the mineral soil horizon was positively related to tree FDis (F = 6.69, df = 1, P = 0.010) (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). However, the associations between FDis and the accumulation in soil C were conditional on at least one of several environmental variables (CMI, N deposition, or HI) (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). The association between FDis and C accumulation in the organic horizon shifted from negative at low-CMI sites to positive at high-CMI sites (F = 13.20, df = 1, P = 0.0003, Fig. 4a). In addition, the association between FDis and C accumulation in the organic horizon marginally shifted from neutral at sites with low soil C/N to positive at sites with high soil C/N in the organic horizon (F = 3.76, df = 1, P = 0.053, Fig. 4b). In addition, the C accumulation in the organic horizon was positively correlated with FDis at sites with low HI, but negatively correlated with FDis at sites with high HI (F = 8.52, df = 1, P = 0.004, Fig. 4c). Moreover, the positive association between FDis and C accumulation in the mineral horizon was (significantly or marginally significantly) more pronounced at N-rich sites that were characterized by high N deposition (F = 9.29, df = 1, P = 0.003) and low soil C/N in both the organic and mineral horizons (F = 4.02, df = 1, P = 0.046 and F = 2.80, df = 1, P = 0.096, respectively) (Fig. 5).

a CMI-dependent responses; b organic horizon soil C/N-dependent responses; c HI-dependent responses. Colored lines represent the CMI-, soil C/N-, and HI-specific responses, with their bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals shaded in the corresponding color. CMI, soil C/N, and HI were analyzed as continuous variables but illustrated here based on the meaningful three levels of breakpoints (mean, mean plus, and minus standard deviation (SD)). The significance (P) is reported for each term tested, with P values calculated using a one-sided F test. CMI: decadal average of annual climate moisture index (for each plot), HI: decadal average of annual heatwave intensity (for each plot). df: degrees of freedom.

a N deposition-dependent responses; b organic horizon soil C/N-dependent responses; c mineral horizon soil C/N-dependent responses. Colored lines represent the N deposition- and soil C/N-specific responses, with their bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals shaded in the corresponding color. N deposition and soil C/N were analyzed as continuous variables but illustrated here based on the meaningful three levels of breakpoints (mean, mean plus and minus standard deviation (SD)). The significance (P) is reported for each term tested, with P values calculated using a one-sided F test. ND: decadal cumulative of N deposition (for each plot), df: degrees of freedom.

The N accumulation in the organic soil horizon did not increase with tree FDis (F = 0.99, df = 1, P = 0.321), but that in the mineral soil horizon was positively related to tree FDis (F = 11.66, df = 1, P = 0.0008) (Supplementary Table 4). Similar to C accumulation, the N accumulation in the organic and mineral horizon were, respectively, positively correlated with FDis at sites with low HI (F = 7.25, df = 1, P = 0.007) and high N deposition (F = 10.28, df = 1, P = 0.002), rather than sites with high HI and low N deposition (Fig. 6a, b). In contrast, the relationship between FDis and N accumulation in the mineral soil horizon marginally shifted from neutral at sites with low HI to positive at sites with high HI (F = 3.85, df = 1, P = 0.051) (Fig. 6c).

a CMI-dependent N accumulation in the organic horizon; b N deposition-dependent N accumulation in the mineral horizon; c HI-dependent N accumulation in the mineral horizon. Colored lines represent the CMI, N deposition, and HI-specific responses, with their bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals shaded in the corresponding color. CMI, N deposition, and HI were analyzed as continuous variables but were illustrated here based on meaningful three levels of breakpoints (mean, mean plus and minus standard deviation (SD)). The significance (P) is reported for each term tested, with P values calculated using a one-sided F test. CMI: decadal average of annual climate moisture index (for each plot), ND: decadal cumulative N deposition (for each plot), HI: decadal average of annual heatwave intensity (for each plot), df: degrees of freedom.

In addition, we also tested the effects of species richness and evenness on C and N accumulation by replacing the terms of FDis in the most parsimonious model with species richness and evenness. Our results revealed significant interactive effects of species evenness and several environmental factors (solar radiation, CMI, N deposition, and HI) on C and N accumulation in tree biomass and soils, largely mirroring those of significant interactive effects of functional diversity and environmental factors (Supplementary Tables 1–5). In contrast, the interactive effects of species richness with environmental variables on C and N accumulation in trees and soils were generally non-significant (Supplementary Table 6), suggesting that equitable distribution of functional traits, instead of the number of species, drives changes in C and N sequestration in natural forests across resource and non-resource gradients.

Discussion

This study shows that the relationship between FDis and the decadal accumulation of C and N in tree biomass and forest soils is dependent on resource availability and non-resource stress variables, underscoring the importance of considering the environmental context in studying biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relationships. Specifically, we found that the positive association between tree functional diversity and C accumulation in tree biomass was more pronounced in solar radiation-, and nutrient-rich environments. Additionally, the positive relationship between functional diversity and C and N accumulation in the organic soil horizon was more pronounced in high-water and low-heatwave conditions, while in mineral soil horizons, these relationships were stronger in nutrient-rich and high-heatwave environments. Our results validate the results from small-scale experimental studies that manipulate plant diversity, resource availability, and environmental conditions17,18.

The increased C accumulation in tree biomass with increasing solar radiation conditions is consistent with previous studies26,30, suggesting that the productivity of Canada’s forests is a function of temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation. Given that solar radiation was significantly correlated with MAT in cold forests (MAT < 3 °C), but not in warmer forests (MAT ≥ 3 °C) (Supplementary Fig. 4), the lower C accumulation in tree biomass that we observed in regions with low solar radiation may result not only from limited energy for photosynthesis but also from lower MAT31. Thus, the positive relationship between tree C accumulation and solar radiation observed here should be interpreted cautiously, especially in cold regions. Regarding non-resource stress factors, prolonged extreme warmth would result in a decline of net photosynthesis, as indicated by the lower rate of tree C accumulation observed under greater heatwave intensity32. Despite the expected aluminum toxicity in low acidic soils (typically seen in soils with a calcium/aluminum ratio <1), we observed greater tree C accumulation in highly acidic soils (pH around 2.8) than in optimum soils (pH around 7.0), which collaborates with results from a US national forest inventory-based study33. The absence of calcium deficiency in boreal soils, unlike tropical soils may partly explain why trees in highly acidic soils still exhibit robust growth34. In addition, decreasing soil pH could enhance the availability of some soil nutrients (e.g., copper and iron), and promote the establishment of ectomycorrhizal fungal-associated tree species, resulting in an increase in forest productivity33,35.

Importantly, our results show that the positive relationship between tree functional diversity and C accumulation in tree biomass appears to strengthen under higher solar radiation and N availability (characterized by low C/N), indicating that the resource partitioning effect in functionally diverse forests can benefit from increased resource availability17,19. At sites with relatively higher solar radiation and available N, the greater light and N capture capacity of more diverse forests5,36 would use the light and N more completely, resulting in increased production of tree biomass19.

Our results also showed that functionally diverse tree communities had greater C accumulation in the organic horizon in humid environments. Enhanced tree diversity may lead to increased litter input37, thereby boosting C accumulation in the organic horizon at wetter sites, where organic matter decomposes more slowly under wetter conditions38. In comparison, less diverse tree communities had greater C accumulation in the organic horizon in drier environments. Given that plant functional diversity could also increase decomposition rates in the organic horizon37, our results suggest that in more humid environments, tree diversity might enhance productivity more than it accelerates decomposition and mineralization processes, whereas, in drier environments, tree diversity potentially enhances productivity less than it accelerates decomposition and mineralization processes, similar to findings in grasslands39. The wetter condition that slows organic matter decomposition discussed earlier may also counteract the enhancement of functional diversity on organic matter decomposition. Moreover, the more pronounced positive associations between tree functional diversity and C and N accumulation in the mineral horizon at sites with relatively high N availability indicate that increased soil N availability benefits resource partitioning in high- than low-diversity tree communities, enhancing root productivity and rhizodeposition40,41, thereby resulting in higher C and N accumulation in the mineral horizon.

In contrast with our hypothesis, the positive relationship between tree functional diversity and C accumulation in the organic horizon was marginally stronger at low N sites characterized by organic matter with high C/N ratios. It is possible that high C/N ratios in the organic horizon slow down the decomposition rate and, in so doing, accumulate the C from enhanced litter input in diverse tree communities42. Given the antagonistic effects between water availability and nitrogen enrichment on the impact of tree functional diversity on organic horizon C accumulation, more studies are needed to examine the interaction effect of precipitation and N addition in regulating the relationship between tree diversity effects and soil C storage. Our results collectively suggest that a reduction in tree functional diversity might lead to greater C and N loss in forest biomass and mineral soils that are subject to increased nitrogen input in the future.

Regarding non-resource stress factors, we found a more pronounced positive relationship between functional diversity and tree C accumulation in highly acidic soils (though only marginally significant), while N accumulation in the mineral horizon increased with tree functional diversity in environments with high heatwave stress, partly validating the stress-gradient hypothesis12. However, functionally diverse tree communities had greater C and N accumulation in the organic horizon in environments with low heatwave stress, while less diverse tree communities (e.g., monocultures) showed greater C and N accumulation in the organic horizon under strong and prolonged heatwave stresses, probably because of the enhanced decomposition rate of the organic horizon under high heatwave stress43. In addition to being a stressor, heatwave events can provide energy to enhance temperature-dependent ecosystem processes43, such as the decomposition of organic matter in the organic horizon, thus attenuating the increased litter input associated with higher tree functional diversity. We note that functional diversity in Canada’s predominantly boreal and hemi-boreal forests, with a range of 0–2.4 and an average of 0.7, is much lower than those in tropical and subtropical forests44. Therefore, extrapolating our findings to ecosystems with higher functional diversity should be approached with caution. Since functional redundancy is also higher in tropical and subtropical forests44, C sequestration in tree biomass might not change with functional diversity in ecosystems with a higher functional diversity45. Moreover, our models’ predictive powers (R2) are relatively low, which might be partly attributable to the relatively small sample sizes and the wide range of variability in non-measured climate, soil, disturbance regime and evolutionary history in conducting the measurements46. However, low predictive power at the individual sample level does not necessarily indicate the absence of significant relationships.

In conclusion, we show that relationships between tree diversity and ecosystem functioning are not constant across environmental gradients. Carbon accumulation in tree biomass might be substantially increased by promoting tree functional diversity in areas with abundant light and nutrients. Similarly, enhancing tree functional diversity in regions with high water and nutrient availabilities might significantly boost soil C and N accumulation compared with regions with low water and nutrient availabilities. Moreover, we also highlight the stronger positive association (although only marginally significant) between tree functional diversity and tree C accumulation at sites with greater acidity stress, partly supporting the stress-gradient hypothesis. Given that N deposition might also result in soil acidification at the global scale in the future47, our results suggest that reductions in tree diversity may reduce the capacity of forests to store C under N deposition and soil acidification. Therefore, efforts to promote tree diversity to enhance C sequestration and N retention for mitigating climate change and improving ecosystem sustainability must take into account the overarching role of local environmental conditions.

Methods

Study area and available data

We used plot-level data from the Canadian National Forest Inventory (NFI) database48 to determine how tree diversity and environmental gradients interactively affect C and N accumulation in trees and soils. The NFI database encompasses a network of permanent ground plots covering much of Canada’s forests across boreal and temperate biomes. The permanent plots were established and monitored by Canadian provincial authorities between 2000 and 2006 (first measurement) and subsequently re-measured between 2008 and 2017 (second measurement) following the same standard ground sampling guidelines established by the Canadian Forest Inventory Committee49. For inclusion in our analysis, we selected only those plots situated in forest stands that were unmanaged and had not been relocated at the time of sampling, with two measurements conducted and complete data coverage for forest canopy composition, stand age, tree C accumulation, soil C and N stocks. After excluding missing values for each horizon, 513 plots for canopy trees (Supplementary Fig. 1), 360 plots for organic soil horizon samples (Supplementary Fig. 2) and 244 plots for 0–15 cm mineral soil horizon samples (Supplementary Fig. 3) that span from 44°00’–64°24’ N to 53°24’–128°36’ W were included in the statistical analyses (Supplementary Table 7).

In each plot, which comprises several sub-plots, a ‘Large Tree Plot’ was established with a radius of 11.28 m and an area of 400 m2 (0.04 ha). Within this Large Tree Plot, all canopy trees (tree stems ≥ 9.0 cm in diameter at breast height) were systematically numbered, tagged, identified for species, and measured for both height and DBH. The aboveground biomass of individual trees was estimated using published Canadian national species-specific DBH-based tree aboveground biomass allometric equations50. We then converted the aboveground biomass to the aboveground C stock of each tree by multiplying aboveground biomass with biome-level C concentrations of woody biomass based on Martin, Doraisami, and Thomas51. The decadal C accumulation in tree biomass due to tree growth (hereafter tree C accumulation) was calculated as the C increment by the growth of surviving trees and ingrowth by recruited trees between the two censuses52. In addition to the ‘Large Tree Plot’, four 1 m2 “Microplots” were established outside of the large tree plot (but within a 15 m radius of the Large Tree Plot center). From each of these microplots, an organic horizon soil sample was collected that comprised the litter, fabric, and humus layers (over 17% organic C by mass) using 20 × 20 cm (inside dimensions) aluminum sampling frames53. Furthermore, seven mineral soil horizon samples (less than 17% organic C) were collected from each NFI microplot at fixed depths (0–15 cm) using a 10-cm diameter auger. The collected organic and mineral soil samples were dried at 70 °C in an oven and were subsequently sieved using 8 and 2 mm screens to eliminate gravel and roots, respectively. Soil C content, N content, pH, and bulk density were measured for each soil sample following standard protocols49. Soil C and N stocks were calculated by multiplying soil C and N content by the soil bulk density of each soil horizon54. Then decadal changes in soil C and N stocks in the organic (ΔSoil CO stock and ΔSoil NO stock, kg m−2 decade−1) and mineral horizons (ΔSoil CM stock and ΔSoil NM stock, kg m−2 decade−1) were calculated as the difference in soil C and N stock between the two censuses divided by the census length in decades. We found that soil pH in the mineral horizon did not change with soil C/N ratios (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Tree functional diversity and functional identity

To calculate functional diversity and identity, we employed five key functional traits that are linked to tree growth and resource acquisition abilities: ‘leaf N content per leaf dry mass’ (Nmass, mg g−1), ‘leaf phosphorus content per leaf dry mass’ (Pmass, mg g−1), ‘specific leaf area’ (SLA, mm2 mg−1; i.e., leaf area per leaf dry mass), ‘wood density’ (WD, g cm−3), and maximum height (MH, m)23,55,56,57. We acquired the mean trait values for Nmass, Pmass, SLA, WD, and MH by aggregating all available measurements for each tree species from the TRY Plant Trait Database58. Functional dispersion was used as an index of tree functional diversity, which considers species relative abundances59. Functional dispersion was calculated as the average distance of individual tree species to the centroid in the multidimensional trait space of all tree species weighted by the relative basal area59.

The stand age for each permanent sample plot was determined according to the date of the last stand-replacing fire or by coring three dominant/co-dominant trees in each plot. The stand age was represented by the mean stand age between the first and second NFI measurements.

The community-weighted means (CWMs) of the five traits, with weights reflecting basal area, were utilized to estimate the functional identity of the tree community using principal component analysis (PCA)60,61,62. Specifically, the first (CWMPC1, explaining 47% of the variation) and the second axes (CWMPC2, explaining 23% of the variation) of the PCA were used as proxies of functional identity. The CWMPC1 represents traits associated with resource acquisitive abilities55,63,64, and is strongly related to CWMSLA, CWMNmass, and CWMPmass. The CWMPC2 is related negatively to maximum height (CWMMH) and positively to wood density (CWMWD) (Supplementary Fig. 7). An assemblage of species characterized by fast growth rates (higher CWMPC1) and large biomass stock (lower CWMPC2) is expected to increase tree productivity and N retention and, therefore, soil C and N pools via increased tree litter input65,66. On the other hand, traits representing low resource acquisition abilities, such as low leaf N and P concentrations, specific leaf area, and high wood density, are also expected to contribute to soil C and N accumulation through the input of low-quality (recalcitrant) tree litter with slow decomposition rates29,67. The calculation of FDis and CWM was conducted using the FD package in R59. In order to account for the variation in tree diversity during these measurements, we used the mean values of FDis and CWM across the two censuses as proxies for tree diversity and identity23. The FDis slightly increased with solar radiation (F = 4.33, df = 1, P = 0.038) and N deposition (F = 6.35, df = 1, P = 0.012), but did not change with water availability (F = 0.42, df = 1, P = 0.516) (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Local climate and soil condition

We used decadal mean annual solar radiation (solar radiation, MJ m−2), mean annual climate moisture index (CMI, cm) and decadal cumulative N deposition (ND, g m−2) preceding the second census as proxies for environmental resource availabilities. The solar radiation and CMI were extracted from the BioSIM software (https://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/projects/133), which generates long-term, scale-free climate data based on geographic coordinates (latitude, longitude, and elevation)68. We used N deposition data at a 0.5° grid from ISIMIP69,70. The CMI was calculated as mean annual precipitation minus potential evapotranspiration71. The decadal mean annual heatwave intensity (HI) preceding the second census and mean soil pH between the two censuses were used as environmental non-resource stress indices. Higher HI values indicate more intense heatwave events in the past ten years, while sites with low soil pH (acidity stress) might reduce plant growth by inhibiting the uptake of essential elements and causing specific-ion toxicities. The HI was defined as a period with 3 consecutive days or longer with daily mean temperatures greater than the 90th percentile of temperature over a 30-year historical baseline period72. The HI, calculated with the ‘heatwaveR’ package, represents an annual cumulative heatwave intensity value, where the intensity is determined by the difference between mean temperatures during each heatwave event and the threshold temperatures72. In addition to decadal cumulative N deposition, we also used the corresponding soil C/N ratios in each plot as an index of soil N condition. These plots were also grouped into two main biomes: temperate forests and boreal forests, following the classification of the World Wildlife Foundation (http://worldwildlife.org)73.

Statistical analyses

The C accumulation in tree biomass, soil organic and mineral horizons, and the N accumulation in soil organic and mineral horizons were considered our response variables and analyzed separately. To explore how the relationships between tree functional diversity and C and N accumulation in trees and soils varied across environmental resource gradients after accounting for the effect of stand age and tree community functional identity, we used the following linear model:

where βi and ɛ are the coefficients to be estimated and the sampling error, respectively. FDis, CWMPC1, and CWMPC2 are functional diversity and CWM of the first and second dimensions of variations in functional traits. The Solar, CMI, and ND are environmental gradient indices for solar energy, water availability, and N availability. The stand age (SA) and forest functional identity (CWMPC1 and CWMPC2) were included as covariates. As an alternative to ND, we also investigated how the relationships between tree functional diversity and C and N accumulation in trees and soils varied across a soil N availability gradient by replacing ND with soil C/N ratios in the organic or mineral horizon.

To explore how the relationships between tree functional diversity and C and N accumulation in trees and soils varied across environmental non-resource stress factors after accounting for the effect of stand age and tree community functional identity, we used the following linear model:

where HI and pH are non-resource stress indices for heatwave and soil acidity. The stand age (SA) and forest functional identity (CWMPC1 and CWMPC2) were included as covariates.

All explanatory variables were centered and scaled (mean = 0, SD = 1) before the analysis to permit the proper comparison of the resulting model coefficients. To prevent overfitting74, we selected the most parsimonious model based on the lowest AIC among all alternatives using the ‘dredge’ function in the muMIn package75 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 1~4). Collinearity among explanatory variables was tested by variance inflation factors (VIFs). We found that all predictors had VIF < 5; hence, there was no multicollinearity in the most parsimonious models76. Thus, we report results for the most parsimonious models in this paper. However, solar radiation is highly geographically intercorrelated with MAT (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2), which is a surrogate for chemical energy and plays a dominant role in controlling ecological systems and processes. We used a stepwise approach to disentangle the impacts of solar radiation from temperature. First, we replaced the term solar radiation with MAT in the initial full models and then included both terms in the initial full models, yet we did not find any significant interactive effects between MAT and FDis on C and N accumulation in trees and soils. Second, we added MAT and its interaction with FDis as a covariate in the most parsimonious model and found that the models with and without MAT and its interaction yielded qualitatively similar estimates and trends (Supplementary Table 8). In the model including both solar radiation and MAT on tree biomass C accumulation, only solar radiation was significant (F = 10.84, df = 1, P = 0.001, Supplementary Table 8). The linear three-dimensional regression model that included both solar radiation and MAT also showed that C accumulation in tree biomass depended not only on MAT, but also on solar radiation (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Finally, given that solar radiation was included in the most parsimonious model for C accumulation in tree biomass, we calculated the residuals of C accumulation in tree biomass with respect to MAT and subsequently modeled these residuals instead of raw data of tree biomass C accumulation as a function of variables in the most parsimonious model to avoid problems stemming from correlations and colinearity between solar radiation and MAT. Even after the MAT effect was removed, the solar radiation effect on tree biomass C accumulation was still significant (F = 6.64, df = 1, P = 0.010, Supplementary Fig. 5b). Even after all plots were grouped into two biomes (temperate and boreal forests) based on the mean annual air temperature, we did not found significant interactions between FDis and biome on C and N accumulation in trees and soils (Supplementary Table 9).

We used partial regressions to graphically illustrate the effects of Solar, CMI, ND, HI, and soil pH on relationships between tree functional diversity and C and N accumulation in trees and soils. We calculated Solar-, CMI-, ND-, HI- and soil pH-dependent functional diversity effects as β0 + β5·FDis + β2·Solar (or CMI, ND, HI, pH) × FDis for the mean, and mean plus and minus one standard deviation of Solar, CMI, ND, HI, and soil pH, respectively. We examined the spatial dependence of model residuals using Moran’s I test implemented in the spdep package in R77, revealing no discernible autocorrelation. Significance was set at α = 0.05 for all analyses unless otherwise stated. We used a one-sided F-test to calculate P values. All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.3.178.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data on tree biomass carbon accumulation, soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation, and local environmental condition generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25037213. The raw tree and soil data are available under restricted access for scientific research-only use, and access can be obtained by application at https://nfi.nfis.org/en/.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available in the Figshare database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25037213.

References

Pan, Y. D. et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333, 988–993 (2011).

Reich, P. B., Grigal, D. F., Aber, J. D. & Gower, S. T. Nitrogen mineralization and productivity in 50 hardwood and conifer stands on diverse soils. Ecology 78, 335–347 (1997).

Drever, C. R. et al. Natural climate solutions for Canada. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6034 (2021).

Mori, A. S. et al. Biodiversity-productivity relationships are key to nature-based climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 543–550 (2021).

Chen, X. L., Chen, H. Y. H., Searle, E. B., Chen, C. & Reich, P. B. Negative to positive shifts in diversity effects on soil nitrogen over time. Nat. Sustain 4, 225–234 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. Impacts of species richness on productivity in a large-scale subtropical forest experiment. Science 362, 80–83 (2018).

Chen, X. L. et al. Tree diversity increases decadal forest soil carbon and nitrogen accrual. Nature 618, 94–101 (2023).

Lange, M. et al. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 6, 6707 (2015).

Mori, A. S. Environmental controls on the causes and functional consequences of tree species diversity. J. Ecol. 106, 113–125 (2018).

Maestre, F. T., Valladares, F. & Reynolds, J. F. Is the change of plant-plant interactions with abiotic stress predictable? A meta-analysis of field results in arid environments. J. Ecol. 93, 748–757 (2005).

Wardle, D. A. & Zackrisson, O. Effects of species and functional group loss on island ecosystem properties. Nature 435, 806–810 (2005).

Barry, K. E. et al. The future of complementarity: disentangling causes from consequences. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 167–180 (2019).

Bertness, M. D. & Callaway, R. Positive interactions in communities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 191–193 (1994).

Mina, M., Huber, M. O., Forrester, D. I., Thürig, E. & Rohner, B. Multiple factors modulate tree growth complementarity in Central European mixed forests. J. Ecol. 106, 1106–1119 (2018).

Maestre, F. T., Callaway, R. M., Valladares, F. & Lortie, C. J. Refining the stress-gradient hypothesis for competition and facilitation in plant communities. J. Ecol. 97, 199–205 (2009).

Michalet, R., Le Bagousse-Pinguet, Y., Maalouf, J. P. & Lortie, C. J. Two alternatives to the stress-gradient hypothesis at the edge of life: the collapse of facilitation and the switch from facilitation to competition. J. Veg. Sci. 25, 609–613 (2014).

Reich, P. B. et al. Plant diversity enhances ecosystem responses to elevated CO2 and nitrogen deposition. Nature 410, 809–810 (2001).

Belluau, M., Vitali, V., Parker, W. C., Paquette, A. & Messier, C. Overyielding in young tree communities does not support the stress-gradient hypothesis and is favoured by functional diversity and higher water availability. J. Ecol. 109, 1790–1803 (2021).

Fridley, J. D. Diversity effects on production in different light and fertility environments: an experiment with communities of annual plants. J. Ecol. 91, 396–406 (2003).

Cowles, J. M., Wragg, P. D., Wright, A. J., Powers, J. S. & Tilman, D. Shifting grassland plant community structure drives positive interactive effects of warming and diversity on aboveground net primary productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 741–749 (2016).

Jucker, T. et al. Climate modulates the effects of tree diversity on forest productivity. J. Ecol. 104, 388–398 (2016).

Ratcliffe, S. et al. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning relations in European forests depend on environmental context. Ecol. Lett. 20, 1414–1426 (2017).

Hisano, M. & Chen, H. Y. H. Spatial variation in climate modifies effects of functional diversity on biomass dynamics in natural forests across Canada. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 682–695 (2020).

Lin, S. X., Fan, C. Y., Zhang, C. Y., Zhao, X. H. & von Gadow, K. Anthropogenic disturbance mediates soil water effect on diversity-productivity relationships in a temperate forest region. Ecol. Manag. 525, 120544 (2022).

van der Voort, T. S. et al. Variability in C-14 contents of soil organic matter at the plot and regional scale across climatic and geologic gradients. Biogeosciences 13, 3427–3439 (2016).

Nemani, R. R. et al. Climate-driven increases in global terrestrial net primary production from 1982 to 1999. Science 300, 1560–1563 (2003).

Reich, P. B. et al. Effects of climate warming on photosynthesis in boreal tree species depend on soil moisture. Nature 562, 263–267 (2018).

Gundale, M. J., Nilsson, M., Bansal, S. & Jäderlund, A. The interactive effects of temperature and light on biological nitrogen fixation in boreal forests. N. Phytol. 194, 453–463 (2012).

De Deyn, G. B., Cornelissen, J. H. & Bardgett, R. D. Plant functional traits and soil carbon sequestration in contrasting biomes. Ecol. Lett. 11, 516–531 (2008).

Sun, Z. et al. Spatial pattern of GPP variations in terrestrial ecosystems and its drivers: Climatic factors, CO2 concentration and land-cover change, 1982–2015. Ecol. Inform. 46, 156–165 (2018).

Churkina, G. & Running, S. W. Contrasting climatic controls on the estimated productivity of global terrestrial biomes. Ecosystems 1, 206–215 (1998).

Teskey, R. et al. Responses of tree species to heat waves and extreme heat events. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 1699–1712 (2015).

Luo, S. et al. Higher productivity in forests with mixed mycorrhizal strategies. Nat. Commun. 14, 1377 (2023).

Shortle, W. C. & Smith, K. T. Aluminum-induced calcium deficiency syndrome in declining red spruce. Science 240, 1017–1018 (1988).

Woolery, M. E., Olson, K. R., Dawson, J. O. & Bollero, G. Using soil properties to predict forest productivity in southern Illinois. J. Soil Water Conserv 57, 37–45 (2002).

Williams, L. J. et al. Enhanced light interception and light use efficiency explain overyielding in young tree communities. Ecol. Lett. 24, 996–1006 (2021).

Chen, X. L. & Chen, H. Y. H. Plant diversity loss reduces soil respiration across terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1482–1492 (2019).

Preston, C. M., Bhatti, J. S., Flanagan, L. B. & Norris, C. Stocks, chemistry, and sensitivity to climate change of dead organic matter along the Canadian Boreal forest transect case study. Clim. Change 74, 223–251 (2006).

Pastore, M. A., Hobbie, S. E. & Reich, P. B. Sensitivity of grassland carbon pools to plant diversity, elevated CO2, and soil nitrogen addition over 19 years. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 118, e2016965118 (2021).

Reich, P. B. et al. Species and functional group diversity independently influence biomass accumulation and its response to CO2 and N. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 101, 10101–10106 (2004).

Ma, Z. L. & Chen, H. Y. H. Effects of species diversity on fine root productivity increase with stand development and associated mechanisms in a boreal forest. J. Ecol. 105, 237–245 (2017).

Spohn, M. et al. The positive effect of plant diversity on soil carbon depends on climate. Nat. Commun. 14, 6624 (2023).

Anjileli, H. et al. Extreme heat events heighten soil respiration. Sci. Rep.-Uk 11, 6632 (2021).

Aguirre-Gutiérrez, J. et al. Functional susceptibility of tropical forests to climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 878–889 (2022).

Staples, T. L., Dwyer, J. M., England, J. R. & Mayfield, M. M. Productivity does not correlate with species and functional diversity in Australian reforestation plantings across a wide climate gradient. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 28, 1417–1429 (2019).

Button, K. S. et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 365–376 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Significant soil acidification across northern China’s grasslands during 1980s–2000s. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2292–2300 (2012).

National Forest Inventory. Canada’s National Forest Inventory –ground-plot data, version 2.0. (2021).

National Forest Inventory. Canada’s National Forest Inventory – ground-sampling guidelines, version 5.0. Available from http://nfi.nfis.org. (2008).

Lambert, M. C., Ung, C. H. & Raulier, F. Canadian national tree aboveground biomass equations. Can. J. For. Res 35, 1996–2018 (2005).

Martin, A. R., Doraisami, M. & Thomas, S. C. Global patterns in wood carbon concentration across the world’s trees and forests. Nat. Geosci. 11, 915–920 (2018).

Chen, H. Y. H. & Klinka, K. Aboveground productivity of western hemlock and western redcedar mixed-species stands in southern coastal British Columbia. Ecol. Manag. 184, 55–64 (2003).

British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Range and British Columbia Ministry of Environment Field manual for describing terrestrial ecosystems. 2nd ed. (Land Management Handbook No. 25, Forest Science Program, Victoria, B.C.; 2010).

Pearson, T. R. Measurement guidelines for the sequestration of forest carbon. (United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Nortjern Research Station, USA, 2007).

Reich, P. B. The world-wide ‘fast-slow’ plant economics spectrum: a traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 102, 275–301 (2014).

Carol Adair, E., Hooper, D. U., Paquette, A. & Hungate, B. A. Ecosystem context illuminates conflicting roles of plant diversity in carbon storage. Ecol. Lett. 21, 1604–1619 (2018).

Kunstler, G. et al. Plant functional traits have globally consistent effects on competition. Nature 529, 204–207 (2016).

Kattge, J. et al. TRY - a global database of plant traits. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2905–2935 (2011).

Laliberte, E. & Legendre, P. A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 91, 299–305 (2010).

Ruiz-Benito, P. et al. Climate- and successional-related changes in functional composition of European forests are strongly driven by tree mortality. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4162–4176 (2017).

Hisano, M., Ryo, M., Chen, X. & Chen, H. Y. H. Rapid functional shifts across high latitude forests over the last 65 years. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 3846–3858 (2021).

Chen, X., Hisano, M., Taylor, A. R. & Chen, H. Y. H. The effects of functional diversity and identity (acquisitive versus conservative strategies) on soil carbon stocks are dependent on environmental contexts. Ecol. Manag. 503, 119820 (2022).

Diaz, S. et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 529, 167–173 (2016).

Wright, I. J. et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428, 821–827 (2004).

Conti, G. & Diaz, S. Plant functional diversity and carbon storage - an empirical test in semi-arid forest ecosystems. J. Ecol. 101, 18–28 (2013).

Zeugin, F., Potvin, C., Jansa, J. & Scherer-Lorenzen, M. Is tree diversity an important driver for phosphorus and nitrogen acquisition of a young tropical plantation? Ecol. Manag. 260, 1424–1433 (2010).

Pietsch, K. A. et al. Global relationship of wood and leaf litter decomposability: the role of functional traits within and across plant organs. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 1046–1057 (2014).

Régnière, J. & Saint-Amant, R. Natural Resources Canada. (Laurentian Forestry Centre, Quebec City, Canada, 2008).

Tian, H. Q. et al. The global N2O model intercomparison project. B Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 1231–1252 (2018).

Lamarque, J. F. et al. Multi-model mean nitrogen and sulfur deposition from the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP): evaluation of historical and projected future changes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 7997–8018 (2013).

Hogg, E. H. Temporal scaling of moisture and the forest-grassland boundary in western Canada. Agr. Meteorol. 84, 115–122 (1997).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on earth: A new global map of terrestrial ecoregions provides an innovative tool for conserving biodiversity. BioScience 51, 933–938 (2001).

Johnson, J. B. & Omland, K. S. Model selection in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 101–108 (2004).

Barton, K. MuMIn: multi-model inference, R package version. (2009).

González-Suárez, M. & Revilla, E. Variability in life-history and ecological traits is a buffer against extinction in mammals. Ecol. Lett. 16, 242–251 (2013).

Bivand, R. et al. Package ‘spdep’. 0.7-7 (2018).

R Core Team (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to E. B. Searle for his editorial comments during the revision. Canadian Forest Service of the Natural Resources Canada shared the data from the National Forest Inventory database. X.C. acknowledges the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 32401546), NSFC Excellent Young Scientists Fund (overseas), the Scientific Research Startup Fund Project of Zhejiang A&F University (2024LFR019), NSERC in the form of a and a MITACS internship. S.X.C. acknowledges the support from a Discovery grant (RGPIN-2018-05700) of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). PBR was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation ASCEND Biology Integration Institute (NSF-DBI-2021898).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C., P.B.R., and S.X.C. were responsible for the conception and design of the project. X.C. and A.R.T. compiled data. X.C. analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. X.C., P.B.R., A.R.T., Z.A., and S.X.C. contributed to reviewing and editing. S.X.C. supervised the work and acquired funding. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion & ethics

For this research, local researchers were included throughout the research process including study design, study implementation, data ownership, and authorship. Contributors who do not meet all criteria for authorship have been listed in the Acknowledgements section. All roles and responsibilities were agreed amongst collaborators ahead of the research. We have considered local and regional research relevant to our study in the citations. This study does not involve human research participants or animals and does not require approval by a local ethics review committee.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Reich, P.B., Taylor, A.R. et al. Resource availability enhances positive tree functional diversity effects on carbon and nitrogen accrual in natural forests. Nat Commun 15, 8615 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53004-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53004-y

This article is cited by

-

Large slow-growing hydrophytes increase wetland carbon storage

Nature Plants (2026)

-

Leaf and seed traits reflect resource strategies in Corema album populations

Plant Ecology (2026)

-

Wetland productivity and stability increase more with average plant size than with plant functional diversity

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Environmental change shapes understory plant diversity and dominance in boreal forests

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Arbor‒shrub mixed vegetation restoration strategies enhanced soil organic carbon storage and stability via fine root and fungal characteristics in limestone hills

Plant and Soil (2025)