Abstract

Aromatic belts, ultrashort carbon nanotubes, and related structures, are emerging molecular entities in the fields of organic electronics and supramolecular chemistry owing to their structural rigidity, fully fused π-conjugation, and well-defined cavity. Synthesis of aromatic belts with embedded thiophene structures, which manifest significant optoelectronic and conductive properties, has not yet been achieved. Herein, we report the synthesis of thiophene-fused aromatic belts (thiophene belts) via one-step sulfur cross-linking reaction of partially fluorinated cycloparaphenylenes. Their structural features, including unidirectional columnar stacking with high dipole moment in crystals, two-dimensional layer assembly on metal surfaces, and photophysical properties, such as long-lifetime phosphorescence, are uncovered. These distinctive features of the thiophene belts should inspire a range of applications such as optoelectronic devices and polar materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

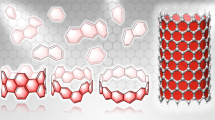

Aromatic belts, ultrashort carbon nanotubes, and related structures have been of interest to theoretical chemists as well as synthetic and physical chemists for over 70 years1,2,3,4,5. Stimulated by our first synthesis of a (6,6)carbon nanobelt in 20176, many research groups have successfully synthesized a range of carbon nanobelts and related aromatic belts3,7,8,9,10,11,12, which are emerging molecular entities in the fields of organic electronics and supramolecular chemistry owing to their structural rigidity, fully fused π-conjugation, and well-defined cavity. Their rigid and hollow structures, which can be regarded as ultrashort carbon nanotubes, are expected to have a variety of applications, such as host–guest chemistry and optoelectronic materials2,3,13,14. Importantly, Zang et al. demonstrated that nanobelts have high conductance in single-molecule devices, highlighting the importance of radial π-conjugation for high conductivity14. When considering applications in the field of organic electronics, there are many reasons for investigating and incorporating fused thiophenes, which are known to be multifunctional and monopolistic core structures. As representatives of electron-donating π-electron systems, fused thiophenes are widely used as the basic backbone of p-type organic semiconductors, molecular conductors, and light-emitting materials15,16,17,18. Therefore, the synthesis of aromatic belts that incorporate fused thiophenes should lead to the provision of nanobelts with new functions. Herein, we report the synthesis of thiophene-fused aromatic belts (thiophene belts) via one-step sulfur cross-linking of partially fluorinated cycloparaphenylenes (CPPs) (Fig. 1a). Their structural features, including unidirectional columnar stacking with high dipole moment in crystals, two-dimensional layer assembly on metal surfaces, and photophysical properties, such as long-lifetime phosphorescence, were uncovered. These distinctive features of the thiophene belts should inspire a range of applications such as optoelectronic devices and polar materials.

a Fusion of nanobelt chemistry and thiophene chemistry. b Plotting strain energies versus n (number of benzene rings) and cone-shaped (n = 6–18), flat-shaped (n = 18–26), and saddle-shaped structures (n = 28–36) of thiophene belts. c Scheme for the syntheses of thiophene belts 1 and 2. Na2S, sodium sulfide; NBu4Br, tetrabutylammonium bromide; HMPA, hexamethylphosphoric triamide.

Results and discussion

Structure prediction and synthesis of thiophene belts

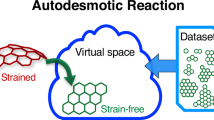

Before investigating the synthesis of thiophene belts, strain energy calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31 G(d) level of theory to understand their structural properties. The strain energy was calculated using a hypothetical homodesmotic reaction (Fig. 1b)19. When the diameter is small (n = 6–18; n indicates the number of thiophene units), the thiophene belts adopt cone-shaped structures with a strain energy behavior similar to that of previously reported nanobelts. Thiophene belts are most stable in flattened structures when their diameter exceeds a certain threshold (n = 18–26). In the larger thiophene belts (n = 28–36), the shapes are the same as those of the saddle-shaped surfaces. The change in shape with an increasing number of repeating units is similar to that of sulflowers20 or cyclothiophenes21,22,23.

In this study, cone-shaped thiophene belts were synthesized (Fig. 1c). Among various theoretical approaches, we envisioned a ring-to-belt synthesis through the late-stage sulfur-embedding reaction of a CPP core24,25,26. Thus, significant strain energy gain is not required during the difficult belt-forming events5. For the C–S bond formation, we chose nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) reactions at the C–F bonds because of their reliability and simplicity27. Thus, [8]thiophene belt (1) and [9]thiophene belt (2) were synthesized from the corresponding half-fluorinated CPPs, F16[8]CPP and F18[9]CPP. Following extensive investigations, we found that the starting materials (F16[8]CPP and F18[9]CPP) can be synthesized via our nickel-based method28,29 and Tsuchido’s gold-based method30,31 from readily available 2,2’,3,3’-tetrafluorobiphenyl. Details of the synthesis are provided in Supplementary Information (page S6–S11). For key sulfur-embedding SNAr reactions, the conditions reported by Amsharov are particularly effective32. Thus, a mixture of F16[8]CPP (1.0 equiv), sodium sulfide (80 equiv.), and tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB: 16 equiv.) in hexamethylphosphoric triamide (HMPA) was heated at 180 °C for 3 h under microwave irradiation. Following purification by precipitation, washing, and silica gel chromatography, the [8]thiophene belt (1) was successfully isolated in 20% yield as a stable yellow solid (Fig. 1c). Under similar SNAr reaction conditions, F18[9]CPP was converted to [9]thiophene belt (2) in 16% isolated yield (Fig. 1c). Despite the large number of reaction points (16 C–F bonds for 1, 18 C–F bonds for 2), both reactions proceeded with approximately 90% efficiency per C–F bond. However, because F12[6]CPP29 did not tolerate the reaction conditions, [6]thiophene belt was not obtained.

In the 1H NMR spectra of 1 and 2, only singlet signals were observed in both cases (Fig. S39 and S40). Structural optimization by density functional theory (DFT) calculations resulted in structures with high symmetry of C8v for 1 and C9v for 2. The results of NMR analysis and calculations suggest that the thiophene belts have high symmetry, even in solution. The NMR signals of hydrogen atoms in the thiophene belts were found to be of a lower magnetic field shifted than that of CPP (1: 7.72 ppm, [8]CPP: 7.48 ppm, 2: 7.85 ppm, [9]CPP: 7.52 ppm, see Fig. S38)26,33. This can be interpreted as a result of the stronger anti-shielding effect of hydrogen atoms owing to the belt-like structural constraint of the CPP backbone by sulfur cross-linking.

Crystal structures and packing of thiophene belts

Suitable single crystals of 1 and 2 were obtained from solutions of dichloromethane for 1 and chlorobenzene for 2, respectively. Their structures were successfully determined using X-ray crystallography. As shown in Figs. 2a, 1 and 2 adopt belt-shaped and truncated conical structures (C8v and C9v symmetries, respectively). These unique shapes result from a structure in which only one side of the CPP backbone is cross-linked with sulfur atoms. The taper angles of the conical structures in each thiophene belt are 50° for 1 and 58° for 2, respectively. Consistent with the DFT calculation results, the angle increases with increasing belt size. The measured diameters of the inscribed and circumscribed circles in the observed structures of thiophene belts are 8.67 Å and 12.9 Å for 1, 9.75 Å and 14.2 Å for 2, respectively (Fig. 2a and b, center and right). Another interesting feature of thiophene belts is that they are neutral, yet significantly polar molecules because the sulfur atoms are clustered on one side of the belts. According to DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31 G(d) level of theory with dispersion correction of Grimme’s D3, the electrostatic potential map shows that the negative potential density is concentrated on the sulfur side. In addition, 1 is estimated to have a dipole moment of 8.21 Debye and 2 has that of 8.92 Debye. The results show that polarity increases with the increasing number of sulfur atoms with the cone-shaped nanobelt structures (Fig. 2e, also see Fig. S20 and S21).

The Oak Ridge thermal-ellipsoid plot (ORTEP) drawings of 1 and 2 with thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability (a for 1, b for 2, center: side views and taper angles, right: top views, diameters of inscribed circle and circumscribed circle). Solvent molecules are omitted for clarity. c Packing structures of 1 and 2. Solvent molecules (dichloromethane for the left, and chlorobenzene for the right) are omitted for clarity. d Non-covalent interaction (NCI) plot of 2 visualizing intramolecular interactions using X-ray structure. An isosurface value of 0.30 a.u. is applied to the structure. e Electrostatic surface potential maps calculated for 2 with isovalues plotted at 0.001 and the value of dipole moment for 2. f Unit cell structure for 2 and the value of dipole moment per unit cell.

Despite the use of thiophene belts of various sizes and different solvents to prepare the crystals, all packing structures for 1 and 2 were stacked in a columnar manner (Fig. 2c, left: dichloromethane for 1, and right: chlorobenzene for 2, benzene/pentane and chloroform/pentane for 1: see Fig. S4). Since certain bowl-shaped molecules are known to form columnar stacks34,35,36,37,38, the conical structures of the thiophene belts may stabilize columnar packing, as visualized by the non-covalent interaction (NCI) plot (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, because each column is oriented in the same direction, the crystals of the thiophene belts provide space with broken spatial symmetry (Fig. 2c). In the case of thiophene belts, all adjacent columns in the crystals of 1 and 2 are not perfectly parallel but are aligned with a half-molecular translation of the thiophene belt. Non-polar assemblies are often advantageous because the antiparallel orientation of the dipoles in each column is more electrostatically favorable than the parallel orientation34. The intermolecular distance between columns is 2.73 Å for 2, which corresponds to the CH–π interaction (Fig. 2d). The packing of thiophene belts can efficiently generate CH–π interactions like herringbone due to the inclination of the conical structures. The calculations also show that the crystals, including the solvent in 2, are polar crystals (36.6 Debye per unit cell, Fig. 2f). Polar materials and single crystals are of significant interest owing to their unique properties such as ferroelectricity and the bulk photovoltaic effect34,35,39,40,41,42,43. Moreover, this remarkable column-forming tendency of the thiophene belts was observed in the just-evaporated sample of 2 supported by the powder X-ray diffraction pattern (Fig. S5). The tubular space surrounded by sulfur atoms, given by the characteristic structure of the belt, has no similar examples. These features, coupled with manifesting one-dimensional and parallel-orienting polar assemblies, stimulate the use of thiophene belts for various optoelectronic applications.

Photophysical and electrochemical properties of thiophene belts

Optical and electrochemical measurements as well as DFT calculations were performed to investigate the optoelectronic properties of thiophene belts. The ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) absorption of dichloromethane solutions of 1 and 2 exhibit absorption peaks at 345 nm and 351 nm, respectively (Fig. 3a, solid green and blue lines, respectively). In the case of 1, the peak top is red-shifted compared to that of pristine [8]CPP ([8]CPP: 339 nm) and blue-shifted compared to that of methylene-bridged [8]cycloparaphenylene ([8]MCPP: 388 nm)44, which has a rigid CPP moiety similar to 1. In the case of 2, the top of the peak is slightly red-shifted from that of pristine [9]CPP (340 nm), as in the case of 1. The absorption edges of 1 and 2 are observed at approximately 470 and 450 nm, respectively. Time-dependent (TD)-DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31 G(d) level with dispersion correction of Grimme’s D3 revealed the transitions attributable to each peak (Fig. S14 and S15, Table S5). Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements determined that compound 1 has two oxidation potentials, with E1 = 0.72 V and E2 = 0.86 V vs ferrocene(II)/ferrocenium(III) (Fig. S13). Since [8]CPP has an oxidation potential of E = 0.59 V45, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) level of 1 is elevated due to the electron-donating effect of the sulfur atoms. Considering that [8]CPP has a two-electron oxidation process in a single step, the two-step oxidation steps of 1 are presumed to be one-electron processes. This suggests that the radical cation of 1 might be stabilized by the sulfur atoms. The HOMO and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of 1 reflect the fused structure of cyclothiophenes21,22,23 and CPPs46 whereas HOMO and HOMO–1 reflect the isoelectronic structure17 of cyclophenacene, which is an unsynthesized aromatic belt (Fig. 3b, also see Fig. S17 and S18)2,3.

a Ultraviolet–visible absorption and fluorescence spectra of the diluted dichloromethane solution of thiophene belts at room temperature (abs: solid lines, flu: dashed lines, green for 1 and blue for 2). The fluorescence quantum yield and lifetime are shown in the upper right corner. Phosphorescence spectra of thiophene belts in 2-methyltetrahydrofuran at 77 K upon excitation at 350 nm (long dashed lines, pink for 1 and orange for 2). The phosphorescence quantum yield and lifetime for 2 are shown in the upper right corner. b Structures and frontier molecular orbitals calculated at the B3LYP/6-31 G(d) level of theory with dispersion correction of Grimme’s D3 (isovalue: 0.02) of 1 (yellow square), cyclothiophene (left gray square), and cycloparaphenylene (right gray square) of the same ring-size as 1. Blue and red indicate negative and positive wave functions, respectively; HOMO, highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital. HOMO and LUMO of 1 reflect the fused structure of cyclothiophene and cycloparaphenylene.

In the fluorescence measurements, dichloromethane solutions of 1 and 2 exhibit fluorescence with peaks at 521 nm for 1 and 496 nm for 2 (Fig. 3a, dashed green and blue lines). The maximum fluorescence wavelength of 1 is blue-shifted compared to those of [8]CPP and [8]MCPP ([8]CPP: 541 nm, [8]MCPP: 592 nm)44. While no vibrational structures were observed in the fluorescence of the pristine CPPs, vibrational structures were observed in the thiophene belts, most likely because of their rigid structures. Nanobelts 1 and 2 exhibit fluorescence quantum yield (ΦF) of 0.03 and 0.27, respectively, the latter being smaller than that observed for [9]CPP (ΦF = 0.73, Fig. S8). The observed lower ΦF for 2, despite the more rigid structure, can be attributed to the strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC) exhibited by the sulfur atoms47. The fluorescence lifetimes of the thiophene belts were estimated to be 2.64 ns for 1 and 4.74 ns for 2, respectively. According to the equations ΦF = kr × τ and kr + knr = τ−1, the radiative (kr) and nonradiative (knr) decay rate constants from the singlet excited state are determined as kr = 1.1 × 107 s−1; knr = 3.7 × 108 s−1 for 1, kr = 5.7 × 107 s−1; knr = 1.5 × 108 s−1 for 2.

Importantly, phosphorescence was observed at low temperature (77 K). The phosphorescence spectra of 2-methyltetrahydrofuran solutions of 1 and 2 exhibit peaks at 592 and 565 nm, respectively, corresponding to vibrational structures (Fig. 3a, dashed orange and pink lines). The phosphorescence of 1 could not exclude the minor peak on the short-wavelength side of the major peak, owing to unremovable trace amounts of impurities. The phosphorescence spectra of thiophene belts are considerably blue-shifted compared to those of CPPs, and the size dependency is consistent with the behavior of the phosphorescence spectra of CPPs ([8]CPP: 671 nm, [9]CPP: 633 nm)48. The phosphorescence quantum yield (Φphos) for 2 is 0.096. The phosphorescence lifetimes of the thiophene belts were also measured (Fig. 3a, also see Fig. S12). Long-lifetime phosphorescence was observed in one component for 2 (τphos = 130 ms). The phosphorescence lifetimes of the thiophene belts are more than 1000 times longer than those of CPPs ([8]CPP: 0.060 ms, [9]CPP: 0.063 ms)48. Usually, in π-conjugated molecules, high-frequency vibrational modes inevitably accelerate nonradiative deactivation49. The long phosphorescence lifetime observed in 2 compared to that of [9]CPP may be due to the rigid sulfur-bridged belt structure, which reduces the number of C–H bonds and their stretch modes, suppressing vibrational deactivation. Nevertheless, the observed long-lived excited triplet states are of interest as this feature is essential in the emerging fields of triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion50 and photo-induced dynamic nuclear polarization51.

Assembly of thiophene belts on metal surfaces

The synthesized thiophene belts are defined by all sulfur atoms pointing in the same direction, resulting in a high dipole moment. To investigate how this dipole and the metal-sulfur interactions influence the nucleation of these molecular tubes on metal surfaces, scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) in conjunction with DFT simulations was performed. Therefore, belt 1 was deposited on the Au(111) and Cu(111) surfaces by sublimation at a deposition temperature of 350 °C. Adsorbed single molecules can be identified straightforwardly by their distinct circular contrast in constant current STM, which further proves a successful synthesis and deposition of the thiophene belts. Imaging at a bias voltage of 2 V, the diameter of the ring can be estimated to be 8.3 Å, which matches the calculated size of 1 (Fig. S28). On the Au(111) surface, 1 is predominantly nucleated at the step edges at low coverages (Fig. 4a). In contrast, on the Cu(111) surface, islands of self-assembled thiophene belts were observed in a two-dimensional densely ordered packing (Fig. 4d). The measurements suggest that the observed assemblies are of single-molecular height on both the Au and Cu surfaces and that there is no stacking at these coverages (Fig. S26 and S27). Generally, pristine CPPs decompose at high temperatures owing to their high strain energies. Therefore, previously reported STM images of the CPP derivatives were prepared using the drop-cast method52. As shown by the present measurements, 1 withstood sublimation temperatures as high as 350 °C, which suggests that the linking of the CPP scaffold with sulfur atoms significantly increases the stability of 1.

a STM image of 1 on the Au(111) surface (Bias voltage 2 V, Setpoint current 10 pA). Image in the range of 100 nm, 24 nm, and 12 nm, respectively. Schematic of 1 with sulfur atoms facing up for b, and sulfur atoms facing down for c. Top view of geometry-optimized facing up or down (center of b and c, respectively) 1 as self-assembly on Au surface. Simulated STM image and binding energy with sulfur atoms facing up and down (right of b and c, respectively). d STM image of 1 on the Cu(111) surface (Bias voltage 2 V, Setpoint current 10 pA). Image in the range of 50 nm, 10 nm, and 4 nm, respectively. Schematic of 1 with sulfur atoms facing up for e and sulfur atoms facing down for f. Geometry-optimized top view of facing up or down (center of e and f, respectively) 1 as self-assembly on Cu surface. Simulated STM image and binding energy with sulfur atoms facing up and down (right of e and f, respectively).

To clarify whether the sulfur atoms of 1 face up or down on the metal surfaces, DFT calculations and STM simulations were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)53,54 (Fig. 4b, c, e, and f). On the Au(111) surface, the structure with sulfur atoms facing down toward the Au step edges is in better agreement with the measured data of the STM images, whereas on the Cu(111) surface, the structure with sulfur atoms facing up toward the Cu surface shows better agreement. Furthermore, the binding energies of 1 under upward- and downward-facing sulfur atoms on both Au and Cu surfaces were calculated. On the Au(111) surface, the calculations emphasize that conformations with sulfur contacts pointing toward the metal step edges are preferred (ΔEbind,S-up = 2.16 eV and ΔEbind,S-down = 2.42 eV; Fig. 4b and c). Remarkably, the experiments on Au(111) further show that the thiophene belts exclusively show a stable binding conformation at the step edges, while on flat terraces they are more mobile and agglomerate in small islands in a disordered manner (Fig. S26). In contrast, on the Cu(111) surface, the calculations show that the thiophene belt 1 is preferentially aligned with sulfur atoms facing up (ΔEbind,S-up = 2.14 eV and ΔEbind,S-down = 1.97 eV; Fig. 4, e and f), favoring a conformation that enables multiple points of contact (16 C–H bonds) with the metal surface. Therefore, the molecules are more stable on the Cu(111) surface and arranged in ordered islands. In conclusion, the preferred orientation of the thiophene belt may depend on the interaction format of each type of metal.

Focusing on the on-surface dynamics, we hypothesize that the different adsorption modes of the thiophene belt on Au (at the step edge) and Cu (on the flat surface) are due to distinct molecule-substrate interactions. On the Au surface, specific interactions between sulfur atoms and undercoordinated Au atoms at step edges lead to stronger adsorption and stabilization. In contrast, on the Cu surface, probably non-specific dispersion interactions dominate, which depend on the number of interaction sites between the molecule and the surface. The tilting of the molecule at step edges would, in this case, decrease interaction. Therefore, adsorption on the flat Cu surface is presumably preferred.

Thiophene belts with a merged structure of recently emerging aromatic belts and function-rich fused thiophenes have been successfully synthesized via sulfur-embedding ring-to-belt transformations. The established synthetic routes to thiophene belts (1 and 2) are reasonably short-step from readily available 2,2’,3,3’-tetrafluorobiphenyl (two steps for 1 and five steps for 2). Their structural features, such as unidirectional columnar stacking with high dipole moment in crystals as well as in a just-evaporated sample, and metal-dependent assembly on Au(111) and Cu(111) surfaces, as well as photophysical properties, such as long-lifetime phosphorescence, were uncovered. In the context of rather independent yet very exciting developments of aromatic belts and fused thiophenes in the fields of structural organic chemistry and organic electronics, the “merged” molecules (thiophene belts) with significant properties discovered in this study have the potential to stimulate a range of applications in various fields, such as single-molecule electronics, supramolecular materials, photovoltaics, and triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion. While we demonstrated the synthesis of cone-shaped thiophene belts in this study, we believe that the present ring-to-belt transformation strategy would enable access to other thiophene belts with different topologies as well as other heteroatom-embedded aromatic belts. These synthetic and application-oriented campaigns will lead to significant breakthroughs in the science and technology of aromatic belts.

Methods

Synthesis of 1

To a 0.5–2.0 mL microwave vials containing a magnetic stirring bar were added F16[8]CPP (18.0 mg, 20.1 µmol), sodium sulfide (Na2S, 127 mg, 1.63 mmol), tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB, 109 mg, 0.338 mmol), and hexamethylphosphoric triamide (HMPA, 1.6 mL) in air. The reaction mixture was stirred at 180 °C for 3 h with microwave irradiation. After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the reaction mixture was roughly purified by short silica gel column chromatography (eluent: chloroform 200 mL and methanol ca. 10 mL), and then evaporated in vacuo. The roughly purified material was purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography two times (eluent: hexane/dichloromethane/methanol = 80:20:1 and then dichloromethane only). After evaporation of the extracted material from silica gel on preparative thin-layer chromatography, it was washed three times with 2 mL of hexane to afford [8]thiophene belt 1 (3.4 mg, 20%) as a yellow solid.

Synthesis of 2

To a 0.5–2.0 mL microwave vials containing a magnetic stirring bar were added F18[9]CPP (8.60 mg, 8.53 µmol), sodium sulfide (Na2S, 63.5 mg, 0.813 mmol), tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB, 49.5 mg, 0.153 mmol), and hexamethylphosphoric triamide (HMPA, 1.5 mL) in air. The reaction mixture was stirred at 180 °C for 3 h with microwave irradiation. After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the organic layer was extracted with dichloromethane, and then evaporated in vacuo. Hexane (ca. 20 mL) was added to the crude mixture and centrifuged. The resulting precipitate was dispersed in dichloromethane and evaporated. The resulting precipitate was washed three times with 2 mL of hexane, then once with 3 mL of dichloromethane, and finally three times with 2 mL of hexane to afford [9]thiophene belt 2 (1.3 mg, 16%) as a yellow solid.

Data availability

Materials and methods, experimental procedures, photophysical studies, NMR spectra, and computational details are available in the Supplementary Information or from the corresponding authors upon request. The crystallographic data for compounds 1 and 2 are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under CCDC identifiers 2373105–2373107 (www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/). The optimized cartesian coordinates for each basis function are listed in the excel files as source data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Heilbronner, E. Molecular Orbitals in homologen Reihen mehrkerniger aromatischer Kohlenwasserstoffe: I. Die Eigenwerte yon LCAO-MO’s in homologen Reihen. Helv. Chim. Acta 37, 921–935 (1954).

Guo, Q. H., Qiu, Y., Wang, M. X. & Stoddart, J. F. Aromatic hydrocarbon belts. Nat. Chem. 13, 402–419 (2021).

Imoto, D., Yagi, A. & Itami, K. Carbon nanobelts: brief history and perspective. Precis. Chem. 1, 516–523 (2023).

Schaller, G. R. & Herges, R. Aromatic belts as sections of nanotubes in Fragments of Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes: Designed Synthesis, Unusual Reactions, and Coordination Chemistry, M. A. Petrukhina, L. T. Scott Eds. pp. 259–258 (Wiley, 2011).

Cheung, K. Y., Segawa, Y. & Itami, K. Synthetic strategies of carbon nanobelts and related belt-shaped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem. Eur. J. 65, 14791–14801 (2020).

Povie, G., Segawa, Y., Nishihara, T., Miyauchi, Y. & Itami, K. Synthesis of a carbon nanobelt. Science 356, 172–175 (2017).

Cheung, K. Y. et al. Synthesis of armchair and chiral carbon nanobelts. Chem 5, 838–847 (2019).

Cheung, K. Y., Watanabe, K., Segawa, Y. & Itami, K. Synthesis of a zigzag carbon nanobelt. Nat. Chem. 13, 255–259 (2021).

Han, Y., Dong, S., Shao, J., Fan, W. & Chi, C. Synthesis of a sidewall fragment of a (12,0) carbon nanotube. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2658–2662 (2021).

Xia, Z., Pun, S. H., Chen, H. & Miao, Q. Synthesis of zigzag carbon nanobelts through Scholl reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10311–10318 (2021).

Segawa, Y. et al. Synthesis of a Möbius carbon nanobelt. Nat. Synth. 1, 535–541 (2022).

Fan, W. et al. Synthesis and chiral resolution of a triply twisted Möbius carbon nanobelt. Nat. Synth. 2, 880–887 (2023).

Yamashina, M. et al. An antiaromatic-walled nanospace. Nature 574, 511–515 (2019).

Lin, J. et al. Highly efficient charge transport across carbon nanobelts. Sci. Adv. 8, eade4692 (2022).

Perepichka, I. F. & Perepichka, D. F. Eds., Handbook of Thiophene-Based Materials: Applications in Organic Electronics and Photonics (Wiley, 2009).

Mishra, A., Ma, C. Q. & Bäuerle, P. Functional oigothiophenes: molecular design for multidimensional nanoarchitectures and their applications. Chem. Rev. 109, 1141–1276 (2009).

Takimiya, K., Shinamura, S., Osaka, I. & Miyazaki, E. Thienoacene-based organic semiconductors. Adv. Mater. 38, 4347–4370 (2011).

Larik, F. A. et al. Thiophene-based molecular and polymeric semiconductors for organic field effect transistors and organic thin film transistors. J. Mater. Sci.:Mater. Electron. 29, 17975–18010 (2018).

Segawa, Y., Omachi, H. & Itami, K. Theoretical studies on the structures and strain energies of cycloparaphenylenes. Org. Lett. 12, 2262–2265 (2010).

Chernichenko, K. Y., Sumerin, V. V., Shpanchenko, R. V., Balenkova, E. S. & Nenajdenko, V. G. Sulflower”: a new form of carbon sulfide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 7367–7370 (2006).

Krömer, J. et al. Synthesis of the first fully α-conjugated macrocyclic oligothiophenes: cyclo[n]thiophenes with tunable cavities in the nanometer regime. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 3481–3486 (2000).

Zhang, F., Götz, G., Winkler, H. D. F., Schalley, C. A. & Bäuerle, P. Giant cyclo[n]thiophenes with extended π conjugation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 6632–6635 (2009).

Zade, S. S. & Bendikov, M. Cyclic oligothiophenes: novel organic materials and models for polythiophene. A theoretical study. J. Org. Chem. 71, 2972–2981 (2006).

Jasti, R., Bhattacharjee, J., Neaton, J. B. & Bertozzi, C. R. Synthesis, characterization, and theory of [9]-, [12]-, and [18]cycloparaphenylene: carbon nanohoop structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 52, 17646–17647 (2008).

Takaba, H., Omachi, H., Yamamoto, Y., Bouffard, J. & Itami, K. Selective synthesis of [12]cycloparaphenylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 6112–6116 (2009).

Yamago, S., Watanabe, Y. & Iwamoto, T. Synthesis of [8]cycloparaphenylene from a square-shaped tetranuclear platinum complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 757–759 (2010).

Kamin, A. A. et al. Synthesis and metalation of polycatechol nanohoops derived from fluorocycloparaphenylenes. Chem. Sci. 14, 9724–9732 (2023).

Shudo, H. et al. Perfluorocycloparaphenylenes. Nat. Commun. 13, 3713 (2022).

Shudo, H., Kuwayama, M., Segawa, Y., Yagi, A. & Itami, K. Half-substituted fluorocycloparaphenylenes with high symmetry: synthesis, properties and derivatization to densely substituted carbon nanorings. Chem. Commun. 59, 13494–13497 (2023).

Tsuchido, Y., Abe, R., Ide, T. & Osakada, K. A Macrocyclic gold(I)–biphenylene complex: triangular molecular structure with twisted Au2(diphosphine) corners and reductive elimination of [6]cycloparaphenylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22928–22932 (2020).

Yoshigoe, Y. et al. Dynamic Au–C σ-bonds leading to an efficient synthesis of [n]cycloparaphenylenes (n = 9–15) by self-assembly. JACS Au 2, 1857–1868 (2022).

Feofanov, M., Akhmetov, V., Takayama, R. & Amsharov, K. Y. Facile synthesis of thienoacenes via transition-metal-free ladderization. J. Org. Chem. 86, 14759–14766 (2021).

Segawa, Y., Šenel, P., Matsuura, S., Omachi, H. & Itami, K. [9]Cycloparaphenylene: nickel-mediated synthesis and crystal structure. Chem. Lett. 40, 423–425 (2011).

Zhang, C. et al. A design principle for polar assemblies with C3-Sym bowl-shaped π-conjugated molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3261–3267 (2021).

Furukawa, S. et al. Ferroelectric columnar assemblies from the bowl-to-bowl inversion of aromatic cores. Nat. Commun. 12, 768 (2021).

Amaya, T. et al. Anisotropic electron transport properties in sumanene crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 408–409 (2009).

Lu, X. et al. Bowl-shaped carbon nanobelts showing size-dependent properties and selective encapsulation of C70. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5934–5941 (2019).

Qiu, Z.-L. et al. Synthesis and interlayer assembly of a graphenic bowl with peripheral selenium annulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3289–3293 (2023).

Butler, K. T., Frost, J. M. & Walsh, A. Ferroelectric materials for solar energy conversion: photoferroics revisited. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 838–848 (2015).

Horiuchi, S. et al. Above-room-temperature ferroelectricity in a single-component molecular crystal. Nature 463, 789–793 (2010).

Miyajima, D. et al. Ferroelectric columnar liquid crystal featuring confined polar groups within core-shell architecture. Science 336, 209–213 (2012).

Tayi, A. S. et al. Room-temperature ferroelectricity in supramolecular networks of charge-transfer complexes. Nature 488, 485–489 (2012).

Vijayaraghaven, R. K., Meskers, S. C. J., Rahim, M. A. & Das, S. Bulk photovoltaic effect in an organic polar crystal. Chem. Commun. 50, 6530–6533 (2014).

Kono, H. et al. Methylene-bridged [6]-, [8]-, and [10]cycloparaphenylenes: size-dependent properties and paratropic belt currents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8939–8946 (2023).

Iwamoto, T., Watanabe, Y., Sakamoto, Y., Suzuki, T. & Yamago, S. Selective and random syntheses of [n]Cycloparaphenylenes (n = 8–13) and size dependence of their electronic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8354–8361 (2011).

Segawa, Y. et al. Combined experimental and theoretical studies on the photophysical properties of cycloparaphenylenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 10, 5979–5984 (2012).

Yang, S.-Y. et al. Circularly polarized thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters in through-space charge transfer on asymmetric spiro skeletons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17756–17765 (2020).

Fujitsuka, M. et al. Properties of triplet-excited [n]cycloparaphenylenes (n = 8–12): excitation energies lower than those of linear oligomers and polymers. J. Phys. Chem. A 118, 4527–4532 (2014).

Ghosh, P. et al. Decoupling excitons from high-frequency vibrations in organic molecules. Nature 629, 355–362 (2024).

Seo, S. E. et al. Recent advances in materials for and applications of triplet–triplet annihilation-based upconversion. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 4483–4496 (2022).

Nishimura, K. et al. Materials chemistry of triplet dynamic nuclear polarization. Chem. Commun. 56, 7217–7232 (2020).

Lu, D. et al. A cycloparaphenylene nanoring with graphenic hexabenzocoronene sidewalls. Chem. Commun. 52, 7164–7167 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Takahiro Sasamori (Tsukuba University), Associate Prof. Yasutomo Segawa (Institute for Molecular Science), Prof. Atsushi Wakamiya (Kyoto University), Assistant Prof. Hiroshi Ueno (Tohoku University), Assistant Prof. Rie Suizu (Nagoya University), Lecturer Yoshiaki Shuku (Nagoya University), Dr. Nobuhiko Mitoma (RIKEN), and Mr. Motonobu Kuwayama (RIKEN) for their helpful comments. We also thank Mr. Tomoki Kato (Nagoya University), Mr. Takato Mori (Nagoya University), Ms. Yuko Otsubo (Nagoya University), and Ms. Yume Saito (Nagoya University) for their help with the experiments. We thank Dr. Riichi Miyamoto (Kyoto University) and Assist. Prof. Kazuyoshi Kanamori (Kyoto University) for collaboration with rapid purification of compounds by using a monolith column. JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers 19H05463 to K.I.) and JSPS Promotion of Joint International Research (grant number 22K21346 to A.Y.) for financial support. H.Sh. thanks the Nagoya University Graduate Program of Transformative Chem-Bio Research (WISE Program) supported by MEXT and the JSPS Fellowship for Young Scientists and Nagoya University Interdisciplinary Frontier Fellowship. Computations were performed using the resources of the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (23-IMS-C087, 24-IMS-C123). This work was also funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through projects IRTG 2678-437785492 and 519972808.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Sh., B.J.R., A.Y., and K.I. conceived the concept. K.I. directed the project. H.Sh. synthesized compounds 1 and 2 and performed DFT calculations. H.Sh. performed X-ray crystallography. H.Sh., K.M., and D.I. performed the photophysical measurements. H.Sh., K.M. and N.K. analyzed the photophysical properties of 1 and 2. D.I. performed electrochemical measurements. P.W. and H.M. performed STM measurements. E.K. and S.A. performed the periodic DFT calculations and STM simulations on the metal substrates. H.Sh. and H.Sa. performed the XRD measurements. H.Sh. and H.K. measured the evaporation temperature without molecular decomposition. H.Sh., A.Y., and K.I. wrote the manuscript with feedback from other authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Han-Yuan Gong and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shudo, H., Wiesener, P., Kolodzeiski, E. et al. Thiophene-fused aromatic belts. Nat Commun 16, 1074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55896-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55896-w

This article is cited by

-

Customized cycloparaphenylene skeletons prepared via the intramolecular coupling of extended biphen[n]arenes

Nature Synthesis (2026)

-

New macrocyclic arenes and beyond: synthesis, properties and applications

Science China Chemistry (2025)