Abstract

The precise placement of thioester bonds into sequence-controlled polymers remains a grand challenge. Here, we demonstrate the versatile synthesis of sequence-controlled polymers from the step polymerization of cyclic thioanhydrides (A), diacrylates (B), and diols/diamines (C). In addition to easily accessible diverse monomers, the method is metal-free/catalyst-free, atom-economical, and wide in monomer scope, yielding 107 polymers with >90% yields and weight-average molecular weights of up to 175.4 kDa. The obtained polymers contain ABAC-type repeating units and precisely distributed in-chain thioester and ester (and amide) groups. The chemoselectivity of the polymerization is revealed by density functional theory calculations. The polymer library exhibits considerably tunable performance: glass-transition temperatures of −36–72 °C, melting temperatures of 43–133 °C, degradability, thermoplastics/elastomers, and thioester-based functions. This study furnishes a facile method to precisely incorporate thioester bonds into sequence-controlled polymers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thioester (O = C–S) bonds are ubiquitous units in biology as they play a significant role in biological systems1,2,3. As an example, acetyl coenzyme A is a thioester that participates in the metabolism of cellular components by virtue of the highly reactive thioacetyl group4. Thioesters are also widely present in many cosmetics, antibiotics, foods, and natural products, which act as valuable building blocks in synthetic chemistry5,6,7. Inspired by the feature of thioesters in nature, researchers have pay widespread attention to thioester-functionalized polymers, resulting in wide applications such as responsive materials, biological conjunctions, and degradable materials8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

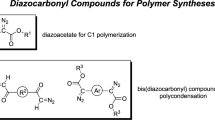

Current methods for the synthesis of poly(thioester)s, however, mainly rely on the polycondensation of dicarboxylic acids and dithiols, suffering from unpleasant odor of dithiols, energy intensive, and the release of water byproduct (Fig. 1a)19,20. Another typical route is the radical polymerization of acrylics and vinyls containing pendant thioester groups (Fig. 1b)21,22. Ring-opening polymerization (ROP) or copolymerization (ROCOP) of thioester-containing cyclic monomers is a more general method for the synthesis of poly(thioester)s (Fig. 1c)23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Recent elegant research has designed a variety of intricately structured monomers for the latter two methods. Despite such progress, the synthesis of such monomers usually requires time-consuming and labor-intensive multiple steps. Furthermore, the regulation of polymer structure and properties is limited due to less monomer diversity. Developing facile and versatile method for the synthesis of poly(thioester)s is highly desirable, yet remains challenging.

a Polycondensation of dithiols and dicarboxylic acids. b Representative monomers for the synthesis of polymers containing side-chain thioester groups. c Representative cyclic thioester-containing monomers for ROP or ROCOP to synthesize poly(thioester)s. d This work: step polymerization of cyclic thioanhydrides, diacrylates, and diols (or diamines).

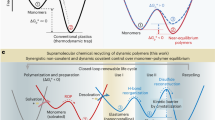

Sequence-controlled polymers containing highly ordered multiple monomer units in a polymer chain have attracted widespread attention40,41. Inspired from nature like DNA, well-defined monomer sequences in synthetic polymers may deliver applications such as data storage, catalysis, and nanoelectronics42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. The obvious method for synthesizing sequence-controlled polymers is to link diverse monomers one by one using iterative chemical steps56,57,58, however, requires much time and effort to attain high-MW polymers. Another feasible method is through monomers containing a predesigned sequence59,60,61, however, usually requires inefficient monomer synthesis. The direct polymerization of various monomers in one step is the simplest method to prepare sequence-controlled polymers62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71, but is still rare. The precise incorporation of thioester bonds into sequence-controlled polymers is even rarer.

Here, we report the step polymerization of cyclic thioanhydrides (A), diacrylates (B), and diols (or diamines, C). The method yields 107 polymers containing ABAC-type units and precisely distributed in-chain thioester bonds. The polymers have widely tuned structure and properties owing to their structural diversity. In addition to easily accessible monomers, the method is nearly quantitative yield, atom-economy, and metal-free/catalyst-free.

Results

We first studied the kinetics of the step polymerization of cyclic thioanhydrides, diacrylates, and diols by the in-situ infrared (IR) spectrometer (Figs. S7–S10). The in-situ IR instrument can display the FT-IR spectra of the reaction mixture in real time, thus revealing the composition and monitoring the polymerization process. The monomers used include 1,10-decanediol, 1,10-decanediol diacrylate, and succinic thioanhydride (Fig. 2a). The common organobase of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) was used as the catalyst. With a molar ratio of [diol]0:[diacrylate]0:[thioanhydride]0:[DBU] =50:50:100:1, the polymerization was run at 90 °C without solvent. The evident peak at 1735 cm−1 in the IR spectrum of the obtained polymer is ascribed to the in-chain C = O bond, which is absence in the IR spectra of the monomers (Fig. S7). As shown in the stacked in-situ IR profile (Fig. 2b), the peak at 1735 cm−1 grows rapidly and reaches almost equilibrium within 90 min (Fig. 2c). The obtained polymer contains in-chain thioester bonds and ABAC-type repeating units, as determined by the NMR spectra (Figs. S13 and S14). By contrast, under the same conditions, the direct step-polymerization of 1,10-decanediol and 1,10-decanediol diacrylate was failed.

a Multicomponent polymerization of 1,10-decanediol, 1,10-decanediol diacrylate, and succinic thioanhydride for the synthesis of P2. b Time-dependent 3D stack plot of the in-situ IR spectra of the polymerization. c Time-dependent peak intensity at 1735 cm−1 in-situ IR profile. d Free energies associated with the coupling of ethanol, succinic thioanhydride, and methyl acrylate.

Then, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to investigate the polymerization mechanism (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Information). We selected the addition of succinic thioanhydride, ethanol, and methyl acrylate as a model reaction. First, the oxygen anion (S1, 1.63 kcal mol−1) generated from the DBU-catalyzed deprotonation nucleophilic attacks the carbonyl group of succinic thioanhydride via TS1 with a barrier of 18.44 kcal mol−1, yielding the thioester anion of S2 (−3.61 kcal mol−1). Then, the thioester anion nucleophilic attacks the C = C bond of methyl acrylate through TS2 with a barrier of 15.67 kcal mol−1, affording the negatively charged intermediate of S3 (5.22 kcal mol−1). Finally, the protons are transferred to S3, yielding the final three-component addition product of S4 (−12.2 kcal mol−1). As a control, the direct addition of ethanol to methyl acrylate requires a higher barrier of 31.06 kcal mol−1. Thus, the coupling reaction of thioanhydride, alcohol, and acrylate undergoes cascade Michael additions with chemoselectivity.

After understanding the polymerization kinetics and mechanism, we extended the polymerization method to a variety of monomers. The monomers used include 13 diols, 9 diacrylates, and 3 cyclic thioanhydrides. The common diols and diacrylates are commercially available and are used as purchased without purification. The cyclic thioanhydrides are synthesized by a simple method: reacting sodium sulfide with related cyclic anhydrides (Figs. S1–S6)72. The obtained cyclic thioanhydrides are sublimated twice for purification before use for polymerization. The cyclic thioanhydrides used are solids and do not release the unpleasant odor that sulfides often carry. The optimized polymerization conditions include: [diol]0:[diacrylate]0:[thioanhydride]0:[DBU] = 50:50:100:1, at 90 °C, for 12 h (Table S1). By the versatile method, we prepared polymers of P1 to P36 having weight-average molecular weight (Mw) of 8.6–47.5 kDa and polydispersity (Đ) of 1.6–2.3, as determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Fig. 3 and Table S2). In step polymerization, the feeding ratio of functional groups has a great influence on the molecular weight of the obtained polymer. The difference in the Mw is mainly attributed to the monomer purity and the feed error. To obtain high-Mw polymers, pure monomers and accurate feeding ratios are necessary. These polymers incorporate ABAC-type repeating units containing precisely distributed in-chain thioester bonds, as revealed by the NMR spectra (Figs. S11–S82). Owing to the step-growth polymerization mechanism, the yields of the polymers are >90%, as determined by the weighing method. Additionally, the obtained polymers are metal-free and colorless and have high solubility in organic solvents like THF, CH2Cl2, and DMF.

These polymers demonstrate widely tunable properties owing to their structural diversity. The polymers exhibit high thermal stability with high decomposition temperatures (Td,5%) of 222–342 °C, as determined by thermogravimetric analysis (Figs. 4a and S242–S313). The thermal stability of these polymers is generally negatively correlated with the density of in-chain easy-to-break carbon-heteroatom bonds. For instance, as illustrated in Fig. 4a, the polymers (P1 to P5 and P10 to P14) with x ≥ 9 and y ≥ 9 present high Td,5% of > 300 °C. The polymers containing in-chain long-carbon chains (P1 to P5, P10 to P14) or oxamide groups (P6 to P8, P15 to P18) are semi-crystalline. The polymers with long-carbon chains are analogous to linear polyethylene incorporating a low density of in-chain thioester and ester groups73. The in-chain oxamide groups can provide hydrogen bonding of polymers. These polymers show melting temperatures (Tm) of 43–98 °C, as determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Figs. 4b and S242–S313). The Tm values are related not only to the carbon number (x) of diamines and the carbon number (y) of diacrylates, but also to the presence of hydrogen bonding. For example, P10 to P14 exhibit gradually increasing Tm (43, 44, 55, 62, and 66 °C). P7 and P8 exhibit higher Tm (95 °C and 98 °C) compared to P4 and P5 (65 °C and 70 °C) (Fig. 4c). Also, the crystallinities of the polymers are confirmed by the wide-angle X-ray scattering diffraction (WAXD, Figs. S456 and S457). By tensile stress-strain experiments, the specimens of semi-crystalline P7 (Tm = 95 °C) show the ultimate tensile strength (σB) of 25.0 MPa and the elongation at break (ɛΒ) of 34% (Fig. S460). Other obtained polymers are amorphous and show a broad range of glass-transition temperatures (Tg) ranging from −29 to 72 °C (Figs. 4c and S242–S313).

Owing to the incorporation of massive in-chain ester and thioester bond, the polymers are easy to degrade under alkaline conditions. We examined the alkalysis of the P2 (1.0 g) in a methanol solution of sodium hydroxide (0.35 M). The polymer was completely degraded at 60 °C for 12 h (Supplementary Information). After simple purification, we obtained 0.49 g (97% yield) of 1,10-diol and 0.82 g (97% yield) of the mixture of sodium mercaptocarboxylate and sodium dicarboxylate (Figs. 4d and S497–S500).

We then sought to improve the mechanical and thermal properties of the polymers by introducing in-chain amide groups that can provide hydrogen bonding of polymers. The step polymerization of di-primary amines, diacrylates, and cyclic thioanhydrides was achieved in the absence of catalysts, owing to the strong nucleophilicity of amines. The polymerization kinetics was monitored using the in-situ IR spectrometer. The selected monomers include 1,3-bis(aminopropyl)tetramethyldisiloxane, 1,10-decanediol diacrylate, and succinic thioanhydride (Fig. 5a). With a molar ratio of [diamine]0:[diacrylate]0:[thioanhydride]0 = 1:1:2, the polymerization was run at 60 °C without solvent. The peak at 1735 cm−1 attributed to the C = O bond of the resulting polymer increases rapidly and reaches near equilibrium in 60 min, as shown in the stacked in-situ IR profile (Fig. 5b, c). The obtained polymer in 120 min has an Mw of 52.6 kDa, suggesting a rapid manner of the polymerization. The polymer contains precisely distributed thioester, ester, and amide groups in repeating units, as determined by the NMR spectra (Figs. S133 and S134). By contrast, under the same conditions, the direct step-polymerization of 1,3-bis(3-aminopropyl)tetramethyl disiloxane and 1,10-decanediol diacrylate yielded the insoluble cross-linked polymer, reaching near equilibrium in 90 min (Figs. S9 and S10). We propose that the crosslinked polymer is formed through a Michael addition mechanism, wherein the primary amine reacts with the acrylate to generate a secondary amine, which subsequently undergoes a second Michael addition with another acrylate moiety, leading to the formation of the crosslinked network.

a Step polymerization of 1,3-bis(aminopropyl)tetramethyldisiloxane, 1,10-decanediol diacrylate, and succinic thioanhydride for the synthesis of P62. b Time-dependent 3D stack plot of the in-situ IR spectra of the polymerization. c Time-dependent peak intensity at 1735 cm−1 in-situ IR profile. d Free energies associated with the coupling of n-butylamine, succinic thioanhydride, and methyl acrylate.

The DFT calculations were also run to study the polymerization mechanism and selectivity (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Information). The addition reaction of succinic thioanhydride, n-butylamine, and methyl acrylate was selected as a model reaction. The primary amine nucleophilic attacks the carbonyl group of succinic thioanhydride via TS1’ with a barrier of 14.30 kcal mol−1, affording the thioacid of S1’ (4.26 kcal mol−1). The deprotonation of S1’ generates the thioester anion of S2’ (−10.92 kcal mol−1). The thioester anion then nucleophilic attacks the C = C bond of methyl acrylate through TS2’ with a barrier of 9.62 kcal mol−1, yielding the negatively charged intermediate of S3’ (8.29 kcal mol−1). The final product of S4’ (−18.98 kcal mol−1) is generated by the transfer of protons. As a control, the direct addition of n-butylamine to methyl acrylate requires a higher barrier of 19.48 kcal mol−1. Therefore, the cascade Michael additions lead to the coupling reaction with chemoselectivity. Additionally, the use of amines for the coupling reaction requires a lower activation energy (14.30 vs. 18.44 kcal mol−1) than the use of alcohols by comparing energy files in Figs. 2d and 5d. These calculations are consistent with the experimental results that the amine-based polymers generally exhibit higher Mw than the alcohol-based polymers. The experimental results are caused by the nucleophilicity of amines being much higher than that of alcohol.

We then extended the versatile polymerization method to 6 di-primary amines, 7 diacrylates, and 2 cyclic thioanhydrides. The optimized polymerization conditions include: [diamine]0:[diacrylate]0:[thioanhydride]0 = 1:1:2, at 60 or 90 °C for 2 h, and DMF as a solvent (Table S3). Generally, the solubility of these polymers in organic solvents is lower than that of polymers synthesized from diols, possibly due to the interaction of hydrogen bonds. DMF with strong solubility is therefore selected as the solvent for the polymerization of diamines, diacrylate, and cyclic thioanhydrides. The method yielded 71 polymers of P37 to P107 with Mw of 25.1–175.4 kDa and Đ of 1.2–2.5 (Fig. 6 and Table S4). The multimodal GPC curves of the polymers are mainly due to the heterogeneity of the system during the polymerization process. These polymers possess ABAC-type units containing precisely distributed in-chain thioester, ester, and amide groups, as determined by the NMR spectra (Figs. S83–S224). Combining kinetics results and DFT calculations, we can get the conclusion that the method presented in this study leads to well-defined sequence-controlled polymers.

Owing to the incorporation in-chain amide groups, the obtained polymers demonstrate improved thermal and mechanical properties. The obtained polymers (P37 to P107) show high Td,5% of 241–305 °C (Figs. S314–S455). The polymers (P51, P52, P56 to P71, P86 to P88, P91 to P106) are amorphous, which were synthesized from diamines bearing flexible chain or large steric hindrance including 1,3-bis(3-aminopropyl)tetramethyl disiloxane, 1,2-bis (2-aminoethoxy) ethane, and isophoron diamine. These amorphous polymers exhibit Tg ranging from −36 to 44 °C (Figs. 7a and S314–S455). The large steric hindrance of diamine leads to higher Tg (> 0 °C) of the polymers. Additionally, due to the presence of hydrogen bonding that acts as physical crosslinking points, some of the amorphous polymers are thermoplastic elastomers (Figs. S470–S479, S488–S490, and S493–S495). For instance, the cyclic tensile testing curves of P93 were demonstrated in Fig. 7b. The P93 specimens were stretched to the maximum elongation of 200%, then released to 0% at 10 mm min−1. A total of 10 cycles were performed without delay between stretching and releasing cycles. The recovery rates [(ɛmax- ɛresidual) ɛmax−1] was calculated as 99% in ten cycles. Other obtained polymers are semi-crystalline with Tm of 64–133 °C (Figs. 7c and S314–S455). The crystallinities of the polymers are also confirmed by the WAXD patterns (Figs. S458 and S459). Some of the semi-crystalline polymers exhibit good mechanical properties (Figs. S461–S469, S480–S487, and S496). As an example, the specimens of P90 prepared by melt processing demonstrate the σB of 25.7 MPa and the ɛΒ of 832% (Fig. 7d).

We also provided some computational evidence on the influence of hydrogen bonding on the thermal properties of the polymers. P47 was selected as a representative case. The corresponding diamine was replaced with a diol containing an identical alkyl chain, yielding polymer P47-1. DSC analysis revealed that the Tg of P47 (−11 °C) is higher than that of P47-1 (−36 °C) (Fig. S507). Also, P47 exhibits a Tm of 100 °C while P47-1 exhibits no Tm. To further explore this phenomenon, molecular dynamics simulations of P47 and P47-1 were performed using the GROMACS software package (2018). Balancing computational efficiency with accuracy, 10 polymer chains, each comprising 9 ABAC repeating units, were placed in a 4 × 4 × 4 nm³ simulation box. Following energy minimization, annealing was conducted from 700 K to 200 K at a rate of 10 K/ns, employing the GAFF force field and excluding polymer chain decomposition. The simulations identified Tm of 419.5 K for P47 and 395.5 K for P47-1 (Fig. S508). This difference suggests stronger intermolecular interactions in P47. To quantify these interactions, additional simulations were carried out under NPT ensembles at 297 K for 20 ns. The analysis decomposed interactions into Coulombic (Coul-SR) and van der Waals (LJ-SR) contributions. As illustrated in Fig. S509, van der Waals forces dominate in both polymers; however, total intermolecular interactions are stronger in P47 compared to P47-1. For P47, the strongest interaction occurred between chains r6 and r7 (−984.89 kJ/mol; Coulomb: −256.27 kJ/mol, VdW: −728.62 kJ/mol), whereas for P47-1, it was between chains r3 and r7 (−669.15 kJ/mol; Coulomb: −118.11 kJ/mol, VdW: −551.04 kJ/mol). Crucially, the interaction regions highlighted significant differences: while P47-1 exhibited ester group interactions, P47 displayed pronounced hydrogen bonding. The stability and persistence of hydrogen bonding in P47 further explain its superior Tg /Tm and enhanced intermolecular interactions (Fig. S510).

In conclusion, we have reported a facile and versatile method to precisely incorporate thioester bonds into sequence-controlled polymers. The step polymerization of cyclic thioanhydride, diacrylates, and diols/diamines features easily accessible monomers, metal-free/catalyst-free, atom-economical, and wide monomer scopes. Using diverse monomers, the polymerization yields 107 polymers with >90% yields and Mw as high as 175.4 kDa. The rapid polymerization kinetics is monitored by the in-situ IR spectrometer. The polymerization mechanism and selectivity are revealed by DFT calculations of the model reaction. The library of polymers incorporates ABAC-type units and precisely distributed thioester and ester (and amide) groups. These polymers manifest a wide range of desirable and tunable properties: Td,5% > 220TGA °C, Tg of −36–72 °C, Tm of 43–133 °C, degradability, thermoplastics and elastomers, and thioester-given functions. This study provides a versatile method to synthesize a library of thioester-containing sequence-controlled polymers, which could attract general interests from researchers in polymer chemistry and materials science.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were used as received without further purification. 1,5-Pentamethylene glycol diacrylate (97%), 2,5-furandimethanol (98%), and sodium trifluoroacetate (97%) were purchased from Aladdin. 1,4-Butylene glycol diacrylate (90%), neopentyl glycol diacrylate (89%), 1,6-hexamethylene glycol diacrylate (85%), 1,9-nonamethylene glycol diacrylate (98%), 1,10-decamethylene glycol diacrylate (90%), diethylene glycol diacrylate (75%), tetraethylene glycol diacrylate (90%), 1,4-benzenedimethanol (99%), isosorbide (98%), 1,6-hexylenediamine (99%), 1,7-diaminoheptane (98%), isophorondiamine (99%), N,N’-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)oxamide (98%), and DBU (98%) were purchased from TCI. 1,3-Bis(3-aminopropyl)tetramethyldisiloxane (97%), 1,10-decanediamine (97%), 1,8-diamino-3,6-dioxaoctane (98%), and DMF (99.8%, Super Dry) were purchased from J&K Chemical. Succinic anhydride (98%), glutaric anhydride (98%), and phthalic anhydride (99%) were purchased from Macklin. Sodium hydroxide (96%), dichloromethane (99%), ethanol (99%), methanol (99%), trichloromethane (99%), methyl tert-butyl ether (99%), tetrahydrofuran, hydrochloric acid (~36%), sodium sulfide nonahydrate (98%), and anhydrous magnesium sulfate (98%) were purchased from SCR.

Characterization and processing techniques

1H and 13C NMR spectra were performed on a Bruker Advance DMX 400 MHz. And chemical shift values were referenced to the signal of the solvent (residual proton resonances for 1H NMR spectra, carbon resonances for 13C NMR spectra).

Infrared spectra of polymer samples were recorded on Nicolet iS20 attenuated total reflection spectrometer.

The Mw and Đ of polymers (P37 to P107) were determined by a DSC equipment composed of Waters 1515 isocratic HPLC pump, Waters 2414 refractive index detector, Waters 2707 autosampler and Styragel series columns (HR3, HR4 and HR5, MW between 500 and 4,000,000). DMF (containing 0.05 mol/L of dry LiBr) was employed as eluent with a flow rate of 1 mL/min at 60 °C. Commercial polystyrenes were used as the calibration standards.

The Mw and Đ of polymers (P1 to P36 with poor solubility in DMF) were determined by a DSC equipment composed of Waters 1515 isocratic HPLC pump, Waters 2414 refractive index detector, Waters 2707 autosampler and Styragel series columns (HR1, HR2 and HR4, MW between 100 and 600,000). THF was employed as eluent with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Commercial polystyrenes were used as the calibration standards.

The Td of the polymers were determined by using TA Q50 instrument. The sample was heated from 40 to 600 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen atmosphere. Temperature when the mass loss is five percent was taken as Td,5%.

DSC measurements of polymers were carried out on a TA Q200 instrument with a heating/cooling rate of 10 °C/min. Data reported are from second heating cycles.

WAXS diffractograms were recorded on a Rigaku Utima IV instrument.

Tensile tests were performed on an Instron 3343 instrument at a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min on compression-moulded tensile testing specimens. Extension to break tests were performed with three replicates per material to report average values and standard deviations for each set.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and its Supplementary information files). All other data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Liu, R. & Orgel, L. E. Oxidative acylation using thioacids. Nature 389, 52–54 (1997).

Huber, C. & Wächtershäuser, G. Peptides by activation of amino acids with CO on (Ni,Fe)S surfaces: implications for the origin of life. Science 281, 670–672 (1998).

Frenkel-Pinter, M. et al. Thioesters provide a plausible prebiotic path to proto-peptides. Nat. Commun. 13, 2569 (2022).

Keefe, A. D., Newton, G. L. & Miller, S. L. A possible prebiotic synthesis of pantetheine, a precursor to coenzyme A. Nature 373, 683–685 (1995).

Ai, H.-J., Lu, W. & Wu, X.-F. Ligand-controlled regiodivergent thiocarbonylation of alkynes toward linear and branched α,β-unsaturated thioesters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17178–17184 (2021).

Tang, H. et al. Direct synthesis of thioesters from feedstock chemicals and elemental sulfur. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5846–5854 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Electrochemical reductive cross-coupling of acyl chlorides and sulfinic acids towards the synthesis of thioesters. Green. Chem. 24, 7350–7354 (2022).

Aksakal, S., Aksakal, R. & Becer, C. R. Thioester functional polymers. Polym. Chem. 9, 4507–4516 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Easy access to diverse multiblock copolymers with on-demand blocks via thioester-relayed in-chain cascade copolymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216685 (2023).

Li, H., Guillaume, S. M. & Carpentier, J.-F. Polythioesters prepared by ring-opening polymerization of cyclic thioesters and related monomers. Chem. – Asian J. 17, e202200641 (2022).

Ivanchenko, O., Mazières, S., Harrisson, S. & Destarac, M. On-demand degradation of thioester/thioketal functions in vinyl pivalate-derived copolymers with thionolactones. Macromolecules 56, 4163–4171 (2023).

Mavila, S., Culver, H. R., Anderson, A. J., Prieto, T. R. & Bowman, C. N. Athermal, chemically triggered release of RNA from thioester nucleic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202110741 (2022).

Yue, T.-J., Ren, W.-M. & Lu, X.-B. Copolymerization involving sulfur-containing monomers. Chem. Rev. 123, 14038 (2023).

Cheng-Jian, Z. & Xing-Hong, Z. Recent progress on COS-derived polymers. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 37, 1–8 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. Productive exchange of thiols and thioesters to form dynamic polythioester-based polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 7, 1312–1316 (2018).

Lütke-Eversloh, T. et al. Biosynthesis of novel thermoplastic polythioesters by engineered Escherichia coli. Nat. Mater. 1, 236–240 (2002).

Xiong, W. & Lu, H. Recyclable polythioesters and polydisulfides with near-equilibrium thermodynamics and dynamic covalent bonds. Sci. China Chem. 66, 725–738 (2023).

Xia, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, Y., Liu, S. & Zhang, X. From oxygenated monomers to well-defined low-carbon polymers. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 108860 (2023).

Kricheldorf, H. R. & Schwarz, G. Poly(thioester)s. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A 44, 625–649 (2007).

Woodhouse, A. W., Kocaarslan, A., Garden, J. A. & Mutlu, H. Unlocking the potential of polythioesters. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 45, 2400260 (2024).

Hadjichristidis, N., Touloupis, C. & Fetters, L. J. Solution properties and chain flexibility of poly(thiolmethacrylates). 2. Poly(cyclohexyl thiolmethacrylate). Macromolecules 14, 128–130 (1981).

Reinicke, S., Espeel, P., Stamenović, M. M. & Du Prez, F. E. Synthesis of multi-functionalized hydrogels by a thiolactone-based synthetic protocol. Polym. Chem. 5, 5461–5470 (2014).

Smith, R. A., Fu, G., McAteer, O., Xu, M. & Gutekunst, W. R. Radical approach to thioester-containing polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1446–1451 (2019).

Yuan, J. et al. 4-Hydroxyproline-derived sustainable polythioesters: controlled ring-opening polymerization, complete recyclability, and facile functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4928–4935 (2019).

Yue, T.-J. et al. Precise synthesis of poly(thioester)s with diverse structures by copolymerization of cyclic thioanhydrides and episulfides mediated by organic ammonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 131, 628–633 (2019).

Han, K. et al. Cyclic thioanhydride/episulfide copolymerizations catalyzed by bipyridine-bisphenolate aluminum/onium pair: approach to structurally and functionally diverse poly(thioester)s. Polym. Chem. 15, 2502–2512 (2024).

Mavila, S. et al. Dynamic and responsive DNA-like polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13594–13598 (2018).

Shi, C. et al. High-performance pan-tactic polythioesters with intrinsic crystallinity and chemical recyclability. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc0495 (2020).

Yuan, P., Sun, Y., Xu, X., Luo, Y. & Hong, M. Towards high-performance sustainable polymers via isomerization-driven irreversible ring-opening polymerization of five-membered thionolactones. Nat. Chem. 14, 294 (2022).

Wang, Y., Li, M., Chen, J., Tao, Y. & Wang, X. O-to-S substitution enables dovetailing conflicting cyclizability, polymerizability, and recyclability: dithiolactone vs. dilactone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 22547–22553 (2021).

Li, H., Ollivier, J., Guillaume, S. M. & Carpentier, J.-F. Tacticity control of cyclic poly(3-Thiobutyrate) prepared by ring-opening polymerization of racemic β-thiobutyrolactone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202386 (2022).

Bannin, T. J. & Kiesewetter, M. K. Poly(thioester) by organocatalytic ring-opening polymerization. Macromolecules 48, 5481–5486 (2015).

Li, K. et al. Kinetic resolution polymerization enabled chemical synthesis of perfectly isotactic polythioesters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202405382 (2024).

Fornacon-Wood, C. et al. Precise construction of weather-sensitive poly(ester-alt-thioesters) from phthalic thioanhydride and oxetane. Chem. Commun. 59, 11353–11356 (2023).

Silbernagl, D., Sturm, H. & Plajer, A. J. Thioanhydride/isothiocyanate/epoxide ring-opening terpolymerisation: sequence selective enchainment of monomer mixtures and switchable catalysis. Polym. Chem. 13, 3981–3985 (2022).

Lyu, C.-Y., Xiong, W., Chen, E.-Q. & Lu, H. Structure-property relationship analysis of D-penicillamine-derived β-polythioesters with varied alkyl side groups. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 41, 1555–1562 (2023).

Zhou, L., Reilly, L. T., Shi, C., Quinn, E. C. & Chen, E. Y. X. Proton-triggered topological transformation in superbase-mediated selective polymerization enables access to ultrahigh-molar-mass cyclic polymers. Nat. Chem. 16, 1357 (2024).

Dai, J. et al. A facile approach towards high-performance poly(thioether-thioester)s with full recyclability. Sci. China Chem. 66, 251–258 (2023).

Stellmach, K. A. et al. Modulating polymerization thermodynamics of thiolactones through substituent and heteroatom incorporation. ACS Macro Lett. 11, 895–901 (2022).

Lutz, J.-F., Ouchi, M., Liu, D. R. & Sawamoto, M. Sequence-controlled polymers. Science 341, 628 (2013).

Milnes, P. J., O’Reilly, R. K. DNA-templated chemistries for sequence controlled oligomer synthesis. In Sequence-Controlled Polymers: Synthesis, Self-Assembly, and Properties, (eds Lutz, J.-F. Meyer, T. Y. Ouchi, M. & Sawamoto, M.) Vol. 1170, 71–84 (ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society, 2014).

McKee, M. L. et al. Multistep DNA-templated reactions for the synthesis of functional sequence controlled oligomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 7948–7951 (2010).

Lewandowski, B. et al. Sequence-specific peptide synthesis by an artificial small-molecule machine. Science 339, 189–193 (2013).

Meier, M. A. R. & Barner-Kowollik, C. A new class of materials: sequence-defined macromolecules and their emerging applications. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806027 (2019).

Yang, C., Wu, K. B., Deng, Y., Yuan, J. & Niu, J. Geared toward applications: a perspective on functional sequence-controlled polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 10, 243–257 (2021).

Wei, J., Xu, L., Wu, W.-H., Sun, F. & Zhang, W.-B. Genetically engineered materials: proteins and beyond. Sci. China Chem. 65, 486–496 (2022).

Matsubara, Y. J. & Kaneko, K. Kinetic selection of template polymer with complex sequences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 118101 (2018).

Webb, M. A., Jackson, N. E., Gil, P. S. & de Pablo, J. J. Targeted sequence design within the coarse-grained polymer genome. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc6216 (2020).

Szweda, R., Tschopp, M., Felix, O., Decher, G. & Lutz, J.-F. Sequences of sequences: spatial organization of coded matter through layer-by-layer assembly of digital polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 15817–15821 (2018).

Szymański, J. K., Abul-Haija, Y. M. & Cronin, L. Exploring strategies to bias sequence in natural and synthetic oligomers and polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 649–658 (2018).

Chen, C. et al. Precision anisotropic brush polymers by sequence controlled chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 1332–1340 (2020).

Dhiman, M. et al. Selective duplex formation in mixed sequence libraries of synthetic polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9326–9334 (2024).

Maron, E. et al. Learning from peptides to access functional precision polymer sequences. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 10747–10751 (2019).

Zhao, W. et al. Lewis pair catalyzed regioselective polymerization of (E,E)-Alkyl sorbates for the synthesis of (AB) sequenced polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24306–24311 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Sequence-mandated, distinct assembly of giant molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15014–15019 (2017).

Mejia, G., Wang, Y., Huang, Z., Shi, Q. & Zhang, Z. Maleimide chemistry: enabling the precision polymer synthesis. Chin. J. Chem. 39, 3177–3187 (2021).

Dong, R. et al. Sequence-defined multifunctional polyethers via liquid-phase synthesis with molecular sieving. Nat. Chem. 11, 136–145 (2019).

Yu, L., Zhang, Z., You, Y.-Z. & Hong, C.-Y. Synthesis of sequence-controlled polymers via sequential thiol-ene and amino-yne click reactions in one pot. Eur. Polym. J. 103, 80–87 (2018).

Gutekunst, W. R. & Hawker, C. J. A general approach to sequence-controlled polymers using macrocyclic ring opening metathesis polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8038–8041 (2015).

Yu, Z., Wang, M., Chen, X.-M., Huang, S. & Yang, H. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of a macrobicyclic olefin bearing a sacrificial silyloxide bridge. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202112526 (2022).

Nowalk, J. A. et al. Sequence-controlled polymers through entropy-driven ring-opening metathesis polymerization: theory, molecular weight control, and monomer design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5741–5752 (2019).

Song, B., Lu, D., Qin, A. & Tang, B. Z. Combining Hydroxyl-Yne and thiol-ene click reactions to facilely access sequence-defined macromolecules for high-density data storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1672–1680 (2022).

Romain, C. et al. Chemoselective polymerizations from mixtures of epoxide, lactone, anhydride, and carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4120–4131 (2016).

Antonopoulou, M.-N. et al. Concurrent control over sequence and dispersity in multiblock copolymers. Nat. Chem. 14, 304–312 (2022).

Hu, C., Pang, X. & Chen, X. Self-switchable polymerization: a smart approach to sequence-controlled degradable copolymers. Macromolecules 55, 1879–1893 (2022).

Xia, X. et al. Multidimensional control of repeating unit/sequence/topology for one-step synthesis of block polymers from monomer mixtures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17905–17915 (2022).

Wang, X., Huo, Z., Xie, X., Shanaiah, N. & Tong, R. Recent advances in sequence-controlled ring-opening copolymerizations of monomer mixtures. Chem. – Asian J. 18, e202201147 (2023).

Jia, Z. et al. Isotactic-alternating, heterotactic-alternating, and ABAA-type sequence-controlled copolyester syntheses via highly stereoselective and regioselective ring-opening polymerization of cyclic diesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4421–4432 (2021).

Bai, Y., Wang, H., He, J. & Zhang, Y. Rapid and scalable access to sequence-controlled DHDM multiblock copolymers by FLP polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 11613–11619 (2020).

Chen, K., Zhou, Y., Han, S., Liu, Y. & Chen, M. Main-chain fluoropolymers with alternating sequence control via light-driven reversible-deactivation copolymerization in batch and flow. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202116135 (2022).

Gao, T. et al. Toward fully controllable monomers sequence: binary organocatalyzed polymerization from Epoxide/Aziridine/Cyclic anhydride monomer mixture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 10.1021/jacs.4c08009 (2024).

Schlessinger, R. H. & Ponticello, I. S. Cyclic thioanhydrides: potentially versatile functional-groups in organic synthesis. J. Chem. Soc. D: Chem. Commun. 1013b−1014b https://doi.org/10.1039/C2969001013B (1969).

Stempfle, F., Ortmann, P. & Mecking, S. Long-chain aliphatic polymers to bridge the gap between semicrystalline polyolefins and traditional polycondensates. Chem. Rev. 116, 4597–4641 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [223B2119 (received by Yanni Xia), U23A2083 (received by Xinghong Zhang), 52373014 (received by Chengjian Zhang), 52203129 (received by Chengjian Zhang)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yanni Xia carried out most of experiments and analysis and wrote the draft. Tong Shao carried out the analysis of polymerization mechanism. Yue Sun, Jianuo Wang, and Chaoyuan Gu carried out the analysis of polymer structure. Chengjian Zhang conceived, designed, and directed the investigation and revised the manuscript. Xinghong Zhang conceived and directed the investigation and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Moritz Kränzlein and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, Y., Shao, T., Sun, Y. et al. Precise placement of thioester bonds into sequence-controlled polymers containing ABAC-type units. Nat Commun 16, 1974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57208-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57208-8

This article is cited by

-

Ring-opening Polymerization of Benzo-fused Thiolactones toward Chemically Recyclable Semi-aromatic Polythioesters

Chinese Journal of Polymer Science (2025)