Abstract

Zeolite-confined metal is an important class of heterogeneous catalysts, demonstrating exceptional catalytic performance in many reactions, but the identification of a stable metal-zeolite combination with a simple synthetic method remains a top challenge. Here artificial intelligence methods, particularly global neural network potential based large-scale atomic simulation, are utilized to design Pt-containing zeolite frameworks for propane-to-propene conversion. We show that out of the zeolite database (>220 structure framework) and more than 100,000 Pt/Ge differently distributed configurations, there are only three Ge-containing zeolites, germanosilicate (MFI, IWW and SAO) that are predicted to be capable of stabilizing Pt single atom embedded in zeolite skeleton and at the meantime allowing propane fast diffusion. Among, the Pt1@Ge-MFI catalyst is successfully synthesized via a simple one-pot synthesis without a lengthy post-treatment procedure, and characterized by high-resolution experimental techniques. We demonstrate that the catalyst features an in-situ formed [GePtO3H2] active site under the reductive reaction condition that can achieve long-term (>750 h) high activity and selectivity (98%) for propane dehydrogenation. Our simple catalyst synthesis holds promise for scale-up industrial applications that can now be rooted in first principles via data-driven catalyst design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zeolite-confined metal (metal@zeolite) catalysts have attracted persistent attention over the past 60 years for the zeolite’s unique functionality in dispersing and stabilizing metals within zeolite micropores1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In the propane dehydrogenation (PDH) reaction8, a high-temperature (e.g., 873 K) reaction suffering from severe deactivation by the coking and sintering in traditional metal catalysts9,10, it has been proven that encapsulating active metals within zeolite is an effective strategy to prolong catalyst lifespans, as evidenced in Pt@Fe-MWW (10 h reported for PDH)11, K-PtSn@MFI (70 h)12, Pt@Ge-UTL(4500 h)13, and RhIn@MFI (5500 h)14. Despite these impressive progresses, the high cost of catalyst materials (e.g., UTL and Rh) and the sophisticated catalyst synthesis procedure remain the main obstacles towards low-cost industrialization. It is thus highly desirable to develop new methods for designing economic and facilely synthesizable metal@zeolite PDH catalysts.

To date, metal@zeolite catalysts were often synthesized using the one-pot method12,15,16, but followed by a multi-step catalyst activation procedure, which was believed to activate and stabilize the catalysts for working at high temperatures. For example, K-PtSn@MFI and Pt@Fe-MWW catalysts11,12, both synthesized via the hydrothermal crystallization, were then treated by air calcination and H2 reduction, which, however, were still not stable enough during the PDH conversion (<70 h). The Pt@Ge-UTL catalyst, while showing exceptionally long stability and high activity13, involved a lengthy synthesis process, including the synthesis of a special organic structure directing agent (OSDA) ((6R, 10S)-6, 10-dimethyl-5-azoniaspiro decane hydroxide), the crystallization, the calcination, the Pt impregnation, and the acid pickling. While it is practically important to develop simple synthetic methods to prepare metal@zeolite catalysts with high stability and activity, such a goal is frustrated even at the right beginning: due to the complex structure of metal@zeolite catalysts and limited available literature data, it is essentially unknown for what kind of metal-zeolite combination is potentially stable enough to survive under the high-temperature PDH conversion. Apparently, with over 220 types of zeolite framework available and a number of possible second-metal promoters (e.g., Sn, Fe, Ge, and In), the trial-and-error experiments by testing every likely combination are prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

With the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, recent years have seen AI applications in resolving the reaction active sites, screening the material properties, and narrowing the experimental scope in both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis17,18,19,20,21,22. In particular, we recently established zeolite databases by using global neural network potential (G-NN) structure search followed by density functional theory (DFT) validation, which provided a fast description of zeolite geometry and acidic properties23,24. These AI techniques and zeolite databases opened a promising route toward streamlining zeolite catalyst screening.

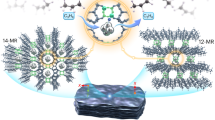

Here, with the aid of G-NN-based atomic simulation, we propose a hierarchy strategy to screen thousands of Pt-embedded (Ge)-zeolite systems, from which only three germanosilicate zeolites (MFI, IWW, and SAO) were identified that were capable of stabilizing Pt single atoms in zeolite skeleton with the help of Ge and at the meantime allowed fast propane diffusion. This designed catalyst was synthesized via a simple one-pot synthetic approach without any post-treatment in the MFI framework. The catalyst was reduced in situ under PDH conditions, forming the [GePtO3H2] active site, which demonstrated superior long-term stability, catalytic activity, and selectivity for PDH.

Results and discussion

Our investigation began with the theoretical screening of Pt-doped silicate zeolite (Zeo[SiO2]) and germanosilicate zeolite (Zeo[GeSiO2]) for PDH reaction, where Ge acted as the second-metal promoter to better stabilize Pt. To achieve this, we proposed five criteria for germanosilicate zeolite skeleton screening. Two criteria were set first from the geometric dimension to allow the fast screening. First, the zeolite channel diameter needed to exceed the dynamic diameters of propane and propene molecules (size from 3.8 to 4 Å) to allow their diffusion25. Thus, a channel diameter greater than 4 Å was utilized to ensure unimpeded diffusion of propane in at least two dimensions. Second, the intersection of the channels needed to form a larger cavity that could hold subnanometric Pt clusters and terminate their growth. This intersection cavity could scavenge freely diffusing Pt atoms/several-atom clusters in channels as found from our previous work26, which, when trapped in the cavity, remained active and stable for the PDH reaction13,27. The diameter of this scavenger cage was restricted to not exceeding 1 nm.

Three energetic criteria were then designed to conduct more precise screening, which is now enabled by large-scale global neural network potential-based global optimization, as implemented in large-scale atomic simulation with neural network potential (LASP) code24,28,29.

Specifically, third, the zeolites with both pure silica and germanosilicate frameworks should be stable. Our previous work proved that zeolites with cage structures are, in general, more stable than a double-layer (DL) SiO2 phase, but less stable than the densely packed quartz phase. The SiO2 DL phase, being 0.18 eV per f.u. above quartz, thus dictates the upper energy bound of any SiO2 zeolite structure23,30, serving as a practical benchmark for assessing the stability of pure silica composition. When incorporating the Ge element into the zeolite framework, we could design a replacement energy metric (ΔErep) to quantify the energy change arising from the substitution of one Si atom in the pure silica zeolite framework by Ge(OH)4, resulting in the formation of germanosilicate zeolite and Si(OH)4, as illustrated in Eq. (1), where all germanosilicate zeolite structures are the most stable structures by exploring all possibilities of the substitution of Si by Ge. Based on the structure of more than thirty synthesized SiGe zeolites known in experiments, we determined that a threshold of 0.35 eV for ΔErep as a thermodynamics descriptor to screen the feasibility of Ge replacement in the experiment, where 90% of experimentally synthesized SiGe zeolites have ΔErep values less than 0.35 eV (also see Fig. S1 and Table S1).

Fourth, the Ge element must provide extra stabilization to Pt. Considering that Pt after reduction could exist as either single atoms (Pt1) or small clusters (e.g., Pt4), we measured the stabilizing effect of Ge on Pt in both forms. The relative stability energy metrics, ΔEPt1 and ΔEPt4, are utilized to assess the energy change of the Pt single atom and Pt cluster moving close to the Ge site in the zeolite framework, respectively, as shown in Eqs. (2) and (3). Obviously, the negative ΔEPt1 or ΔEPt4 is desirable, indicating that Ge can stabilize Pt. To prevent Pt segregation, our goal is to maximally stabilize Pt single atoms, not Pt clusters, and thus we will screen germanosilicate zeolites with negative ΔEPt1 (ΔEPt1 < 0) but positive ΔEPt4 (ΔEPt4 > 0) (also see Fig. S2 and Table S1).

Figure 1a depicts the results of the zeolite skeleton screening process based on the aforementioned criteria. From over 220 synthesized zeolite skeletons with more than 100,000 differently distributed Ge and Pt configurations explored by LASP (Table S1), we identified only 3 (MFI, IWW, and SAO) zeolites that met all the criteria to stabilize the Pt single atom. Among three zeolites, SAO zeolite is difficult to synthesize: a recent synthesis of SAO zeolite, involving a non-commercial N,N′-diethylbicyclo[2.2.2]oct-7-ene-2,3:5,6-dipyrrolidine as OSDA, suggests a prohibitive cost to industrialization31. Similarly, the synthesis of IWW zeolite also requires a large OSDA molecule, e.g., 1,4-bis-(dimethyl-1-adamantylammonium)-butane. Our preliminary synthetic tests indicated that it is not straightforward to encapsulate Pt into IWW zeolite because ethylenediamine (EDA) molecules commonly utilized to protect Pt source interfere with the zeolite crystallization, leading to poorly crystallized material other than IWW zeolite (see Fig. S3). By contrast, the synthesis of MFI zeolite with a large volume of experimental literatures is facile and has a low cost32,33,34,35,36,37. Furthermore, the EDA introduced with Pt source can even act as the OSDA of MFI zeolite38. We thus select MFI as a candidate for further catalysis experiments.

Moreover, we performed long-time (2 ns) molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for the predicted [Pt–O–Ge]@MFI structure at 823 K in the Nose-Hoover canonic ensemble to assess its stability. We found that the [Pt–O–Ge] unit was stable and Pt did not leach out from the framework, as shown by the Pt trajectory during MD that was found to be tightly localized near the Ge site (see Fig. S4). Therefore, both thermodynamics catalyst screening and MD kinetic results suggested the tendency to form a highly stable [Pt–O–Ge] pattern inside the MFI framework, which could be a promising active site for PDH reaction.

Synthesis and characterization of Pt1@Ge-MFI

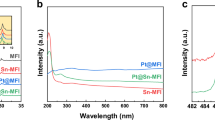

Guided by theoretical predictions, we then conducted experiments to synthesize and characterize Pt-embedded germanosilicate MFI zeolite catalysts. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, we adopted the simple one-pot method to obtain the catalyst by simultaneously mixing the Si and Ge sources, the OSDA, and the Pt precursor solution in a Teflon-lined autoclave that underwent the hydrothermal crystallization for 96 hours. This as-synthesized catalyst denoted as Pt@Ge-MFI(r), was transferred into the reaction tube directly for pre-reduction and PDH catalytic testing. To characterize the working catalyst under reaction conditions, we treated Pt@Ge-MFI(r) with 30 sccm H2 flow at 873 K for 4 h in a tube furnace that was then cooled down to ambient temperature, and the obtained catalyst was referred to as Pt@Ge-MFI. For comparison, the traditional way of metal@zeolite catalyst synthesis that was subjected to post-treatment procedures was also tested. Specifically, the product obtained via solvothermal synthesis was first oxidized in air at 873 K for 4 h in a muffle furnace, followed by 4 hours’ H2 reduction in a tubular furnace, denoted as Pt@Ge-MFI-c. Furthermore, a control catalyst without Ge doping was synthesized using the same procedure as Pt@Ge-MFI, and was referred to as Pt@MFI. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of these Ge-MFI samples were found to be the same as that of Mutinaite (PDF #44-0002), proving the formation of MFI-type zeolite (Fig. 2b). Additionally, the zeolite framework demonstrated structural stability under both reduction conditions and reaction conditions (Fig. S5). The Pt content in these samples was controlled to be ~0.3 wt%, a typical value used in other PDH catalysts12,13,27. The Ge:Pt ratio is 30.8, which secured enough Ge sites available to capture Pt atoms in the skeleton (Fig. S6). The atomic ratio contents of the samples can be found in Table S2.

a Scheme to show the synthesis procedures of Pt@Ge-MFI and Pt@Ge-MFI-c. b XRD patterns of Pt@Ge-MFI(r) (as-synthesized raw sample), Pt@Ge-MFI (as-synthesized catalyst after H2 reduction) and Pt@Ge-MFI-c (as-synthesized catalyst subject to air calcination and H2 reduction). The standard pattern of Mutinaite (PDF#44-0002) is shown for comparison. c–f TEM images of Pt@Ge-MFI (c, d) and Pt@Ge-MFI-c (e, f). g The Pt 4f XPS spectra of Pt@Ge-MFI and Pt@Ge-MFI-c, along with the corresponding EDS images where O, Si, Ge, and Pt are highlighted in pink, green, blue, and red, respectively. The XPS binding energy was calibrated using C 1s at 284.8 eV. In the EDS mapping, large Pt clusters adhering to the zeolite surface are highlighted by circles. h Pt L3-edge normalized XANES spectra of Pt@Ge-MFI, Pt@Ge-MFI-c, Pt foil and PtO2 obtained from synchrotron experiments. i Pt L3-edge radial distance χ(R) space spectra of Pt@Ge-MFI, Pt@Ge-MFI-c, Pt foil and PtO2. More details of χ(k) space spectra fitting curves are shown in Fig. S6 and Table S3. All labels denoted as “a.u.” in Fig. 2 reprensent “arbitrary units”.

We characterized the Pt@Ge-MFI catalyst using different techniques, including high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Specifically, HR-TEM and SEM images revealed a uniform dispersion of Pt without visible clusters (see Fig. 2c, d and SEM images in Fig. S7a–f). The low peak intensity in XPS spectra indicated that Pt was highly dispersed within the zeolite bulk, making it undetectable by the surface-sensitive XPS technique (Fig. 2g). The Pt L3-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectrum of Pt@Ge-MFI indicated that the oxidation state of Pt lay between +2 and +4, displaying a slightly reduced white line intensity compared to the PtO2 (Fig. 2h). Furthermore, the real-space Pt L3-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectrum from XAS showed a prominent peak at 1.98 Å (Fig. 2i), attributed to the Pt–O bond, with EXAFS fitting analysis yielding a Pt–O coordination number (CN) of 3.4 ± 0.7 (Table S3). The same conclusion on the Pt coordination environment in Pt@Ge-MFI could be drawn by wavelet EXAFS spectrum and χ(k) space spectra fitting curve (Figs. S8c and S9c). Collectively, these characterizations led us to conclude that Pt in Pt@Ge-MFI existed as single atoms occupying T-atom sites in the zeolite framework, resulting in a high Pt valence state and a significant Pt–O coordination number. A similar conclusion was also reported by Deng et al. regarding Pt single atoms in the Y zeolite matrix39,40.

Different from the Pt@Ge-MFI sample, the calcined Pt@Ge-MFI-c sample showed the formation of Pt clusters. The HR-TEM images (Fig. 2e, f) and SEM images (Fig. S10c, d) clearly showed the formation of Pt clusters adhering to the zeolite surface. This observation was further corroborated by XPS results (Fig. 2g), which indicated the presence of zero-valent Pt. Additionally, the white line intensity and peak position in the XANES spectrum of Pt@Ge-MFI-c closely matched that of Pt foil (Fig. 2h), indicating the presence of a metallic Pt state. The EXAFS analysis (Fig. 2i) of the Pt L3-edge radial distance χ(R) spectrum revealed a strong Pt–Pt bonding peak at around 2.81 Å, with a coordination number (CN) of 10.0 (Table S3), confirming the formation of Pt metal clusters. Similarly, the wavelet EXAFS spectrum and the χ(k) space spectra fitting curve of Pt@Ge-MFI-c (Figs. S8d and S9d) revealed the presence of Pt–Pt bonds. These Pt clusters should form primarily after the high-temperature calcination by comparing with SEM images of the sample without reduction (Fig. S10a, b). In fact, our in-situ XRD proved that the Pt (111) peak appeared as early as 773 K during calcination (Fig. S11), whereas no Pt (111) peak was observed throughout the reduction process of Pt@Ge-MFI(r) (Fig. S12). This indicated that the air calcination procedure led to the formation of Pt clusters, suggesting the Ge stabilization to Pt was destroyed under the high-temperature oxidative conditions.

Catalytic performance of Pt@Ge-MFI and kinetic studies

The catalytic performances in propane dehydrogenation (PDH) reactions for three catalysts were then evaluated in the fixed-bed reactor under the condition of WHSVpropane = 1.75 h−1, propane/N2 = 1/3, reaction temperature = 873 K and atmospheric pressure. In a typical run, a certain amount of sample was loaded into a quartz tube and pretreated in pure H2 (30 sccm) for 4 h at the reaction temperature, followed by complete removal of H2 with N2. Figure 3a shows the results of three different catalysts.

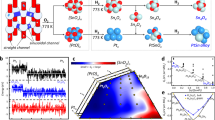

a The catalytic performance of Pt@Ge-MFI, Pt@Ge-MFI-c, and Pt@MFI. The PDH reaction is carried out under the conditions of WHSVpropane = 1.75 h−1, propane/N2 = 1/3, 873 K, and atmospheric pressure. b The long-term catalytic performance of Pt@Ge-MFI under various conditions as detailed in the Figure. c Arrhenius plot in the temperature range from 803 K to 843 K, with the violin plot of ln(k) value distribution under different temperatures.

For the Pt@MFI catalyst without Ge doping, although the selectivity reached 90% in the beginning, the catalyst suffered a serious quick deactivation. The initial propane conversion rate was 32% and then decreased to 1% after 120 min, with the deactivation constant kd of 1.05 h−1 in 2 h. With the Ge doping, the deactivation was suppressed appreciably for both Pt@Ge-MFI and Pt@Ge-MFI-c catalysts. It proved that the presence of Ge always enhanced the stability no matter the forms of Pt, either an embedded Pt single atom or Pt clusters, which was consistent with the results of the Wu group where Pt was in clusters13.

More importantly, we noted that the Pt existing as a single atom was much more stable than that of the cluster. For the calcined sample, the Pt@Ge-MFI-c catalyst, the initial propane conversion rate was 55% and then decreased to 24% after 720 min. However, the PDH reaction catalyzed by Pt@Ge-MFI maintained a high propane conversion rate of 60% (near the reaction thermodynamic equilibrium) and a high selectivity of >96% in a long reaction period (12 h in Fig. 3a and ~120 h in Fig. S13). Its kd was 8.3 × 10−4 h−1, two orders of magnitude lower than that of Pt@Ge-MFI-c catalyst with kd of 0.11 h−1. After the reaction, we found that most Pt single atoms still maintained the original form in the spent Pt@Ge-MFI catalyst, as characterized by SEM images (Fig. S7g–i), TEM images (Fig. S14a, b), and XPS spectra (Fig. S15). The trace of Pt clusters formed at the high reduction temperature did appear to terminate after the initial growth, which was attributed to our scavenger strategy by the intersection cavity (Fig. 1). By contrast, the poisoning cokes formed quickly in the Pt@Ge-MFI-c catalyst according to TEM images of spent Pt@Ge-MFI-c (Fig. S14c, d), which could be attributed to the carbon-chain-growth on large Pt clusters.

To evaluate the long-term PDH conversion performance, we tested the Pt@Ge-MFI catalyst under various reaction conditions over 750 h of reaction. As shown in Fig. 3b, regardless of changes in propane gas pressure or temperature, the catalyst maintained a near-equilibrium conversion rate and a high propene selectivity exceeding 95% at a low weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 5 h−1. Although increasing the WHSV slightly reduced propane conversion due to gas diffusion restrictions, this issue might be addressed in the future by reducing the grain size of the MFI zeolite and engineering the scale-up reactor. It is noteworthy that under conditions of 823 K with pure propane and a WHSV of 5 h−1 Pt@Ge-MFI achieved equilibrium conversion (28%), despite an initial selectivity of 95% that remained steady at 98%, highlighting the catalyst’s robustness and stability under demanding reaction conditions. Overall, the Pt@Ge-MFI catalyst, featuring the simple one-pot synthesis method, the high propane conversion, the high propene selectivity, and excellent reaction stability, held great potential for low-cost industrial applications.

In-situ active site and the reaction mechanism

Finally, we were in the position to elucidate the reaction active site and the PDH reaction mechanisms on Pt@Ge-MFI catalyst. The experimental kinetic tests showed that the apparent activation energy (Ea) was approximately 0.46 eV (Fig. 3c) with the detailed catalytic performance shown in Fig. S16. At the 823 K, the total reaction rate was 23.8 mmol/gcat, which corresponded to a total energy barrier of 2.20 eV, assuming that the pre-exponential factor in the Arrhenius equation was 1.08 × 1014 obtained from kBT/ħ. Combining this with the first-order reaction kinetics of PDH with respect to propane pressure reported in the literature41, we calculated the Gibbs free energy change for propane adsorption at 823 K to be 1.74 eV. This translated to a propane adsorption energy of −0.27 eV at 0 K, indicating that propane underwent weak physical adsorption on the catalyst.

Next, DFT calculations were performed to determine the in-situ active site structure under the reaction condition. We found that the Pt atom near the Ge with the formation of [Pt–O–Ge] configuration was 0.19 eV more stable than that of the Pt single atom far from the Ge. More importantly, the initial Pt–O–Ge structure, [GeOPtO3], could be readily reduced by H2. The removal of oxygen atom from the [GeOPtO3] configuration by H2 was highly favorable, leading to a [GePtO3] structure with the Gibbs free energy change being −1.32 eV at 873 K (Fig. 4a). This [GePtO3] structure could further react with an additional H2 molecule: after H2 dissociatively adsorbed onto this site, a [GePtO3H2] structure was formed with two hydroxyl groups formed near the Pt site. This process was also thermodynamically favorable, with a Gibbs free energy change of −0.88 eV (Fig. 4a). At this moment, the Pt was reduced to near Pt0 with the Bader charge of +0.26 |e|, quite smaller than that of Pt in [GeOPtO3] and [GePtO3] forms with the Bader charge of +1.31 and +0.87 |e−|. It is worth noting that this process was thermodynamically reversible under air conditions. The presence of O2 facilitated the reaction of adsorbed hydrogen to form water and further fill the oxygen vacancy with Gibbs free energies of −0.41 eV and −1.27 eV at 300 K, respectively. This explained why the ex situ EXAFS results pointed to a high Pt–O coordination number of 3.4.

a Thermodynamics of the active site reconstruction at 823 K during the reaction and at 300 K ambient condition. b CO-IR spectra of Pt@Ge-MFI and the theoretical computed IR, where the “expt.” and “theo.” refer to the results obtained from experiments and theoretical calculations. c Gibbs free energy profiles for propane dehydrogenation pathways on a [GePtO3H2] active site. d Atomic structure snapshots showing the key reaction intermediates in (c).

It might be mentioned that the presence of Ge allowed oxygen removal near Pt (exothermic by 1.32 eV), which freed the coordination of Pt and thus allowed the subsequent PDH reaction to occur at the Pt site. For comparison, in the silica zeolite without Ge, the O removal at the [Pt–O-Si] unit was exothermic only by 0.1 eV in Gibbs free energy (Fig. S17), which reflected the strong Si–O bond in pure silica. Considering that Pt preferred to stay near Ge as [Pt–O–Ge] in MFI (ΔEPt1 < 0, Fig. 1), the presence of Ge facilitated the formation of a more stable low-valent Pt site.

The existence of Pt was confirmed through the in-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy of CO adsorption (CO-DRIFT). The Pt@Ge-MFI sample was pre-treated in a flow of 30 sccm H2 at 673 K for one hour and then exposed under 10 sccm CO flow before being purged with He. The CO-DRIFT spectrum of Pt@Ge-MFI-c showed a dominant peak at 2046 cm−1 and a minor peak at 2077 cm−1, which were typically assigned to linearly adsorbed CO on large Pt clusters13,42 and small Pt nanoparticles, respectively13,43,44. While, the CO-DRIFT spectrum of Pt@Ge-MFI showed a dominant peak at 2123 cm−1, which was assigned to CO on Ptδ+ sites as reported by many groups43,45,46. Our DFT calculation results showed that the vibration frequency for CO adsorbed on [GePtO3] site with the valence state of Pt of near +2 was 2119 cm−1, closely aligning with our experimental results, further confirming the presence of Pt single atom in zeolite skeleton.

Considering that the [GePtO3] site could be further reduced by H2 to form the [GePtO3H2] site under the reaction condition, we therefore explored the reaction mechanism of PDH reaction on [GePtO3H2] site by DFT and the free energy reaction profile under 823 K was shown in Fig. 4c, together with the snapshots of key reaction transition state (TS) in Fig. 4d. The reaction started by propane adsorption on Pt1@Ge-MFI with [GePtO3H2] structure, which was endothermic by 1.77 eV in free energy (exothermic by 0.24 eV in 0 K) due to the large entropy loss at reaction condition 823 K. The adsorbed propane underwent the β-C–H bond cleavage, forming CH3CHCH3 and H species, which attached to the Pt and O atoms, respectively. The Gibbs free energy barrier for this step was 0.55 eV, and the reaction was exothermic by 1.69 eV. Next, CH3CHCH3 species underwent further α-C–H bond cleavage and the formed propene species and H atom were both bound to the Pt atom. The second C–H bond cleavage had a reaction barrier of 1.03 eV and was exothermic by 0.43 eV. The previous H atom bonded at the near O and then migrated to Pt, with a migration barrier of 1.68 eV, which yielded a six-coordinated Pt (Fig. 4d, C3H6*+2H*). After propene desorption to release 0.75 eV in free energy, the two remaining H atoms on Pt could recombine to form H₂, with a barrier of 2.03 eV. From the reaction profile, we could determine the overall free energy barriers as 2.32 eV (the first step dehydrogenation, see Fig. 4c) and the apparent activation enthalpy as 0.55 eV (reducing the entropy contribution due to the propane adsorption from the overall free energy barrier), which were in good agreements with experimental values of 2.2 eV and 0.46 eV.

Our experimental and theoretical results confirmed that a [GePtO3H2] unit was in-situ generated in the Pt-embedded germanosilicate MFI catalysts, which exhibited superior thermodynamic stability and a high activity to the PDH reaction. Lots of previous literature proves that the active sites for PDH reaction were small Pt clusters47,48,49,50,51,52. Along the guidance, many strategies were proposed to mitigate the strong thermodynamic tendency of Pt cluster growth and thus keep the fine Pt dispersion, e.g., via strong metal-support interactions, Sn alloying, support amorphization, and zeolite confinement27. The zeolite confinement approach might be further benefited by the addition of second elements (such as Sn53,54, Ga55,56, In57,58, and Zn59,60,61) to stabilize Pt clusters by modifying the electronic structure of Pt or providing the anchoring sites, although not all elements (e.g., Al57,62) were effective. While, our results of Pt@Ge-MFI proved that Pt single atom site in zeolite could also exhibit excellent PDH catalytic performance and thus provided a new, atom-economic solution to anchor and disperse single Pt in zeolite. The reaction involved a dynamic catalytic cycle between Pt2+ in [GePtO3] and Pt0 in [GePtO3H2], where Ge in the zeolite skeleton played a key role in coordinating with Pt and stabilizing reaction intermediates. Our data-driven theoretical method proved to be a simple but effective way of identifying the metal-zeolite combination to host the active metal (Pt).

To recap, this work proposed a data-driven catalyst design strategy to search stable metal@zeolite catalysts for PDH reaction. By exploring all zeolite frameworks and more than 100,000 zeolite configuration candidates in the hierarchy screening, we predicted only three germanosilicate zeolites (MFI, IWW, and SAO) that could act as the structure holder to stabilize single Pt atoms for the target reaction. Our catalyst screening took into account both geometrical and energetic factors, including the zeolite channel size, the cavity size, the exothermicity of embedding heteroatoms (Ge) into zeolite and the energetics for single atoms and clusters of active metal (Pt) in zeolite framework, where the key energetic factors could now be assessed by large-scale global neural network based global optimizations.

Guided by theory, we synthesized the single Pt atoms embedded in the germanosilicate MFI zeolite catalysts using a simple one-pot method without any post-treatment procedures. The as-synthesized catalyst was in-situ reduced and shown to exhibit a long-term activity (750 h) with a high selectivity (98%) in PDH conversion. These highly dispersed Pt single atoms were present as a [GePtO3] unit, which could reversibly convert to [GePtO3H2] at the reaction conditions. Our results demonstrated the catalyst design from first principles aiming to configure the active site structure and simplify the synthetic route now feasible, which offered a strong handle to link the fundamental research with scale-up industrial applications.

Methods

G-NN potential and SSW simulations

Our approach for resolving MFI encapsulated Pt cluster structures was based on the stochastic surface walking (SSW) global optimization using G-NN, the SSW-NN method, as implemented in LASP code28. The G-NN potential was generated by iterative self-learning of the plane wave DFT global potential energy surface (PES) dataset generated from SSW-NN exploration. The SSW-NN simulation to explore PES could be divided into three steps: the global PES dataset generation based on DFT calculations using selected structures from SSW global PES exploration, the G-NN potential fitting, and SSW global PES exploration using the G-NN potential. These steps were iteratively performed until the G-NN potential was transferable and robust enough to describe the global PES. The procedure was briefly summarized below.

At first, a global dataset was built iteratively via the self-learning of the global PES. The initial data of the global dataset came from the DFT-based SSW simulation, and all the other data was progressively accumulated from G-NN-based SSW PES exploration. In order to cover all the likely compositions of Pt–Ge–Si–O–H systems, SSW simulations were carried out for different structures (including bulk, layer, and cluster), compositions, and atom numbers per unit cell. Overall, these SSW simulations generated more than 107 structures on PES. The final global dataset that was computed from high-accuracy DFT calculations contained 75,183 structures.

Then, the G-NN potential was generated using the method introduced in our previous work63,64. To pursue a high accuracy for PES, we adopted a many-body-function corrected global NN architecture (G-MBNN), and 474 power-type structure descriptors for each element were utilized to distinguish structures in the global dataset. The neural network consisted of three hidden layers, structured as a 474-80-80-80-8 network, resulting in approximately 250,000 network parameters in total. The final layer with 8 nodes was enveloped into a series of many-body functions, which summed to yield the total energy65.

The min-max scaling was utilized to normalization the training data sets. Hyperbolic tangent activation functions were used for the hidden layers, while a linear transformation was applied to the output layer of all networks. The limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (L-BFGS) method was used to minimize the loss function to match DFT energy, force, and stress. The final energy and force criteria of the root mean square errors for the Pt–Ge–Si–O–H G-NN potential were around 4.0 meV/atom and 0.153 eV/Å, respectively.

With the G-NN potential, we were able to efficiently explore the PES of Pt–Ge–Si–O–H systems. For each zeolite skeleton, we enumerated and calculated all possible T sites for Ge substitution, from which the most stable position for Ge within the framework was identified. We then replaced the Si atoms near the Ge atom with Pt and investigated the possible substitution sites for a single Pt atom. This allowed us to determine the best Pt–O–Ge configuration (Pt1) in the zeolite framework. For the configuration of Pt4 cluster, we introduced the Pt4 cluster into the zeolite channel near the Ge position and explored the structure configurations using SSW-NN. Over 2000 minima were examined for each zeolite framework to determine the most stable configuration of the Pt4 cluster, which ensured the finding of the most stable Pt4 configuration in the presence of Ge. Finally, all the low energy structure candidates from G-NN potential calculations were verified by plane-wave DFT calculations, and thus, the energetic data reported in the work, without specifically mentioning, was from DFT.

DFT calculations

All DFT calculations were performed by using the plane wave VASP code66, where the electron–ion interaction was represented by the projector augmented wave pseudopotential67,68. The exchange-correlation function utilized was the spin-polarized GGA-PBE69. The kinetic energy cutoff was set as 450 eV. The first Brillion zone k-point sampling utilized the 1 × 1 × 1 gamma-centered mesh grid for MFI zeolite. The energy and force criterion for convergence of the electron density and structure optimization were set at 1 × 10−5 eV and 0.05 eV/Å, respectively. The propane dehydrogenation reaction profile was determined by SSW reaction sampling and double-ended surface walking (DESW) transition state search as developed previously70,71.

Catalyst synthesis

The Pt precursor solution was first prepared by mixing 1.2 g H2PtCl6·xH2O, 14 mL EDA, and 160 mL deionized water followed by overnight stirring. Then, 16.48 g tetraethyl orthosilicate, 20 mL deionized water, and 2.332 g germanium oxide were added into 25.98 g tetrapropylammonium solution (25 wt% in water, TPAOH). The resultant solution was stirred for 3 h (500 rpm) at ambient temperature before 8.5 mL Pt precursor solution was added. After 10 min’ stirring, the solution was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave. Afterward, the one-pot hydrothermal synthesis was carried out at 170 °C for 96 h in an electric oven. The as-synthesized raw product, Pt@Ge-MFI(r), obtained by filtration, wash, and overnight drying at 80 °C, was then loaded in the fixed-bed reactor for catalytic tests, where the catalyst was pre-reduced as Pt@Ge-MFI. In the meantime, Pt@Ge-MFI(r) was calcined in a muffle furnace at 873 K for 4 h followed by 4 h’ H2 reduction to make Pt@Ge-MFI-c.

Catalytic test for propane dehydrogenation

The propane dehydrogenation reaction (PDH) was performed with a fixed-bed reactor under atmospheric pressure. Calculated amount of catalyst was loaded in a Ф10 × 2 quartz tube, heated to reaction temperature in N2 with a ramp rate of 10 °C/min and reduced in pure H2 flow (30 sccm). After the reduction pre-treatment, the reaction feed gas (pure propane or a mixture of propane and N2) with varied flow rates was introduced into the reactor. The products were analyzed by online gas chromatography.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the article, the Supplementary Information, and the Source Data file. Also, the germanosilicate zeolites with the most stable configuration for each zeolite skeleton after DFT optimization are shown on the website www.lasphub.com/database/#/zeodopedGe. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The software code of LASP and G-NN potential used within the article is available from the corresponding author upon request or on the website http://www.lasphub.com.

References

Li, X., Yang, X., Huang, Y., Zhang, T. & Liu, B. Supported noble-metal single atoms for heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Mater. 31, e1902031 (2019).

Sharma, G. et al. Novel development of nanoparticles to bimetallic nanoparticles and their composites: a review. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 31, 257–269 (2019).

Xu, H., Shang, H., Wang, C. & Du, Y. Ultrafine Pt-based nanowires for advanced catalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000793 (2020).

Vieira, L. H. H. et al. Noble metals in recent developments of heterogeneous catalysts for CO2 conversion processes. Chemcatchem 15, e202300493 (2023).

Singh, S. A., Varun, Y., Goyal, P., Sreedhar, I. & Madras, G. Feed effects on water-gas shift activity of M/Co3O4-ZrO2 (M = Pt, Pd, and Ru) and potassium role in methane suppression. Catalysts 13, 838 (2023).

Deka, J. R. et al. Carboxylic acid functionalized cage-type mesoporous silica FDU-12 as support for controlled synthesis of platinum nanoparticles and their catalytic applications. Chemistry 24, 13540–13548 (2018).

Chai, Y. et al. Nickel phosphide nanoparticles as a noble-metal-free co-catalyst for the selective photocatalytic aerobic oxidation of CH4 into CO and H2. J. Catal. 425, 306–313 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Bimetallic PtSn nanoparticles confined in hierarchical ZSM-5 for propane dehydrogenation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 41, 384–391 (2022).

Moliner, M. et al. Reversible transformation of Pt nanoparticles into single atoms inside high-silica chabazite zeolite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15743–15750 (2016).

Kunwar, D. et al. Stabilizing high metal loadings of thermally stable platinum single atoms on an industrial catalyst support. ACS Catal. 9, 3978–3990 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Single Pt coordinated with framework Fe in MWW-type ferrisilicate toward efficient propane dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 14, 9431–9439 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Regioselective generation and reactivity control of subnanometric platinum clusters in zeolites for high-temperature catalysis. Nat. Mater. 18, 866 (2019).

Ma, Y. et al. Germanium-enriched double-four-membered-ring units inducing zeolite-confined subnanometric Pt clusters for efficient propane dehydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 6, 506–518 (2023).

Zeng, L. et al. Stable anchoring of single rhodium atoms by indium in zeolite alkane dehydrogenation catalysts. Science 383, 998–1004 (2024).

Bols, M. L. et al. Selective formation of α-Fe(II) Sites on Fe-zeolites through one-pot synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 16243–16255 (2021).

Yan, R. et al. Novel shielding and synergy effects of Mn-Ce oxides confined in mesoporous zeolite for low temperature selective catalytic reduction of NOx with enhanced SO2/H2O tolerance. J. Hazard. Mater. 396, 122592 (2020).

Yang, Z. & Gao, W. Applications of machine learning in alloy catalysts: rational selection and future development of descriptors. Adv. Sci. 9, 2106043 (2022).

Li, H., Jiao, Y., Davey, K. & Qiao, S.-Z. Data-driven machine learning for understanding surface structures of heterogeneous catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216383 (2023).

Hart, G. L. W., Mueller, T., Toher, C. & Curtarolo, S. Machine learning for alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 730–755 (2021).

Mai, H., Le, T. C., Chen, D., Winkler, D. A. & Caruso, R. A. Machine learning for electrocatalyst and photocatalyst design and discovery. Chem. Rev. 122, 13478–13515 (2022).

Zahrt, A. F. et al. Prediction of higher-selectivity catalysts by computer-driven worlflow and machine learning. Science 363, 247 (2019).

Weng, B. et al. Simple descriptor derived from symbolic regression accelerating the discovery of new perovskite catalysts. Nat. Commun. 11, 3513 (2020).

Ma, S. & Liu, Z.-P. Machine learning potential era of zeolite simulation. Chem. Sci. 13, 5055–5068 (2022).

Xie, X.-T. et al. LASP to the future of atomic simulation: intelligence and automation. Precis. Chem. 2, 612–627 (2024).

Combariza, A. F., Sastre, G. & Corma, A. Molecular dynamics simulations of the diffusion of small chain hydrocarbons in 8-ring zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 875–884 (2011).

Ma, S. & Liu, Z.-P. Zeolite-confined subnanometric PtSn mimicking mortise-and-tenon joinery for catalytic propane dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 13, 2716 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Generation of subnanometric platinum with high stability during transformation of a 2D zeolite into 3D. Nat. Mater. 16, 132–138 (2017).

Huang, S.-D., Shang, C., Kang, P.-L., Zhang, X.-J. & Liu, Z.-P. LASP: fast global potential energy surface exploration. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 9, e1415 (2019).

Kang, P.-l, Shang, C. & Liu, Z.-p Recent implementations in LASP 3.0: global neural network potential with multiple elements and better long-range description. Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 34, 583–590 (2021).

Ma, S., Shang, C., Wang, C.-M. & Liu, Z.-P. Thermodynamic rules for zeolite formation from machine learning based global optimization. Chem. Sci. 11, 10113–10118 (2020).

Gonzalez-Camunas, N. et al. Synthesis of the large pore aluminophosphate STA-1 and its application as a catalyst for the Beckmann rearrangement of cyclohexanone oxime. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 15398–15411 (2024).

Hu, Z.-P. et al. Atomic insight into the local structure and microenvironment of isolated Co-motifs in MFI zeolite frameworks for propane dehydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12127–12137 (2022).

Jeon, M. Y. et al. Ultra-selective high-flux membranes from directly synthesized zeolite nanosheets. Nature 543, 690 (2017).

Lee, S., Park, Y. & Choi, M. Cooperative interplay of micropores/mesopores of hierarchical zeolite in chemical production. ACS Catal. 14, 2031–2048 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Product selectivity controlled by nanoporous environments in zeolite crystals enveloping rhodium nanoparticle catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8482–8488 (2019).

Wang, N. et al. In situ confinement of ultrasmall Pd clusters within nanosized silicalite-1 zeolite for highly efficient catalysis of hydrogen generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7484–7487 (2016).

Wang, N. et al. Impregnating subnanometer metallic nanocatalysts into self-pillared zeolite nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6905–6914 (2021).

Abubakar, A. & Abubakar, S. Synthesis and characterization of ZSM-5 zeolite using ethelinediammine as organic template: via hydrothermal process. Fudma J. Sci. 4, 476–480 (2020).

Deng, X. et al. Zeolite-encaged isolated platinum ions enable heterolytic dihydrogen activation and selective hydrogenations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20898–20906 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. Template-guided regioselective encaging of platinum single atoms into Y zeolite: enhanced selectivity in semihydrogenation and resistance to poisoning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205978 (2022).

Sheintuch, M., Liron, O., Ricca, A. & Palma, V. Propane dehydrogenation kinetics on supported Pt catalyst. Appl. Catal. A 516, 17–29 (2016).

Stakheev, A. Y., Shpiro, E. S., Jaeger, N. I. & Schulzekloff, G. Electronic-state and location of Pt metal-clusters in KL zeolite—FTIR study of CO chemisorption. Catal. Lett. 32, 147–158 (1995).

Ding, K. et al. Identification of active sites in CO oxidation and water-gas shift over supported Pt catalysts. Science 350, 189–192 (2015).

Ivanova, E., Mihaylov, M., Thibault-Starzyk, F., Daturi, M. & Hadjiivanov, K. FTIR spectroscopy study of CO and NO adsorption and co-adsorption on Pt/TiO2. J. Mol. Catal. A 274, 179–184 (2007).

Hoang, S. et al. Activating low-temperature diesel oxidation by single-atom Pt on TiO2 nanowire array. Nat. Commun. 11, 1062 (2020).

Zhang, J., Zhu, D., Yan, J. & Wang, C.-A. Strong metal-support interactions induced by an ultrafast laser. Nat. Commun. 12, 6665 (2021).

Hou, W. et al. Highly stable and selective Pt/TS-1 catalysts for the efficient nonoxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145648 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Defect-driven unique stability of Pt/carbon nanotubes for propane dehydrogenation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 464, 146–152 (2019).

Liu, J., Liu, C., Da, Z. & Zheng, H. Phosphorous-modified carbon nanotube-supported Pt nanoparticles for propane dehydrogenation reaction. China Pet. Process. Petrochem. Technol. 21, 7–14 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Origin of the robust catalytic performance of nanodiamond graphene-supported Pt nanoparticles used in the propane dehydrogenation reaction. ACS Catal. 7, 3349–3355 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Framework-confined Sn in Si-beta stabilizing ultra-small Pt nanoclusters as direct propane dehydrogenation catalysts with high selectivity and stability. Catal. Sci. Technol. 9, 6993–7002 (2019).

Zhai, Z. et al. Revealing the promotion of carbonyl groups on vacancy stabilized Pt4/nanocarbons for propane dehydrogenation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 23236–23244 (2022).

Wei, X. et al. Bimetallic clusters confined inside silicalite-1 for stable propane dehydrogenation. Nano Res. 16, 10881–10889 (2023).

Miao, C. et al. Pt-Sn nanoalloys on Sn-Beta zeolite for efficient propane dehydrogenation. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 361, 112736 (2023).

Zhang, B., Zheng, L., Zhai, Z., Li, G. & Liu, G. Subsurface-regulated PtGa nanoparticles confined in silicalite-1 for propane dehydrogenation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 16259–16266 (2021).

Oliveira, A. S. et al. Propane dehydrogenation over Pt and Ga-containing MFI zeolites with modified acidity and textural properties. Catalysis Today 427, 114437 (2024).

Yuan, Y., Huang, E., Hwang, S., Liu, P. & Chen, J. G. Confining platinum clusters in indium-modified ZSM-5 zeolite to promote propane dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6529 (2024).

Luo, L. et al. Close intimacy between PtIn clusters and zeolite channels for ultrastability toward propane dehydrogenation. Nano Lett. 24, 7236–7243 (2024).

Bing, L. et al. Bimetallic PtZn nanoparticles anchored in high-silica SSZ-13 zeolite for efficient propane dehydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. 491, 151961 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. PtZn intermetallic nanoalloy encapsulated in silicalite-1 for propane dehydrogenation. Aiche J. 67, e17295 (2021).

Wang, Y., Hu, Z.-P., Lv, X., Chen, L. & Yuan, Z.-Y. Ultrasmall PtZn bimetallic nanoclusters encapsulated in silicalite-1 zeolite with superior performance for propane dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 385, 61–69 (2020).

Lefton, N. G. & Bell, A. T. Effects of structure on the activity, selectivity, and stability of Pt-Sn-DeAlBEA for propane dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 14, 3986–4000 (2024).

Huang, S.-D., Shang, C., Zhang, X.-J. & Liu, Z.-P. Material discovery by combining stochastic surface walking global optimization with a neural network. Chem. Sci. 8, 6327–6337 (2017).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Kang, P.-L., Yang, Z.-X., Shang, C. & Liu, Z.-P. Global neural network potential with explicit many-body functions for improved descriptions of complex potential energy surface. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 7972–7981 (2023).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244 (1992).

Zhang, X.-J. & Liu, Z.-P. Variable-cell double-ended surface walking method for fast transition state location of solid phase transitions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 4885–4894 (2015).

Zhang, X.-J. & Liu, Z.-P. Reaction sampling and reactivity prediction using the stochastic surface walking method. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 2757–2769 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB1180000), the National Science Foundation of China (12188101, 22422208, 22203101, 22033003), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFA1509600), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20720220011), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (No. 2023265), the Science &Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (23ZR1476100) and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20240272). We would like to express our special thanks to Dr. Kun Lu from the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology for his help in IWW zeolite synthesis. The numerical calculations in this study were partially carried out on the ORISE supercomputer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-P. L. conceived the project and contributed to the design of the calculations and analyses of the data. S. M. carried out most of the calculations and wrote the draft of the paper. Q. Z carried out the calculations, experiments and wrote the draft of the paper. L. C. helped on the experiments. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Florian Goeltl, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, QC., Chen, L., Ma, S. et al. Data-driven discovery of Pt single atom embedded germanosilicate MFI zeolite catalysts for propane dehydrogenation. Nat Commun 16, 3720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58960-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58960-7