Abstract

Plastic film mulching (PM), which contributes to nearly half of the increased crop yields in dryland agroecosystems, exacerbates environmental burdens due to its non-degradable nature. Globally, there is a growing demand to replace non-degradable PM with degradable film mulching (DM), yet its impacts on soil organic carbon (SOC) in dryland agroecosystems remains unknown. Here, using multi-field studies and mesocosm experiments, we found that DM strongly increased but PM reduced SOC storage (0–1 m). This difference is likely attributable to the higher microbial C use efficiency in soil under DM, leading to increased microbial-derived C compared to PM. Under the high roading scenario for 2100, DM could reduce the decomposition of SOC (0–1 m) in China’s drylands by 9.0 ± 1.0 Mg ha–1 year–1 (one standard error) compared with PM. Our findings highlight that DM is a promising alternative to PM for sequestrating SOC and alleviating C loss under climate change in dryland agroecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a key component of global carbon (C) cycling, the sequestration of soil organic C (SOC) plays a critical role in mitigating climate change, enhancing soil fertility, and maintaining ecosystem services1,2. Drylands, which cover 45% of the Earth’s terrestrial area, store ~32% of the global SOC3. In these regions, plastic film mulching (PM)—one of the most effective strategies for enhancing crop yields, expands the area suitable for planting crops. This technique has been implemented in the production of over 40 crops. It is widely adopted worldwide, particularly in China, which accounts for 40% of global agricultural plastic film4,5,6,7. However, its effect on SOC storage is poorly understood, as PM not only promotes root biomass production, which contributes to SOC retention, but also potentially accelerates SOC decomposition by increasing soil temperature and moisture content4,5,6. Another complexity is a globally growing demand to replace traditionally used PM with degradable film mulching (DM), as PM causes ‘white pollution’ due to its degradation-resistant nature and accumulation of microplastics7,8,9,10. The DM may have completely different effects on SOC. Thus, it is crucial to understand how PM and its substitution by DM affect soil C pools and their differential responses to climate change.

Despite considerable scientific research on this topic over the past decades, there is no consensus on the direction and magnitude of PM-driven changes in SOC. Such a result mainly arises from two factors. First is the complexity of the PM system’s impact on SOC by altering both C inputs and outputs from the soil. Second, SOC is characterized as a ‘slow variable’ in Earth system models, with a turnover time spanning several centuries. The inherent complexity of SOC makes it difficult to predict the changes in SOC patterns2,11,12,13,14. Recent evidence indicates that partitioning SOC into plant- and microbial-derived C based on different sources will help to understand the mechanisms associated with the turnover and stability of SOC15,16,17,18. Plant C input functions as an energy source for microorganisms19. Microbial-derived C originates from the ex vivo modification of extracellular enzymes or synthetic metabolites resulting from in vivo turnover15,20,21. Therefore, any effort to optimize management practices for long-term C storage demands a greater understanding of variations in these diverse functionalities and sources of C. In addition, most previous studies on SOC only considered topsoil (up to 0.3 m depth)22,23,24,25. However, how subsoil C storage responds to reductions in C input (such as litter and root biomass) remains uncertain. Ignoring changes in the deep soil C pool, which contains 68% of global SOC, may lead to biased interpretations of the potential impacts of mulching on soil C storage or even result in misleading conclusions26,27. Currently, most research concentrates on the PM system, and no studies have addressed the mechanisms of soil C storage changes under DM. Given the differences in the degradation performances of both film types, PM and DM have varied effects on soil hydrothermal properties, soil aggregate structure, microbial habitat, and substrate availability4,5,8,10. These differences may alter microbial- and plant-derived C through direct pathways (microbial C use efficiency (CUE), C-related functional genes, or soil respiration) or indirect pathways (extracellular enzyme activities (EEAs)). Differences in the function and origin of SOC components might explain these diverse responses, but the potential mechanisms involved remain unclear.

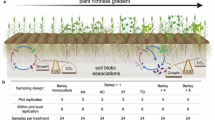

We employ two independent approaches to address these key questions, including multi-site field measurements and continental-scale sampling for mesocosm experiments. First, we monitored the variation in SOC storage (0–1 m) across four arid farmland sites, used two groups of biomarkers comprising amino sugars and lignin phenols to trace microbial- and plant-derived C, respectively17,18,28, and evaluated a range of biotic and abiotic factors that are associated with the responses. Second, we performed a continental-scale sampling (comprising 153 soil columns) across 17 dryland sites (80°45′E–126°38′E) for incubation experiments to quantify the contributions of microbial- and plant-derived C to changes in SOC storage under climate change conditions.

Results

Effects of mulching practices on SOC storage

The SOC storage in the 0–1 m soil decreased by 1.9 Mg ha–1 yr–1 under PM but increased by 0.5 Mg ha–1 yr–1 under DM compared with the conditions before the experiment (Fig. 1a). In the topsoil (0–0.3 m), SOC storage increased by 4.1% (95% confidence interval: 2.6–5.7%) under DM (p < 0.05), while it remained at a similar level under PM. In the subsoil (0.3–1 m), SOC storage decreased by 6.7% (95% confidence interval: 5.8–7.6%) under PM (p < 0.05), while there was little change under DM compared to the start of the experiment (Fig. 1b). Moreover, the SOC content under mulching decreased linearly as the mean annual temperature increased among the different study sites (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Changes in SOC storage at 0–1 m depth under different mulching practices compared with the conditions before the experiment. b SOC storage in the soil profile under different mulching practices. Dots represent mean cumulative storage values based on equivalent soil mass (ESM). Error bars represent standard errors (n = 54). Hollow points indicate no significant difference from pre-treatment conditions (gray dashed line), while solid points represent significant differences (p < 0.05). SOC soil organic carbon, NM conventional tillage without mulching, PM plastic film mulching, DM degradable film mulching. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Changes in SOC derived from microbial and plant sources

Microbial-derived C accounted for 39.3–43.0% of SOC storage, substantially higher than the contribution from plant-derived C (7.2–9.6%) (Fig. 2a and b). The proportion of microbial-derived C in SOC increased with soil depth. In contrast, the contribution from plant-derived C had the opposite trend (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Compared with NM, we observed a statistically significant decrease of 9.6% in microbial-derived C content under PM (p < 0.05), while the microbial-derived C content under DM remained unchanged (Fig. 2c). Both PM and DM increased the plant-derived C content, particularly in the topsoil, with increases of 38.9% under PM (853 mg kg–1) and by 32.3% under DM (710 mg kg–1) compared with NM (Fig. 2d). The increase in SOC was accompanied by an enrichment of amino sugars and a decrease in lignin phenols. In contrast, increased oxidation of plant lignin was common in SOC-rich soils (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

a, b Microbial- and plant-derived C storage at 0–1 m depth under different mulching practices. c, d Microbial- and plant-derived C content in the soil profile under different mulching practices. Error bars represent standard errors (n = 12). NM conventional tillage without mulching, PM plastic film mulching, DM degradable film mulching. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Drivers of microbial- and plant-derived C

Microbial-derived C was significantly influenced by soil hydrothermal conditions and microbial properties, with CUE identified as the most important factor. High CUE facilitated the accumulation of microbial-derived C at all study sites (Fig. 3a and b). Belowground biomass (BEG) was the most significant predictor for plant-derived C, with plant-derived C in the soil increasing with BEG (Fig. 3a and c). We found that biotic and abiotic factors together explained 92% of the variation in SOC pools. Notably, lignin phenols and amino sugars had contrasting direct effects on soil C pools (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Relative importance of variables that affected microbial-derived C. b Relationship between microbial-derived C and CUE. c Relative importance of variables that affected plant-derived C. d Relationship between plant-derived C and BEG. Shadows denote the 95% confidence intervals for the regression lines. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. SWC soil water content, ST soil temperature, ABG aboveground biomass, BEG belowground biomass, CERs annual C emissions from soil respiration, CERh annual C emissions from heterotrophic respiration, CERa annual C emissions from autotrophic respiration, Bacteria bacterial PLFAs, Fungi fungal PLFAs, CUE microbial C use efficiency, Hy-EEAs hydrolytic C-acquiring extracellular enzyme activities, Ox-EEAs oxidative C-acquiring extracellular enzyme activities, YL Yangling, CW Changwu, PY Pengyang, AD Anding, NM conventional tillage without mulching, PM plastic film mulching, DM degradable film mulching. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SOC storage mediated by C-cycling related functional genes

The PM significantly increased the abundance of C degradation genes across various soil depths compared with NM (Fig. 4a). In contrast, DM reduced the abundances of genes involved in chitin (naglu and chiA), pectin (pgu), and lignin (glx, lig, mnp, and pox) decomposition (28.8%, 95% confidence interval: 20.0–37.7%). Both PM and DM enhanced the C fixation capacity in the topsoil. However, in the subsoil, the abundance of C fixation genes was 83.1% (95% confidence interval: 27.7–138.5%) higher under DM than under PM. As the abundance of functional genes related to C degradation increased, the loss of SOC storage increased linearly (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1).The multi-model inference procedure identified a high abundance of abfA and glx as key factors driving declines in soil C storage (Fig. 4c).

a Changes in functional genes involved in C degradation and fixation under PM and DM compared with NM. The spans of whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (n = 12). b Linear mixed-effects models showing the relationship between the abundance of C degradation-related functional genes and dSOC. c The fixed effects of functional gene abundance on dSOC in the optimal model, following Z-transformation of the data and subsequent model screening. SOC soil organic carbon, dSOC SOC storage in farmland minus SOC storage in the previous year, PM plastic film mulching, DM degradable film mulching. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Degradable film mulching decreases C decomposition under climate change

The results of the mesocosm incubation experiments showed that C losses under all treatments were predominantly from microbial-derived C (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 6–8), especially in the subsoil (Fig. 5b). In particular, PM increased the microbial-derived C loss rate in all soil depths, resulting in the highest C loss in the 0–1 m soil depth. In contrast, the SOC loss from the 0–1 m soil depth was 14.3% (1.8 Mg ha–1 yr–1) and 45.1% (9.0 Mg ha–1 yr–1) lower under DM than under NM and PM, respectively. This reduction was largely driven by a 33.1% (1.5 Mg ha–1 yr–1) and 62.1% (5.1 Mg ha–1 yr–1) decrease in microbial-derived C loss from the subsoil (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the microbial- and plant-derived C loss increased linearly as the SOC or clay content increased (Supplementary Fig. 9).

a Spatial distributions of sampling sites and ΔSOC in the topsoil and subsoil under different mulching practices. Error bars represent standard error (n = 3). b Changes in SOC, microbial- and plant-derived C storage during the incubation experiment. Error bars represent half of the standard error, and lowercase letters indicate significant differences at p = 0.05 (n = 51). SOC soil organic carbon, Δmicrobial-derived C soil microbial-derived C in sampling sites before the incubation experiment minus microbial-derived C after the experiment, ΔPlant-derived C soil plant-derived C in sampling sites before the incubation experiment minus plant-derived C after the experiment, ΔSOC SOC in sampling sites before the incubation experiment minus SOC after the experiment, NM conventional tillage without mulching, PM plastic film mulching, DM degradable film mulching. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. The aridity index data used in the figure were obtained from the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database–Version 3 (Global-AI_PET_v3)29.

Discussion

Previous studies generally suggested that PM does not accelerate the loss of SOC22,23,24,25. Our study demonstrated how changes in microbial- and plant-derived C under different mulching practices affected SOC storage (Figs. 1 and 2). We found a significant decline in SOC storage under PM, suggesting that results obtained in previous studies may have been markedly overestimated. At the same time, DM increased soil C storage (Fig. 1a). These findings underscore the potential benefits of replacing PM with DM to improve agricultural soil C sequestration. At least three mechanisms explain the contrasting changes in SOC storage under PM and DM.

First, material properties influence plant-derived C (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 10). In terms of C inputs, DM contributed plant-derived C to the soil at levels comparable to PM (Fig. 2b), and this carbon input is primarily regulated by root biomass. Notably, the mechanical properties of the degradable film gradually deteriorate throughout crop growth until breakdown occurs (Supplementary Fig. 11), significantly reducing its ability to increase the temperature and conserve moisture, which results in lower C decomposition6,14,22. The improvements in the soil temperature conditions under PM catalyze the breakdown of complex macromolecules, allowing microbes to access protected litter or SOC more readily23,29. Under PM, lignin phenols were found to have high (Ad/Al)V and (Ad/Al)S ratios and low C/V and S/V ratios, possibly because the enhanced hydrothermal conditions facilitated the microbial decomposition of plant-derived C (Supplementary Fig. 12). Moreover, the competitive advantage of bacteria under warming conditions resulted in a significant increase in the F/B ratio under PM, further facilitating the decomposition and uptake of plant residues30,31,32. By dividing the soil respiration components, we found that DM reduced C emissions due to heterotrophic respiration by microorganisms (Supplementary Fig. 10). Water availability is a key factor influencing the CO2 flux; increased SWC in arid regions can boost C emissions through direct (microbial activity and root growth) and indirect (soil nutrient availability) pathways33. On the other hand, compared to fully degradable films that break down into starch, CO2, and H2O, polyethylene plastic films may release chemicals that alter CO2 emissions from the surface soil6,34.

Second, the activities and turnover of microorganisms dominate soil C transformation and sequestration processes. Microorganisms have crucial roles in the mineralization process by acting in two key pathways, where they decompose SOC to generate CO2 but also contribute significantly to C sequestration through the formation of microbial biomass and the “entombing effect”15. We found that the low CUE in PM is a major factor contributing to the reduction of microbial-derived C (MDC). The sustained anaerobic environment under PM also promoted soil mineralization and decreased the production and accumulation of microbial-derived C (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 13). Moreover, the microbial-derived C accumulation pattern influenced by the microbial growth, reproduction, and death process could potentially change under the ongoing warming effect of mulching, which was supported by the decrease in MAOC in the present study (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). In particular, PM increased the abundance of microbial functional genes that target the oxidation of recalcitrant C compounds, thereby amplifying microbial-mediated microbial-derived C decomposition35. The significantly reduced G+/G– ratio under PM suggests a decrease in the proportion of recalcitrant C (Supplementary Fig. 16). By contrast, DM slowed the microbial decomposition of recalcitrant C compounds (such as cellulose, chitin, pectin, and lignin), while enhancing C fixation in the subsoil (Fig. 4a). In addition, the growth and turnover rates are faster for r-strategist organisms than k-strategists, thereby leading to a higher yield of microbial residues. Thus, a decline in the ratio of r-strategist relative to k-strategist microorganisms under warming conditions is not conducive to producing microbial-derived C36.

Third, the decreased availability of soil nitrogen (N) caused by mulching altered the EEAs (Supplementary Figs. 17–19). The reduced nitrogen availability under film mulching was due to higher crop biomass, which led to the redistribution of nitrogen from soil to biomass and increased macroaggregate sorption of soil NH4+37. To maintain the stoichiometric balance at the community level, the microorganisms under PM promoted the decomposition of complex phenols and lignin through the increased production of ligninases (oxidases) (Supplementary Fig. 17), which supports the “microbial N mining theory”38,39. This high C cost for acquiring recalcitrant N also explains the lower CUE in the subsoil under PM (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Analysis of the plant and microbial sources of C in soil showed that microbial-derived C was dominant in the soil C pool under all treatments, particularly in the subsoil (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Previous studies highlighted the dominant role of fungal necromass C, where the stability of fungal necromass C was associated with the high CUE exhibited by fungal communities17,40. Moreover, the high sensitivity of fungi to limited fresh litter inputs led to microorganisms decomposing a larger fraction of fungal necromass C in the deep soil to support their reproduction and growth (Supplementary Fig. 21b). This phenomenon is widespread across various ecosystems, including forests, farmlands, and grasslands41,42,43,44. The lower GlcN/MurA ratio under PM implied the instability of microbial-derived C (Supplementary Fig. 21c). Significant shifts in SOC storage were predicted for future stages, primarily due to the considerable impacts of climate change on C stability and C inputs14,45,46. In contrast to the field experiment results, SOC storage under DM showed a declining trend, although C loss was significantly reduced compared to NM and PM (P < 0.05). We observed that the loss of C was primarily driven by microbial-derived C, with PM strongly amplifying the effects of climate change (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Notably, the substantially lower contribution of microbial-derived C to the C pool under PM may indicate alterations in the microbial C pump within the soil15, potentially leading to the loss of stable C that has accumulated over centuries within a relatively brief period. Clearly, restoring this C would be immensely challenging.

Why have previous studies overestimated the C sequestration under PM22,23,24,25,47? Our study reveals that those overestimations were attributable to the rapid depletion of SOC in the subsoil (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15), which was not considered in most previous studies. We propose four possible explanations for this phenomenon. First, the accumulation of SOC was strongly influenced by litter input. PM and DM mitigated the impacts of drought and low temperatures on the productivity of rain-fed farmland, leading to significant increases in net primary productivity (Supplementary Fig. 10). In farmland without external C inputs, the soil C pool is primarily replenished by aboveground litter and root biomass47,48. Thus, the subsoil receives a far lower quantity of organic matter than the topsoil, and this disparity resulted in considerably lower plant-derived C inputs in deep soils under mulching (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2b)49. Second, the abundances of the dominant functional genes associated with C fixation under PM declined significantly in the subsoil (Fig. 4a). Third, PM accelerated the turnover rate of microbial biomass in the deep soil, with turnover time decreasing by one-fifth compared with NM (Supplementary Fig. 22). Finally, the C in the deeper soil may be more sensitive to temperature changes. A soil warming experiment conducted by Soong et al.50 showed that the high sensitivity of subsoil C to temperature led to a significant increase in deep soil CO2 effluxes, with a net loss of SOC storage in the 0.2–0.9 m soil depth.

Admittedly, our study has several limitations. First, the C sequestration benefits of DM should be evaluated more comprehensively across a broader range of regions. Second, during the mesocosm experiments, we could not place soil samples from each site in individual climate chambers to simulate site-specific air temperature. Thus, our study may have overestimated C losses in cold regions under climate change. Finally, despite recent advances in understanding how plant- and microbial-derived C contribute to SOC formation and stabilization, soil remains a complex and heterogeneous environment. Uncertainties persist in the estimates of plant- and microbial-derived C, arising from three key factors: (1) some MAOC formed through abiotic processes are not included in the soil microbial carbon pump model51; (2) the use of fixed conversion factors introduces uncertainty in estimating plant- and microbial-derived C21; and (3) current analytical methods cannot accurately quantify all types of amino sugars and lignin52. Therefore, future research should prioritize developing new biomarkers to comprehensively assess plant- and microbial-derived C and further explore the impact of mineral–microbial interactions on SOC transformation and biotic-abiotic aggregation processes.

In summary, this study reveals consistent trends in the impacts of mulching on soil C storage across the dryland agroecosystems. Specifically, PM reduced C storage, while DM generally increased C storage across soil horizons. Our findings highlight the importance of understanding deep soil C dynamics, given that observing the surface soil alone can lead to substantial overestimates of the beneficial effects of mulching on C storage (Fig. 1b). Moreover, assessing C sources can deepen our understanding of the mechanisms that underlying changes in C sequestration (Fig. 6). PM increased the turnover of microbial-derived C, thereby reducing the available C pools (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 22). In contrast, DM prevented the accelerated degradation of stable C in the subsoil and mitigated dryland C–climate feedback during long-term mulching (Fig. 5). It is important to recognize that adopting and implementing additional strategic measures is crucial for reversing the declining trend in C pools in the context of climate change.

(1) Film mulching alters crop productivity and biomass allocation to subsequently influence soil C inputs. (2) Pathway for microbial in vivo turnover. (3) Pathway for microbial ex vivo modification. (4) Accumulation of microbial-derived C. (5) Accumulation of plant-derived C. (6) Changes in SOC, POC, and MAOC. (7) Soil C loss in the context of climate change. Processes (1)–(6) (current stage) were derived from the results of multi-site field trials, while process (7) (future stage) was based on the findings from mesocosm experiments. The aridity index data used in the figure were obtained from the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database-Version 3 (Global-AI_PET_v3)29. Solid arrows and dotted arrows signify differences in parameters under PM and DM, respectively, compared with NM. Upward-pointing red arrows indicate increases, whereas downward-pointing blue arrows denote decreases. NM conventional tillage without mulching, PM plastic film mulching, DM degradable film mulching, ABG aboveground biomass, BEG belowground biomass, Rs annual C emissions from soil respiration, Rh annual C emissions from heterotrophic respiration, Ra annual C emissions from autotrophic respiration, Hy-C hydrolytic C-acquiring enzymes, Ox-C oxidative C-acquiring enzymes, CUE microbial C use efficiency, SOC soil organic C, POC particulate organic C, MAOC mineral-associated organic C, dSOC SOC storage in farmland minus SOC storage in the previous year. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Some elements of this figure were created in BioRender. Xu, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z2vc7lf.

Methods

Experimental sites

Film mulching experiments were conducted at four locations on the Loess Plateau in China, representing the region’s predominant climate types. Film mulching significantly enhanced crop yields by nearly 50%, making it the primary agronomic practice for yield improvement in the area53. The sites were located in Yangling (34°20′N, 108°24′E), Changwu (35°14′N, 107°41′E), Pengyang (35°51′N, 106°48′E), and Anding (35°33′N, 104°35′E). The experiments were conducted on flat farmland cultivated for many years at all four sites. The field trials were conducted between 2015 and 2018 in Yangling, 2018 and 2020 in Changwu, 2013 and 2020 in Pengyang, and 2017 and 2019 in Anding (Supplementary Table 2). Supplementary Table 3 shows the four test sites’ climatic characteristics and surface soil properties.

Experimental design and crop management

The field experiment used a completely randomized block design, with three mulching practices tested at each of the four locations: (1) plastic film mulching (PM), with full coverage by polyethylene plastic film with a width of 120 cm; (2) degradable film mulching (DM), with full coverage by degradable film with a width of 120 cm; and (3) control (NM), with traditional flat planting and no mulching. The degradable film was white mulch made of polybutylene succinate (Showa Electric Co. Ltd, Japan). The degradation rate of degradable film mulch depends on temperature, humidity, soil fertility, and other factors, and it ultimately decomposes entirely into water and C dioxide. Each treatment was replicated thrice with nine plots per site, spaced 1–2 m apart.

The crop was spring maize planted at a density of 67,000 plants ha–1 (60 × 25 cm). Seeds were sown annually during April–May and harvested in August–October. At the time of sowing, N 140 kg ha–1 and P2O5 150 kg ha–1 were applied as the base fertilizer, and N 145 kg ha–1 was applied about 70 days after sowing. All treatments received no irrigation throughout the growth stage. Specific tillage management practices are detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

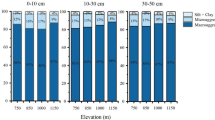

Soil sampling

Soil samples were collected each year when the crop was harvested. The samples were collected from the 0–10, 10–30, 30–60, and 60–100 cm soil depths at nine randomly selected points in each plot using a soil corer with a diameter of 5 cm. The soil samples from three points were thoroughly mixed to form a composite sample, resulting in three composite samples per plot. For each composite sample, roots and other debris were removed, and the sample was sieved through a 2 mm mesh. The composite samples were air-dried to determine the soil organic C (SOC) content. Additional fresh soil samples were collected from the four sites during the final year of the trial to analyze amino sugars, lignin phenols, microbial C use efficiency (CUE), phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs), extracellular enzyme activities (EEAs), and the abundances of functional genes.

SOC storage

The SOC contents were determined utilizing the K2Cr2O7 external heating method54. SOC storage in different soil depths was calculated using the equivalent soil mass method rather than the fixed depth method based on the observation that film mulching typically reduces the soil bulk density, which would lead to underestimation of the soil C storage under mulching conditions when using the fixed depth method55.

Assays of lignin phenols and amino sugars

Lignin phenols were quantified using the alkaline CuO oxidative hydrolysis method, where CuO-catalyzed oxidation of lignin macromolecules breaks the intermolecular ether bonds to release lignin phenol monomers56. Soil amino sugars were quantified to evaluate the microbial necromass according to the method described by Zhang and Amelung57.

Lignin phenols and amino sugar derivatives were analyzed using a TRACE 1300 gas chromatograph (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a VT-1 capillary chromatographic column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and flame ionization detector. The detailed methods used for determining lignin phenols are presented in the Supplementary Methods. The lignin phenols analyzed comprised syringyl (S; syringaldehyde, acetosyringone, and syringic acid), vanillyl (V; vanillin, acetylvanillone, and vanillic acid), and cinnamyl (C; p-coumaric and ferulic acids) phenols. The C/S and C/V ratios, as well as the acid–aldehyde ratios of V and S phenols ((Ad/Al)V and (Ad/Al)S), were used to assess the extent of lignin oxidation58,59. Assuming that CuO does not oxidize two-thirds of V phenols, and S and C phenols are liberated with 90% and 100% efficiency, respectively60, the content of plant-derived C in the soil (g kg−1) was estimated using the following formula:

where CV, CS, and CC (g kg−1) are the C contents of V-type, S-type, and C-type phenols, respectively, and 12% is the lignin content of maize plant residues61.

We analyzed four amino sugars comprising glucosamine (GlcN), galactosamine (GalN), mannose (ManN), and muramic acid (MurA). GlcN is commonly found in bacteria and fungi, but it mainly originates from the polysaccharide chitin in the cell walls of fungi in the soil. MurA is only found in the peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall and is an indicator of bacterial-derived C62,63. The sources of GalN and ManN remain disputed26,64. Assuming a molar ratio of 1:2 for GlcN relative to MurA in bacterial cells14,17, the estimated bacterial necromass C (BNC), fungal necromass C (FNC), and microbial-derived C were calculated using the GlcN and MurA concentrations as

where 179.17 and 251.23 are the relative molecular masses of GlcN and MurA, respectively, 9 is the conversion factor for GlcN to FNC64, and 45 is the conversion factor for MurA into BNC65.

Analysis of microbial traits

We utilized a fluorometric method to determine the activities of four hydrolases associated with C acquisition comprising α-1,4-glucosidase, β-1,4-glucosidase, cellobiose hydrolase, and β-1,4-xylosidase66 (Supplementary Table 4). The activities of non-hydrolytic enzymes (polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase) were determined using the pyrogallol colorimetric method67. Microbial communities were quantified based on PLFAs68 (Supplementary Table 5). The microbial CUE was determined using the 18O–H2O incubation method69. The detailed methods used for determining EEAs, PLFAs, and CUE are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

HT-qPCR (SmartChip Real-Time PCR System, WaferGen Biosystems, Fremont, USA) was employed to quantitatively assess the abundances of functional genes associated with C degradation and fixation70. Details of the functional genes and corresponding gene chip primers are provided in Supplementary Table 6. The melting curve was automatically generated using WaferGen software. Functional genes with multiple melting peaks or amplification efficiencies outside the range of 1.8–2.2 were excluded by SmartChip qPCR software. Further analysis was conducted only if the negative control exhibited no amplification and the threshold cycle (Ct) was <31. The absolute abundance of a functional gene (copies g–1) was calculated using the following formula:

where a is the relative copy number of the functional gene, b (copies μL–1) is the absolute abundance of the 16S rRNA gene, c is the relative copy number of the 16S rRNA gene, d (ng μL–1) is the DNA concentration, m (μg) is the extracted DNA mass, and n (g) is the mass of the extracted soil sample.

Incubation experiment

Soil samples in the topsoil (0–30 cm) and subsoil (30–100 cm) were collected from 17 farmland sites across China. These sites span over 3800 km from east to west (80°45′E–126°38′E), and over 1500 km from north to south (34°20′N–47°26′N), covering the major Chinese dryland regions (Supplementary Fig. 23). The significant variability in soil properties across the sampling sites allowed us to effectively evaluate the impacts of different mulching practices on soil C pools under climate change. A total of 153 soil samples (17 sites × 3 treatments × 3 replicates) were collected for the incubation experiment. At each site, nine sampling points were randomly selected within a 50 × 50 m area, and intact topsoil (0–30 cm) and subsoil (30–100 cm) samples were collected. The samples were placed into custom-made polyvinyl chloride cylinders (30 cm inner diameter, 110 cm height) in the order of the soil depths and transported to the laboratory. The soil columns collected at each site were consistent with the field experiment setup, with treatments divided into PM, DM, and NM. Incubation was conducted in an artificial intelligence climate chamber designed to simulate climate change. The CO2 concentration was adjusted to represent the projected atmospheric levels for the year 2100, based on the intermediate Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP5-8.5). The temperature was maintained at 15 °C, and the humidity was controlled at 55%. A 45-day preincubation was conducted to ensure soil samples reached a stable state, followed by SOC, and microbial- and plant-derived C measurements. The samples were then incubated for an additional 367 days, after which SOC, microbial- and plant-derived C contents were re-measured in both the topsoil and subsoil. The SOC loss during the incubation period was calculated using different mulching practices and the contributions of microbial- and plant-derived C.

Statistical analysis

Levene’s test was first used to verify the homogeneity of variance before conducting a one-way analysis of variance to assess the effects of film mulching on SOC and its components (microbial- and plant-derived C). We also evaluated the impacts on biological (ABG, BEG, EEAs, PLFAs, CUE, and functional genes associated with C degradation and fixation) and abiotic factors (ST, SWC, CERs, CERh, and CERa). The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Random forest model analysis was conducted using the “randomForest” package in R to identify key variables that affected microbial- and plant-derived C71,72. The “rfPermute” package in R was used to assess the significance of variables through permutation tests73. To improve the accuracy of the predictions, 10-fold cross-validation was conducted with three replicates to optimize the model parameters. The “trainControl” function from the “caret” package was applied to set the cross-validation parameters and grid search to identify the optimal combination. Following parameter optimization, the random forest model was reconstructed, and the importance and significance of each variable were re-evaluated. Further regression analysis was conducted to investigate the relationships between different C sources and the most influential factors identified through random forest screening. Linear mixed-effects (LME) modeling was employed to analyze the relationships between the abundances of functional genes (C-degradation genes, C-fixation genes, and their sum) and dSOC. The model allowed nested covariance structures, particularly site-level relationships nested within overall relationships to effectively address the measurement errors across various sites. The study site was included as a random effect, and functional gene abundance was treated as a fixed effect. The results indicated that only the linear mixed-effects model between the abundance of C-degradation genes and dSOC was statistically significant (Supplementary Table 1). The “lmer” function in R was utilized to construct a model to evaluate the effects of various functional genes on the response of dSOC. The model was specified as: dSOC ~ amyA + apu + iso-plu + sga + abfA + manB + xylA + cdh + cex + naglu + chiA + pgu + glx + lig + mnp + pox + (1|Site). The control parameters were adjusted to ignore singularity convergence, and the restricted maximum-likelihood estimation method was used for parameter estimation. The dredge function in the “MuMIn” package in R was employed to perform stepwise selection and to identify the optimal model based on Akaike’s information criterion (Supplementary Table 7). Finally, we utilized the “plspm” package in R (version 4.1.3) to perform PLS-PM analysis in order to determine factors that influenced the soil C pool74.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sanderman, J., Hengl, T. & Fiske, G. J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9575–9580 (2017).

Lehmann, J. & Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 528, 60–68 (2015).

Plaza, C. et al. Soil resources and element stocks in drylands to face global issues. Sci Rep.-Uk 8, 13788 (2018).

Kasirajan, S. & Ngouajio, M. Polyethylene and biodegradable mulches for agricultural applications: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 32, 501–529 (2012).

Steinmetz, Z. et al. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. Total Environ. 550, 690–705 (2016).

Cao, J. et al. Agricultural soil plastic as a hidden carbon source stimulates microbial activity and increases carbon dioxide emissions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 198, 107151 (2023).

Huang, Y., Liu, Q., Jia, W., Yan, C. & Wang, J. Agricultural plastic mulching as a source of microplastics in the terrestrial environment. Environ. Pollut. 260, 114096 (2020).

Huang, F., Zhang, Q., Wang, L., Zhang, C. & Zhang, Y. Are biodegradable mulch films a sustainable solution to microplastic mulch film pollution? A biogeochemical perspective. J. Hazard. Mater. 459, 132024 (2023).

Qadeer, A., Ajmal, Z., Usman, M., Zhao, X. & Chang, S. Agricultural plastic mulching as a potential key source of microplastic pollution in the terrestrial ecosystem and consequences. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 175, 105855 (2021).

Hofmann, T. et al. Plastics can be used more sustainably in agriculture. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 332 (2023).

Lavallee, J. M., Soong, J. L. & Cotrufo, M. F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Global Change Biol. 26, 261–273 (2020).

Lehmann, J. et al. Persistence of soil organic carbon caused by functional complexity. Nat. Geosci. 13, 529–534 (2020).

Angst, G. et al. Unlocking complex soil systems as carbon sinks: multi-pool management as the key. Nat. Commun. 14, 2967 (2023).

Cotrufo, M. F. & Lavallee, J. M. Soil organic matter formation, persistence, and functioning: a synthesis of current understanding to inform its conservation and regeneration. Adv. Agron. 172, 1–66 (2022).

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P. & Jastrow, J. D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nature Microbiology 2, 17105 (2017).

Rocci, K. S. et al. Bridging 20 years of soil organic matter frameworks: empirical support, model representation, and next steps. J. Geophys. Res.—Biogeosci. 129, e2023JG007964 (2024).

Joergensen, R. G. Amino sugars as specific indices for fungal and bacterial residues in soil. Biol. Fert. Soils 54, 559–568 (2018).

Ma, T. et al. Divergent accumulation of microbial necromass and plant lignin components in grassland soils. Nat. Commun. 9, 3480 (2018).

Sokol, N. W., Sanderman, J. & Bradford, M. A. Pathways of mineral-associated soil organic matter formation: integrating the role of plant carbon source, chemistry, and point of entry. Global Change Biol. 25, 12–24 (2019).

Liang, C., Amelung, W., Lehmann, J. & Kastner, M. Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Global Change Biol. 25, 3578–3590 (2019).

Hu, H. et al. Reducing the uncertainty in estimating soil microbial-derived carbon storage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2401916121 (2024).

Mo, F. et al. How plastic mulching affects net primary productivity, soil C fluxes and organic carbon balance in dry agroecosystems in China. J. Clean. Prod. 263, 121470 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Is crop biomass and soil carbon storage sustainable with long-term application of full plastic film mulching under future climate change? Agric. Syst. 150, 67–77 (2017).

Wang, Y. P. et al. Multi-site assessment of the effects of plastic-film mulch on the soil organic carbon balance in semiarid areas of China. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 228, 42–51 (2016).

Yu, Y. X., Zhang, Y. X., Xiao, M., Zhao, C. Y. & Yao, H. Y. A meta-analysis of film mulching cultivation effects on soil organic carbon and soil greenhouse gas fluxes. Catena 206, 105483 (2021).

Zosso, C. U., Ofiti, N. O. E., Torn, M. S., Wiesenberg, G. L. B. & Schmidt, M. W. I. Rapid loss of complex polymers and pyrogenic carbon in subsoils under whole-soil warming. Nat. Geosci. 16, 344–348 (2023).

Pries, C. E. H. et al. The deep soil organic carbon response to global change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 54, 375–401 (2023).

Glaser, B., Turrion, M. B. & Alef, K. Amino sugars and muramic acid - biomarkers for soil microbial community structure analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 399–407 (2004).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the global aridity index and potential evapotranspiration database. Sci. Data 9, 409 (2022).

Melillo, J. M. et al. Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world. Science 358, 101–104 (2017).

Wang, C. & Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial-fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 18, wrae073 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Microbial mediation of carbon-cycle feedbacks to climate warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 106–110 (2012).

Liu, Z. H. et al. Soil respiration in response to biotic and abiotic factors under different mulching measures on rain-fed farmland. Soil Tillage Res. 232, 105749 (2023).

Qu, J. et al. Smooth vetch (Vicia villosa var.) coupled with ball-milled composite mineral derived from shell powder and phosphate rock for remediation of cadmium-polluted farmland: insights into synergetic mechanisms. ACS ES&T Eng. 4, 2054–2067 (2024).

Feng, W. T. et al. Enhanced decomposition of stable soil organic carbon and microbial catabolic potentials by long-term field warming. Global Change Biol. 23, 4765–4776 (2017).

Shao, P. S., Lynch, L., Xie, H. T., Bao, X. L. & Liang, C. Tradeoffs among microbial life history strategies influence the fate of microbial residues in subtropical forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 153, 108112 (2021).

Liu, Z. H. et al. Plastic film mulching and biochar amendment enhance maize yield and nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency by reducing gaseous nitrogen losses. Field Crop Res. 289, 108714 (2022).

Craine, J. M., Morrow, C. & Fierer, N. Microbial nitrogen limitation increases decomposition. Ecology 88, 2105–2113 (2007).

Meyer, N., Welp, G., Bornemann, L. & Amelung, W. Microbial nitrogen mining affects spatio-temporal patterns of substrate-induced respiration during seven years of bare fallow. Soil Biol. Biochem. 104, 175–184 (2017).

Kallenbach, C. M., Frey, S. D. & Grandy, A. S. Direct evidence for microbial-derived soil organic matter formation and its ecophysiological controls. Nat. Commun. 7, 13630 (2016).

Banfield, C. C., Dippold, M. A., Pausch, J., Hoang, D. T. T. & Kuzyakov, Y. Biopore history determines the microbial community composition in subsoil hotspots. Biol. Fertil. Soils 53, 573–588 (2017).

Moritz, L. K., Liang, C., Wagai, R., Kitayama, K. & Balser, T. C. Vertical distribution and pools of microbial residues in tropical forest soils formed from distinct parent materials. Biogeochemistry 92, 83–94 (2009).

Roth, P. J. et al. Accumulation of nitrogen and microbial residues during 2000 years of rice paddy and non-paddy soil development in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Global Change Biol. 17, 3405–3417 (2011).

Sradnick, A., Oltmanns, M., Raupp, J. & Joergensen, R. G. Microbial residue indices down the soil profile after long-term addition of farmyard manure and mineral fertilizer to a sandy soil. Geoderma 226, 79–84 (2014).

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006).

Jagermeyr, J. et al. Climate impacts on global agriculture emerge earlier in new generation of climate and crop models. Nat. Food 2, 875 (2021).

Ding, F. et al. Increased soil organic matter after 28 years of nitrogen fertilization only with plastic film mulching is controlled by maize root biomass. Sci. Total Environ. 810, 152244 (2022).

Cotrufo, M. F., Haddix, M. L., Kroeger, M. E. & Stewart, C. E. The role of plant input physical-chemical properties, and microbial and soil chemical diversity on the formation of particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 168, 108648 (2022).

Fontaine, S. et al. Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply. Nature 450, 277–U210 (2007).

Soong, J. L. et al. Five years of whole-soil warming led to loss of subsoil carbon stocks and increased CO2 efflux. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd1343 (2021).

Xiao, K.-Q. et al. Introducing the soil mineral carbon pump. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 135–136 (2023).

Weverka, J., Runte, G. C., Porzig, E. L. & Carey, C. J. Exploring plant and soil microbial communities as indicators of soil organic carbon in a California rangeland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 178, 108952 (2023).

Sun, D. B. et al. An overview of the use of plastic-film mulching in China to increase crop yield and water-use efficiency. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 1523–1526 (2020).

Ellert, B. H., Janzen, H. H., VandenBygaart, A. J. & Bremer, E. Measuring change in soil organic carbon storage. In Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis (eds. Carter, M. R., Gregorich, E. G) 25–38 (CRC press, 2007).

von Haden, A. C., Yang, W. H. & DeLucia, E. H. Soils’ dirty little secret: depth-based comparisons can be inadequate for quantifying changes in soil organic carbon and other mineral soil properties. Global Change Biol. 26, 3759–3770 (2020).

Otto, A. & Simpson, M. J. Analysis of soil organic matter biomarkers by sequential chemical degradation and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 30, 272–282 (2007).

Zhang, X. D. & Amelung, W. Gas chromatographic determination of muramic acid, glucosamine, mannosamine, and galactosamine in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28, 1201–1206 (1996).

Chen, X. B. et al. Contrasting pathways of carbon sequestration in paddy and upland soils. Global Change Biol. 27, 2478–2490 (2021).

Kogel, I. Estimation and decomposition pattern of the lignin component in forest humus layers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 18, 589–594 (1986).

Hautala, K., Peuravuori, J. & Pihlaja, K. Estimation of origin of lignin in humic DOM by CuO-oxidation. Chemosphere 35, 809–817 (1997).

Burgess, M. S., Mehuys, G. R. & Madramootoo, C. A. Decomposition of grain-corn residues (Zea mays L.): a litterbag study under three tillage systems. Can. J. Soil Sci. 82, 127–138 (2002).

Amelung, W., Miltner, A., Zhang, X. & Zech, W. Fate of microbial residues during litter decomposition as affected by minerals. Soil Sci. 166, 598–606 (2001).

Guggenberger, G., Frey, S. D., Six, J., Paustian, K. & Elliott, E. T. Bacterial and fungal cell-wall residues in conventional and no-tillage agroecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 63, 1188–1198 (1999).

Engelking, B., Flessa, H. & Joergensen, R. G. Shifts in amino sugar and ergosterol contents after addition of sucrose and cellulose to soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 2111–2118 (2007).

Appuhn, A. & Joergensen, R. G. Microbial colonisation of roots as a function of plant species. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 1040–1051 (2006).

Marx, M. C., Wood, M. & Jarvis, S. C. A microplate fluorimetric assay for the study of enzyme diversity in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33, 1633–1640 (2001).

Chance, B. & Maehly, A. C. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 136, 764–775 (1955).

Olsson, P. A. Signature fatty acids provide tools for determination of the distribution and interactions of mycorrhizal fungi in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 29, 303–310 (1999).

Spohn, M., Klaus, K., Wanek, W. & Richter, A. Microbial carbon use efficiency and biomass turnover times depending on soil depth—implications for carbon cycling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 96, 74–81 (2016).

Zheng, B., Zhu, Y., Sardans, J., Penuelas, J. & Su, J. QMEC: a tool for high-throughput quantitative assessment of microbial functional potential in C, N, P, and S biogeochemical cycling. Sci. China-Life Sci. 61, 1451–1462 (2018).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Hengl, T., Nussbaum, M., Wright, M. N., Heuvelink, G. B. M. & Graeler, B. Random forest as a generic framework for predictive modeling of spatial and spatio-temporal variables. Peerj 6, e5518 (2018).

Archer, E. rfPermute: Estimate Permutation p-Values for Random Forest Importance Metrics. R package version 1.5.2 https://github.com/EricArcher/rfPermute (2013).

Sanchez, G., Trinchera, L. & Russolillo, G. plspm: Tools for Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) R package version 0.4, 9 https://github.com/gastonstat/plspm (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42425705, U23A2052, and 42407421), China 111 Project (No. B12007), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFE0101302). We thank the landowners for granting site access and all those who supported our soil sampling. We also acknowledge BaiHui Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Chengdu, China, for determining the PLFA and CUE of the soil samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. and Z.J. designed the study. Z.L. collected the data and performed the analysis, and led the writing of the manuscript. Z.L., C.Z., N.Z., J.W., Z.Y.L., Y.U., and N.F. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. T.W.C., Y.H., Y.Y.H., Y.X., S.Z., Y.K., K.H.M.S., Z.C., S.X.C., M.X., C.M., Z.J., and Y.C. contributed to discussing the results and writing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bin Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Zhao, C., Zhang, N. et al. Degradable film mulching increases soil carbon sequestration in major Chinese dryland agroecosystems. Nat Commun 16, 5029 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60036-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60036-5