Abstract

Electrocatalytic methods that facilitate the asymmetric reductive coupling of two π-components with complete control over regio-, stereo-, and enantioselectivity remain underexplored. Herein, we report a highly regio- and enantioselective cobaltaelectro-catalyzed alkyne-aldehyde coupling reaction, in which protons and electrons serve as the hydrogen source and reductant, respectively. Earth-abundant cobalt and air-stable (S,S)−2,3-bis(tert-butylmethylphosphino)quinoxaline (QuinoxP*) are used as the catalyst and ligand, respectively. A series of enantioenriched allylic alcohols can be constructed with excellent regio- (>19:1), stereo- (>19:1 E:Z), and enantioselectivity (up to 98% ee).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

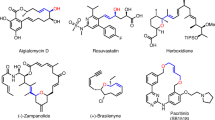

Allylic alcohols are integral subunits of numerous biologically significant natural products, as well as versatile building blocks for a range of synthetic applications1,2, including π-allyl chemistry3, SN2’ displacements4, cationic cyclizations5, Claisen rearrangements6, and related sigmatropic processes6. Traditionally, the enantioselective preparation of allylic alcohols involves the generation of alkenylmetal intermediates from alkynes in the presence of stoichiometric amounts of R2Zn or RMgX and further reaction with aldehydes via asymmetric addition7,8,9. These methods are limited by synthetic inefficiencies, chemical waste issues, and low sustainability. Asymmetric reductive coupling of alkynes and aldehydes has thus emerged as a straightforward strategy for obtaining these important substructures, and substantial progress has been made in recent decades (Fig. 1a). However, these transformations require excess reducing agent, e.g., explosive H210,11, pyrophoric Et3B/Me2Zn12,13,14,15,16,17, mass-intensive silane18,19,20,21, or Hantzsch ester (HE)22,23,24, which may lead to serious safety issues, high costs, low functional group tolerance, and low atom economy. Therefore, it is desirable to develop new strategy for highly regio- and enantioselective alkyne-aldehyde coupling using an inexpensive, safe, and easily manipulated reductant.

Electrosynthesis offers an approach for sustainably mitigating the aforementioned challenges because it uses electrons as inherently safe redox reagents, thereby avoiding the need for stoichiometric and reactive (sometimes dangerous) oxidants/reductants25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. To date, there are few examples of electroreductive coupling of two π-components34,35,36,37,38,39. Mechanistic insights from the successful reports indicate that active radical species are generated in situ via direct cathodic reduction of π-components and serve as the key intermediates. These inherently energetic and reactive radical species make it difficult to ensure enantioselective control. Despite progress in asymmetric electrosynthesis25,27,28,29,31, electrocatalytic methods that enable asymmetric reductive coupling of two π-components with full regio-, stereo-, and enantioselectivity control are, to our knowledge, absent from the literature.

Herein, we propose an electroreductive alkyne-aldehyde coupling reaction using protons, electrons, earth-abundant cobalt, and QuinoxP* (L1) as the hydrogen source, reductant, catalyst, and ligand, respectively (Fig. 1b). This strategy allows for complete control over the product selectivity. Various enantioenriched allylic alcohols are constructed using.

Results and discussion

This approach, demonstrating its excellent regio- (>19:1), stereo- (>19:1 E:Z), and enantioselectivity (up to 98% ee).

The proposed electroreductive strategy is triggered by the low-valent metal-mediated oxidative cyclometallation of alkynes and aldehydes. Further quenching of the afforded five-membered metallacycle with protons and electrons leads to the desired allylic alcohols and recycles the catalyst. However, low-valent transition metals are often highly reactive because they are easily oxidized to high-valent metal-hydride species following protonation; this reactivity is well established in electrochemistry40,41,42,43,44. Once metal-hydride is formed along with the desired oxidative cyclometallation pathway, the regio-, stereo- and enantioselectivity control will turn to be multiple, making the outcome hard to control or predict. Another challenge is that the competing hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is thermodynamically favorable45, and therefore, it competes with the crucial protonation process. Accordingly, it is necessary to select a suitable proton source (i.e., sufficiently inert toward metal-hydride formation and kinetically suppresses H2 formation) to ensure successful enantioselective electroreductive alkyne-aldehyde coupling.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was used to explore the interactions between [Co(OAc)2/L1] with different proton sources. In the CV profile of [Co(OAc)2/L1], the redox peak at –0.96 V were assigned to the CoII/CoI couples (Fig. 2a, for details, please see Figs. S3–5 in the SI). The addition of Acetic Acid (pKa = 4.74) to the solution significantly increased the current for both the CoII/CoI peak. A negligible change in the peak currents was observed when the less acidic 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE; pKa = 12.5) was added. These results implied that stronger acids (e.g., Acetic Acid) facilitated protonation of the low-valent cobalt complex, whereas less acidic 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol led to relatively inefficient protonation.

a CV studies of the interaction of [Co(OAc)2/L1] with different proton sources. b Comparison of hydrogen current for [Co(OAc)2/L1] with different proton sources under a constant cathode potential at −1.6 V vs Ag/AgCl. c Effects of proton sources on electroreductive alkyne-aldehyde coupling; For details, see the Supplementary information.

Furthermore, differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (DEMS) showed that a higher hydrogen evolution reaction current was observed for [Co(OAc)2/L1] with Acetic Acid (Fig. 2b), whereas there was negligibly small hydrogen evolution reaction current with 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol. These results revealed that a relatively weak acidic proton source could efficiently inhibit the undesired metal-hydride formation and hydrogen evolution reaction, thereby promoting the reaction efficient and selectivity.

Next, the effects of proton source on the electroreductive coupling of alkyne (1a) and aldehyde (1b) was investigated in an undivided cell equipped with a magnesium anode and a graphite felt cathode using [Co(OAc)2/L1]. As shown in Fig. 2c, indeed, the pKa value of proton source was crucial for determining the reaction efficiency and selectivity. More acidic acetic acid led to low yields and selectivities, while weakly acidic 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol afforded high yields and excellent regio-, stereo-, and enantioselectivity.

Investigation of the reaction conditions

Having established the proof of concept, the enantioselective electroreductive coupling of alkynes and aldehydes was optimized. As shown in Table 1, the desired allylic alcohol 1 was isolated in 77% yield with excellent regio- (>19:1), stereo- (>19:1), and enantioselectivity (95% ee) when using CoBr2 as the catalyst, QuinoxP* (L1) as the ligand, and TFE as the proton source (entry 1). When other Co precursor, such as Co(OAc)2, and Co(acac)2, were applied instead of CoBr2, the yield of the desired product decreased more or less (entries 2 and 3). A nonsacrificial anode or a platinum cathode which favored hydrogen evolution reaction, was not suitable for this reactivity (entries 4-5). Notably, the solvent influenced the reaction efficiency significantly (entries 6-7), and dimethylacetamide (DMAc) was the optimal solvent. When other chiral diphosphine ligands (L2–L3), bisoxazoline ligands (L4), or phosphinooxazoline ligands (L5) were used instead of L1, lower enantioselectivities and yields were obtained (entries 8-11). Notably, as an environmentally friendly source of protons, H2O can be used as hydrogen source as well, and the desired allylic alcohol 1 was isolated in 45% yield with excellent regioselectivity (>19:1), stereoselectivity (>19:1), and enantioselectivity (88% ee, entry 12). Additional experiments confirmed that proton source, and electricity were all critical components of the reaction (entries 13-14).

Scope of substrates

Applying the optimized conditions, we investigated the generalizability of this protocol with respect to alkynes. As shown in Fig. 3, a variety of unsymmetrical aryl-substituted internal alkynes, either substituted with electron-rich (e.g., OMe, SMe, alkyl) or electron-deficient groups (Ph, Cl, ester, CF3, ketone), were viable in this reaction, giving the desired chiral allylic alcohols (1–15) with excellent regio- (>19:1) and enantioselectivities (93%-95% ee). The electronic properties of the substrates had a slight impact on the reaction efficiency. Alkynes substituted with naphthalene and carbazole reacted smoothly with 1b, affording the corresponding products 16 and 17 in moderate yields with 94%-98% ee. Heteroaryl alkynes, such as 5-(prop-1-yn-1-yl)benzofuran and 2-(prop-1-yn-1-yl)thiophene, which are often sensitive to oxidative conditions, were tolerated in this reaction, furnishing 18 and 19, respectively, with excellent regio- (>19:1), stereo- (>19:1 E:Z), and enantioselectivities (93%-95% ee). Notably, nonmethyl substituted alkynes (e.g., ethyl, cyclopropyl, 3-chloropropyl, and n-propyl) were amenable to this protocol with excellent selectivity, which often lead to in low regioselectivity in previously reported method using ZnMe2 as reductant17. They afforded structurally diverse enantioenriched allylic alcohols (20–23, respectively) with excellent selectivities (>19:1 rr, >19:1 E:Z, 94%-96% ee), albeit in lower yields. Internal dialkyl alkynes (e.g., 24) were not conducive, leading to low regio- and enantioselectivities.

Next, we explored the scope of the reaction between prop-1-yn-1-ylbenzene (1a) and a variety of aldehydes. As shown in Fig. 4, a series of aldehydes bearing electron-rich (e.g., OMe, Me) or electron-poor groups (e.g., F, Cl, CO2Me, OCF3) reacted smoothly with 1a, furnishing the corresponding chiral allylic alcohols (25–33) in good to excellent yields with high enantioselectivity. The naphthyl-substituted aldehyde (34), which easily undergoes electrochemical Birch reduction via electron transfer-proton transfer (ET-PT)46, was well tolerated in this reaction. In addition, 4-(2-pyridinyl)benzaldehyde (35) was compatible with this protocol, despite exhibiting relatively low reactivity, and no evidence of pyridine-directed C–H activation was observed. Alkyl aldehyde was tested as a case study of isobutyraldehyde, and the desired product (36) was obtained in moderate yield with 76% ee.

The developed electrochemical alkyne-aldehyde coupling reaction was also implemented in late-stage modifications of various natural products and pharmaceutical derivatives. A series of alkynes derived from chrysanthemum acid, flurbiprofen, clofibric acid, oleic acid, and ibuprofen reacted efficiently with 1b and afforded the desired products (37–41) with excellent selectivities. Furthermore, in a scale-up experiment with 1, the yield decreased slightly, but the excellent selectivities (>19:1 rr, >19:1 E:Z, 93% ee) were maintained.

Mechanistic studies

To gain mechanistic insights, the working voltage of the model reaction was monitored over the course of the electrolysis. The cathodic potential decreased gradually over the first 90 min and thereafter remained at approximately −1.5 V (Fig. 5a). Notably, the cathodic potential was significantly more negative than the reduction potential required for CoII/CoI reduction (Fig. 2b), but more positive than the reduction potential needed for the reductions of 1a and 2b (Fig. 5b). A plot of the yield of 28 over time for the model reaction revealed an inductive period for this reaction (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, a competitive racemic background process was not detected because the ee values of the product remained constant (92%-94% ee) when varying the current intensity from 1 to 10 mA (Fig. 5d). This result confirmed that the reaction efficiency and enantioselectivity originated from cobaltaelectro-catalyzed alkyne-aldehyde coupling. Thus, electroreductive generation of a reactive low-valent catalyst species is needed for this protocol. In addition, a linear relationship was observed between the enantiopurities of L1 and product 1 (Fig. 5e), revealing that a monomeric Co-complex bearing a single chiral phosphine ligand is involved in the enantioselectivity-determining step47. This cobalt complex I was characterized by X-ray diffraction (Fig. 5f).

To explore the reaction mechanism, we conducted control experiments. Firstly, the desired product was isolated in 78% yield with 92% ee when cobalt complex I was employed as the catalyst (Fig. 6a), indicating that this Co-complex I is the catalytic species in this protocol. Radical scavengers 2,4-di-tert-butyl-4- methylphenol (BHT) and 1,1-diphenylethylene marginally affected the reaction efficiency (Fig. 6b), suggesting that radical intermediates were not involved. Furthermore, the desired chiral allylic alcohol 1 was not detected when propa-1,2-dien-1- ylbenzene (3a) was employed instead of alkyne 1a, thus ruling out that allene was generated in situ and served as the key intermediate (Fig. 6c). Approximately 69% deuterium was incorporated into the vinyl position of product 1 when D2O was used as the proton source, thereby verifying that protons were the hydrogen source for this reaction (Fig. 6d).

On the basis of the experimental results presented herein and in previous studies18,19,20,23, a potential mechanism is proposed (Fig. 7). Initially, the low-valent (L*)Con species A is formed via cathodic reduction48,49. Then, coordination of the alkyne and aldehyde with A, followed by oxidative cyclization, furnishes the metallacycle intermediate C. Further protonation of C by 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol leads to the formation of chiral allylic alcohols and (L*)Co(n+2) species D50. Finally, A is regenerated via cathodic reduction of D. As the cathodic potential (−1.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl, Fig. 5a) during electrolysis was significantly more negative than the reduction potential required for CoII/CoI reductions (–0.96 V vs. Ag/AgCl, Fig. 2b), thus (L*)CoI might be existed in this protocol.

In summary, this report describes a highly enantioselective electroreductive coupling of alkynes and aldehydes. The protocol uses commercially available cobalt and QuinoxP*, where protons and electrons serve as the hydrogen source and reductant, respectively. A broad range of chiral allylic alcohols can be efficiently synthesized with excellent regio- (>19:1), stereo- (>19:1 E:Z), and enantioselectivities (up to 98% ee). Mechanistic studies suggest that a monomeric Co complex bearing a single chiral phosphine ligand is involved in the enantioselectivity-determining step. Further developments of enantioselective cross-couplings of other π-containing compounds are ongoing in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure

An oven-dried 10 mL two-necked glass cell with a teflon-coated magnetic stir bar (Ф 7 mm * L 13.5 mm) was cooled to ambient temperature. nBu4NBF4 (0.05 M, 98.8 mg), aldehydes (3.0 equiv., 0.6 mmol) were successively added into the 10 mL two-necked glass cell. The Mg anode (15 mm × 15 mm × 0.5 mm) and graphite felt (15 mm × 15 mm × 3.0 mm), embedded a rubber cap with a distance of around 0.5 cm between them, were inserted into the 10 mL two-necked glass cell. Then, the two-necked glass cell was transferred into the glovebox for pumping three times. CoBr2 (10 mol%, 4.4 mg), (S,S)-QuinoxP*(L1) (10 mol%, 6.7 mg) were added in a glovebox. The reaction cell was sealed and moved out from the glovebox. The dry DMAc (6.0 mL), alkynes (1.0 equiv., 0.2 mmol), and TFE (2.0 equiv., 29 μL) were successively added into the mixture under argon. Then the resulting mixture was stirred (r.p.m. = 1000) at room temperature (25 °C), and electrolyzed under a constant current of 3.0 mA from DC power for 4 h 28 min under argon immediately. After reaction, sat. NH4Cl aq. was poured into the reaction mixture and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was washed with water, dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The corresponding products were then purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (column type: Biotage Rensing Cartridge 10 g; eluent: petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 19:1 → 9:1).

Data availability

Data relating to the characterization data of materials and products, general methods, optimization studies, experimental procedures, mechanistic studies and NMR spectra are available in the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2374768 (5) and 2366356 (cobalt complex I). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All data are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Gil, A., Albericio, F. & Álvarez, M. Role of the Nozaki–Hiyama–Takai–Kishi reaction in the synthesis of natural products. Chem. Rev. 117, 8420–8446 (2017).

Butt, N. A. & Zhang, W. Transition metal-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions with unactivated allylic substrates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7929–7967 (2015).

Godleski, S. A. in Comprehensive Organic Synthesis (eds Trost, Barry M. & Fleming, Ian) 585–661 (Pergamon, 1991).

Lipshutz, B. H. & Sengupta, S. in Organic Reactions John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 135–631.

Overman, L. E. Charge as a key component in reaction design. the invention of cationic cyclization reactions of importance in synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 25, 352–359 (1992).

Wipf, P. in Comprehensive Organic Synthesis (eds Trost, Barry M. & Fleming, Ian) 827–873 (Pergamon, 1991).

Oppolzer, W. & Radinov, R. N. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of Secondary (E)-allyl alcohols from acetylenes and aldehydes via (1-alkenyl)zinc intermediates. preliminary communication. Helv. Chim. Acta 75, 170–173 (Wiley-VHCA AG, Zurich, Switzerland, 1992).

Takayanagi, Y., Yamashita, K., Yoshida, Y. & Sato, F. Synthesis of chiral allylic alcohols by the reaction of chiral titanium–alkyne complexes with carbonyl compounds. Chem. Commun. 15, 1725–1726 (1996).

Wipf, P. & Ribe, S. Zirconocene−zinc transmetalation and in situ catalytic asymmetric addition to aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 63, 6454–6455 (1998).

Komanduri, V. & Krische, M. J. Enantioselective reductive coupling of 1,3-enynes to heterocyclic aromatic aldehydes and ketones via rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation: mechanistic insight into the role of brønsted acid additives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16448–16449 (2006).

Huddleston, R. R., Jang, H.-Y. & Krische, M. J. First catalytic reductive coupling of 1,3-diynes to carbonyl partners: a new regio- and enantioselective C−C bond forming hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11488–11489 (2003).

Luanphaisarnnont, T., Ndubaku, C. O. & Jamison, T. F. anti−1,2-Diols via Ni-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkynes and α-oxyaldehydes. Org. Lett. 7, 2937–2940 (2005).

Miller, K. M., Colby, E. A., Woodin, K. S. & Jamison, T. F. Asymmetric catalytic reductive coupling of 1,3-enynes and aromatic aldehydes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 347, 1533–1536 (2005).

Miller, K. M., Huang, W.-S. & Jamison, T. F. Catalytic asymmetric reductive coupling of alkynes and aldehydes: enantioselective synthesis of allylic alcohols and α-hydroxy ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 3442–3443 (2003).

Colby, E. A. & Jamison, T. F. P-chiral, monodentate ferrocenyl phosphines, novel ligands for asymmetric catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 68, 156–166 (2003).

Nie, M., Fu, W., Cao, Z. & Tang, W. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed alkylative alkyne–aldehyde cross-couplings. Org. Chem. Front. 2, 1322–1325 (2015).

Yang, Y., Zhu, S.-F., Zhou, C.-Y. & Zhou, Q.-L. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective alkylative coupling of alkynes and aldehydes: synthesis of chiral allylic alcohols with tetrasubstituted olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14052–14053 (2008).

Check, C. T. et al. Ferrocene-based planar chiral imidazopyridinium salts for catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 4264–4268 (2015).

Chaulagain, M. R., Sormunen, G. J. & Montgomery, J. New N-heterocyclic carbene ligand and its application in asymmetric nickel-catalyzed aldehyde/alkyne reductive couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9568–9956 (2007).

Wang, H. et al. NHC ligands tailored for simultaneous regio- and enantiocontrol in nickel-catalyzed reductive couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9317–9324 (2017).

Liu, J. M. et al. Chemodivergent, enantio- and regioselective couplings of alkynes, aldehydes and silanes enabled by nickel/N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Sci. Bull. 70, 674–682 (2024).

Wang, Y., Mi, R., Yu, S. & Li, X. Expedient synthesis of axially and centrally chiral diaryl ethers via cobalt-catalyzed photoreductive desymmetrization. ACS Catal. 14, 4638–4647 (2024).

Li, Y.-L., Zhang, S.-Q., Chen, J. & Xia, J.-B. Highly regio- and enantioselective reductive coupling of alkynes and aldehydes via photoredox cobalt dual catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7306–7313 (2021).

Jiang, H. et al. Photoinduced cobalt-catalyzed desymmetrization of dialdehydes to access axial chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6944–6952 (2023).

Wang, X., Xu, X., Wang, Z., Fang, P. & Mei, T.-S. Advances in asymmetric organotransition metal-catalyzed electrochemistry. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 40, 3738–374 (2020).

Yamamoto, K., Kuriyama, M. & Onomura, O. Anodic oxidation for the stereoselective synthesis of heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 105–120 (2020).

Jiao, K.-J. et al. The applications of electrochemical synthesis in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Catal. 2, 3019–3047 (2022).

Lin, Q., Li, L. & Luo, S. Asymmetric electrochemical catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 10033–10044 (2019).

Chang, X., Zhang, Q. & Guo, C. Asymmetric electrochemical transformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12612–1262 (2020).

Yamamoto, K., Kuriyama, M. & Onomura, O. Asymmetric electrosynthesis: recent advances in catalytic transformations. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 28, 100714 (2021).

Ghosh, M., Shinde, V. S. & Rueping, M. A review of asymmetric synthetic organic electrochemistry and electrocatalysis: concepts, applications, recent developments and future directions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 15, 2710–274 (2019).

Moeller, K. D. Using physical organic chemistry to shape the course of electrochemical reactions. Chem. Rev. 118, 4817–4833 (2018).

Xu, S.-S. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed electrochemical enantioselective reductive cross-coupling of organohalides. CCS Chem. 7, 245–255 (2025).

Huang, C., Tao, Y., Cao, X., Zhou, C. & Lu, Q. Asymmetric paired electrocatalysis: enantioselective olefin–sulfonylimine coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 1984–1991 (2024).

Liu, W.-Q. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of C(sp3)-rich amines by aminative carbofunctionalization of carbonyl compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402140 (2024).

Hu, P. et al. Electroreductive olefin–ketone coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20979–20986 (2020).

Ning, S. et al. Highly Selective electroreductive linear dimerization of electron-deficient vinylarenes. Tetrahedron 102, 132535 (2021).

Huang, B., Sun, Z. & Sun, G. Recent progress in cathodic reduction-enabled organic electrosynthesis: trends, challenges, and opportunities. eScience 2, 243–277 (2022).

Gao, S., Wang, C., Yang, J. & Zhang, J. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular reductive cyclization via electrochemistry. Nat. Commun. 14, 1301 (2023).

Gnaim, S. et al. Cobalt-electrocatalytic HAT for functionalization of unsaturated C–C bonds. Nature 605, 687–69 (2022).

Wang, T., He, F., Jiang, W. & Liu, J. Electrohydrogenation of nitriles with amines by cobalt catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e20231614 (2024).

Chang, Z. et al. Generation of hydrides or hydrogen radicals for hydrodehalogenation and deuterodehalogenation of gem-dihaloalkenes. CCS Chem. 7, 229–244 (2025).

Wu, X. et al. Intercepting hydrogen evolution with hydrogen-atom transfer: electron-initiated hydrofunctionalization of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17783–1779 (2022).

Elgrishi, N., Kurtz, D. A. & Dempsey, J. L. Reaction parameters influencing cobalt hydride formation kinetics: implications for benchmarking H2-evolution catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 239–244 (2017).

Chalkley, M. J., Garrido-Barros, P. & Peters, J. C. A molecular mediator for reductive concerted proton-electron transfers via electrocatalysis. Science 369, 850–854 (2020).

Peters, B. K. et al. Scalable and safe synthetic organic electroreduction inspired by Li-ion battery chemistry. Science 363, 838–884 (2019).

Satyanarayana, T., Abraham, S. & Kagan, H. B. Nonlinear effects in asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 456–49 (2009).

Ang, N. W. J., Oliveira, J. C. A. & Ackermann, L. Electroreductive cobalt-catalyzed carboxylation: cross-electrophile electrocoupling with atmospheric CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12842–1284 (2020).

Ackermann, L. Metalla-electrocatalyzed C–H activation by earth-abundant 3d metals and beyond. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 84–104 (2020).

Huang, W., Bai, J., Guo, Y., Chong, Q. & Meng, F. Cobalt-catalyzed regiodivergent and enantioselective intermolecular coupling of 1,1-disubstituted allenes and aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202219257 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22271227, 22471205), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515011322), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042025kf0067), and Wuhan University are greatly appreciated. We thank Dr. Shanshan Liu (Wuhan University) for the assistance with NOE experiment. We thank Dr. Qiuyan Liao from the Core Facility of Wuhan University for his assistance with X-ray crystal testing and crystallographic data analysis. We thank Dr. Gongwei Wang (Wuhan University) for the assistance with the DEMS experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L. conceived and directed the project. X.C. conducted most of the experimental studies. Y.F. and Y.T. supported performance of synthetic experiments. Q.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, X., Fu, Y., Tao, Y. et al. Enantioselective electroreductive alkyne-aldehyde coupling. Nat Commun 16, 5686 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60230-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60230-5