Abstract

The catalytic asymmetric dearomatization of naphthalenes is a pivotal strategy for generating enantioenriched three-dimensional aliphatic polycycles from flat aromatic precursors. However, achieving such transformations involving electronically unbiased naphthalenes remains a long-standing challenge. Here, we describe a silver-mediated enantioselective aza-electrophilic dearomatization approach that couples readily accessible vinylnaphthalenes in conjunction with azodicarboxylates to afford chiral polyheterocycles via formal [4 + 2] cycloaddition reactions, yielding up to 99% yield and 99 : 1 e.r. Central to the method is the formation of an aziridinium intermediate that facilitates the subsequent dearomatization of naphthalenes. A 100 mmol-scale reaction and the divergent transformation of the products into enantioenriched aliphatic polycycles highlight their synthetic utility. Mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations offer insights into the reaction mechanism and the origin of the observed enantiocontrol outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enantioenriched aliphatic polycyclic scaffolds serve as key structural cores for a broad range of drugs, materials, and biologically active natural products. These three-dimensional (3D) frameworks increase molecular complexity and profoundly impact their physicochemical properties, biological activities, and toxicity profiles, however, they engender several synthetic challenges such as multi-step sequences and pre-functionalized substrates1,2. In this regard, catalytic asymmetric dearomatization (CADA) of fused arenes offers a unique and potent strategy for directly constructing enantioenriched, structurally diverse 3D architectures3,4,5,6, enabling the generation of value-added building blocks as well as facilitating late-stage functionalization of drug candidates (Fig. 1A). While substantial progress was generally focused on electronically biased aromatic compounds, such as phenols7,8,9,10, naphthols11,12,13,14,15, naphthylamines16 and indoles17,18,19,20,21 over the past decade, the applications of naphthalenes in CADA reactions remains a significant challenge due to their pronounced aromaticity22.

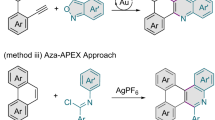

A Asymmetric dearomatization of fused arenes. B Enantioselective aza-electrophilic difunctionalization across C=C bonds. C Enantioselective aza-electrophilic dearomatization of naphthalene derivatives (this work) G, functional groups; R, R’, R”, alkyl, aryl; M, transition metals; L*, chiral ligands.

In the context of CADA reactions of naphthalenes, two primary strategies have recently emerged to promote efficient and enantioselective transformations. (1) Arenophiles-mediated dearomatization pioneered by Sarlah and co-workers23,24,25,26,27, where the dearomatization of naphthalene facilitates subsequent enantioselective transformations via transition-metal catalysis (Fig. 1A, top). (2) Substrate control, in which precisely designed precursors drive CADA reactions, offers an efficient approach (Fig. 1A, middle)22,28,29,30,31, however, it limits the substrate scope due to their challenging synthetic steps. Despite these remarkable advances, there remains a crucial demand for a direct approach to CADA reactions that is compatible with readily available naphthalenes (Fig. 1A, below), without relying on unique structures or extra operations.

Vinylarenes belong to a kind of bulk and abundant feedstocks32, such as vinylnaphthalene. It’s noteworthy that highly substituted vinylarenes could be easily accessed from bulky feedstocks via numerous methods, such as Wittig reactions33, Julia-Kocienski reactions34, Heck reactions35, Suzuki-Miyaura reactions36,37, and Still reactions38. As a result, the diverse transformations of vinylarenes into value-added products have garnered significant attention from both chemists and medicinal chemists over the past few decades. Notably, the asymmetric aza-electrophilic addition of vinylarenes provides a pivotal strategy for preparing nitrogen-containing molecules39,40,41, which is highly important in pharmaceutical and material sciences. Recently, Zhao and co-workers pioneered a copper-catalyzed enantioselective aminative difunctionalization of vinylarenes using dialkyl azodicarboxylates as electrophilic nitrogen sources (Fig. 1B)42. Cai and co-workers subsequently reported that Au(I)/NHC system could realize the enantioselective [2 + 2] cycloaddition by the utilization of azodicarboxylates and vinylarenes43. In which, the aziridinium intermediate B-1 generated via the coordination of transition-metal complexes and azodicarboxylates played a crucial role in enabling the following transformations (Fig. 1B). Inspired by these precedents, we hypothesized that the π-electrons of the aromatic ring could be perturbated by the aziridinium intermediate B-1, thereby reducing its aromaticity and facilitating the dearomatization process. However, implementing this enantioselective aza-electrophilic dearomatization presents many challenges on several fronts: (a) the competitive difunctionalization of vinylarenes across C-C π-bonds must be effectively suppressed, as prior studies have demonstrated the ease of such difunctionalization42,43; (b) the energy barrier between dearomatization and rearomatization must be sufficiently high to prevent the undesired rearomatization of the products 344,45.

As illustrated in Fig. 1C, DFT calculations revealed that the transition state TS-1, formed through the silver-catalyzed aza-electrophilic addition of vinylnaphthalene with azodicarboxylates, is more favorable than the transition state TS-2 (ΔGsol = 7.6 kcal/mol). This facilitates a 6-endo-trig process to form the dearomatization product 3, thereby motivating further exploration of the reaction in our lab. We herein report a versatile silver-catalyzed approach that is broadly applicable to the enantioselective dearomatization of vinylnaphthalenes with azodicarboxylates (Fig. 1C), enabling the direct synthesis of a diverse array of enantioenriched polyheterocycles with high regioselectivity and enantioselectivity.

Results and discussion

Identification of an effective catalytic system

We initially examined chiral phosphine ligands by selecting 1a and diethyl azodicarboxylate 2a as the model reaction in CH2Cl2 at −40 °C46. The desired dearomatization product 3a was obtained with 84% yield, despite low enantioselectivity being observed (55: 45 e.r.) using BINAP (L1). Replacing one diphenylphosphinyl group of L1 with a methoxyl group (L2) could significantly improve the enantioselectivity to 93:7 e.r. with 96% yield, the structure of which was ascertained by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Inspired by the result, various monodentate phosphine ligands were further screened. As depicted in Table 1 (entries 3–7, L3–L7), high yields were successfully obtained, but all failed to improve the enantioselectivity of the reaction (56: 44–83: 17 e.r.). N-heterocycle carbene (NHC) (L8) was also examined for the model reaction, 78% yield and 74:26 e.r. were obtained after prolonging the reaction time to 12 h (Table 1, entry 8). It’s worth noting that Au-NHC was applied for promoting enantioselective [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions in previous work43, which revealed the different chemical properties in the functionalization of alkenes between silver salts and gold salts. To our delight, reducing the reaction temperature from −40 °C to −78 °C was beneficial for this reaction, improving the enantioselectivity to 98: 5 e.r. and obtaining 97% yield (Table 1, entry 9). Subsequently, further investigations on the influences of anions of silver salts were performed (Table 1, entries 10–13), and only slightly diminished enantioselectivities were observed for 3a. In addition, conducting the electrophilic dearomatization with other solvents such as THF and toluene or changing the Lewis acids gave inferior yields and enantioselectivities.

Substrate scope

With the optimized conditions in hand, the generality of the method was first evaluated using diverse 1,1-disubstituted vinylnaphthalene 1 and azodicarboxylates 2 catalyzed by the silver complex. As shown in Fig. 2, azodicarboxylates bearing Bn, iPr, Fmoc, Troc, and MOM as protecting groups were found to serve as effective partners, furnishing the desired dearomatization products in high yields and enantioselectivities (3b–3f, up to 98: 2 e.r. and 96% yield). However, no substrate conversion and the dearomatization product were observed by GC-MS analysis when tetramethyldiazene-1,2-dicarboxamide was used under the optimized conditions. Subsequently, 2-vinylnaphthalenes with various substituents (3g–3i) were also examined, giving the corresponding products high yields and e.r. values. Furthermore, the established methods exhibited excellent functional group compatibility confirmed by a wide array of 1,1-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes (3k–3w), such as alkyl, cyclopropyl, cyclopentyl, alkenyl, halides, hydroxyl, carboxylic acids as well as trifluoromethyl groups, all gave the corresponding products with excellent results (up to 98% yield, up to 98: 2 e.r.). Notably, 1,1-diaryl alkenes with high aromaticity could also be well tolerated under standard conditions (3x–3aa), which further illustrates the general applications of asymmetric electrophilic dearomatization. In particular, this method was also compatible with the late-stage functionalization of bioactive compounds as demonstrated by the synthesis of 3ab (from Bezafibrate) and 3ac (from Indometacin). Monosubstituted vinylnaphthalenes also proved compatible under the standard conditions, affording the dearomatization products 3ad and 3ae in high yields and excellent enantioselectivities. In addition, additive studies for further exploring functional-group compatibility establish that acid, hydroxyl, phenol, thiol, ketone, amide, aryl chloride, and aryl bromide are well tolerated under the standard conditions (see the Supplementary Information Fig. 1), which fully illustrate the generality of the method.

To further explore the generality of the method in the asymmetric dearomatization of naphthalenes, 1,2-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes were then investigated under the standard conditions. As depicted in Fig. 3A, (Z)-1,2-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes bearing alkyl, ester, halides, and ether groups were well tolerated to furnish the corresponding products with high diastereoselectivities and enantioselectivities. Meanwhile, replacing (Z)-1,2-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes with (E)-1,2-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes could also furnish the corresponding products without diminution in yields and enantioselectivities, which provides a simple approach for screening the effects of absolute configurations in drug discovery in the future. Notably, trisubstituted alkenes occur widely in natural products and bioactive molecules, however, transformations involving C=C bonds for constructing C–C/X bonds remain a significant challenge due to their inherent inertness. In this silver-catalyzed system, 1,1,2-trisubstituted vinylnaphthalenes with ring strains including cyclopropane, butane, azetidine, and oxetane could be well tolerated to furnish enantio-enriched spirocycles with high yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 3C), however, 3ar and 3aw were not observed under the standard conditions by GC-MS analysis. Further investigations on the mechanism are necessary for promoting the exploration of ring-strained alkenes, which is an ongoing project in our lab. When the α-site of naphthalene was substituted with alkyl and alkynyl groups, as shown in Fig. 3D, chiral tetra-substituted stereocenters (3ax–3aab) could be efficiently constructed with high yields and enantioselectivities. However, replacing the alkyl groups at the α-site of naphthalene with aryl groups failed to realize the dearomatization reaction, and only [2 + 2] cycloaddition products were generated with moderate enantioselectivities (4a–4d), thus it further confirmed the competing TS-2 intermediate in the reaction (Fig. 1C). Based on the X-ray crystallographic analysis of the product 4a, the phenyl substituent and the naphthalene ring are not coplanar; instead, they adopt a tangential spatial conformation. Due to this spatial arrangement, we speculate that the azo-dicarboxylate encounters significant steric hindrance when attacking the α-position of the naphthalene, thereby suppressing the formation of the [4 + 2] cyclization product.

A Investigations on (Z)-1,2-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes. B Investigations on (E)−1,2-disubstituted vinylnaphthalenes. C Investigations on 1,1,2-trisubstituted vinylnaphthalenes. D Construction of tetrasubstituted stereocenters. a The reaction was carried out at −78 °C ~ rt with 1 mol% AgSbF6 and L2. b The reaction was carried out at −78 °C ~ −20 °C. Yields are for isolated and purified products. e.r. is determined by HPLC analysis. See the supplementary materials for details.

Divergent transformations and mechanistic evaluation

Further investigation of the application of the method was carried out sequentially, including the gram-scale synthesis and diverse transformations. As depicted in Fig. 4A, a gram-scale experiment using 1a and 2a was carried out at 100 mmol, yielding 31.2 g of 3a with a 91% yield and a 98: 2 enantiomeric ratio. In addition, the hydrogenation of 3a could be successfully realized by the Pd/C catalyst to give 5 under a H2 atmosphere with high enantioselectivity. Meanwhile, a neat oxidation of 3a using O2 in the air irradiated by Blue LED successfully furnished the enantioenriched heterocycle 6, and the X-ray crystallographic analysis ascertained its absolute configuration. The transformation 3u to the aliphatic polycycle 7 was also realized via an electrophilic alkene halogenation using an NBS reagent, meanwhile, the absolute configuration of 7 was determined by its X-ray crystallographic analysis.

The mechanistic underpinnings governing the efficiency of the silver-catalyzed electrophilic dearomatization are further deliberated in Fig. 4. Radical quenching experiments were initially conducted using 1a and 2a as model substrates under optimized conditions. The addition of radical quenchers such as TEMPO, BHT, or DMPO did not affect the reaction outcome, indicating that a radical pathway is likely not involved. In addition, no formation of cycloaddition product 5 was detected by GC-MS analysis when α-substituted vinylnapthalene 9 and 2a were subjected to the silver-catalyzed system, illustrating that the silver-catalyzed dearomatization was different from the previous synergistic cycloaddition reactions47. The introduction of electron-withdrawing groups across the C=C bonds negatively impacts the reaction, as no conversion was observed by GC-MS analysis when 11 or 13 were employed. This observation is likely due to the electron-deficient nature of these substrates. To further probe the mechanism of the reaction, the 31P-NMR spectroscopy analysis was then conducted. As shown in Fig. 4D, the chemical shift of L2 was observed at δ -14.14 ppm (Fig. 4D, D-1). Upon mixing AgSbF6 and L2 in CD2Cl2 at room temperature, two phosphine peaks emerged (Fig. 4D, D-2: δ 14.10 ppm, 10.75 ppm; δ 8.81 ppm, 3.79 ppm), consistent with the formation of an Ag-MOP(L2) as previously reported46,48,49. Notably, the addition of 1a did not alter the 31P-NMR chemical shift. The introduction of azodicarboxylates 2a caused a significant shift, with a new phosphine peak appearing at δ 52.96 ppm (Fig. 4D, D-4), which confirmed the coordination of Ag-MOP with 2a, but not with the alkene 1a. Further analysis of the L2/1a and L2/2a systems highlighted the essential role of AgSbF6 in the reaction (Fig. 4D, D-5,6). A new phosphine signal observed at δ 27.76 ppm in the 31P-NMR spectrum is assigned to the reaction between 1a and L2 to generate a zwitterionic intermediate (see Supplementary Information Table 1), which prevented AgSbF6 from coordinating with the phosphine ligand L2. And it was confirmed by the GC-MS analysis that no product formation or substrate conversion occurred when the reaction was performed by pre-stirring L2 and 2a before further steps. Finally, the linear effect experiments with 1a and 2a under the standard conditions revealed a strong correlation between the ee of the chiral ligand L2 and the ee of the product 3a (Fig. 4E), suggesting a first-order dependence of enantioselective dearomatization on the catalyst.

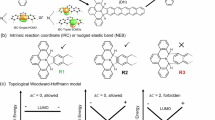

In addition, DFT calculations were carried out to elucidate the mechanisms for the Ag-mediated aza-electrophilic dearomatization reactions of 1a with azodicarboxylate, which exhibited excellent performance in the experiments (see Supplementary Information Figs. 4–9 and Supplementary Data 1). The energy profiles for the formation processes of the R- and S-product are shown in Fig. 5 (Supplementary Information, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, and Fig. 7). At the beginning of the reaction, there are two possibilities for the combination of the Ag-catalyst ([Cat-Ag]+) and reactant molecule (Sub-1 [2a] and Sub-2 [1a]). By comparing the binding energies of the two complexes, it is found that the Ag-catalyst ([Cat-Ag]+) prefers to bind to Sub-1 to form a stable intermediate structure Int0 ([Cat-Ag-Sub-1]+), which is 4.6 kcal/mol lower in energy than that of the complex of [Cat-Ag-Sub-2]+. Based on this, it is seen in Fig. 1 that the formation of the first intermediate Int0 ([Cat-Ag-Sub-1]+) is exothermic by 7.0 kcal/mol. In which, the Ag atom of [Cat-Ag]+ coordinates with the azo and carbonyl groups of 2a leading to a stable structure.

Subsequently, there are two routes for 2a to get close to 1a of Int0, as shown in Fig. 5, and generate the intermediates Int1S or Int1R. The formation of Int1 is exothermic by 0.1 kcal/mol for Int1s and endothermic by 1.3 kcal/mol for Int1R. The main reason that Int1s is 1.4 kcal/mol more stable than Int1R is the existence of one more edge-to-face (C-H…π) interaction as shown in Supplementary Information Fig. 7. For the first C-N1 bond formation process, the intermediate Int2S is formed via an energy barrier of 6.7 kcal/mol involving the bonding of the terminal alkenyl carbon atom of 1a and the N1 atom of 2a (Fig. 1). Then, the formation of the second C-N2 bond needs to undergo the cyclization process of Int2S → TS2S-3S → Int3S via an energy barrier of 4.7 kcal/mol. At the end of the process of the dearomatization of the S-product, the target product S-product is released from the catalyst [Cat-Ag]+. In this process, the dearomatization S-product is formed via the overall energy barrier of 6.7 kcal/mol involving the formation reaction of Int0 and a two-step (formation of two C-N bonds) cyclization reaction. Therein, the formation of the first C-N1 bond is the rate-limiting step.

Compared to the pathway of S-product, the formation process of R-product is different. After forming the intermediate structure of Int1R, the subsequent cyclization reaction is done in one step for the R-product, i.e., it is a synergistic reaction (Fig. 5, Supplementary Information Fig. 6 and Supplementary Information Fig. 7). This synergistic process of Int1R → Int2R via TS1R-2R has to overcome an energy barrier of 11.5 kcal/mol, which is about 4.8 kcal/mol larger than that for the formation of S-product. By comparing the intermediate structures generated in the processes (Supplementary Information Fig. 7), the weak interaction plays an important role in the stability of the key transition state structures in the pathway. There are two edge-to-face (C-H…π) interactions formed between [Cat-Ag]+ and 1a in TS1S-2S, and only one edge-to-face (C-H…π) interaction in TS1R-2R, which confirms that the silver-mediated aza-electrophilic dearomatization reaction tends to follow the formation process of the S-product. The results are consistent with the experimental data.

Furthermore, the mechanism of the [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction is also explored in this work, as shown in Supplementary Information Fig. 8 and Supplementary Information Fig. 9. Based on the intermediate structure of Int0, the second C-N2 bond formation is the process Int2S → TS2S-3’ → Int3’ via an energy barrier of 12.3 kcal/mol as shown in Supplementary Information Fig. 8. For the [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction, the second C-N2 bond formation is the key step. Compared with the overall energy barrier of the [4 + 2] cycloaddition reaction, the [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction has to overcome an energy barrier that is 5.6 kcal/mol higher due to the presence of the high tension of the four-membered ring in the transition state structure of TS2S-3’. The existence of the weak interactions is further analyzed for transition state structures of TS2S-3S and TS2S-3’, respectively. It is shown that the more favorable non-covalent interactions (edge-to-face (C-H…π) and H-bond) formed between catalyst and reactant molecules also contribute to the stability of the transition state structures.

In conclusion, the silver-catalyzed system we have developed is capable of mediating enantioselective aza-electrophilic dearomatization of readily available vinylnaphthalenes in conjunction with azodicarboxylates, yielding enantioenriched polyheterocycles with excellent enantioselectivity and efficiency under mild conditions, exhibiting outstanding functional group compatibility. Furthermore, divergent aliphatic polycycles could be generated via simple transformation, which was challenging to synthesize by traditional methods. Control experiments, linear effect investigations, and DFT calculations offered detailed insights into the mechanism, paving the way for further advancements in asymmetric dearomatization of naphthalene derivatives. Further exploration of the catalytic system in the asymmetric dearomatization reactions is ongoing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Methods

General procedure for the asymmetric dearomatization of vinylnaphthalenes: A flame-dried sealed tube was cooled to room temperature and filled with argon. To this flask was added (S) - MOP (4.7 mg, 0.01 mmol, 0.5 mol%), AgSbF6 (3.4 mg, 0.01 mmol, 0.5 mol%), and distilled CH2Cl2 (5.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15–30 min and then cooled to −78 °C. After that, 1 (2.4 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) and 2 (2.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) were added to the mixture, and the reaction was sealed with a Teflon plug stirring at −78 °C. When the reaction finished, which was monitored by TLC, the mixture was concentrated by rotary evaporation. Then the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Petroleum Ether/EtOAc) to afford the desired product 3.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information, and the data from the corresponding authors are available upon request. An X-ray crystal structure data file (CCDC 2409250 (3a), 2444389 (3af), 2409260 (4a), 2443847 (5), 2412710 (6), 2409261 (7)) has been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and is available free of charge from www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Change history

06 August 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62621-0

References

Geist, E., Kirsching, A. & Schmidt, T. sp3-sp3 coupling reactions in the synthesis of natural products and biologically active molecules. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 441–448 (2020).

Ritchie, T. J. & Macdonald, S. J. F. The impact of aromatic ring count on compound developability—are too many aromatic rings a liability in drug design?. Drug Discov. Today 14, 1011–1020 (2009).

Liu, Y.-Z., Song, H., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Cascade asymmetric dearomative cyclization reactions via transition-metal-catalysis. Nat. Synth. 1, 203–216 (2022).

Huck, C. J. & Sarlah, D. Shaping molecular landscapes: recent advances, opportunities, and challenges in dearomatization. Chem 6, 1589–1603 (2020).

Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Advances in catalytic asymmetric dearomatization. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 432–444 (2021).

Zhuo, C.-X., Zhang, W. & You, S.-L. Catalytic asymmetric dearomatization reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12662–12686 (2012).

Sun, W., Li, G. & Wang, R. Asymmetric dearomatization of phenols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 2164–2176 (2016).

Gao, X. et al. Catalytic asymmetric dearomatization of phenols via divergent intermolecular (3+2) and alkylation reactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 5189 (2023).

Dohi, T. et al. A chiral hypervalent iodine(III) reagent for enantioselective dearomatization of phenols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3787–3790 (2008).

Wu, W.-T., Zhang, L. & You, S.-L. Catalytic asymmetric dearomatization (CADA) reactions of phenol and aniline derivatives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 1570–1580 (2016).

An, J. & Bandini, M. Recent advances in the catalytic dearomatization of naphthols. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 23, 4087–4097 (2020).

Nan, J. et al. Direct asymmetric dearomatization of 2-naphthols by scandium-catalyzed electrophilic amination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2356–2360 (2015).

Wang, S.-G. et al. Asymmetric dearomatization of β-naphthols through a bifunctional-thiourea-catalyzed Michael reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14929–14932 (2015).

Egami, H. et al. Asymmetric dearomative fluorination of 2-naphthols with a dicarboxylate phase-transfer catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14101–14105 (2020).

Maji, U., Mondal, B. D. & Guin, J. Asymmetric aminative dearomatization of 2-naphthols via non-covalent N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Org. Lett. 25, 2323–2327 (2023).

García-Fortanet, J., Kessler, F. & Buchwald, S. L. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric dearomatization of naphthalene derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6676–6677 (2009).

Yu, X., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Chiral Brønsted acid-catalyzed intramolecular asymmetric dearomatization reaction of indoles with cyclobutanones via cascade Friedel-Crafts/semipinacol rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25878–25887 (2024).

Zhan, X. et al. Catalytic asymmetric cascade dearomatization of indoles via a photoinduced Pd-catalyzed 1,2-bisfunctionalization of butadienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202404388 (2024).

Huang, X.-Y., Xie, P.-P., Zou, L.-M., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Asymmetric dearomatization of indoles with azodicarboxylates via cascade electrophilic amination/aza-Prins cyclization/phenonium-like rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11745–11753 (2023).

Wang, H.-X. et al. Design of C1-symmetric tridentate ligands for enantioselective dearomative [3+2] annulation of indoles with aminocyclopropanes. Nat. Commun. 14, 2270 (2023).

Subba, P., Sahoo, S. R., Khajuria, C. & Singh, V. K. Enantioselective aminative dearomatization of indoles via electrophilic 1,6-addition of p-quinone diimides (p-QDIs). Org. Lett. 26, 4932–4937 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Gd(III)-catalyzed regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective [4+2] photocycloaddition of naphthalene derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 16982–16989 (2024).

Wertjes, W. C., Southgate, E. H. & Sarlah, D. Recent advances in chemical dearomatization of nonactivated arenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 7996–8017 (2018).

Davis, C. W. et al. Copper-catalyzed dearomative 1,2-hydroamination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407281 (2024).

Tang, C., Okumura, M., Deng, H. & Sarlah, D. Palladium-catalyzed dearomative syn-1,4-oxyamination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 15762–15766 (2019).

Wertjes, W., Okumura, M. & Sarlah, D. Palladium-catalyzed dearomative syn-1,4-diamination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 163–167 (2019).

Hernandez, L. W., Klöckner, U., Pospech, J., Hauss, L. & Sarlah, D. Nickel-catalyzed dearomative trans-1,2-carboamination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4503–4507 (2018).

Chen, W., Bai, J. & Zhang, G. Chromium-catalyzed asymmetric dearomatization addition reactions of bromomethylnaphthalenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 359, 1227–1231 (2017).

Guan, F. et al. Asymmetric dearomative cyclopropanation of naphthalenes to construct polycyclic compounds. Chem. Sci. 13, 13015–13019 (2022).

Han, X.-Q. et al. Enantioselective dearomative Mizoroki-Heck reaction of naphthalenes. ACS Catal. 12, 655–661 (2022).

Chen, M., Wang, X., Ren, Z.-H. & Guan, Z.-H. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric domino Heck/carbocyclization/Suzuki reaction: a dearomatization of nonactivated naphthalenes. CCS Chem. 3, 69–77 (2021).

Vaughan, B. A., Webster-Gardiner, M. S., Cundari, T. R. & Gunnoe, T. B. A rhodium catalyst for single-step styrene production from benzene and ethylene. Science 348, 421–424 (2015).

Byrne, P. A. & Gilheany, D. G. The modern interpretation of the Wittig reaction mechanism. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 6670–6696 (2013).

Sakaine, G., Leitis, Z., Ločmele, R. & Smits, G. Julia-Kocienski olefination: a tutorial review. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 26, e202201217 (2023).

Alisha, M., Philip, R. M. & Anilkumar, G. Low-cost transition metal-catalyzed Heck-type reactions: an overview. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 25, e202101384 (2022).

Li, B. X. et al. Highly stereoselective synthesis of tetrasubstituted acyclic all-carbon olefins via enol tosylation and Suzuki-Miyaura coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10777–10783 (2017).

Qiu, S.-Q. et al. Asymmetric construction of an aryl-alkene axis by Palladium-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211211 (2022).

Cordovilla, C., Bartolomé, C., Martinez-Ilarduya, J. & Espinet, P. The Stille reaction, 38 years later. ACS Catal. 5, 3040–3053 (2015).

Schnatter, W. F. K., Rogers, D. W. & Zavitsas, A. A. Electrophilic addition to alkenes: the relation between reactivity and enthalpy of hydrogenation: regioselectivity is determined by the stability of the two conceivable products. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 10348–10361 (2015).

Muñiz, K., Barreiro, L., Romero, R. M. & Martínez, C. Catalytic asymmetric deamination of styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4354–4357 (2017).

Smith, M. J. S., Tu, W., Robertson, C. M. & Bower, J. F. Stereospecific aminative cyclizations triggered by intermolecular aza-Prilezhaev alkene aziridination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312797 (2023).

Huang, N., Luo, J., Liao, L. & Zhao, X. Catalytic enantioselective aminative difunctionalization of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7029–7038 (2024).

Lu, Q.-T., Du, Y.-B., Xu, M.-M., Xie, P.-P. & Cai, Q. Catalytic asymmetric aza-electrophilic additions of 1,1-disubstituted styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 21535–21545 (2024).

Wu, Z. & Wang, J. A tandem dearomatization/rearomatization strategy: enantioselective N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed α-arylation. Chem. Sci. 10, 2501–2506 (2019).

Wang, B.-C. et al. Dearomatization-rearomatization reaction of metal-polarized aza-ortho-quinone methides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301592 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Efficient access to enantioenriched gem-difluorinated heterocycles via silver-catalyzed asymmetric cycloaddition reaction. ACS Catal. 14, 7267–7276 (2024).

Raghavan, R. Diaza heterocyclic compounds for phototherapy. Patent No. WO 2010/132554 A2 (2010).

Hurem, D., Moiseev, A. G., Simionescu, R. & Dudding, T. A detailed NMR- and DFT-based study of the Sakurai-Hosomi-Yamamoto asymmetric allylation reaction. J. Org. Chem. 78, 4440–4445 (2013).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Design and synthesis of TY-Phos and application in palladium-catalyzed enantioselective fluoroarylation of gem-difluoroalkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22957–22962 (2020).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 43, 539–555 (2022).

Legault, C. Y. CYLview, 1.0b; Université de Sherbrooke, 2009 (http://www.cylview.org).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22377113, 21871282, 22301309), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0590000), Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province (tsqn202306103, tsqn202306026), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFA0914502), Distinguished Young Scholars of Shandong Province (Overseas) (2022HWYQ-004), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20232509), Shandong Postdoctoral Science Foundation (SDBX2023044), Qingdao Postdoctoral Science Foundation (QDBSH20230202048), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Ocean University of China). The DFT calculation was carried out at the National Supercomputer Center in Tianjin, and the calculations were performed on Tianhe’s new-generation supercomputer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., H.W. and G.Z. conceptually directed the investigations. J.L. developed the catalytic method. J.L. and H.L. synthesized the substrates. X.Y. and M.Z. carried out DFT calculations. H.W. wrote the paper with revisions provided by the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Liu, H., Zhou, M. et al. Enantioselective aza-electrophilic dearomatization of naphthalene derivatives. Nat Commun 16, 5488 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60660-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60660-1