Abstract

Genomic architecture changes can significantly influence genome evolution and phenotypic variation within a species. Polyploidization events are thought to be one of the important catalysts for adaptation, speciation and tumorigenesis. However, little is known about the overall impact of such events on the phenotypic landscape at a population level. Here, we completely sequenced and phenotyped a large population of 1060 Brettanomyces bruxellensis yeast isolates, punctuated by multiple independent polyploidization events, notably allopolyploidization, giving rise to a highly structured population related to various anthropized ecological niches. A subgenome-aware population analysis revealed differential genome evolution between the primary and acquired genomes, with the latter showing a higher degree of conservation between isolates. Distinct phenotypic signatures were identified across major populations, with allopolyploid isolates showing an enrichment of extreme phenotypes. Genome-wide association analysis consistently revealed the substantial influence of the acquired genome of allopolyploids, with associated variants exhibiting significantly larger effect sizes than those from the primary genome. Overall, our study illustrates the profound and species-wide impact of polyploidization events on genome evolution and phenotypic diversity. It also provides a useful resource to explore the impact of allopolyploidy on adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyploidization, the acquisition of a complete set of chromosomes, is one of the most extreme mutational events observed in nature and play a major role in the evolution of species1. This type of events have been fixed multiple times across various lineages, either temporarily, as seen in the two ancient whole-genome duplications (WGD) in the vertebrate ancestor2, or permanently. Polyploid organisms, which carry more than two chromosome sets, are especially common in plants3, but also exist in animals4,5 and fungi6,7.

Such drastic mutational events enhance the evolution of genomes in multiple ways8,9,10,11,12. Allopolyploidization events, which occur after the hybridization of two species and give rise to offspring with divergent subgenomes, further enhance adaptive potential by instantly increasing genetic diversity. Hybridization also leads to abrupt genetic isolation and speciation by inducing meiotic defects13,14. The abundance of polyploidization events found in fungi15,16,17, particularly in yeasts18,19,20,21,22,23, makes them suitable models to study these evolutionary consequences. Multiple instances of polyploidization events have occurred throughout the evolutionary history of the Saccharomycotina phylum. For instance, the most studied fungal species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, underwent at least one WGD event24, and is suspected to originate from an ancient hybridization event25. Furthermore, allopolyploidization has led to rapid speciation in the Saccharomyces genus: the hybridization between S. cerevisiae and Saccharomyces eubayanus resulted in the emergence of the allotetraploid species Saccharomyces pastorianus, involved in lager beer brewing26,27,28.

The vast genomic variation caused by polyploidization has contrasting effects on phenotypic diversity within a species. Although the immediate effects of polyploidy are often detrimental - resulting in reduced fitness in plants29 and slower growth in yeast21 - polyploidy can also provide enhanced resilience under stressful conditions30,31,32. The evolutionary innovations introduced by polyploidization offer significant adaptive potential, enabling species to respond to sudden environmental changes10. Notably, in allopolyploid organisms, each subgenome may contribute distinct adaptations, thereby enhancing the ability to thrive in a broader range of environments. In synthetic allopolyploid yeast, inheritance of traits specific to each parental species were observed, such as cold tolerance or sugar consumption33. The allopolyploid Zygosaccharomyces rouxii exhibits high salt tolerance and glycerol assimilation20,34. Finally, hybridization could play a role in the emergence of pathogenic species, as illustrated several times in the Candida and Cryptococcus genus19,35,36.

Although most studies focus on specific phenotypic traits of interest between allopolyploid species and their diploid ancestors, there is a lack of population-level exploration of the broader phenotypic consequences of allopolyploidization. To understand how each subgenome influences phenotypic variation at the species level, it is now essential to have whole-genome sequencing data from large populations of allopolyploid individuals of the same species, with adequate coverage to distinguish the functional genetic variants associated with each subgenome. In this context, the budding yeast Brettanomyces bruxellensis, commonly found in various anthropogenic niches, has experienced multiple allopolyploidization events, making it an ideal model organism for studying adaptation through allopolyploidization. Despite its unidentified wild origin, the species is known to be involved in many fermentative processes. While its presence is beneficial in the production of lambic beers, kombucha and kefir37,38,39, it is a major spoiler in the production of tequila, bioethanol and especially wine, where it produces off-flavors described as horse sweat, farm or animal smell40,41. Thus, the natural population is structured into several groups, three of which have undergone different allopolyploidization events and now carry an acquired haploid genome in addition to the primary diploid one42,43. The donor species of the acquired genomes do not correspond to any of the currently known Brettanomyces species43. However, all exhibit a 4% nucleotide divergence with B. bruxellensis primary genome.

Here, we performed whole-genome sequencing and phenotyping of over a thousand Brettanomyces bruxellensis natural isolates from different ecological niches to examine the influence of allopolyploidization on the phenotypic landscape. This extensive dataset allowed us to accurately delineate the structure of the population and revealed distinct evolutionary trajectories for the primary and acquired genomes. Through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), we studied the roles and respective impact of the two genomes on various traits, including growth under several stress conditions. Our findings highlight the significant impact of the acquired genome on phenotypic variation at the population level. Ultimately, this unique resource will guide future explorations of allopolyploidy on adaptation.

Results

Genome sequence, genetic diversity, and ploidy variation

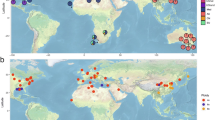

To investigate the evolution of B. bruxellensis genomes, a total of 1060 natural isolates (Supplementary Data 1) were sequenced with a short-read sequencing strategy, at a mean sequencing depth of 24X (Fig. S1). Among the sequenced isolates, 114 samples were filtered out, based on depth and quality criteria (Methods). The isolates were sampled from 30 different countries on 8 different substrates, with the majority isolated from Europe (828), on Wine substrate (842) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Data 1). We first analyzed the overall species diversity through the mapping of the whole genome reads against a reference sequence of the species, constructed from a diploid isolate44. A total of 1,470,692 SNPs were detected, leading to a nucleotide diversity of π = 0.012 ± 0.004, consistent with previous work on a smaller population45. While this diversity is much higher than the one reported for Saccharomyces cerevisiae (π = 0.003)21, several yeast species have already been reported with comparable or higher genetic diversity such as Kluyveromyces marxianus, Lachancea kluyveri and Kluyveromyces lactis (π = 0.012, π = 0.017, π = 0.028, respectively)46,47,48.

A Geographic origin of the 1060 isolates sequenced. B Ploidy estimation and presence of the Beer, Wine 1 and Teq/EtOH acquired genomes43 in 946 isolates considered in the population analysis.

Various ploidy levels have been previously reported for B. bruxellensis, with diploid, triploid and tetraploid isolates coexisting within the species, and both allo- and autopolyploids described for triploids42. The number of genomic copies corresponding to each subgenome in B. bruxellensis allopolyploids is unequal, with two copies of the primary genome combined with a single copy of the acquired genome, resulting in 2n + 1n allopolyploid organisms43. Given this high variation in ploidy in the population, we also sought to accurately estimate the ploidy for each isolate. Using an inference strategy based on allele frequencies at heterozygous loci (Methods), we found 520 (55%) diploid, 374 (40%) triploid and 10 (1%) tetraploid isolates (Fig. 1B). No reliable ploidy could be assigned for the 42 remaining isolates, which are biased towards lower sequencing depth (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 6 × 10−5, Fig. S2). To further identify allopolyploid isolates without a priori, we leveraged recent assemblies of the three different acquired genomes existing within the species43. These genome assemblies were used as references for the acquired genomes found in the previously defined Beer, Wine 1, and Tequila-Ethanol (Teq/EtOH) clades. We performed competitive mapping of the reads against primary and acquired genomes (Methods) and identified 354 isolates carrying an acquired genome, 98% being previously assigned as triploids (Fig. 1B). The Beer, Wine 1 and Teq/EtOH acquired genomes were detected in 193, 153, and 8 isolates, respectively (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Data 1).

Population structure refined through the sequencing of a thousand genomes

A structure analysis was conducted to define the genomic clusters in the population and an optimal model complexity of K = 5 ancestral populations was found (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3). We defined four major clusters encompassing 847 non-admixed isolates, that largely align with the previously defined clusters based on microsatellite analysis42 (Supplementary Data 1). The phylogeny based on genetic dissimilarities is in accordance with the population structure (Fig. 2B). The identified clusters exhibit a strong ploidy signature, as previously observed42,43, with two clusters being predominantly diploids and two clusters being exclusively allotriploid (Fig. 2C), carrying the Beer and Wine 1 acquired genomes, respectively (Supplementary Data 1). In opposition to the previous cluster names based on substrate specificity42, clusters were renamed according to their ploidy signature, as the wine substrate is the major ecological origin of all clusters. Consequently, we define the diploid cluster 1 (D1, previously designated as the Wine 3 cluster), diploid cluster 2 (D2, previously designated as the Kombucha cluster), allopolyploid cluster 1 (A1, previously designated as the Beer cluster) and allopolyploid cluster 2 (A2, previously designated as the Wine 1 cluster), which gather 457, 45, 191, and 146 isolates, respectively. The fifth ancestral population is only represented in admixed isolates previously defined as the Teq/EtOH cluster (Fig. 2A), with eight of them carrying the Teq/EtOH acquired genome. These eight isolates will be used in further analyses as the novel allopolyploid cluster 3 (A3) (Fig. 2B). Finally, while our dataset contains 59 isolates previously assigned to the Wine 2 cluster, these isolates do not represent a unique ancestral population. Rather, it is exclusively composed of isolates admixed between the D1 and D2 ancestries. Additionally, they form a monophyletic group (Fig. 2B) characterized by the presence of autotriploid isolates (Fig. 2C). Given their lack of pure ancestry, these isolates will not be considered as an independent cluster for further analyses.

A Population structure using whole genome, primary genome and acquired genome SNPs. B Neighbor-joining tree of 946 isolates based on whole genome SNPs. Branches are colored according to the redefined clusters and admixed groups. The admixed D1/D2 group corresponds to the former Wine 2 cluster. The outer ring is colored according to the ploidy. C Number of isolates and ploidy per cluster and admixed groups. D Nucleotide diversity (π) and nucleotide divergence (DXY) within and between clusters. Circle diameter and line thickness are proportional to nucleotide diversity and nucleotide divergence, respectively.

In addition to variation in ploidy, clusters also exhibit different levels of nucleotide diversity (π), with allopolyploid clusters being more diverse than non-allopolyploid clusters (Fig. 2D, Fig. S4). We observe a π value approximately an order of magnitude higher in the A1, A2 and A3 clusters compared to the D1 and D2 clusters. In addition, the nucleotide divergence between clusters is also very variable depending on the combination considered. Divergence is the highest between allopolyploid clusters, and smallest between the non-allopolyploid D1 and D2 clusters (Fig. 2D, Fig. S5). High divergence between allopolyploid clusters was expected, because allopolyploidization events that occurred in the A1, A2 and A3 clusters are believed to be independent events arising from different hybridization events43.

Genome evolution of primary and acquired subgenomes

Using a subgenome-aware approach, we sought to survey the evolution of primary and acquired genomes in allopolyploid populations. Competitive mapping permitted the segregation of sequencing reads belonging to each subgenome (Methods), which further enabled the detection of subgenome-specific SNPs. A total of 711,667 primary genome SNPs were detected in the 946 isolates, and 365,080 acquired genome SNPs were identified in the 354 allopolyploid genomes.

We first performed structure analysis on the two datasets independently and found similar clustering between genomes (Fig. 2A). Population analysis based on primary genetic variants showed an optimal number of K = 4 ancestral populations, describing the four main genomic clusters identified in the whole genome analysis, but lacking the A3 ancestry (Fig. S6). In parallel, the analysis based on acquired genetic variants revealed an optimal number of K = 3 ancestral populations, corresponding to the three distinct acquired genomes (Fig. S7). Together, these results provide a better understanding of population structure of B. bruxellensis. Four ancestries are found in the primary genome, corresponding to D1, D2, A1 and A2, with high admixture between the D1 and D2 ancestries. At the acquired genome level, three ancestries are detected, arising from the three independent allopolyploidization events previously identified43. The A1 and A2 clusters exhibit unique ancestries on both the primary and acquired genomes, suggesting that diversification of these clusters may have occurred prior to the allopolyploidization events. In contrast, the A3 cluster displays a different evolutionary history. Isolates appear to carry a primary genome admixed between D1 and D2 ancestries, similar to many diploid isolates in the population, but subsequently gained the Teq/EtOH acquired genome. Accordingly, there is no evidence for diversification of these isolates before the allopolyploidization event.

We further looked for finer structure patterns within allopolyploid clusters to study population diversification after allopolyploidization, focusing on A1 and A2 clusters due to their large sample sizes. Variable patterns were identified. While A2 isolates show a lack of population structure, A1 isolates can be classified into three well defined sub-clusters (Fig. 3A, Fig. S8). These patterns are visible on both the structure and phylogeny, and are found on primary and acquired genomes, highlighting the concomitant evolution of subgenomes following allopolyploidization. The A1 subclusters show discrepancies in their ecological origins, as most isolates originating from the beer substrate are found in the A1.1 subcluster.

A Neighbor-joining tree of 354 allopolyploid isolates based on acquired genome SNPs. The inner and outer circles represent the cluster and subcluster for each isolate, respectively. Cluster and subcluster colors apply to all the figures in this panel. B Nucleotide diversity (π) and nucleotide divergence (DXY) within and between clusters, based on primary and acquired genome SNPs. Circle diameter and line thickness are proportional to nucleotide diversity and nucleotide divergence, respectively. C Comparison of the nucleotide diversity of the primary and acquired genomes for each allopolyploid cluster over 579 non-overlapping 10 kb windows. The middle bar of the box plots corresponds to the median; the upper and lower bounds correspond to the third and first quartiles, respectively. The whiskers correspond to the upper and lower bounds 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). **** = Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 2.2 × 10−16. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons.

In addition to structure analysis, segregation of SNPs between subgenomes also allowed accurate estimation of nucleotide diversity and divergence of primary and acquired genomes. To ensure comparability between subgenomes, all diversity statistics were calculated based on the genomic regions shared between the primary and acquired genomes assemblies (45% of the primary reference genome). Nucleotide diversity within each cluster is much more similar when considering the primary genome exclusively compared to whole genome estimates (Figs. 2D, 3B, Fig. S4). A similar observation was made for nucleotide divergence: primary genome divergence is considerably less variable than whole genome divergence (Figs. 2D, 3B, Fig. S5).

While divergence between primary genomes is still significantly higher in cluster combinations containing allopolyploid clusters, this difference is strongly diminished compared to whole genome divergence (Fig. S5). This result confirms that the difference in diversity and divergence previously mentioned is mainly driven by the acquired genome. Furthermore, the divergence is much lower between primary genomes than between acquired genomes. As acquired genomes are assumed to originate from three independent hybridization events with lineages of highly divergent origins, while the primary genomes derive from the same species, such an observation is expected. Additionally, we compared the nucleotide diversity of the primary and acquired genomes within each allopolyploid cluster. We found that the diversity of the primary genome is consistently higher than that of the acquired genome (Fig. 3C). While we observe a 2-fold difference for the A3 cluster, the primary genome is 6 and 10 times more diverse than the acquired genome in the A1 and A2 clusters, respectively. A difference is also observed in linkage disequilibrium, which is higher in acquired compared to primary genomes (Fig. S9). Overall, this suggests a differential evolutionary rate between subgenomes within a same population, which is systematically biased towards the same subgenome.

A phenotypic signature of genomic clusters

To investigate the genotype-phenotype relationship in B. bruxellensis, and more precisely the impact of allopolyploidization on the phenotypic variation, we phenotyped the whole population for 38 growth traits. Growth was measured for 1056 isolates on solid media under various conditions, including carbon sources, toxic compounds, and stress conditions (Supplementary Data 2–3). Most of the traits tested exhibit a normal-shaped distribution (Fig. S10) indicating that the traits considered are complex. The prevalence of extreme phenotypes in allopolyploid isolates (Fig. S11, two-sided Fisher’s test, P < 2.2 × 10−16) suggests that allopolyploidization may be a driver of phenotypic diversification. Accordingly, a dimension-reduction analysis for all 38 traits and conducted on non-admixed isolates demonstrates a phenotypic signature specific to the A1 and A2 allopolyploid clusters (Fig. 4A). Isolates of the A3 cluster do not stand out of non-allopolyploid isolates. However, the low sample size of this population (n = 8) limits the robustness of comparisons with other clusters. The global phenotypic signature of clusters appears to be driven by a few traits, where strong phenotypic differences can be observed. For instance, there is a significant difference in growth between allopolyploid A1 and A2 isolates across the carbon sources tested, with the former cluster growing faster than the latter (Fig. 4B, Fig. S12). The same difference is significant between A1 and D1 isolates, although to a lesser extent. Such inter-cluster diversity can also be observed for sulfite resistance traits, where A2 and D1 isolates grow significantly faster than A1 isolates (Fig. 4C, Fig. S12), as previously observed on a subset of 145 isolates49.

A t-SNE based on phenotypes of non-admixed isolates for 38 growth traits. Each dot corresponds to one isolate and is colored according to its cluster. Large dots correspond to the mean value of each cluster. Heatmaps of the normalized growth across carbon sources (B) and sulfite (C) conditions. Isolates are ordered according to their position on the phylogeny (see Fig. 2B) and colored by cluster. Traits are ordered using a hierarchical clustering on the normalized phenotypes. Traits abbreviations are detailed in Supplementary Data 2.

The large number of isolates phenotyped in our study also provides the resolution to investigate phenotypic diversity within genetic clusters. The A1 sub-clusters defined above, which are highly differentiated at the genetic level, also exhibit significant phenotypic differences in 31 of 38 traits (Fig. S13). These differences are most striking across carbon sources, where A1.3 isolates grow faster in almost all conditions (Figs. S13–14). Additionally, phenotypic variation is found within the D1 cluster, where two phenotypic profiles stand out. While some isolates exhibit high sulfite resistance but slow growth across carbon sources, similar to allopolyploid A2 isolates, others have average phenotypes across all conditions (Fig. 4B, C). These profiles are linked to phylogeny, with sulfite-resistant isolates clustered on the neighboring tree (Fig. S14).

The genetic bases of trait variation at the species level

To assess the genetic architecture of the phenotypic variation in the species, a GWAS was performed. As isolates show high genetic diversity both in terms of sequence and copy number, we used whole genome SNPs and copy number variations (CNVs) as genetic markers. In total, 9368 CNVs were detected in the population based on sequencing depth on coding sequences, i.e., gene gain or loss for each of the 4684 genes. Overall, 548,535 common genetic variants (547,174 SNPs and 1361 CNVs with minor allele frequency greater than 5%, Fig. S15) were tested for association with the determined growth traits (Methods). We found 246 associations between 232 quantitative trait loci (QTL) and 35 traits, including 230 SNP-QTL and 2 CNV-QTL (Supplementary Data 4). An average number of 5 QTL per trait was detected (Fig. 5), confirming the polygenicity suggested by the normal distribution of the phenotypes (Fig. S10). We found 8 QTL shared between multiple traits, with 3 associated with at least 3 traits (Fig. 5A). These QTL are mostly associated with carbon utilization traits, because of a high correlation of growth in these conditions (Fig. 4B, Fig. S16). Across the 37 traits we tested, CNV-QTL do not have a stronger effect on the phenotypic variance than SNP-QTL. Only two CNV-QTL were detected (Fig. 5) and they do not have a larger effect size (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.6) and they are not more frequently associated than SNP-QTL (two-sided Fisher’s test, P = 0.122).

A Map of the QTL associated to studied growth traits. Black squares and red asterisks represent SNP and CNV-QTL, respectively. Each ring corresponds to one trait and is colored according to the trait category. Traits are ordered accordingly to (B). Links across traits represent shared QTL. B Number of QTL per trait. The red asterisk indicates the presence of a CNV-QTL. The abbreviation corresponding to each trait is indicated in Supplementary Data 2.

Furthermore, our results highlight the complexity of the sulfite resistance trait in B. bruxellensis natural population. Due to the detrimental effect of this species in winemaking, where sulfites are used as antimicrobial, sulfite resistance of B. bruxellensis isolates is of particular interest and has been extensively studied50,51,52,53,54. Here, 42 QTL were detected from associations with sulfite resistance traits, only one of which is associated with resistance to multiple concentrations of sulfite. The top 42 SNPs affect the coding sequence or promoter of 23 genes, two of which were found to be involved in sulfite resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (DRS2, ESBP6) (Supplementary Data 5). Additionally, 13 of these genes were affected by structural variations in an adaptative evolution experiment in presence of sulfur dioxide55, highlighting the potential effect of these genes on sulfite resistance (Supplementary Data 5). A widely studied target gene for resistance to sulfite in yeast is the sulfite efflux pump gene SSU156,57,58,59. While point mutations and copy number variation affect this gene in our collection of isolates (57 common SNPs are located within this gene and a gain of at least one copy of the gene is observed in 47% of isolates), none of these genetic variants appear to have a major impact on sulfite resistance.

Impact of primary and acquired genomes on the phenotypic variation

Finally, a major strength of our dataset is the ability to distinguish between genetic variants located in the primary (PG) and acquired (AG) genomes for allopolyploid isolates. This made it possible to study the effect of each genome on trait variation by independently performing GWAS with SNPs from the primary and acquired genomes (200,940 and 63,555 common variants, respectively, Fig. S15). A total of 131 associations (PG: 113, AG: 18) between 104 QTL (PG: 91, AG: 13) and 32 phenotypes (PG: 32, AG: 12) were detected (Supplementary Data 6). QTL located on the acquired genome (AG-QTL) have a significantly higher effect size than those located on the primary genome (PG-QTL) (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 8 × 10−5, Fig. 6A), revealing the high impact of the acquired genome on the phenotypic variation. Although this difference is striking when considering all conditions together, the impact of the acquired genome on phenotypes actually varies greatly depending on the trait tested. PG-QTL were detected in 86% of the traits (32/37), whereas only 32% of the traits (12/37) were linked to AG-QTL (Fig. 6B). For all traits, PG-QTL are more frequently associated with phenotypic variation than AG-QTL (two-sided Fisher’s test, P = 0.007, Fig. 6C). The effect of PG-QTL appears to be ubiquitous in the traits we tested, while AG-QTL affect specific traits, notably carbon sources. A proportionally equivalent number of PG and AG-QTL were detected for carbon source traits (two-sided Fisher’s test, P = 0.19, Fig. 6C), demonstrating that both genomes play a role in the phenotypic variance of these traits. Conversely, only PG-QTL were detected for sulfite resistance traits (Fig. 6B). However, PG-QTL are not significantly overrepresented for these traits, likely because of low number of QTL detected (two-sided Fisher’s test, P = 0.077, Fig. 6C). Nevertheless, this suggests a strong influence of the primary genome on the sulfite resistance trait, despite the high phenotypic diversity observed in allopolyploid isolates.

A Effect size of primary (PG) and acquired (AG) genome QTL. (**** = two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 9.3 × 10−5). The middle bar of the box plots corresponds to the median; the upper and lower bounds correspond to the third and first quartiles, respectively. The whiskers correspond to the upper and lower bounds 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). B Number of QTL per trait. Traits are grouped similarly than in Fig. 5B. The abbreviation corresponding to each trait is indicated in Supplementary Data 2. C Proportion of PG and AG-QTL associated with all traits, carbon sources and sulfite resistance traits (** = two-sided Fisher’s test, P = 5.5 × 10−3).

Discussion

Allopolyploidization represents one of the most significant mutational event occurring in nature and has been observed repeatedly in plants, animals, and fungi43,60,61. While its genomic and phenotypic effects have been studied, its impact at the population level remains largely unexplored.

Differential evolution is often observed between the distinct genomic copies of allopolyploids62. Especially, biased fractionation, which comprises unbalanced rearrangements, gene retention or genome conversion towards one genome, have been observed repeatedly in plant species63,64,65,66,67. In B. bruxellensis, biased genome conversion has been described towards the primary genome43. How subgenomes evolve at the nucleotide level is, however, difficult to tackle as it requires subgenome-aware SNPs for a population of allopolyploid organisms with sufficient sample size. The whole-genome sequencing data we generated for allopolyploid isolates offer the proper material to investigate this question. Our results revealed a higher conservation of the acquired genome in B. bruxellensis, defined by a lower nucleotide diversity and higher linkage disequilibrium. The unbalanced number of copies between subgenomes could explain part of these differences, although it is hard to quantify to which extent it affects nucleotide diversity. The high conservation may reflect a stronger purifying selection towards the acquired genome, linked to the potential adaptative advantage of carrying this genomic copy. Accordingly, previous work has shown proportionally biased expression levels towards genes located on the acquired genome, demonstrating its importance68. In plants, differences in the evolutionary rate of subgenomes has been reported. The allotetraploid cotton exhibits higher linkage disequilibrium on one subgenome than the other69, and an unbalanced evolutionary rate in reference to the respective diploid ancestor of each subgenome70,71. Additionally, biased accumulation of deleterious mutation has been demonstrated, suggesting a differential strength of selection between subgenomes72. Differences in subgenome diversity have also been reported in Brassica napus and wheat allopolyploids73,74,75.

Futhermore, allopolyploidization also contributes to the phenotypic variation of individuals. For instance, an unbalanced contribution of subgenomes to disease-resistance traits has been observed in the allotetraploid cotton70. Exploration of the phenotypic landscape of B. bruxellensis showed that allopolyploid isolates are enriched in extreme phenotype values, suggesting that allopolyploidy may lead to phenotypic diversification. Further, Genome-wide associations using subgenome-aware genetic variants allowed to tackle the unique impact of each subgenome on trait variation in allopolyploid isolates. We found evidence for a higher impact of the acquired genome variation, however spanning a narrower range of traits. These results suggest that the acquired genome impact extensively phenotypes in specific traits, perhaps related to local adaptation, which would explain a higher purifying selection on this genomic copy. Additionally, the unbalanced number of copies between subgenomes may play a role on their respective phenotypic effect, as the primary genome (present in two copies) could be more resilient to genetic variants than the single copy of the acquired genome. Although sub-genome aware GWAS are still scarce in the literature, an extensive variation map in cotton did not show any QTL subgenome bias, however limited by a small number of QTL69. Conversely, a study in wheat demonstrated a differential transcriptional variance explained by variants located on different subgenomes76. Together, these results imply that subgenome bias in the genetic architecture of traits may be common in allopolyploid species.

Finally, the dataset we generated provides a large resource to explore the consequences of allopolyploidy on the genome evolution and the genotype-phenotype relationship at the population scale. This valuable resource will pave the way for future investigations into the role of allopolyploidy in adaptation.

Methods

Isolate collection, DNA extraction and genome sequencing

The 1060 isolates included in this project were carefully selected to be representative of the B. bruxellensis whole species, based on a larger collection previously established42. All the isolate details, including ecological and geographical origins are listed in Supplementary Data 1. The geographical origin of the isolates is represented per country on Fig. 1A. The outline of the map was drawn using the open-source R package ‘maps’.

Genomic DNA was extracted from each isolate using the Omega yeast DNA kit (Life Science Products). DNA libraries were prepared from 5 ng of total genomic DNA using the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) following manufacturers’ protocols. Following quality check using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies) and quantification using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay, 4 nM of each library were pooled and run on a NextSeq 500 sequencer with paired-end 150 bp reads by the EMBL Genomics Core Facility (Heidelberg, Germany).

Reads mapping

We first mapped all sequence reads of all isolates we sequenced against the Brettanomyces bruxellensis reference sequence44. All mappings were performed using the mem algorithm of bwa 0.7.17-r118877, duplicate reads were marked and reads with a mapping quality below 30 discarded using samtools 1.1778.

Ploidy inference

For ploidy inference, we used nQuire commit a990a8879 with mapping of whole genome reads on the B. bruxellensis reference genome44. We used the functions create, denoise, and histotest to analyze the allele balance distributions and extracted which ploidies (2n, 3n, or 4n) fit best per isolate (smallest SSR and slope standard error as well as largest slope and \({R}^{2}\)). For the overall ploidy independent of whether isolates carried an acquired genome, if isolates that had the same ploidy fit best across those four metrics, the inferred ploidy was simple. If three out of four values suggested the same ploidy, we also chose that one. The remainder were interpreted as unclear ploidies.

Primary and acquired genome detection and read separation

In addition to mapping the reads to the B. bruxellensis primary reference genome, we performed a competitive mapping against both primary and acquired genomes. For this purpose, we concatenated the reference sequence with each of the Beer, Teq/EtOH, or Wine 1 acquired genome assemblies from ref. 43. Reads of each isolate were independently mapped against these three concatenated references, as described above. We considered an acquired genome to be present based on the proportion of reads that mapped to the acquired genome. If any acquired genome exceeded 11.5% of high-quality mapping reads, it was considered as being present (Fig. S17). This cutoff was determined by looking at all the isolates having a major allopolyploid ancestry (A1 or A2) and taking the lowest percentage of acquired genome reads per isolate on the corresponding genome reference. If multiple acquired genomes passed the threshold, the highest mapping percentage determined which acquired genome was considered present. Reads belonging to the primary and the acquired genomes were separated based on which sequences they mapped to during the competitive mapping.

Considering the presence of an acquired genome opened the question whether the ploidy is separated into a diploid primary and haploid acquired genome, as suggested by previous studies. We tackled this question by investigating the ploidy of the primary genome, using the method described above but using primary genome reads mapping.

SNP calling

Variant calling was performed with the mpileup and call functions of bcftools 1.1778 on bam files obtained through (i) reads mapping against the B. bruxellensis reference genome (all isolates, without competitive mapping), (ii) primary genome reads mapping against the B. bruxellensis reference genome (allopolyploid isolates, with acquired genome reads removed), (iii) acquired genome reads mapping against the respective acquired genome (allopolyploid isolates, from competitive mappings), and (iv) acquired genome reads identified from (iii), but re-mapped against the reference genome for comparability between acquired and primary genomes. The ploidy of the call command was set to haploid for acquired genome calls, otherwise diploid. The individual calls were then merged per group for subsequent analyses. Quality filters described in Table 1 were then applied to the SNP calls using bcftools 1.1778. To be kept in further analyses, allopolyploid isolates had to pass all criteria on whole, primary, and acquired genomes, resulting in 354 allopolyploid isolates kept. Non-allopolyploid isolates only had to pass whole genome filters, resulting in a total number of 946 isolates.

CNV calling

Control-FREEC v11.680 was used to assess the number of copies over 1 kb windows along the genome, taking isolate ploidy into account and using parameters: breakPointThreshold = 0.6, window = 1000, telocentromeric = 6000, step = 200, minExpectedGC = 0.3, and maxExpectedGC = 0.5. Genes with more than 50% of their length covered by a deleted or duplicated region were considered as copy number variant. CNVs were annotated as “gain” or “loss”, regardless of the number of gained or lost copies.

Structure analysis

Model-based ancestry estimation was performed on whole and primary genome SNPs using fastStructure 1.081. We ran K ∈ [1, …, 15] and chose the best fitting K by running the chooseK function, investigating both K further if maximal marginal likelihood and model components used to explain structure in data differed.

Within the three acquired genomes as well as within the associated primary genome, clusters were identified using ADMIXTURE 1.3.082, which is compatible with haploid genomes. We also ran K ∈ [1, …, 15] and chose best K as the one with the lowest cross-validation error.

Phylogeny

We reconstructed the phylogenies of the isolates’ whole, primary, and acquired genomes using the R 4.1.3 packages SNPRelate 1.28.083 and ape 5.6_284 with the filtered VCFs by creating a dissimilarity matrix using all variable SNPs and then creating a tree using the bionjs function. The trees were plotted using the R packages ggtree 3.2.085 and ggnewscale 0.4.886.

Nucleotide diversity, divergence, and linkage disequilibrium

We used pixy 1.2.5.beta187 to calculate genome-wide π and DXY values in non-overlapping 10 kb windows for the different clusters based on whole, primary, and acquired genome SNPs. Acquired genome values were calculated using the acquired genome reads mapped back against the reference genome for comparability between the main three clusters (A1, A2, A3). Windows with less than 1000 highly confident sites were discarded. Diversity values of primary and acquired genomes were calculated using regions that all primary and acquired genomes shared. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was calculated using plink v1.988 with options --r2 --ld-window-r2 0 --ld-window-kb 5000. LD calculations were performed on primary and acquired genome SNPs independently for A1, A2 and A3 isolates, considering only SNPs located in shared regions across subgenomes.

Growth traits phenotyping

A total of 1056 isolates were phenotyped for growth in 38 different conditions, including carbon sources, toxic compounds, and stress conditions (Supplementary Data 2). High-throughput phenotyping was realized as described in ref. 89 with minor modifications. Isolates were pinned onto four solid YPD matrix plates to a 384-density format using the replicating ROTOR robot (Singer Instruments) and grown 5 days at 30 °C. Then matrix plates were replicated onto phenotyping media. For each plate the reference isolate CBS2499 was replicated at least 42 times to assess noise. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 30 °C (except for 15 °C condition) and were scanned with a resolution of 600 dpi at 16-bit grayscale. Colony size was quantified in number of pixels within colony area at 0 h and 72 h using the R package Gitter90. Growth of each isolate was calculated by subtracting colony size at t = 0 h from colony size at t = 72 h. A ratio was computed for media using a specific compound. This ratio corresponds to the value in the considered media divided by the value in the reference media (YPD or YPD adjusted at pH 3.3 for sulfite-containing media).

Dimension-reduction analysis

Dimension-reduction analysis was performed on non-admixed isolates using the the tsne function of the R package M3C91. Missing phenotypes were inferred as the median phenotype for each trait.

Genome-wide association studies

Genotype-phenotype associations were performed using the mixed linear model FaST-LMM v0.6.092. The use of a linear mixed model adds a polygenic term to the regression to lower the confounding effect of population structure and relatedness on the GWAS results, which is particularly useful because of the high structure in our population. The single_snp command was used to run the associations, with parameters test_snps = bedFile, pheno = pheno_fn, count_A1 = False, map_reduce_outer = False, where bedFiles corresponds to the genetic variants data converted to the BED format with plink v1.988, and pheno_fn corresponds to a SnpData object containing the phenotype data. Since phenotype data with a normal distribution are expected by FaST-LMM, phenotypes were normalized using rank-based inverse normal transformation:

Where φ−1 is the probit function, ri is the rank of the phenotype value (average ties method) among samples and c is the Blom offset (c = 3/8). Isolates with missing phenotype were excluded from the association.

GWAS were performed using biallelic whole genome SNPs and CNVs for all isolates with both phenotypic and high-quality sequencing data. SNPs were filtered using bcftools v1.15.178 on GQ > = 20 and DP > = 5; SNPs in region of 10% extremum coverage were excluded, as well as loci and samples with more than 10 and 20% of missing genotypes, respectively. Both SNPs and CNVs with a minor allele frequency lower than 5% were filtered out, giving a total number of 547,174 high-quality SNPs, 563 gene losses and 798 gene gains passing all the filters. For each trait, a custom P value threshold was set after permuting the phenotypes 100 times. The threshold was defined as the 5th lowest percentile of the best P values obtained from the permutation, ensuring a 5% family-wise error rate. The effect size of each QTL was obtained from the EffectSize column of the FaST-LMM output. To reduce the number of false positive associations due to linkage disequilibrium between genetic variants, significant variants were clustered in groups of variants in high linkage (R2 > 0.7). R2 values were computed with plink --r2 square option88. Significant variants were clustered with the weighted average linkage clustering method (WPGMA). The most significant variant of each linkage group was kept as leading variant. Phenotypes for the copper sulfate resistance trait were not considered in the analysis because of an inflated number of false positive associations (78 QTL detected).

Additionally, GWAS were run on the allopolyploid isolates. Two independent associations were run on primary (PG) and acquired (AG) genome SNPs. To define high-quality SNPs, the same filters were applied as for whole genome SNPs, except the DP filter that was lowered to 1. Nevertheless, the MAF filter of 0.05 ensures the presence of high-quality SNPs despite the lack of depth filter. 200,940 and 63,555 SNPs passed all the filters for primary and acquired genomes, respectively. For both GWAS, whole genome SNPs were used as kinship matrix. P value thresholds were computed as previously defined. Significance thresholds of the primary genome GWAS was further multiplied by the ratio of the number of PG-SNPs to the number of AG- SNPs to enable comparison between the GWAS results. Groups of linkage were computed as described above. The methotrexate resistance trait was not considered because of an inflated number of false positive associations (227 QTL detected).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive database under accession codes PRJEB28420, PRJEB71961 and PRJEB41126. The reference primary and acquired genomes are available on Zenodo93 [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14203793].

Code availability

Codes used for data processing and analyses are available on GitHub [https://github.com/HaploTeam/1060Brett] and Zenodo93 [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14203793].

References

Van de Peer, Y., Mizrachi, E. & Marchal, K. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 411–424 (2017).

Dehal, P. & Boore, J. L. Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 3, e314 (2005).

One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative. One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants. Nature 574, 679–685 (2019).

Choleva, L. & Janko, K. Rise and persistence of animal polyploidy: evolutionary constraints and potential. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 140, 151–170 (2013).

Wertheim, B., Beukeboom, L. W. & van de Zande, L. Polyploidy in animals: effects of gene expression on sex determination, evolution and ecology. Cytogenet. Genome Re.s 140, 256–269 (2013).

Albertin, W. & Marullo, P. Polyploidy in fungi: evolution after whole-genome duplication. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 279, 2497–2509 (2012).

Todd, R. T., Forche, A. & Selmecki, A. Ploidy variation in fungi: polyploidy, aneuploidy, and genome evolution. Microbiol. Spectrum 5, 10–1128 (2017).

Soltis, D. E. & Soltis, P. S. Polyploidy: recurrent formation and genome evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 348–352 (1999).

Comai, L. The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 836–846 (2005).

Moriyama, Y. & Koshiba-Takeuchi, K. Significance of whole-genome duplications on the emergence of evolutionary novelties. Brief. Funct. Genom. 17, 329–338 (2018).

Sémon, M. & Wolfe, K. H. Consequences of genome duplication. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17, 505–512 (2007).

Selmecki, A. M. et al. Polyploidy can drive rapid adaptation in yeast. Nature 519, 349–352 (2015).

Ono, J., Greig, D. & Boynton, P. J. Defining and disrupting species boundaries in saccharomyces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 74, 477–495 (2020).

Bendixsen, D. P., Frazão, J. G. & Stelkens, R. Saccharomyces yeast hybrids on the rise. Yeast 39, 40–54 (2022).

Lu, B. C. Polyploidy in the Basidiomycete Cyathus Stercoreus. Am. J. Bot. 51, 343–347 (1964).

Nielsen, K. & Yohalem, D. S. Origin of a polyploid Botrytis pathogen through interspecific hybridization between Botrytis aclada and B. byssoidea. Mycologia 93, 1064–1071 (2001).

Ma, L.-J. et al. Genomic analysis of the basal lineage fungus rhizopus oryzae reveals a whole-genome duplication. PLOS Genet. 5, e1000549 (2009).

Suzuki, T., Nishibayashi, S., Kuroiwa, T., Kanbe, T. & Tanaka, K. Variance of ploidy in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 152, 893–896 (1982).

Morrow, C. A. & Fraser, J. A. Ploidy variation as an adaptive mechanism in human pathogenic fungi. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 339–346 (2013).

Gordon, J. L. & Wolfe, K. H. Recent allopolyploid origin of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii strain ATCC 42981. Yeast 25, 449–456 (2008).

Peter, J. et al. Genome evolution across 1,011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates. Nature 556, 339–344 (2018).

Solieri, L., Cassanelli, S. & Giudici, P. A new putative Zygosaccharomyces yeast species isolated from traditional balsamic vinegar. Yeast 24, 403–417 (2007).

Louis, V. L. et al. Pichia sorbitophila, an interspecies yeast hybrid, reveals early steps of genome resolution after polyploidization. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2, 299–311 (2012).

Wolfe, K. H. & Shields, D. C. Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome. Nature 387, 708–713 (1997).

Marcet-Houben, M. & Gabaldón, T. Beyond the whole-genome duplication: phylogenetic evidence for an ancient interspecies hybridization in the Baker’s yeast lineage. PLOS Biol. 13, e1002220 (2015).

Dunn, B. & Sherlock, G. Reconstruction of the genome origins and evolution of the hybrid lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus. Genome Res. 18, 1610–1623 (2008).

Nakao, Y. et al. Genome sequence of the lager brewing yeast, an interspecies hybrid. DNA Res. 16, 115–129 (2009).

Libkind, D. et al. Microbe domestication and the identification of the wild genetic stock of lager-brewing yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14539–14544 (2011).

Clo, J. & Kolář, F. Short- and long-term consequences of genome doubling: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Bot. 108, 2315–2322 (2021).

Chao, D.-Y. et al. Polyploids exhibit higher potassium uptake and salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis. Science 341, 658–659 (2013).

Ruiz, M. et al. Tetraploidy enhances the ability to exclude chloride from leaves in carrizo citrange seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 205, 1–10 (2016).

Yang, P.-M., Huang, Q.-C., Qin, G.-Y., Zhao, S.-P. & Zhou, J.-G. Different drought-stress responses in photosynthesis and reactive oxygen metabolism between autotetraploid and diploid rice. Photosynthetica 52, 193–202 (2014).

Peris, D. et al. Synthetic hybrids of six yeast species. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2020).

Pribylova, L., de Montigny, J. & Sychrova, H. Osmoresistant yeast Zygosaccharomyces rouxii: the two most studied wild-type strains (ATCC 2623 and ATCC 42981) differ in osmotolerance and glycerol metabolism. Yeast 24, 171–180 (2007).

Mixão, V. & Gabaldón, T. Hybridization and emergence of virulence in opportunistic human yeast pathogens. Yeast 35, 5–20 (2018).

Schröder, M. S. et al. Multiple origins of the pathogenic yeast candida orthopsilosis by separate hybridizations between two parental species. PLOS Genet. 12, e1006404 (2016).

De Roos, J. & De Vuyst, L. Microbial acidification, alcoholization, and aroma production during spontaneous lambic beer production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 99, 25–38 (2019).

Lynch, K. M., Wilkinson, S., Daenen, L. & Arendt, E. K. An update on water kefir: Microbiology, composition and production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 345, 109128 (2021).

Tran, T. et al. Microbial dynamics between yeasts and acetic acid bacteria in Kombucha: impacts on the chemical composition of the beverage. Foods 9, 963 (2020).

Suárez, R., Suárez-Lepe, J. A., Morata, A. & Calderón, F. The production of ethylphenols in wine by yeasts of the genera Brettanomyces and Dekkera: a review. Food Chem. 102, 10–21 (2007).

Wedral, D., Shewfelt, R. & Frank, J. The challenge of Brettanomyces in wine. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 43, 1474–1479 (2010).

Avramova, M. et al. Brettanomyces bruxellensis population survey reveals a diploid-triploid complex structured according to substrate of isolation and geographical distribution. Sci. Rep. 8, 4136 (2018).

Eberlein, C., Abou Saada, O., Friedrich, A., Albertin, W. & Schacherer, J. Different trajectories of polyploidization shape the genomic landscape of the Brettanomyces bruxellensis yeast species. Genome Res. 31, 2316–2326 (2021).

Fournier, T. et al. High-quality de Novo genome assembly of the dekkera bruxellensis yeast using nanopore MinION sequencing. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 7, 3243–3250 (2017).

Gounot, J.-S. et al. High complexity and degree of genetic variation in brettanomyces bruxellensis population. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, 795–807 (2020).

Friedrich, A. et al. Contrasting genomic evolution between domesticated and wild kluyveromyces lactis yeast populations. Genome Biol. Evol. 15, evad004 (2023).

Friedrich, A., Jung, P., Reisser, C., Fischer, G. & Schacherer, J. Population genomics reveals chromosome-scale heterogeneous evolution in a protoploid yeast. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 184–192 (2015).

Ortiz-Merino, R. A. et al. Ploidy Variation in Kluyveromyces marxianus Separates Dairy and Non-dairy Isolates. Front. Genet. 9, 94 (2018).

Avramova, M., Vallet-Courbin, A., Maupeu, J., Masneuf-Pomarède, I. & Albertin, W. Molecular diagnosis of brettanomyces bruxellensis’ sulfur dioxide sensitivity through genotype specific method. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1260 (2018).

Cibrario, A. et al. Brettanomyces bruxellensis phenotypic diversity, tolerance to wine stress and wine spoilage ability. Food Microbiol. 87, 103379 (2020).

G-Poblete, C., Peña-Moreno, I. C., de Morais, M. A., Moreira, S. & Ganga, M. A. Biodiversity among brettanomyces bruxellensis strains isolated from different wine regions of chile: key factors revealed about its tolerance to sulphite. Microorganisms 8, 557 (2020).

Guzzon, R. et al. Spoilage potential of brettanomyces bruxellensis strains isolated from Italian wines. Food Res. Int. 105, 668–677 (2018).

Longin, C. et al. Efficiency of population-dependent sulfite against Brettanomyces bruxellensis in red wine. Food Res. Int. 89, 620–630 (2016).

Valdetara, F. et al. Transcriptomics unravels the adaptive molecular mechanisms of Brettanomyces bruxellensis under SO2 stress in wine condition. Food Microbiol. 90, 103483 (2020).

Bartel, C. et al. Adaptive evolution of sulfite tolerance in Brettanomyces bruxellensis. FEMS Yeast Res. 21, foab036 (2021).

Goto-Yamamoto, N. et al. SSU1-R, a sulfite resistance gene of wine yeast, is an allele of SSU1 with a different upstream sequence. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 86, 427–433 (1998).

Park, H. & Bakalinsky, A. T. SSU1 mediates sulphite efflux in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 16, 881–888 (2000).

Pérez-Ortín, J. E., Querol, A., Puig, S. & Barrio, E. Molecular characterization of a chromosomal rearrangement involved in the adaptive evolution of yeast strains. Genome Res. 12, 1533–1539 (2002).

Varela, C., Bartel, C., Roach, M., Borneman, A. & Curtin, C. Brettanomyces bruxellensis SSU1 Haplotypes confer different levels of sulfite tolerance when expressed in a saccharomyces cerevisiae SSU1 Null Mutant. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 85, e02429–18 (2019).

Paterson, A. H. et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature 492, 423–427 (2012).

Premachandra, T., Cauret, C. M. S., Conradie, W., Measey, J. & Evans, B. J. Population genomics and subgenome evolution of the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis in southern Africa. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 13, jkac325 (2023).

Edger, P. P. et al. Subgenome dominance in an interspecific hybrid, synthetic allopolyploid, and a 140-year-old naturally established neo-allopolyploid monkeyflower. Plant Cell 29, 2150–2167 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Pangenome analysis reveals genomic variations associated with domestication traits in broomcorn millet. Nat. Genet. 55, 2243–2254 (2023).

Cheng, F. et al. Gene retention, fractionation and subgenome differences in polyploid plants. Nat. Plants 4, 258–268 (2018).

Liu, S. et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 5, 3930 (2014).

Schiavinato, M., Bodrug-Schepers, A., Dohm, J. C. & Himmelbauer, H. Subgenome evolution in allotetraploid plants. Plant J. 106, 672–688 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 531–537 (2015).

Jallet, A., Friedrich, A. & Schacherer, J. Impact of the acquired subgenome on the transcriptional landscape in Brettanomyces bruxellensis allopolyploids. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 13, jkad115 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Asymmetric subgenome selection and cis-regulatory divergence during cotton domestication. Nat. Genet. 49, 579–587 (2017).

Chen, Z. J. et al. Genomic diversifications of five Gossypium allopolyploid species and their impact on cotton improvement. Nat. Genet. 52, 525–533 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat. Genet. 51, 739–748 (2019).

Conover, J. L. & Wendel, J. F. Deleterious mutations accumulate faster in allopolyploid than diploid cotton (Gossypium) and unequally between subgenomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac024 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Genomic selection and genetic architecture of agronomic traits during modern rapeseed breeding. Nat. Genet. 54, 694–704 (2022).

Jordan, K. W. et al. A haplotype map of allohexaploid wheat reveals distinct patterns of selection on homoeologous genomes. Genome Biol. 16, 48 (2015).

Qian, L., Qian, W. & Snowdon, R. J. Sub-genomic selection patterns as a signature of breeding in the allopolyploid Brassica napus genome. BMC Genom. 15, 1170 (2014).

He, F. et al. Genomic variants affecting homoeologous gene expression dosage contribute to agronomic trait variation in allopolyploid wheat. Nat. Commun. 13, 826 (2022).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, giab008 (2021).

Weiß, C. L., Pais, M., Cano, L. M., Kamoun, S. & Burbano, H. A. nQuire: a statistical framework for ploidy estimation using next generation sequencing. BMC Bioinform. 19, 122 (2018).

Boeva, V. et al. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 423–425 (2012).

Raj, A., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. fastSTRUCTURE: variational inference of population structure in large SNP data sets. Genetics 197, 573–589 (2014).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Zheng, X. et al. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics 28, 3326–3328 (2012).

Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2019).

Yu, G., Smith, D. K., Zhu, H., Guan, Y. & Lam, T. T.-Y. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evolu. 8, 28–36 (2017).

Campitelli, E., Brand, T. van den & olivroy. ggnewscale: multiple fill and color scales in ggplot2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12785523 (2024).

Korunes, K. L. & Samuk, K. pixy: unbiased estimation of nucleotide diversity and divergence in the presence of missing data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 1359–1368 (2021).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet 81, 559–575 (2007).

Fournier, T. et al. Extensive impact of low-frequency variants on the phenotypic landscape at population-scale. eLife 8, e49258 (2019).

Wagih, O. & Parts, L. gitter: a robust and accurate method for quantification of colony sizes from plate images. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 4, 547–552 (2014).

John, C. R. et al. M3C: Monte Carlo reference-based consensus clustering. Sci. Rep. 10, 1816 (2020).

Lippert, C. et al. FaST linear mixed models for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods 8, 833–835 (2011).

Loegler, V. et al. Code and data for the analysis of whole-genome sequencing of 1060 Brettanomyces bruxellensis isolates. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14203793 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator grant (772505) and a French National Research Agency (ANR-22-CE21-0011-03 UnderPhe and ANR-24-CE12-0998-01PolyPhase) to J.S. In addition, J.N.R. was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grant (P500PB_203122). This work is also part of Interdisciplinary Thematic Institutes (ITI) Integrative Molecular and Cellular Biology (IMCBio), as part of the ITI 2021-to-2028 program of the University of Strasbourg, CNRS, and Inserm, supported by IdEx Unistra (ANR-10-IDEX-0002). J.S. is a Fellow of the University of Strasbourg Institute for Advanced Study (USIAS) and a member of the Institut Universitaire de France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. conceived the project. W.A., J. H. and C.M.S. provided the isolates collection. E.P. performed the phenotypic measurement experiments. C.E. extracted the DNA for sequencing. V.L. and J.N.R. performed the sequence and phenotypic data analyses. J.S. and A.F. provided theoretical support. All authors discussed the results and co-wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loegler, V., Runge, JN., Eberlein, C. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of 1,060 Brettanomyces bruxellensis isolates reveals significant phenotypic impact of acquired subgenomes in allopolyploids. Nat Commun 16, 5500 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60706-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60706-4