Abstract

Electrooxidation of pollutants at potentials near or below the thermodynamic hydrogen evolution potential offers transformative opportunities for energy-efficient pollutant valorization and diverse energy devices. However, existing catalysts suffer from rapid deactivation due to the inevitable overoxidation. Herein, we present an amorphous phosphorus-doped CoFe₂O₄ catalyst that achieves industrial-level current densities (1 A cm⁻²) at ultralow potentials (0.06, 0.65, and −0.17 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode) for hydrazine, sulfion, and borohydride electrooxidation, respectively, along with 400-hour stability at 300 mA cm⁻² in a hydrazine-assisted electrolyzer. Mechanistic studies reveal electron transfer from Co-P ligands to Co-O ligands, which enhances the involvement of Co-O ligands in low-potential electrooxidation while protecting Co-P ligands from overoxidation. Furthermore, more positive charges on Co centers lower the activation barrier for such pollutant electrooxidation. This work opens a paradigm for designing robust electrocatalysts by decoupling catalytic activity from oxidative deactivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

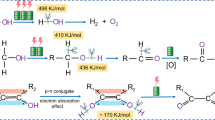

There are some pollutants in wastewater with extremely low equilibrium potentials (E0) near or below 0 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), such as hydrazine (N2H4 + 4OH− → N2 + 4H2O + 4e−, E0 = −0.33 V vs. RHE)1, sulfion (S2− − 2e− → Sx2−, E0 = 0.14 V vs. RHE)2, and borohydride (BH4− + 8OH− → BO2− + 6H2O + 8e−, E0 = −1.24 V vs. RHE)3. The electrocatalytic oxidation of these pollutants can occur at low potentials, which makes them promising alternative energy carriers for use in various energy-related applications and devices. Implementing these low-potential electrooxidation reactions (LPEOR) in diverse energy conversion systems, such as water electrolysis4 (particularly seawater electrolysis), direct liquid fuel cells5,6, CO2 reduction reactions2, electrochemical synthesis of H2O27, nitrate electroreduction reactions8, and others, is anticipated to facilitate the large-scale application of wastewater-to-energy technologies9 (Supplementary Note 1). Up to now, two types of LPEOR have been widely demonstrated: one involves the formation of electrophilic oxygen species or hydroxyl radicals, whose oxidation potential typically exceeds 1 V vs. RHE, thereby limiting the energy-saving potential10,11. The other involves direct adsorption and oxidation of substrates onto coordinatively unsaturated active metal centers, which exhibit an oxidation potential closer to the theoretical value of LPEOR12,13. Therefore, developing coordinatively unsaturated active metal sites to enable direct adsorption and oxidation of substrates is essential for substantially reducing energy consumption in various LPEOR-based energy devices14,15.

Noble metal-based catalysts generally exhibit high activity for LPEOR14,16, but their practical applications are hindered by scarcity and high costs. Developing non-precious metal-based catalysts is an inevitable choice for advancing LPEOR. However, the coordinatively unsaturated highly active sites in non-precious metal-based catalysts for LPEOR are redox-active under low potential, making them susceptible to deactivation through electrooxidation or oxidation by O217,18,19. The low-redox-potential substrate could dynamically recover the oxidized active sites to a certain extent in a timely manner3. But it remains a significant challenge to enhance the catalytic activity of LPEOR while simultaneously inhibiting the oxidative deactivation of active sites. To date, reported non-noble metal-based catalysts could operate for a maximum duration of 100 h at a current density not exceeding 100 mA cm−2. Metal phosphides, metal nitrides, metal sulfides, and metal borides all exhibit promising activity for LPEOR20,21,22. Because the lower electronegativity of these elements compared to that of oxygen enables more delocalized electrons to stabilize coordinatively unsaturated active metal sites23. This enables the metal active sites to rapidly gain and lose electrons during LPEOR, thereby exhibiting faster reaction kinetics. With metal phosphide catalysts as an example, the numerous strategies to improve the activity for LPEOR can be classified into two primary categories. One involves polarization of active centers by built-in electric fields, which can be established by heterojunctions3,24, single-atom heterojunctions25, Schottky heterojunctions26, and so on. The polarization induces electron transfer from metal centers to P atoms, which enhances the activation of substrate on metal centers but also makes P atoms more susceptible to oxidative deactivation. The other one is exposing more active metal centers by reducing catalysts27, such as via chemical reduction28 or electrochemical reduction29. However, the reduction processes increase negative charges on both the metal centers and P atoms, making P atoms more susceptible to oxidation. Therefore, developing a strategy to enhance LPEOR activity while preventing oxidative deactivation of active sites is the key to breaking the bottleneck in the practical application of LPEOR.

Due to its high stability and ease of modulation, spinel is frequently selected as a model catalyst for various electrooxidation reactions30,31,32. Here, we employed amorphization engineering to create anti-oxidizing catalytic sites on P-doped spinel oxides, which exhibit not only high catalytic activity but also robust antioxidant properties. The low-coordination environment of Co sites results in strong electron transfer between Co-P ligands and Co-O ligands. Moreover, more positive charges on Co sites enhance the adsorption and activation of substrates, while fewer electrons on P atoms endow Co-P ligands with higher resistance to oxidative deactivation. In addition, more electrons on Co-O ligands participate in LPEOR, improving the stability of Co-P ligands and the activity of active Co centers. Furthermore, the surface amorphization avoids compromising the bulk of the catalyst, which serves as a stable template for the epitaxial grafting of highly active sites. Significantly, the catalyst requires extremely low potentials of 0.06, 0.65, and −0.17 V vs. RHE to achieve a high current density of 1000 mA cm−2 with hydrazine, sulfion, and sodium borohydride as substrates, respectively. The hydrazine-assisted water electrolyzer with the catalyst serving as both cathode and anode demonstrated an exceptional stability of 400 h operation without decay at 300 mA cm−2.

Results and discussion

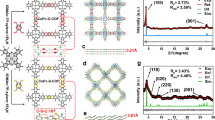

Design and realization of P-doping induced surface amorphization

The catalysts were prepared according to the experimental steps in Supplementary Fig. 1. All the catalysts present a uniform spherical morphology (Supplementary Figs. 2–5). As shown in Fig. 1a, the sample (CFO) exhibits a well-defined lattice stripe with a spacing of 0.486 nm corresponding to the (111) facet of spinel CoFe2O4, indicating its excellent crystallinity. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) reveals that the Co, Fe, and O atoms in the CFO are uniformly distributed and conform to stoichiometric ratios (Supplementary Fig. 6). The (311) and (111) facets belonging to spinel CoFe2O4 indicate the crystalline structure is retained in the P-CFO (Fig. 1b, c). And EDS results confirm the successful doping of P atoms into the P-CFO (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 7). The lattice incompleteness at the yellow dashed circles in Fig. 1c can be attributed to lattice defects on the P-CFO resulting from the P-doping process. Evidently, the introduction of P atoms into intact crystals inevitably results in a gradient distribution of P atoms. After incorporating thiourea in the preparation process, a defective layer on the d-CFO surface was constructed, as confirmed by high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images (Fig. 1e). The significant decrease in oxygen content suggests that the defect layer is predominantly composed of oxygen defects (Supplementary Fig. 8). Interestingly, an amorphous layer with a thickness of about 8 nm appears on the d-P-CFO surface, while the internal of d-P-CFO exhibits well-defined (111) facets belonging to CoFe2O4 (Fig. 1f, g). Further combined with the EDS results (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 9), it can be inferred that the P atoms in d-P-CFO are mainly present within the amorphous surface layer. This may be due to the preferential diffusion of P atoms along the surface defect layer during P-doping of d-CFO, leading to the formation of a P-doped amorphous surface on the d-P-CFO sample.

It was further verified by theoretical calculations that different catalyst structures result from P atom doping under various conditions. Crystalline and amorphous models of P-doped CoFe2O4 with oxygen vacancies (marked as c-P-CFO and a-P-CFO, respectively) were constructed using density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Supplementary Fig. 10). The energy barriers computed by the nudged elastic band method33 for diffusion of a P atom in c-P-CFO and a-P-CFO are depicted in Fig. 2a (Supplementary Data 1–3). The amorphization facilitates the diffusion of P atoms via reducing the energy barriers by half. This is likely due to the loose atomic arrangement in a-P-CFO, which allows the transfer of P atom accompanied by the movement of an adjacent metal atom (Supplementary Fig. 11). As the energy barriers for P atom diffusion in all directions are the same in the crystal structure (CFO), P-doping driven by a concentration gradient will lead to a gradient distribution of P atoms in the near-surface region (P-CFO) (Fig. 2b). Defective surface layer on the crystal structure (d-CFO) leads the incorporated P atoms to preferentially migrate in the defective layer with loose atomic arrangement rather than in the internal crystal structure (d-P-CFO) (Fig. 2c). Because the higher energy barrier for P atom diffusion in the crystal structure than that in the defective structure hinders P atoms from diffusing into the internal crystal structure. As a result, an amorphous skin enriched with P atoms can form on the surface of crystal (Fig. 2d), consistent with the structure in Fig. 1g.

a Energy variations for migration of P atoms in different structures. b, c Schematic diagram of P atom diffusion in CFO (b) and d-CFO (c). d Schematic illustration of formation of P-CFO and d-P-CFO. Source data for Fig. 2a are provided as a Source Data file.

Unique low-coordination environment of active sites

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP) results collectively indicate that in the d-P-CFO, P atoms are mainly located in the amorphous surface layer without compromising the bulk (Supplementary Figs. 12–13). Additionally, P doping has no significant effect on the catalyst’s surface pore structure (Supplementary Fig. 14). X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) verify the oxygen-deficient layer on d-CFO surface (Supplementary Figs. 15–17). Interestingly, compared with P-CFO, d-P-CFO presents higher oxidation states of Fe and Co in the XPS spectra (Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, the Co 2p XPS spectra exhibit a stronger Co-P signal for d-P-CFO, which implies a greater propensity for P atoms to coordinate with Co atoms. Correspondingly, the P 2p XPS spectrum of d-P-CFO exhibits a more pronounced M-P signal with fewer negative charges (Fig. 3c). The XPS spectra of O 1 s (Supplementary Fig. 18) show a lower binding energy of lattice oxygen in d-P-CFO, suggesting an increased electron density on O atoms. The quantitative XPS analysis revealed (Supplementary Fig. 19) that the surface of P-CFO and d-P-CFO exhibited comparable levels of O content, while more P atoms were observed on the d-P-CFO surface. This is because the amorphous surface of d-P-CFO facilitates the confinement of P atoms within the amorphous layer. The distinct signal at g = 2.004 in the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra (Supplementary Fig. 20) indicates the presence of oxygen vacancies in all samples34. The d-CFO has more oxygen vacancies than CFO, as suggested by XPS. P-doping introduces a substantial number of oxygen vacancies in P-CFO, because P-doping process is a thermal reduction of CFO by PH3. Conversely, P-doping of d-CFO leads to a small increase in oxygen vacancies. This indicates that P-doping coupled with surface amorphization avoids generation of abundant oxygen vacancies by forming low-coordinated metal active sites.

High-resolution XPS spectra of Co 2p (a), Fe 2p (b) and P 2p (c). K-edge XANES spectra of Co (d) and Fe (e) for catalysts and reference compounds. EXAFs results of Co K-edge (f) and Fe K-edge (g) for catalysts and reference compounds. h Coordination environment of active sites in different catalysts. Source data for a–g are provided as a Source Data file.

The Co K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra of different samples are compared in Fig. 3d. The oxidation state of Co in d-P-CFO is much higher than that in CoO (+2), and significantly lower than +2 in P-CFO, indicating more positively charged Co atoms in d-P-CFO, as revealed by XPS. Similarly, the increase in oxidation state of Fe is observed in d-P-CFO (Fig. 3e). The Fourier transformation of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) compares the coordination environments of active sites on d-P-CFO and P-CFO. d-P-CFO presents a significant increase in both Co-O and Co-P bond lengths (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 21, and Supplementary Table 1), indicating a looser atomic arrangement in the amorphous surface of d-P-CFO. In comparison to d-P-CFO, P-CFO exhibits a reduced oxygen coordination number due to its higher concentration of oxygen vacancies, as revealed by EPR. Raman spectra also reveal an increase in oxygen coordination sites in the amorphous layer of d-P-CFO (Supplementary Fig. 22). Interestingly, amorphization decreases the coordination number between Co and P atoms from 2.1 to 1.1, while the Co/P atomic ratio in both P-CFO and d-P-CFO is nearly identical, as revealed by ICP (Supplementary Fig. 13). This phenomenon indicates that P atoms coordinate with fewer Co atoms in d-P-CFO than in P-CFO, which is due to the low-coordinated environment induced by amorphization (Supplementary Fig. 23)35,36. The EXAFS Fourier transform presented similar results for Fe atoms, including a higher coordination number between Fe and O and a lower coordination number between Fe and P (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 24, and Supplementary Table 2). Based on the above results, the coordination environments of Co sites in P-CFO and d-P-CFO are schematically compared in Fig. 3h. The electron transfer from Co-P ligands to Co-O ligands is favored in d-P-CFO, indicating fewer electrons on P and more electrons on O involved in LPEOR. This feature could improve the catalytic activity and alleviate the overoxidation of Co-P bonds. Moreover, the upward shift of Co atom’s d-band towards EF results in a higher valence band in d-P-CFO than in P-CFO (Supplementary Fig. 25), which benefits the adsorption and activation of reactive substrates.

Enhancing electrocatalytic LPEOR performance

Iron foam (IF) substrate exhibits electrochemical inertness toward the hydrazine electrooxidation reaction (HzOR) (Supplementary Fig. 26). Both d-CFO and CFO show a limited HzOR activity, with a potential of 0.25 V vs. RHE at a current density of 100 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4a). The HzOR activities of d-P-CFO and P-CFO were significantly enhanced by introduction of the M-P bonds, exhibiting potentials of −0.05 V and 0.01 V vs. RHE at 100 mA cm−2, respectively. The P-CFO becomes passivated when the current density exceeds 300 mA cm−2, while the d-P-CFO requires a potential of only 0.06 V to achieve a high current density of 1000 mA cm−2. In comparison to commercial Pt/C, the d-P-CFO exhibits notable advantages with extremely low potential for high current densities. Moreover, the Tafel slope of 15 mV dec−1 for d-P-CFO is significantly lower than that for other catalysts (Fig. 4b), indicating the ultrafast kinetics of d-P-CFO for HzOR. We examined the improvement in energy efficiency of the HzOR within the water electrolysis system for hydrogen production. Compared to OER, HzOR exhibits an impressive reduction of 1.56 V in the input voltage at 300 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4c). Consequently, substituting OER with HzOR can significantly diminish the energy consumption for hydrogen production.

Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves (a) and Tafel slopes b of catalysts in 1 M KOH + 1 M N2H4. c Comparison of HzOR and OER polarization curves of d-P-CFO. d Linear fitting of capacitive currents of catalysts. e Comparison of performance parameters of d-P-CFO and P-CFO. f Fitted Nyquist plots of catalysts. g Stability test of d-P-CFO under 300 mA cm−2. h Comparison of potential at 1000 mA cm−2 and stability between d-P-CFO and reported HzOR catalysts. Source data for a–h are provided as a Source Data file.

The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) values of catalysts during the non-Faradaic region (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 27) are associated with their electrochemical active surface area (ECSA). Evidently, the d-P-CFO exhibits the highest Cdl value of 407 mF cm−2, signifying its superior ECSA compared to other samples. The mass activity, specific activity (Supplementary Fig. 28), and TOF values (Supplementary Fig. 29) of d-P-CFO and P-CFO at 0.06 V vs. RHE are compared in Fig. 4e. The d-P-CFO exhibits a fivefold increase in mass activity, specific activity, and TOF values compared to the P-CFO, indicating its exceptional catalytic performance for HzOR. The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) of catalysts during HzOR were examined (Supplementary Fig. 30a) and fitted with the equivalent circuit presented in Supplementary Fig. 30b. The fitted EIS results (Fig. 4f) reveal that amorphous surface leads d-P-CFO to have the lowest charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 0.39 Ω (Supplementary Fig. 31), enabling fast charge transfer during HzOR. Furthermore, the d-P-CFO presents a significantly reduced high-frequency semicircle resistance (Rf) value of only 0.05 Ω3, which indicates a large contact area at the gas-solid-liquid three-phase interface. This feature facilitates the continuous and rapid oxidation of N2H4 in the electrolyte. The LSV curves of the d-P-CFO at different scan rates during HzOR remain unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 32), demonstrating fast mass transfer and charge transfer at the electrode-electrolyte-gas three-phase interface37.

Non-noble metal catalysts may exhibit a propensity to facilitate N-N bond cleavage in HzOR, resulting in the generation of by-product NH325. The Faraday efficiencies of d-P-CFO are observed to be 96.17%, 98.58%, and 95.25% at current densities of 300, 400, and 500 mA cm−2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 33a-c). No NH3 was detected in the gas product (Supplementary Fig. 33d), indicating remarkable N2 selectivity for HzOR on d-P-CFO. To date, reported non-noble metal-based catalysts could operate for a maximum duration of 100 h at a current density not exceeding 100 mA cm−2 24. The Pt/C shows a fast decay of current density in a short time, while the d-P-CFO remains essentially unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 34). The d-P-CFO also demonstrates an exceptional catalytic stability at an industrial current density level of 300 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4g), as further supported by the SEM, TEM, XRD, XPS, ICP, and LSV characterizations of the d-P-CFO after stability test (Supplementary Figs. 35–38, Supplementary Table 3, and Supplementary Note 2). By comparing with the majority of reported HzOR catalysts, including noble metal-based catalysts (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Table 4), to our delight, the d-P-CFO stands out as the state-of-the-art one for achieving superior catalytic activity and stability at industrial-level current densities. Importantly, the d-P-CFO also exhibits outstanding catalytic activity and stability for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) (Supplementary Figs. 39–46), which enables it act as a bifunctional catalyst for LPEOR-assisted water electrolysis.

Stable low-redox-potential active sites for LPEOR

A pair of redox peaks at low potential is observed in the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of both d-P-CFO and P-CFO measured in 1 M KOH (Fig. 5a, b), indicating the presence of low-redox-potential active sites on the catalysts. The much stronger oxidation peak of d-P-CFO (108 mA cm−2) compared to that of P-CFO (76 mA cm−2) suggests a higher number of active sites for LPEOR on d-P-CFO. This can be further confirmed by the higher density of acidic sites on d-P-CFO compared to P-CFO for the adsorption and oxidation of substrates such as N2H4 (Supplementary Fig. 47). The low-potential electrooxidation reaction on HzOR catalysts containing M-P bonds has been evidenced to be the electrochemical conversion between M-P and M-POx3,38. After the introduction of low-redox-potential substrate N2H4 in a 1 M KOH solution, the CV curves of both catalysts exhibit an increase in current density for oxidation reaction. This is because N2H4 can reduce the active sites deactivated by the electrooxidation of M-P bonds and thus dynamically recover them. For d-P-CFO, the current densities of oxidation exhibit a nearly linear increase with increasing potential even at a small N2H4 concentration of 0.01 M, indicating a faster recovery rate than the oxidation rate for stabilizing the low-redox-potential active sites. In contrast, the CV curves of P-CFO exhibit an oxidation peak even at a high N2H4 concentration of 1 M, which is attributed to a limited recovery rate of oxidized M-P bonds during HzOR. Importantly, the oxidized active sites, if not dynamically recovered in time, would gradually lose their activity. As a result, P-CFO exhibits a remarkable deactivation in HzOR during four consecutive LSV tests (Supplementary Fig. 48a), with the performance of the fourth test presented in Fig. 4a. In contrast, d-P-CFO maintains HzOR activity continuously at high current densities (Supplementary Fig. 48b).

CV curves (without iR compensation) of d-P-CFO (a) and P-CFO b in different electrolyte solutions. c Comparison of HzOR performance in 1 M KOH + 1 M N2H4 of d-P-CFO before and after exposure to air for 2 h. d, In situ electrochemical Raman spectra of d-P-CFO in 1 M KOH + 1 M N2H4. LSV curves of d-P-CFO and P-CFO in 1 M NaOH + 2 M Na2S (e) and 1 M NaOH + 1 M NaBH4 (f), respectively. Polarization curves g and stability tests h of d-P-CFO for overall hydrazine-assisted water splitting (OHzS) and overall water splitting (OWS) in AEM (without iR compensation). Source data for a–h are provided as a Source Data file.

The M-P bonds in d-P-CFO can be oxidized by O2 after exposure to air for 2 h, resulting in irreversible deactivation (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 49–50). The higher O content and lower proportion of Co-P bonds confirm the overoxidation of Co-P bonds (Supplementary Fig. 51). In addition, HzOR at a high current density in a low concentration N2H4 solution also led to irreversible deactivation (Supplementary Figs. 52–53), owing to the slow recovery of active sites via N2H4-driven reduction. The in-situ Raman spectra of d-P-CFO during HzOR are presented in Fig. 5d. Three peaks prior to 700 cm−1 correspond to the stretching modes of M-O bonds39. As the potential increases, the signal of *N2H4 diminishes and the signal of *N2H3 progressively strengthens40, indicating the gradual enhancement of HzOR. The P-O signal emerges after the potential exceeds 0.2 V and gradually becomes stronger with increasing potential. This further verifies the crucial involvement of low-redox-potential active M-P bonds in the HzOR. The low-redox-potential active sites of d-P-CFO stabilized in LPEOR were further assessed in sulfion oxidation reaction (SOR) and borohydride oxidation reaction (BOR). The LSV curves in Fig. 5e, f demonstrate the exceptional performance of d-P-CFO in SOR and BOR, even at high current densities (Supplementary Tables 5–6). In contrast, deactivation of M-P bonds still occurs in P-CFO (Supplementary Figs. 54–56), when even using 1 M NaBH4 with a theoretical redox potential of −1.24 V vs. RHE. The bifunctional d-P-CFO for LPEOR and HER was further investigated by assembling an anion-exchange membrane hydrazine-assisted water electrolyzer (Supplementary Fig. 57). This hydrogen production system requires a low input voltage of 1.15 V to achieve a high current density of 1000 mA cm−2 (Fig. 5g) and can stably work for over 400 h at 300 mA cm−2 (Fig. 5h). In light of the extremely low energy consumption (energy saving by 74% as shown in Fig. 5h) and excellent stability, the practical industrial application of such LPEOR coupled hydrogen production seems to be feasible (Supplementary Fig. 58).

Synergy effect of amorphization and P-doping by computational analysis

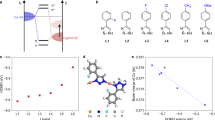

Comparing with c-P-CFO, the density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level (EF) in a-P-CFO is enhanced by near threefold due to its relatively loose atomic arrangement (Supplementary Fig. 59), thereby facilitating fast charge transfer41. The projected density of states (PDOS) for each element in c-P-CFO and a-P-CFO were analyzed, as presented in (Fig. 6a, b)42. Amorphization leads to an upward shift in the 3 d bands of Co and Fe atoms (~0.17 eV) towards EF, which benefits the adsorption and activation of substrates. Importantly, the 2p band of O atoms shifts upward significantly (0.72 eV), while the 3p band of P atoms presents a small upward shift (0.06 eV). Therefore, amorphization increases the distance between the 3d bands of metal atoms and the 3p band of P atoms, but significantly decreases the distance between the 3d bands of metal atoms and the 2p band of O atoms. M-P bonding and (M-P)* antibonding bands form when metal atoms bond with P atoms. According to the Mott-Hubbard theory, (M-P)* undergoes splitting into an occupied lower Hubbard band (LHB) and an empty upper Hubbard band (UHB)43. The increased distance between the 3d bands of metal atoms and the 3p bands of P atoms in a-P-CFO leads to an increased energy gap between the LHB and M-P bands, posing a challenge for electron extraction from the M-P band for electrooxidation (Fig. 6c, d). In contrast, the decreased distance between the 3d bands of metal atoms and the 2p band of O atoms in a-P-CFO results in greater overlap between the LHB and M-O bands, facilitating electron extraction from the M-O bands. Therefore, fewer electrons on M-P bonds and more electrons on M-O bonds in a-P-CFO could participate in LPEOR, which enhances both the stability of P-M bonds and the activity of active metal centers.

PDOS of Fe 3d, Co 3d, O 2p, and P 3p in c-P-CFO (a) and a-P-CFO (b). Schematic representation of energy band structure changes of c-P-CFO (c) and a-P-CFO (d) for LPEOR. Bader charge analysis of different atoms in c-P-CFO (e) and a-P-CFO (f) (gray, cyan, yellow and red spheres represent Co, Fe, P and O atoms, respectively). g Average Bader charge of different atoms in a-P-CFO and c-P-CFO (Inset: schematic diagram of the coupling of Co-3d and P-3p orbitals). Free energy change diagram of HzOR on surfaces of a-P-CFO (h) and c-P-CFO (i). Source data for a, b, e–i are provided as a Source Data file.

Bader charge analysis of the two structures was performed, and the charges on the surface atoms are presented in Fig. 6e, f. The average number of electrons on P atoms decreases from 0.18 |e| in c-P-CFO to 0.01 |e| in a-P-CFO (Fig. 6g). In contrast, more electrons are observed on the O atoms of a-P-CFO, as revealed by XPS and XANES. Notably, the Co atoms exhibit a significant electron loss after amorphization, implying their potential as the active metal centers for LPEOR. To validate the aforementioned assertion, the free energy variations of hydrazine oxidation reaction (HzOR) as a model LPEOR at distinct sites on c-P-CFO and a-P-CFO are calculated (Supplementary Figs. 60–61). The energy barriers on the Co site exhibit the lowest values in both structures, indicating that the Co atoms act as the active metal centers for LPEOR (Fig. 6e, f). The adsorption and activation of N2H4 is the rate-determining step (RDS) on c-P-CFO with an energy barrier of 0.67 eV. In contrast, the adsorption and activation of N2H4 on the more positively charged Co sites of a-P-CFO are thermodynamically feasible. And the energy barrier for RDS on a-P-CFO is reduced to 0.24 eV. Therefore, the amorphous P-doped oxide (a-P-CFO, i.e., d-P-CFO) possess highly active sites for exceptional LPEOR performance.

The synergy between amorphization and P-doping of spinel oxide was demonstrated to construct anti-oxidizing active Co sites, achieving both high activity and high stability for LPEOR even under high current densities. P-doping-induced surface amorphization was achieved by pre-forming a defective surface layer on crystalline spinel oxide. Low-coordinated environmental engineering leads to a strong electron transfer from Co-P ligands to Co-O ligands. More electrons on Co-O ligands and fewer electrons on Co-P ligands participate in LPEOR, which prevents the oxidative deactivation of low-redox-potential active sites and simultaneously enhances the activity of these active sites. In addition, more positively charged Co centers facilitate the adsorption and activation of substrates. Consequently, the d-P-CFO can achieve a high current density of 1000 mA cm−2 in HzOR, SOR, and BOR under extremely low potentials of 0.06, 0.65, and −0.17 V vs. RHE, respectively, surpassing the majority of previously reported LPEOR catalysts. Moreover, the d-P-CFO can act as a bifunctional catalyst in a hydrazine-assisted water electrolyzer with an exceptional stability of 400 h operation without decay at 300 mA cm−2. Importantly, based on the amorphization-induced robust catalyst, the activity and stability of LPEOR can be further enhanced by integrating with conventional strategies, such as heterojunction engineering.

Methods

Materials

Iron foam (thickness of 2 mm, pore size 110 ppi, Kunshan Tengerhui Electronic Technology), Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, aladdin, AR, 98%), Thiourea (CS(NH2)2, aladdin, AR, 99%), Nitric acid (HNO3), Hydrazine monohydrate (N2H4·H2O, 80 wt%), Pt/C (Sigma-Aldrich, 20 wt% Pt), Potassium hydroxide (KOH, AR, 85%), Sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S·9H2O, aladdin, AR, 98%), Sodium hydroborate (NaBH4, aladdin, AR, 98%), Sodium hypophosphite (NaH2PO2, aladdin, AR, 99%), Nafion D-520 dispersion (5 wt%, Dupont China Holding Co., Ltd.). Anion exchange membrane (AEM, FAA-3-50, Suzhou Sinero Technology Co., Ltd). The chemicals were utilized without additional purification.

Preparation of CFO catalyst

The CFO catalyst was synthesized on iron foam using a facile method. The iron foam was immersed in a 0.5 M HNO3 solution for 30 min to eliminate surface oxides. Subsequently, the treated iron foam was placed into a 0.1 M Co(NO3)2 solution and reacted at 90 °C for 24 h. After the reaction, the iron foam with catalyst was washed with deionized water and alcohol, and then dried in a vacuum oven at room temperature for 12 h. The weight of iron foam substrate per unit area is ~300 mg cm−2. The catalyst loading, defined as the weight fraction of the catalyst, was determined to be 4.98 wt%.

Preparation of d-CFO catalyst

The d-CFO catalyst was synthesized following a procedure analogous to that used for the CFO catalyst, with the exception that the 0.1 M Co(NO3)2 solution contained 0.125 M CS(NH2)2. The catalyst loading was 4.96 wt%.

Preparation of P-CFO catalyst

The P-CFO catalyst was synthesized by a phosphide reaction of CFO in a tubular furnace. In a typical preparation process, the CFO catalyst was positioned in a porcelain boat away from the vent, while 2.0 g of NaH2PO2 was placed in another porcelain boat upstream of the vent. Subsequently, the CFO catalyst was heated at 326 °C for 2 h with a heating speed of 2 °C min−1 in Ar atmosphere, and the P-CFO catalyst was finally obtained after cooling to room temperature in Ar atmosphere. The catalyst loading was 4.97 wt%.

Preparation of d-P-CFO catalyst

The d-P-CFO catalyst was prepared following the same procedure as that of the P-CFO catalyst, with the exception that d-CFO was used as the precursor. The catalyst loading was 4.99 wt%.

Preparation of Pt-C/IF catalyst

The commercial Pt/C catalyst (15 mg) was dispersed in 960 μL of isopropanol, followed by the addition of a Nafion solution (40 μL). The mixture was ultrasonicated for 60 min to ensure homogeneity. Subsequently, the resulting ink solution was uniformly drop-coated onto a 1 cm−2 iron foam, achieving a Pt/C loading of 5 mg cm−2.

Materials characterization

The microstructures of catalysts were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi Regulus8100, Hunan Navi New Materials Technology) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-F200). The elemental compositions of catalysts were measured by Oxford energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDX), attached to TEM equipment. The crystalline structures of catalysts were identified by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab SE) using Cu-Kɑ radiation. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha X-ray photoelectron spectrometer using Al-Kα radiation. Raman (HORIBA, LabRAM Odyssey) spectra were obtained using a DXR2 Raman Microscope with an excitation wavelength of 532 nm. The metal contents of catalysts were determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) employing an Agilent instrument. The K-edge X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) were measured at beamline 4B9A of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) in transmission mode. The NH3 temperature-programmed desorption (NH3-TPD) experiment was conducted using a PCA-1200 chemisorption analyzer equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The gas products from the cells were collected and analyzed using gas chromatography (GC, Shimadzu GC-2014C) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) operating at a constant temperature of 25 °C following the internal standard method.

Electrochemical measurements

All the electrochemical measurements were carried out in a typical three-electrode system using a Gamry Interface 1000 electrochemical workstation at room temperature (26 °C). The as-prepared catalysts were used directly as the working electrode. A Pt plate and Hg/HgO (1 M KOH) served as the counter electrode and the reference electrode, respectively. Linear scanning voltammetry (LSV) analysis was conducted with 100% ohmic potential drop (iR) correction when using a typical three-electrode system. In testing the LSV curve for the hydrogen evolution reaction, a sweep rate of 2 mV s−1 was employed. In testing the LSV curves for the hydrazine oxidation reaction, the sulfion oxidation reaction, and the borohydride oxidation reaction, the scan rate was set to 5 mV s−1. The measured potentials were normalized to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) based on the Nernst Eq. (1):

The Tafel slopes were calculated based on the Eq. (2):

Where η, a, b, and j are denoted as the overpotential, the Tafel constant, the Tafel slope, and the current density, respectively, which were derived from LSV curves.

The ECSA of each sample can be evaluated from electrochemical double capacitance (Cdl) according to the following equation:

Where Cs is the specific capacitance of the sample or the capacitance of an atomically smooth planar surface of the material per unit area under identical electrolyte conditions. Cdl in the Faradaic potential region is calculated by linear fitting. The Cs are usually found to be in the range of 0.02 ~ 0.06 mF cm−2, and it is assumed as 0.04 mF cm−2 in the calculations of ECSA. The Faradaic efficiency (FE) is calculated according to the following relationship:

Where nN2 is the amount of argon (mol), F is the Faraday constant (96500 C mol−1), Q is the total amount of charges passed through the cell, I is the current, and t is the collection time.

Turnover frequency (TOF) calculations

In this work, the Co sites in the d-P-CFO and P-CFO catalyst are considered as the active sites for HzOR. During the HzOR process, Co atoms undergo oxidation by transferring electrons to the external circuit44.

Therefore, the determination of the number of Co sites participating in HzOR can be achieved by calculating the redox charge Qredox associated with Co2+/Co3+. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves in 1 M KOH solution at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 29, where the oxidation peak areas were measured as 3.56 and 5.75 mA V for d-P-CFO and P-CFO catalysts, respectively. The calculation of Qredox can be determined by Eqs. (6) and (7).

For d-P-CFO:

For P-CFO:

The number of Co sites can be determined using Eq. (8).

Where z1 denotes the number of electrons transferred during redox at the Co sites, F is the Faraday constant, and Qredox is the redox charge.

The value of TOF can be determined by employing Eq. (9):

Where j denotes the current density at a certain overpotential, A denotes the geometric area of the electrode, Z denotes the number of electrons transferred during HzOR, and n denotes the number of active sites.

The incorporation of Eq. (8) into Eq. (9) results in the Eq. (10).

DFT calculation details

The first-principles calculations based on the Density Functional Theory (DFT) were performed within spin-polarized generalized gradient approximation (GGA). Core electron states were represented by the projector augmented-wave method45 as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)46. The wave functions are expanded using a plane-wave basis-set with an energy cutoff of 450 eV, and the convergence criteria for energy and force are set to be 10−5 eV and 0.01 eV Å−1, respectively. Based on the ICP analysis results for various catalysts, the atomic ratios within the distinct structural compositions were accurately determined. The amorphous structure of d-P-CFO is constructed by the melt-quench method47,48. Based on the defective crystal CFO structure, the initial temperature is set to 326 °C (the same temperature as the material preparation temperature) with NPT thermal ensemble state for 1000 ps, followed by another 1000 ps molecular dynamics step with target temperature of 30 °C. The final structure is geometrically relaxed before the adsorption calculation of intermediates for HzOR reaction. A 10-layer slab of crystal and amorphous CFO structure with 1.2 nm and 1.6 nm in length of a-b axis for the simulation. The Brillouin zones are sampled by 6 × 6 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack meshes49 after K-mesh test. The vacuum space of 20 Å is set to avoid the interaction between adjacent images.

Data availability

The paper and Supplementary Information contain all the data supporting the study findings. Additional information can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Xu, X. et al. Leveraging metal nodes in metal-organic frameworks for advanced anodic hydrazine oxidation assisted seawater splitting. ACS Nano 17, 10906–10917 (2023).

Teng, X. et al. Coupling electrochemical sulfion oxidation with CO2 reduction over highly dispersed p-Bi nanosheets and CO2-assisted sulfur extraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318585 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Active site recovery and N-N bond breakage during hydrazine oxidation boosting the electrochemical hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 14, 1997 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Energy-saving hydrogen production by seawater electrolysis coupling tip-enhanced electric field promoted electrocatalytic sulfion oxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6173 (2024).

Zhou, S. et al. Vacancy-rich MXene-immobilized Ni single atoms as a high-performance electrocatalyst for the hydrazine oxidation reaction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204388 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Magic hybrid structure as multifunctional electrocatalyst surpassing benchmark Pt/C enables practical hydrazine fuel cell integrated with energy-saving H2 production. eScience 2, 416–427 (2022).

Ma, C. et al. Epoxy group modified atomic Zn–N2O2 for H2O2 electrosynthesis and sulfide oxidation. ACS Catal. 14, 16522–16531 (2024).

Wang, X.-H. et al. Copper-Nickel oxide nanosheets with atomic thickness for high-efficiency sulfur Ion electrooxidation assisted nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2408834 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Advancements in electrochemical synthesis: expanding from water electrolysis to dual-value-added products. eScience, 100333 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Unlocking efficient hydrogen production: nucleophilic oxidation reactions coupled with water splitting. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404806 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. Activated Ni-OH bonds in a catalyst facilitates the nucleophile oxidation reaction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2105320 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Dual hydrogen production from electrocatalytic water reduction coupled with formaldehyde oxidation via a copper-silver electrocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 14, 525 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Combined anodic and cathodic hydrogen production from aldehyde oxidation and hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Catal. 5, 66–73 (2022).

Yu, Z. et al. Recent advances in hybrid seawater electrolysis for hydrogen production. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308647 (2024).

Wang, H.-Y. et al. Circumventing challenges: design of anodic electrocatalysts for hybrid water electrolysis systems. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203568 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Toward electrocatalytic methanol oxidation reaction: longstanding debates and emerging Catalysts. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211099 (2023).

Yu, Q. et al. Constructing three-phase heterojunction with 1D/3D hierarchical structure as efficient trifunctional electrocatalyst in alkaline seawater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205767 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Surface reconstruction of NiCoP for enhanced biomass upgrading. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 18421–18430 (2021).

Wang, A. et al. Fast-charging Zn-Air batteries with long lifetime enabled by reconstructed amorphous multi-metallic sulfide. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204247 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Progress in hydrogen production coupled with electrochemical oxidation of small molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202213328 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Energy-saving hydrogen production by seawater electrolysis coupling sulfion degradation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109321 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Ni2P/NiMoP heterostructure as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for energy-saving hydrogen production. eScience 1, 69–74 (2021).

Xiao, P. et al. A review of phosphide-based materials for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1500985 (2015).

Feng, C. et al. Lattice strain engineering of Ni2P enables efficient catalytic hydrazine oxidation-assisted hydrogen production. Adv. Mater. 35, 2305598 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. Cooperative Ni(Co)‐Ru‐P sites activate dehydrogenation for hydrazine oxidation assisting self‐powered H2 production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308800 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Hierarchical ohmic contact interface engineering for efficient hydrazine-assisted hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307979 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Partially exposed RuP2 surface in hybrid structure endows its bifunctionality for hydrazine oxidation and hydrogen evolution catalysis. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb4197 (2020).

Wei, X. et al. Local-reconstruction enables cobalt phosphide array with bifunctional hydrogen evolution and hydrazine oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 345, 123661 (2024).

Li, K. et al. Phosphorus-modified amorphous high-entropy CoFeNiCrMn compound as high-performance electrocatalyst for hydrazine‐assisted water electrolysis. Small 19, 2302130 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Importing atomic rare-earth sites to activate lattice oxygen of spinel oxides for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202415306 (2025).

Mo, Y. et al. Metal- and site-specific roles of high-entropy spinel oxides in catalytic oxidative polymerization of water contaminants. ACS Catal. 15, 5928–5942 (2025).

Ren, Y. et al. Enhanced catalytic performance of La-doped CoMn2O4 catalysts by regulating oxygen species activity for VOCs oxidation. ACS Catal. 13, 8293–8306 (2023).

Henkelman, G. et al. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Zhou, P. et al. CeO2 as an “electron pump” to boost the performance of Co4N in electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution, oxygen evolution and biomass oxidation valorization. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 325, 122364 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Engineering the coordination environment of Ir single atoms with surface titanium oxide amorphization for superior chlorine evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11152–11163 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Amorphous bismuth-tin oxide nanosheets with optimized C-N coupling for efficient urea synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13527–13535 (2024).

Wang, H.-Y. et al. Heteroatom-induced accelerated kinetics on nickel selenide for highly efficient hydrazine-assisted water splitting and Zn-hydrazine battery. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 155 (2023).

Meng, G. et al. Adsorption site regulations of [W–O]-doped CoP boosting the hydrazine oxidation-coupled hydrogen evolution at elevated current density. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 212 (2023).

Lorite, I. et al. Effects of the agglomeration state on the Raman properties of Co3O4 nanoparticles. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 1443–1448 (2012).

Lan, J. et al. Nanoporous B13C2 towards highly efficient electrochemical nitrogen fixation. Small 17, 2102814 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Enhancing the d/p-band center proximity with amorphous-crystalline interface coupling for boosted pH-robust water electrolysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203797 (2023).

Kuang, P. et al. Modulating the d-band center enables ultrafine Pt3Fe alloy nanoparticles for pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303030 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Reinforce the Co–O covalency via Ce(4f)–O(2p)–Co(3d) gradient orbital coupling for high‐efficiency oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302462 (2023).

Anantharaj, S. et al. Achieving increased electrochemical accessibility and lowered oxygen evolution reaction activation energy for Co2+ sites with a simple anion preoxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 9673–9684 (2020).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Hafner, J. Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 2044–2078 (2008).

Xue, W.-L. et al. Melt-quenched glass formation of a family of metal-carboxylate frameworks. Nat. Commun. 15, 2040 (2024).

Anantharaman, T. R. et al. Review: a decade of quenching from the melt. J. Mater. Sci. 6, 1111–1135 (1971).

Monkhorst, H. J. et al. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52374314, 52204326, 52204327), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2023RC3063), and Innovation Mover Program of Central South University (2023CXQD028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and Y.Z. conceived the idea. Y.Z., Y.L and S.W. supervised the progress of the whole project. J.C. carried out the experiments. C.S. and Y.Q. carried out the DFT calculations. J.C., Y.Z. and S.W. wrote the paper. X.W., Z.L., Z.H.L., M.W. and S.L. helped with data analysis and manuscript polishing. All the authors discussed results and provided comments during the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yubin Chen, Shao-Qing Liu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Wang, X., Sun, C. et al. Surface amorphization enables robust catalyst for industrial-level low-potential electrooxidation reactions. Nat Commun 16, 6932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62293-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62293-w