Abstract

Understanding the impact of climate change on human migration is critical for policymakers. Yet climate change can both incentivize people to migrate and reduce their ability to move, making its effect on human migration ambiguous. We propose an approach to studying migration that combines causal inference methods with cross-validation techniques to reliably estimate effects of weather on migration within and across borders. This approach highlights the key role of migrant demographics in the weather-migration relationship. We show that allowing weather effects to differ by age and education improves out-of-sample performance by a factor of five or more compared with a homogeneous effect. Demographic heterogeneity is critical in explaining this discrepancy. Projections based on our empirical estimates indicate that the effects of climate change on future cross-border migration will be an order of magnitude larger for most demographics than the average effect, but differing responses across groups largely offset one another.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In August 2022, heavy monsoon flooding led to the displacement of 33 million people in Pakistan1,2. On the other side of the Earth, Central America witnessed a highly-publicized increase in emigrants from its rural areas towards the United States, among other destinations3,4. Both events have been used as illustrations of the role that weather and climate change play in amplifying migration5. These and similar events form the basis of various policy proposals to address climate-related migration through measures meant to help people stay or to help those already on the move6,7,8. Understanding how weather and climate affect migration is key for the design and evaluation of such policies.

To understand migration decisions, it is useful to distinguish between an aspiration to move and the ability to do so9. While environmental stress can induce people to move away, it can also keep them from migrating10,11,12,13,14. For example, adverse weather might lead to movement away from exposed locations15,16,17,18, yet can also induce immobility by depleting resources necessary to migrate19,20,21. These disparate outcomes presumably depend on socioeconomic and environmental conditions. Yet the specific factors that drive different mobility outcomes in response to environmental stress remain unsettled.

Despite being of crucial importance for policy decisions, the effect of climate change on migration is still unclear. Recent studies22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 and reviews of the empirical literature30,31,32,33 offer widely varying empirical estimates of weather-induced migration. Most analyses suggest that environmental stress tends to increase out-migration in relatively middle-income locations and decrease out-migration in relatively lower-income areas32. Conversely, a few studies find that relatively low-income populations increase their local migration response under environmental stress34. Demographic characteristics have also been associated with heterogeneous mobility responses to adverse weather but with evidence mostly limited to migration within countries and with apparently contradictory findings, whereby heat stress induces either greater migration among men35 or women36 and among individuals with higher29,37,38,39 or lower education28,36.

In this paper, we combine causal inference and cross-validation methods to estimate how weather and climate influence migration within and across borders. We specifically account for differences across migrant demographics, known to affect migration decisions in general40,41. We conjecture that the net influence of weather effects on individuals’ aspirations and ability to move (which are otherwise difficult to observe directly at large scale), and thus on their migration decision, depends on their demographic characteristics10,13,40. For instance, individuals with less education, who often rely on income sources that are more dependent on weather, such as agricultural activities28, might be more incentivized to move away in response to weather shocks. Conversely, older, more established adults, who might have had more time to accumulate resources40, might be better equipped to move away in response to detrimental climate conditions. A more detailed discussion of the theoretical motivation for analyzing demographic heterogeneity in the weather-migration relationship is provided in the Supplementary Discussion.

Our estimates of demographic-specific migration responses to climate shocks demonstrate at least five times better out-of-sample predictive performance than traditional estimators that assume homogeneous effects, both within and across borders. We find major differences in migration responses across demographic groups that lead to order-of-magnitude changes in projected climate-induced migration when accounting for demographic groups. Furthermore, our results indicate that many of the seemingly contrasting results in the literature are consistent with a single global response that differs systematically by baseline climate and demographics of would-be migrants.

Migration data is from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) dataset42 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). IPUMS gives information on cross-border migration for 168 origin countries and 23 destination countries, and on within-country migration for 71 countries over the period 1988−2019. Importantly, IPUMS also provides individual-level information on migrant age, education, and sex. We take as the outcome of interest the proportion of people from a specific demographic group that move from an origin to a destination, and define 32 demographic groups according to four age categories (under 15, 15−30 years old, 30−45, above 45), four education levels (primary not completed, primary completed, secondary completed, higher education), and two sexes (male, female). In total, there are 125,109 observations of cross-border migration and 481,799 observations of within-country migration according to year, origin-destination pair, and demographic group. We conduct separate analyses for cross-border and within-country migration.

a Cross-border outmigration rates expressed as the ratio of individuals leaving per year over total origin population and averaged over the observation period, 1988-2019. Regions in white are not included in the IPUMS dataset. b Within-country outmigration rates between 1989-2019 for subnational regions. c Distribution of migrants across education, age, and sex categories, for cross-border and within-country migration. Shapefiles from IPUMS International42.

Migration patterns captured by the IPUMS dataset differ across demographics, consistent with foregoing analyses of migration40,41. The mean correlation between migration rates of different demographic groups across the same origin-destination pair, or corridor, is only 0.43 for cross-border and 0.66 for within-country moves (Supplementary Fig. S2). These low correlations presumably reflect variations in aspiration to move and ability to do so and foreshadow the potential for demographic heterogeneity in weather-mobility responses.

Weather data include daily maximum surface air temperature from the Climate Prediction Center43,44 and daily surface soil moisture from the European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative Plus Soil Moisture Project (Supplementary Fig. S3). We use soil moisture, as opposed to more-commonly used precipitation22,24,45,46,47,48,49,50, because this pairing has been shown to better predict agricultural yields51, a key determinant of mobility22. Additionally, we model heterogeneity of weather effects on migration across climate zones, using the Köppen-Geiger climate classification52 because weather effects on a variety of societal outcomes – including hypothesized determinants of migration such as agricultural productivity, GDP, and health—have been shown to systematically differ across baseline climates53,54,55.

We estimate the joint, non-linear effect of daily maximum temperature and soil moisture on migration rates across borders and within countries (Eq. (2)). Weather effects, which are measured at the origin location on the year of the move, are allowed to differ across six Köppen-Geiger climate zones (Eq. (3)). To refine our understanding of who is influenced by weather, we differentiate weather effects across demographic characteristics of migrants (Eq. (4)). In order to isolate the effects of weather variability on mobility, we specify fixed effects to account for a range of known influences upon migration rates (Methods). The effect of weather on mobility is identified through analyzing anomalies in migration rates within a demographic-specific corridor in relation to anomalies in temperature and soil moisture exposure. To interpret the estimated effects of weather variability on migration as causal, we assume that the identifying variation in weather after accounting for the fixed effects is as good as randomly assigned to the identifying variation in mobility.

For each model, in addition to evaluating the statistical significance of estimated effects, we also assess out-of-sample performance for model evaluation and selection51,55,56,57. Evaluating out-of-sample performance in addition to statistical significance helps address false-discovery issues deriving from the numerous degrees of freedom that characterize choices that can be made by individual researchers in conducting causal inference analysis58. Note that tests of predictive performance and statistical significance make distinct assumptions, including regarding the distribution of the data, and provide partially distinct information. How best to combine these two approaches to conduct evaluations is an active area of research59, and we simply report both metrics.

We evaluate out-of-sample performance on variations in migration and weather observations, after removing variations associated with fixed effects involving time, location, demographics, and geographic and cultural proximity. Using this identifying variation, we then conduct 10-fold cross-validation with performance calculated on the withheld folds as the coefficient of determination (R2). This fraction of identifying variation in migration rates explained by weather variables is computed both with and without interacting them with demographic and geographic controls51. If demographic heterogeneity in migration response is supported by the data, models including interactions of weather variables with demographic indicators should present a higher performance than models without such interactions. Whereas in-sample R2 is always positive and increases with the inclusion of additional covariates, the out-of-sample R2 that we compute can either increase or decrease with additional model complexity and becomes negative if performance is worse than a model predicting a constant mean value. This approach gives an unbiased estimate of the fraction of variation in historical migration anomalies that can be attributed to weather variations and guards against overfitting our model33,60,61.

Results

Demographics are key for understanding weather-driven migration

Instead of solely inquiring into how many people move in response to weather and climate variations, we assess how many of whom respond. To that aim, we estimate and evaluate out-of-sample a series of empirical models that do or do not allow migration responses to weather variability to differ by individual-level migrant demographics (Methods). Results of the cross-validation exercise are shown in Fig. 2a for cross-border migration and Fig. 3a for within-country migration. Estimated effect sizes, statistical significance, and full model in-sample R2 are given in Supplementary Tables S1 for cross-border migration and S2 for within-country migration.

a Out-of-sample performance (R2) predicting identifying variation in cross-border migration with weather shocks. Models include weather variables in cubic form; T stands for temperature, S for soil moisture. Interactions of weather variables with origin climate are indicated as climate zone, and added interaction of weather variables with demographic characteristics are indicated according to age, education, sex and their various combinations. A model using randomly shuffled weather variables is indicated by placebo. Box plots show the distribution of performance over 20 seeds, representing the median, upper and lower 25% values (box), and the upper and lower adjacent values (whiskers). b, c Cross-border bilateral migration rate response to temperature variability (red), and (d−e) to soil moisture variability (green). Response magnitudes are for a change of 1 day in the year relative to 18∘C or 0.18 cm3 of water per cm3 of soil. b−d Average responses differentiated by age (columns) and education (rows) (from model T,S*(age + edu)). c−e Average responses differentiated by climate zone (from model T,S*climate zone). Effects for each age, education, and climate zone combination (from model T,S*(climzone + age + edu)) are plotted in Supplementary Fig. S5. Dashed gray line shows homogeneous response across demographics and climate zones for comparison. Shading shows the 90% confidence interval for each response allowing for demographic heterogeneity. Histograms show the distribution of daily maximum temperature and soil moisture over origin countries and years when migration observations are available, with outliers winsorized for display to their 1 and 99 percentiles.

a Out-of-sample performance (R2) predicting identifying variation in within-country migration with weather shocks. b Within-country bilateral migration rate response to temperature variability in the tropical zone, and (c) to soil moisture in the dry-hot zone. Labels and conventions follow those in Fig. 2.

We find that allowing the weather effect on migration to differ by age, education, and climate zone yields the best performing model of cross-border migration rates. The full model, including fixed effects, gives an in-sample R2 of 0.875 and displays statistically significant effects for temperature on young and older adults with lower levels of education, and for soil moisture on most age groups (p < 0.05). Moreover, the model gives a positive out-of-sample R2 of 0.004 (uncertainty range of 0.003-0.004), indicating that weather explains 0.4% of variation in cross-border migration flows after accounting for fixed effects. Weather shocks are a noteworthy, albeit minor, predictive driver of cross-border migration. Geographic and cultural proximity captured by the model’s fixed effects plays a much more dominant role in explaining historical migration rates. If a simpler specification using homogeneous response across demographics and baseline climate is instead used, the results explain 12 times less identifying variation in migration rates out-of-sample (R2 = 0.0003 [0.0002;0.0004]) and are statistically insignificant. Differentiation by sex adds no predictive performance. To check that out-of-sample performance is not erroneously inferred, we assess the performance of a placebo model. Specifically, we apply the best performing model including interactions with age, education, and climate zone to weather observations that are randomly shuffled across years and locations, in which case cross-validation then produces negative out-of-sample performance, as expected for a model fit to uninformative explanatory variables.

Within-country migration models perform similarly to those for cross-border migration, with one exception. Here, the best out-of-sample performing model allows weather effects on migration to differ by age and education distinctly within each climate zone, whereas the best performing model of cross-border migration has the same heterogeneity by age and education across all climate zones. Quantitatively, 1% of within-country migration is explained by weather variations, or an out-of-sample R2 of 0.010 [0.010-0.010]. Again, the full model in-sample R2 including fixed effects is much larger, with a value of 0.855. Differentiation by sex again adds no performance, despite overall differences in within-country migration rates by sex (Fig. 1c). As for cross-border migration, assuming a homogeneous response across demographics and baseline climate zones gives a much smaller R2 of 0.002 [0.002;0.002], or a 5 times smaller performance than the heterogeneous model. The fact that our best-performing model contains climate-dependent demographic specificity may reflect the higher number of within-country observations available for constraining the model, the more geographically precise representation of origin climate zone, or that drivers of within-country migration are more determined by baseline climate.

We replicate the results of two published studies of weather-related migration22,24 in order to examine if the smaller out-of-sample performance of our model, when not including demographic heterogeneity in migration response, generalizes to other studies. Both studies are featured in the meta-analysis mentioned in the introduction32 and are selected on the basis of their results being fully replicable using code and data made immediately publicly available. Cai et al. (2016)22 report that exposure to high temperatures increases cross-border migration out of the most agriculturally-dependent countries, whereas Cattaneo and Peri (2016)24 find that higher temperatures increase migration rates in relatively middle-income countries but decrease migration rates in relatively poor countries. We first reproduce the results of both studies using their data and reported preferred specifications (Supplementary Table S3) and then apply cross-validation analyses (see Supplementary Fig. S4). For cross-border migration, the specification by ref. 22 displays substantially smaller out-of-sample performance as compared with our model (R2 = 0.0001 [0.0000;0.0002]), and the specification by ref. 24 gives negative out-of-sample performance (R2 = − 0.030 [-0.065;-0.002]). For within-country migration, the specification by ref. 24 using urbanization rates as a proxy for rural-urban moves gives an out-of-sample performance marginally higher than our preferred model but with wider confidence intervals that span zero, R2 = 0.012 [-0.008;0.027]. Ref. 22 do not investigate within-country migration.

Heat and dryness effects on cross-border moves differ by age

We plot response curves associated with the best performing model of cross-border migration in Fig. 2b–e. For readability, average weather effects per age and education are displayed in panels (b) and (d), and average weather effects per climate zone in panels (c) and (e). The estimated effects for each age, education, and climate zone combination are plotted in Supplementary Fig. S5. In accordance with our log-linear empirical model, all results are reported as percent changes from baseline migration rates, not as percentage of the overall population. For example, an increase from 0.01%/yr of the population migrating to 0.02%/yr is reported as a 100% increase in migration rate. The influence of weather on changes in migration rates are reported as the effect of 1 day of temperature or soil moisture at either their 1st or 99th percentile daily value relative to median conditions.

We find that the significance, magnitude, and direction of the weather effect on cross-border migration varies across education, age, and baseline climate zone. Heat and dryness decrease migration of the youngest population with lowest levels of education but increases migration of older, adults with little education (p < 0.01 for each). For example, one day of exposure to 99th percentile temperature as opposed to the median, i.e., 36∘C versus 18∘C, decreases migration rates of children by 0.5% and increases migration rates of older adults with primary education by an equal but opposite amount. Conversely, migration rates of adults with high levels of education are little affected by weather. These results are consistent with weather stress increasing the desire to leave a location for individuals with less education, whose income sources might be more dependent on weather; but where only adults above 30 that presumably have more accrued resources are able to move. Heat decreases movement across all climate zones, with relatively stronger effects in dry-cold, continental, and tropical areas, and dryness increases migration, particularly in dry-hot climates. As follows from the anti-correlation in weather effects across demographics, omission of demographics gives results with negligible sensitivity to weather (dashed gray line in Fig. 2b–e).

Heat increases internal moves of those with higher education levels in some climates

Turning to within-country migration, response curves associated with the model performing best out-of-sample are displayed in Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. S6. In contrast to cross-border migration, here the best-performing model allows for interactive, rather than additive, effects between baseline climate and demographics on the weather-migration relationship. We find substantial heterogeneity in migration response to weather variability across age and education as a function of climate zone.

As a first illustration of the richness of weather-migration relationships for within-country moves, in tropical zones (Fig. 3) heat increases migration of those with higher education levels (p < 0.001) but has no significant nor substantial effect on migration of those with lower education levels. Warming from 30∘C to 39∘C for 1 day in the tropical zone increases migration rates of individuals with higher education by 0.4–0.5% across age groups but does not significantly nor substantially change migration rates of individuals with primary education or less. Temperate and dry-cold zones display a similar pattern. Like for cross-border migration, these results are consistent with an explanation of weather extremes making it more difficult to move to another part of the country for the most vulnerable. Again, little to no weather effect is identified if migration responses are not resolved according to demographic characteristics (dashed gray lines in Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. S6).

Pointing to a different set of effects, both dryness and sodden conditions (possibly indicating flooding) increase migration relative to moderate soil moisture in dry-hot areas. While the effect of flooding is relatively homogeneous across demographic groups, the effect of dryness is stronger for individuals with lower education levels (0.6% increase for drying from 0.18 to 0.05 cm3 of water per cm3 of soil) and weaker for older individuals with higher education levels (0.3% increase for the same drying). In tropical and temperate zones, sodden conditions also increase migration rates of those with lower education levels, whereas those with higher education levels have a weaker or opposite response. These results indicate that extremes in water availability can increase the aspiration to move by acting as a push factor for people with less resources. A notable example of this can be found in Kenya, which in 2008−2010 suffered a severe drought that crippled agricultural and pastoral production. The annual migration rate from the rural Eastern district, located in a dry-hot area, to urban Nairobi increased by a factor of six during this drought period, going from 0.2% to 1.2% per year of the district’s population (Supplementary Fig. S7). 78% of the increase in number of migrants were associated with people having little education. An assessment led by the Kenyan Ministry of Finance concluded that the drought compelled migration out of agricultural areas on account of hunger and reduced household incomes62. This migration response within Kenya is qualitatively in line with the prediction given by our model, albeit the effect is at the 99th percentile of the coverage interval of the estimated response.

Climate change and migration: who, not just how many

To illustrate the implications of these results in the context of climate change, we use the trained empirical model as a basis for projections of cross-border migration patterns conditional on simulations of climate change over the 21st century. We project these relationships holding other drivers of migration fixed, a common50,51,54 yet major simplification that facilitates interpretation and contextualization of the empirical results. We compute the change in migration rates resulting from changes in local weather variables between today and the end of the century, as projected by global climate models under the 6th phase of the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project (CMIP6). Projections are conducted following a medium scenario of climate change and socioeconomic development (SSP2-4.5). In the Methods section, we provide additional information on how we validate and tune our empirical model for projection (Supplementary Figs. S8–S9).

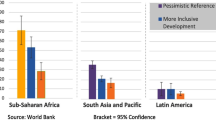

Projected age- and education-specific migration patterns respond much more strongly to climate change as represented by SSP2-4.5 when accounting for demographics (Fig. 4). Instead of yielding changes in migration rates of [ − 5%; 1%] by end-of-century (2015–2035 vs. 2080–2100), climate change is found to affect corridor migration rates by [ − 31%; + 26%], with opposite effects across demographics. Older adults with lower education levels migrate substantially more across borders, while the youngest with lowest education levels move less under climate change. Effects of more intense climate change (SSP3-7.0) on migration amplify this pattern (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Distribution of change in migration rates under projected climate change between end of century and today, consistent with a medium scenario (SSP2-4.5), over available migration observations (corridor by age by education). Results when allowing the migration response to differ by demographics (dark red), and when not (light pink), along with their mean values across demographic groups (dashed vertical lines). Demographic categories follow those in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Our results show that migration responses to weather are highly dependent upon demographic characteristics. At some level, this result is no surprise given that migration decisions in general are widely documented to vary across demographic characteristics40,41. Nevertheless, accounting for such differences across demographics helps reconcile prior contradictory findings in the climate migration literature. When accounting for age- and education-specific responses, we find that weather and climate explain a share of variance that is, while still small, 12 times greater across borders and 5 times greater within countries than when the climate-migration relationship is assumed to be uniform across demographic characteristics and baseline climate. The uncovered importance of demographics indicates that weather variability affects both the incentives and the ability to migrate.

Beyond highlighting the key role of demographics in understanding historical effects of weather on migration, cross-validation shows that models accounting for demographic-specific effects can be used to project future migration responses. We hasten to add, however, that migration responses to long-run changes in climate may differ from responses to weather variability. On the one hand, in situ adaptation measures, e.g., crop switches in agricultural areas20, might temper migration responses to longer-run changes in climate. On the other hand, climate change may induce conditions under which current in situ adaptive measures become insufficient, e.g., if water used for irrigated agriculture becomes limited63. To test our findings against longer-term changes in local climate, we estimate empirical models using temperature and soil moisture values averaged over the 10 years preceding each migration event (Methods). Results hold both across borders and within countries (Supplementary Fig. S11) with demographic and climate zone heterogeneity in migration responses continuing to improve model performance, albeit with the magnitude of weather effects showing somewhat reduced migration sensitivity over the longer run.

A variety of other possible model specifications consistently support the inference that inclusion of demographics is critical for understanding the influence of weather and climate on migration. For instance, lagged effects of weather at origin could theoretically affect mobility46,64,65. We test the effect of adding weather variables lagged by one year and obtain results similar in direction and slightly smaller in magnitude to contemporary weather. While adding lagged effects does not increase out-of-sample performance for within-country migration, age and education heterogeneity still substantially improves performance for both models including lags (Supplementary Fig. S12). We also test the effect of adding destination weather variables and find that it does not improve performance for the within-country model. For cross-border migration, however, added destination weather increases performance by 0.5 percentage points, and allowing the effect of destination weather to differ by age and education again improves performance, in this case by 1.2 percentage points relative to omitting destination weather (Supplementary Fig. S13). Heat in destination countries decreases migration for young, people with lower education levels and has a similar and opposite effect on older people with higher education levels. Increased migration following heat at destination is most pronounced in temperate climates, and least so in dry-hot zones. Conversely, high moisture in destination countries increases migration of adults with higher education levels, with effects largest in tropical climates. The effect of origin weather remains essentially unchanged by the addition of destination effects. These results suggest that young people with lower education levels may not be able to leave hot and dry conditions due to resource constraints exacerbated by heat at origin. As a result, including destination effects amplifies projected effects of climate change on future cross-border migration. We note that such changes add 66 more parameters for the cross-border migration model and, thus, raise issues regarding trade-offs between model performance and interpretability.

Further analyses including individual and household-level characteristics constitute important avenues for future research. For instance, household structure, an important factor for migration decisions, may play a role in the weather-migration relationship. We test the effect of having children at time of migration on this relationship for cross-border migration (Supplementary Fig. S14), though with the caveat that the IPUMS dataset does not provide information on whether said children migrated along with the individual surveyed. We find that including parental status of migrants into our model accounting for demographic and baseline climate heterogeneity increases the predictive performance by 0.2 percentage points. Warming and drying generally reduces migration rates of people without children, whereas effects on parents are weaker and of opposite direction. This provides additional empirical evidence supporting our conclusion that migrant characteristics substantially affect migration responses to weather shocks. In contrast, the sex of a migrant is not found to help predict migration responses to weather in this analysis. We suspect that cultural differences in gendered patterns of migration, including related to gender-specific labor and marriage migration, are likely to affect responses to weather41, yet in ways that we are not able to account for with the data at hand.

Our dual analysis of weather-related moves within and between countries highlights the importance of considering demographic characteristics at multiple migration scales. Beyond the within and between countries dichotomy, we note that migration responses to weather may well differ between and within small versus large countries in a manner not captured by our foregoing analysis. To examine whether the scale of aggregation has an effect, we allow the weather-climate relationship to additionally vary as a function of the size of the origin country or province (Supplementary Fig. S15). We find that allowing for heterogeneity in the weather-migration effect with respect to surface area does not increase model predictive performance out of sample for within-country migration. Across borders, performance increases by just 0.0002 percentage points, yielding small changes in the effect of temperature and negligible changes for soil moisture. Using population size instead of surface area yields similar results. These results suggest that the the scale of aggregation does not modulate the importance of demographic heterogeneity in the weather-migration relationship.

Our findings help bring together the contrasted estimates of weather effects on migration documented in the literature32. Evaluation of model performance out-of-sample makes clear that demographic information on would-be migrants is necessary for a robust assessment of migration responses to weather. Although we are able to reproduce previous studies that do not account for demographic heterogeneity, cross-validation of these approaches indicates little model performance. This suggests that the diversity of documented responses might result from some combination of variation across settings and samples, but also from noise in demographic-blind analyses even if results are statistically significant.

The results presented here also complement prior evidence on differentiated mobility responses to climate variability as a function of demographics, which has to date mostly been limited to within-country migration. We highlight six studies, beginning with two for which there is some disagreement with our findings. Thiede et al.36 use a subset of the same migration data used in our study to analyze within-country migration responses to climate variability in South America. They find that high precipitation levels decrease migration for young individuals and high temperatures increase migration of women and individuals with lower education levels, in line with an explanation of weather as a push factor and with our results in the dry-cold zone, but in contradiction to our results for the other South American climate zones, namely tropical, dry hot, and temperate. In a more recent study, Gray and Thiede39 find, using a different migration data source, that temperature anomalies increase temporary moves within countries of those with higher education levels, whereas precipitation anomalies increase moves of those with lower education levels. Our results indicate that further subdivision of responses according to climate zone is useful and that, in particular, temperature effects arise for migration within countries in tropical areas, whereas hydrological effects arise for within-country moves in dry-hot areas.

With regard to demographic studies that are more in keeping with our results, Helbling and Meierrieks28 find that temperature and precipitation changes affect emigration to OECD countries only for low-skilled individuals, consistent with our finding that weather effects on cross-border migration are generally weaker for older individuals and those with higher education levels. Bohra-Misra et al.37 find that younger males and individuals with higher education levels are more likely to migrate following high temperatures within the Philippines. Ignoring the sex-based distinction, these results are consistent with our findings for the tropical climate zone and the inference that weather acts as a resource constraint for those with lower education. Similarly, Thiede et al.38 find that women and individuals with lower education levels who were exposed to high temperatures during early childhood in Eastern and Southern Africa are less likely to migrate internally later in life. This accords with our findings of contemporary effects of heat on within-country migration of individuals with lower education levels in those climate zones that are associated with Eastern and Southern Africa, namely dry hot, temperate and tropical. Finally, Hoffmann et al.29 use the same within-country migration data as our analysis to show that middle-age groups are more likely to migrate in response to drought in less-developed countries, in line with our results for the dry-hot zone. Taken together, we infer that the differential agreement between our results and country-based or regional analyses reflects, at least in part, heterogeneity within our climate-zone based analysis. Overall, if models of weather effects on migration are to be used for making predictions, we suggest that they should, in addition to statistical significance, display positive out-of-sample performance.

To project migration patterns under future climate change, taking demographic heterogeneity into account matters greatly. Climate change effects on overall cross-border migration between the end of the century and today are found to obscure substantial variation across age and education, with a range of effects increasing from [ − 5%; 1%] to [ − 31%; + 26%] when accounting for demographic heterogeneity. This result suggests that climate change effects on mobility are about who moves, more than about how many people move. From a methodological standpoint, this finding also highlights the importance of including demographics in structural models of migration responses to future climate change66, which have so far explored the role of either education67,68 or income19 in shaping this relationship.

Beyond demographic heterogeneity, our projection results on overall cross-border migration suggest an important takeaway. Contradicting claims of mass migration across borders following future climate change5, total cross-border migration rates are projected to change little, and, if anything, to decrease. While some in destination countries concerned with increases in climate-induced immigration might initially consider these findings good news, concerns about global human welfare suggest another conclusion. Collectively, our results indicate that many among those most likely to suffer from climate change impacts will not be able to get out of harm’s way. This reduced access to migration as an adaptation strategy is itself a consequence of climate change, thereby afflicting a “double penalty" on those most vulnerable. Our findings indicate a need for policy responses that squarely address the demographic complexity of mobility responses to climate.

Methods

Data

Migration data

We use the IPUMS International dataset, developed and maintained by the University of Minnesota, which consists of census data collected every 5–10 years and harmonized across over 100 countries42. As typical in census exercises, data is collected on a subset of the population – generally, around 10%—that is meant to be representative of the overall population. For each observation, a weight is given by the census institution that illustrates how many actual people this person represents. Note that this dataset does not capture short-term moves, hence we focus on long-term migration patterns. The main benefits of this dataset for our purpose are twofold. First, it provides information on both cross-border and within-country migration. Second, it provides information on demographic characteristics of individuals who have migrated in terms of age, sex, and education. A discussion of its limitations is presented in the Supplementary Discussion. Because mobility patterns vary in nature based on whether the move takes place within a country or across borders, and because the information available for cross-border moves involves a different structure from the one documenting within-country moves (see description below), we treat the two subdatasets separately.

Cross-border migration

In this part of the dataset, information is gathered at the country level, by the country of destination. We observe the year of migration (1988−2019), as well as the country of residence at time of census (23 countries represented) and the country of birth of the person surveyed (168 countries represented). We assume that a migrant’s country of birth is the country she came from. Cross-border outmigration rates averaged over the period of observations in each country for which weather data is available are shown in Fig. 1a. Average cross-border immigration rates in each destination country for which data is available are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Within-country migration

In this part of the dataset, information is gathered at the level of subnational administrative units (adm1) by the country where the migration is taking place. Information necessary to document within-country migration is available for 71 countries, covering the period 1989−2019. We observe the current location, as well as the prior location defined as location either 1, 5, 10 years ago, or at time of previous census, depending on the country. We use the census data itself to calculate subnational population size, the denominator of our dependent variable. In order to not loose too many observations, we assume that the origin population size at time of migration is the same as its size at time of the last census prior to migration. Finally, as this part of the dataset is less robust than the cross-border migration section, we winsorize the within-country bilateral migration rates to their 0.5-99.5 percentiles. Within-country outmigration rates averaged over the period of observations in each subnational location for which weather data is available are shown in Fig. 1b. We note that migration rates are higher within countries than across borders.

Demographic profiles of migrants

For both within-country and cross-border migration, we calculate migration rates per demographic group for each location and time. Demographics are coded as follows: four categories for education (primary not completed, primary completed, secondary completed, higher education), four categories for age (under 15, 15−30 years old, 30−45, above 45), and two categories for sex (male, female). As we need information on the age, sex, and education of migrants at time of migration, we assume that a migrant’s education at time of migration is the same as her education at time of census. This is a simplifying assumption likely to be false in some cases; yet for the few observations for which a cause of migration is stated, education only represents 6% of cases. We ensure the absence of unrealistic education by forcing lower than secondary education for individuals younger than 15 at time of migration. The distribution of within-country and cross-border migrants over demographic category (education, age, sex) is displayed in Fig. 1c. Cross-border migrants, on average, have higher education levels and are more likely to be of working age than within-country migrants.

In a robustness check, we test the effect of having children at time of migration on the weather-migration relationship (Supplementary Fig. S14). For this additional analysis, the panel unit of analysis is defined not as a function of age, education, and sex, but instead as a function of age, education, and whether the individual had one or more children at time of migration. The latter characteristic is derived from the IPUMS variables giving the age of eldest own child in the household, as well as the year or period of migration.

Population

Our dependent variable is the logged transformation of the outmigration rate, defined as the ratio of number of migrants to population at origin. For cross-border migration, we use data on national level population size. We use the UN World Population Prospects, which provides yearly country-level population for the period 1950−2100. Its historical portion stems largely from census data, and therefore is highly correlated with IPUMS population estimates for available years. Its projection portion is not used here. For within-country migration, we use the census data itself (see subsection “Within-country migration").

Local temperature data

The Climate Prediction Center compiles and interpolates station measures to produce a gridded daily maximum surface air temperature product with 0. 5∘ by 0. 5∘ resolution from 1979-present43,44. Following51, we use daily maximum rather than mean temperature to better capture human experience of extreme heat stress.

Local soil moisture data

The European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative Plus Soil Moisture Project v06.1 dataset compiles active and passive satellite measures of surface soil moisture down to a depth of 5 cm at daily 0.25∘ × 0.25∘ resolution69,70. Satellite-based measures of surface soil moisture provide a good measure of water availability for plant uptake. See ref. 71 for a detailed discussion, and51,72 for empirical applications to agricultural productivity, a factor relevant to migration. Soil moisture is measured volumetrically, as the volume of water contained within a given volume of soil (i.e., \(\frac{{m}^{3}}{{m}^{3}}\)).

Weighting weather data with population density over the year

For the cross-border migration analysis, we need weather data at the year-by-country level. To that aim, we spatially average the polynomial expansions of daily temperature and soil moisture data over the year across each country, weighting by population density. For the within-country migration analysis, we need weather data at the year-by-subnational unit level. Similarly, we average the polynomial expansions of daily temperature and soil moisture data over the year across each subnational unit. For illustrative purposes, the daily maximum temperature per subnational location for which within-country migration data is available, averaged over the period of observations, is displayed in Supplementary Fig. S3a. A similar representation for soil moisture is displayed in Supplementary Fig. S3b.

Including uncertainty on migration timing in weather data

While the cross-border migration data provides information on the year of migration, the within-country migration data only provides a range of years (see subsection “Within-country migration"). Specifically, 86% of corridor × demographics observations use a specific year, 6% use 1 year periods, 7% use 5 year periods, and 0.5% use 6–10-year periods. In our analysis of within-country movements we use weather levels averaged over the time period corresponding to each census sampling period in order to account for uncertainty in the timing of the migration event. As a robustness check, we use non-averaged weather levels of the earliest possible year of said time period and find similar results for both out-of-sample evaluation and response curves, as makes sense given that observations harboring uncertain migration timing make up less than 8% of the data.

Climate zones

We also explore heterogeneous weather effects on migration across climate zones at origin because the effects of weather variability on mobility are likely to differ depending on the baseline climate. Specifically, we use the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, which identifies five main climate groups and 30 sub-groups52. Here, we consider the five main groups (tropical, dry, temperate, continental, polar), and separate the dry group into two (dry-hot, dry-cold) to better capture effects of temperature and moisture. To map climate zones to the level of our data, we use recent 1 km resolution maps of the Köppen-Geiger climate zones73, and calculate the main climate zone per subnational location or country as the zone associated with the greatest number of people, as computed according to population-weighted grid cells. A geographic representation of the six zones at locations for which migration and weather data is available is given in Supplementary Fig. S3c. We do not present the polar zone in our results because it only accounts for 1% of our observations.

Simulations of temperature and soil moisture under climate change

To project local temperature and soil moisture values under future climate change, we use data from the 6th phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6)74. We extract gridded daily temperature and soil moisture. Temperature is the daily maximum two-meter air temperature ("tmax”) and surface soil moisture is that in the top 10 cm of soil ("mrsos”), which generally accords with satellite measures used in empirical analyses71. We process these to the country-by-year level by first taking polynomial expansions of the daily data and then averaging over the year and national boundaries, weighting by population. We use values from the SSP5-8.5 scenario over two periods: 2015–2035 and 2080–2100. To get a single central estimate we take the median of the processed output over 15 models. The models are ACCESS-ESM1-5, BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, CMCC-ESM2, EC-Earth3, GFDL-CM4, INM-CM4-8, INM-CM5-0, IPSL-CM6A-LR, KACE-1-0-G, MIROC6, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, MRI-ESM2-0, and NorESM2-LM.

To estimate local temperature and soil moisture changes for SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0, we apply a pattern scaling approach75. We calculate the SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0 change values by scaling the local changes in temperature and soil moisture from the SSP5-8.5 scenario by the fraction of global mean surface temperature change between the cooler scenario and the warmer scenario. Scaling is performed separately for the linear, quadratic, and cubic weather terms at each location to allow for differential rates of change between average temperature and temperature extremes:

Here s is the scenario of interest, so is the benchmark scenario, i is the location, and \(\bar{T}\) is global mean surface temperature. Scaling for soil moisture is analogous.

We rescale the SSP5-8.5 data rather than using data from SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0 directly because SSP5-8.5 was the scenario for which the largest number of models had available daily temperature and soil moisture projections at the time of analysis, and because the sets of models offering projections differ substantially across scenarios. Using and scaling the SSP5-8.5 projections allows us to incorporate the greatest number of CMIP6 models – 15 – and maintain a constant set of CMIP6 models across various warming levels associated with different SSP scenarios. A large model ensemble enables us to average over and attenuate noise from substantial differences in simulated values across climate models. In addition, maintaining a constant set of climate models across scenarios ensures that differences in results across scenarios are attributable to differences in climatic changes, not to the climate models used. An illustration of how weather variables evolve under medium climate change as represented by the increase in global mean temperature between periods 2015–2035 and 2080–2100 can be found in Supplementary Fig. S16.

Looking at the linear terms, we find that the CMIP6 models yield a local warming that is lower than the global average for 36 countries and higher for 125 countries, which is in line with the fact that land warms more quickly than oceans. We also find that increased global mean temperature leads to dryer conditions in 122 countries, and to wetter conditions in 39 countries, although the cross-model range includes 0 for most countries.

Estimating the effects of weather on migration

Empirical model

We identify the effect of weather on migration of various demographic groups. The panel unit of analysis is the proportion of people from a specific demographic group (defined as a function of age, education, and sex) that leave their origin to go to a given destination. We compare this unit of observation to itself over time as a non-linear function of temperature and soil moisture of that year in the origin location (Eq. (2)). Note that because mobility patterns vary in nature based on whether the move takes place within a country or across borders, we model within-country migration separately from cross-border migration.

The migration rate is computed as the ratio of the number of people of demographic characteristics Z moving from origin o to destination d at time t to total population size in o at t. Following22,76, we use the log transformation of the migration rate as the dependent variable. The coefficients of interest are the β coefficients, which give the effects of temperature T and soil moisture SM levels (in degrees Celsius and cm3 of water per cm3 of soil) in cubic form. The cubic form is chosen as the one giving the highest model performance among a linear, quadratic, cubic, or restricted cubic splines model. Similarly, the temperature and soil-moisture pairing gives the highest performance as compared to models using solely temperature, solely soil moisture, solely precipitation, or temperature and precipitation jointly (Supplementary Fig. S17). Vector Z describes demographic characteristics by grouping three indicator variables for the education, age, and sex of migrants.

Time-invariant fixed effects θod,Z are specified for each triplet of origin, destination, and demographic group that account for, e.g., geographic proximity between origin and destination as well as existing diasporas, reflecting the persistence of migration flows. Location-invariant yearly fixed effects ψt are also included to account for migration rate variations that might occur, for example, in response to a global economic shock. Finally, we include a time trend in migration δot for each origin location to account for factors such as technology developments. The residual ϵod,t,Z captures all remaining drivers varying over time within origin-destination-demographic groupings but uncorrelated with the weather variables. We compute standard errors clustering by origin location. Origin locations are subnational for within-country migration and country for cross-border migration.

Testing for heterogeneity across climate zones

As noted earlier, the effects of weather on mobility are likely to differ depending on the baseline climate. To test this hypothesis, we build off Eq. (2), whose terms are indicated by the (2) below.

The new terms interact weather variables with an indicator for the climate zone K of the origin location (Eq. (3)).

Testing for heterogeneity across demographic characteristics of migrants

Weather might also affect various demographic groups differently, since observed mobility patterns already differ across demographics. To refine our understanding of who is effected by weather, we interact weather variables in turn with age a, education e, sex s, and their combinations (Eq. (4)).

Weather might also affect different demographic groups differently in each climate zone. To test this, we estimate a model building off of models (2)-(4) that additionally interacts weather variables with both demographics and climate zones simultaneously.

Testing for effects of longer-term changes in local climate

As a robustness check we estimate empirical models using temperature and soil moisture values averaged over the 10 years preceding each migration event (Eq. (5)). This approach allows us to examine whether our results, conditioned primarily on single-year weather, alter when examined relative to longer-term changes in local climate. Comparing these effects with effects of shorter-term weather shocks used in our main specifications highlights if and how migration responses change sensitivity over the longer run,

Assessing the predictive ability of our empirical models

Once the experimental design is set by the fixed effects described in the subsection “Empirical model", we keep the same design and use the data after removing fixed effects (i.e., the identifying variation) to conduct cross-validation exercises. This process enables us to assess each migration model’s predictive performance out-of-sample. Out-of-sample performance, rather than statistical significance, is used for model selection. To calculate predictive performance, we use 10-fold cross-validation whereby we split the data randomly into 10 folds and use 9 folds for training and the one remaining fold for validation. Models are trained and predictions made for each of the 10 folds. Performance is calculated on these combined out-of-sample predictions using the coefficient of determination (R2), which can be interpreted as the share of variation in migration explained out-of-sample after corridor-by-demographic intercepts, year intercepts and origin-specific trends have been removed. The model R2 considers both errors related to model bias, which stem from the expected value of the estimated function differing from that of the true function, and errors related to model variance, which stem from the estimated function differing from its expected value77. To address potential concerns of over-fitting to the validation set through model selection, we conduct a placebo test where we shuffle the weather observations and refit the model. Consistent with overfitting not being an issue, the shuffled placebo version has no out-of-sample performance across all specifications. To calculate an uncertainty range for the model performance, we use 20 different seeds for splitting the data into 10 folds, and conduct cross-validation for each of the seeds. We present results using the distribution of R2 over the 20 seeds (lower to upper adjacent values). Unless specified otherwise, all hypothesis tests are relative to a null of no effect, and are two-tailed.

To ensure the robustness of our results to the choice of performance metric, we also compute the Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS)78, using the exact same cross-validation procedure (Supplementary Fig. S18). To that aim, we assume a Gaussian distribution of predicted values over the testing sample, and we calculate the CRPS averaged over observations in the testing sample. Note that the CRPS is a measure of the prediction error; a lower CRPS reflects a better performing model. The CRPS gives results that are very similar to those obtained for R2 for both within-country and cross-border migration. For within-country moves, the rankings of model performance based on CRPS and R2 are the same, except that the model including heterogeneity per sex in addition to age and education for each climate zone has a slightly better (lower) CRPS than the model performing best in terms of R2. The Spearman’s rank correlation between R2 and CRPS is -0.98 (note that the negative value results from the opposite ranking order between the two metrics). For cross-border migration, model ranking remains similar across R2 and CRPS performance metrics, except that the model allowing differences per climate zone interacted with age and education gives the best (lowest) CRPS score, on average, though with a much more variable score. The Spearman’s rank correlation between R2 and CRPS is -0.39 if including this model, and -.81 if not. Given this model’s low and uncertain predictive performance as measured by the R2, and its uncertain performance as expressed by the CRPS, we instead choose the model allowing for differences per age, education, and climate zone as our primary specification because it performs best in terms of R2 and second best in terms of CRPS. Overall, we use the best model according to R2, because of its simplicity of interpretation (variance explained) and common use in the literature, and note that findings are generally consistent with model selection based on CRPS.

We perform cross-validation for our main line of results by splitting data into random folds in order to evaluate the ability of models to explain historical migration. To more fully characterize how our best performing models can be used for prediction in policy-relevant contexts, we conduct additional tests of model ability to temporally extrapolate by splitting the data into folds by year, as opposed to the random splits as done in the main analysis. This approach forces predictions to be made and evaluated for years not represented in the training data and is of specific use for evaluating model use in future climate change projections.

For both within-country and cross-border migration, our best performing models maintain positive performance over time, though their performance is not significantly different from zero (Supplementary Fig. S8). To account for the additional challenge of extrapolating over time, we try a simpler model for cross-border migration, whereby we restrict the dimensions of heterogeneity considered to age and education, and use a linear rather than cubic functional form for temperature, as temperature responses are found to be approximately linear (Fig. 2b). We find that this simpler model generalizes better to held-out observations over time (out-of-sample R2 = 0.0010 [0.0005;0.0015]) and thus use it for climate change projections. A representation of its response curves is given in Supplementary Fig. S9.

Projections in a future with increasing climate change

Once the best performing model is selected, we use it as basis for a projection exercise of migration patterns with increasing climate change over the 21st century. As a straightforward application, we project this model assuming that climate is the only changing factor while other drivers of migration do not otherwise change. To project local temperature and soil moisture values under future climate change, we use data from the 6th phase of the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project (CMIP6). We extract from it polynomial expansions of local temperature and soil moisture (see Data). We then compute the change in migration rates resulting from changes in local weather variables between two periods, 2015–2035 and 2080–2100, consistent with a medium climate change scenario (SSP2-4.5) and a pessimistic one (SSP3-7.0), in the countries and demographic groups present in the estimation sample.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed for this study are available in the Harvard Dataverse database under accession code https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FKEPAN79.

Code availability

The data handling and analysis were conducted in Stata (version 18.5, packages estout, ftools, distinct, winsor2, palettes, colrspace, spmap, reghdfe, heatplot, egenmore, mylabels, outreg2, shp2dta) and R (version 4.2.3, packages data.table, Hmisc, foreach, doParallel, parallel, ncdf4, raster, maps, maptools, sp, sf, rgeos, rgdal, ggplot2). Most figures except maps were produced with Stata, while maps-based figures were generated with QGIS (version 3.34.15). The complete codes used to generate and visualize the results of this study are available in the Harvard Dataverse database under accession code https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FKEPAN79.

References

Nanditha, J. S. et al. The Pakistan flood of August 2022: Causes and implications. Earth’s Future 11, e2022EF003230 (2023).

Burke, S., Saccoccia, L., Schmeier, S., Faizee, M. & Chertock, M. How Floods in Pakistan Threaten Global Security. https://www.wri.org/insights/pakistan-floods-threaten-global-security (2023).

United States Department of Homeland Security Yearbook of immigration statistics 2019. Tech. Rep., U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics (2020).

Lustgarten, A. The Great Climate Migration Has Begun. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/23/magazine/climate-migration.html (2020).

Boas, I. et al. Climate migration myths. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 901–903 (2019).

The White House. United States White House Report On The Impact Of Climate Change On Migration. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Report-on-the-Impact-of-Climate-Change-on-Migration.pdf (2021).

Podesta, J. The Climate Crisis, Migration, And Refugees. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-climate-crisis-migration-and-refugees/ (2019).

Nishimura, L. The Slow Onset Effects Of Climate Change And Human Rights Protection For Cross-border Migrants. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1480422?ln=en (2018).

de Haas, H. A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. Comp. Migr. Stud. 9, 8 (2021).

Schewel, K. Understanding immobility: moving beyond the mobility bias in migration studies. Int. Migr. Rev. 54, 328–355 (2020).

Zickgraf, C. Theorizing (im)mobility in the face of environmental change. Reg. Environ. Change 21, 1–11 (2021).

Adams, H. Why populations persist: mobility, place attachment and climate change. Popul. Environ. 37, 429–448 (2016).

Carling, J. Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: theoretical reflections and cape verdean experiences. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 28, 5−42 (2002).

de Haas, H. et al. International migration: trends, determinants, and policy effects. Popul. Dev. Rev. 45, 885–922 (2019).

Rigaud, K. K. et al. Groundswell: Preparing For Internal Climate Migration. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/2be91c76-d023-5809-9c94-d41b71c25635 (2018–2021).

Black, R., Bennett, S. R. G., Thomas, S. M. & Beddington, J. R. Migration as adaptation. Nature 478, 447–449 (2011).

McLeman, R. Thresholds in climate migration. Popul. Environ. 39, 319–338 (2018).

Bekaert, E., Ruyssen, I. & Salomone, S. Domestic and international migration intentions in response to environmental stress: a global cross-country analysis. J. Demographic Econ. 87, 3 (2021).

Benveniste, H., Oppenheimer, M. & Fleurbaey, M. Climate change increases resource-constrained international immobility. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 634–641 (2022).

Choquette-Levy, N., Wildemeersch, M., Oppenheimer, M. & Levin, S. A. Risk transfer policies and climate-induced immobility among smallholder farmers. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 1046–1054 (2021).

Adger, W. N. et al. Focus on environmental risks and migration: causes and consequences. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 060201 (2015).

Cai, R., Feng, S., Oppenheimer, M. & Pytlikova, M. Climate variability and international migration: the importance of the agricultural linkage. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 79, 135–151 (2016).

Riosmena, F., Nawrotzki, R. & Hunter, L. Climate migration at the height and end of the great mexican emigration era. Popul. Dev. Rev. 44, 455 (2018).

Cattaneo, C. & Peri, G. The migration response to increasing temperatures. J. Dev. Econ. 122, 127–146 (2016).

Peri, G. & Sasahara, A. The Impact Of Global Warming On Rural-urban Migrations: Evidence From Global Big Data. http://www.nber.org/papers/w25728 (2019).

Nawrotzki, R. J. & DeWaard, J. Putting trapped populations into place: climate change and inter-district migration flows in zambia. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 533−546 (2018).

Grecequet, M., DeWaard, J., Hellmann, J. J. & Abel, G. J. Climate vulnerability and human migration in global perspective. Sustainability 9, 720 (2017).

Helbling, M. & Meierrieks, D. How climate change leads to emigration: conditional and long-run effects. Rev. Dev. Econ. 25, 2323–2349 (2021).

Hoffmann, R., Abel, G., Malpede, M., Muttarak, R. & Percoco, M. Drought and aridity influence internal migration worldwide. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 1245–1253 (2024).

Cattaneo, C. et al. Human migration in the era of climate change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 13, 189–206 (2019).

Millock, K. Migration and environment. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 7, 35–60 (2015).

Hoffmann, R., Dimitrova, A., Muttarak, R., Cuaresma, J. C. & Peisker, J. A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 904–912 (2020).

Beyer, R. M., Schewe, J. & Abel, G. J. Modeling climate migration: dead ends and new avenues. Front. Clim. 5, 1212649 (2023).

Mastrorillo, M. et al. The influence of climate variability on internal migration flows in south africa. Glob. Environ. Change 39, 155–169 (2016).

Mueller, V., Gray, C. & Kosec, K. Heat stress increases long-term human migration in rural pakistan. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 182–185 (2014).

Thiede, B. C., Gray, C. & Mueller, V. Climate variability and inter-provincial migration in south america. Glob. Environ. Change 41, 228–240 (2016).

Bohra-Mishra, P., Oppenheimer, M., Cai, R., Feng, S. & Licker, R. Climate variability and migration in the philippines. Popul. Environ. 38, 286–308 (2017).

Thiede, B. C., Randell, H. & Gray, C. The childhood origins of climate-induced mobility and immobility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 48, 767−793 (2022).

Gray, C. & Thiede, B. C. Temperature anomalies undermine the health of reproductive-age women in low-and middle-income countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2311567121 (2024).

Massey, D. S. et al. Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 19, 431–466 (1993).

Hunter, L. M., Luna, J. K. & Norton, R. M. The environmental dimensions of migration. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 377 (2015).

Ruggles, S. et al. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version D020.V7.3 https://www.ipums.org/projects/ipums-international/d020.v7.3 (2020).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Physical Sciences Laboratory CPC Global Unified Temperature. https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globaltemp.html (2025).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Physical Sciences Laboratory CPC Global Unified Gauge-Based Analysis of Daily Precipitation. https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globalprecip.html (2025).

Barrios, S., Bertinelli, L. & Strobl, E. Climatic change and rural–urban migration: the case of sub-saharan africa. J. Urban Econ. 60, 357–371 (2006).

Coniglio, N. D. & Pesce, G. Climate variability and international migration: an empirical analysis. Environ. Dev. Econ. 20, 434–468 (2015).

Ghimire, R., Ferreira, S. & Dorfman, J. H. Flood-induced displacement and civil conflict. World Dev. 66, 614–628 (2015).

Marchiori, L., Maystadt, J.-F. & Schumacher, I. The impact of weather anomalies on migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 63, 355—374 (2012).

Maurel, M. & Tuccio, M. Climate instability, urbanisation and international migration. J. Dev. Stud. 52, 735–752 (2016).

Missirian, A. & Schlenker, W. Asylum applications respond to temperature fluctuations. Science 358, 1610–1614 (2017).

Proctor, J., Rigden, A., Chan, D. & Huybers, P. More accurate specification of water supply shows its importance for global crop production. Nat. Food 3, 753–763 (2022).

Köppen, W. Die wärmezonen der erde, nach der dauer der heissen, gemässigten und kalten zeit und nach der wirkung der wärme auf die organische welt betrachtet. Meteorol. Z. 1, 215–226 (1884).

Carleton, T. et al. Valuing the global mortality consequences of climate change accounting for adaptation costs and benefits. Q. J. Econ. 137, 2037–2105 (2022).

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235–239 (2015).

Hultgren, A. et al. Impacts of climate change on global agriculture accounting for adaptation. Nature 642, 644–652 (2025).

Molina, M. & Garip, F. Machine learning for sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 45, 27–45 (2019).

Hofman, J. M., Sharma, A. & Watts, D. J. Prediction and explanation in social systems. Science 355, 486–488 (2017).

Gelman, A. & Loken, E. The statistical crisis in science. Am. Sci. 102, 460–465 (2014).

Kuchibhotla, A. K., Kolassa, J. E. & Kuffner, T. A. Post-selection inference. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 9, 505–527 (2022).

Breiman, L. Statistical modeling: the two cultures (with comments and a rejoinder by the author). Stat. Sci. 16, 199–231 (2001).

Ronco, M. et al. Exploring interactions between socioeconomic context and natural hazards on human population displacement. Nat. Commun. 14, 8004 (2023).

Government of Kenya. Kenya Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (pdna) 2008-2011 Drought. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/kenya-post-disaster-needs-assessment (2012).

Elliott, J. et al. Constraints and potentials of future irrigation water availability on agricultural production under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3239–3244 (2014).

Black, R. et al. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Change 21S, S3–S11 (2011).

Molina, M., Chau, N., Rodewald, A. D. & Garip, F. How to model the weather-migration link: a machine-learning approach to variable selection in the mexico-u.s. context. J. Ethn. Migr.Stud. 49, 465-491 (2022).

Cruz, J.-L. & Rossi-Hansberg, E. The economic geography of global warming. Rev. Econ. Stud. 91, 899–939 (2023).

Burzyński, M., Deuster, C., Docquier, F. & De Melo, J. Climate change, inequality, and human migration. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 20, 1145–1197 (2022).

Burzyński, M., Docquier, F. & Scheewel, H. The geography of climate migration. J. Demographic Econ. 87, 345–381 (2021).

Dorigo, W. et al. Esa cci soil moisture for improved earth system understanding: state-of-the art and future directions. Remote Sens. Environ. 203, 185–215 (2017).

Gruber, A., Scanlon, T., Schalie, R. V. D., Wagner, W. & Dorigo, W. Evolution of the esa cci soil moisture climate data records and their underlying merging methodology. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 717–739 (2019).

Feldman, A. F. et al. Remotely sensed soil moisture can capture dynamics relevant to plant water uptake. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR033814 (2023).

Rigden, A. J., Mueller, N. D., Holbrook, N. M., Pillai, N. & Huybers, P. Combined influence of soil moisture and atmospheric evaporative demand is important for accurately predicting us maize yields. Nat. Food 1, 127–133 (2020).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future köppen-geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 5, 1–12 (2018).

Tebaldi, C. et al. Climate model projections from the scenario model intercomparison project (scenariomip) of cmip6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 253–293 (2021).

Mitchell, T. D. Pattern scaling: an examination of the accuracy of the technique for describing future climates. Clim. Change 60, 217–242 (2003).

Cottier, F. & Salehyan, I. Climate variability and irregular migration to the european union. Glob. Environ. Change 69, 102275 (2021).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning, 2nd edn, Vol. 745 (Springer New York Inc., 2001).

Gneiting, T. & Raftery, A. E. Strictly proper scoring rules, prediction, and estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 102, 359–378 (2007).

Benveniste, H., Huybers, P. & Proctor, J. Replication Data For: Global Climate Migration Is A Story Of Who And Not Just How Many. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FKEPAN (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Joseph Aldy, Tom Bearpark, Adrien Bilal, Tamma Carleton, and Michael Oppenheimer for useful comments. H.B. was supported by the French Environmental Fellowship Fund at the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability’s Research Cluster on climate adaptation in South Asia at Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.B., P.H., and J.P. conceived the study. J.P. processed the temperature and soil moisture data. H.B. processed the migration and population data. H.B. performed the empirical analysis and projections. All authors interpreted results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benveniste, H., Huybers, P. & Proctor, J. Global climate migration is a story of who and not just how many. Nat Commun 16, 7752 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62969-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62969-3

This article is cited by

-

Broadening climate migration research across impacts, adaptation and mitigation

Nature Climate Change (2026)

-

Who moves under climate stress

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)