Abstract

The frustrated insulating magnet can stabilize a spiral spin liquid, arising from cooperative fluctuations among a subextensively degenerate manifold of spiral configurations, with ground-state wave vectors forming a continuous contour or surface in reciprocal space. The atomic-mixing-free honeycomb antiferromagnet GdZnPO has recently emerged as a promising spiral spin-liquid candidate, hosting nontrivial topological excitations. Despite growing interest, the transport and topological properties of spiral spin liquids remain largely unexplored experimentally. Here, we report transport measurements on high-quality, electrically insulating GdZnPO single crystals. We observe a giant low-temperature magnetic thermal conductivity down to ~ 50 mK, described by \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,{\kappa }_{0}+{\kappa }_{1}T\), where both κ0 and κ1 are positive constants associated with excitations along and off the spiral contour in reciprocal space, respectively. This behavior parallels the magnetic specific heat, underscoring the presence of mobile low-energy excitations intrinsic to the putative spiral spin liquid. Furthermore, the observed positive thermal Hall effect confirms the topological nature of at least some of these excitations. Our findings provide key insights into the itinerant and topological properties of low-lying spin excitations in the spiral spin-liquid candidate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In strongly correlated magnets, frustration can give rise to exotic phases such as spin liquids, characterized by fractionalized excitations, long-range entanglements, and topological order1,2. These phases hold potential for applications in topological quantum computation3, spintronics devices4,5, and understanding high-temperature superconductivity6. Notably, some frustrated magnets with large spin quantum numbers (S) can stabilize spiral spin liquids (SSLs). The SSL emerges from cooperative fluctuations among subextensively degenerate spiral configurations, with ground-state wave vectors (QG) forming a continuous contour or surface in reciprocal space for two- (2D) or three-dimensional (3D) systems7,8. For instance, the SSL is predicted to stabilize in the easy-plane (D ≥ 0) frustrated honeycomb-lattice model \({{\mathcal{H}}}={J}_{1}{\sum }_{\langle j0,j1\rangle }{{{\bf{S}}}}_{j0}\cdot {{{\bf{S}}}}_{j1}+{J}_{2}{\sum }_{\langle \langle j0,j2\rangle \rangle }{{{\bf{S}}}}_{j0}\cdot {{{\bf{S}}}}_{j2}+D{\sum }_{j0}{({S}_{j0}^{z})}^{2}-{\mu }_{0}Hg{\mu }_{{{\rm{B}}}}{\sum }_{j0}{S}_{j0}^{z}\), where J1 and J2 are the first- and second-nearest-neighbor Heisenberg couplings, H is the applied magnetic field along the z axis, and g is the g factor9,10,11,12,13,14. This SSL is predicted to remain stable down to very low temperatures14, with QG forming a continuous contour around the Γ{0, 0} point for 1/2 > ∣J2/J1∣ > 1/6, or around the K{1/3, 1/3} point for ∣J2/J1∣ > 1/2.

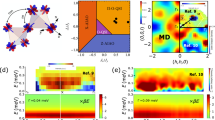

Recently, the honeycomb antiferromagnet GdZnPO emerged as a promising candidate for realizing the above prototypical model experimentally (see Fig. 1), with S = 7/2, J1 ~ −0.39 K, J2 ~ 0.57 K, D ~ 0.30 K, and g ~ 215. With J2/J1 ~ −1.5, QG is expected to form a degenerate spiral contour around the K point below the crossover temperature T* ~ 2 K, accompanied by low-energy topological excitations on the sublattices15. These excitations, including spin and momentum vortices, offer potential for applications in antiferromagnetic spintronics without magnetic field leakage4,5, topologically protected memory and logic operations16, fracton gauge theory17,18,19, and beyond. Moreover, the spiral contour’s approximate U(1) symmetry in momentum space15,20 may enrich symmetry-breaking states, such as unidirectional spin-density waves21, making SSLs promising platforms for exploring related phenomena like unidirectional pair-density waves. However, the transport and topological properties of SSLs remain largely unexplored experimentally.

a Crystal structure showing magnetic GdO layers separated by nonmagnetic ZnP layers, with an average interlayer distance dinter = c/3 (~10.2 Å). The first- and second-nearest-neighbor exchanges J1 and J2 are indicated. Thin lines denote the unit cell. b Honeycomb lattice of Gd3+ ions. Inset: coordinate system for spin components and thermal transport. c Magnetic specific heat Cm of sample SH1 in selected magnetic fields (μ0H) applied along the c axis. Colored lines are linear fits Cm ~ C0+ C1T below the temperature where Cm begins to exhibit linear behavior: below 0.7 K for μ0H < 11 T, below 0.15 K at μ0H = 11 T, below 0.2 K at μ0H = 11.5 T, and below 0.12 K at μ0H = 12 T. The fitted parameters C0 and C1 are shown in Fig. 3f. Crossover temperature T* is marked, and error bars, 1σ s.e.

The specific heat (Cm) of the generic 2D SSL is unusually large, following Cm ~ C0+ C1T at low temperatures, within the spherical approximation7,8. In the SSL, QG fluctuates along the continuous contour in reciprocal space, in sharp contrast to conventional magnetic states where QG adopts discrete values. Analogous to an ideal gas, this implies the presence of low-temperature spin degrees of freedom along the spiral contour, giving rise to a finite residual specific heat C0. Therefore, C0 arises from zero-energy excitations along the degenerate continuous contour in the classical limit (S → ∞), while the C1T term reflects low-energy excitations off the contour. To our knowledge, this low-T behavior of Cm ~ C0+ C1T had not been experimentally observed in any other compounds until our previous report on the SSL candidate GdZnPO15. In GdZnPO, measurements reveal C0 = 0.9−1.4 JK−1/mol and C1 = 1.6−3.4 JK−2/mol below the crossover field μ0Hc ~ 12 T, which separates the putative SSL and the polarized phase and is analytically given by μ0Hc = \(S[2D+3{J}_{1}+9{J}_{2}+{J}_{1}^{2}/(4{J}_{2})]/(g{\mu }_{{{\rm{B}}}})\) in the classical limit (see Fig. 1c). These results support the stability of the honeycomb SSL down to at least ~ 50 mK. For H ≥ Hc, the GdZnPO spin system becomes nearly fully polarized in a nondegenerate ferromagnetic phase. The field-induced transition from this ferromagnetic state (H ≥ Hc) to the degenerate SSL (H < Hc) results in a significant entropy increase, decalescence, and a giant magnetocaloric effect–exceeding other known materials–underscoring GdZnPO’s potential for magnetic cooling applications down to ~ 36 mK22.

Despite extensive efforts23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, magnetic insulators with large thermal conductivity in the low-temperature limit remain exceptionally rare. GdZnPO single crystals are transparent insulators with no evident atomic-mixing disorder15,46,47. At low temperatures, the observed giant magnetic specific heat (Cm)15 reflects a high density of low-energy spin excitations, which can lead to significant magnetic thermal conductivity \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,\frac{{C}_{{{\rm{m}}}}{\lambda }_{{{\rm{m}}}}{v}_{{{\rm{m}}}}}{3{N}_{{{\rm{A}}}}{V}_{0}}\), provided the mean free path (λm) and velocity (vm) remain nonzero. Here, V0 = 67.6 Å3 represents the volume per formula. Consequently, GdZnPO may serve as a rare example of an insulator that supports mobile unconventional spin excitations at low temperatures, offering an excellent platform for investigating the transport and topological properties of a 2D SSL candidate.

In this work, we conducted comprehensive transport measurements on five independent GdZnPO single-crystal samples. The sample with higher crystal quality exhibited reduced electric conductivity but enhanced thermal conductivity, indicating a nonzero intrinsic \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\) in the low-temperature limit. At low temperatures, the behavior \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,{\kappa }_{1}T\) + κ0 is clearly observed in the highest-quality crystals. This behavior aligns well with the giant magnetic specific heat, Cm ~ C1T + C0, suggesting the presence of mobile, high-density spin excitations in GdZnPO. Additionally, a positive thermal Hall effect is observed, supporting the emergence of nonzero Chern numbers. Our findings suggest the itinerant and topological nature of low-lying excitations in the putative SSL, motivating further study.

Results

Toward intrinsic transport properties

Figure 1 a shows the crystal structure of GdZnPO15,46,47. The first-nearest-neighbor coupling, J1 (with ∣Gd-Gd∣1 ~ 3.7 Å), and the second-nearest-neighbor coupling, J2 (with ∣Gd-Gd∣2 = a ~ 3.9 Å), are mediated by Gd-O-Gd exchanges within the magnetic GdO layers. These magnetic layers are well separated by nonmagnetic ZnP layers, with an average interlayer distance of dinter ~ 10.2 Å, indicating negligible interlayer coupling. The magnetic Gd3+ ions form a J1-J2 frustrated quasi-2D honeycomb lattice (Fig. 1b). Because of the zero orbital quantum number (L = 0) and negligible spin-orbit coupling of Gd3+, interaction anisotropy, such as Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya (DM) anisotropy, is expected to be minimal. This is confirmed by the measured g = 2.01(2)15, closely matching the free electron value ( ge = 2.0023). The maximum DM interaction strength is estimated to be about (∣g − ge∣/ge)J2 ~ 1.4%J2 (~ 0.01 K)48 in GdZnPO.

Because thermal conductivity is highly sensitive to crystal quality, we first measured the low-temperature thermal conductivity of four randomly selected crystals (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1−6), followed by Laue x-ray diffraction (XRD) at 300 K and electrical resistivity below 300 K, to identify the intrinsic transport properties of GdZnPO. Fig. 2a shows the zero-field longitudinal thermal conductivity (κxx) data for samples TC1-TC4. The measured κxx/T vs. T curves are broadly similar across all investigated samples. However, sample TC4 exhibits a downturn below ~ 0.3 K, contrasting with the behavior of the other samples. Such low-temperature suppression of κxx /T has also been reported in various magnetic systems, including PbCuTe2O642, YbMgGaO427, Na2Co2TeO625, and Cu(C6H5COO)2⋅3H2O43. This phenomenon has been attributed to spin gap opening, many-body localization, and/or disorder effects that suppress the transport of spin excitations25,27,42,43. Laue XRD measurements were conducted to assess the crystallinity of each sample. Sample TC4 exhibits significantly broader reflections than the other samples, as shown in Fig. 2c and the raw Laue XRD patterns in Supplementary Fig. 3, indicating a smaller average grain size. Crystal grain boundaries and other structural imperfections likely scatter quasi-particles, reducing their mean free path and thereby suppressing the thermal conductivity at low temperatures.

a Zero-field thermal conductivity (κxx) of four samples, plotted as κxx/T vs T, respectively. b Zero-field electrical resistivity (\({\rho }_{xx}^{{{\rm{e}}}}\)). Colored lines show Arrhenius-law fits, \({\rho }_{xx}^{{{\rm{e}}}}\) = \({\rho }_{\infty }^{{{\rm{e}}}}\exp\)(Δe/T), with fitted gap values Δe shown in (c). c Sample dependence of κxx/T at 70 mK, average Laue x-ray diffraction full width at half maximum (Laue FWHM), and Δe. In c, error bars, 1σ s.e.

The electric resistivity (\({\rho }_{xx}^{{{\rm{e}}}}\)) data measured for the four samples are presented in Fig. 2b. As the temperature decreases below 300 K, \({\rho }_{xx}^{{{\rm{e}}}}\) (≥ 300 Ωm) increases, approximately following the Arrhenius law, \({\rho }_{xx}^{{{\rm{e}}}}\) = \({\rho }_{\infty }^{{{\rm{e}}}}\exp\)(Δe /T), where \({\rho }_{\infty }^{{{\rm{e}}}}\) and Δe denote the high-temperature resistivity limit and the thermally activated gap, respectively. Below ~ 90 K (for sample TC4) to 200 K (for sample TC3), the resistances (~ 0.7−1.4 MΩ at 300 K) exceeded the measurement range (≤ 6 MΩ) of the physical property measurement system (PPMS). The gap Δe is roughly proportional to the low-temperature κxx/T, while inversely correlated with the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of Laue XRD reflections (see Fig. 2c). In insulating materials, crystal imperfections can introduce charge carriers and impair electrical insulation44,49.

Consequently, higher-quality GdZnPO crystals with sharper Laue XRD reflections exhibit improved electrical insulation (with larger Δe) and enhanced low-temperature thermal conductivity. A similar trend has also been reported in the electrically insulating magnet 1T-TaS244. These observations firmly establish the intrinsic low-temperature properties of GdZnPO: (1) electrical insulation and (2) the presence of itinerant magnetic excitations. Notably, the high-quality sample TC3 shows a large κxx/T value of ~ 160 mWK−2 m−1 at 70 mK and 0 T (the phonon contribution ≤ 6 mWK−2 m−1 is negligible, see below), exceeding that of most other known electrically insulating magnets.

At low temperatures below 1 K, most of the thermal conductivity data across various measured fields can be well described by κxx ~ κ0 + κ1T + KpT3 (Supplementary Fig. 11). Here, the phonon prefactor Kp is given by \({K}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\, \sim \,\frac{4{\pi }^{4}{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{\lambda }_{{{\rm{p}}}}{v}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}{5Z{V}_{0}{\Theta }_{{{\rm{D}}}}^{3}}\), where vp = \(\frac{{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{\Theta }_{{{\rm{D}}}}}{\hslash }{(\frac{Z{V}_{0}}{6{\pi }^{2}})}^{\frac{1}{3}}\) (~ 2900 m/s) represents the phonon mean velocity, ΘD ~ 117.5 K is the Debye temperature determined from the specific heat of the nonmagnetic reference compound YZnPO (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 16)50,51, Z = 6 is the number of formulas per unit cell, and λp is the phonon mean free path. From the fitted values of Kp = 0.023, 0.052, 0.069, and 0.066 WK−4 m−1, we obtain λp ~ 4.8, 10.9, 14.5, and 13.8 μm for samples TC1-TC4, respectively—much smaller than the corresponding average sample width W = 2\(\sqrt{A/\pi }\) (~ 251, 353, 252, and 258 μm), where A denotes the cross-sectional area. Assuming λp = W, the maximum phonon contribution to κxx/T is calculated as KpT2 ~ 6 mWK−2 m−1 at T = 70 mK for sample TC3.

In practice, fitting low-T thermal conductivity data often yields a λp that is significantly smaller than W33,42,52,53, as summarized in Supplementary Tab. 1. To our knowledge, there is no widely accepted explanation for this discrepancy. A natural speculation is that it arises from phonon scattering at grain boundaries or other imperfections that limit the phonon mean free path, despite the macroscopic sample dimensions. However, other studies—including our previous work on high-quality single crystals of α-CoV2O6 using a similar experimental setup54—have reported a λp comparable to W 55. These suggest that the crystallinity of the randomly selected samples TC1-TC4 may simply have been insufficient. In the next section, we identify a higher-quality GdZnPO crystal, TC5, which exhibits sharp Laue photographs, improved electrical insulation, and significantly enhanced low-temperature thermal conductivity.

The average grain size may be roughly estimated from λp (≥ 4.8 μm), which is usually smaller than W, yet still more than four orders of magnitude larger than the lattice constant a ~ 3.9 Å. Theoretically, finite-size effects in thermodynamic properties become negligible when considering large spin clusters—on the order of 104 × 104 × 104 sites. Therefore, no significant sample dependence is expected for the thermodynamic properties of our GdZnPO crystals. We have measured the low-temperature specific heat on two additional samples (SH1 and SH2) with different crystallinity qualities (Supplementary Fig. 9) to examine possible sample dependence. The specific heat shows negligible sample dependence, with ∣Cm(SH2)/Cm(SH1) − 1∣ ≤ 0.1 at 0 T, which falls well within the error margins of two independent ultra-low-temperature measurements. In contrast, thermal transport exhibits evident sample dependence—likely due to scattering from grain boundaries or other structural imperfections. For example, κxx(TC5)/κxx(TC4)−1 ~ 20−350 (Supplementary Fig. 10). This is reasonable given that \({\kappa }_{xx}\, \sim \,\frac{C\lambda v}{3{N}_{{{\rm{A}}}}{V}_{0}}\), where λ is highly sensitive to sample crystallinity. Very similar sample dependence in both specific heat and thermal conductivity had been reported in several other frustrated magnets, including YbMgGaO426,27,56,57 and Na2BaCo(PO4)233,34.

Thermal conductivity of the highest-quality crystal

The thermal conductivity data of sample TC5 are expected to reflect the intrinsic properties of GdZnPO for the following reasons: (1) Sample TC5 exhibit sharp Laue photographs (Supplementary Fig. 9), and a room-temperature resistivity of \({\rho }_{xx}^{{{\rm{e}}}}\)(300 K) ~ 11 kΩm over 26 times higher than those of TC1-TC4 (~0.30−0.42 kΩm, see Fig. 2b). (2) In the case of GdZnPO, the low-temperature drop in κxx/T is mainly observed in sample TC4 (see Fig. 2a), which exhibits broader Laue patterns and poorer electrical insulation (see above), suggesting that the suppression is caused by disorder effects. In contrast, sample TC5 shows no such drop. Instead, its thermal conductivity is well described by κxx ~ κ0 + κ1T + KpT3 below 1 K, across various magnetic fields up to 12 T (see Fig. 3a, b). Remarkably, in zero field, sample TC5 even exhibits an unusual upturn in κxx below ~ 0.1 K, which is highly reproducible. This upturn is suppressed by a small magnetic field of ~ 0.2 T. A similar phenomenon was previously reported in the Kitaev material Na2Co2TeO6, where the low-temperature rise in zero-field κxx/T was attributed to the recovery of thermal transport by itinerant excitations at ultra-low temperatures24. (3) From the fits, we obtained a significantly enhanced Kp ~ 0.94 WK−4 m−1 (Fig. 3b), and λp ~ 0.20 mm, which closely matches W = 0.21 mm, for sample TC5. (4) As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12d, the fitted κ0 first suddenly increases from nearly zero at 0 T to a large value at 0.5−0.6 T in samples TC1-TC3. Since C0 is already significant at 0 T (see Fig. 3f) due to the putative SSL contour, we attribute this phenomenon to a disorder effect: the excitations along the spiral contour may be scattered by abnormal spin configurations near the grain boundaries, and a weak applied field of ~ 0.5 T may suppress this scattering caused by local perturbations from crystal imperfections. In the highest-quality sample TC5, this disorder effect is absent (see Fig. 3e), and the field dependence of κ0 resembles that of C0 (see Fig. 3f), except for the sudden drop of C0 near the crossover field of ~ 12 T, which is discussed later.

a Thermal conductivity κxx of sample TC5 at various fields, with fits κxx ~ κ0 + κ1T + KpT3 below 1 K (colored lines). Fitted parameters κ0 and κ1 are shown in e (solid symbols). The vertical arrow marks the upturn onset in zero-field κxx as T decreases. b κxx/T vs T2 for selected data. The gray and black lines represent the κ0/T and κ1 + KpT2 components, respectively, of the 0.2 T fit. c, d Field dependence of κxx/T and magnetic specific heat Cm/T at selected temperatures (error bars: 1σ s.e.). e, f Field dependence of fitted parameters κ0, κ1, C0, and C1. In (e), open symbols show the fitted values of κ0 and κ1 from linear fits κxx ~ κ0 + κ1T at T ≤ 0.14 K, where the KpT3 term (≤ 0.018 WK−1 m−1) is negligible. Dashed lines in (c−f) mark the crossover field μ0Hc ~ 12 T.

The magnetic thermal conductivity, \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,{\kappa }_{0}+{\kappa }_{1}T\), is also significantly enhanced in the highest-quality sample TC5, with κ0 ~ 0.05−0.28 WK−1 m−1 and κ1 ~ 0.25−0.97 WK−2 m−1 across 0−12 T (see Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 12). In conventionally condensed states, the specific heat (C) and thermal conductivity (κxx) of (quasi-)particles following Fermi-Dirac or Bose-Einstein statistics exhibit a low-temperature dependence of ∝ T β or \(\propto \,\exp (-\Delta /T)\), where β ≥ 1 and Δ > 0. Examples include β = 1 for fermionic systems, β = 2 for 2D antiferromagnetic bosonic systems, and Δ > 0 for gapped systems. This behavior leads to either a finite constant or a vanishing C/T and κxx/T as T → 0 K. Surprisingly, κxx/T measured on the highest-quality GdZnPO crystal TC5 exhibits a robust upturn, following κxx/T ~ κ0/T + κ1 + KpT2 below ~ 1 K (see Fig. 3b). Across fields up to 12 T, the magnetic thermal conductivity, \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,{\kappa }_{0}+{\kappa }_{1}T\), aligns with the magnetic specific heat behavior, Cm ~ C1T + C0 (Fig. 1c), consistent with the relation \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\propto {C}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\). For excitations along and off the putative SSL contour, we obtained λm0vm0 ~ 3NAV0κ0/C0 ~ 7.1−150 mm2 s−1, and λm1vm1 ~ 3NAV0κ1/C1 ~ 8.8−70 mm2 s−1 for sample TC5, depending on the applied magnetic field (see Supplementary Fig. 13)—values significantly smaller than the phonon parameter λpvp ~ 0.57 m2 s−1. Using the mean magnon velocity calculated from spin-wave theory for spin excitations off the SSL contour, vm1 ~ 110 ms−1 (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 9, 10), we estimated λm1 ~ 0.5 μm for the highest-quality sample TC5 at 0 T—a value more than three orders of magnitude larger than the lattice constant a ~ 3.9 Å, supporting the high mobility of low-energy spin excitations.

Along the SSL contour, the group velocity \({v}_{{{\rm{m0}}}}\, \sim \,{\nabla }_{{{{\bf{Q}}}}_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\omega\) (where ℏω is the excitation energy) is expected to be small due to ground-state degeneracy. However, weak quantum fluctuations from S = 7/2 and perturbations beyond the classical easy-plane frustrated honeycomb model may slightly lift this degeneracy, resulting in a nonzero vm0 in GdZnPO. This likely explains why the measured λm0vm0 is nonzero.

At low temperatures, κxx/T decreases with increasing field and exhibits a broad hump around 6 T, while Cm/T remains nearly constant up to ~ 11 T before showing a sharp drop near the crossover field μ0Hc ~ 12 T in agreement with spin-wave calculations (see Figs. 3c, d, 4b). Since the low-temperature (~ 0.1 K) heat transport is dominated by spin excitations along the spiral contour, the observed hump in κxx/T near 6 T and the drop in Cm/T near μ0Hc are mainly governed by the residual terms κ0 and C0, respectively (Fig. 3e, f). Within a quasiparticle framework, the distinct field dependencies of κ0 and C0 arise from variations in the product λm0vm0, which is generally field-dependent. Even at μ0Hc ~ 12 T, the GdZnPO spin system is not fully polarized, as indicated by the measured susceptibility dM/dH remaining larger than the Van Vleck value ( \({\chi }_{{{\rm{vv}}}}^{\parallel }\) = 0.3 cm3/mol)15 at 50 mK (Supplementary Fig. 13), likely due to quantum fluctuations associated with the finite spin quantum number S = 7/2. As a result, both κ0 and C0 are significantly suppressed but remain finite at 12 T (see Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 13c, d). The absence of a sharp drop in κ0 suggests a sudden enhancement in the mean free path and/or group velocity of the excitations along the spiral contour, i.e., in λm0vm0, likely driven by quantum fluctuations near μ0Hc (see Supplementary Fig. 13e). In contrast, the linear term κ1 (Fig. 3e), and thus λm1vm1, gradually decreases with increasing field up to 12 T, in rough agreement with the field dependence of the mean magnon velocity calculated for excitations off the SSL contour (see Supplementary Fig. 18c). While current models of magnetic thermal transport remain limited, the temperature and field dependence of Cm is qualitatively captured by spin-wave theory and Monte Carlo simulations (Fig. 4a, b).

a Specific heat (\({C}_{{{\rm{m}}}}^{{{\rm{cal}}}}\)) calculated using spin-wave (SW) theory and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations. The black line represents the \({C}_{{{\rm{m}}}}^{{{\rm{cal}}}}\) = R/2 behavior, while the olive line depicts a linear fit to the MC data using \({C}_{{{\rm{m}}}}^{{{\rm{cal}}}}\) = \({C}_{0}^{{{\rm{cal}}}}\) + \({C}_{1}^{{{\rm{cal}}}}T\). The crossover temperature T* is indicated. b Field dependence of \({C}_{{{\rm{m}}}}^{{{\rm{cal}}}}\) at 0.1 K. The dashed line marks the crossover field μ0Hc ~ 12 T. c Temperature dependence of κxy/T at selected magnetic fields. d Magnetic field dependence of κxy/T measured at selected temperatures. In (c, d) error bars, 1σ s.e.

Thermal Hall effect

The thermal Hall effect serves as a powerful probe of spin excitations58,59,60,61,62,63. Figure 4c presents the thermal Hall conductivity, κxy/T, measured on the high-quality GdZnPO sample TC2 with a magnetic field applied along the c axis. At ~ 1.5 K—well below the representative phonon Debye temperature ΘD ~ 117.5 K—a clear positive κxy/T is observed (Fig. 4c), and is expected to significantly exceed the phonon contribution64. Given that the Zeeman energy associated with ~ 12 T is only ~ 10 K, much smaller than the phonon energy scale (> 100 K), a linear field dependence of the phonon thermal Hall conductivity, \({\kappa }_{xy}^{{{\rm{p}}}}\, \sim \,a{\mu }_{0}H\), is generally expected below 12 T within the linear response regime, where a is a constant64,65,66. Through a linear fit to the measured κxy between ~ 6 and 12 T, the estimated phonon contribution, aμ0H, remains significantly smaller than κxy across the entire field range (see Supplementary Fig. 15c). Since GdZnPO is an insulator, the observed κxy/T is expected to predominantly arise from spin excitations. The residual value of observed κxy/T approaches zero below ~ 0.8 K (Fig. 4c), supporting a dominate bosonic origin62,63. On the honeycomb lattice, each unit cell contains two spins (see Fig. 1b), resulting in two bands. The temperature dependence of κxy/T can be approximated by the two-flat-band bosonic model63, with the lower band’s Chern number Cs ~ 1 (Supplementary Fig. 15a), supporting the topological nature of (at least some) spin excitations in GdZnPO.

As shown in Fig. 4d, κxy/T exhibits a peak at ~ 2.5 T, a feature strikingly similar to that recently observed in the SSL candidate MnSc2S4 at comparably low temperatures67. In that system, the peak has been attributed to a magnon thermal Hall effect arising from antiferromagnetic skyrmions at high fields. In GdZnPO, the classical easy-plane frustrated honeycomb model also supports spin and momentum vortices with nonzero winding numbers at finite fields15, which may contribute to the observed thermal Hall effect (see Fig. 4c, d). Possible origins are further discussed in the next section. An oscillation-like feature in κxy/T appears at 1.5 K (see Fig. 4d), but no clear periodicity in μ0H, \({\mu }_{0}^{-1}{H}^{-1}\) 68, or log10(μ0H) is identified (see Supplementary Fig. 15). In addition, the pattern of κxy/T changes noticeably above ~ 4 T at a different temperature (see Fig. 4d), further suggesting that the apparent oscillations likely stem from ordinary measurement noise.

Discussion

The existence of nonzero magnetic thermal conductivity in the low-T limit, κ1, remains a debated topic among various magnetic insulators, including prominent spin-liquid candidates, as shown in Fig. 523,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. The triangular-lattice spin-liquid candidate 1T-TaS2 achieves a high reported value of κ1 ≤ 50 mWK−2 m−1 44, though this remains a topic of debate45. Notably, 1T-TaS2 exhibits a resistivity below 1 Ωm down to 0.5 K44, over three orders of magnitude smaller than that of GdZnPO (Fig. 2b). Similarly, the spin-liquid candidate κ-H3(Cat-EDT-TTF)2 exhibits a comparably high value of κ1 ~ 60 mWK−2 m−1 32. Consequently, GdZnPO emerges as a rare magnetic insulator with remarkably high intrinsic magnetic thermal conductivity, following \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,{\kappa }_{1}T\) + κ0 in the low-T limit, with κ1 ~ 970 mWK−2 m−1 (see Fig. 3b) and κ0 ~ 250 mWK−1 m−1 (see Fig. 3a) at ~ 0 T from the highest-quality crystal TC5. The observed thermal conductivity in the low-T limit, κ1, is exceptionally large compared to the other magnetic insulators (see Fig. 5). More importantly, the substantial residual thermal conductivity κ0 (at ~ 0 T), attributed to spin excitations along the putative SSL contour in GdZnPO, has not been reported in other magnetic insulators to the best of our knowledge. These findings suggest the presence of intrinsic, mobile, high-density low-energy spin excitations and the stability of the putative SSL, without order by disorder, down to at least ~ 0.05 K in GdZnPO.

Previously reported κ1 or low-temperature κxx/T values are shown for various magnetic insulators, including two-dimensional honeycomb α-RuCl323 and Na2Co2TeO624,25; two-dimensional triangular-lattice YbMgGaO426,27, EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]229,30,31, κ-H3(Cat-EDT-TTF)232, Na2BaCo(PO4)233,34, BaFe12O1936, and 1T-TaS244,45; two-dimensional kagome ZnCu3(OH)6Cl237, CaCu3(OH)6Cl2⋅0.6H2O38, and YCu3(OH)6.5Br2.539; three-dimensional (3D) Yb2Ti2O741 and PbCuTe2O642; and one-dimensional (1D) antiferromagnetic Cu(C6H5COO)2⋅3H2O43.

Because of the strong neutron absorption by Gd atoms, neutron scattering measurements on GdZnPO remain challenging. Nevertheless, several experimental observations support the emergence of an SSL in GdZnPO at low temperatures: (1) Low-temperature magnetization measurements clearly reveal easy-plane anisotropy. Combined with the crystal structure and magnetization data, the spin system of GdZnPO is well described by the S = 7/2 easy-plane J1-J2 honeycomb-lattice model15. Theoretically, an SSL is stabilized within this model across a broad parameter range, ∣J2/J1∣ > 1/6, persisting down to very low temperatures14. Furthermore, the experimentally determined Hamiltonian yields a crossover field of μ0Hc ~ 12 T and a Curie-Weiss temperature of θw = −S(S + 1)(J1 + 2J2) ~ −12 K, both of which are in good agreement with the experimental results on GdZnPO (see Fig. 3d, f )15. (2) Within the spherical approximation, the generic SSL theory predicts a low-temperature magnetic specific heat of Cm ~ C0 + C1T 8—a distinctive behavior not reported in other spin systems to our knowledge. Experimentally, GdZnPO exhibits this feature at low temperatures up to the crossover field μ0Hc ~ 12 T, see Fig. 1c. (3) Within the SSL ansatz on the honeycomb lattice, the zero-temperature susceptibility is theoretically predicted to be constant up to ~ μ0Hc: \({\chi }_{{{\rm{cal}}}}^{\parallel }\) = \({\mu }_{0}{N}_{{{\rm{A}}}}{g}^{2}{\mu }_{{{\rm{B}}}}^{2}/[2D+3{J}_{1}+9{J}_{2}+{J}_{1}^{2}/(4{J}_{2})]\) + \({\chi }_{{{\rm{vv}}}}^{\parallel }\) (~ 4.4 cm3/mol), consistent with the experimental observations down to 50 mK (~ 0.4%∣θw∣, see Supplementary Figs. 13a, 14a). (4) The giant magnetocaloric effect observed in GdZnPO is well explained by the determined easy-plane J1-J2 honeycomb-lattice spin Hamiltonian without tuning parameters22. (5) As shown in Fig. 3a, b, the temperature dependence of thermal conductivity closely follows the expected form κxx = κ0 + κ1T + KpT3 below 1 K and up to the crossover field μ0Hc ~ 12 T. Within the quasi-particle framework, the magnetic thermal conductivity is proportional to the magnetic specific heat, i.e., \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\) (~ κ0 + κ1T) ∝ Cm. Notably, the observation of a magnetic contribution \({\kappa }_{xx}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\, \sim \,{\kappa }_{0}+{\kappa }_{1}T\) is highly distinctive and, to our knowledge, has not been reported in any other magnetic compound. This unusual thermal transport behavior further substantiates the emergence of an SSL in GdZnPO.

In the ordered phases of the pure easy-plane frustrated honeycomb model, linear spin-wave bands possess zero Chern numbers, implying no thermal Hall effect11. Thus, the positive thermal Hall effect observed in GdZnPO may stem from several factors: (1) The calculations11 assume perfect SSL ground-state configurations, while low-energy topological excitations, like spin and momentum vortices, emerge at low temperatures15, potentially yielding nonzero Chern numbers for the magnon bands via a fictitious magnetic flux69. These topological excitations may also contribute directly to the thermal Hall effect above ~ 1.2 K (Fig. 4c) through a momentum-transfer force70 if they are mobile. (2) Weak perturbations, such as symmetrically allowed (Fig. 1a) DM interactions, may induce nonzero Chern numbers and a magnon thermal Hall effect11. (3) The low-energy structure of the spiral contour may accommodate other thermal excitations that contribute to thermal Hall transport. (4) While the calculations are classical11, GdZnPO’s S = 7/2 system exhibits weak quantum fluctuations.

The putative 2D SSL in the frustrated honeycomb-lattice antiferromagnet GdZnPO has been shown to persist from T* ~ 2 K down to ~ 0.053 K, confirming its stability with a high density of low-energy spin excitations at H < Hc15. This work further demonstrates that these excitations are not only mobile but also at least partially topological, as evidenced by the observed giant low-temperature thermal conductivity (down to ~ 0.05 K) and positive thermal Hall effect. These findings provide new avenues for exploring the exotic transport and topological properties of low-lying excitations in SSL candidates.

Methods

GdZnPO single crystals were grown using the flux method15. Despite nearly identical synthesis procedures, the crystal sizes, Laue FWHMs, electric resistivities, and low-temperature thermal conductivities vary significantly between samples (see Fig. 2). In contrast, the low-temperature specific heat shows weak sample dependence across all three measured samples, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. The as-grown oxide single crystals of GdZnPO are very thin (thickness ≲ 0.1 mm) and mechanically fragile. High-resolution measurements of both thermal conductivity and specific heat require relatively large crystals—with length ≳ 1 mm or mass ≳ 1 mg. Unfortunately, crystals often broke into smaller fragments during the careful removal of silver paste (used in thermal conductivity measurements) or GE varnish (used in specific heat measurements), making it impractical at present to measure both properties on the same GdZnPO crystal. Sample TC3 was confirmed to have broken during the thermal-conductivity experiment at fields above ~ 6 T due to the torque induced by the easy-plane anisotropy of the spin system, and thus, we failed to collect its higher-field data.

The as-grown crystals’ longest dimension aligns with the [110] direction, as determined by Laue XRD, and thermal or electrical currents were applied along this direction (Fig. 1b). Longitudinal thermal conductivity and thermal Hall conductivity were measured using standard four- and five-wire steady-state methods54, respectively, in magnetic fields up to 12 T along the c axis and temperatures ranging from 0.05 to 2 K, achieved with a superconducting magnet and a 3He-4He dilution refrigerator (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1−12). We employed a cantilever-based thermal conductivity setup that was thermally isolated from all supporting components, with only minor additional heat flow occurring primarily through the NbTi superconducting leads (13 mm in length and 63 μm in diameter) connected to the heater and thermometers (Supplementary Fig. 7c). The resulting heat-leakage conductance is negligibly small, as detailed in Supplementary Note 1.

Specific heat down to 43 mK and magnetization down to 50 mK were also measured in the 3He-4He dilution refrigerator15. Crystal quality was accessed via the FWHM of Laue XRD reflections measured under identical conditions. Electrical resistance measurements were conducted using a PPMS (Quantum Design). Linear spin-wave theory was employed to simulate the specific heat and mean magnon velocity using the previously determined GdZnPO Hamiltonian15, without parameter tuning (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 17, 18). Standard MC simulations of the specific heat were performed on a 2 × 602 cluster with periodic boundary conditions, using the same Hamiltonian. Each simulation comprised 15,000 MC steps at each of 200 temperatures, annealing gradually from 50 K to 0.05 K, with 5000 steps allocated for thermalization.

Data availability

The data generated within the main text are provided in the Source Data. Additional raw data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Savary, L. & Balents, L. Quantum spin liquids: a review. Rep. Prog. Phy. 80, 016502 (2016).

Zhou, Y., Kanoda, K. & Ng, T.-K. Quantum spin liquid states. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 025003 (2017).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083 (2008).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231 (2016).

Gao, S. et al. Fractional antiferromagnetic skyrmion lattice induced by anisotropic couplings. Nature 586, 37 (2020).

Lee, P. A., Nagaosa, N. & Wen, X.-G. Doping a Mott insulator: physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17 (2006).

Bergman, D., Alicea, J., Gull, E., Trebst, S. & Balents, L. Order-by-disorder and spiral spin-liquid in frustrated diamond-lattice antiferromagnets. Nat. Phys. 3, 487 (2007).

Yao, X.-P., Liu, J. Q., Huang, C.-J., Wang, X. & Chen, G. Generic spiral spin liquids. Front. Phys. 16, 53303 (2021).

Mulder, A., Ganesh, R., Capriotti, L. & Paramekanti, A. Spiral order by disorder and lattice nematic order in a frustrated Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the honeycomb lattice. Phys. Rev. B 81, 214419 (2010).

Owerre, S. A. Topological magnon bands and unconventional thermal Hall effect on the frustrated honeycomb and bilayer triangular lattice. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 385801 (2017).

Fujiwara, K., Kitamura, S. & Morimoto, T. Thermal Hall responses in frustrated honeycomb spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 106, 035113 (2022).

Okumura, S., Kawamura, H., Okubo, T. & Motome, Y. Novel spin-liquid states in the frustrated Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the honeycomb lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 114705 (2010).

Shimokawa, T., Okubo, T. & Kawamura, H. Multiple-q states of the J1 − J2 classical honeycomb-lattice Heisenberg antiferromagnet under a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 100, 224404 (2019).

Huang, C.-J., Liu, J. Q. & Chen, G. Spiral spin liquid behavior and persistent reciprocal kagome structure in frustrated van der Waals magnets and beyond. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013121 (2022).

Wan, Z. et al. Spiral spin liquid in a frustrated honeycomb antiferromagnet: a single-crystal study of GdZnPO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 236704 (2024).

Yao, N. Y. et al. Topologically protected quantum state transfer in a chiral spin liquid. Nat. Commun. 4, 1585 (2013).

Pretko, M. Subdimensional particle structure of higher rank U(1) spin liquids. Phys. Rev. B 95, 115139 (2017).

Nandkishore, R. M. & Hermele, M. Fractons. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 295 (2019).

Pretko, M., Chen, X. & You, Y. Fracton phases of matter. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 35, 2030003 (2020).

Yan, H. & Reuther, J. Low-energy structure of spiral spin liquids. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023175 (2022).

Hsieh, T.-C. & Radzihovsky, L. O(N) smectic σ model. Phys. Rev. B 108, 224423 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Chen, X., Wan, Z., Ma, Z. & Li, Y. Giant magnetocaloric effect in a honeycomb-lattice spiral spin liquid candidate. Adv. Sci. e10086 (2025).

Yu, Y. J. et al. Ultralow-temperature thermal conductivity of the Kitaev honeycomb magnet α-RuCl3 across the field-induced phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 067202 (2018).

Guang, S. et al. Thermal transport of fractionalized antiferromagnetic and field-induced states in the Kitaev material Na2Co2TeO6. Phys. Rev. B 107, 184423 (2023).

Hong, X. et al. Phonon thermal transport shaped by strong spin-phonon scattering in a Kitaev material Na2Co2TeO6. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 18 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Absence of magnetic thermal conductivity in the quantum spin-liquid candidate YbMgGaO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 267202 (2016).

Rao, X. et al. Survival of itinerant excitations and quantum spin state transitions in YbMgGaO4 with chemical disorder. Nat. Commun. 12, 4949 (2021).

Yamashita, M. et al. Highly mobile gapless excitations in a two-dimensional candidate quantum spin liquid. Science 328, 1246 (2010).

Bourgeois-Hope, P. et al. Thermal conductivity of the quantum spin liquid candidate EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2: No evidence of mobile gapless excitations. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041051 (2019).

Ni, J. M. et al. Absence of magnetic thermal conductivity in the quantum spin liquid candidate EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 247204 (2019).

Yamashita, M. et al. Presence and absence of itinerant gapless excitations in the quantum spin liquid candidate EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2. Phys. Rev. B 101, 140407 (2020).

Shimozawa, M. et al. Quantum-disordered state of magnetic and electric dipoles in an organic Mott system. Nat. Commun. 8, 1821 (2017).

Li, N. et al. Possible itinerant excitations and quantum spin state transitions in the effective spin-1/2 triangular-lattice antiferromagnet Na2BaCo(PO4)2. Nat. Commun. 11, 4216 (2020).

Huang, Y. Y. et al. Thermal conductivity of triangular-lattice antiferromagnet Na2BaCo(PO4)2: Absence of itinerant fermionic excitations. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.08866 (2022).

Li, N. et al. Quantum spin state transitions in the spin-1 equilateral triangular lattice antiferromagnet Na2BaNi(PO4)2. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104403 (2021).

Shen, S.-P. et al. Quantum electric-dipole liquid on a triangular lattice. Nat. Commun. 7, 10569 (2016).

Huang, Y. Y. et al. Heat transport in herbertsmithite: can a quantum spin liquid survive disorder? Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 267202 (2021).

Doki, H. et al. Spin thermal Hall conductivity of a kagome antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 097203 (2018).

Hong, X. et al. Heat transport of the kagome Heisenberg quantum spin liquid candidate YCu3(OH)6.5Br2.5: Localized magnetic excitations and a putative spin gap. Phys. Rev. B 106, L220406 (2022).

Jeon, S. et al. One-ninth magnetization plateau stabilized by spin entanglement in a kagome antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 20, 435 (2024).

Tokiwa, Y. et al. Possible observation of highly itinerant quantum magnetic monopoles in the frustrated pyrochlore Yb2Ti2O7. Nat. Commun. 7, 10807 (2016).

Hong, X. et al. Spinon heat transport in the three-dimensional quantum magnet PbCuTe2O6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 256701 (2023).

Pan, B. Y. et al. Unambiguous experimental verification of linear-in-temperature spinon thermal conductivity in an antiferromagnetic Heisenberg chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 167201 (2022).

Murayama, H. et al. Effect of quenched disorder on the quantum spin liquid state of the triangular-lattice antiferromagnet 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013099 (2020).

Yu, Y. J. et al. Heat transport study of the spin liquid candidate 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081111 (2017).

Nientiedt, A. T. & Jeitschko, W. Equiatomic quaternary rare earth element zinc pnictide oxides RZnPO and RZnAsO. Inorg. Chem. 37, 386 (1998).

Lincke, H. et al. Magnetic, optical, and electronic properties of the phosphide oxides REZnPO (RE = Y, La-Nd, Sm, Gd, Dy, Ho). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 634, 1339 (2008).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

Xiong, J. et al. High-field Shubnikov–de Haas oscillations in the topological insulator Bi2Te2Se. Phys. Rev. B 86, 045314 (2012).

Liu, J. et al. Gapless spin liquid behavior in a kagome Heisenberg antiferromagnet with randomly distributed hexagons of alternate bonds. Phys. Rev. B 105, 024418 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Frustrated magnetism of the triangular-lattice antiferromagnets α-CrOOH and α-CrOOD. New J. Phys. 23, 033040 (2021).

Gofryk, K. et al. Anisotropic thermal conductivity in uranium dioxide. Nat. Commun. 5, 4551 (2014).

Hong, X. et al. Strongly scattered phonon heat transport of the candidate Kitaev material Na2Co2TeO6. Phys. Rev. B 104, 144426 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Quantum annealing of a frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 15, 3495 (2024).

Toews, W. H. et al. Thermal conductivity of Ho2Ti2O7 along the [111] direction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 217209 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Gapless quantum spin liquid ground state in the two-dimensional spin-1/2 triangular antiferromagnet YbMgGaO4. Sci. Rep. 5, 16419 (2015).

Paddison, J. A. M. et al. Continuous excitations of the triangular-lattice quantum spin liquid YbMgGaO4. Nat. Phys. 13, 117 (2017).

Onose, Y. et al. Observation of the magnon Hall effect. Science 329, 297 (2010).

Hirschberger, M., Krizan, J. W., Cava, R. J. & Ong, N. P. Large thermal Hall conductivity of neutral spin excitations in a frustrated quantum magnet. Science 348, 106 (2015).

Katsura, H., Nagaosa, N. & Lee, P. A. Theory of the thermal Hall effect in quantum magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 066403 (2010).

Kasahara, Y. et al. Majorana quantization and half-integer thermal quantum Hall effect in a Kitaev spin liquid. Nature 559, 227 (2018).

Yang, Y., Zhang, G. & Zhang, F. Universal behavior of the thermal Hall conductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 186602 (2020).

Czajka, P. et al. Planar thermal Hall effect of topological bosons in the Kitaev magnet α-RuCl3. Nat. Mater. 22, 36 (2023).

Li, X., Fauqué, B., Zhu, Z. & Behnia, K. Phonon thermal Hall effect in strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 105901 (2020).

Strohm, C., Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Wyder, P. Phenomenological evidence for the phonon Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 155901 (2005).

Sugii, K. et al. Thermal Hall effect in a phonon-glass Ba3CuSb2O9. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 145902 (2017).

Takeda, H. et al. Magnon thermal Hall effect via emergent SU(3) flux on the antiferromagnetic skyrmion lattice. Nat. Commun. 15, 566 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Large oscillatory thermal hall effect in kagome metals. Nat. Commun. 15, 6224 (2024).

Mascot, E., Bedow, J., Graham, M., Rachel, S. & Morr, D. K. Topological superconductivity in skyrmion lattices. npj Quantum Mater. 6, 6 (2021).

Schütte, C. & Garst, M. Magnon-skyrmion scattering in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 90, 094423 (2014).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Xiaokang Li, Shang Gao, Zhengxin Liu, Changle Liu, and Haijun Liao for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2024YFA1613100 (Y.L.) and 2023YFA1406500 (Y.L.)), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12274153 (Y.L.)), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. HUST: 2020kfyXJJS054 (Y.L.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. planned and supervised the project. Y.Z. and Y.L. collected the thermal transport, specific heat, Laue x-ray diffraction, and electrical resistance data. X.C., Z.W., and Z.M. prepared the GdZnPO single crystals. Y.L. and X.C. conducted the spin-wave calculations and Monte Carlo simulations. Y.L., Y.Z., X.Y., and X.H. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with comments from all co-authors. The manuscript reflects the contributions of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Young Sun, Minoru Yamashita and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Yao, X., Chen, X. et al. Itinerant and topological excitations in a honeycomb spiral spin liquid candidate. Nat Commun 16, 8410 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63620-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63620-x