Abstract

Insulin resistance is suggested to be a risk factor for cancer; however, large-scale epidemiological evidence linking insulin resistance to cancer remains limited. Here we apply a machine learning-based prediction model of insulin resistance with nine clinical parameters, termed artificial intelligence–derived insulin resistance (AI-IR), to the UK Biobank and demonstrated that AI-IR exhibits the highest predictive performance for diabetes incidence compared to body mass index (BMI), metabolic syndrome (MetS), triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TG/HDL) ratio, and triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index. Moreover, AI-IR is significantly associated with an increased risk of six cancers (uterine, kidney, esophagus, pancreas, colon, and breast) and showed nominal associations with six additional cancers (renal pelvis, small intestine, stomach, liver and gallbladder, leukemia, and bronchial and lung). When we define composite cancers by merging cancer types whose risks increase with AI-IR, age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio is 1.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.20-1.31; P < 1 ×10-11). AI-IR is a better predictor of the composite cancers compared to BMI and TyG index, while its capability is comparable to that of MetS and TG/HDL ratio. We conclude that AI-IR is a robust metric for predicting both diabetes and the composite cancer incidence and could be utilized for identification of high-risk individuals and focused screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insulin resistance, defined as an impaired response of tissues such as liver, muscle, and adipose tissue to insulin1, is one of the fundamental etiologies of diabetes along with impaired insulin secretion. Indeed, insulin resistance precedes the development of type 2 diabetes1 and also predisposes people to cardiovascular disease2. Insulin resistance is often caused by obesity and its associated chronic inflammation, and is accompanied by compensatory hyperinsulinemia.

Accumulating evidence indicates that both diabetes3,4,5 and obesity6,7,8 are associated with a higher risk of cancer. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that insulin resistance, which links diabetes and obesity, is also a risk factor for cancer. In this regard, it has been proposed that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia might contribute to cancer growth through the anabolic action of insulin and also because of cross-reactivity of insulin with insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor9. The mechanistic link between inflammation and cancer has also been actively investigated10. Similarly, metabolic syndrome, which is linked to visceral adiposity and its associated insulin resistance11, is also associated with a higher risk of cancer12,13,14,15,16,17. However, large-scale epidemiological evidence directly linking insulin resistance and cancer is limited, with only a few studies examining the incidence of endometrial and colorectal cancer using high fasting insulin as a surrogate marker for insulin resistance18,19, because insulin resistance is rarely evaluated in patients, except for those being treated in specialized diabetes clinics. The gold standard method for assessing insulin resistance, the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, is not feasible in regular clinical settings. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index, in which the product of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and fasting plasma insulin is divided by a constant20, has been widely used as an alternative method because HOMA-IR involves the direct measurement of insulin and glucose, and has been shown to correlate strongly with the gold standard clamp technique21,22. Nevertheless, fasting plasma insulin is also not routinely evaluated in general practice. Therefore, the possible effect of insulin resistance on cancer incidence has been difficult to examine at the population scale. Recently, we developed a machine learning-based prediction model of insulin resistance (i.e., HOMA-IR > 2.5) that considers nine clinical parameters (age, sex, race, body mass index [BMI], FPG, glycohemoglobin, triglyceride [TG], total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL]) in a non-diabetic population of both European and Asian ancestries, using the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cohort and the Taiwan MJ cohort. The area under the curve of our prediction model was as high as 0.8823.

Here, we apply the machine learning-based prediction model, termed artificial intelligence–derived insulin resistance (AI-IR), to the UK Biobank cohort to examine the effect of predicted insulin resistance on the incidence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer at the population scale. AI-IR outperforms previously established metrics in predicting diabetes and is also significantly associated with specific types of cancer.

Results

Machine learning-predicted insulin resistance was associated with a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in the UK Biobank

To evaluate the predictive capability of AI-IR (Fig. 1a) for the incidence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in the UK Biobank, we first looked at the effect of AI-IR on the incidence of diabetes among participants without diabetes at baseline and completed follow-up visit (N = 14,165, baseline characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 1). During a mean follow-up of 4.28 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.41–5.15), 309 participants (2.18%) developed diabetes. AI-IR positive participants had a significantly higher risk of developing diabetes compared to AI-IR negative participants (odds ratio [OR], 7.31; 95% CI, 5.75–9.30; P < 1 × 10−10, Fig. 1b). Notably, although AI-IR was originally developed using fasting blood test results, blood samples in the UK Biobank were not consistently collected in the fasted state. To address this, we stratified participants into three groups based on fasting duration prior to blood collection (less than 4 h, 4 or more and less than 8 h, 8 h or more) and examined the association between AI-IR and the incidence of diabetes. Across all categories, AI-IR positive participants consistently showed a significantly higher risk of developing diabetes, supporting the robustness of our model (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). Hereafter, to maintain maximum sample size, we did not stratify or exclude participants based on fasting duration. In a complementary analysis leveraging the National Health Service (NHS) medical record system, we looked at the effect of AI-IR on hospital admission with diabetes among participants without diabetes at baseline (Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Supplementary Table 2). AI-IR positive participants had a markedly higher risk of admission with diabetes (hazard ratio [HR], 6.44; 95% CI, 6.19–6.69; P < 1 × 10−10, Fig. 1c). Of note, AI-IR was associated with a significantly higher risk of diabetes onset and hospital admission with diabetes after adjusting for age and sex, and even after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI, indicating that our machine learning-based prediction model is able to capture a BMI-independent effect of insulin resistance (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b).

a A diagram depicting the construction of a machine learning model to predict insulin resistance (HOMA-IR > 2.5) that uses nine clinical parameters. b Effect of AI-IR on the odds ratio (OR) for onset of diabetes during the follow-up period in participants without diabetes (DM) at baseline. Logistic regression was used with a two-sided Wald test. In the graph, points represent the estimated OR, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. c Effect of AI-IR on the hazard ratio (HR) for hospital admission due to diabetes in participants without DM at baseline. Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. In the graph, points represent the estimated HR, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. d, e Kaplan–Meier plot for cumulative incidence of 3-point MACE (d) or cardiovascular mortality (e) in DM (-); AI-IR (-), DM(-); AI-IR (+), and DM (+) group. In the graph, the lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence, and the shaded error bands represent 95% confidence intervals. The HRs adjusted for age and sex are also shown for 3-point MACE (d) and cardiovascular mortality (e). Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Cardiovascular disease is a major complication of insulin resistance and diabetes. Therefore, we also looked at the effect of AI-IR on 3- and 4-point major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE). Effects on cardiovascular mortality and overall mortality were also examined. Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Supplementary Table 2. As expected, a Kaplan-Meier plot revealed a significant difference in the cumulative incidence of 3-point MACE between participants with diabetes, those without diabetes but positive for AI-IR, and those without diabetes and negative for AI-IR (Fig. 1d, log-rank test P < 1 × 10−10). The HR adjusted for age and sex was highest in participants with diabetes (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.76-1.92; P < 1 × 10−10), followed by those without diabetes but positive for AI-IR (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.34–1.42; P < 1 × 10−10), and then those without diabetes and negative for AI-IR (Fig. 1d). AI-IR and diabetes was significantly associated with a higher risk of 3-point MACE even after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI (Supplementary Fig. 2c). We also observed that AI-IR was significantly associated with an increased risk of 4-point MACE, cardiovascular mortality, and overall mortality (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 2d–f).

Machine learning-predicted insulin resistance enables improved diabetes risk stratification compared to previously reported metrics

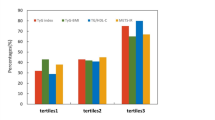

To examine whether AI-IR outperforms previously established simpler metrics of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance, we compared the predictive capabilities of AI-IR, BMI, metabolic syndrome (MetS), TG/HDL ratio, and TyG index for the incidence of diabetes among individuals without diabetes at baseline during the follow-up period. TG/HDL ratio24,25 and TyG index26,27,28 has been reported as surrogate markers of insulin resistance. Area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was highest for AI-IR (0.798, P < 1 × 10−4 vs other metrics), followed by MetS (0.748), BMI (0.721), TyG index (0.703), and TG/HDL ratio (0.702), indicating the AI-IR demonstrated the highest predictive performance among these metrics (Fig. 2a). Next, we categorized individuals without diabetes at baseline into four groups according to both AI-IR status (positive or negative) and their status on previously established metrics (positive or negative). BMI of 30, TG/HDL ratio of 3.025, and TyG index of 4.6827 were used as cut-off values according to previous literatures. When we categorized individuals into four groups based on AI-IR status (positive or negative) and BMI ( ≥ 30 or <30), we observed that the incidence of diabetes was significantly higher (P = 2.52 × 10−5) in the AI-IR single-positive group (OR, 6.14; 95% CI, 4.42–8.54; P < 1 × 10−20; adjusted for age and sex) compared with the BMI single-positive group (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.35–2.12; P = 0.74). Of note, a BMI of 30 or higher alone did not significantly increase diabetes incidence when individuals were negative for AI-IR, suggesting that these subjects may represent a metabolically healthy obesity phenotype. In contrast, diabetes incidence was markedly higher (P = 9.78 × 10−7) in the AI-IR and BMI double-positive group (OR, 8.08; 95% CI 6.13–10.66; P < 1 × 10−20) compared with the BMI single positive group, underscoring that AI-IR provides substantially improved diabetes risk stratification among individuals with obesity (BMI ≥ 30; Fig. 2b). Similarly, when we categorized individuals without diabetes into four groups based on both AI-IR status (positive or negative) and MetS (positive or negative), the incidence of diabetes was significantly higher (P = 1.55 × 10−3) in the AI-IR single-positive group (OR, 6.85; 95% CI, 4.35–10.80; P = 1.2 × 10−16) compared with the MetS single-positive group (OR, 3.14; 95% CI, 2.07–4.77; P = 6.8 × 10−8). Again, the incidence of diabetes was even greater (P = 2.19 × 10−13) in the AI-IR and MetS double-positive group (OR, 11.71; 95% CI 8.53–16.06; P < 1 × 10−20) compared with the MetS single-positive group (Fig. 2c). We observed the same pattern for TG/HDL ratio and TyG index (Fig. 2d, e). Collectively, these results indicated that AI-IR was significantly associated with a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in the UK Biobank population. Moreover, AI-IR demonstrated the highest predictive capability for the incidence of diabetes compared to previously established metrics, providing the rationale for investigating the association between predicted insulin resistance and cancer incidence in subsequent analyses.

a Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve illustrating the predictive performance of AI-IR, BMI, Metabolic Syndrome, TG/HDL ratio, and TyG index for the incidence of diabetes during the follow-up period. The area under the curve (AUC) for each metrics is also shown. b–e Effect of AI-IR and BMI (b), Metabolic syndrome (MetS) (c), TG/HDL ratio (d), or TyG index (e) on the odds ratio (OR) for onset of diabetes during the follow-up period in participants without diabetes at baseline, adjusted for age and sex. Logistic regression was used with a two-sided Wald test. In the graph, points represent the estimated OR, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Effect of machine learning-predicted insulin resistance on the incidence of cancer

To investigate the effect of AI-IR on the incidence of cancer, we leveraged the linkage between the UK Biobank and the NHS medical record system and examined the incidence of cancer among participants who were cancer-free at the baseline visit (N = 372,395). We compared participants without diabetes and negative for AI-IR (N = 256,685), those without diabetes but positive for AI-IR (N = 94,782), and those with diabetes (N = 20,928). Of 372,395 participants who were cancer-free at baseline, 51,193 developed cancer (Supplementary Table 3). When we merged all types of cancer, we did not observe any differences in cancer incidence between the three groups. The HR adjusted for age and sex in participants without diabetes but positive for AI-IR was 1.012 (95% CI, 0.992–1.033; P = 0.228), and that in participants with diabetes was 0.973 (95% CI, 0.938–1.008; P = 0.129) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4). However, when we looked at individual types of cancer, both AI-IR and diabetes were associated with a significantly higher risk of incidence of multiple cancer types (The results of the 25 common cancers are shown in Fig. 3, and the complete list can be found in Supplementary Table 4). We examined the incidence of 36 cancers common to both males and females, 4 cancer types specific to males, and 3 cancer types specific to females. The Bonferroni-corrected P value for significance was 0.05/43 = 1.163 × 10−3. The effect of AI-IR on increasing the risk of the incidence was strongest for uterine cancer (HR; 2.340; 95% CI, 2.065-2.652; P = 1.00 × 10−9), followed by kidney cancer (HR, 1.557; 95% CI, 1.367–1.772; P = 1.00 × 10−9) and esophagus cancer (HR, 1.464; 95% CI, 1.253–1.710; P = 1.61 × 10−6). It was also associated with a higher incidence of renal pelvis cancer (HR, 1.417; 95% CI, 1.013–1.983; P = 0.0418), small intestine cancer (HR, 1.393; 95% CI, 1.019–1.905; P = 0.0376), stomach cancer (HR, 1.374; 95% CI, 1.132–1.667; P = 1.28 × 10−3), liver and gallbladder (GB) cancer (HR, 1.367; 95% CI, 1.114–1.678; P = 2.73 × 10−3), pancreas cancer (HR, 1.291; 95% CI, 1.117–1.492; P = 5.58 × 10−4), colon cancer (HR, 1.176; 95% CI, 1.084–1.276; P = 9.45 × 10−5), leukemia (HR, 1.164; 95% CI, 1.012–1.339; P = 0.0337), bronchial and lung cancer (HR, 1.136; 95% CI, 1.048–1.231; P = 2.02 × 10−3), and breast cancer (HR, 1.135; 95% CI, 1.075–1.199; P = 5.92 × 10−6). When we considered the Bonferroni correction, AI-IR was associated with a higher incidence of uterine, kidney, esophagus, pancreas, colon, and breast cancers. On the other hand, AI-IR was associated with a significantly lower incidence of skin cancer (HR, 0.852; 95% CI, 0.825–0.881; P = 1.00 × 10−9). For cancer types whose incidences were increased or decreased by AI-IR, diabetes also exhibited an effect in the same direction, whereby in many cases, the effect size was numerically larger (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4).

a Effect of AI-IR and diabetes on the incidence of overall and 25 common cancers. Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. In the graph, points represent the estimated HR, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The HRs for indicated cancers, adjusted for age and sex were shown. For male-specific (prostate) or female-specific (uterine and ovary) cancers, HRs were adjusted only for age. The Bonferroni-corrected P value for significance was 0.05/43 = 1.163 × 10−3. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

When we defined composite cancers by merging 10 cancer types (common to both males and females) whose risks were either significantly increased (kidney, esophagus, pancreas, colon) or nominally increased (renal pelvis, small intestine, stomach, liver and GB, colon, and bronchial and lung) by AI-IR, a Kaplan–Meier plot revealed a significant difference between participants with diabetes, those without diabetes but positive for AI-IR, and those without diabetes and negative for AI-IR, on the cumulative incidence of the composite cancers (Fig. 4a). The HR adjusted for age and sex in participants without diabetes but positive for AI-IR was 1.25 (95% CI, 1.20–1.31; P < 1 × 10−11), and that in participants with diabetes was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.31–1.50; P < 1 × 10−11). When we adjusted also for BMI, the HR in participants without diabetes but positive for AI-IR was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.10–1.22; P = 1.2 × 10−8), suggesting that approximately 36% of AI-IR’ effect is mediated through BMI. Sex-specific analysis revealed that the impact of AI-IR on the incidence of the composite cancers remained consistent in both males and females (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). When we combined female-specific uterine and breast cancers whose risks were significantly increased by AI-IR, we observed that effect the HR adjusted for age in participants without diabetes but positive for AI-IR was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.20–1.32; P < 1 × 10−11), which was comparable to that in participants with diabetes (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11–1.36; P < 3.9 × 10−5) (Fig. 4b). A Kaplan–Meier plot also revealed a significant difference between three groups on the cumulative incidence of specific cancers such as uterine cancer (Supplementary Fig. 4a), kidney cancer, colon cancer, and bronchial and lung cancer (Supplementary Fig. 4a–d).

a Kaplan–Meier plots of the cumulative incidence of the composite cancers in the DM(-); AI-IR (-), DM(-); AI-IR (+), and DM (+) groups. In the graph, the lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence, and the shaded error bands represent 95% confidence intervals. The HRs for the incidence of the composite cancers adjusted for age and sex or adjusted for age, sex, and BMI were also shown. Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. b Kaplan–Meier plots of the cumulative incidence of the uterine and breast cancer in females from the DM(-); AI-IR (-), DM(-); AI-IR (+), and DM (+) groups. In the graph, the lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence, and the shaded error bands represent 95% confidence intervals. The HRs for the incidence of these cancers adjusted for age or adjusted for age and BMI were also shown. Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. c For 13 cancer types whose incidences were significantly or nominally affected by AI-IR, the effects of AI-IR after adjustment for BMI were shown. Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. In the graph, points represent the estimated HR, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. HRs are adjusted for age and sex. The Bonferroni-corrected P value for significance was 0.05/43 = 1.163 × 10−3. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Cancer risk is well known to increase with age29,30. Indeed, when we stratified participants by age at enrollment (40–69 years old), the incidence of the composite cancers per 1000 person-years increased with age (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Furthermore, both AI-IR and diabetes were associated with a higher incidence of the composite cancers across all ages (Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that AI-IR is the risk factor for the composite cancers across different age groups. Kaplan–Meier analyses further confirmed consistent differences in cumulative incidence of the composite cancers among three groups across different ages at enrollment (<50 years old, 50–59 years old, and ≥60 years) (Supplementary Fig. 5b–d). To more rigorously account for confounding by age, we also conducted analyses with age as the underlying time variable. Significant differences in cancer incidence persisted among participants with diabetes, those without diabetes but AI-IR positive, and those without diabetes and AI-IR negative (Supplementary Fig. 6a.) The HR adjusted for sex and BMI in participants without diabetes but AI-IR positive was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.10–1.22; P < 3.2 × 10−8), and that in participants with diabetes was 1.29 (95% CI, 1.20–1.39; P < 1 × 10−10). The effect of AI-IR on 3-point MACE was also consistent in these models (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Together, these findings demonstrate the robustness of AI-IR in predicting complications of insulin resistance while fully accounting for the effect of age.

BMI-dependent and -independent effect of machine learning-predicted insulin resistance on cancer incidence

In our prediction model, feature importance was highest for higher BMI (0.427), followed by higher FPG (0.115), lower HDL (0.115), and higher TG (0.097)23. To explore the BMI-independent effect of AI-IR on cancer incidence, we also performed an analysis adjusted for age, sex, and BMI (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 5). Among the cancers whose risks were positively associated with AI-IR, we observed that effects for renal pelvis, small intestine, stomach, liver and GB, pancreas, colon, leukemia, and breast cancer were BMI-dependent (Fig. 4c). However, we observed that the effect of AI-IR on the incidence of bronchial and lung cancer became stronger and significant even after Bonferroni correction when we adjusted for BMI in addition to age and sex (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.20–1.47; P = 1.71 × 10−8), than when we adjusted only for age and sex (HR, 1.14; 95%CI, 1.05–1.23; P = 2.02 × 10−3) (Fig. 4c), indicating that the effect was independent of BMI. The effect on uterine, kidney, and esophagus cancer remained nominally significant. Additionally, the association between AI-IR and lower risk of skin cancer was also BMI-independent.

Lung cancer is strongly associated with smoking, the leading risk factor for the global burden of cancer31. We observed that the effect of AI-IR on the incidence of bronchial and lung cancer is significant even when we adjusted also for smoking status (never smoker, previous smoker, and current smoker); The same is true for the incidence of the composite cancers (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). We also looked at a possible joint effect of AI-IR and smoking status on the incidence of bronchial and lung cancer (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In the never smoker group, HRs adjusted for age, sex, and BMI were not significantly different (P = 0.513) between the AI-IR positive group (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.85–1.37) and the AI-IR negative group. In the current smoker group, HRs adjusted for the three factors were also not significantly different (P = 0.726) between the AI-IR positive group (HR, 17.42; 95% CI, 14.66–20.71) and the AI-IR negative group (HR, 17.89; 95% CI, 15.63–20.47). On the other hand, in the previous smoker group, HRs adjusted for the three factors in the AI-IR positive group (HR, 5.52; 95% CI, 4.69–6.49) was significantly higher than that in the AI-IR negative group (HR, 3.84; 95% CI, 3.35–4.40), when examined by post-hoc analysis (P = 7.78 × 10−8, Supplementary Fig. 5c). We observed similar interaction effect on the incidence of the composite cancers; predicted insulin resistance increased the incidence in the never smoker group and the previous smoker group, but not in the current smoker group (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Notably, the composite cancers include esophagus, pancreas, stomach, liver, and bronchial and lung cancers, all of which are known to have increased risk due to smoking32. These results suggest that the effect of AI-IR on the incidence of bronchial and lung cancer or the composite cancers is the most tangible in the previous smoker group; however, the effect may have been masked in the current smoker groups because the absolute risks of the incidence are overwhelmingly high.

Machine learning-predicted insulin resistance enables improved cancer risk stratification compared to previously reported metrics

Finally, to examine whether AI-IR provides a better prediction of the composite cancer incidence than previously established metrics such as BMI, MetS, TG/HDL ratio, and TyG index, we classified participants who were free of diabetes and cancer at baseline into four groups according to their AI-IR status (positive or negative) and the status of these metrics (positive or negative). When we consider AI-IR and BMI, we observed that the incidence of the composite cancers was significantly higher (P = 2.28 × 10−2) for the AI-IR single-positive group (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.11–1.26; P < 9.5 × 10−8) compared with the BMI single-positive group (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.95–1.15; P = 0.38). BMI of 30 or higher alone did not significantly increase the composite cancer incidence when individuals were negative for AI-IR. We also observed that the incidence of the composite cancers was significantly higher (P = 2.01 × 10−5) in the AI-IR and BMI double-positive group (HR, 1.30; 95% CI 1.24–1.37; P < 1 × 10−11) compared with the BMI single positive group, underscoring that AI-IR provides substantially improved cancer risk stratification among individuals with obesity (Fig. 5a). When considering AI-IR (positive or negative) and MetS (positive or negative), the AI-IR single positive group (HR, 1.21; 95% CI 1.12–1.31; P = 2.1 × 10−6) and the MetS single positive group (HR, 1.19; 95% CI 1.12–1.26; P = 1.8 × 10−9) exhibited comparable HRs (P = 0.649) for the incidence of the composite cancers. However, the incidence of composite cancers was significantly higher (P = 1.49 × 10⁻⁴) in the AI-IR and MetS double-positive group (HR, 1.34; 95% CI 1.27–1.40; P < 1 × 10⁻¹¹) compared with the MetS single-positive group (Fig. 5b). Similar patterns were observed when we consider AI-IR and TG/HDL ratio (Fig. 5c). When considering AI-IR and TyG index, the incidence of the composite cancers was significantly higher (P = 1.92 × 10−2) for the AI-IR single-positive group (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.13–1.35; P = 7.2 × 10−6) compared with the TyG single-positive group (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05–1.16; P = 1.1 × 10−4). We also observed that the incidence of the composite cancers was significantly higher (P < 1 × 10−11) for the AI-IR and TyG double-positive group (HR, 1.32; 95% CI 1.26–1.39; P < 1 × 10−11) compared to the TyG single-positive group (Fig. 5d). Altogether, these results indicate that AI-IR enables improved cancer risk stratification compared to previously established metrics.

Effect of AI-IR and BMI (a), Metabolic syndrome (MetS) (b), TG/HDL ratio (c), or TyG index (d) on the hazard ratio (HR) for incidence of the composite cancer during the follow-up period in participants without diabetes at baseline. Cox proportional hazards model was used with a two-sided Wald test. In the graph, points represent the estimated OR, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Discussion

Here, we examined the effect of insulin resistance on cancer incidence at the population scale by applying a machine learning-based prediction model of insulin resistance, AI-IR, with nine clinical parameters in the UK Biobank. As a foundation for our investigation, we compared AI-IR with previously established simpler metrics of obesity (BMI), metabolic syndrome (MetS), and insulin resistance (TG/HDL ratio and TyG index) and demonstrated that AI-IR exhibits the highest predictive capability for the incidence of diabetes. We acknowledge that BMI is the most influential single parameter for AI-IR23. When we categorized individuals into four groups based on AI-IR status (positive or negative) and BMI (≥30 or <30) (Fig. 2b), BMI may contribute to diabetes risk in a manner that partially overlaps with AI-IR. Nevertheless, AI-IR significantly outperformed BMI and other metrics in predicting diabetes incidence, consistent with the notion that AI-IR captures multidimensional clinical and biochemical abnormalities beyond BMI alone.

We observed that AI-IR was significantly associated with a higher incidence of uterine, kidney, esophagus, pancreas, colon, and breast cancer, after Bonferroni correction. AI-IR was nominally associated with a higher incidence of renal pelvis, small intestine, stomach, liver and gallbladder, leukemia, and bronchial and lung cancer. Among the above-mentioned cancer types, a large-scale meta-analysis of observational studies found that incidences of uterine (in females), kidney, esophagus, pancreas (in females), colon, leukemia, and breast (in females) cancer were positively associated with BMI6. Furthermore, a Mendelian randomization study using the UK Biobank also found that incidences of uterine, esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, and lung cancer were positively associated with BMI7. Relatively consistent effects of predicted insulin resistance and BMI on the incidences of several types of cancer can be expected because in our prediction model, BMI has the highest feature importance among the nine parameters23. In line with our observations, a Mendelian randomization using 18 variants associated with fasting insulin levels found that genetically predicted higher fasting insulin levels increased the risk of kidney, pancreas, and lung cancer4. Similar Mendelian randomization studies have been replicated and summarized elsewhere33. In the present study, we observed that the incidence of skin cancer was negatively associated with predicted insulin resistance. Consistently, observational studies found that the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer, which accounts for 95% of all skin cancer, is inversely correlated with BMI34,35.

We observed a BMI-independent association between AI-IR and a higher incidence of bronchial and lung cancer, even after Bonferroni correction. Intriguingly, in contrast to Mendelian randomization studies, multiple observational studies reported an association between higher BMI and lower incidence of lung cancer6,36. The observed association is suggested to be influenced, at least partly, by the effect of smoking on increasing the risk of lung cancer while reducing body weight37,38. Considering that the feature importance of our model was highest for higher BMI, followed by higher FPG, lower HDL, and higher TG23, the effect of AI-IR on bronchial and lung cancer is BMI-independent, but it may be dependent on FPG, HDL, and TG. Supportively, studies reported that both high TG and low HDL are positively associated with lung cancer risk39,40. Our work sheds insight into the BMI-independent effect of insulin resistance on bronchial and lung cancer, the risk of which is strongly associated with smoking. Smoking itself is reported to cause insulin resistance41,42, possibly via its pro-inflammatory effect43,44.

We acknowledge that the BMI-independent effect of insulin resistance on increased cancer risk has been previously reported. While the definitions of MetS, TG/HDL ratio, and TyG index do not include BMI, MetS—originally developed as an indicator of visceral adiposity—has been reported as a risk factor for certain types of cancer12,13,14,15,16,17. Indeed, we observed that higher BMI (≥30) alone was not associated with an increased risk of composite cancer (Fig. 5a). AI-IR was a better predictor of composite cancer compared to BMI and TyG index (Fig. 5a, d), but its predictive capability was comparable to that of MetS and TG/HDL ratio (Fig. 5b, c). Having said that, since AI-IR demonstrated the highest predictive capability for the incidence of diabetes among the examined metrics, including MetS and TG/HDL ratio (Fig. 2), and diabetes itself is a significant risk factor for the composite cancers (Fig. 4a), we argue that AI-IR is a robust and clinically relevant metric for predicting both diabetes and composite cancer incidence. Furthermore, AI-IR captures both BMI-dependent and BMI-independent effects of insulin resistance.

A key strength of our study is that it leverages a machine learning-based prediction model of insulin resistance to look at the effect of insulin resistance on the incidence of cancer at the population scale. Using nine routinely measured clinical parameters, AI-IR outperforms previously established simpler metrics—including BMI, MetS, TG/HDL ratio, and TyG index—in predicting both diabetes and composite cancer incidence. Our model provides “digital biomarker of insulin resistance” that merges all parameters currently established as components of insulin resistance into a single metric, which will be utilized for the identification of high-risk individuals and focused screening of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Individuals identified as AI-IR positive could undergo earlier or more frequent monitoring of glucose metabolism, cardiovascular risk factors, and age-appropriate cancer screening, thereby improving opportunities for early detection and intervention. Nevertheless, our study also has some limitations. First, the participants of UK Biobank were aged 40–69 years at recruitment and were mainly of European ancestry. Future studies are needed to evaluate the effect of AI-IR on cancer incidence in a more diverse cohort with respect to age and ancestry, to establish its utility for improved risk stratification in the broader population. Second, while the current study demonstrated that our model outperforms previously established metrics, further efforts would be warranted to improve the model in terms of both predictive capability and simplicity. Third, the mechanistic link between insulin resistance and cancer remained elusive in the current study. However, leveraging AI-IR could provide deeper insights into the pathophysiology of insulin resistance, for example, by enabling genome-wide association studies on insulin resistance itself, rather than relying on BMI (a surrogate marker of insulin resistance) or type 2 diabetes (a consequence of insulin resistance alongside impaired insulin secretion).

In conclusion, here we showed that machine learning-predicted insulin resistance is a risk factor for diabetes and composite cancers. Our model exhibited the highest predictive capability for the incidence of diabetes and composite cancers among the examined metrics, highlighting the potential of a machine learning-assisted approach to enhance clinical practice and gain insights into disease pathophysiology.

Methods

The UK Biobank

The present study has been approved by the UK Biobank (approved research ID 78912), which in turn was approved by the National Health Service (NHS) North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee. The UK Biobank is a prospective cohort of individuals aged 40–69 years at recruitment between 2006 and 201045. All participants provided written informed consent. At baseline, participants completed lifestyle and health-related questionnaires, interviews, and physical measurements. Genotype and biomarker data were also collected, and health-related outcomes were obtained via linkage to NHS medical records.

Machine learning-based prediction model of insulin resistance (AI-IR)

Previously, we developed and validated a machine learning-based prediction model of insulin resistance23. Briefly, an XGboost model was trained to predict the probability that HOMA-IR exceeds 2.5 in non-diabetic populations, by considering nine clinical parameters (age, sex, race, BMI, FPG, glycohemoglobin, TG, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol). Participants were classified as AI-IR positive if the predicted probability was greater than 0.5. The model achieved an area under the curve of 0.88.

Ascertainment of disease prevalence and incidence

The primary outcomes of the current work were the incidence of overall and site-specific cancers in participants without a history of cancer at enrollment. Cancer incidence was defined as the first diagnosis after enrollment, with cancer type (ICD-10) and date obtained from UK Biobank Data-Fields 40005 and 40006. Follow-up was conducted until the last available date in the registries: 31 December 2020 for England, 30 November 2021 for Scotland, and 31 December 2016 for Wales. Participants without cancer were censored at the last available date of the respective registry, ensuring consistent follow-up for all participants. For participants recorded in the combined “Originating from England/Wales (E/W)” registry, it was not possible to assign registry-specific censor dates to each participant. In these cases, censor dates were assigned as 31 December 2016 for participants born in Wales (determined by Data-Fields 1647 and 20115), and 31 December 2020 for all others.

AI-IR status was defined using nine parameters obtained at enrollment. Race, as implemented in the AI-IR model, was derived from self-reported race (UK Biobank Data-Field 21000) collected at baseline. This variable was included as a demographic input to account for population-level differences in clinical measurements and healthcare context, and was not intended to represent genetic ancestry or biological determinants. Diabetes status was defined using observed phenotypes. Participants with HbA1c > 6.5% at enrollment and/or self-report of a physician’s diagnosis were classified as having diabetes. For short-term follow-up analysis in the UK Biobank, new-onset of diabetes was defined using follow-up HbA1c and/or self-report of physician’s diagnosis, while long-term follow-up relied on NHS-recorded diagnosis (ICD-10 E08, 09, 11, and 13), with diagnosis date defined as the date of admission with diabetes. All participants with diabetes were included in these analyses.

Incidences of 3-point major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE; a composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke) and 4-point MACE (3-point MACE plus heart failure requiring hospitalization), overall mortality, and cardiovascular mortality were also evaluated. We used algorithmically-defined outcomes (Category 42), which were derived from baseline assessment, hospital admissions, and death registries. Non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke were defined using Data-Fields 42000 and 42006, respectively. Heart failure requiring hospitalization was obtained from hospital episode statistics (Resource 138483; ICD-10 I50.9), and mortality data were obtained from Data-Field 40001, collected until 30 November 2022. Smoking status was defined using Data field 20116.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as number (percentage). Differences across groups were assessed using independent t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorial variables. Sex was determined through the clinical record (UK Biobank Data-Field 31) and confirmed by genetics. Sex was used as a covariate in the analyses.

To evaluate the effect of AI-IR on incident diabetes, logistic regression was performed among participants without diabetes at baseline. Cox regression was not used because exact onset times were unavailable; instead, the duration from baseline to follow-up was included as a covariate. For stratified analyses based on fasting duration prior to blood collection, fasting time was obtained from Data-Field 74. Predictive performance of AI-IR and previously reported metrics was compared using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Joint effects of AI-IR and previously reported metrics on diabetes incidence were also examined. Cut-offs were defined as BMI of 30, TG/HDL ratio of 3.025, and TyG index of 4.6827, based on previous literatures. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was defined as the presence of at least three of the following: (1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥ 102 cm in male or ≥ 88 cm in female), (2) elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL), (3) reduced HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL in male or <50 mg/dL in female), (4) elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mmHg), and (5) elevated fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dL). Use of medications for triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, blood pressure, or glucose was not considered, as medication use was not included in the computation of AI-IR.

To evaluate the effect of AI-IR or diabetes on the cumulative incidence of 3- and 4-point MACE, overall and cardiovascular mortality, and overall and site-specific cancers, Kaplan–Meier curves were used to compare time to diagnosis across groups, and Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratio (HRs). Models were conducted as crude (unadjusted), adjusted for age and sex, or adjusted for age, sex, and BMI, to account for potential confounding. Age and BMI were treated as continuous variables; sex was binary. To further account for the effect of age on cancer incidence, we also conducted analyses with age as the underlying time variable. This approach ensures that each participant contributes person-time from their age at enrollment until their age at censoring or event, providing a more effective control for confounding by age than including age as a covariate. Joint and interaction effects between AI-IR and smoking status were also evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models, including main effects and an interaction term between AI-IR status and smoking status46,47. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4, and a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study were derived from the UK Biobank resource. Individual-level data cannot be publicly shared, but the UK Biobank resource is available to bona fide researchers for health-related research in the public interest upon registration (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). The current study was conducted under UK Biobank approved research ID 78912. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for computing AI-IR from the nine input parameters is covered by filed patent applications (application numbers: 113111331 in Taiwan, 2024-056758 in Japan, and 18/616,217 in the United States) and cannot be publicly available. A compiled standalone software for AI-IR calculation was made available to editors and peer reviewers at the time of submission for evaluation purposes. To ensure transparency while respecting our patent restrictions, we created a website on a public cloud server that allows users to calculate AI-IR based on the nine input parameters (https://ai-ir.com.tw). Registration of a username and email address is required to obtain access.

References

Petersen, M. C. & Shulman, G. I. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev. 98, 2133–2223 (2018).

Gast, K. B., Tjeerdema, N., Stijnen, T., Smit, J. W. A. & Dekkers, O. M. Insulin resistance and risk of incident cardiovascular events in adults without diabetes: meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7, e52036 (2012).

Ling, S. et al. Association of type 2 diabetes with cancer: a meta-analysis with bias analysis for unmeasured confounding in 151 cohorts comprising 32 million people. Diab. Care 43, 2313–2322 (2020).

Yuan, S. et al. Is type 2 diabetes causally associated with cancer risk? Evidence from a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Diabetes 69, 1588–1596 (2020).

Tsilidis, K. K., Kasimis, J. C., Lopez, D. S., Ntzani, E. E. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ 350, g7607–g7607 (2015).

Renehan, A. G., Tyson, M., Egger, M., Heller, R. F. & Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371, 569–578 (2008).

Vithayathil, M. et al. Body size and composition and risk of site-specific cancers in the UK Biobank and large international consortia: a mendelian randomisation study. PLoS Med. 18, e1003706 (2021).

Lauby-Secretan, B. et al. Body fatness and cancer-viewpoint of the IARC working group. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 794–798 (2016).

Gallagher, E. J. & LeRoith, D. Hyperinsulinaemia in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 629–644 (2020).

Greten, F. R. & Grivennikov, S. I. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 51, 27–41 (2019).

Alberti, K. G. M. M. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645 (2009).

Winn, M. et al. Metabolic dysfunction and obesity-related cancer: results from the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cancer Med. 12, 606–618 (2023).

Deng, L. et al. The association of metabolic syndrome score trajectory patterns with risk of all cancer types. Cancer 130, 2150–2159 (2024).

Pothiwala, P., Jain, S. K. & Yaturu, S. Metabolic syndrome and cancer. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 7, 279–288 (2009).

Jinjuvadia, R., Patel, S. & Liangpunsakul, S. The association between metabolic syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma: systemic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 48, 172–177 (2014).

Esposito, K., Chiodini, P., Colao, A., Lenzi, A. & Giugliano, D. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diab. Care 35, 2402–2411 (2012).

Esposito, K. et al. Metabolic syndrome and endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocrine 45, 28–36 (2014).

Gunter, M. J. et al. A prospective evaluation of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I as risk factors for endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 17, 921–929 (2008).

Gunter, M. J. et al. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, endogenous estradiol, and risk of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Res. 68, 329–337 (2008).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Bonora, E. et al. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diab. Care 23, 57–63 (2000).

Stühlinger, M. C. et al. Relationship between insulin resistance and an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. JAMA 287, 1420–1426 (2002).

Tsai, S.-F., Yang, C.-T., Liu, W.-J. & Lee, C.-L. Development and validation of an insulin resistance model for a population without diabetes mellitus and its clinical implication: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 58, 101934 (2023).

Oliveri, A. et al. Comprehensive genetic study of the insulin resistance marker TG:HDL-C in the UK Biobank. Nat. Genet. 56, 212–221 (2024).

McLaughlin, T. et al. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann. Intern. Med. 139, 802–809 (2003).

Lopez-Jaramillo, P. et al. Association of the triglyceride glucose index as a measure of insulin resistance with mortality and cardiovascular disease in populations from five continents (PURE study): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4, e23–e33 (2023).

Sánchez-García, A. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the triglyceride and glucose index for insulin resistance: a systematic review. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 4678526 (2020).

Simental-Mendía, L. E., Rodríguez-Morán, M. & Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6, 299–304 (2008).

White, M. C. et al. Age and cancer risk. Am. J. Prev. Med. 46, S7–S15 (2014).

Laconi, E., Marongiu, F. & DeGregori, J. Cancer as a disease of old age: changing mutational and microenvironmental landscapes. Br. J. Cancer 122, 943–952 (2020).

Tran, K. B. et al. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010–19: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 400, 563–591 (2022).

Weber, M. F. et al. Cancer incidence and cancer death in relation to tobacco smoking in a population-based Australian cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 149, 1076–1088 (2021).

Pearson-Stuttard, J. et al. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: an umbrella review of observational and mendelian randomization studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 30, 1218–1228 (2021).

Pothiawala, S., Qureshi, A. A., Li, Y. & Han, J. Obesity and the incidence of skin cancer in US Caucasians. Cancer Causes Control 23, 717–726 (2012).

Tang, J. Y. et al. Lower skin cancer risk in women with higher body mass index: the Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 22, 2412–2415 (2013).

Bhaskaran, K. et al. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. Lancet 384, 755–765 (2014).

Yu, D. et al. Overall and central obesity and risk of lung cancer: a pooled analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, 831–842 (2018).

Zhou, W. et al. Causal relationships between body mass index, smoking and lung cancer: univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization. Int. J. Cancer 148, 1077–1086 (2021).

Lin, X. et al. Blood lipids profile and lung cancer risk in a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Clin. Lipido. 11, 1073–1081 (2017).

Ulmer, H. et al. Serum triglyceride concentrations and cancer risk in a large cohort study in Austria. Br. J. Cancer 101, 1202–1206 (2009).

Facchini, F. S., Hollenbeck, C. B., Jeppesen, J., Chen, Y. D. & Reaven, G. M. Insulin resistance and cigarette smoking. Lancet 339, 1128–1130 (1992).

Chiolero, A., Faeh, D., Paccaud, F. & Cornuz, J. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 801–809 (2008).

Fröhlich, M. et al. Independent association of various smoking characteristics with markers of systemic inflammation in men. Results from a representative sample of the general population (MONICA Augsburg Survey 1994/95). Eur. Heart J. 24, 1365–1372 (2003).

Lee, J., Taneja, V. & Vassallo, R. Cigarette smoking and inflammation: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Dent. Res. 91, 142–149 (2012).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Hiraike, Y., Yang, C. T., Liu, W. J., Yamada, T. & Lee, C. L. FTO obesity variant-exercise interaction on changes in body weight and BMI: the Taiwan Biobank Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, E3673–E3681 (2021).

Lee, C.-L. et al. Interaction between type 2 diabetes polygenic risk and physical activity on cardiovascular outcomes. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 31, 1277–1285 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the UK Biobank for their dedication and contributions. This work was funded by a research grant from the University of Tokyo Excellent Young Researcher Program to Y.H.; by Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Fusion Oriented Research for disruptive Science and Technology (FOREST) Program, grant number JPMJFR245I to Y.H.; by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), grant number 24ek0210204h0001 to Y.H.; by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists, grant numbers 19K17976 and 23K15387 to Y.H.; by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory), grant number 25K22704 to Y.H.; by a grant for Front Runner of Future Diabetes Research from the Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology, grant number 17F005 to Y.H.; by a grant from MSD Life Science Foundation to Y.H.; by a Life Science Research grant and a Life Science Research Continuous grant from Takeda Science Foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from Public Health Research Foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from Mishima Kaiun Memorial Foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from Japan Health Foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from Kao Research Council for the Study of Healthcare Science to Y.H.; by a grant from TANITA Healthy Weight Community Trust to Y.H.; by a grant from Senri Life Science Foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from Inamori Foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from the Mitsubishi foundation to Y.H.; by a grant from Japanese Biochemical Society to Y.H.; by a grant from Lotte foundation to Y.H.; by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists, grant number 19K19432 to T.Yamada; by a JSPS KAKENHI Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (A), grant number 21KK0293 to T.Yamada; by a grant from The Vehicle Racing Commemorative Foundation to K.H.; by a grant from Taichung Veterans General Hospital, grant numbers TCVGH-1137313C, TCVGH-1137306D, TCVGH-1144302C, TCVGH-1144302D, TCVGH-VTA114V211, and TCVGH-PNTHU1145001 to CL.L.; by a grant from the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan, grant number 113-2314-B-075A-003 and 114-2314-B-075A-011-MY3 to CL.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and CL.L. designed the study. CL.L. and WJ.L. conducted the formal statistical analysis. Y.H., T.Yamada, CL.L., WJ.L., K.H., T.Yamauchi, and S.Y. contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y.H. wrote the manuscript with inputs from CL.L. and all other authors. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CL.L. and WJ.L. are inventors of a filed patent application related to this work, entitled “SYSTEM AND METHOD FOR PREDICTING INSULIN RESISTANCE OR PANCREATIC BETA-CELL FUNCTION AND COMPUTER READABLE MEDIUM THEREOF” (application numbers: 113111331 in Taiwan, 2024-056758 in Japan, and 18/616,217 in the United States). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Emily Gallagher who co-reviewed with Hassal Lee, Manik Garg and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CL., Yamada, T., Liu, WJ. et al. Machine learning-predicted insulin resistance is a risk factor for 12 types of cancer. Nat Commun 17, 1396 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68355-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68355-x