Abstract

Quantum resources enable us to achieve an exponential advantage in learning the properties of unknown physical systems by employing quantum memory. While entanglement with quantum memory is recognized as a necessary qualitative resource, its quantitative role remains less understood. In this work, we distinguish between two fundamental resources provided by quantum memory—entanglement and ancilla qubits—and analyze their separate contributions to the sampling complexity of quantum learning. Focusing on the task of Pauli channel learning, a prototypical example of quantum channel learning, remarkably, we prove that vanishingly small entanglement in the input state already suffices to accomplish the learning task with only a polynomial number of channel queries in the number of qubits. In contrast, we show that without a sufficient number of ancilla qubits, even learning partial information about the channel demands an exponentially large sample complexity. Thus, our findings reveal that while a large amount of entanglement is not necessary, the dimension of the quantum memory is a crucial resource. Hence, by identifying how the two resources contribute differently, our work offers deeper insight into the nature of the quantum learning advantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum advantage arises from the utilization of quantum effects, manifesting in diverse tasks such as accelerating computation by quantum computing1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, and improving sensitivity by quantum metrology12,13,14,15. In addition to the above, a particularly promising approach to realize a quantum advantage, recently attracting much attention, is quantum learning, which leverages quantum effects to achieve high efficiency in learning unknown physical systems that classical approaches cannot achieve from an information perspective16,17. Various forms of quantum learning advantage have been investigated, including expectation value estimation16,17, learning quantum channels18,19,20,21,22,23, and extension of learning techniques to continuous-variable systems for the characterization of quantum states24 and channels25. Especially, quantum channel learning has attracted increasing attention due to its utility in learning errors of quantum devices26,27 and mitigating noise28,29,30 for quantum computing.

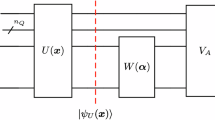

The quantum advantage in channel learning is often defined by the accessibility to quantum memory16,17; thus, quantum memory is regarded as a quantum resource in this context. Hence, two different families of learning schemes are considered and compared with each other20,22,24,25, which are illustrated in Fig. 1. As depicted in Fig. 1(a), learning an unknown n-qubit quantum channel Λ involves preparing input states, applying Λ, and estimating its parameters from measurement outcomes16. Without quantum memory, the required sample complexity for learning—the number of channel applications—often scales exponentially with n18,20,21,22,23. In contrast, by using quantum memory [Fig. 1(b)], the sample complexity can be significantly reduced. As an example, Pauli channel learning, which is a crucial task for various applications26,27,28,29,30, can be accomplished with only O(n) samples by employing a 2n-qubit Bell pair as input, while any scheme in Fig. 1(a) requires Ω(2n) samples21,23, establishing exponential quantum advantage through quantum memory. In addition, this advantage has recently been demonstrated experimentally31,32.

a Learning a quantum channel acting on an n-qubit system without quantum memory. b Quantum channel learning with the assistance of quantum memory. The availability of quantum memory allows the use of k ancilla qubits as a resource. Another resource, the entanglement entropy between the ancilla and the system, is denoted by Sa∣s. The channel acts only on the system, while the ancilla is stored in the quantum memory. Joint measurements, such as Bell measurements, are also permitted.

Accordingly, quantum memory has been identified as a key resource in quantum learning. In fact, in the literature, entanglement-enabled learning and ancilla-assisted learning are used interchangeably in this context20,22,24,25, which implicitly treats the two resources as equivalent. From an information-theoretic perspective, however, two distinct types of resources emerge when quantum memory is provided: the ancilla qubits in the memory and the entanglement between these ancilla qubits and the system. In many cases, these two resources can be regarded as effectively identical, such as when Bell pairs are used as input probes. However, this equivalence does not necessarily hold in general, and understanding its breakdown is the main focus of this work.

In this work, we consider Pauli channel learning and show that the two resources, ancilla qubits and entanglement between the ancilla and the system, contribute in fundamentally distinct ways to the exponential quantum advantage. In particular, we first prove that while the sample complexity must be exponential when the number of ancilla qubits is limited20,21,23, even with a vanishingly small amount of entanglement, a polynomial number of samples is sufficient to learn a Pauli channel. This highlights that a large amount of entanglement is not necessary for the exponential quantum advantage as long as the number of ancilla qubits is sufficient. To understand the necessary number of ancilla qubits in practice, we consider learning a subset of the channel parameters—specifically, the Pauli eigenvalues associated with low-weight Pauli strings (see Definition 1). We then prove that even in this easier setting, if the number of ancilla qubits is limited, the sample complexity must be exponential. This result emphasizes that the number of ancilla qubits plays an even more crucial role than previously recognized. Therefore, by revealing the distinct contributions of entanglement and ancilla qubit number to the exponential quantum learning advantage, our work provides a comprehensive connection between quantum resources and the sample complexity of channel learning.

Results

Pauli channel learning setup

We begin by introducing the definitions of Pauli strings, Pauli channels, and Pauli channel learning, which are the main subject of this work. Each Pauli operator Pa ∈ {I, X, Y, Z } is labeled by a 2-bit string \(a:={a}_{x}{a}_{z}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2}\), and expressed as \({P}_{a}={i}^{{a}_{x}{a}_{z}}{X}^{{a}_{x}}{Z}^{{a}_{z}}\). This extends to an n-qubit system via the Pauli string \({P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}{=\bigotimes }_{j=1}^{n}{P}_{{a}_{j}}\) determined by a 2n-bit string \({{{\bf{a}}}}:={a}_{1}{a}_{2}\cdots {a}_{n}={a}_{1,x}{a}_{1,z}{a}_{2,x}{a}_{2,z}\cdots {a}_{n,x}{a}_{n,z}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}\). Any Pa and Pb satisfy PaPb = (−1)〈a, b〉PbPa, where \(\langle {{{\bf{a}}}},{{{\bf{b}}}}\rangle :={\sum }_{j=1}^{n}({a}_{j,x}{b}_{j,z}+{a}_{j,z}{b}_{j,x})\,{{{\rm{mod}}}}\,\,2\). The Pauli weight ∣a∣ is defined as the number of non-identity operators in the Pauli string Pa. A Pauli channel Λ( ⋅ ) is defined as

where p(a) is a Pauli error rate, and λ(b) is a Pauli eigenvalue. They are related via the Walsh-Hadamard transform, given by \(p({{{\bf{a}}}})=\frac{1}{{4}^{n}}{\sum }_{{{{\bf{b}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}}\lambda ({{{\bf{b}}}}){(-1)}^{\langle {{{\bf{a}}}},{{{\bf{b}}}}\rangle }\)18.

As shown in Fig. 1(b), we treat the ancilla as an additional register consisting of k qubits. Since the channel acts only on the system, the output state corresponding to an input state ρin is given by \(({{\mathbb{1}}}_{{{{\rm{anc}}}}}\otimes {{{\boldsymbol{\Lambda }}}})({\rho }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}})=\frac{1}{{2}^{n}}{\sum }_{{{{\bf{b}}}}}\lambda ({{{\bf{b}}}}){{{{\rm{Tr}}}}}_{{{{\rm{sys}}}}}[({I}_{{{{\rm{anc}}}}}\otimes {P}_{{{{\bf{b}}}}}){\rho }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}]\otimes {P}_{{{{\bf{b}}}}}\), where \({{\mathbb{1}}}_{{{{\rm{anc}}}}}\) and Ianc denote the identity channel and operator on the ancilla, respectively, and Trsys denotes the partial trace over the system.

Based on the definition of the Pauli channel in Eq. (1), we define the Pauli channel learning task.

Definition 1

((ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning task) We are given access to N copies of the Pauli channel Λ. Classical data are collected by preparing an input state, applying a single copy of the channel, and measuring the output. In each round, both the input and measurement POVM can be chosen adaptively based on prior measurement outcomes. After N measurements, the goal is to provide an estimate \(\widehat{\lambda }({{{\bf{b}}}})\) satisfying \(| \widehat{\lambda }({{{\bf{b}}}})-\lambda ({{{\bf{b}}}})| \le \varepsilon\) for any \({{{\bf{b}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}\) such that ∣b∣≤w with success probability at least 1 − δ.

In this setting, the number of channel queries required to accomplish the task, denoted by N, is referred to as the sample complexity. The motivation for estimating λ(b) for low ∣b∣ stems from realistic physical error models18. The number of parameters to learn is determined by the maximum weight w; when w = n, the learning task requires estimating a total of 4n parameters. We consider only 0≤k≤n, since k = n ancilla qubits are sufficient to accomplish the task with N = O(n) even when w = n21. In addition, as implied in the definition, this work focuses on non-concatenated applications of the channel, although concatenated applications might potentially reduce the sample complexity23, which we leave as future work.

Learning with restricted entanglement

We first analyze the sample complexity in Pauli channel learning depending on the entanglement between the system and the ancilla. Here, the entanglement is defined as the entanglement entropy of the input probe state, and we denote it as Sa∣s [Fig. 1(b)]. As highlighted in several previous works16,20,21,22,23, if Sa∣s = 0, an exponentially large N is required to accomplish the (ε, δ, w = n)-Pauli channel learning task. Consequently, one might expect that even if enough k = n ancilla qubits are available, the exponential N may still be necessary when the input state has small Sa∣s, i.e., it is close to a separable state. Remarkably, our first main result shows that the exponential advantage can be achieved using only small Sa∣s, even for estimating all λ(b), i.e., w = n. More precisely, our theorem below reveals that even when Sa∣s in the input state is inverse-polynomially small, the Pauli channel can be learned with polynomially many samples in n.

Theorem 1

For an n-qubit system with k = n ancilla qubits, there exists a scheme that accomplishes the (ε, δ, n)-Pauli channel learning task with sample complexity \(N=O(n{\alpha }^{-2}\times {\varepsilon }^{-2}\log {\delta }^{-1})\) by using input states, each with entanglement Sa∣s = Θ(nα), where α = Θ(1/poly(n)).

Hence, Theorem 1 implies that the exponential advantage remains attainable even when highly entangled states are inaccessible. This reveals that the contributions of entanglement and ancilla qubit number to the exponential advantage are fundamentally distinct, which becomes evident by comparing the two cases: (1) If only k ancilla qubits are allowed, even if maximally entangled states are used, i.e., Sa∣s = k, N = Ω(2(n−k)/3) is required20,21,23 (the lower bound will be improved later). (2) In contrast, when n ancilla qubits are provided, by preparing input states such that each has the same amount of entanglement Sa∣s = k (i.e., setting α = k/n), the learning task can be accomplished with a sample complexity that scales polynomially with n.

Note that a smaller Sa∣s leads to a larger N as a trade-off. Thus, the total entanglement resource of the N copies of the input state cannot be arbitrarily reduced. For instance, when we set α = 1, each input state has entanglement Sa∣s = Θ(n), and O(n) such states are required; consequently, the total entanglement is O(n2) (this corresponds to the case where a Bell pair is employed in ref. 21). However, if we take α = 1/nc (c > 0), each input has Sa∣s = Θ(n1−c) and O(n1+2c) such states are required, so the total required entanglement is O(n2+c).

Proof Sketch. (See Supplementary Material (SM) Sec. S2 (Supplementary Material) for the full proof) To prove Theorem 1, we provide an explicit input state \(\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}(\alpha )\right\rangle\) parameterized by a constant α, with Sa∣s = Θ(nα). The input state is a superposition of the 2n-qubit Bell pair \(\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\right\rangle\) and a separable state \(\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{sep}}}}}\right\rangle\), defined as

where \(\sqrt{{\alpha }^{{\prime} }}:=\sqrt{\alpha+(1-\alpha )/{2}^{n}}-\sqrt{(1-\alpha )/{2}^{n}}\). Here, the separable state \(\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{sep}}}}}\right\rangle\) is defined as

Note that ρsep is a pure product state, and setting α = 1 recovers \(\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}(\alpha=1)\right\rangle=\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\right\rangle\). As a result of the superposition of the two states with weight α, the entanglement Sa∣s is reduced from n (of the Bell pair) to Θ(nα). For measurement, we use the Bell measurement POVM \({\{{E}_{{{{\bf{v}}}}}\}}_{{{{\bf{v}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}}\), where \({E}_{{{{\bf{v}}}}}=\frac{1}{{4}^{n}}{\sum }_{{{{\bf{a}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}}{(-1)}^{\langle {{{\bf{a}}}},{{{\bf{v}}}}\rangle }{P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\otimes {P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}\)21.

When the input state is \(\left| {\Psi }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}(\alpha )\right\rangle\) in Eq. (2) and the measurement is performed using \({\{{E}_{{{{\bf{v}}}}}\}}_{{{{\bf{v}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}}\), the probability Pr(v) of obtaining outcome v is related to the Pauli eigenvalue λ(b) as follows:

Therefore, we obtain an unbiased estimator \(\widehat{\lambda }({{{\bf{b}}}})\), which is given by \(\widehat{\lambda }({{{\bf{b}}}})=\frac{1}{N}{\sum }_{l=1}^{N}\frac{{(-1)}^{\langle {{{\bf{b}}}},{{{{\bf{v}}}}}^{(l)}\rangle }}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}({{{\bf{b}}}})}\), where \({\{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}^{(l)}\}}_{l=1}^{N}\) are the outcomes of N measurements. Applying Hoeffding’s inequality, the sample complexity N(b) sufficient to estimate a single parameter λ(b) within error ε with success probability at least 1 − δ (see Definition 1) is

From the union bound, to ensure this level of precision and confidence for any λ(b) among the 4n parameters, the sufficient sample complexity is \(N=O(n{\alpha }^{-2}\times {\varepsilon }^{-2}\log {\delta }^{-1})\).

Although our main example is the specific state given in Eq. (2), a broad class of states shares the same property: having an inverse polynomially small entanglement while enabling the learning task to be accomplished with polynomial sample complexity in n. As a generalization of the input state in Eq. (2), we find that the state \(\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}(\alpha,\varphi,{\varphi }^{*})\right\rangle :=\sqrt{{\alpha }^{{\prime} }}\left| {\varPsi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\right\rangle+\sqrt{1-\alpha }\left| \varphi \right\rangle \otimes {(\left| \varphi \right\rangle )}^{*}\), where α = Θ(1/poly(n)) and \(\left| \varphi \right\rangle\) is an arbitrary state in the n-qubit Hilbert space, retains Sa∣s = Θ(nα) and \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}({{{\bf{b}}}})=\Omega (\alpha )\) (see SM Sec. S2 D (Supplementary Material)). In addition, we show that the Werner state33 also exhibits this property (see SM Sec. S2 E (Supplementary Material)). Since it is a mixed state, we use the entanglement of formation as the entanglement measure, instead of the entanglement entropy Sa∣s34,35. Although our analysis focuses on the Bell-measurement POVM, employing more general POVMs may enable a broader set of input states to satisfy these properties.

Learning with a restricted number of ancilla qubits

In the previous section, we showed that when the system is assisted by the k = n ancilla qubits, with only limited entanglement, the full set of Pauli channel parameters can be learned within polynomial N. In contrast, if k is insufficient, it is known that an exponential N is necessary to accomplish (ε, δ, w = n)-Pauli channel learning task21,23. In the following theorem, we show that under the restriction on k, learning even a subset of the parameters (i.e., w < n) requires an exponentially large N.

Theorem 2

To accomplish the (ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning task by using k ancilla qubits, the lower bound on the required sample complexity N is

In Fig. 2, we illustrate the regime where the exponential N is required in the maximum weight-ancilla qubit number (w − k) plane, according to Eq. (6). As shown in Fig. 2, Theorem 2 highlights that a sufficient k is crucial for achieving the exponential advantage. When k is limited, even for relatively simple tasks with w < n, an exponentially large N is required regardless of the entanglement of the input state. This presents a complementary case to that in Theorem 1, which considers the situation where k is large enough but Sa∣s is limited. Therefore, we concretely establish that the two scenarios—limited k and limited Sa∣s—are essentially different in terms of their impact on the exponential learning advantage.

The regime is denoted as a function of the maximum weight w and the number of ancilla qubits k. In this figure, we focus on the case k and w scale proportionally with n. As stated in Theorem 2, the boundary of this regime is linear for w≤n/2, and becomes concave for w > n/2. According to Eq. (14), within our stabilizer-covering scheme, polynomial sample complexity is achievable only when k = n. This case is indicated by the black dashed line.

Furthermore, for the case w = n, we improve the lower bound from the previously suggested N = Ω(2(n−k)/3) in refs. 21,23 to N = Ω(2n−k). It follows from the fact that when w = n, the summation \({\sum }_{u=0}^{w}({{n}\atop{u}}){3}^{u}\) in Eq. (6) becomes 4n. In this case, since the upper bound N = O(n2n−k) is given in ref. 21, our lower bound N = Ω(2n−k) is tight up to the linear factor n.

Proof Sketch. (The detailed proof is provided in SM Sec. S3 (Supplementary Material).) To establish the lower bound on N, we introduce a hypothesis-testing game, as discussed in refs. 22,23,24,25,31. We consider two types of channels: the completely depolarizing channel Λdep and a channel with a single non-trivial eigenvalue, denoted by Λ(e, s)21. These channels are defined as

where \({{{\bf{e}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}^{2n}\) and s ∈ { − 1, 1} is a sign. For the hypothesis-testing game formulation of the particular (ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning task, we introduce the probability distribution

where 0 < x≤1 is a tunable parameter. The hypothesis-testing game is set up as follows: (1) According to Pr(e), a referee samples e and chooses the sign s uniformly at random. (2) The referee selects Λdep or Λ(e, s) with equal probability and sends N copies of the chosen channel to the player. (3) The player collects N measurement outcomes by performing one measurement on each copy. (4) Finally, the referee reveals the sampled e and asks the player to determine whether the channel is Λdep or not.

If an (ε, δ, w)-learning scheme exists, then the player can win this game with probability at least 1 − δ whenever ∣e∣≤w is sampled, by checking whether ∣λ(b)∣ < ε for any b such that ∣b∣≤w. Therefore, the player’s winning probability Pr(win) satisfies \(\Pr (\,{{{\rm{win}}}})\ge \Pr (| {{{\bf{e}}}}| \le w)\times (1-\delta )+(1-\Pr (| {{{\bf{e}}}}| \le w))\times \frac{1}{2}\), where the first term covers the case ∣e∣≤w, and the second term corresponds to the complementary case. According to Le Cam’s two-point method36, the total variation difference (TVD) provides an upper bound on Pr(win), where the TVD quantifies the difference between the output distributions of Λdep and Λ(e, s). The bound is given by \(\frac{1}{2}(1+\,{{{\rm{TVD}}}})\ge \Pr ({{{\rm{win}}}})\), and as a result, we have

where \(\Pr (| {{{\bf{e}}}}| \le w)=\frac{1}{{(1+3x)}^{n}}{\sum }_{u=0}^{w}({{n}\atop{u}}){(3x)}^{u}\). From Eq. (9), the lower bound on N can be derived by finding an upper bound on the TVD as a function of N, k, n, w, and x. Our key improvement in the proof technique is introducing the probability distribution in Eq. (8). Since Eq. (9) holds for any Pr(e), we can choose the value of x that maximizes the resulting lower bound on N. Using the optimal choice of x, we derive Eq. (6).

We find that the lower bound in Theorem 2 is not tight, and resolving a specific technical step would enable its improvement. In SM Sec. S3 E (Supplementary Material), we present a detailed formulation of the lower bound we expect to be achievable. If the expectation outlined in SM holds, then the parameter k plays an even more critical role: when k and w scale proportionally with n, an exponential number of channel queries is required whenever k < n, irrespective of the value of w; in other words, the boundary shown in Fig. 2 converges to k/n = 1.

To more precisely characterize the role of the number of ancilla qubits in the (ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning, we further investigate an upper bound on the sample complexity N. In particular, through the derivation of the upper bound in Theorem 3, we show that the lower bound in Eq. (6) is tight when k = 0, up to a small polynomial.

Theorem 3

When k = 0, the upper bound on N to accomplish the (ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning task is

When k = 0, the lower bound in Eq. (6) matches the upper bound in Eq. (10) up to a polynomial factor of n. Theorem 3 implies that when \(w=\Theta (\log (n))\), although the number of parameters to be learned scales quasi-polynomially, the sample complexity grows only polynomially. Additionally, by combining with the lower bound in Theorem 2, we reveal that the scaling of the sample complexity exhibits a transition at the threshold w = n/2. We prove the theorem by explicitly constructing the learning scheme using the concept of the stabilizer covering.

Proof Sketch. (Further details can be found in SM Sec. S4 (Supplementary Material).) To derive the upper bound on the sample complexity, we employ the concept of the stabilizer covering18. Given a set of Pauli strings \({\mathsf{P}}\), a set \({\mathsf{C}}={\{{{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\}}_{i}\) of stabilizer groups \({{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\) is called a stabilizer covering of \({\mathsf{P}}\) if it satisfies \({\mathsf{P}}\subseteq {\bigcup }_{{{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\in {\mathsf{C}}}{{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\). A stabilizer covering of \({\mathsf{P}}\) is not unique, and we denote by \({{{\rm{CN}}}}({\mathsf{P}})\) the minimal size \(| {\mathsf{C}}|\) among all stabilizer coverings of \({\mathsf{P}}\).

For the task of learning all λ(b) such that \({P}_{{{{\bf{b}}}}}\in {\mathsf{P}}\), the stabilizer covering provides an upper bound on N as21

The proof is as follows: given a stabilizer group \({{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\), all λ(b) such that \({P}_{{{{\bf{b}}}}}\in {{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\) can be estimated by using only \(N=O(n\times {\varepsilon }^{-2}\log {\delta }^{-1})\) samples. Accordingly, for a stabilizer covering \({\mathsf{C}}\) of \({\mathsf{P}}\) satisfying \(| {\mathsf{C}}|={{{\rm{CN}}}}({\mathsf{P}})\), repeating the above estimation for each \({{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\in {\mathsf{C}}\) enables us to estimate all λ(b) such that \({P}_{{{{\bf{b}}}}}\in {\mathsf{P}}\), since every element in \({\mathsf{P}}\) is contained in some \({{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\in {\mathsf{C}}\).

To obtain the upper bound on \({{{\rm{CN}}}}({\mathsf{P}})\), we develop the concept of a uniform stabilizer covering. We refer to a stabilizer covering \({\mathsf{U}}={\{{{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\}}_{i}\) of \({\mathsf{P}}\) as uniform if it satisfies the following conditions: (1) For every \({{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\in {\mathsf{U}}\), \(| {{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\cap {\mathsf{P}}|=\Sigma\), and we call Σ the covering power. (2) For all \({P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}\in {\mathsf{P}}\), \(| \{{{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\in {\mathsf{U}}:{P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}\in {{\mathsf{S}}}_{i}\}|=R\), and according to condition (1), the relation \(| {\mathsf{U}}| \times \Sigma=| {\mathsf{P}}| \times R\) holds. By extending the theory of covering arrays37,38,39,40, we prove that for a given \({\mathsf{P}}\), if a uniform stabilizer covering \({\mathsf{U}}\) with covering power Σ exists, an upper bound on \({{{\rm{CN}}}}({\mathsf{P}})\) is given by

Furthermore, we provide a heuristic density-based greedy algorithm41,42 to find a stabilizer covering of size specified in Eq. (12).

For the (ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning, we consider a set \({\mathsf{P}}(w):=\{{P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}:| {P}_{{{{\bf{a}}}}}|=w\}\) where \(| {\mathsf{P}}(w)|=({{n}\atop{w}}){3}^{w}\). For the set \({\mathsf{P}}(w)\), we construct two uniform stabilizer coverings, namely \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\le n/2)}\) with covering power \(({{n}\atop{w}})\) and \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\, > \,n/2)}\) with covering power \(\Omega( \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} 2^{n} )\), corresponding to the regimes w≤n/2 and w > n/2, respectively. We briefly outline their constructions as follows: \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\le n/2)}\) is defined as the collection of \({{\mathsf{S}}}^{(n)}({\mathbb{G}})\) over all \({\mathbb{G}}\), where \({\mathbb{G}}\) is a tuple consisting of n non-identity Pauli operators, with a total of 3n such tuples. Here, \({{\mathsf{S}}}^{(n)}({\mathbb{G}})\) is a stabilizer group generated by \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{(n)}({\mathbb{G}})\), where \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{(n)}({\mathbb{G}})\) is a set that consists of n weight-1 Pauli strings (see Fig. 3). When w > n/2, \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\, > \,n/2)}\) is defined as the collection of \({{\mathsf{S}}}^{({{{\rm{A,B}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},({{{\mathcal{A}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}}))\) over all g and \(({{{\mathcal{A}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}})\), where g is a weight-n Pauli string, and \(({{{\mathcal{A}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}})\) is a partition of the n system qubits such that \(| {{{\mathcal{A}}}}|=2(n-w)\) and \(| {{{\mathcal{B}}}}|=2w-n\). Here, \({{\mathsf{S}}}^{({{{\rm{A,B}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},({{{\mathcal{A}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}}))\) is a stabilizer group generated by the union of {g}, \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{({{{\rm{A}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},{{{\mathcal{A}}}})\), and \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{({{{\rm{B}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}})\), where \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{({{{\rm{A}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},{{{\mathcal{A}}}})\) is a set of \(| {{{\mathcal{A}}}}|\) weight-1 Pauli strings and \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{({{{\rm{B}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}})\) is a set of \(| {{{\mathcal{B}}}}| -1\) weight-2 Pauli strings (see Fig. 4).

Each boxed number indicates the corresponding qubit index. Although we draw \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}={\{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{j}\}}_{j=1}^{2(n-w)}\) and \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}={\{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{j}\}}_{j=1}^{2w-n}\) as contiguous subsets of qubits for simplicity, all of two subsets are considered. Each element of \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{({{{\rm{A}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},{{{\mathcal{A}}}})\) is denoted by a(j), whose \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{j}\)-th component is \({g}_{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{j}}\), and all other components are I. We denote each element of \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{({{{\rm{B}}}})}({{{\bf{g}}}},{{{\mathcal{B}}}})\) by b(j), where \({b}_{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{j}}^{(j)}={{{\mathcal{P}}}}({g}_{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{j}})\), \({b}_{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{j+1}}^{(j)}={{{\mathcal{P}}}}({g}_{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{j+1}})\), and all other components are I. Here, \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}(X)=Y\), \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}(Y)=Z\), and \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}(Z)=X\).

Combining Eq. (12) with the covering powers of \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\le n/2)}\) and \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\, > \,n/2)}\), we derive

where we used \(\log | {\mathsf{P}}(w)|=O(n)\). Finally, by using Eqs. (11) and (13), along with the inequality \({{{\rm{CN}}}}({\bigcup }_{u=0}^{w}{\mathsf{P}}(u))\le {\sum }_{u=0}^{w}{{{\rm{CN}}}}({\mathsf{P}}(u))\), we derive the upper bound on N stated in Theorem 3.

In addition, from Eqs. (6) and (11), we conclude that our bound on \(\,{{{\rm{CN}}}}\,({\mathsf{P}}(w))\) in Eq. (13) is tight within a polynomial factor of n. Although finding the exact value of \({{{\rm{CN}}}}({\mathsf{P}})\) for an arbitrary set \({\mathsf{P}}\) is NP-hard43, by exploiting the specific structure of weight-w Pauli strings, we derive this tight bound.

Additionally, we derive an upper bound on N for the case k > 0 by generalizing the strategy developed for the case k = 0. In particular, by extending the concept of the uniform stabilizer covering, we show that Eqs. (11) and (12) also hold when the k-qubit ancilla is used (see SM Sec. S5 A (Supplementary Material)). Accordingly, we construct a uniform stabilizer covering of \({\mathsf{P}}(w)\) and compute the corresponding covering power. Specifically, we find two uniform stabilizer coverings \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(2w\le k+n)}\) and \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(2w\, > \,k+n)}\), for the regimes 2w≤k + n and 2w > k + n, respectively. Their construction leverages the k ancilla qubits by forming a 2k-qubit Bell pair with k system qubits. Then, for the remaining n − k system qubits, each stabilizer group in \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(2w\le k+n)}\) is designed following the same strategy as in \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\le n/2)}\), and those in \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(2w\, > \,k+n)}\) are built analogously to \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(w\, > \,n/2)}\). Although the resulting upper bound does not match the lower bound in Theorem 2, we present explicit forms of \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(2w\le k+n)}\) and \({{\mathsf{U}}}^{(2w\, > \,k+n)}\), together with their covering powers (see SM Sec. S5 B (Supplementary Material)). According to our construction, when k and w scale proportionally with n, the (ε, δ, w)-Pauli channel learning task can be accomplished with N = O(poly(n)) only for the case k = n. In detail, we find that

where the left-hand side is related with Eq. (12) (see SM Sec. S5 C (Supplementary Material)). This result is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Discussion

We establish that the two fundamental quantum resources, namely the entanglement in the input state and the number of ancilla qubits, have different contributions to the exponential learning advantage. Specifically, we prove that the exponential advantage in Pauli channel learning can be achieved using input states with only inverse-polynomially small entanglement. In contrast, if the number of ancilla qubits is insufficient, even for the easier task of learning a subset of channel parameters, an exponential sample complexity is required. Our results are expected to be useful for quantum channel learning under resource constraints in the NISQ era, such as limited entanglement (e.g., noisy Bell states) or a restricted number of ancilla qubits.

We expect that our result—exponential advantage using only slightly entangled input states—can be extended to a wide range of quantum systems. Potential extensions include learning more general quantum channels beyond the Pauli channel, such as qudit systems and continuous variable systems. Rather than channel learning, applying a similar approach to quantum state learning presents an interesting direction.

Understanding whether concatenated applications of the channel can further reduce the input state entanglement is an intriguing topic for future investigation. Recent studies have shown that such concatenation can reduce the number of measurements; however, the required number of channel applications remains exponential when the number of ancilla qubits is insufficient22,23. Despite these findings, its effect on the input state entanglement has not been investigated.

Determining a tight bound on the sample complexity in the presence of ancilla qubits remains an open problem. Even though addressing a technical issue could lead to a tighter lower bound, as described in SM Sec. S3 E (Supplementary Material), the resulting bound still does not reach the upper bound. Hence, we expect that further advances in the proof techniques for both the upper and lower bounds may ultimately close the remaining gap.

We note that the exponential advantages established in Theorems 1 and 3 can be destroyed by state-preparation and measurement (SPAM) noise. More specifically, under depolarizing noise, the exponential advantage becomes fragile even with access to n-ancilla qubits, as demonstrated in ref. 22. Future research may focus on developing a SPAM-robust learning algorithm and analyzing the resulting sample complexity scaling under limitations on entanglement or the number of ancilla qubits.

Another intriguing future direction is to integrate our framework with SPAM-robust randomized benchmarking (RB) techniques. In particular, Ref. 21 proposes an RB method that utilizes an n-qubit ancilla for sample-efficient benchmarking. This scheme encompasses the case where the input state is a noisy Bell state, and our input state in Eq. (2) also falls within this framework. In addition, since our algorithm associated with Theorem 3 is based on stabilizer covering, the RB method introduced in Ref. 18 can naturally be extended to our setting. We leave a detailed analysis of how the efficiency of the RB scheme depends on SPAM noise for future work.

Data availability

No data has been generated in this work.

References

Shor, P. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 124–134 (1994).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078 (1996).

Harrow, A. W. & Montanaro, A. Quantum computational supremacy. Nature 549, 203–209 (2017).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Zhong, H.-S. et al. Quantum computational advantage using photons. Science 370, 1460–1463 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Strong quantum computational advantage using a superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 180501 (2021).

Madsen, L. S. et al. Quantum computational advantage with a programmable photonic processor. Nature 606, 75–81 (2022).

Morvan, A. et al. Phase transitions in random circuit sampling. Nature 634, 328–333 (2024).

Zhong, H.-S. et al. Phase-programmable Gaussian Boson sampling using stimulated squeezed light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 180502 (2021).

Deng, Y.-H. et al. Gaussian Boson sampling with pseudo-photon-number-resolving detectors and quantum computational advantage. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 150601 (2023).

DeCross, M. et al. The computational power of random quantum circuits in arbitrary geometries. 2406.02501 (2024).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Advances in quantum metrology. Nat. Photon 5, 222–229 (2011).

Polino, E., Valeri, M., Spagnolo, N. & Sciarrino, F. Photonic quantum metrology. AVS Quantum Sci. 2, 024703 (2020).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Information-theoretic bounds on quantum advantage in machine learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 190505 (2021).

Huang, H.-Y. et al. Quantum advantage in learning from experiments. Science 376, 1182–1186 (2022).

Flammia, S. T. & Wallman, J. J. Efficient estimation of Pauli channels. ACM Trans. Quantum Comput. 1, 3:1–3:32 (2020).

Flammia, S. T. & O’Donnell, R. Pauli error estimation via Population Recovery. Quantum 5, 549 (2021).

Chen, S., Cotler, J., Huang, H.-Y. & Li, J. Exponential separations between learning with and without quantum memory. 2111.05881 (2021).

Chen, S., Zhou, S., Seif, A. & Jiang, L. Quantum advantages for Pauli channel estimation. Phys. Rev. A 105, 032435 (2022).

Chen, S., Oh, C., Zhou, S., Huang, H.-Y. & Jiang, L. Tight bounds on Pauli channel learning without entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 180805 (2024).

Chen, S. & Gong, W. Efficient Pauli channel estimation with logarithmic quantum memory. PRX Quantum 6, 020323 (2025).

Coroi, E. & Oh, C. Exponential advantage in continuous-variable quantum state learning. 2501.17633 (2025).

Oh, C. et al. Entanglement-enabled advantage for learning a Bosonic random displacement channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 230604 (2024).

Wallman, J. J. & Emerson, J. Noise tailoring for scalable quantum computation via randomized compiling. Phys. Rev. A 94, 052325 (2016).

Hashim, A. et al. Randomized compiling for scalable quantum computing on a noisy superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041039 (2021).

van den Berg, E., Minev, Z. K., Kandala, A. & Temme, K. Probabilistic error cancellation with sparse Pauli–Lindblad models on noisy quantum processors. Nat. Phys. 19, 1116–1121 (2023).

Ferracin, S. et al. Efficiently improving the performance of noisy quantum computers. Quantum 8, 1410 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500–505 (2023).

Liu, Z.-H. et al. Quantum learning advantage on a scalable photonic platform. Science 389, 1332–1335 (2025).

Seif, A. et al. Entanglement-enhanced learning of quantum processes at scale. 2408.03376 (2024).

Werner, R. F. Quantum states with Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen correlations admitting a hidden-variable model. Phys. Rev. A 40, 4277–4281 (1989).

Bennett, C. H., Bernstein, H. J., Popescu, S. & Schumacher, B. Concentrating partial entanglement by local operations. Phys. Rev. A 53, 2046–2052 (1996).

Terhal, B. M. & Vollbrecht, K. G. H. Entanglement of formation for isotropic states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2625–2628 (2000).

LeCam, L. Convergence of estimates under dimensionality restrictions. Ann. Stat. 1, 38–53 (1973).

Johnson, D. S. Approximation algorithms for combinatorial problems. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 9, 256–278 (1974).

Lovász, L. On the ratio of optimal integral and fractional covers. Discret. Math. 13, 383–390 (1975).

Stein, S. K. Two combinatorial covering theorems. J. Combinatorial Theory, Ser. A 16, 391–397 (1974).

Sarkar, K. & Colbourn, C. J. Upper bounds on the size of covering arrays. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 31, 1277–1293 (2017).

Bryce, R. C. & Colbourn, C. The density algorithm for pairwise interaction testing. Softw. Test. Verif. Reliab. 17, 159–182 (2007).

Bryce, R. C. & Colbourn, C. J. A density-based greedy algorithm for higher strength covering arrays. Softw. Test., Verif. Reliab. 19, 37–53 (2009).

Verteletskyi, V., Yen, T.-C. & Izmaylov, A. F. Measurement optimization in the variational quantum eigensolver using a minimum clique cover. J. Chem. Phys. 152 (2020).

Acknowledgements

M.K. and C.O. were supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grants (No. RS-2024-00431768 and No. RS-2025-00515456) funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT)) and the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) Grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. IITP-2025-RS-2025-02283189 and IITP-2025-RS-2025-02263264). This work was supported by Global Partnership Program of Leading Universities in Quantum Science and Technology (RS-2025-08542968) through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT(MSIT)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. carried out the detailed calculations. C.O. conceptualized the idea and supervised the overall project. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Weiyuan Gong and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, M., Oh, C. On the fundamental resource for exponential advantage in quantum channel learning. Nat Commun 17, 1822 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68532-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68532-y