Abstract

One of the most exploited properties of synthetic materials—and a limiting factor for the broader use of bio-based materials—is their durability and water stability, achieved through strong intermolecular interactions. However, this molecular stability also makes them persistent disruptors of ecological cycles, in contrast with biological structures, which undergo continuous molecular reconfigurations and use their environments to achieve both excellent mechanical properties and biodegradability. This study takes inspiration from chitinous cuticles to produce a biological material that uses water to gain strength and become waterproof. The process involves the vitrification of chitosan with small traces of nickel to create a dynamic network of intermolecular bonds using environmental water, resulting in a biomaterial that increases its strength when wet, an uncommon property previously observed in a few biological structures and never achieved artificially. The approach preserves the biomolecule’s original chemistry and biodegradability while avoiding the strong organic solvents typically associated with bio-derived materials. The study describes the principle and demonstrates its application by manufacturing fully biodegradable and aquatically robust consumables and large objects made from Earth’s second most abundant renewable molecule.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An essential enabling characteristic of synthetic polymers that explains their ubiquitous use in product manufacturing is their stability and persistence in water-based environments1,2, which is strongly linked to their biodegradability—or rather, the lack thereof. Polymeric materials are made suitable for manufacturing by increasing their crystallinity, crosslinking density, and molecular weights, simultaneously providing water stability and the mechanical characteristics to form standalone structures3,4. However, water plays a pivotal role in the metabolic processes that enable biodegradation5, and the stability of these polymers in the presence of water therefore comes at the expense of compostability. The result is materials that, even when they have bio-based origins, can only be biodegraded in specialized facilities—if at all—making their end of life as bad or worse than every other type of persistent synthetic polymer due to their limited recyclability6,7.

That the cost of adapting natural molecules to the current manufacturing paradigm is the loss of their integration with ecological cycles is not because of any limitation of the molecules themselves. Biological systems evolve to use their environment, not isolate themselves from it, producing structures that both develop and perform in water-rich environments by incorporating water as a central element in their designs8,9. The production of the chitinous cuticle of arthropods is an excellent example of this; it is secreted in a gel-like form into water, hardens to form solid exoskeletons for insects and crustaceans, and performs in humid or underwater environments throughout the animal’s life10. The sclerotization process, in which the cuticle transitions from a soft hydrogel to a hard structure, is a complex amalgamation of intertwined processes that involve water transport, molecular reorganizations, and mechanical forces11. Special attention has recently been given to the role that transition metals (e.g., Zn, Cu, Ni) have in this process and the particularities of the complex relationships they have with the organic components of the cuticle (refer to12 for an insightful and extensive review of the use of metal ions in biological structures). The natural availability and biosynthesis rate of some of these structural molecules—specifically chitin polymers—are orders of magnitude greater than the world’s demand for plastics, suggesting that if their industrial isolation were upscaled in an environmentally friendly manner, they could be strong candidates for sustainable manufacturing. However, even when the biomolecules that constitute biological structures are fully isolated, their artificial reassembly into solid materials does not recapitulate the creation process and principles they follow in natural systems13. As a result, despite identical chemistries, the differing molecular organizations of naturally and artificially assembled materials yield completely distinct properties. This chemistry/organization divide is evident in, for example, cellulose-based systems: although a few naturally organized cellulose fibers, such as cotton and linen, even display modest water-induced stiffening (typically <10%) arising from hierarchical structures formed during growth, this behavior does not survive disassembly14. When these biomaterials are disassembled and reconstituted without strong organic solvents, both the modest stiffening and even stability in liquid water are lost. In practice, reconstituted biomaterials are highly susceptible to water and require barrier coatings prior to use in manufacturing15,16.

Here, we report constructs created from an unmodified structural biopolymer formed in a water-based solvent and particularly suitable for use in contact with water. The constructs are made of nickel-doped chitosan (i.e., deacetylated chitin), which incorporates surrounding water into its intermolecular structure, creating a network of weak but highly dynamic water-mediated bonds that avoid failure through internal reconfiguration. The result is a material that almost doubles its strength in contact with water, achieving capacities well beyond those of commodity plastics. This result is particularly significant for two reasons. First, achieving this outcome with a biological material challenges the conventional view of water as an external stressor and instead establishes environmental water as a functional component of a load-bearing network. Second, it emerges in chitin-derived materials, the second-most abundant organic molecules on Earth—surpassed only by cellulose—allowing the proposed technology to potentially scale up to a level that will have a global impact. This result is also particularly timely because chitin-chitosan polymers are becoming central to the development of sustainable and regional manufacturing processes through their role in valorizing organic waste (e.g., food waste) and the local production of nutrients (Fig. 1a)17. Furthermore, the extensive and efficient production of chitin-chitosan in every ecological cycle—particularly by organisms that both produce food and decompose waste—suggests they will even play a key role in creating the efficient, self-sustaining human communities that will allow humanity to colonize other planets18.

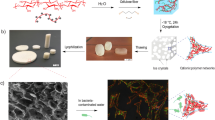

a Conceptual schematic of regional circular production of chitin-derived polymers. Chitin and chitosan, typically byproducts of the shrimp and crab processing industry, are structural components in most heterotrophs used for the bioconversion of organic waste and the local production of nutrients. As part of any ecological cycle, chitin can be reincorporated into circular production cycles through waste management or, if unmanaged, into natural ecological cycles. b Photographs showing the color of vitrified chitosan films with increasing trapped Ni (quantified in Supplementary Fig. 1). Scale bar is 1 cm. c Schematic illustration of plausible Ni ion locations relative to a chitosan chain; the distribution depends on local degree of deacetylation, water content, and crystallinity, and is expected to comprise a mixture of these possibilities. d FTIR spectra of Ni-doped films at different Ni contents, showing that spectral changes associated with added water dominate over Ni-specific contributions. e FTIR region dominated by water’s O-H bond vibrations and normalized to the carbohydrate skeletal vibrations (800–500 cm−1, inherent to the chitosan structure), showing increased Ni-associated intermolecular water content. f X-ray diffraction patterns: pristine vitrified chitosan shows peaks at 9.5° and 20° and a broad amorphous contribution (15–30°); at low Ni content, the peaks’ shift is consistent with a doping process where small molecules take the interstitial space between the organized ones, whereas at higher Ni and water contents the amorphous regions come to dominate the structure. g Representative tensile stress–strain curves of dry Ni-doped films; Ni concentrations below 0.8 M have a limited effect on tensile strength, while at higher concentrations, they increase elasticity without loss of strength, simultaneously achieving strength and toughness, a characteristic functional versatility of structural biomaterials. h Tensile strength before (open bars) and after (filled bars) immersion in water for films prepared from initial Ni concentrations of 0.6–1.4 M; Cs (black) denotes pristine chitosan (no Ni). Elastic moduli and toughness are reported in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, with statistical tests in Supplementary Fig. 2. Measurements include at least three points; data are presented as mean values +/- SD.

This study was inspired by the serendipitous observation that when zinc is removed from the fangs of the sandworm Nereis Virens, they become susceptible to hydration, softening when immersed in water19,20. While most studies on the role of metals in animals’ cuticles center on the protein–metal interaction—specifically, the role of histidine—it is already known that the chitin that form the organic matrix in most cuticles also interact with metals. Indeed, one of the primary uses of chitinous waste from shrimp and crab processing is as a heavy metal flocculant in water treatment systems21. While the studies of the role of metals in arthropod cuticles and biomaterials have primarily focused on mechanical properties22,23, we hypothesized that transition metals might play an essential role in controlling water interactions within chitin-based materials. We specifically used nickel because, although it is not as common as other transition metals (e.g., zinc) in the cuticle, it is a ubiquitous micronutrient necessary for life, is water-soluble, and has shown ample versatility in interacting with chitin and chitosan in theoretical models24,25. However, while phenomena in metal-enriched arthropod cuticles inspired our work, our aim here is not to reproduce arthropod cuticle; we examine a reconstituted chitosan system in which environmental water and trace Ni govern mechanics. Determining whether the principles we uncover are related to processes operating in natural cuticle remains an open question for future research.

Results and discussion

We began our exploration by entrapping varying amounts of nickel within a chitosan structure. Chitosan extracted from discarded shrimp (Penaeus monodon) shells was dispersed at a 3% concentration in a weak solution of acetic acid at the anaerobic limit (1% acetic acid in water; for comparison, table vinegar ranges from 5 to 8%), to which we added nickel chloride dissolved in water at concentrations from 0.6 to 1.4 M. The water was then evaporated, forcing the vitrification of the polymer into a solid film. The first noticeable change from the presence of nickel in the chitosan films was a green color (λ = 520 nm; films without nickel are yellowish), which is characteristic of nickel (II) compounds. This color became more intense as the concentration increased (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Theoretically, and if no factor other than the nickel itself is considered, the most stable location for nickel ions in chitosan polymer chains is the space between the primary and secondary hydroxyl groups of consecutive pyranose rings (Position I in Fig. 1c), where it weakly interacts with the fully coordinated oxygen atom in the ring24. When external elements are also considered, the most stable position is between the primary amino and secondary hydroxyl groups (Position II in Fig. 1c), where the nickel ions can coordinate with water molecules and the sterically available groups of adjacent chitosan chains. It has also been theorized that nickel could take the position between the primary amino and the primary hydroxyl groups of consecutive rings26. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR; Fig. 1d) spectra of the films show a blue shift of the amide II band from 1542 to 1561 cm−1 due to the presence of nickel in the chitosan structure, consistent with interaction with the primary amines (Position II in Fig. 1c). However, a similar blue shift is also apparent in the band located at 1325 cm−1, corresponding to the bending of the -CH2 group, consistent with nickel in the inter-ring position (Position I in Fig. 1c). The direct contribution of nickel to the spectrum can be observed by the moderate modifications of the 500–700 cm−1 region, where the vibrations of the bond between the nickel ions and the hydroxyl groups appear. However, the impact of nickel on the chitosan spectra is not primarily due to its direct interactions, but rather to the changes introduced by the new water molecules associated with the nickel ions.

Nickel forms weak hydrogen bonds with water molecules—up to six when in solution—and while the new interactions with the chitosan chains replace some of those molecules, the nickel-doped films incorporate several times as many water molecules as the number of nickel ions introduced. The effect of this additional water is observable in the band at 1628 cm−1, which corresponds to the bending vibration of the hydroxyl groups in water molecules. While this vibration is overshadowed by the amide I band (1636 cm−1) in pristine chitosan films, it completely dominates the fingerprint region in nickel-doped films, even with the smallest amount of nickel, and grows rapidly as the concentration increases. A similar effect can also be clearly seen in the intensity of the broad band at 3250 cm−1 (Fig. 1e), where the intensity of the vibrations corresponding to the stretching of the O-H bond rapidly increases with the amount of nickel in the system.

The additional water also strongly impacts the crystal structure of the chitosan films (Fig. 1f). Regular chitosan films have a hydrated crystal structure, in which water molecules mediate many of the intermolecular interactions. It has recently been demonstrated that strain stiffening, which reorganizes chitosan films into a more crystalline structure using external forces, also results in closer packing by reducing the free volume and expelling water molecules from the material as new chain–chain direct interactions replace their binding sites27. A similar but opposite effect can be observed in the nickel-doped films, as the additional nickel and its associated water result in lower crystallinity. Considering only the changes in the chitosan organization, the inclusion of nickel and its associated water into the chitosan structure might be (wrongly) seen as plasticization; indeed, a common approach to increasing the flexibility or manufacturability of long polymers is to disrupt their intermolecular bonds, although this occurs at the cost of decreasing their tensile strength. However, in the nickel-doped films, the disruption of the intermolecular bonds by the additional water and the lower crystallinity does not have the expected negative impact on their mechanical characteristics, resonating with recent results on the importance of disorder in biological systems28.

All the samples—independent of their nickel content and therefore their crystallinity—have tensile strengths in the range of 30 to 40 MPa (Fig. 1g), which is similar to commodity plastics. Despite the additional water and lower crystallinity, using low concentrations (less than 0.8 M) of nickel has a minimal impact on the mechanical properties of the films, with insignificant changes in their strength or elasticity compared with pure chitosan films. Beyond 1 M concentrations, however, the strength of the material is preserved while its Young’s modulus—a measure of stiffness—falls significantly, marking the material’s increased ability to be stretched and, therefore, to absorb more energy before breaking—in other words, greater toughness. Introducing nickel into the chitosan structure, therefore, increases both the material’s flexibility as a plasticizer and its strength as a crosslinker, properties that are usually considered incompatible. This result cannot be overstated: the ability of a material to be both tough and strong simultaneously has been a chimeric goal in the field of structural materials that, as a feature unique to biological composites, has been the leading motivation for research into bioinspired materials29. Furthermore, the ability to tune the properties of a biopolymer to different mechanical characteristics without sacrificing strength enables a single material and production process to be adapted to various functions. In biological systems, this phenomenon makes possible, for example, the insect cuticle, which is a continuous and multifunctional structure made of very stiff parts (e.g., wings) and very elastic parts (e.g., joints) with only minor compositional changes. This use in nature of few, but very versatile, materials is the result of intense evolutionary pressure toward efficiency—the so-called survival of the cheapest30. This principle is directly applicable to product design, optimizing both cost and environmental impact by minimizing the number of materials used, simplifying both production and end-of-life management.

While the creation of an unmodified biological material with tunable hardness and constant strength is already an exceptional result, the inclusion of nickel ions in the chitosan matrix provides an even more extraordinary effect: the material gets stronger when it is immersed in water (p = 0.0014, Fig. 1h, and Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Movie 1). The strengths of all the nickel-doped films, except the one with the lowest concentration of nickel, remained constant or increased when immersed in water. This is particularly notable in samples made with a 0.8 M nickel concentration, which showed an increase in strength of almost 50% upon immersion. We hypothesized that there is an optimal balance between the roles of nickel and water in simultaneously enhancing intermolecular bonds through new interactions and disrupting them by preventing direct chain–chain interactions. We therefore focused the rest of the study on the material produced using a 0.8 M concentration of nickel. Analogous experiments performed under identical conditions using Zn²⁺ or Cu²⁺ in place of Ni²⁺ did not produce a comparable water-strengthening response, indicating that the effect depends on the specific coordination chemistry rather than divalent charge alone, and motivating future systematic exploration of other coordination chemistries and material systems.

The nickel-doped films, which in dry conditions have a tensile strength of 36.12 ± 2.21 MPa—within the strength range of commodity plastics (e.g., polypropylene, polystyrene, polylactic acid)—show an increased tensile strength of 53.01 ± 1.68 MPa when immersed in water, placing them in the range of engineering plastics (e.g., polycarbonate, polyethylene terephthalate glycol, polyoxymethylene; Fig. 2a). Using a 0.8 M concentration for fabricating the nickel-doped films appears optimal for achieving this mechanical improvement in water, but at the cost of also incorporating significant amounts of nickel that are irrelevant to that enhancement. This can be observed at the macroscopic level through the leaching of nickel and the behavior of the nickel-doped films upon first immersion in water: freshly made films exhibit a permanent mechanical change relative to their initial state. Subsequently, nickel-doped films that are successively hydrated and then dried at 60 °C for 24 h transition between two mechanically distinct states, both different from that of a freshly made film (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3). This macroscopic change after the first immersion is also observable in the accumulation of nickel on the surface of a freshly made film, which later disappears (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4). Importantly, repeating the wet tests in 0.9% NaCl instead of water yielded indistinguishable strength (47.16 ± 5.16 MPa), indicating the effect is robust to electrolyte screening and not due to long-range electrostatics (Supplementary Fig. 5).

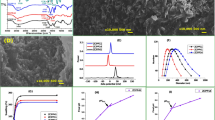

a Ashby plot of tensile strength versus density for natural and synthetic materials, with CsNi films shown in wet (ρ = 1.0142 ± 0.0020 kg/dm3) and dry (ρ = 1.0113 ± 0.0017 kg/dm3) states. b Representative stress–strain curves for CsNi films as prepared (fresh), after first immersion (washed), after drying (dry), and after re-wetting (wet), illustrating reversible wet–dry changes; performance in 0.9% NaCl is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. c SEM images of chitosan (i.e., without nickel) film (Cs), and a nickel-doped film immediately after fabrication (fresh) and after first immersion (washed). Scale bars are 10 micrometers. d C 1 s XPS spectra of a chitosan film without nickel (Cs) and a nickel-doped film before (fresh) and after (washed) first immersion in water. e Schematic of the proposed role of Ni and water in vitrified chitosan: Interchain interactions may be direct (solid lines) or water-mediated (dashed lines). Ni provides additional labile coordination links (blue lines). Among the possibilities is the complete or partial coordination of nickel ions with water, without significant bonds to the polymeric chains, and their release to the environment (This schematic is intended only to illustrate the interaction types in CsNi films; it does not depict chain amorphousness or bending, nor the full range of chitosan–nickel–water interactions). f Thermogravimetric analysis in the water-loss region shows higher water content in fresh nickel-doped chitosan (44%, blue line) than in the same film after its first immersion in water (20%, purple line), and the water content remains stable after 24 h of drying at 60 °C (red line). This is still higher water content than that of pure chitosan (black line) (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for an analysis of weight loss during the first immersion). g Colorimetric assay of Ni release during first immersion. ~13% of the nickel introduced contributes to intermolecular bonding (i.e., one nickel atom per eight saccharide rings), whereas the remaining 87% is released into the surrounding water. After 24 h, no further measurable nickel is released from the films, even when immersed in boiling water for several hours. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD.

At the molecular level, the C 1 s x-ray photoelectron spectrum of the surface of a nickel-doped film shows that three peaks (C-(C, H) (aliphatic), C-(N, O), and C = O/O-C-C) have higher binding energies than the same peaks in a pure chitosan film (Fig. 2d, and Supplementary Table 1). There is also a notable reduction of the area under the deconvoluted C-(N, O) peak (i.e., 286.37 eV), confirming that the primary interaction between nickel and chitosan occurs through the latter’s side functional groups24,26. This observation is further supported by the shift in the peak positions of C3,5 and C2 in the ¹³C NMR (Supplementary Fig. 6), which correspond to the hydroxyl and amide groups. However, after the first immersion of a nickel-doped film in water, those differences disappear, leading to a surface analysis similar to that of pure chitosan films. The same effect is observed in the O 1 s, N 1 s, and Ni 2p spectra, which confirms the Ni +2 oxidation state and the stability of the Ni ions interacting with the side groups of the polymeric chains when the films are immersed in water for the first time (Supplementary Fig. 7), supporting the hypothesis that the permanent change in the material is because the loosely bound nickel and associated water is removed upon first immersion. This hypothesis is also substantiated by the weight loss of the nickel-doped films immediately after immersion, in contrast to the weight gain normally expected of a typically hydrophilic material (e.g., In neutralized chitosan films, their water content increases from 17% of their dry weight to 56% when they are submerged in water) due to water uptake (Supplementary Fig. 8).

In nature, chitinous materials are organized as hydrated crystals in which the relatively long-range interactions between the functional groups of adjacent polymer chains are enabled by intermediate water molecules31. The inclusion of nickel during the formation of the chitosan structure brings a new level of dynamism to the material. Nickel can form weak hydrogen bonds with multiple water molecules—whether dissociated or not—and with the oxygen and nitrogen in the functional groups of the chitosan chains. While some water is bound within the polymeric chains, large amounts are also introduced from the environment alongside the nickel (Fig. 2e). The result is a structure of stiff polymeric chains bound together by a combination of direct interchain bonds and weak, rapidly configurable bonds, mediated by highly motile particles (i.e., nickel and water) trapped within the structure (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). This versatility to bond in multiple ways also includes combinations that do not contribute to the structure, such as nickel and water molecules without significant bonds to the polymeric chains. We hypothesize that these nickel particles and associated water molecules that do not contribute to the structure are the ones released during the first immersion. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that 44% of the weight of a freshly made nickel-doped film is water, but this drops to 20% after the first immersion, which is still significantly higher than the water content in pure chitosan films (13%; Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 11). Similarly, even while the films keep their strength underwater, 87.18 ± 2.72% of the entrapped nickel is weakly bound to the chitosan and is released during the first immersion (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). This indicates that, despite the amount of nickel introduced, only 1 nickel ion per 7.91 pyran rings is required to produce the water-strengthening effect in chitosan. In a macroscopic context, this means that the nickel content of a discarded AAA battery (2.2 g) would be sufficient to manufacture more than a dozen typical drinking cups (4.7 g each) using nickel-doped chitosan.

The post-wash Ni content (~1 Ni²⁺ per eight pyranose rings) constrains site occupancy and argues against a dense lattice of permanent multidentate chelates. As discussed above, spectroscopy and structural data indicate that the residual Ni²⁺ engages primarily with side groups while retaining a substantial hydration shell, and that Ni/water incorporation reduces crystallinity. Together with the large initial loss of loosely bound Ni on first immersion ( ~ 87%) while wet strengthening persists, these observations support a water-mediated, dynamically reconfigurable network rather than a permanently cross-linked architecture. This was confirmed by chelating coordinated Ni²⁺ with 0.5 M EDTA for two hours, which collapses the films into a jelly-like material indistinguishable from chitosan (data not shown), indicating that removal of inner-sphere Ni abolishes the effect. Consistent with this picture, the wet tensile strength increases near neutral/alkaline pH (Supplementary Fig. 14), as deprotonation facilitates Ni²⁺-amine interactions. Together, these data support a mechanism in which Ni²⁺-amine interactions and water-mediated hydrogen-bond networks enable wet-state strengthening, rather than extensive, rigid Ni-polymer chelation.

The release of the inconsequential nickel during the first immersion could be seen as an optimization of the material, in which the arbitrary entrapment of the nickel needed to saturate the system is followed by a process that removes all but the nickel that contributes to the material’s structure. This process is carried out in water, which is also the environment in which the films form. The resulting waste from the optimization process is therefore itself an ingredient (i.e., nickel and water) for producing the films. With this in mind, we developed a production cycle in which the water used to remove the inconsequential nickel is used as an input for fabricating films (Fig. 3a). Using this zero-waste process, we produced several objects with an approach similar to the use of chitosan in product manufacturing—that is, vitrifying it on a positive mold15. This approach enabled the production of common plasticware, such as containers and cups (Fig. 3b). Note that the purpose of these objects was to explore the material’s malleability rather than its ability to replace products that might no longer be justifiable in a society that can use biological materials and regionalized production. Nevertheless, the nickel-doped chitosan containers showed that the biological molecule not only gains strength in aqueous environments but can also retain water as effectively as common plastics, demonstrating the material’s suitability for such tasks (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Movie 2). The studies were extended to include the production of negative replicas, which involves maintaining contact between the material and the mold during the vitrification process to account for the inherent shrinking of the object as it forms. To overcome this limitation, we fabricated a random positioning machine (a two-axis clinostat; Fig. 3d, and Supplementary Movie 3) with two independently perpendicular frames and an attached negative mold. The continuous repositioning of the mold forced the polymeric solution to maintain contact during vitrification, enabling the molding of closed geometries and a qualitative improvement in the esthetics of the objects compared to those produced with positive molds (Fig. 3e).

a Diagram of zero-waste production of Ni-doped chitosan objects. The inconsequential nickel released during the optimization of one object is used as a primary component for the next by topping up the nickel content. The system ensures 100% utilization of nickel despite the need to saturate the material with large amounts of it during vitrification to achieve the water-strengthening effect (see Fig. 1h). The top-left corner shows the process’s actual inputs and outputs, expressed as weights. As a reference, the drinking cup in the next panel weighs 4.7 g. b Replica of a drinking cup made of nickel-doped chitosan formed using a negative mold (i.e., the material vitrifies against the mold’s outside walls). On the right is the same object after the inconsequential nickel has been removed by immersion in water—a process that has no apparent impact on its geometry. See Supplementary Fig. 13 for closer images of the color change due to the release of the inconsequential nickel. c Images of a nickel-doped chitosan cup filled with water, demonstrating the material’s impermeability. A detailed recording of the first 24 h is in Supplementary Movie 2. d Picture of the clinostat used to replicate negative molds for the nickel-doped chitosan. The continuous movement forces the material to vitrify against the inner walls, enabling the fabrication of closed geometries and producing more accurate, high-quality objects (see Supplementary Movie 3 for more detailed information). e Comparison of the same objects fabricated using negative (i.e., with the clinostat in the previous panel) and positive molds. f An example of a three-square-meter film made of nickel-doped chitosan used to test the process’s scalability. Detailed information on this construct is provided in Supplementary Movie 4.

In the last few decades, the materials proposed for ecologically integrated manufacturing have focused on recovery processes32 or uncommon biological components with limited scalability33. The approach here is based on the biomimetic coordination of a transitional metal with chitin, Earth’s second-most abundant organic material, with an estimated renewable production rate of 1011 tonnes per year34—the equivalent of three centuries of plastic production. Such production is sustainable, seamlessly integrated into Earth’s ecological cycles, and easily reproducible in urban environments through the bioconversion of food and other organic wastes17. This unparalleled bioavailability enables the potential scaling of the results presented here to unprecedented levels for a new technology by avoiding the need to develop an industrial biosynthesis but, more importantly, the theoretical upscaling of production to quantities with a global impact and the regionalization of that production. To explore the potential for upscaling—even within the limited confines of a research laboratory—we produced a 1 m2 chitosan-doped film and tested its ability to hold weight after 24 h of water immersion (Supplementary Movie 4). Building on the initial scale-up, we produced a film three times larger without notable processing challenges (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Movie 4); importantly, these large-area films remained mechanically robust during handling and exhibited similar macroscopic mechanical behavior to smaller-area samples, demonstrating an absence of scalability restrictions and highlighting the potential for rapid scaling of the results and principles presented here to ecologically relevant scales.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the interaction between a transition metal—specifically nickel—and chitosan creates unique material properties for the molecule in its native form, from the tunability of elastic properties without impacting material strength to improving mechanical performance underwater. Unlike the usual approach of fitting biological molecules into the synthetic polymers paradigm, the production process presented here applies the principles of bioinspired manufacturing by adapting biological strategies to use unmodified biological components, applying water-based and environmentally friendly chemistries, and minimizing waste production35,36. This strategy preserves the natural biodegradability of chitin-derived polymers (Supplementary Fig. 15), without relying on special conditions, human intervention, or recovery.

The results presented here represent an approach to manufacturing in biological environments and a departure from the current view that assumes inertness is unavoidably associated with resilience. In the case of polymer-based materials, resilience is achieved through heavily crosslinked long molecules that depend on strong and exhaustive internal links to produce materials that are unresponsive to the surrounding environment. Here, resilience is achieved in a biomimetic way, using the environment instead of fighting it, relying on water transport between the nickel-doped chitosan and the environment to create a dynamic structure of weak and long-range intermolecular bonds in continuous reconfiguration.

Because of the mechanical properties of the nickel-doped chitosan in water-based environments, the absence of a human immune response, and existing FDA approval for medical uses of both nickel37 and chitosan38 individually, we foresee applications of these results in the medical field and as a waterproof coating for biomaterials35 while the proposed shaping technologies are perfected and upscaled for general use (refer to the supplementary material for an additional discussion on health and environmental impact). However, in a world that generates 400 million tonnes of persistent solid waste every year, much of it specifically for its performance in water environments39, we believe the approach presented here and the principles and materials upon which it is based will have implications at an unprecedented scale. They mark the potential for a paradigm shift toward bioinspired manufacturing based on ubiquitous biological materials, regional production, and environmental integration, which can address the limitations of current manufacturing and curb humanity’s persistent waste production40.

Methods

Materials

Chitosan was sourced from shrimp-processing factory byproducts in India, provided by iChess Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Industrial-grade acetic acid and nickel chloride hexahydrate (98%, Sigma-Aldrich) were obtained from local vendors and used as received.

Film fabrication

Films were fabricated by dissolving chitosan flakes in 1% acetic acid under continuous stirring for 48 h at room temperature to prepare a 3 wt% chitosan solution. Nickel chloride solutions at concentrations ranging from 0.6 to 1.4 M were prepared separately in 10 mL of distilled water. Both solutions (i.e., chitosan and nickel) were mixed through continuous stirring for 6 h to ensure the uniform distribution of nickel ions in the chitosan solution. The solution was poured into a Petri dish to prepare the standard samples, which were then dried in an air oven at 40 °C for 24 h. However, similar results have been obtained with other molds and drying conditions (e.g., 3 m2 films dried at room temperature; see Supplementary Movies 3 and 4). The samples are coded as Cs, 0.6 M, 0.8 M, 1.0 M, 1.2 M, 1.4 M relative to the Molar concentration of Ni in the original solution. Depending on the state of the film, they are also labeled as fresh for chitosan and chitosan-nickel films or constructs after they are dried/vitrified from the original solution. Washed for nickel-doped constructs (e.g., films) that have been immersed in water for more than 24 h at least once, and the inconsequential Ni has been removed. Wet for constructs currently or recently immersed in water and still soaked, retaining large amounts of excess water. Dry for constructs that have been oven-dried and have had excess water removed. Appropriate safety equipment was used during reagent handling.

The chitosan films (i.e., without nickel) used to compare the underwater properties of pure chitosan with nickel-doped chitosan were neutralized with 1 M NaOH to prevent dissolution upon immersion. Freshly prepared films were washed five times in a beaker containing NaOH solution, then rinsed in double-distilled water in another container. For all other characterizations, the pure chitosan and nickel-doped chitosan films are prepared using the same procedure (i.e., without neutralization).

Structural characterization

The crystallographic structures of the polymers were determined using an Empyrean X-ray diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., UK) with a Cu anode, generating Cu Kα radiation. The patterns were recorded at room temperature using continuous scanning between 5 and 60°.

Optical characterization

UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 1800, Shimadzu Corp., JP) was used to measure the light absorption of the films in the 200–800 nm wavelength range. Beer-Lambert’s law was used to determine the concentration of nickel released. Samples with a fixed Ni concentration were used as references to determine the unknown Ni concentration in a solution. The standard data were obtained by plotting absorbance versus the known Ni concentrations (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 M). From this plot, the unknown concentration of Ni in water (falling in the range between 0 and 1.6 M) can be determined with absorbance values.

Surface morphology imaging

The morphology of the samples was characterized using Scanning electron microscopy (JSM-7600F, JEOL Ltd., Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. Before imaging, samples were gold-coated to render the surface conductive.

Molecular representations

Three-dimensional representations of the chitosan, nickel, and water molecules were created using 3D Studio (Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, USA). The atomic positions in the 3D space and atomic radii were sourced from PubChem (National Center for Biotechnology Information, USA). In Fig. 2e, the polymer chains have been ‘flattened’ (i.e., molecular bonds’ out-of-plane twists have been removed) for illustrative purposes.

Molecular level characterizations

Fourier transform Infrared (FTIR) using a spectrometer (VERTEX 70 FT-IR, Bruker Corp. USA) in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) between 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Chitosan’s degree of deacetylation (DD) was calculated by comparing the absorbance of the measured peak at 1650 cm−1 (which is proportional to the DA) with that of the reference peak at 3450 cm−1 (which is independent of the DA)10. The DD of 86.82 ± 2.86% was determined using the equation:

The orbital level information was obtained using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Axis Supra Plus, Kratos Analytical, UK). The data were acquired using Al Kα as the X-ray source. The wide scan had a pass energy of 160 eV (1 eV step size), and the narrow scan was 20 eV (0.1 eV step size). The data obtained were analyzed using CasaXPS (Casa Software Ltd., GB). A standard carbon C1s peak (284.8 eV) was used for reference, and Shirley background was used to correct the spectrum. The data were deconvoluted using a Gaussian Lorentzian (GL-30) line shape function to determine the films’ oxidation state and elemental composition.

Chitosan intrinsic viscosity and molecular weight

The intrinsic viscosity and viscosity-average molecular weight were determined using an Ubbelohde capillary viscometer with a capillary diameter of 0.8 mm. We tested four concentrations of a chitosan solution in a solvent system composed of 0.3 M acetic acid and 0.2 M sodium acetate at a temperature of 25 °C11. The experimental results were then used in the Mark–Houwink equation to determine the molecular weights:

Where [η] is the intrinsic viscosity, K and α are Mark-Houwink constants. K and α were previously determined under identical conditions to be 0.74 × 10−3 and 0.76, respectively. The viscosity-average molecular weight of the chitosan used in these experiments was 189,520.5 ± 1,179.2 Da.

Mechanical studies

Mechanical strength was measured using a universal testing machine (UTM; Instron 5943) for both dry and wet samples. Dog-bone-shaped samples with a test dimension of 10 × 2 cm (L × W) were used for the tensile tests. The measurements were conducted at room temperature, with a RH of 70%. Wet samples were immersed in water for 24 h and then removed immediately prior to measurement. A customized setup consisting of a water container with a pass-through attachment to the tensile tester container was engineered to accurately measure the samples’ underwater performance. Wet tensile testing was conducted with a gauge length submersion of 7 cm, a controlled strain rate of 1 mm/min, and grip forces of ~1.5 kN applied at an air pressure of 6–8 bar. This configuration ensured that the sample remained in water during the tensile test. The dry samples were tested in the empty container to avoid introducing variability between the dry and wet tests. See Supplementary Movie 1 for an example of a test.

To test the effects of solution acidity and alkalinity on mechanical performance, the tensile strength of the Cs-Ni samples was measured at pH 4, 7, and 10 using buffer solutions. A 0.9% NaCl solution was used to evaluate the effect of a saline environment.

Thermogravimetric analysis

The water transport and decomposition of the polymer matrix were studied using a Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA Q50) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). The data were recorded over the temperature ranges 30 to 600 °C (TGA) and 30 to 300 °C (DSC) at a ramp rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

The changes in the chemical structure as a function of Ni content were studied using 400 MHz solid-state NMR (Bruker).

Hydro stability

The polymer swelling behavior was studied using 5 cm × 3 cm films immersed in water, and the films were weighed every hour for 24 h. The swelling degree was determined using the relation.

Where WW and Wo are the weight of a wet sample at a given time point and its initial (dry) weight, respectively.

Reuse of Nickel in water

The Nickel released in water was reused for manufacturing new composite films, following the same procedure described in the methodology to prepare composite films, with the only difference that the same amount of nickel that remained in the washed construct is added to the wastewater to achieve the right concentration for the formation of new constructs.

Construction of clinostat

A two-axis clinostat, a random positioning machine with two independently perpendicular frames usually utilized to simulate microgravity environments, was equipped with a positive mold to create a negative replica of CsNi composite-based objects. The frame, constructed with aluminum profiles, is powered by two stepper motors and controlled by an Arduino UNO microcontroller, which independently operates both motors. We used the AccelStepper library to program the system. The system produces a continuous movement between two positions or moves to random positions at a pre-determined rate.

Biodegradation test

A standard soil burial test was used to assess the biodegradation of the CsNi samples in environmental conditions. Individually weighed groups of samples were buried in garden soil, and degradation was monitored until the material’s half-life (i.e., half of the material had degraded) was reached, which occurred after ~four months (128 days). The samples were collected from the soil at 20-day intervals, and mass loss was assessed by weighing them after washing and drying. The mass loss of various degraded samples was measured to assess the extent of degradation in the soil over time.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Brydson, J. A. Plastics materials. (Elsevier, 1999).

Thompson, R. C. et al. Our plastic age. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 364, 1973–1976 (2009).

Reeve, M. S. et al. Polylactide stereochemistry: effect on enzymic degradability. Macromolecules 27, 825–831 (1994).

Zambrano, M. C., Pawlak, J. J. & Venditti, R. A. Effects of chemical and morphological structure on biodegradability of fibers, fabrics, and other polymeric materials. BioResources 15, 9786–9833 (2020).

Woodard, L. N. & Grunlan, M. A. Hydrolytic degradation and erosion of polyester biomaterials. ACS Macro Lett. 7, 976–982 (2018).

Rezvani Ghomi, E. et al. The life cycle assessment for polylactic acid (PLA) to make it a low-carbon material. Polymers (Basel) 13, 1854 (2021).

Van Roijen, E. C. & Miller, S. A. A review of bioplastics at end-of-life: Linking experimental biodegradation studies and life cycle impact assessments. Resour., Conserv. Recycling 181, 106236 (2022).

Dargaville, B. L. & Hutmacher, D. W. Water as the often neglected medium at the interface between materials and biology. Nat. Commun. 13, 4222 (2022).

Shen, S. C. et al. Robust myco-composites: a biocomposite platform for versatile hybrid-living materials. Mater. Horiz. 11, 1689–1703 (2024).

Neville, A. C. et al. Biology of the arthropod cuticle. 4, (Springer-Verlag, 1975).

Vincent, J. F. V. & Hillerton, J. E. The tanning of insect cuticle—A critical review and a revised mechanism. J. Insect Physiol. 25, 653–658 (1979).

Khare, E., Holten-Andersen, N. & Buehler, M. J. Transition-metal coordinate bonds for bioinspired macromolecules with tunable mechanical properties. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 421–436 (2021).

Aizenberg, J. & Fratzl, P. Biological and biomimetic materials. Adv. Mater. 21, 387–388 (2009).

Grishanov, S. 2 - Structure and properties of textile materials, in Handbook of Textile and Industrial Dyeing, M. Clark, Editor. Woodhead Publishing. 28–63 (2011).

Fernandez, J. G. & Ingber, D. E. Manufacturing of large-scale functional objects using biodegradable chitosan bioplastic. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 299, 932–938 (2014).

Leceta, I., Guerrero, P. & de la Caba, K. Functional properties of chitosan-based films. Carbohydr. Polym. 93, 339–346 (2013).

Sanandiya, N. D. et al. Circular manufacturing of chitinous bio-composites via bioconversion of urban refuse. Sci. Rep. 10, 4632 (2020).

Shiwei, N., Dritsas, S. & Fernandez, J. G. Martian biolith: a bioinspired regolith composite for closed-loop extraterrestrial manufacturing. PLOS ONE 15, e0238606 (2020).

Broomell, C. C. et al. Critical role of zinc in hardening of Nereis jaws. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3219–3225 (2006).

Chou, C.-C. et al. Ion effect and metal-coordinated cross-linking for multiscale design of Nereis jaw inspired mechanomutable materials. ACS Nano 11, 1858–1868 (2017).

Onsøyen, E. & Skaugrud, O. Metal recovery using chitosan. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. (Oxf., Oxfs.) 49, 395–404 (1990).

Kim, B. J. et al. Mussel-Mimetic Protein-Based Adhesive Hydrogel. Biomacromolecules 15, 1579–1585 (2014).

Tamura, H., Nagahama, H. & Tokura, S. Preparation of Chitin Hydrogel Under Mild Conditions. Cellulose 13, 357–364 (2006).

Gomes, J. R. B., Jorge, M. & Gomes, P. Interaction of chitosan and chitin with Ni, Cu and Zn ions: A computational study. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 73, 121–129 (2014).

Khare, E. et al. Molecular understanding of Ni2+-nitrogen family metal-coordinated hydrogel relaxation times using free energy landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2213160120 (2023).

Braier, N. C. & Jishi, R. A. Density functional studies of Cu2+ and Ni2+ binding to chitosan. J. Mol. Structure: THEOCHEM 499, 51–55 (2000).

Rukmanikrishnan, B., Tracy, K. J. & Fernandez, J. G. Secondary reorientation and hygroscopic forces in chitinous biopolymers and their use for passive and biochemical actuation. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2300639 (2023).

Hsu, C. C., Buehler, M. J. & Tarakanova, A. The order-disorder continuum: linking predictions of protein structure and disorder through molecular simulation. Sci. Rep. 10, 2068 (2020).

Ritchie, R. O. The conflicts between strength and toughness. Nat. Mater. 10, 817–822 (2011).

Vincent, J. F. V. Survival of the cheapest. Mater. Today 5, 28–41 (2002).

Okuyama, K. et al. Molecular and crystal structure of hydrated chitosan. Macromolecules 30, 5849–5855 (1997).

Shieh, P. et al. Cleavable comonomers enable degradable, recyclable thermoset plastics. Nature 583, 542–547 (2020).

McAdam, B. et al. Production of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and factors impacting its chemical and mechanical characteristics. Polymers (Basel) 12, 2908 (2020).

Kurita, K. Controlled functionalization of the polysaccharide chitin. Prog. Polym. Sci. 26, 1921–1971 (2001).

Sanandiya, N. D. et al. Large-scale additive manufacturing with bioinspired cellulosic materials. Sci. Rep. 8, 8642 (2018).

Ng, S., Song, B. & Fernandez, J. G. Environmental attributes of fungal-like adhesive materials and future directions for bioinspired manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 282, 125335 (2021).

FDA, U. Biological responses to metal implants. Food and Drug Administration, 1–143 (2019).

Dornish, M., Kaplan, D. S. & Arepalli, S. R. Regulatory Status of Chitosan and Derivatives, in Chitosan-Based Systems for Biopharmaceuticals, 463–481 (2012).

Lebreton, L. et al. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Sci. Rep. 8, 4666 (2018).

Fernandez, J. G. & Dritsas, S. The biomaterial age: the transition toward a more sustainable society will be determined by advances in controlling biological processes. Matter 2, 1352–1355 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Cedric Finet from the National University of Singapore (NUS), the Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (IMRE), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (ASTAR) for the chemical analysis. We want to thank Dr. Xueliang Li for his assistance with the XRD measurements and Ms. Sarah Wasifa Ferdousi for her help building the clinostat.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. and J.G.F. conceived and designed the study and experiments. A.K. performed the material characterization measurements. J.G.F. designed and built the clinostat. A.K. and J.G.F. analyzed and interpreted the data, discussed the results, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.K. and J.G.F. are inventors on a patent application related to the materials and/or methods described in this work. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wenzhuo Wu, Dongyeop Oh, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kompa, A., G. Fernandez, J. Stronger when wet: Aquatically robust chitinous objects via zero-waste coordination with metal ions. Nat Commun 17, 1397 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69037-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69037-4