Abstract

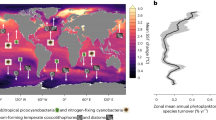

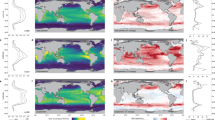

Geological records suggest that marine phytoplankton might have arisen in the Proterozoic while zooplankton remained absent, and marine productivity was not excessively low. However, quantitative estimates of phytoplankton biomass and net primary productivity remain elusive. Here, we use the Community Earth System Model version 1.2.2, modifying biological module and boundary conditions, to simulate marine biogeochemical cycles in the Proterozoic. The simulations demonstrate that, within the expected range of nutrient levels, phytoplankton at sea surface was more than 2 times denser than present, sustaining a greener ocean due to the absence of predators. Heavier surface chlorophyll in the Proterozoic would block sunlight from reaching subsurface layers. This so-called self-shielding effect would decrease subsurface net primary productivity significantly. Simulations show that, through the combined influence of low nitrate level under a low-oxygen environment, the absence of diatoms, and self-shielding, the Proterozoic net primary productivity was only approximately 60% and 30% of the present level in warm (almost ice-free) and cold (sea-ice reaches around 30°N/S) periods, respectively. These findings are subject to uncertainties in model framework and Proterozoic nutrients levels; a slightly less green ocean or more productive ocean was possible if the phosphorus level was much lower or higher than the present level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The simulation results used for the present study are archived on Zenodo with the identifier https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18489467. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code of CESM1.2.2 can be accessed at https://github.com/ESCOMP/CESM. The NCAR Command Language (NCL) version 6.2.2 (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6WD3XH5) is used for graphing.

References

Hoffman, P. F. et al. Snowball Earth climate dynamics and Cryogenian geology-geobiology. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600983 (2017).

Kasting, J. F. Methane and climate during the Precambrian era. Precambrian Res. 137, 119–129 (2005).

Butterfield, N. J. Proterozoic photosynthesis–a critical review. Palaeontology 58, 953–972 (2015).

Crockford, P. W. et al. Triple oxygen isotope evidence for limited mid-Proterozoic primary productivity. Nature 559, 613–616 (2018).

Brocks, J. J. et al. The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals. Nature 548, 578–581 (2017).

Wang, X., Dong, L., Ma, H., Lang, X. & Wang, R. Primary productivity recovery and shallow-water oxygenation during the Sturtian deglaciation in South China. Glob. Planet. Change 241, 104546 (2024).

Lenton, T. M., Boyle, R. A., Poulton, S. W., Shields-Zhou, G. A. & Butterfield, N. J. Co-evolution of eukaryotes and ocean oxygenation in the Neoproterozoic era. Nat. Geosci. 7, 257–265 (2014).

Tziperman, E., Halevy, I., Johnston, D. T., Knoll, A. H. & Schrag, D. P. Biologically induced initiation of Neoproterozoic snowball-Earth events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 15091–15096 (2011).

Rothman, D. H., Hayes, J. M. & Summons, R. E. Dynamics of the Neoproterozoic carbon cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100, 8124–8129 (2003).

Feulner, G., Hallmann, C. & Kienert, H. Snowball cooling after algal rise. Nat. Geosci. 8, 659–662 (2015).

Kump, L. R. The rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature 451, 277–278 (2008).

Planavsky, N. J. et al. Widespread iron-rich conditions in the mid-Proterozoic ocean. Nature 477, 448–451 (2011).

Liu, P. et al. Large influence of dust on the Precambrian climate. Nat. Commun. 11, 4427 (2020).

Motomura, K. et al. The nitrate-limited freshwater environment of the late Paleoproterozoic Embury Lake Formation, Flin Flon belt. Can. Chem. Geol. 616, 121234 (2023).

Kang, J., Gill, B., Reid, R., Zhang, F. & Xiao, S. Nitrate limitation in early Neoproterozoic oceans delayed the ecological rise of eukaryotes. Sci. Adv. 9, eade9647 (2023).

Laakso, T. A. & Schrag, D. P. A small marine biosphere in the Proterozoic. Geobiol 17, 161–171 (2019).

Guilbaud, R. et al. Phosphorus-limited conditions in the early Neoproterozoic ocean maintained low levels of atmospheric oxygen. Nat. Geosci. 13, 296–301 (2020).

Planavsky, N. J. et al. The evolution of the marine phosphate reservoir. Nature 467, 1088–1090 (2010).

Cebrian, J., Stutes, A. L. & Corcoran, A. A. Effects of nutrient enrichment and shading on sediment primary production and metabolism in eutrophic estuaries. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 312, 29–43 (2006).

Estes, J. A. et al. Trophic Downgrading of Planet Earth. Science 333, 301–306 (2011).

Eckford-Soper, L. K., Andersen, K. H., Hansen, T. F. & Canfield, D. E. A case for an active eukaryotic marine biosphere during the Proterozoic era. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 119, e2122042119 (2022).

Laakso, T. A. & Schrag, D. A theory of atmospheric oxygen. Geobiology 15, 366–384 (2017).

Claire, M. W., Catling, D. C. & Zahnle, K. J. Biogeochemical modelling of the rise in atmospheric oxygen. Geobiology 4, 239–269 (2006).

Gianchandani, K., Halevy, I., Gildor, H., Ashkenazy, Y. & Tziperman, E. Production of Neoproterozoic banded iron formations in a partially ice-covered ocean. Nat. Geosci. 17, 298–301 (2024).

Ramme, L., Ilyina, T. & Marotzke, J. Moderate greenhouse climate and rapid carbonate formation after Marinoan snowball Earth. Nat. Commun. 15, 3571 (2024).

Cao, X. et al. Earth’s tectonic and plate boundary evolution over 1.8 billion years. Geosci. Front. 15, 101922 (2024).

Li, Z.-X. et al. Assembly, configuration, and break-up history of Rodinia: a synthesis. Precambrian Res. 160, 179–210 (2008).

Liu, P., Liu, Y., Gu, S., Hoffman, P. & Li, S. A positive cooling feedback for the Neoproterozoic snowball Earth initiation due to weakening of ocean ventilation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102020 (2023).

Long, M. C. et al. Simulations with the marine biogeochemistry library (MARBL). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 13, e2021MS002647 (2021).

Sims, P. A., Mann, D. G. & Medlin, L. K. Evolution of the diatoms: insights from fossil, biological and molecular data. Phycologia 45, 361–402 (2006).

Steinberg, D. K. & Landry, M. R. Zooplankton and the ocean carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9, 413–444 (2017).

Holder, C. & Gnanadesikan, A. How well do Earth System Models capture apparent relationships between phytoplankton biomass and environmental variables? Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007701 (2023).

Marinov, I., Doney, S. & Lima, I. Response of ocean phytoplankton community structure to climate change over the 21st century: partitioning the effects of nutrients, temperature and light. Biogeosciences 7, 3941–3959 (2010).

Beckmann, A. & Hense, I. Beneath the surface: characteristics of oceanic ecosystems under weak mixing conditions—a theoretical investigation. Prog. Oceanogr. 75, 771–796 (2007).

Holmer, M. & Bondgaard, E. J. Photosynthetic and growth response of eelgrass to low oxygen and high sulfide concentrations during hypoxic events. Aquat. Bot. 70, 29–38 (2001).

Twilley, R. R., Kemp, W. M., Staver, K. W., Stevenson, J. C. & Boynton, W. R. Nutrient enrichment of estuarine submersed vascular plant communities. 1. Algal growth and effects on production of plants and associated communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 23, 179–191 (1985).

Moore, J. K., Doney, S. C. & Lindsay, K. Upper ocean ecosystem dynamics and iron cycling in a global three-dimensional model. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 18, GB4028 (2004).

Moore, C. et al. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 701–710 (2013).

McGlathery, K. J. Macroalgal blooms contribute to the decline of seagrass in nutrient-enriched coastal waters. J. Phycol. 37, 453-456 (2001).

Huntington, B. E. & Boyer, K. E. Effects of red macroalgal (Gracilariopsis sp.) abundance on eelgrass Zostera marina in Tomales Bay, California, USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 367, 133–142 (2008).

Churilova, T. Y., Suslin, V., Moiseeva, N. & Efimova, T. Phytoplankton bloom and photosynthetically active radiation in coastal waters. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 86, 1084–1091 (2020).

Sarangi, R., Chauhan, P. & Nayak, S. Phytoplankton bloom monitoring in the offshore water of Northern Arabian Sea using IRS-P4 OCM Satellite data. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 30, 214–221 (2001).

Raghavan, B. et al. Summer chlorophyll-a distribution in eastern Arabian Sea off Karnataka-Goa coast from satellite and in-situ observations. Remote Sens. Mar. Environ. 6406, 64060W (2006).

Heck, K. L. Jr., Pennock, J. R., Valentine, J. F., Coen, L. D. & Sklenar, S. A. Effects of nutrient enrichment and small predator density on seagrass ecosystems: an experimental assessment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 1041–1057 (2000).

Shiomoto, A., Tadokoro, K., Nagasawa, K. & Ishida, Y. Trophic relations in the subarctic North Pacific ecosystem: possible feeding effect from pink salmon. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 150, 75–85 (1997).

Odate, T. Plankton abundance and size structure in the northern North Pacific Ocean in early summer. Fish. Oceanogr. 3, 267–278 (1994).

Carpenter, S. R. et al. Trophic cascades, nutrients, and lake productivity: whole-lake experiments. Ecol. Monogr. 71, 163–186 (2001).

Okey, T. A. et al. Simulating community effects of sea floor shading by plankton blooms over the West Florida Shelf. Ecol. Model. 172, 339–359 (2004).

Meyercordt, J. & Meyer-Reil, L.-A. Primary production of benthic microalgae in two shallow coastal lagoons of different trophic status in the southern Baltic Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 178, 179–191 (1999).

Morel, A. & Bricaud, A. Theoretical results concerning light absorption in a discrete medium, and application to specific absorption of phytoplankton. Deep Sea Res. Part A Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 28, 1375–1393 (1981).

Deng, L. et al. Estimation of vertical size-fractionated phytoplankton primary production in the northern South China Sea. Ecol. Indic. 135, 108546 (2022).

Sciascia, R., De Monte, S. & Provenzale, A. Physics of sinking and selection of plankton cell size. Phys. Lett. A 377, 467–472 (2013).

Mills, D. B., Vuillemin, A., Muschler, K., Coskun, ÖK. & Orsi, W. D. The Rise of Algae promoted eukaryote predation in the Neoproterozoic benthos. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt2147 (2025).

Lewis, M. R., Carr, M.-E., Feldman, G. C., Esaias, W. & McClain, C. Influence of penetrating solar radiation on the heat budget of the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Nature 347, 543–545 (1990).

Krüger, O. & Graßl, H. Southern Ocean phytoplankton increases cloud albedo and reduces precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L08809 (2011).

Wang, S., Maltrud, M. E., Burrows, S. M., Elliott, S. M. & Cameron-Smith, P. Impacts of shifts in phytoplankton community on clouds and climate via the sulfur cycle. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 1005–1026 (2018).

Mitchell, R. N. & Kirscher, U. Mid-Proterozoic day length stalled by tidal resonance. Nat. Geosci. 16, 567–569 (2023).

Zhou, M. et al. Earth-Moon dynamics from cyclostratigraphy reveals possible ocean tide resonance in the Mesoproterozoic era. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn7674 (2024).

Laakso, T. A. & Schrag, D. P. Regulation of atmospheric oxygen during the Proterozoic. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 388, 81–91 (2014).

Rickaby, R. E. M. & Eason Hubbard, M. R. Upper ocean oxygenation, evolution of RuBisCO and the Phanerozoic succession of phytoplankton. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 140, 295–304 (2019).

Yee, D. P. et al. The V-type ATPase enhances photosynthesis in marine phytoplankton and further links phagocytosis to symbiogenesis. Curr. Biol. 33, 2541–2547.e5 (2023).

Armstrong, R. A., Lee, C., Hedges, J. I., Honjo, S. & Wakeham, S. G. A new, mechanistic model for organic carbon fluxes in the ocean based on the quantitative association of POC with ballast minerals. Deep Sea Res. Part II 49, 219–236 (2002).

Letscher, R. T., Moore, J. K., Teng, Y.-C., Primeau, F. & Variable, C. N: P stoichiometry of dissolved organic matter cycling in the Community Earth System Model. Biogeosciences 12, 209–221 (2015).

Li, X. et al. A high-resolution climate simulation dataset for the past 540 million years. Sci. Data 9, 1–10 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Spatial continuous modeling of early Cenozoic carbon cycle and climate. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11, nwae061 (2024).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Smith, R. et al. The Parallel Ocean Program (POP) Reference Manual: Ocean Component of the Community Climate System Model (CCSM) and Community Earth System Model (CESM). Los Alamos National Laboratory Rep. LAUR-01853 141, 1–140 (2010).

Smith, R. D. & McWilliams, J. C. Anisotropic horizontal viscosity for ocean models. Ocean Model. 5, 129–156 (2003).

Gent, P. R. & Mcwilliams, J. C. Isopycnal Mixing In Ocean Circulation Models. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 20, 150–155 (1990).

Liu, Y., Peltier, W., Yang, J. & Vettoretti, G. The initiation of Neoproterozoic “snowball” climates in CCSM3: the influence of paleocontinental configuration. Clim. Past 9, 2555–2577 (2013).

Large, W. G., McWilliams, J. C. & Doney, S. C. Oceanic vertical mixing: a review and a model with a nonlocal boundary layer parameterization. Rev. Geophys. 32, 363–403 (1994).

Baatsen, M. et al. The middle to late Eocene greenhouse climate modelled using the CESM 1.0. 5. Clim. Past 16, 2573–2597 (2020).

Moore, J. K., Doney, S. C., Kleypas, J. A., Glover, D. M. & Fung, I. Y. An intermediate complexity marine ecosystem model for the global domain. Deep Sea Res. Part II 49, 403–462 (2002).

Séférian, R. et al. Tracking improvement in simulated marine biogeochemistry between CMIP5 and CMIP6. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 6, 95–119 (2020).

Molina, E., Martínez, M., Sánchez, S., García, F. & Contreras, A. Growth and biochemical composition with emphasis on the fatty acids of Tetraselmis sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 36, 21–25 (1991).

Anderson, L. A. On the hydrogen and oxygen content of marine phytoplankton. Deep Sea Res. Part I 42, 1675–1680 (1995).

Sharoni, S. & Halevy, I. Geologic controls on phytoplankton elemental composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 119, e2113263118 (2022).

Penn, J. L., Deutsch, C., Payne, J. L. & Sperling, E. A. Temperature-dependent hypoxia explains biogeography and severity of end-Permian marine mass extinction. Science 362, eaat1327 (2018).

Bohlen, L., Dale, A. W. & Wallmann, K. Simple transfer functions for calculating benthic fixed nitrogen losses and C:N:P regeneration ratios in global biogeochemical models. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB3029 (2012).

Soetaert, K., Herman, P. M. & Middelburg, J. J. A model of early diagenetic processes from the shelf to abyssal depths. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 1019–1040 (1996).

Dunne, J. P., Sarmiento, J. L. & Gnanadesikan, A. A synthesis of global particle export from the surface ocean and cycling through the ocean interior and on the seafloor. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB4006 (2007).

Moore, J. K., Lindsay, K., Doney, S. C., Long, M. C. & Misumi, K. Marine Ecosystem Dynamics and Biogeochemical Cycling in the Community Earth System Model [CESM1(BGC)]: comparison of the 1990s with the 2090s under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 Scenarios. J. Clim. 26, 9291–9312 (2013).

Doney, S. C. et al. Mechanisms governing interannual variability in upper-ocean inorganic carbon system and air–sea CO2 fluxes: physical climate and atmospheric dust. Deep Sea Res. Part II 56, 640–655 (2009).

Long, M. C., Lindsay, K., Peacock, S., Moore, J. K. & Doney, S. C. Twentieth-century oceanic carbon uptake and storage in CESM1 (BGC). J. Clim. 26, 6775–6800 (2013).

Park, Y. et al. Emergence of the Southeast Asian islands as a driver for Neogene cooling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 25319–25326 (2020).

Zuo, H. et al. A revised model of global silicate weathering considering the influence of vegetation cover on erosion rate. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 3949–3974 (2024).

Gabet, E. J. & Mudd, S. M. A theoretical model coupling chemical weathering rates with denudation rates. Geology 37, 151–154 (2009).

Tang, M., Chu, X., Hao, J. & Shen, B. Orogenic quiescence in Earth’s middle age. Science 371, 728–731 (2021).

Morris, J. L. et al. The timescale of early land plant evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, E2274–E2283 (2018).

Gough, D. Solar interior structure and luminosity variations. Sol. Phys. 74, 21–34 (1981).

Liu, Y., Liu, P., Li, D., Peng, Y. & Hu, Y. Influence of dust on the initiation of Neoproterozoic snowball Earth events. J. Clim. 34, 6673–6689 (2021).

Jickells, T. et al. Global iron connections between desert dust, ocean biogeochemistry, and climate. Science 308, 67–71 (2005).

Solmon, F., Chuang, P., Meskhidze, N. & Chen, Y. Acidic processing of mineral dust iron by anthropogenic compounds over the north Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, D02305 (2009).

Hand, J. et al. Estimates of atmospheric-processed soluble iron from observations and a global mineral aerosol model: Biogeochemical implications. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D17205 (2004).

Kasting, J. & Walker, J. C. Limits on oxygen concentration in the prebiological atmosphere and the rate of abiotic fixation of nitrogen. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 86, 1147–1158 (1981).

Kasting, J. F. Stability of ammonia in the primitive terrestrial atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 87, 3091–3098 (1982).

Liu, P. et al. Triple oxygen isotope constraints on atmospheric O2 and biological productivity during the mid-Proterozoic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2105074118 (2021).

Mather, T. et al. Nitric acid from volcanoes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 218, 17–30 (2004).

Johnson, B. & Goldblatt, C. The nitrogen budget of Earth. Earth Sci. Rev. 148, 150–173 (2015).

Hartmann, J., Dürr, H. H., Moosdorf, N., Meybeck, M. & Kempe, S. The geochemical composition of the terrestrial surface (without soils) and comparison with the upper continental crust. Int. J. Earth Sci. 101, 365–376 (2012).

Watanabe, Y., Tajika, E. & Ozaki, K. Evolution of iron and oxygen biogeochemical cycles during the Precambrian. Geobiology 21, 689–707 (2023).

Hartmann, J., Moosdorf, N., Lauerwald, R., Hinderer, M. & West, A. J. Global chemical weathering and associated P-release—the role of lithology, temperature and soil properties. Chem. Geol. 363, 145–163 (2014).

Lucas, D. et al. Failure analysis of parameter-induced simulation crashes in climate models. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 1157–1171 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Y.L. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant 42225606. P.L is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant 42475052, the National Key Research and Development Program of China under grant 2024YFF0808000, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under grant 202541010, and Young Talent of Lifting Engineering for Science and Technology in Shandong, China under grant SDAST2024QTA022. S.L. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant 42121005. The simulations were performed on the High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University and the Marine Big Data Center of the Institute for Advanced Ocean Study of Ocean University of China. The authors thank the technical support of the National Large Scientific and Technological Infrastructure “Earth System Numerical Simulation Facility” (https://cstr.cn/31134.02.EL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. proposed the project. P.L. and Y.L. performed modeling analyses. P.L. and Y.L. wrote the manuscript. L.D., J.Z., S.L., and Y.C. contributed to the discussion and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Liu, Y., Dong, L. et al. Earth system simulations suggest that the Proterozoic ocean was greener but less productive. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69654-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69654-z