Abstract

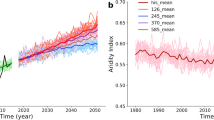

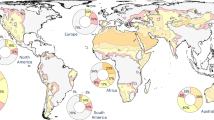

Drylands are highly vulnerable to global-scale aridity thresholds that cause drastic reductions in their productivity. While protected areas may help buffer against the impact of aridification, their effectiveness in mitigating the aridity thresholds across global drylands remains virtually unknown. Here we assembled a global dataset of drylands and found that highly protected areas, which include national parks and wilderness areas, can buffer the emergence of aridity thresholds in ecosystem productivity by up to 0.15 units of aridity. This suggests that, in highly protected regions, drylands must become substantially drier before reaching an aridity-induced threshold in ecosystem productivity. The importance of highly protected area for supporting drylands was consistent across 23 years of study, in woody and non-woody ecosystems and after accounting for rangelands. Notably, only 3.3% of all drylands were under The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) category I high levels of protection such as wilderness areas, with 3.8% being protected under IUCN category II (for example, national parks). Overall, our findings highlight the crucial role of highly protected areas in maintaining productive dryland ecosystem in the face of global aridity thresholds, and further stress the need for increasing the level of protection to ensure the conservation of drylands under predicted climate changes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the data used in this study are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29626661 (ref. 41).

Code availability

The R code used to analyse the data is available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29626736 (ref. 42).

References

Cherlet, M. et al. World Atlas of Desertification (Publication Office of the European Union, 2018).

Davies, J. et al. Conserving Dryland Biodiversity (IUCN, 2012).

Berdugo, M. et al. Global ecosystem thresholds driven by aridity. Science 367, 787–790 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Guirado, E., Gaitán, J. J. & Maestre, F. T. Aridity thresholds determine the relationships between ecosystem functioning and remotely sensed indicators across Patagonia. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–9 (2021).

Berdugo, M., Vidiella, B., Solé, R. V. & Maestre, F. T. Ecological mechanisms underlying aridity thresholds in global drylands. Funct. Ecol. 36, 4–23 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Water availability creates global thresholds in multidimensional soil biodiversity and functions. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1002–1011 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Dryland productivity under a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 981–994 (2022).

Moreno-Jiménez, E. et al. Aridity and reduced soil micronutrient availability in global drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2, 371–377 (2019).

Elsen, P. R., Monahan, W. B., Dougherty, E. R. & Merenlender, A. M. Keeping pace with climate change in global terrestrial protected areas. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay0814 (2020).

Rohde, M. M. et al. Groundwater-dependent ecosystem map exposes global dryland protection needs. Nature 632, 101–107 (2024).

de la Fuente, B., Weynants, M., Bertzky, B., Delli, G., Mandrici, A., Garcia Bendito, E. & Dubois, G. Land productivity dynamics in and around protected areas globally from 1999 to 2013. PLoS ONE 15, e0224958 (2020).

Didan, K. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250m SIN Grid V061 [Data set] (NASA, 2021).

García-Palacios, P., Gross, N., Gaitán, J. & Maestre, F. T. Climate mediates the biodiversity–ecosystem stability relationship globally. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8400–8405 (2018).

Bastin, J.-F. et al. The extent of forest in dryland biomes. Science 356, 635–638 (2017).

Gross, N. et al. Unforeseen plant phenotypic diversity in a dry and grazed world. Nature 632, 808–814 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Global evidence of positive biodiversity effects on spatial ecosystem stability in natural grasslands. Nat. Commun. 10, 3207 (2019).

Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2020).

Duncanson, L. et al. The effectiveness of global protected areas for climate change mitigation. Nat. Commun. 14, 2908 (2023).

Lewin, A., Murali, G. & Rachmilevitch, S. et al. Global evaluation of current and future threats to drylands and their vertebrate biodiversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1448–1458 (2024).

Huang, C., Asner, G. P., Barger, N. N., Neff, J. C. & Floyd, M. L. Regional aboveground live carbon losses due to drought-induced tree dieback in piñon–juniper ecosystems. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 1471–1479 (2010).

Abel, C., Maestre, F. T. & Berdugo, M. et al. Vegetation resistance to increasing aridity when crossing thresholds depends on local environmental conditions in global drylands. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 379 (2024).

Feldman, A. F., Konings, A. G. & Gentine, P. et al. Large global-scale vegetation sensitivity to daily rainfall variability. Nature 636, 380–384 (2024).

Maestre, F. T., Eldridge, D. J. & Soliveres et al. Structure and functioning of dryland ecosystems in a changing world. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 47, 215–237 (2016).

Durant, S. M., Becker, M. S. & Creel, S. et al. Developing fencing policies for dryland ecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 544–551 (2015).

Maestre, F. T. et al. The BIODESERT survey: assessing the impacts of grazing on the structure and functioning of global drylands. Web Ecol. 22, 75–96 (2022).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 195–213 (2002).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 19, 716–723 (1974).

Hastie, T. J. in Statistical models in S (ed. Hastie, T. J.) 249–307 (Routledge, 2017).

Mori, A. S. et al. Biodiversity–productivity relationships are key to nature-based climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 543–550 (2021).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database. Sci. Data 9, 409 (2022).

Friedl, M. & Sulla-Menashe, D. MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V061. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12Q1.061 (2022).

Sulla-Menashe, D. & Friedl, M. A. in User Guide to Collection 6 MODIS Land Cover (MCD12Q1 and MCD12C1) Product 1–18 (USGS, 2018).

Tsuchiya, K. IGBP (International Geosphere Biosphere Programme). J. Remote Sens. Soc. Jpn 14, 345–349 (1994).

Paruelo, J. M., Epstein, H. E., Lauenroth, W. K. & Burke, I. C. ANPP estimates from NDVI for the central grassland region of the United States. Ecology 78, 953–958 (1997).

Pérez-Hoyos, A. Global Crop and Rangeland Masks (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2018).

Fong, Y., Huang, Y., Gilbert, P. B. & Permar, S. R. chngpt: threshold regression model estimation and inference. BMC Bioinformatics 18, 454 (2017).

Hastie, T. & Hastie, M. T. Package ‘gam’. R package version 90124–3 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gam (2015).

Ghorbani, H. Mahalanobis distance and its application for detecting multivariate outliers. Facta Univ., Math. Inform. 34, 583–95 (2019).

ReHuffman, G. J., Stocker, E. F., Bolvin, D. T., Nelkin, E. J. & Tan, J. GPM IMERG Final Precipitation L3 Half Hourly 0.1 degree x 0.1 degree V07. GES DISC https://doi.org/10.5067/GPM/IMERG/3B-HH/07 (2024).

Kassambara, A. ggpubr. GitHub https://github.com/kassambara/ggpubr (2024).

Delgado-Baquerizo et al. Database of highly protected areas buffer against aridity thresholds in global drylands. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29626661 (2025).

Delgado-Baquerizo et al. Code of highly protected areas buffer against aridity thresholds in global drylands. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29626736 (2025).

Acknowledgements

M.D.-B. acknowledges support from a US Fulbright grant associated with the programme ‘Estancias de personal docente y/o investigador senior en centros extranjeros 2022’ from the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Spain (grant no. PRX22/00442). M.D.-B. also acknowledges support from GRASS4FUN (Biodiversa+ 2022)/MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ Unión Europea. D.J.E. is supported by the Hermon Slade Foundation. Y.F. is supported by the National Key R&D Program (grant no. 2024YFD1300800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.-B. conceived the original idea of the analyses presented in the Article. E.G. and M.D.-B curated and prepared the database. M.D.-B, E.G., Y.F. and J.Z. performed the statistical analyses and generated the figures. M.D.-B wrote the first draft. D.J.E., E.G., Y.F. and J.Z. contributed to data interpretation and paper editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Christin Abel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–23 and Tables 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Eldridge, D.J., Feng, Y. et al. Highly protected areas buffer against aridity thresholds in global drylands. Nat. Plants (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02099-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02099-2