Abstract

Skeletal muscle weakness is a major component of age-associated frailty, but the underlying mechanisms are not completely understood. Drosophila has emerged as a useful model for studying skeletal muscle aging. In this organism, previous lab-based selection established strains with increased longevity and reduced age-associated muscle functional decline compared to a parental strain. Here, we have applied a computational pipeline (JUMPptm) for retrieving information on 8 post-translational modifications (PTMs) from the skeletal muscle proteomes of 2 long-lived strains and the corresponding parental strain in young and old age. This pan-PTM analysis identified 2470 modified sites (acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, dihydroxylation, mono-methylation, oxidation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination) in several classes of proteins, including evolutionarily conserved muscle contractile proteins and metabolic enzymes. PTM consensus sequences further highlight the amino acids that are enriched adjacent to the modified site, thus providing insight into the flanking residues that influence distinct PTMs. Altogether, these analyses identify PTMs associated with muscle functional decline during aging and that may underlie the longevity and negligible functional senescence of lab-evolved Drosophila strains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The central dogma of biology posits that the information flows in a cell from the DNA to mRNA and ultimately to proteins1. Post-translational modifications of proteins (PTMs) have emerged as an additional layer of regulation of this information flow, with profound impacts on cellular identity and behavior2,3,4. However, a comprehensive understanding of PTMs in different physiologic and pathologic contexts is missing because routine pipelines for PTM identification require the experimental enrichment of modified peptides for a specific PTM5,6. Enrichment-free proteomic analyses also generate high-quality spectra corresponding to peptides with PTMs, based on their mass shift compared to the unmodified peptides. While this information is normally discarded, it was successfully used to identify multiple PTMs in different experimental contexts7,8,9. Recently, the JUMPptm pipeline10 was established to recover multiple PTMs from whole proteomes analyzed with JUMP11. In JUMPptm, a list of PTMs is provided as an input along with the whole proteome analysis results. Most interesting/abundant PTMs can be obtained using open searches such as MSFragger12 or by using literature searches, followed by a subsequent closed search for each PTM on high quality unmatched spectra with Comet13. Following the identification of modified peptides with maximal sensitivity, JUMPptm filters and quantifies the modified peptides10. With this approach, high-quality spectra corresponding to peptides with mass shifts are mapped to the corresponding known PTMs10. This pan-PTM analysis was previously used to identify PTMs associated with Alzheimer’s disease10 and determine the ubiquitin-modified proteome in cells with the knockdown of different ubiquitin-conjugation enzymes14.

Here, we utilized JUMPptm to determine the PTMs associated with age-related skeletal muscle dysfunction. Skeletal muscle aging is a major health issue and a co-morbidity of many age-related diseases15,16,17. Skeletal muscle function declines with aging also in Drosophila, and this organism has emerged as a useful model to investigate muscle aging18,19,20. Previously, we have found that fly strains with lab-evolved longevity (O1 and O3) display better muscle function with aging compared to the parental B3 strain21. These strains were obtained by exploiting the aging heterogeneity of a fly population: the longest-lived flies from an original group were selected and mated over multiple rounds, leading to the establishment of long-lived fly strains (O lines) with negligible functional senescence compared to the original B strain22,23. In particular, our previous analyses have established that the long-lived O1 and O3 strains have reduced rates of age-related defects in climbing, jumping, flight, and spontaneous locomotion, indicating an overall preservation of skeletal muscle function with aging in the O strains compared to the parental B line21. Importantly, these muscle functional deficits are present in the old B3 flies but not the young ones, indicating that muscle weakness is age-associated and not of developmental origin.

Studies in mice, Drosophila, and humans indicate that a collapse in protein quality control contributes to the decline in muscle function with aging18,24. In particular, a decline in the function of the autophagy/lysosome system and of protective proteases reduces proteostasis and impairs muscle function in Drosophila25,26,27,28,29,30 and mice 31,32,33,34. Consistent with these findings, analysis of proteostasis demonstrated that the long-lived O strains better maintain protein quality control during aging, as indicated by a lower amount of insoluble poly-ubiquitinated proteins, compared to the parental B strain21. Moreover, genome sequencing, RNA expression profiling, and deep-coverage TMT (tandem mass tag) mass spectrometry of thoracic skeletal muscles from these fly strains identified the molecular changes associated with the increased health span of O strains compared to the control B strain, including an increase in the levels of the circadian regulator timeless21.

While these analyses have provided remarkable insight into the molecular basis for the extreme variation in lifespan and functional decay with aging, there are likely additional layers of complexity that underlie the evolution of longevity in the O strains. In particular, in addition to changes in protein levels, the localization, activity, and stability of proteins can be remodeled by post-translational modifications (PTMs) that constitute a complex code to reshape the proteome in physiological and pathological contexts2,3,4. Here, we have utilized JUMPptm to retrieve PTMs from whole proteome data. By applying this approach to the TMT mass spectrometry analysis of the skeletal muscles of young and old B3, O1, and O3 lines, we identify PTMs associated with the preservation of skeletal muscle function during aging in Drosophila. Because many of these PTMs occur in evolutionarily conserved proteins, this analysis may be relevant for better understanding the mechanisms of age-associated skeletal muscle dysfunction in humans.

Results

Identification of PTMs associated with lab-evolved negligible muscle functional senescence

We applied the JUMPptm pipeline to identify post-translational modifications (PTMs) from the TMT mass spectrometry data obtained from thoracic skeletal muscles from long-lived flies that are protected from age-related skeletal muscle dysfunction (O1 and O3 strains) and the corresponding parental line (B3) in young age (1-week-old) and old age (6-week-old)21. The initial TMT analyses consisted of 2 batches of 10-plex TMT data that were combined via a common reference sample that was included in both TMT sets (Fig. 1a). Global TMT data normalization ensured that a similar average protein abundance was present across the 2 TMT data sets (Fig. 1b). JUMPptm was utilized to search 8 different PTMs selected based on abundance (open PTM guided search) and based on interest, namely acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, dihydroxylation, mono-methylation, oxidation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. The results were further filtered to include only PTMs that are cross-shared across all samples and TMT batches. Collectively, these analyses retrieved 2470 modified peptides from 442 proteins encoded by 411 genes (Supplementary Data 1). Principal component analysis (PCA) of the PTMs retrieved by JUMPptm indicates that the B3 datasets are remarkably different from the O1 and O3 datasets and that the difference between young vs. old samples is more pronounced for skeletal muscle from the B strain compared to the O strains (Fig. 1c), which presumably reflects the age-related decline in muscle function that occurs in B but less so in O flies21.

a TMT mass spectrometry data from skeletal muscles were previously obtained from the thoracic skeletal muscle of young (1 week) and old (6 weeks) B3, O1, and O3 Drosophila strains. O1 and O3 are long-lived flies that display minimal age-related skeletal muscle dysfunction compared to the parental B3 strain from which they were obtained after multiple rounds of selection. b A common reference sample was utilized for the normalization and integration of 2 TMT sets. c PCA analysis of the 2470 modified peptides retrieved with JUMPptm, which was utilized to identify acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, dihydroxylation, mono-methylation, oxidation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. See also Supplementary Data 1. d, e Overlap between the JUMPptm results and the large and small genetic variants (reported in ref. 21) that distinguish the O1/O3 strains from the B line. There is minimal overlap (i.e., 3/411) between the large genomic variants and the 411 genes that encode for the 442 proteins with the JUMPptm-detected modified peptides (d). A larger overlap (i.e., 59/411) is present in the comparison to the small genetic variants (e).

In our previous study21, we examined the genomic changes that evolved in the O1 and O3 lines and that differentiate them from the parental B3 line: these analyses identified large and small genomic variants that differentiate the O vs. B strains21. On this basis, we next examined to what extent genomic variants target the same proteins that carry PTMs (identified with JUMPptm). Cross-comparison indicates that PTMs primarily occur in proteins that are not affected by large and small genetic variants (Fig. 1d, e and Source Data), indicating that PTMs are an additional layer of phenotypic evolution of the O strains from the B strain,

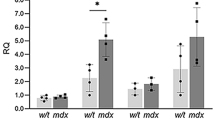

PTMs that distinguish long-lived O strains from the parental B line do not merely oppose age-associated changes

We then examined the prevalence of PTMs that are significantly regulated (adjusted P < 0.05) and that are cross-shared in different genotype-age comparisons (Fig. 2a): these analyses indicate that the highest number of significantly regulated PTMs is cross-shared by O1 vs. B3 and O3 vs. B3 at both 1 and 6 weeks (Fig. 2a). A similar pattern is also found when examining individual PTMs: also in this case, the major differences between O and B strains are constitutive, i.e. present in both young and old age (Fig. 2b, c). However, a closer analysis indicates that the number of significantly regulated PTMs in O vs. B increases with aging (e.g., six-week O3 vs. B3 compared to 1-week O3 vs. B3). While this increase is moderate for acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, mono-methylation, and oxidation, it is substantially more marked for dihydroxylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (Fig. 2b, c), suggesting that these modifications are more closely related to the differential changes in skeletal muscle function that occur with aging in O vs. B strains. On the other hand, relatively few PTMs were significantly modulated by aging in each strain (e.g., B3 old vs. young), (Fig. 2b, c), suggesting that muscle functional decline is divergently regulated in O and B strains by PTMs that do not merely oppose age-related changes.

a Overview of the peptides with post-translational modifications (PTMs) that are significantly modulated (adjusted P-value < 0.05) in at least one age-genotype comparison. The significantly regulated PTMs are indicated for the cross-comparisons across groups. For example, the first vertical column indicates the number of significantly modulated PTMs that are cross-shared by the 4 last-listed age/genotype comparisons; the horizontal columns indicate the significantly modulated PTMs that are found in each age/genotype comparison. b, c Additional analyses indicate the differential abundance of PTMs and how they are modulated in O vs. B and old vs. young comparisons. The results for acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, dihydroxylation, mono-methylation, oxidation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination are indicated (adjusted P-value < 0.05).

Analysis of the modified peptides that are most strikingly regulated (adjusted P < 0.05) indicates the predominance of deamidation (n = 319) and oxidative modifications (n = 115) (Fig. 3), consistent with the known pervasiveness of these PTMs during aging in multiple systems35,36,37. These modifications can have a profound impact on protein function but largely arise from spontaneous non-enzymatic reactions that target susceptible proteins38,39,40,41. There were overall fewer significantly modulated peptides with PTMs that arise from enzymatic reactions and that are more tightly associated with signaling42,43,44,45,46: protein mono-methylation (n = 71), acetylation (n = 49), dihydroxylation (n = 44), carboxylation (n = 40), phosphorylation (n = 34), and ubiquitination (n = 4) (Fig. 3).

a–h Comparison of the peptides with post-translational modifications (PTMs) that are significantly modulated (adjusted P-value < 0.05) in at least one age-genotype comparison. The significantly regulated PTMs are indicated for the cross-comparisons across groups. The vertical columns indicate the number of significantly modulated PTMs that are cross-shared by multiple age/genotype comparisons; the horizontal columns indicate the significantly modulated PTMs that are found in each age/genotype comparison. The results for acetylation (a), carboxylation (b), deamidation (c), dihydroxylation (d), mono-methylation (e), oxidation (f), and phosphorylation (g) are shown. Only n = 4 peptides with ubiquitination are modulated with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 (h).

Volcano plots representing the peptides with PTMs further highlight this trend: there are relatively few significant PTMs that are modulated with aging in each strain (Fig. 4a–c), whereas multiple PTMs are significantly downregulated and upregulated in O1 versus B3 and O3 versus B3 in both young and old age (Fig. 4d–g). Altogether, these analyses reveal profound remodeling of PTMs in response to lab-evolved negligible senescence.

a–g Volcano plots of the PTMs that are significantly modulated by aging within each strain (a–c) and in O vs. B comparisons in young (d, e) and old age (f, g). Each graph displays the log2FC on the x-axis and the -log10(adj. P-value) on the y-axis. PTMs that are modulated with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 and log2FC > |1| are displayed as full dots. PTMs that do not meet these criteria are shown as empty dots. Protein names and modified sites are indicated for the significantly modulated PTMs in each comparison. Each PTM type is color-coded.

Age-regulated PTMs that differ in O vs. B strains impact muscle contractile proteins and metabolic enzymes

We next evaluated the enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with the significantly regulated PTMs at 1 week in O versus B, identifying GO terms that were overrepresented. Enriched categories in O3 vs. B3 included glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, muscle contraction, actin binding, tryptophan metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, cytoskeleton, tricarboxylic acid cycle, microtubule, PDZ domains, and calcium ion binding (Fig. 5a). Analysis in old age highlighted a few additional categories (protein folding, stress response, and ATP binding) whereas the top-regulated category consisted of “muscle thin filament assembly” (Fig. 5b). Substantially similar categories were also differentially enriched in O1 vs. B3 at both ages.

a, b GO term analysis of the proteins with PTMs that are significantly modulated (P < 0.05) in O3 vs. B3 in young (a) and old age (b). The -log10(P-value) and count is indicated. c, d Cross-shared PTMs that are significantly modulated by aging in B3, O1, and O3 include modifications of sarcomeric proteins and regulators of metabolism (c), as indicated by the GO term analysis (d). In (c), significantly modulated proteins (P < 0.05) are highlighted in bold green fonts whereas the numerical values refer to the log2FC (downregulation is shown in blue, upregulation is shown in red).

The modified proteins included many evolutionary conserved regulators (Fig. 5c, d), including ND-B8 and ND-13A (components of the mitochondrial complex I), the PMPCA homolog CG8728 (a peptidase necessary for the proteolytic processing of proteins targeted to the mitochondrion), and EfTuM/mEFTu1 (mitochondrial translation elongation factor Tu 1). Metabolic enzymes included the fructose-bisphosphate aldolase Ald1, the hexokinase Hex-A, the citrate synthase kdn/Cs1, the malate dehydrogenase Mdh2, the glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase Gapdh1, the glutamate dehydrogenase Gdh, and the delta-1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase P5CDh1 (involved in proline degradation). Moreover, many sarcomeric components are modulated, including myosin heavy chain (Mhc) and other components of myosin thick filaments, i.e. bent (bt), flightin (fln), myofilin (Mf), myosin alkali light chain 1 (Mlc1) as well as actin-binding proteins (supervillin, Svil) and proteins involved in sarcomere organization (mask, Zasp52, and Zasp66), (Fig. 5c, d).

Collectively, 38 PTMs (acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, mono-methylation, and oxidation) were cross-shared in 27 proteins primarily involved in metabolism and sarcomere organization (Fig. 5c, d). While some PTMs were discordantly regulated in O1 vs. B3 compared to O3 vs. B3, others were consistently regulated by O1 and O3 compared to B3. For example, Argk deamidation at N179 increases with aging in the B3 strain but less so in the O strains, whereas mono-methylation of mask at K3119 decreases with aging in the B3 strain but less so in the O strains.

Other PTMs are conversely regulated with aging in the muscle of the B3 vs. O strains. There is age-downregulation in B3 but an upregulation in O1 and/or O3 of P84,D85 oxidation of the mitochondrial complex I component ND-B8, K337 carboxylation of CG31064, Q126 deamidation of the sarcomeric protein fln, and S384 and K385 acetylation of myosin heavy chain (Mhc). Conversely, Gdh deamination at N386 and its oxidation at D167 increase with aging in B3 but decline in O1 and O3 (Fig. 5c).

Collectively, cross-shared PTMs that are inversely regulated by aging in O vs. B strains may contribute to preserving skeletal muscle function during aging.

Analysis of modified peptides identified with JUMPptm defines PTM consensus sequences

While many PTMs are known to be age-modulated, it is largely underexplored whether there are structural determinants that modulate such PTMs. In particular, it remains only partially explored whether specific flanking amino acids influence the modification at specific sites. This is a recognized gap in knowledge especially for spontaneous, non-enzymatic PTMs such as deamidation36,37,38,39,40,41. On this basis, we have examined the amino acid residues that are adjacent to the modified site. To this purpose, we utilized iceLogo47,48 to visualize the consensus pattern in modified peptides. The Drosophila melanogaster proteome was used as the reference dataset. With this analysis, we have defined the consensus sequence for acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, dihydroxylation, mono-methylation, oxidation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (Fig. 6). Specifically, in addition to the expected modified sites, we identify flanking amino acids (from −7 to +7) that are significantly enriched or depleted and that, therefore, may influence the susceptibility to a specific PTM (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2). For example, we find that acetylation sites are flanked by K residues at +1 and −1 (Fig. 6a), that carboxylated amino acids display Y residues at +1 and −1 (Fig. 6b), and that deamidation preferentially has a G residue in the +1 position (Fig. 6c). Interestingly, oxidation is preferentially associated with the presence of W amino acids at the −1 and +1 positions and, to a lower extent, at positions −2 and +2 (Fig. 6f). Phosphorylation (Fig. 6g) and dihydroxylation (Fig. 6d) are flanked by a P at the +1 position. Overall, consensus sequence analysis for the PTMs retrieved via JUMPptm identifies flanking amino acids that are enriched (or depleted) and that may play a role in determining the susceptibility of a specific amino acid residue to undergo a PTM.

Consensus sites (obtained with iceLogo) for acetylation (a), carboxylation (b), deamidation (c), dihydroxylation (d), mono-methylation (e), oxidation (f), phosphorylation (g), and ubiquitination (h). The frequency of modified and flanking amino acids is indicated. Only significantly (P < 0.05) enriched (positive values) and depleted (negative values) amino acids are shown for positions −7 to +7 relative to the modified amino acid. See also Supplementary Data 2.

Discussion

Lab-evolved models and analysis of natural variation in lifespan and age-related traits have provided remarkable insight into the mechanisms that govern aging in Drosophila and other organisms49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. While most studies have focused on the analysis of genetic traits (i.e., gene variants and gene expression), there is a growing interest in defining other features of long-lived strains. Previous studies with the O1 and O3 strains have defined genomic, transcriptional, proteomic, and metabolic changes that differentiate them from the parental B3 strain21,22,23,55,58. Moreover, a thorough characterization of motor function has revealed remarkable preservation of skeletal muscle function in the O strains compared to the parental B strain21. Here, we report an additional dataset that provides insight into the remarkable health span of O lines. Specifically, we utilized the JUMPptm pipeline10 to recover PTMs associated with protection from age-related muscle dysfunction (Fig. 1). Our analyses pinpoint PTMs that are differentially modulated in O vs. B lines, including some that are also modulated during normal aging (Figs. 2–4). The modified peptides map to metabolic enzymes and proteins of the muscle contractile apparatus that are evolutionarily well conserved, thus providing insight relevant also to muscle aging in higher organisms. The modified proteins include myosin heavy chain (Mhc), which is known to be modulated by post-translational modifications in both Drosophila and humans59,60. Specifically, PTMs that occur during aging were previously found to reduce Mhc function (e.g., myosin ATPase and myosin filament formation)59,60 and hence are likely to contribute to the age-associated decline in muscle force production.

In addition to defects in the organization and function of muscle contractile proteins61,62,63,64, muscle functional decline with aging is characterized by a reduction in mitochondrial metabolic capacity65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72, which results at least in part from defects in the assembly of the complexes of the electron transport chain73,74,75,76,77. Interestingly, mitochondrial function declines before an overt decline in myofiber size and the ensuing muscle wasting78, suggesting that it is an early event of muscle aging that occurs in humans as in model organisms18. In this context, it is interesting to note that ND-B8 and ND-13A (components of the mitochondrial complex I) are differentially oxidized in the O strains vs. B3 (Fig. 5c), suggesting that this may regulate the assembly or stability of complex I. Altogether, the PTM analysis of lab-evolved strains pinpoints a multi-pronged adaptation that sustains motor function in the O strains during aging. Specifically, post-translational modifications represent an additional layer of complexity that differentiates the strains with negligible functional senescence from the original parental line from which they were selected.

In addition to defining molecular markers of skeletal muscle aging, our PTM analyses provide a useful resource that could help better understand the sequence and structural determinants that make proteins susceptible to spontaneous and enzymatic post-translational modifications. For example, deamidation of asparagine and glutamine residues is frequently observed during aging and results from a spontaneous reaction that has been proposed to represent a molecular clock of aging36,37,38,39,40,41. However, the rules that make certain asparagine and glutamine residues prone to deamidation remain incompletely understood. Presumably, the propensity of different amino acids for deamidation depends not only on their location within a protein but also on the specific cellular environment. In line with this scenario, we have defined the consensus sequences for each PTM by identifying amino acids that are enriched in the positions flanking the modified site (Fig. 6). Based on our analysis, a flanking G residue in position +1 is significantly associated with deamidation (Fig. 6c).

Altogether, our data on 8 common PTMs and their associations with lifespan and muscle function provide a useful reference dataset for defining the overarching principles that govern the susceptibility to post-translational modifications. While the consensus sequences were defined in the context of Drosophila muscle aging, future studies should determine whether they are universal or rather influenced by the age, sex, and tissue considered.

A limitation of this study is that we did not identify all PTMs that likely occur across multiple proteins due to the sensitivity limitation of TMT mass spectrometry and JUMPptm. Therefore, while our original study identified an important role of timeless and the muscle circadian clock in the difference between O vs. B strains21, we did not detect any PTMs occurring in any core components of the circadian cycle. Likewise, although protein quality control is key for muscle function and aging25,26,79,80,81, we did not detect PTMs in components of the proteostasis network.

While our studies focused on skeletal muscle, it is important to note that muscle dysfunction is a key determinant of organismal aging and lifespan17. In humans, grip strength and muscle function are predictors of mortality from all causes82,83,84. In Drosophila and other model organisms, activation of pro-longevity pathways specifically in skeletal muscles extends lifespan and can impede the age-associated decline in proteostasis and function of other tissues19,24,26,27,28,29,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95. For example, activation of a moderate stress response in skeletal muscle (e.g., the proteasome stress response96) induces protective systemic signaling (mediated by the amylase Amyrel, the disaccharide maltose, and the SLC45 maltose transporters) that preserves protein quality control in the brain and retina during aging88. Therefore, it is possible that PTMs that are associated with the differential muscle aging of O vs. B lines also have an impact on organismal aging and lifespan.

In summary, this study provides a reference dataset to understand the role of PTMs in skeletal muscle aging, which is important for systemic aging. Because many of the PTMs detected here occur in evolutionarily conserved proteins, these findings obtained from Drosophila may prove relevant for better understanding the etiology of sarcopenia in humans.

Methods

Experimental Drosophila model of lab-evolved negligible senescence

The Drosophila melanogaster strains experimentally selected for delayed senescence (O1 and O3) and the parental B3 strain were previously described21,22,23,55,58. The TMT datasets were obtained from the thoraces (which consist primarily of skeletal muscle) from B3, O1, O3 flies at the ages of 1 and 6 weeks, as previously reported21.

JUMPptm identification and statistical analysis of differentially expressed peptides with PTMs

The JUMPptm search10 was conducted on the TMT proteome datasets that we previously described21 and that are available at the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository under accession number PXD014223. High-quality unmatched spectra with de novo tags obtained post-JUMP search for each batch were utilized as input for JUMPptm, as previously described10. This input was searched for 8 PTMs (acetylation, carboxylation, deamidation, dihydroxylation, mono-methylation, oxidation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination) using a multi-stage database search strategy. The resulting peptides with PTMs were quantified using the TMT-based quantification function of the JUMP software suite11.

Post-translationally modified peptides identified in both experimental batches (i.e., in the 2 TMT sets) were combined, and only the peptides consistently detected in both batches were retained for subsequent analysis. The resulting dataset was globally normalized by using the internal reference and median value from each batch, followed by mean centering across samples. Differentially expressed peptides with PTMs were identified using the limma package in R Studio97. The P-values were computed using the Empirical Bayes (eBayes) method, and the false discovery rate (FDR) values were determined using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

The JUMPptm results are reported in Supplementary Data 1, which includes Supplementary Tables 1–4, as explained below.

Supplementary Table 1 reports the meta information about the sample and proteomics batches.

Supplementary Table 2 reports the mass spectrometry results from two batches after JUMPptm search. This represents the common proteins identified in both batches. All abundance values are presented in log2 scale.

Supplementary Table 3 reports the protein data matrix from Supplementary Table 2 after normalization. Normalization was done using the internal reference channel and median value of the batch, followed by mean centering across samples. This output of normalization was the input of PCA analysis and DEP analysis.

Supplementary Table 4 reports the statistical analysis of PTMs. Differentially expressed PTMs were identified using the limma package. Columns with logFC extension represent the log2 fold change between the comparison. Columns with P.Value extension represent the P-value, and adj.P.Val represents the false discovery controlled value.

Comparison of genomic variants to PTMs

For the overlap between genomic variants and the JUMP-PTM gene sets, unique and shared genes were identified using set operations and Venn diagrams were generated to visualize the overlap using the matplotlib-venn library (https://github.com/konstantint/matplotlib-venn).

Generation of PTM consensus sequences and amino acid sequence logos

To analyze amino acid preferences surrounding post-translational modifications (PTMs), we utilized iceLogo47,48. The reference set was a precompiled Swiss-Prot composition of Drosophila melanogaster. A “scoring system of percentage” was used, and a P-value of 0.05 was used as a cutoff to visualize IceLogo. The input file consisted of a collection of 15 aa long sequences, with the center being the modified amino acid (Supplementary Data 2).

Data organization and scientific graphing

Data organization and scientific graphing were done with Excel, Rstudio (version 2024.04.2+764), and Srplot (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/srplot). The UpSet graphs representing PTM types were plotted with the ComplexHeatmap package98,99. PCA were plotted using ClustVis100. The graphs in Figs. 2 and 3 are based on PTMs with adjusted P-value < 0.05. Graphs in Fig. 5 are based on PTMs that are significantly modulated with P < 0.05.

Data availability

The JUMPptm results are reported in Supplementary Data 1. The PTM consensus sequences are reported in Supplementary Data 2. Additional data are provided in the Source Data file.

References

Quake, S. R. The cellular dogma. Cell 187, 6421–6423 (2024).

Keenan, E. K., Zachman, D. K. & Hirschey, M. D. Discovering the landscape of protein modifications. Mol. Cell 81, 1868–1878 (2021).

Lee, J. M., Hammaren, H. M., Savitski, M. M. & Baek, S. H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 14, 201 (2023).

Suskiewicz, M. J. The logic of protein post-translational modifications (PTMs): Chemistry, mechanisms and evolution of protein regulation through covalent attachments. Bioessays 46, e2300178 (2024).

Zhao, Y. & Jensen, O. N. Modification-specific proteomics: strategies for characterization of post-translational modifications using enrichment techniques. Proteomics 9, 4632–4641 (2009).

Macek, B., Mann, M. & Olsen, J. V. Global and site-specific quantitative phosphoproteomics: principles and applications. Annu. Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 49, 199–221 (2009).

Chick, J. M. et al. A mass-tolerant database search identifies a large proportion of unassigned spectra in shotgun proteomics as modified peptides. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 743–749 (2015).

Devabhaktuni, A. et al. TagGraph reveals vast protein modification landscapes from large tandem mass spectrometry datasets. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 469–479 (2019).

Solntsev, S. K., Shortreed, M. R., Frey, B. L. & Smith, L. M. Enhanced Global Post-translational Modification Discovery with MetaMorpheus. J. Proteome Res. 17, 1844–1851 (2018).

Poudel, S. et al. JUMPptm: Integrated software for sensitive identification of post-translational modifications and its application in Alzheimer’s disease study. Proteomics, e2100369, https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.202100369 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. JUMP: a tag-based database search tool for peptide identification with high sensitivity and accuracy. Mol. Cell Proteom. 13, 3663–3673 (2014).

Kong, A. T., Leprevost, F. V., Avtonomov, D. M., Mellacheruvu, D. & Nesvizhskii, A. I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Methods 14, 513–520 (2017).

Eng, J. K., Jahan, T. A. & Hoopmann, M. R. Comet: an open-source MS/MS sequence database search tool. Proteomics 13, 22–24 (2013).

Hunt, L. C. et al. An adaptive stress response that confers cellular resilience to decreased ubiquitination. Nat. Commun. 14, 7348 (2023).

Brooks, S. V. & Faulkner, J. A. Skeletal muscle weakness in old age: underlying mechanisms. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 26, 432–439 (1994).

Goodpaster, B. H. et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 1059–1064 (2006).

Nair, K. S. Aging muscle. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 953–963 (2005).

Demontis, F., Piccirillo, R., Goldberg, A. L. & Perrimon, N. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle aging: insights from Drosophila and mammalian models. Dis. Model Mech. 6, 1339–1352 (2013).

Demontis, F., Piccirillo, R., Goldberg, A. L. & Perrimon, N. The influence of skeletal muscle on systemic aging and lifespan. Aging Cell 12, 943–949 (2013).

Piccirillo, R., Demontis, F., Perrimon, N. & Goldberg, A. L. Mechanisms of muscle growth and atrophy in mammals and Drosophila. Dev. Dyn. 243, 201–215 (2014).

Hunt, L. C. et al. Circadian gene variants and the skeletal muscle circadian clock contribute to the evolutionary divergence in longevity across Drosophila populations. Genome Res. 29, 1262–1276 (2019).

Rose, M. R. Laboratory Evolution of Postponed Senescence in Drosophila Melanogaster. Evolution 38, 1004–1010 (1984).

Rose, M. R. & Graves, J. L. Jr What evolutionary biology can do for gerontology. J. Gerontol. 44, B27–B29 (1989).

Jiao, J. & Demontis, F. Skeletal muscle autophagy and its role in sarcopenia and organismal aging. Curr. Opin. Pharm. 34, 1–6 (2017).

Arndt, V. et al. Chaperone-Assisted Selective Autophagy Is Essential for Muscle Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 20, 143–148 (2010).

Bai, H., Kang, P., Hernandez, A. M. & Tatar, M. Activin signaling targeted by insulin/dFOXO regulates aging and muscle proteostasis in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003941 (2013).

Demontis, F. & Perrimon, N. FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell 143, 813–825 (2010).

Jiao, J. et al. Modulation of protease expression by the transcription factor Ptx1/PITX regulates protein quality control during aging. Cell Rep. 42, 111970 (2023).

Hunt, L. C. et al. Antagonistic control of myofiber size and muscle protein quality control by the ubiquitin ligase UBR4 during aging. Nat. Commun. 12, 1418 (2021).

Ulgherait, M., Rana, A., Rera, M., Graniel, J. & Walker, D. W. AMPK modulates tissue and organismal aging in a non-cell-autonomous manner. Cell Rep. 8, 1767–1780 (2014).

Carnio, S. et al. Autophagy impairment in muscle induces neuromuscular junction degeneration and precocious aging. Cell Rep. 8, 1509–1521 (2014).

Castets, P. et al. Sustained activation of mTORC1 in skeletal muscle inhibits constitutive and starvation-induced autophagy and causes a severe, late-onset myopathy. Cell Metab. 17, 731–744 (2013).

Garcia-Prat, L. et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature 529, 37–42 (2016).

Masiero, E. et al. Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab. 10, 507–515 (2009).

Reeg, S. & Grune, T. Protein Oxidation in Aging: Does It Play a Role in Aging Progression? Antioxid. Redox Signal 23, 239–255 (2015).

Hains, P. G. & Truscott, R. J. Age-dependent deamidation of lifelong proteins in the human lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 3107–3114 (2010).

Robinson, N. E. & Robinson, A. B. Deamidation of human proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12409–12413 (2001).

Wijerathne, D. V., Karabulut, S. & Gauld, J. W. Computational Insights into Protein Aging: Spontaneous Deamidation of Glutamine. J. Phys. Chem. B 128, 5545–5556 (2024).

Norton-Baker, B. et al. Deamidation of the human eye lens protein gammaS-crystallin accelerates oxidative aging. Structure 30, 763–776.e764 (2022).

Nguyen, P. T., Zottig, X., Sebastiao, M. & Bourgault, S. Role of Site-Specific Asparagine Deamidation in Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Amyloidogenesis: Key Contributions of Residues 14 and 21. Biochemistry 56, 3808–3817 (2017).

Takata, T., Oxford, J. T., Demeler, B. & Lampi, K. J. Deamidation destabilizes and triggers aggregation of a lens protein, betaA3-crystallin. Protein Sci. 17, 1565–1575 (2008).

Tie, J. K. et al. Characterization of vitamin K-dependent carboxylase mutations that cause bleeding and nonbleeding disorders. Blood 127, 1847–1855 (2016).

Lacombe, J. et al. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation regulates Ca(2+) flux and adaptation to metabolic stress in beta cells. Cell Rep. 42, 112500 (2023).

Barnes, M. J., Constable, B. J., Morton, L. F. & Royce, P. M. Age-related variations in hydroxylation of lysine and proline in collagen. Biochem. J. 139, 461–468 (1974).

Clarke, S. Aging as war between chemical and biochemical processes: protein methylation and the recognition of age-damaged proteins for repair. Ageing Res. Rev. 2, 263–285 (2003).

Liu, R. et al. Methylation across the central dogma in health and diseases: new therapeutic strategies. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 310 (2023).

Colaert, N., Helsens, K., Martens, L., Vandekerckhove, J. & Gevaert, K. Improved visualization of protein consensus sequences by iceLogo. Nat. Methods 6, 786–787 (2009).

Maddelein, D. et al. The iceLogo web server and SOAP service for determining protein consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W543–W546 (2015).

Barzilai, N. et al. The place of genetics in ageing research. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 589–594 (2012).

Milman, S. & Barzilai, N. Dissecting the Mechanisms Underlying Unusually Successful Human Health Span and Life Span. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a025098 (2015).

Carbone, M. A. et al. Genetic architecture of natural variation in visual senescence in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6620–E6629 (2016).

Geiger-Thornsberry, G. L. & Mackay, T. F. Quantitative trait loci affecting natural variation in Drosophila longevity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 125, 179–189 (2004).

Lai, C. Q., Parnell, L. D., Lyman, R. F., Ordovas, J. M. & Mackay, T. F. Candidate genes affecting Drosophila life span identified by integrating microarray gene expression analysis and QTL mapping. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128, 237–249 (2007).

Mackay, T. F. The nature of quantitative genetic variation for Drosophila longevity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 123, 95–104 (2002).

Wilson, R. H., Morgan, T. J. & Mackay, T. F. High-resolution mapping of quantitative trait loci affecting increased life span in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 173, 1455–1463 (2006).

Arking, R. Gene expression and regulation in the extended longevity phenotypes of Drosophila. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 928, 157–167 (2001).

Sujkowski, A., Bazzell, B., Carpenter, K., Arking, R. & Wessells, R. J. Endurance exercise and selective breeding for longevity extend Drosophila healthspan by overlapping mechanisms. Aging 7, 535–552 (2015).

Parkhitko, A. A. et al. Tissue-specific down-regulation of S-adenosyl-homocysteine via suppression of dAhcyL1/dAhcyL2 extends health span and life span in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 30, 1409–1422 (2016).

Neal, C. L. et al. Aging-affiliated post-translational modifications of skeletal muscle myosin affect biochemical properties, myofibril structure, muscle function, and proteostasis. Aging Cell 23, e14134 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Aberrant post-translational modifications compromise human myosin motor function in old age. Aging Cell 14, 228–235 (2015).

Prochniewicz, E., Thompson, L. V. & Thomas, D. D. Age-related decline in actomyosin structure and function. Exp. Gerontol. 42, 931–938 (2007).

Hook, P., Sriramoju, V. & Larsson, L. Effects of aging on actin sliding speed on myosin from single skeletal muscle cells of mice, rats, and humans. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C782–C788 (2001).

Lowe, D. A., Surek, J. T., Thomas, D. D. & Thompson, L. V. Electron paramagnetic resonance reveals age-related myosin structural changes in rat skeletal muscle fibers. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C540–C547 (2001).

Larsson, L., Li, X. & Frontera, W. R. Effects of aging on shortening velocity and myosin isoform composition in single human skeletal muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 272, C638–C649 (1997).

Johnson, M. L., Robinson, M. M. & Nair, K. S. Skeletal muscle aging and the mitochondrion. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 24, 247–256 (2013).

Chabi, B. et al. Mitochondrial function and apoptotic susceptibility in aging skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 7, 2–12 (2008).

Gouspillou, G. et al. Alteration of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in aged skeletal muscle involves modification of adenine nucleotide translocator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 143–151 (2010).

Ljubicic, V. et al. Molecular basis for an attenuated mitochondrial adaptive plasticity in aged skeletal muscle. Aging 1, 818–830 (2009).

Mansouri, A. et al. Alterations in mitochondrial function, hydrogen peroxide release and oxidative damage in mouse hind-limb skeletal muscle during aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 127, 298–306 (2006).

Melov, S., Shoffner, J. M., Kaufman, A. & Wallace, D. C. Marked increase in the number and variety of mitochondrial DNA rearrangements in aging human skeletal muscle. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 4122–4126 (1995).

Petersen, K. F. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science 300, 1140–1142 (2003).

Short, K. R. et al. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5618–5623 (2005).

Hossain, K. F. B., Murari, A., Mishra, B. & Owusu-Ansah, E. The membrane domain of respiratory complex I accumulates during muscle aging in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 12, 22433 (2022).

Kruse, S. E. et al. Age modifies respiratory complex I and protein homeostasis in a muscle type-specific manner. Aging Cell 15, 89–99 (2016).

Boffoli, D. et al. Decline with age of the respiratory chain activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1226, 73–82 (1994).

Ferguson, M., Mockett, R. J., Shen, Y., Orr, W. C. & Sohal, R. S. Age-associated decline in mitochondrial respiration and electron transport in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. J. 390, 501–511 (2005).

Walker, D. W. & Benzer, S. Mitochondrial “swirls” induced by oxygen stress and in the Drosophila mutant hyperswirl. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10290–10295 (2004).

Ibebunjo, C. et al. Genomic and proteomic profiling reveals reduced mitochondrial function and disruption of the neuromuscular junction driving rat sarcopenia. Mol. Cell Biol. 33, 194–212 (2013).

Curley, M. et al. Transgenic sensors reveal compartment-specific effects of aggregation-prone proteins on subcellular proteostasis during aging. Cell Rep. Methods, 100875, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2024.100875 (2024).

Brooks, D. et al. Drosophila NUAK functions with Starvin/BAG3 in autophagic protein turnover. PLoS Genet 16, e1008700 (2020).

Guo, Y., Zeng, Q., Brooks, D. & Geisbrecht, E. R. A conserved STRIPAK complex is required for autophagy in muscle tissue. Mol. Biol. Cell 34, ar91 (2023).

Metter, E. J. et al. Muscle quality and age: cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 54, B207–B218 (1999).

Metter, E. J., Talbot, L. A., Schrager, M. & Conwit, R. Skeletal muscle strength as a predictor of all-cause mortality in healthy men. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 57, B359–B365 (2002).

Swindell, W. R. et al. Indicators of “healthy aging” in older women (65-69 years of age). A data-mining approach based on prediction of long-term survival. BMC Geriatr. 10, 55 (2010).

Demontis, F., Patel, V. K., Swindell, W. R. & Perrimon, N. Intertissue control of the nucleolus via a myokine-dependent longevity pathway. Cell Rep. 7, 1481–1494 (2014).

Gutierrez-Monreal, M. A. et al. Targeted Bmal1 restoration in muscle prolongs lifespan with systemic health effects in aging model. JCI Insight 9, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.174007 (2024).

Katewa, S. D. et al. Intramyocellular fatty-acid metabolism plays a critical role in mediating responses to dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 16, 97–103 (2012).

Rai, M. et al. Proteasome stress in skeletal muscle mounts a long-range protective response that delays retinal and brain aging. Cell Metab. 33, 1137–1154 e1139 (2021).

Robles-Murguia, M., Hunt, L. C., Finkelstein, D., Fan, Y. & Demontis, F. Tissue-specific alteration of gene expression and function by RU486 and the GeneSwitch system. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 5, 6 (2019).

Owusu-Ansah, E., Song, W. & Perrimon, N. Muscle mitohormesis promotes longevity via systemic repression of insulin signaling. Cell 155, 699–712 (2013).

Song, W. et al. Activin signaling mediates muscle-to-adipose communication in a mitochondria dysfunction-associated obesity model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8596–8601 (2017).

Ehlen, J. C. et al. Bmal1 function in skeletal muscle regulates sleep. Elife 6, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26557 (2017).

Harfmann, B. D. et al. Muscle-specific loss of Bmal1 leads to disrupted tissue glucose metabolism and systemic glucose homeostasis. Skelet. Muscle 6, 12 (2016).

Rai, M. & Demontis, F. Systemic Nutrient and Stress Signaling via Myokines and Myometabolites. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 85–107 (2016).

Rai, M. & Demontis, F. Muscle-to-Brain Signaling Via Myokines and Myometabolites. Brain Plast. 8, 43–63 (2022).

Rai, M., Hunt, L. C. & Demontis, F. Stress responses induced by perturbation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Trends Biochem. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2024.12.011 (2025).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. Imeta 1, e43 (2022).

Metsalu, T. & Vilo, J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W566–W570 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Work in the Demontis lab is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the NIH (R01AG075869). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Research at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is supported by the ALSAC. The scheme in Fig. 1a was generated with BioRender.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P. performed the JUMPptm analysis; C-L.C. made graphs in R; H.K.S. did the statistical analysis of JUMPptm data; F.D. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Poudel, S., Chuang, CL., Shrestha, H.K. et al. Pan-PTM profiling identifies post-translational modifications associated with exceptional longevity and preservation of skeletal muscle function in Drosophila. npj Aging 11, 23 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00215-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00215-2