Abstract

Achieving simultaneous high conductivity and mechanical durability in printed flexible electronics remains a central challenge. Here we report a systematic investigation of silver nanoparticle (AgNP) size effects on film performance using a pH-mediated synthesis that decouples particle size from organic content. This strategy enables direct assessment of size-dependent sintering and mechanical behaviors, previously obscured by varied polymer concentrations of traditional size control methods. With consistent organic content, AgNPs of smaller size demonstrated more effective sintering, forming denser and more cohesive microstructures, contrary to prior reports with varied organic concentration. This yielded highly conductive films with resistivities as low as 2.34 μΩ cm, approaching bulk silver. Additionally, electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing of these inks produced flexible circuits with significantly improved mechanical resilience. The resistance of a printed pattern remained stable over 1,000 bending cycles at a 2.9 mm radius and increased by only 56.7% after 50,000 cycles, with no visible microstructural cracking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing has emerged as a powerful tool for fabrication of electronic devices due to its low-cost, versatile manufacturing and rapid prototyping capabilities.1,2 This is especially advantageous for flexible electronics as it provides a method for depositing electronic materials onto flexible polymeric substrates that cannot withstand traditional high-temperature fabrication processes.3 Techniques such as inkjet,4 screen,5 aerosol jet,6 and electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing7,8 rely on functional inks composed of nanoparticle or precursor suspensions to produce conductive patterns.9 Such inks must maintain high colloidal stability to ensure long shelf lives along with proper rheological properties for smooth and precise printing. Once deposited, the material must also display the proper electrical properties, typically after some curing step. For flexible electronics, these inks must also maintain their electrical properties while conforming to various geometries, such as various body parts in the case of wearable devices. They must also be able to withstand many deformation cycles, such as bending, twisting, and stretching to ensure the reliability and longevity of the devices.10

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are widely used in functional inks due to their high conductivity, resistance to oxidation, and scalable methods.11 One property of the nano-ink that may drastically impact the electrical and mechanical properties of printed devices is the size of nanoparticles. However, previous studies have struggled to isolate the particle size effect. For example, different organic capping agents have been explored to control particle size12, and commercially purchased inks with different sizes but unknown compositions have been investigated.13 Additional studies have used synthesis approach by varying the ratio between silver precursor and organic capping agent to obtain different particle sizes.14,15,16,17 In general, it has been demonstrated that using a higher amount of capping agent, typically polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), with respect to silver leads to smaller nanoparticles. While the material compositions of these inks are the same regardless of particle size, the concentration of the components are not, as using a higher amount of organic content in the synthesis will result in a higher concentration of organic content in the ink.15 The additional amount of organic compound has a significant impact on the properties of the ink as the organic polymers are electronically insulating, and may also affect the mechanical performance of a printed film. Generally, inks with higher organic content display slower sintering and lower conductivity as more time and thermal energy are needed to break down higher amounts of the polymer. It has been reported that inks made with more capping agent, and therefore smaller particles, show lower conductivity than those made with less capping agent.14,15,16 However, the true effect of particle size on the properties of printed silver films may be obscured by the presence of varying amounts of polymeric stabilizers. In order to fully understand the effect of particle size on these properties, inks must be prepared with the same concentration of organic components.

In our previous study, we reported a bio-based silver nanoink using hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) as the capping agent.18 The HEC ink was found to be stable for more than 10 months and showed excellent rheology for producing high-resolution features using electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing. While the amount of HEC used is greatly reduced compared to PVP, the retention after washing is much higher. The amount retained on the silver nanoparticle surface remains sufficient to ensure colloidal stability. The printed patterns presented excellent low temperature sintering performance, yielding conductivity much higher than commercial alternatives. In addition, by simply tuning the pH of the synthesis, we discovered that the resulting nanoparticle size could be systematically altered. This provides a unique way to alter particle size without changing the organic compound in the system. Here, we leverage this unique control to isolate and investigate the role of particle size on sintering behavior, electrical conductivity, and mechanical performance, while eliminating the effects of the different organic content. Additionally, the thermal curing process by which these particles are sintered was investigated to determine optimal conditions to maximize electrical and mechanical performance. It is discovered that the smallest particle size showed the most effective particle sintering and in turn the best conductivity, approaching that of bulk silver under relatively low sintering temperature (150 °C). These particles also displayed excellent bending performance, exceeding many of the prior results reported in literature. We believe that without the excess polymer capping agent needed to make smaller particles, these particles display a higher level of sintering due to the high surface-to-volume ratio facilitating greater diffusion at particle contact points. This ultimately leads to more cohesive, durable, and electrically conductive films. The insights presented here offer a promising strategy for developing high-performance silver inks for flexible, next-generation devices.

Results

Synthesis of AgNPs

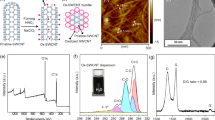

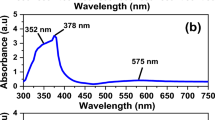

Four samples of silver nanoparticle ink were prepared by in-situ synthesis according to the previous work, with silver nitrate as the silver source, hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) as the stabilizer, L-ascorbic acid as the reducing agent, and ethylene glycol and water as the solvents.18 The major difference compared with conventional synthesis is the utilization of HEC as the stabilization agent instead of PVP. Our method allows us to systematically change the AgNP size by simply adjusting pH using different amounts of sodium hydroxide, while keeping all other conditions the same. At higher pH, the reactivity of L-ascorbic acid increases, leading to a higher rate of nucleation for silver and therefore a larger number of total nuclei.19,20 This ultimately leads to more but smaller nanoparticles upon complete reduction of the silver ions. The four samples used 12.0 mmol, 3.0 mmol, 0.12 mmol, and 0 mmol of sodium hydroxide. SEM images of the resulting AgNPs are shown in Fig. 1a-d, respectively. It is observed that the synthesis with the highest amount of sodium hydroxide resulted in the smallest and most monodisperse nanoparticles of ~50 nm in diameter. Meanwhile, the sample synthesized without any sodium hydroxide resulted in much larger and far more polydisperse nanoparticles, the largest of which being upwards of 500 nm in diameter. In total, a trend of decreasing size with increasing NaOH content (increasing pH) is observed to be consistent across all four samples. When attempting to use a higher amount of NaOH than 12.0 mmol, the synthesis became inconsistent, resulting in heavy flocculation of the silver particles. For the remainder of this paper, the samples will be referred to as “Small” (S), “Medium” (M), “Large” (L), and “X-Large” (XL) in order of increasing size. Figure 1e-h display the nanoparticle size distribution for each of the samples from smallest to largest. The samples were found to have average particle sizes of (S) 47.4 ± 13.7 nm, (M) 80.2 ± 27.3 nm, (L) 129.0 ± 45.2 nm, and (XL) 196.6 ± 99.7 nm. Relative to particle size, the standard deviations are (S) ± 29%, (M) ± 34%, (L) ± 35%, and (XL) ± 51%. The larger particles therefore exhibit broader size distributions. The samples were further analyzed under UV-Vis spectroscopy, shown in Fig. 1i. It is observed that the smallest nanoparticles display the narrowest peak at the lowest wavelength. For each sample, as particle size increases, the peak becomes broader and sits at a higher wavelength. This further indicates the monodispersity and uniformity of samples of smaller nanoparticles compared to the larger ones, consistent with SEM observation.

SEM images of samples prepared with a 12.0 mmol of NaOH (Sample S), b 3.0 mmol of NaOH (Sample M), c 0.12 mmol of NaOH (Sample L), and d) 0 mmol of NaOH (Sample XL). Particle size distributions for e sample S, f sample M, g sample L, and h sample XL. i UV-Vis data and a sample color for each ink. j Thermogravimetric analysis for the inks. k Rheology data for the inks.

Each nanoparticle sample was washed twice with ethanol and acetone to remove excess byproducts and then dispersed in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 50 wt% to form the final ink formulations. The washing steps ensured that only AgNPs capped with the organic stabilizer remained. To determine if pH-mediated size control affected residual organic content, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on dried out samples of each of the four inks. As shown in Fig. 1j, all four samples displayed similar organic content, with mass losses ranging between 4.8–5.3% upon heating above the polymer’s degradation temperature. This translates to a retention of 48–53% of the original of stabilizer used during the synthesis. Importantly, no correlation was observed between nanoparticle size and the amount of residual organic content. Thus, it can be concluded that using this method to control the nanoparticle size has no effect on the organic content of the inks.

Ink rheology

The rheological behavior of nanoparticle inks plays a critical role in determining their printability. The four inks of different particle size were tested for their rheological properties over a wide shear rate range (0.1–1000 s−1) as shown in Fig. 1k. At low shear rates ( < 10 s−1), a clear trend of increasing viscosity is observed with decreasing particle size, ranging from ~600 mPa s for the largest particles (XL) to ~1400 mPa s for the smallest particles (S) at the lowest shear rate. This increased viscosity can be attributed to the higher surface area at the same mass and increased particle-particle interactions in smaller particles.21 The smallest particles also show a steep shear-thinning profile, while the largest particles exhibit nearly Newtonian behavior, with minimal viscosity change in the same shear range. M and L samples also follow the trend. As shear rate increases beyond 10 s−1, all four samples converge to a very similar rheology profile, and by 1000 s−1, the viscosity values differ by less than 80 mPa s. For this reason, the ink solids content rather than viscosity was matched in this study. The shear-thinning behaviors are consistent with the breakdown of interparticle interactions under high shear, where hydrodynamic forces dominate, leading to similar profiles for similarly composed solutions.22 Viscosity is a critical factor for printing applications and varies by printing technique. Piezo-based inkjet printing requires very low viscosity inks (<10 mPa s),23 while screen printing utilizes much more viscous pastes (>1000 mPa s). Other techniques, such as EHD printing, are more versatile and can accommodate a broad viscosity range (1–1000 mPa s).24 We have also demonstrated that higher viscosity inks can yield finer printed features under EHD printing.18 The ability to tune ink rheology via particle size, without altering ink composition, provides a versatile platform for adapting to a variety of printing technologies.

Electrical performance

Another key property influenced by AgNPs morphology is the electrical performance. Previous reports have shown that increasing amount of polymer in the synthesis can hinder sintering and significantly lower conductivity of the films.18 Now with the organic content consistent in our study, the effect of particle size on the sintering behavior can be isolated and systematically evaluated. Inks containing S, M, L, and XL particles were deposited onto glass slides and sintered for 30 minutes at temperatures ranging between 150–250 °C in 25 °C increments. The resistivities of the films were measured and displayed in Fig. 2a, along with their corresponding conductivities (1/resistivity) normalized to the conductivity of pure silver. A clear size-dependent trend is observed at every sintering temperature. Smaller particles consistently showed lower resistivity than the next size above them. At 150 °C sintering, the smallest sample exhibits a resistivity of 6.34 μΩ cm, equating to a conductivity 25.1% of bulk silver. By contrast, the XL sample has a resistivity of 75.72 μΩ cm when sintered at 150 °C, equating to just 0.46% the conductivity of bulk silver. Samples M and L follow the trend with resistivities of 14.76 and 31.09 μΩ cm (conductivities of 10.9% and 5.3% bulk silver), respectively. As expected, resistivity decreases with increasing sintering temperature due to enhanced polymer decomposition and improved diffusion of the surface atoms at elevated thermal energy. At 250 °C, the S sample achieves a resistivity of just 2.34 μΩ cm, corresponding to 68.2% the conductivity of bulk silver. The M, L, and XL samples also approach bulk values, with resistivities of 2.48, 2.79, and 2.94 μΩ cm (64.4%, 58.3%, and 54.4% conductivities), respectively. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on results to assess the main effects of particle size and sintering temperature. All cases reported P < 0.0001, confirming the statistical significance of the observed trends.

a Electrical resistivity and conductivity (as a percentage of pure silver) measurements for each ink after sintering at temperatures ranging from 150–250 °C for 30 minutes. b SEM images of each ink after sintering at each temperature. c A comparison of resistivities achieved by this work to those of other silver nanoparticle inks in literature.

To understand the fundamental mechanism for the observed conductivity trend, the microstructures of the sintered films were systematically analyzed. SEM images of film surfaces for each particle size and sintering temperature combination are presented in Fig. 2b, and additional SEM images of the film cross-sections are presented in Fig. S1. A clear correlation is observed between particle size and sintering behavior, and the cross-sectional view is consistent with the top-down view. The sintering activity is greater for smaller particles at each temperature, and initiates at lower temperatures. In fact, the temperature at which significant particle fusion is first observed for each sample is shown to increase with particle size. Visible necking of the particles, an indication of sintering initiation, is first observed at 150 °C for sample S, 175 °C for sample M, 200 °C for sample L, and 225 °C for sample XL. These are marked in the figure with a thick red outline. Notably, these temperatures also correspond to the point at which each sample displays a conductivity greater than 20% that of bulk silver, further confirming that high conductivity is induced by coalescing between particles. By 250 °C, all four samples show similar microstructures, characterized by a continuous film made up of large grains, which accounts for their converging low resistivity values.

The synthesis method presented in this work decouples particle size control from capping agent concentration, allowing inks to retain the advantages of smaller particles while also enabling the amount of organic capping agent to be minimized to only what is necessary for colloidal stability. To demonstrate this advantage, the resistivity of the small-particle ink developed in this study is benchmarked against high-conductivity silver nano-inks reported in the literature, as well as bulk silver, as shown in Fig. 2c.13,25,26,27,28,29,30 All referenced samples were thermal sintered, with the temperatures indicated and times ranging from 20 and 60 minutes, comparable with our study. While alternate sintering techniques, such as laser and photonic sintering, allow for the ability to sinter AgNPs at lower ambient temperatures, they generate highly localized heat at the point of sintering that can be difficult to quantify.31 The ink of the smallest particle size presented in this work exhibits superior electrical conductivity, with the mark of 2.34 μΩ cm at 250 °C being the lowest reported at any sintering temperature among the referenced literature. In addition, exceptional performance of the ink is still reported at each of the lower sintering temperatures down to 150 °C, with just 4x the resistivity of bulk silver. In fact, there are diminishing returns when sintering above 200 °C, at which the mark of 2.95 μΩ cm is less than 2x that of bulk silver. This is notable for the printing of flexible devices. While rigid substrates and some flexible polymers, such as polyimide and PDMS, can handle higher sintering temperatures ( > 200 °C), others, such as PET, PEN, and TPU, are less thermally stable, and lower processing temperatures are required. To verify the use of these inks in flexible devices, additional conductivity experiments were performed on inks deposited and sintered on polyimide for 30 minutes, with the results displayed in Fig. S2. The trend with particle size was consistent with that observed for samples printed on glass. High conductivity values were still achieved, though slightly lower than on glass. This is likely due to the more limited heat flow to the film during sintering, as polyimide displays lower thermal conductivity ( ~ 0.2 W m-1 K-1) than glass ( ~ 1.0 W m-1 K-1). Nonetheless, the values of 16.60, 3.74, and 2.50 μΩ cm for the smallest particle size ink at 150, 200, and 250 °C sintering still indicate exceptional sintering and electrical performance.

Mechanical performance

In addition to electrical performance, the mechanical properties of the inks were also evaluated to assess their use in flexible electronics. Such devices must be able to move freely and conform to various geometries, which requires printed materials that are both mechanically robust and capable of maintaining electrical integrity under repeated deformation. To this end, the characterization was carried out on a custom-built device through cyclic bending, where the electrical properties were monitored both at various bending radii and through several cycles and normalized against their initial values.

Bend testing samples were prepared though EHD printing on flexible, polyimide substrates. Figure 3a displays an example of the prepared samples, which includes a central line of silver ink printed at 2.0 cm long, ~200 μm wide, and <1 μm thick. Printing conditions were optimized to keep the samples with different inks to similar dimensions. Contact pads were prepared from additional silver ink painted on, and the samples were sintered at various temperatures to induce conductivity. Copper wires were then attached to the contact pads using silver epoxy. Due to the geometries of these components, the resistance through the sample is dominated by the lowest cross-sectional area. This is the region where the deformation by bending will occur. Figure 3b shows a diagram of the sample bending setup. The flexible substrate is secured to a fixed stage at one end and a moving stage at the other, which induces curvature in the sample as it moves toward the fixed stage. The bending radius is determined through image analysis by fitting of a circle to the curvature, and the resistance is monitored through electrical equipment attached to the copper wires. Additional details of the sample and bending setup can be found in the methods section.

a A bend testing sample printed on a flexible polyimide substrate. b Schematic of the bend testing system. Measurements of change in relative resistance as a function of bend radius for samples sintered at c 150 °C, d 200 °C, e 250 °C for 30 minutes. Measurements of change in relative resistance over 1000 bending cycles (radius 2.9 mm) for samples sintered at f 150 °C, g 200 °C, h 250 °C for 30 minutes.

Samples of each of the four inks were sintered at temperatures of 150 °C, 200 °C, and 250 °C for 30 minutes. The samples were then bent at different radii starting from flat and progressing toward a minimum radii of 2.9 mm. Smaller values lead to higher tension on the bent sample, and are therefore more demanding on the integrity of the printed pattern. During bending, the samples were evaluated by their change in resistance as a percentage of the original resistance (ΔR/R0). The results of the change in relative resistance while bending are displayed in Fig. 3c-e, separated by sintering temperature. For each test-case, at least 3 samples replicates were prepared and measured. The results were averaged with standard deviations shown as error bars. Across all samples, it is shown that as the bend radius decreases, the change in relative resistance increases, thus the samples show higher resistance under deformation. This is likely due to the separation of contact points between silver grains under tension impeding current flow. It is also observed across each temperature that samples made from inks with smaller particle sizes show lower change in relative resistance compared to samples of larger particle inks. After sintering at 150 °C, samples of inks S, M, L, and XL show average resistance increases of 1.71%, 2.59%, 3.85%, and 5.39% respectively when bent to a 2.9 mm radius, shown in Fig. 3c. Likewise, the samples show average resistance increases of 1.47%, 2.46%, 3.17%, and 4.57% after 200 °C sintering (Fig. 3d) as well as 1.10%, 2.07%, 3.28%, and 5.00% after 250 °C sintering (Fig. 3e) in order of increasing particle size when bent to the minimum radius.

All samples were then bent to a radius of 2.9 mm 1000 times, and resistance changes were measured at every 100 cycles with the sample in the flat position (Fig. 3f-h). The trends observed here follow very closely to what was observed when measuring relative resistance against bending radius. For the samples sintered at 150 °C, shown in Fig. 3f, average relative resistance increases of 2.16%, 6.09%, 11.54%, and 21.37% were observed after 1000 cycles for samples S, M, L, and XL, respectively. This once again displays the trend of increasing changes in resistance with increasing particle size. When sintered at 200 °C, the samples displayed average relative resistance increases of 10.5%, 20.5%, 39.3%, and 66.0% in order of increasing particle size. Notably, the samples of all particle sizes displayed higher jumps in resistance than their 150 °C sintered counterparts. Finally, when sintered at 250 °C, the samples displayed average relative resistance increases of 15.5%, 38.3%, 74.5%, and 113.9% in order of increasing particle size, once again displaying higher increases in resistance compared to samples sintered at the lower temperatures.

To better compare samples across all temperatures, the average relative resistance change of each sample after 1000 bending cycles is summarized in Fig. 4a. As previously discussed, samples of smaller particle size show improved robustness compared to samples of larger particle size at each sintering temperature, while increasing sintering temperature results in decreased robustness for samples of every particle size. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effects of particle size, sintering temperature, and their interaction. The main effects of both particle size and temperature were highly significant (P < 0.0001), and their interaction was also significant (P = 0.034). These results indicate that the observed trends are statistically significant at the 0.05 level, with independent contributions from particle size and temperature. To understand the mechanism behind these trends, the microstructures of each sample at the point of bending are analyzed under SEM, shown in Fig. 4b. Two factors were identified as key contributors: defect morphology and packing density. At 150 °C, no noticeable defects are observed in any sample. At 200 °C, defects are observed in all samples. In the case of samples S and M, transverse cracks are observed within densely packed silver grains. In contrast, samples L and XL exhibit less well-defined defects, manifesting as small, scattered gaps that are not directionally aligned. At 250 °C, similar defects are observed as 200 °C, just more pronounced. This noticeable increase in cracking helps to explain the increase in relative resistance changes for each sample as sintering temperature increased, as cracking disconnects pathways for electron flow.

a Summary of relative resistance change for all samples after bending to 1000 cycles. b SEM images of the microstructure at the bending point for each sample after 1000 bending cycles. c Comparison of the relative resistance change for all samples after bending to 1000 cycles to the voiding percentage of the microstructure. d SEM images showing the amount of voiding in the microstructure for each sample.

To understand why samples of smaller particle size showed superior robustness to those of larger sizes, it is important to look at not just the defects, but also the underlying microstructure of pores and sintering action in relationship to particle size. It is noticeable across each temperature that samples with smaller particles show a more densely packed arrangement of silver grains, while samples with larger particles show a more porous microstructure. Quantitative porosity analysis was performed (Fig. 4c) on SEM images taken from undeformed regions to exclude the influence of bending-induced defects (Fig. 4d). The results confirm that the porosity (marked in red) increases with particle size. The higher porosity for films of larger particles can be attributed to the reduced packing efficiency and larger interstitial voids between particles of greater diameters. The lower viscosity of the inks with larger particles may also be contributing to the higher porosity, as those films will spread more upon initial deposition. Additionally, for each particle size, porosity is smaller and more frequent at lower sintering temperatures and becomes larger but less frequent at higher temperatures. This coalescence of pores is consistent with grain coalescence during sintering. On the other hand, the porosity also indicates how well interconnected particles are. The porosities of all samples are plotted against their change in relative resistance at 1000 cycles, separated by sintering temperature, as shown in Fig. 4c. It is clearly seen that increasing porosity (associated with increasing particle size) coincides directly with increasing change in relative resistance at each temperature. In fact, strong linear fits (R2 > 0.97) are observed in correlation with the plots of porosity vs change in relative resistance at each temperature, with increasing slopes for increasing temperatures.

In our study, hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) serves as the capping agent, which begins to degrade rapidly around a temperature of 250 °C. This is evidenced by the TGA results of HEC powder show in Figure S3 as well as the inks previously displayed in Fig. 1f. We hypothesize that high sintering temperature may completely remove HEC and lead to worse mechanical performance. To validate this, the adhesive strength of the sintered films on the polyimide substrate was evaluated following ASTM F1842 peel test after sintering at 150 °C, 200 °C, and 250 °C for 30 minutes. The results (Fig. 5a) show strong adhesion to the substrate for films sintered at 150 °C and 200 °C. No portion of the films were removed during the peel test, so both films receive the top grade of 5 per the ASTM standard. By contrast, when sintered at 250 °C, the peel test displays extensive detachment of the film, resulting in a grade of 1 per the standard (35%-65% removed). This indicates much worse adhesion, likely caused by the degradation of the HEC. Given that particle–substrate adhesion reflects the presence of interparticle binding as well, this loss of adhesion provides a mechanistic explanation for the diminished bending performance of films sintered at 250 °C. To further quantify HEC degradation, TGA was performed on samples of silver ink samples after sintering at the same three temperatures for 30 minutes. The results were compared against that of the unsintered ink, shown in Fig. 5b. It is observed that when sintering at 150 °C, there is effectively no change in the organic content, matching that of the unsintered ink at 5.2%. By contrast, significant degradation of the HEC is observed when sintered at 250 °C, with just 0.9% organic content in the film. Additionally, the ink sintered at 200 °C shows just 1.7% organic content, indicating that degradation of the polymer can occur when held at this temperature as well.

a Peel-adhesion testing of silver ink films on polyimide after sintering at 150 °C, 200 °C, and 250 °C. b Thermogravimetric analysis of silver inks after sintering at 150 °C, 200 °C, and 250 °C. c Comparison between different sintering time/temperature combinations for each ink. d Change in relative resistance as a function of bend radius for ink L sintered at 150 °C for different times. e Change in relative resistance after 1000 cycles (radius 2.9 mm) for ink L sintered at 150 °C for different times. f Change in relative resistance after 50,000 cycles (radius 2.9 mm) for inks L and S sintered at 150 °C for 24 hours, and SEM image of the microstructure of sample S at the bending point.

These findings offer insight of a fundamental trade-off in sintering conditions and help explain why no cracking was observed in any of the bending samples sintered at 150 °C. The high polymer content in the printed inks provided much stronger binding of the particles compared to the lower amounts in the prints sintered at 200 °C and 250 °C. To obtain optimal electromechanical behavior, a high degree of sintering is desired for high electrical conductivity and better particle-particle interconnects. On the other hand, a low sintering temperature is desired to minimize the degradation of the polymer capping agent which behaves as a binder for the particles. To address the contradiction, we propose extending the sintering duration at low temperature as a strategy to achieve both strong electrical and mechanical performance. Figure 5c compares the resistivities of films sintered at 150 °C for both 30 minutes and 24 hours, along with those sintered at 200 °C for 30 minutes. For all particle sizes, prolonged sintering at 150 °C (24 hours) greatly improves the film’s conductivity compared to 30 minutes, and yields comparable resistivity to those obtained by sintering at 200 °C. This indicates improved particle–particle necking and densification without degrading the polymer. By staying well below the degradation temperature of the capping agent, the polymer is fully retained to further improve mechanical properties.

To evaluate the benefits of this approach, additional bending tests were performed in ink L sintered at 150 °C for 30 minutes, 3 hours, and 24 hours. SEM images of the microstructures of these films are displayed in Fig. S4. Although no major morphological differences were observed, increased particle merging became evident with longer sintering times, consistent with the improved performance at extended durations. As shown in Fig. 5d, the average resistance increase under a bending radius of 2.9 mm was reduced from 3.85% (30 min) to 2.67% (3 h), and further to 0.91% (24 h). Cyclic bending results over 1000 cycles at the same radius (Fig. 5e) show similar trends: resistance increased by 11.54% with 30 minutes sintering, 4.37% with 3 hours, and just 1.77% with 24 hours, the lowest observed across all samples thus far. These results confirm that extended low-temperature sintering simultaneously enhances electrical conductivity and mechanical durability. To evaluate the long-term fatigue performance, this sample was bent to a radius of 2.9 mm for 50,000 total cycles (Fig. 5f). After 50,000 cycles, the sample displayed a relative resistance increase of 77.0%. While there is no standard methodology for performing this test, typical cyclic bending radii reported in literature commonly range between 2 and 10 mm, with smaller radii being more demanding.32,33,34 As such, it becomes difficult to make direct comparisons. However, in other works where silver nano-inks were tested for long-term fatigue at a similar bending radius ( ~ 4 mm), all samples showed relative resistance increases between 100%-1000% after 30,000+ bending cycles.16,35 With this in mind, the 77.0% increase observed in our testing after 50,000 cycles at an even tighter bending radius indicates remarkable durability.

Finally, to verify the role of particle size, a long-term bending test was performed on Ink S, also sintered at 150 °C for 24 hours and bent to a 2.9 mm radius for 50,000 cycles. The film showed just a 56.7% increase in relative resistance, the best performance recorded, indicating exceptional mechanical reliability and the superiority of smaller particles. When inspected under SEM imaging, no noticeable defects were observed at the point of bending, further displaying the advantage of the extended, low-temperature sintering process.

Discussions

Our method of synthesizing Ag nanoparticles contrasts sharply with conventional approaches, in which nanoparticle size is controlled by varying the amount of organic capping agent. Increasing the concentration of capping agent generally leads to smaller nanoparticles, but also results in higher residual organic content in the final ink.14,15,16,17 Since the organic content strongly influences key ink properties, including electrical conductivity and mechanical integrity, it introduces a confounding variable. By contrast, the pH-mediated size control method employed in this study decouples particle size from stabilizer concentration, enabling direct investigation of size-dependent effects without the interference of varying organic content. By holding the polymer content constant, it was demonstrated that smaller nanoparticles, synthesized at higher pH, consistently yield superior performance. Specifically, inks with the smallest particles achieved a resistivity of just 2.34 μΩ cm, equating to 68.2% the conductivity of pure silver. The smallest particles were also found to maintain the conductivity best after repeated bending.

Previous studies have shown broader size distributions can also improve sintering, as larger particles provide longer conduction pathways while smaller particles help fill voids to create denser films.36 However, in our work the smaller and more monodisperse particles still showed much better sintering. These results highlight the critical role of nanoparticle size instead of particle size distribution in determining the sintering efficiency and resulting electrical performance of printed films. By using our unconventional synthesis to decouple particle size from organic content, the underlying trend becomes clearly observable, smaller particles consistently lead to improved conductivity due to more efficient sintering, a relationship that was previously obscured by variations in organic dispersant content.

The enhanced sintering kinetics of smaller particles can be partially explained by Fick’s laws of diffusion. According to Fick’s first law, diffusion flux is directly proportional to the concentration gradient, which becomes more pronounced as the surface area increases.37 Smaller particles have higher specific surface area, and therefore more sites for atomic diffusion as well as steeper concentration gradients at particle interfaces. This promotes higher atomic fluxes and accelerated mass transport, which are critical for neck growth and densification during sintering. Additionally, the higher surface-to-volume ratio of smaller particles results in higher free energy.38 This increased surface energy acts as the key driving force for diffusion and particle sintering. As a result, atomic mobility is enhanced, leading to faster densification and coarsening at lower temperatures.39 Although this behavior of the increased sintering activity with decreased particle size has not been extensively shown for polymer-coated silver inks, it is well-documented in the field of powder metallurgy and ceramic processing.40,41 In these fields, Herring’s scaling law predicts that the time required to achieve a given degree of sintering is inversely proportional to the cube of particle size.42 While the presence of polymer coatings in nanoparticle inks introduces additional complexity not captured by these classical models, the consistent organic content across all samples in this study allows the fundamental principles of diffusion-driven sintering to remain applicable and clearly reveal the role of particle size in sintering efficiency and film conductivity.

In summary, smaller AgNPs demonstrate significantly enhanced sintering activity, which in turn translates to better electrical conductivity in the resulting printed films. However, previous studies that have used different amounts of PVP in the synthesis to adjust nanoparticle size have reported opposite of these results. In each of these studies, larger particles led to faster sintering and more conductive films.14,15,16 This discrepancy can be attributed to the higher organic content associated with smaller nanoparticles in those systems. The excess capping agent not only impedes particle-particle contact, but also requires more energy to degrade the polymer, thereby slowing the sintering process and diminishing the electrical performance. These findings showcase a major limitation in the conventional approach of controlling particle size through capping agent concentration. The benefits of the inherently favorable sintering kinetics of smaller particles are masked by the accompanying increase in organic content. As a result, the full potential of smaller particles to produce highly conductive films remains unrealized. The ability to achieve high conductivity at low sintering temperatures broadens the applicability of the ink, particularly for fabricating flexible electronic devices on polymeric substrates and other temperature-sensitive components.

Based on our findings, we further propose a porosity and defect-driven mechanism to explain the bending performance. Samples with larger particles exhibit higher porosity, resulting in fewer contact points between particles. Additionally, larger particles also undergo significantly weaker sintering, leading to weaker inter-particle connections. As a result, mechanical stress during bending is localized at these weaker and less frequent particle-particle connections, which are more susceptible to separation and failure, leading to higher increases in resistance. Cracks in the film, however, are not observed as the weakly sintered particles do not take the form of a dense grain structure, thus separations at particle interconnects are visibly indistinguishable from the as-deposited particles. Conversely, in more compact films of smaller particles, particles are more densely packed with more frequent interparticle connections, effectively distributing and reducing the localized stress. Additionally, these connections are stronger due to the improved sintering action of smaller particles, so the film is more mechanically robust. This behavior of more compact films leading to improved bending performance aligns with the previous findings of Liu et al.43 At the increased sintering temperature of 200 °C, the formation of long cracks in the dense sintered grain structures dominates and lead to worsened performance. Finally, at 250 °C sintering, increased defects further lead to worse performance for all samples. In summary, our analysis reveals that both defects and microstructural packing density are two critical factors governing the bending performance.

Additionally, to understand why increased sintering temperature leads to increased cracking and therefore decreased mechanical robustness, it is necessary to consider not only the sintered microstructure but also the role of the organic capping agent. While it is necessary to sinter away polymers covered on the particle surface to yield a conductive film, retaining a small amount of polymer after sintering may benefit mechanical performance. Residual polymer may act as a binder or adhesive to reinforce interactions between the particles or the particles and the substrate. This reinforcement can hold the film together and mitigate crack formation during bending.44 A previous study by Kim et al. showed that bending performance was significantly worsened when sintering above the degradation temperature of the capping agent.45 This provides an additional mechanism for improving the mechanical performance.

The study revealed the complex interplay between sintering temperature and film performance. While increased temperature enhances grain coalescence and conductivity, it also degrades the organic capping agent, which contributes to film adhesion and mechanical robustness. To balance these opposing factors, an extended low-temperature sintering strategy was employed. This approach preserved the polymer binder while enabling sufficient sintering, resulting in significantly improved electromechanical performance. Under optimized conditions, the best-performing ink composed of smallest particles was able to bend at a radius of 2.9 mm for 50,000 cycles while only accruing a 56.7% increase in total resistance. These findings highlight the critical role of particle size in determining both electrical conductivity and mechanical durability. The results not only reveal fundamental insights into the sintering behavior of nanoparticle inks but also demonstrate that precise control over particle size and processing conditions is key to unlock the full potential of nanoparticle-based printable electronics.

Methods

Materials

2-hydroxyethyl cellulose (90 000 g mol−1), and L-ascorbic acid ( > 99% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Silver nitrate, sodium hydroxide, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, >99.7% purity), and ethylene glycol were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Silver Epoxy 8331D was purchased from MG Chemicals. Stranded copper hookup wire was purchased from SparkFun Electronics.

Ink preparation

The inks were prepared according to the previous study.18 A stock solution of 7.5 M aqueous sodium hydroxide was prepared. For each sample, 3.00 g of silver nitrate was dissolved in 2 mL of DI water, and 1.50 g of L-ascorbic acid was dissolved in 7.5 mL of DI water (a 2:1 ratio of AgNO3 to L-ascorbic acid). 0.20 g of HEC powder was dissolved in 15 mL of ethylene glycol under 500 rpm stirring at 100 °C. Once the HEC was fully dissolved, different amounts of the sodium hydroxide stock solution were added for the different samples: 0 mL, 0.016 mL, 0.40 mL, and 1.60 mL. This was immediately followed by the addition of the silver nitrate solution and then the L-ascorbic acid solution, resulting in a total reaction volume of 24.5–26.1 mL depending on the sample. The mixture was left to stir for 30 seconds to allow complete reduction of the Ag+ ions to AgNPs. The resulting silver nanoparticle solution was washed with ethanol and acetone twice, and the particles were separated out through centrifugation. The supernatant from the centrifugation was tested for remaining Ag+ ions with NaCl solution, and the lack of precipitants indicated 100% yield of the reaction. The particles were then suspended in 1.5 mL of DMSO resulting in silver ink with 50 ± 1 wt% loading.

EHD inkjet printer and printing procedure

The details of the EHD inkjet printer setup and printing procedure followed protocols reported in previous publications.18,46,47 The home-built EHD printer consists of a translating stage, positive and ground electrodes, glass micro-nozzle and syringe, signal generator, and voltage amplifier. The ink was loaded in the micro-nozzle and attached to the syringe, then mounted to Z stage as an entity. The positive electrode was connected to the micro-nozzle and contacted the ink directly by using a metal conductor, and ground was mounted under a glass substrate. The voltage signal was generated by the signal generator, amplified 1000 times by the amplifier, and then applied to the ink through the metal electrode. Before printing, the ink was loaded to the syringe and the micro-nozzle was rinsed with acetone to avoid clogging. Substrates were precleaned with ethanol. The XY stages were levelled off to maintain a constant stand-off distance during the printing. A pulse signal was used to achieve better control of droplet size and the jetting frequency for a precise control of the printing resolution. The pattern was programmed and would be finished automatically.

Thermal characterization

Small deposits of ink (0.05–0.10 g) were dried out in an oven set to 70 °C. Thermogravimetric analysis was performed on the remaining solids using a Thermal Advantage TGA 5500. The samples were analyzed over a temperature range of 25 °C to 800 °C at a ramp of 20 °C per minute.

Rheology characterization

Rheology measurements were taken using an Anton Paar MCR 92 rheometer with a 25 mm 1° cone-and-plate setup with a gap dimension of 0.01 mm. For the measurement, the shear rate was increased from 0.1 to 1000 s-1 over 5 minutes with a logarithmic selection.

SEM imaging and processing

An FEI Quanta 250 FE Scanning Electron Microscope was used to image the AgNPs. ImageJ was used to measure particle sizes. ImageJ was also used to determine the percentage of voiding in the films by measuring the area that fell under an image-specific brightness threshold.

Conductivity measurement

The inks were spin coated into thin films on plasma-treated 25 × 25 mm cover glass slides and left to air-dry overnight. The films were then sintered on hot plates at the specified temperatures for 30 minutes each. Sheet resistance measurements were taken using a Jandel RM2 4-point probe. The films were then cross-sectioned, and the cross-sectional thickness was measured using SEM and ImageJ. For each particle size and sintering temperature combination, three independent samples were prepared. For each sample, resistivity was measured at five different locations, and cross-sectional thickness was measured at three locations, with each thickness measurement repeated three times using high resolution laser confocal microscope. Typical film thickness was approximately 1 μm. Resistivities were calculated by the following equation, where ρ is resistivity, V is voltage, I is current, and t is thickness:48

Bend testing sample preparation

Polyimide substrates were prepared with dimensions of 7.0 cm by 2.5 cm and then plasma-treated. The silver nano-inks were printed onto the substrates using the EHD printer. The sample patterns, shown in Fig. 3a, consist of a central line of printed ink 2.0 cm long and ~200 μm wide. On either side of the line, contact pads were prepared by painting on additional silver ink. The samples were sintered on hot plates at the specified temperatures for 30 minutes each. Once sintered, two stranded copper wires were attached to each contact pad using silver epoxy. The samples were then placed in an oven at 70 °C for 20 minutes to cure the epoxy.

Bend testing system

A Creality Ender-3 V2 3D printer was modified to create a bend testing system shown in Figure S5. Custom clamps designed to secure the bend testing samples were 3D printed from polylactic acid. The 3D printer nozzle head was removed from the chassis and replaced with one clamp. The other clamp was secured statically to the system such that the two clamps would move closer together by controlling the x-position of the chassis. A sample was inserted, and the bend radii at different x-positions of the chassis were measured by fitting a circle to the bending curvature at each position as displayed in Fig. S6. The x-position was controlled manually for all resistance measurements at different bending radii. For cyclic bending, the print function of the 3D printer was utilized by preparing custom g-code to automatically control the x-position of the chassis for the desired number of cycles. The chassis moved at 1500 mm/min, with a bending rate of 30 cycles per minute at a bending radius of 2.9 mm. Three replicates were performed for each ink and condition. To measure the resistance across the samples, the copper wires connected to the sample were connected to a Keithly 6220 precision current source and a Keithley 6514 system electrometer (each with one connection on either side of the sample). The current source was used to supply a steady current (I) across the sample, while the electrometer read the voltage (V) across the sample. Resistance (R) was determined by V = IR. All bending experiments were performed in ambient, room-temperature conditions.

Data availability

All raw data are deposited into a public repository doi:10.7910/DVN/ZOVNA2.

References

Wiklund, J. et al. A Review on Printed Electronics: Fabrication Methods, Inks, Substrates, Applications and Environmental Impacts. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 5, 89 (2021).

Zikulnig, J. et al. Printed Electronics Technologies for Additive Manufacturing of Hybrid Electronic Sensor Systems. Adv. Sens. Res. 2, 2200073 (2023).

Espera, A. H., Dizon, J. R. C., Valino, A. D. & Advincula, R. C. Advancing flexible electronics and additive manufacturing. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 61, SE0803 (2022).

Beedasy, V. & Smith, P. J. Printed Electronics as Prepared by Inkjet Printing. Materials 13, 704 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ink formulation, scalable applications and challenging perspectives of screen printing for emerging printed microelectronics. J. Energy Chem. 63, 498–513 (2021).

Wilkinson, N. J., Smith, M. A. A., Kay, R. W. & Harris, R. A. A review of aerosol jet printing—a non-traditional hybrid process for micro-manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 105, 4599–4619 (2019).

Yin, Z. et al. Electrohydrodynamic printing for high resolution patterning of flexible electronics toward industrial applications. InfoMat 6 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Memory Manufacture Under Microgravity (MMuM): In-Space Manufactured ZnO-Based Resistive Random Access Memory for Emerging Computing Application. Adv. Electron. Mater. 11, 2500114 (2025).

Sanchez-Duenas, L. et al. A Review on Sustainable Inks for Printed Electronics: Materials for Conductive, Dielectric and Piezoelectric Sustainable Inks. Materials 16, 3940 (2023).

Htwe, Y. & Mariatti, M. Printed graphene and hybrid conductive inks for flexible, stretchable, and wearable electronics: Progress, opportunities, and challenges. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 7, 100435 (2022).

Tan, H. W., An, J., Chua, C. K. & Tran, T. Metallic Nanoparticle Inks for 3D Printing of Electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1800831 (2019).

Seo, M., Kim, J. S., Lee, J. G., Kim, S. B. & Koo, S. M. The effect of silver particle size and organic stabilizers on the conductivity of silver particulate films in thermal sintering processes. Thin Solid Films 616, 366–374 (2016).

Park, H.-J. et al. Physical Characteristics of Sintered Silver Nanoparticle Inks with Different Sizes during Furnace Sintering. Materials 17, 978 (2024).

Ding, J. et al. Preparing of Highly Conductive Patterns on Flexible Substrates by Screen Printing of Silver Nanoparticles with Different Size Distribution. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11 (2016).

Mo, L. et al. Nano-Silver Ink of High Conductivity and Low Sintering Temperature for Paper Electronics. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 14 (2019).

Shang, Y. et al. Improvement of Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Printed Silver Wire by Adjusting Particle Size Distribution of Multiscale Silver Nanoparticle Ink. J. Electron. Mater. 51, 6503–6511 (2022).

Zhao, C. F., Wang, J., Zhang, Z. Q., Sun, Z. & Maimaitimin, Z. Silver-Based Conductive Ink on Paper Electrodes Based on Micro-Pen Writing for Electroanalytical Applications. ChemElectroChem 9 (2022).

Kirscht, T. et al. Silver Nano-Inks Synthesized with Biobased Polymers for High-Resolution Electrohydrodynamic Printing Toward In-Space Manufacturing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 44225–44235 (2024).

Qin, Y. et al. Size control over spherical silver nanoparticles by ascorbic acid reduction. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 372, 172–176 (2010).

Goia, D. V. Preparation and formation mechanisms of uniform metallic particles in homogeneous solutions. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 451–458 (2004).

Wang, T., Wang, X., Lou, Z., Ni, M. & Cen, K. Mechanisms of Viscosity Increase for Nanocolloidal Dispersions. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 11, 3141–3150 (2011).

Koca, H. D. et al. Effect of particle size on the viscosity of nanofluids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 1664–1674 (2018).

Cao, T., Yang, Z., Zhang, H. & Wang, Y. Inkjet printing quality improvement research progress: A review. Heliyon 10, e30163 (2024).

Guo, L., Duan, Y., Huang, Y. & Yin, Z. Experimental Study of the Influence of Ink Properties and Process Parameters on Ejection Volume in Electrohydrodynamic Jet Printing. Micromachines 9, 522 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Synthesis of monodisperse silver nanoparticles for ink-jet printed flexible electronics. Nanotechnology 22, 425601 (2011).

Vaseem, M., Lee, K. M., Hong, A.-R. & Hahn, Y.-B. Inkjet Printed Fractal-Connected Electrodes with Silver Nanoparticle Ink. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 3300–3307 (2012).

Hwang, J.-Y. & Moon, S.-J. The Characteristic Variations of Inkjet-Printed Silver Nanoparticle Ink During Furnace Sintering. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13, 6145–6149 (2013).

Ryu, K., Moon, Y.-J., Park, K., Hwang, J.-Y. & Moon, S.-J. Electrical Property and Surface Morphology of Silver Nanoparticles After Thermal Sintering. J. Electron. Mater. 45, 312–321 (2016).

Wang, D.-Y., Chang, Y., Wang, Y.-X., Zhang, Q. & Yang, Z.-G. Green water-based silver nanoplate conductive ink for flexible printed circuit. Mater. Technol. 31, 32–37 (2016).

Fernandes, I. J. et al. Silver nanoparticle conductive inks: synthesis, characterization, and fabrication of inkjet-printed flexible electrodes. Sci. Rep. 10 (2020).

Hussain, A. et al. Temperature Estimation during Pulsed Laser Sintering of Silver Nanoparticles. Appl. Sci. 12, 3467 (2022).

Merilampi, S., Laine-Ma, T. & Ruuskanen, P. The characterization of electrically conductive silver ink patterns on flexible substrates. Microelectron. Reliab. 49, 782–790 (2009).

Yang, M. et al. Mechanical and environmental durability of roll-to-roll printed silver nanoparticle film using a rapid laser annealing process for flexible electronics. Microelectron. Reliabil. 54 (2014).

Cai, Y. et al. Large-scale and facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles via a microwave method for a conductive pen. RSC Adv. 7, 34041–34048 (2017).

Li, C. et al. A two-step method to prepare silver nanoparticles ink for improving electrical and mechanical properties of printed silver wire. Mater. Express 11, 516–523 (2021).

Mo, L. et al. Silver Nanoparticles Based Ink with Moderate Sintering in Flexible and Printed Electronics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2124 (2019).

Cantor, B. in The Equations of Materials Ch. 7, 141-161 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Vollath, D., Fischer, F. D. & Holec, D. Surface energy of nanoparticles – influence of particle size and structure. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 9, 2265–2276 (2018).

Babalola, B. J., Ayodele, O. O. & Olubambi, P. A. Sintering of nanocrystalline materials: Sintering parameters. Heliyon 9, e14070 (2023).

Kothari, N. C. The effect of particle size on sintering kinetics in alumina powder. J. Nucl. Mater. 17, 43–54 (1965).

Demirskyi, D., Agrawal, D. & Ragula, A. A scaling law study of the initial stage of microwave sintering of iron spheres. Scr. Materialia 66, 323–326 (2012).

Herring, C. Effect of Change of Scale on Sintering Phenomena. J. Appl. Phys. 21, 301–303 (1950).

Liu, Z. et al. Enhanced Electrical and Mechanical Properties of a Printed Bimodal Silver Nanoparticle Ink for Flexible Electronics. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 215, 1800007 (2018).

Lee, I., Kim, S., Yun, J., Park, I. & Kim, T.-S. Interfacial toughening of solution processed Ag nanoparticle thin films by organic residuals. Nanotechnology 23, 485704 (2012).

Kim, B.-J. et al. Improving mechanical fatigue resistance by optimizing the nanoporous structure of inkjet-printed Ag electrodes for flexible devices. Nanotechnology 25, 125706 (2014).

Huang, Y. et al. Study effects of particle size in metal nanoink for electrohydrodynamic inkjet printing through analysis of droplet impact behaviors. J. Manuf. Process. 56, 1270–1276 (2020).

Jiang, L. et al. High-Sensitivity Fully Printed Flexible BaTiO3- Based Capacitive Humidity Sensor for In-Space Manufacturing by Electrohydrodynamic Inkjet Printing. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 24659–24667 (2024).

Smits, F. M. Measurement of Sheet Resistivities with the Four-Point Probe. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 37, 711–718 (1958).

Acknowledgements

C.G. would like to thank the support of the Boeing Fund for the Advancement of Undergraduate Research Excellence in Engineering. The authors also thank Liangkui Jiang and Dr. Hantang Qin for their assistance in assembling and repairing the EHD printer, and Farshid Noormohammadi and Govinda Ghimire from Dr. Patrick Johnson’s lab for their assistance in preparing a system to automatically record data for long-term cyclic bend testing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. conceived the bending test, designed the device, synthesized nanoparticles, performed electrical and mechanical testing, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. A.B. performed synthesis, sample preparation, and measurements for the revision. M.M. carried out printing experiments and characterization for the revision. C.G. assisted with device design, developed automated testing code, and contributed to revision. F.L. developed the initial synthesis protocol and contributed to revision. S.J. conceived the research concept, designed experiments, analyzed data, secured funding, supervised the project, and co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirscht, T., Bera, A., Marander, M. et al. Smaller is better: reducing silver nanoparticle size without excess ligands enhances conductivity and flexibility in printed thin films. npj Flex Electron 9, 113 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00496-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00496-3