Abstract

Previous studies link lower physical activity with incident Parkinson’s disease (PD) but rely on self-reported data and fail to address reverse causation. This study used accelerometer-derived daily step count, an objective measure of physical activity, to examine its association with incident PD in the UK Biobank, within successive periods of follow-up. PD cases were identified through hospital inpatient and death data, and associated with machine learning-derived step counts using Cox regression models, adjusted for age, sex, demographic and lifestyle factors. For 94,696 valid participants and a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 407 incident PD cases occurred. Every 1000 steps higher were associated with 8% lower risk of PD (hazard ratio 0.92, 95% confidence interval 0.89–0.94). However, this association was no longer statistically significant when excluding follow-up periods closer to the time of accelerometer wear, suggesting that low activity may be an early marker, but not a risk factor for PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent and most rapidly growing neurodegenerative disorder1,2, with an estimated prevalence of 9.4 million3 cases in 2020, marking a substantial increase from 5.2 million cases in 20044. The prodromal phase of PD has many well-recognised motor-related symptoms, such as subtle motor dysfunction, that are believed to occur over a decade before diagnosis5. Recognising these early indicators could provide crucial insights for improved disease understanding and may offer the possibility of identifying modifiable risk factors for developing PD.

In existing literature, low self-reported physical activity has been associated with a higher risk of incident PD6,7. Despite these observations, uncertainties remain, stemming from a reliance on self-report measurements of physical activity, which are crude and less reliable, creating greater uncertainties in observed associations8,9. In addition, PD’s progressive and prolonged development poses challenges in distinguishing between incident and prevalent cases. This ambiguity can introduce reverse-causation bias, where the observed associations may be influenced by the change in behaviour of individuals who already have underlying PD, rather than vice-versa. One common approach to mitigate potential reverse causation is to exclude the first few years of follow-up data. In PD studies, there is inconsistency around the number of years removed across studies, ranging between four to ten years, however, reduced activity levels were still significantly associated with incident PD after this exclusion6.

Daily step counts serve as a valuable proxy for measuring physical activity levels. One of the primary advantages of using average daily steps over other physical activity metrics is their simplicity, allowing for clear communication and understanding among the general population. This ease of interpretation helps in translating research findings into effective public health messaging10. Existing research into the association between physical activity and incident PD have typically used metabolic equivalent of task (MET) scores to estimate physical activity6. However, the increasing adoption of wearable devices, capable of estimating step counts, has encouraged research on their accuracy and reliability, particularly in populations diagnosed with PD11,12. The translatable nature of daily step counts encourages the expansion of this research into incident PD, allowing for results to offer insight into public health recommendations for potential disease prevention.

We, therefore, aimed to investigate the association between accelerometer-measured daily step counts and incident Parkinson’s disease, and how this association changed with latter windows of follow-up.

Results

Participant characteristics

After exclusions, this study consisted of 94,696 UK Biobank physical activity monitoring study13 participants (Fig. 1).

As shown in Table 1, among these participants, 56% were female, 97% identified as White. Most were in the least to second least deprived TDI quintile (<−1.509), compared to the TDI distribution of the general UK population in 201114. Those with step counts in the highest quintile (12,369+ daily steps) were younger, and had lower BMI compared to those in the lowest step count group (<6276 daily steps).

The overall mean of median daily steps calculated in the study population was 9446 steps and the standard deviation was 3822 steps. Participants with prevalent PD (n = 150), who were excluded from the study, exhibited the lowest average step count, as compared to incident and non-PD participants. Among those with incident PD, average median daily step counts were progressively higher with longer follow-up time from accelerometer wear to the first reporting of PD in their health records. Despite this, the average median daily steps in the incident PD population remained lower than that of non-PD participants, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Association of daily steps with incident Parkinson’s disease

Participants had a median follow-up time of 7.9 years (IQR: 7.4, 8.4), during which 407 incident PD cases occurred, with a median time to diagnosis of 5.2 years (IQR: 3.1, 6.8). We observed a strong and significant inverse linear association between median daily step quintiles and incident PD using data from the entire duration of follow-up (Fig. 2). Those who walked over 12,369 steps daily had a 59% lower risk of PD (HR 0.41; group specific 95% CI: 0.31–0.54), compared to those walking less than 6276 steps daily (HR 1.00; group-specific 95% CI: 0.84–1.19), after multivariable adjustment. There was no evidence of departure from linearity (p = 0.65).

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% group-specific confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using age as a timescale, adjusted for season of wear, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index, geographic region, education, employment, alcohol intake, smoking status and coffee intake. HR is above, and the number of events is plotted below each data point. The HR (95% CI) per 1000 additional daily steps is 0.92 (0.89–0.94).

For the multivariable model, every 1000 daily steps higher was associated with an 8% lower risk of PD (HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.89–0.94). The sequential adjustment of covariates from the univariable to multivariable model showed minimal changes to the strength of the association and the chi-squared increased by 33% (shown in the supplementary material). The further adjustment of additional covariates minimally altered the observed associations. However, adjustment for sleep duration did attenuate the strength of association, with a reduction in the chi-squared by 64%, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Furthermore, we observed no significant difference across subgroups, including age groups, sex, BMI status and history of depression. After removing 9734 individuals with prevalent neurological cases, the observed association was similar to that observed in our main study sample (HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.89–0.95).

To address potential reverse causality, we assessed how the association between step counts and PD risk may have changed over follow-up periods of <2, 2–4, 4–6 and 6+ (Fig. 3). We observed the strongest association within the first two years of follow-up (HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.70–0.90), during which there were 55 incident cases (Fig. 3). However, the association was attenuated for later windows of follow-up, trending towards not statistically significant. This is despite having higher relative numbers of cases in latter periods of follow-up, reducing uncertainty in estimates. For the follow-up period of over 6 years, the HR was no longer statistically significant, with a hazard of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.92–1.01).

These findings remained consistent after running a sensitivity analysis using a step count algorithm trained on both healthy and PD populations. The estimate median daily step counts between the two algorithms, healthy and PD-trained compared to healthy-only trained, showed very strong correlation, with a Pearson correlation coefficient15 of 0.97, as seen in Supplementary Fig. 6. Furthermore, a significant association was found between PD-trained median daily step count and incident PD using all periods of follow-up, with covariate adjustment, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8. As seen previously, this HR, however, was no longer statically significant when considering follow-up periods of over 6 years (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.92–1.00).

Discussion

Higher accelerometer-derived physical activity levels, indicated by median daily step counts, were associated with a lower risk of incident Parkinson’s disease (PD) when using data from all periods of follow-up. This association remained statistically significant after multivariable adjustment, investigating potential confounding factors, and among subpopulations of interest. However, this association was no longer statically significant when considering later periods of follow-up, indicating that reverse causation bias is likely.

Our findings are in contrast to some previous literature in the field that supports an association between physical activity levels and incident PD, even after the consideration of reverse causation6,16,17,18. In a meta-analysis of this association with a median (range) follow-up of 12 (6.1–22.0) years, the relative risk for incident PD comparing the highest and lowest categories of total physical activity was 0.79 (95% CI 0.68–0.91), and remained significant when the first four to ten years of follow-up was removed from the constituent studies (0.76; 95% CI 0.64–0.91)6. In our study, removing years of follow-up reduced the strength of the observed association. Similar attenuations between physical activity and diseases of ageing have been reported in other studies. Our findings are more consistent with results from a study on physical activity and dementia that was conducted in the Whitehall Study and Million Women Study19,20.

These results, however, support existing literature in finding lower physical activity levels to be a strong indicator/feature of prodromal or early PD18,21. One study reported that this reduction in activity may occur up to 4 years before a clinical diagnosis18. A separate study assessing minutes of daily physical activity21 found a reduction of 29% in comparing clinical PD participants to controls, in minutes of daily physical activity. There are several hypotheses for these activity changes, including changes in overall disability, poorer walking performance, and fear of falls/anxiety/depression21. It should be noted, however, that this reduction in activity is not fully explained by known factors, with this study encouraging further research into explaining this behaviour21.

Our study has several strengths. First, we used objective measures of activity derived from accelerometer data, which offers greater reliability in the measurement of this exposure compared to questionnaire-based studies. Second, the use of step count as a measure of daily physical activity offers the opportunity for better communication as step counts are easily translatable for public health messaging. Next, this work has built on previous studies investigating PD using the UK Biobank physical activity monitoring study16,17,22, however with longer follow-up, while also addressing some of these studies’ limitations. Of these limitations, we explored how the association may change over follow-up periods to better describe the potential impact of reverse causation.

There are also some limitations to our study. Firstly, this analysis was purely observational; hence we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured or residual confounding in the observed associations, despite considering a comprehensive set of confounders. Secondly, the UK Biobank provides limited health data linkage for participants, which we use to identify participants with PD. We use the approach recommended by UK Biobank to ascertain PD, combining hospital inpatient, death register and self-reported data23, which may tend to identify more severe cases. These records do not provide information regarding the severity or subtype of PD, which may offer further insights into this association. Furthermore, primary care data could bolster PD cases, but is currently limited to just 45% of participants and only up to 201713. Lastly, this study is limited by the number of cases observed within period of follow-up. With 407 incident cases of PD from all periods of follow-up, and just 156 diagnosed at least 6 years after participating in the study, we are somewhat limited in power to observe small effects of greater activity. We are also limited by a maximum follow-up time of 9.4 years. The PD prodromal window is typically reported to be at least 10 years prior to a clinical diagnosis5.

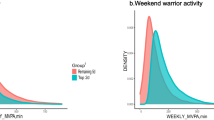

Future studies in this population can benefit from higher case numbers from a longer follow-up period, while also giving further insights into this association, beyond the prodromal window of PD. Further investigations should also explore the association between other accelerometer-derived metrics and incident PD, such as metrics relating to gait speed, stride length or the distribution of steps throughout the week. Furthermore, we would encourage similar analyses in other study populations, such as the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI)-Verily study24,25, containing a higher proportion of individuals with prodromal PD, and the All of Us study26, containing greater diversity in race, ethnicity and socio-economic status.

Results from this prospective study add to the literature on physical activity and incident PD, suggesting that higher daily step counts were associated with lower risk of incident PD, but only for short follow-up periods. Therefore, the observed association may be explained by reverse causation bias. This work supports the continued labelling of low physical activity as a marker for Parkinson’s disease, rather than as a risk factor leading to Parkinson’s disease.

Methods

Study cohort

The UK Biobank is a prospective cohort study of 502,536 adults in the United Kingdom who were recruited between 2006 and 2010. The consented participants completed a questionnaire, interview, and provided physical measurements, as well as blood, urine, and saliva samples27,28. A subgroup of participants consented to wear an Axivity AX3 wrist-worn accelerometer for up to 7 days between 2013 and 201513. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the National Information Governance Board for Health and Social Care and the National Health Service North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (06/MRE08/65).

Accelerometer-derived physical activity processing

Accelerometer data was processed to derive step counts using the OxWearables “stepcount” package (version 2.1.5), a hybrid self-supervised machine learning model that was trained on ground truth free-living data and counts peaks in detected walking windows of behaviour29. Steps were predicted for each participant’s full period of collected data, with missing periods due to non-wear imputed by averaging the step counts in the corresponding times across valid days29. We then calculated the median of the imputed daily step counts, across the period of monitoring, as the primary exposure in this study.

Ascertainment of Parkinson’s disease

The diagnosis of PD was obtained from a combination of the UK Biobank’s linked hospital data; inpatient hospital admissions data, and death data. Diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (version 10) coding system, with outcomes recorded as the first instance of a G20 diagnostic code23. This follows the approach recommended by the UK Biobank23, and used by other studies in studying PD in the physical activity monitoring cohort16,17,22. Incident PD however was defined at their first diagnosis of PD. Participants were censored at the first date of PD diagnosis, date of death, or at the end of their follow-up period (31 October 2022 for England, 31 August 2022 for Scotland, and 31 May 2022 for Wales), whichever came first30.

Statistical analysis

We processed the accelerometer data from 103,660 participants. We excluded participants with device calibration or data reading errors (>1% of values outside +/-8g range), and those whose data could not be processed. In addition, participants were excluded due to inadequate wear time, either less than 72 h of detected wear, or non-wear at a particular time of day for all days of monitoring. We did not implement any day level exclusions, to remove any data due to insufficient wear on a given day. Further exclusions were made for unreasonably high average acceleration (>100 mg).This exclusion criteria aligns with numerous existing studies on this dataset22,29,31,32. We also excluded all 150 prevalent PD and 22 other Parkinsonism cases, diagnosed before accelerometer wear, and participants with missing healthcare linkages or covariate data. The final analysis included 94,696 participants (Fig. 1).

A Cox proportional hazard regression model33 was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between daily step counts and incident PD. The association was first evaluated using quintiles of median daily step count. CIs when using quintiles of daily steps as the primary exposure were estimated using floating absolute risk, to represent group-specific variances in hazard, therefore referred to as group-specific CIs34.

We then evaluated how the risk of PD was associated with each 1000 steps per day higher. We sequentially applied the full set of adjustments to the multivariable model. The impact of these sequential adjustments were assessed using chi-squared test. Specifically, for the per-1000 median daily steps with one degree of freedom, we compared the chi-squared values before and after adjustment. A likelihood ratio test comparing quintiles of daily steps as categorical and ordinal was performed to test that the association between daily steps and incident PD did not significantly depart from linearity35. This allows for the reporting of hazard ratios per 1000 steps rather than quintiles of step count. At each step of this sequential adjustment, confounding was assessed by observing the chi-squared from a likelihood ratio test of the association.

Multivariable models used age as the time scale, as age was a strong potential confounder in this analysis36,37. These models were adjusted for the following covariates: season of device wear (spring, summer, autumn, winter), sex (female, male), ethnicity (white, non-white), Townsend Deprivation Index (TDI, stratified by quintiles in UK population14), geographic region of assessment centre (London, Midlands, Yorkshire, Northeast, Northwest, Southeast, Southwest England, Scotland, Wales), educational attainment (degree, diploma, A/AS levels, professional qualification, GCSE/O levels, no degree/qualification), employment status (employed, not employed), smoking status (never, previous, current) and alcohol consumption (never, <3 times per week, ≥3 times per week) and coffee intake (non-drinker, ≤2 cups a day, >2 cups a day). We adjusted for season of device wear as a technical covariate, which explains part of the variation in physical activity levels38. The remaining covariates were chosen as known risk factors for PD, particularly those from the PREDICT-PD risk model36, with possible association to physical activity, and reliable and accurate recording in UK Biobank records, while not hypothesised to be on the causal pathway36,39. All covariate data were provided by participants at the UK Biobank baseline assessment visit, with details provided in Supplementary Table 2. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals40, and no violations were observed.

We conducted several orthogonal analyses using the models assessing the risk for each 1000 daily steps higher. First, we expanded our multivariable-adjusted models by additionally adjusting for body mass index (BMI) at baseline, depression, type 2 diabetes, constipation, bladder dysfunction derived through a combination of self-report and health records, and sleep duration derived from accelerometer data. These covariates were chosen as known health-related PD risk factors with an association with physical activity, that were hypothesised possibly be on the causal pathway5,36,41. We then explored whether the observed associations differed within subpopulations of interest, including by age groups, sex, BMI (<25, 25–30, 30+ kg/m2)42 and history of depression. Additionally, we performed a sensitivity analysis examining the associations after excluding participants with any history of neurological disorder. To assess potential reverse causation and evaluate how associations changed over time, we estimated HRs within successive follow-up intervals (0–2, 2–4, 4–6, and ≥6 years) using Lexis expansion43,44. For each participant, total follow-up time was divided into these intervals, generating one record for each period in which the individual contributed person-time. Each record represented time at risk within that interval, with follow-up left-truncated at the start and right-censored at the end of the interval. HRs were then estimated separately for each interval to assess temporal changes in the associations, following a similar approach to that described by Floud et al.20.

We also performed a final sensitivity analysis, to ensure the model could reliably detect steps in individuals at-risk of incident PD. To do so, we modified the stepcount algorithm deployed on the UK Biobank population, so that instead of only being trained on the healthy OxWalk population, it was additionally trained on the Michael J. Fox Foundation Levodopa Response (MJFF-LR) dataset45, consisting of wrist-worn accelerometer data collected from 28 clinical PD individuals. The full association analysis pipeline was then re-run, using this PD-trained stepcount algorithm, to observe how this may affect our findings.

Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.3.2, using Cox regression models from the survival package, version 3.8-3. Results were reported according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (Supplementary Table 3)46.

Data availability

This study uses UK Biobank data, available at: [https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/apply-for-access].

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available in Github and can be accessed via this link https://github.com/OxWearables/steps_PD.

References

Mhyre, T. R., Boyd, J. T., Hamill, R. W. & Maguire-Zeiss, K. A. Parkinson’s disease. Subcell. Biochem. 65, 389–455 (2012).

Dorsey, E. R. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of parkinson’s disease, 1990– 2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 17, 939–953 (2018).

Maserejian, N., Vinikoor-Imler, L. & Dilley, A. Estimation of the 2020 Global Population of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) (MDS Abstracts, 2020).

Ahlrichs, C. & Lawo, M. Parkinson’s Disease Motor Symptoms in Machine Learning: A Review. HIIJ (2013).

Postuma, R. B. & Berg, D. Advances in markers of prodromal Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12, 622–634 (2016).

Fang, X. et al. Association of levels of physical activity with risk of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e182421 (2018).

LaHue, S. C., Comella, C. L. & Tanner, C. M. The best medicine? The influence of physical activity and inactivity on Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 31, 1444–1454 (2016).

Sallis, J. F. & Saelens, B. E. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc. Sport 71, 1–14 (2000).

Shephard, R. J. Limits to the measurement of habitual physical activity by questionnaires. Br. J. Sports Med. 37, 197 (2003).

Bassett, D. R., Toth, L. P., LaMunion, S. R. & Crouter, S. E. Step counting: a review of measurement considerations and health-related applications. Sports Med. Auckl. Nz 47, 1303–1315 (2017).

Shokouhi, N., Khodakarami, H., Fernando, C., Osborn, S. & Horne, M. Accuracy of step count estimations in Parkinson’s disease can be predicted using ambulatory monitoring. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.904895 (2022).

Bianchini, E. et al. Four days are enough to provide a reliable daily step count in mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease through a commercial smartwatch. Sensors 23, 8971 (2023).

Doherty, A. et al. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: the UK Biobank study. PLOS One 12, e0169649 (2017).

Yousaf, S. & Bonsall, A. UK Townsend Deprivation Scores from 2011 census data. https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/statistics.digitalresources.jisc.ac.uk/dkan/files/Townsend_Deprivation_Scores/UK%20Townsend%20Deprivation%20Scores%20from%202011%20census%20data.pdf (2017).

11. Correlation and regression. BMJ, https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/statistics-square-one/11-correlation-and-regression (2025).

Zhao, A., Cui, E., Leroux, A., Lindquist, M. A. & Crainiceanu, C. M. Evaluating the prediction performance of objective physical activity measures for incident Parkinson’s disease in the UK Biobank. J. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11939-0 (2023).

Liu, M. et al. Association of accelerometer-measured physical activity intensity, sedentary time, and exercise time with incident Parkinson’s disease. Npj Digit Med. 6, 224 (2023).

Xu, Q. et al. Physical activities and future risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 75, 341–348 (2010).

Sabia, S. et al. Physical activity, cognitive decline, and risk of dementia: 28 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ 357, j2709 (2017).

Floud, S. et al. Body mass index, diet, physical inactivity, and the incidence of dementia in 1 million UK women. Neurology 94, e123–e132 (2020).

van Nimwegen, M. et al. Physical inactivity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 258, 2214–2221 (2011).

Schalkamp, A. K., Peall, K. J., Harrison, N. A. & Sandor, C. Wearable movement-tracking data identify Parkinson’s disease years before clinical diagnosis. Nat. Med. 29, 2048–2056 (2023).

Bush, K., Rannikmae, K., Wilkinson, T., Schnier, C. & Sudlow, C. Definitions of Parkinson’s Disease and the Major Causes of Parkinsonism, UK Biobank Phase 1 Outcomes Adjudication. https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/alg_outcome_pdp.pdf (2018).

Marek, K. et al. The Parkinson’s progression markers initiative (PPMI) - establishing a PD biomarker cohort. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 5, 1460–1477 (2018).

Dorsey, E. R. & Marks, W. J. Jr. Verily and Its Approach to Digital Biomarkers. Digit Biomark. 1, 96–99 (2017).

Bailey, C. P. et al. Fitbit physical activity and sleep data in the all of us research program: data exploration and processing considerations for research. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003804 (2025).

UK Biobank. UK Biobank Enable your research. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research (2024).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLOS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Small, S. R. et al. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Wrist-Worn Step Detection Algorithm with Deployment in the UK Biobank. Public and Global Health https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.20.23285750 (2023).

UK Biobank. UK Biobank. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk (2024).

Walmsley, R. et al. Reallocation of time between device-measured movement behaviours and risk of incident cardiovascular disease. Br. J. Sports Med. 56, bjsports-2021-104050. (2021)

Doherty, A. et al. GWAS identifies 14 loci for device-measured physical activity and sleep duration. Nat. Commun. 9, 5257 (2018).

Cox, D. R. Regression models and life-tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 34, 187–220 (1972).

Easton, D. F., Peto, J. & Babiker, A. G. Floating absolute risk: an alternative to relative risk in survival and case-control analysis avoiding an arbitrary reference group. Stat. Med. 10, 1025–1035 (1991).

Kirkwood B. R. & Sterne J. A. C. Essential Medical Statistics (John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2003).

Noyce, A. J. et al. PREDICT-PD: identifying risk of Parkinson’s disease in the community: methods and baseline results. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 85, 31–37 (2014).

Reeve, A., Simcox, E. & Turnbull, D. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: why is advancing age the biggest risk factor? Ageing Res Rev. 14, 19–30 (2014).

Turrisi, T. B. et al. Seasons, weather, and device-measured movement behaviors: a scoping review from 2006 to 2020. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 18, 24 (2021).

Najafi, F. et al. Association between socioeconomic status and Parkinson’s disease: findings from a large incident case–control study. BMJ Neurol. Open 5, e000386 (2023).

Schoenfeld, D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika 69, 239–241 (1982).

Dommershuijsen, L. J., Boon, A. J. W. & Ikram, M. K. Probing the pre-diagnostic phase of Parkinson’s disease in population-based studies. Front. Neurol. 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.702502 (2021).

Weir, C. B. & Jan, A. BMI classification percentile and cut off points. In: StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing; 2023). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541070/

Plummer, M. & Carstensen, B. Lexis: an R class for epidemiological studies with long-term follow-up. J. Stat. Softw. 38, 1–12 (2011).

Hong, L. S. & Lewington, S. Lexis expansion- age-at-risk adjustment for survival analysis. https://www.lexjansen.com/phuse/2013/sp/SP09.pdf (2013).

Snyder P., Tummalacherla M. MJFF Levodopa response study. https://doi.org/10.7303/SYN20681023 (2019).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Sarah Floud and Tonima Trisa for their guidance in the handling of reverse causation in this association. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 59070. This research is supported by the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Health Data Science [EP/S02428X/1], and by GSK plc as part of an iCase studentship [EP/V519741/1]. AD and SvD are supported by the Wellcome Trust [223100/Z/21/Z]. AD and DB are supported by Novo Nordisk. AD, CH, and DB are supported by SwissRe. CZ and AD are supported by the Oxford BHF Centre of Research Excellence [RE/18/3/34214]. DC is supported by the Pandemic Sciences Institute at the University of Oxford; the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC); an NIHR Research Professorship; a Royal Academy of Engineering Research Chair; the Wellcome Trust funded VITAL project [204904/Z/16/Z]; the EPSRC [EP/W031744/1]; and the InnoHK Hong Kong Centre for Cerebro-cardiovascular Engineering (COCHE). AS is supported by the National Institutes of Health’s Intramural Research Program and by the National Institutes of Health’s Oxford Cambridge Scholars Program. CA is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and has received research grant support from UCB Pharma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A., A.C., D.C. and A.D. contributed to the conception and design of the project. A.A. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the figures, with critical input and guidance from C.H., A.S. and C.Z. A.A., A.C., V.H., A.S., C.Z., C.H., S.vD., C.A., D.B., D.C. and A.D. contributed to manuscript revisions, reviewed the final version, and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.S., C.Z., C.H., S.vD., C.A. and D.B. declare no competing interests. A.A., A.C. and D.C. were supported by GSK during this research. V.H. is an employee at GSK. A.D. has received research grants from SwissRe and Novo Nordisk. A.A., A.C. and A.D. have released the stepcount package software under an academic use licence that could result in commercial entities paying license fees for their use. The funders/sponsors had no role in the design of this study or the analysis and interpretation of the results.This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contributions of the NIH author(s) are considered Works of the United States Government. The findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Acquah, A., Creagh, A., Hamy, V. et al. Daily steps are a predictor of, but perhaps not a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease: findings from the UK Biobank. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01214-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01214-6