Abstract

Primary care clinicians play a key role in asthma and asthma exacerbation management worldwide because most patients with asthma are treated in primary care settings. The high burden of asthma exacerbations persists and important practice gaps remain, despite continual advances in asthma care. Lack of primary care-specific guidance, uncontrolled asthma, incomplete assessment of exacerbation and asthma control history, and reliance on systemic corticosteroids or short-acting beta2-agonist-only therapy are challenges clinicians face today with asthma care. Evidence supports the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) + fast-acting bronchodilator treatments when used as needed in response to symptoms to improve asthma control and reduce rates of exacerbations, and the symptoms that occur leading up to an asthma exacerbation provide a window of opportunity to intervene with ICS. Incorporating patient perspectives and preferences when designing asthma regimens will help patients be more engaged in their therapy and may contribute to improved adherence and outcomes. This expert consensus contains 10 Best Practice Advice Points from a panel of primary care clinicians and a patient representative, formed in collaboration with the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG), a clinically led charitable organization that works locally and globally in primary care to improve respiratory health. The panel met virtually and developed a series of best practice statements, which were drafted and subsequently voted on to obtain consensus. Primary care clinicians globally are encouraged to review and adapt these best practice advice points on preventing and managing asthma exacerbations to their local practice patterns to enhance asthma care within their practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma exacerbations (also referred to as “flare-ups” or “attacks”) are characterized by a sudden or progressive worsening of symptoms including wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, cough, and decline in lung function. These are an alteration from the patient’s usual condition, necessitating a change in therapy1. Asthma exacerbations are a significant cause of disease-related morbidity, and mortality, progressive loss of lung function, and increased health care costs globally2. Some data over the past decades show reductions in age-adjusted asthma mortality, while asthma incidence remains steady or slightly increased (Fig. 1). Asthma exacerbation rate data are inconsistent, with some showing increased exacerbations and some showing decreased exacerbations in recent years3,4, but emergency department (ED) visits for asthma remain a significant challenge5,6. Further, asthma exacerbations may be underreported as they are not always medically treated or reported7.

SDI, sociodemographic index. Reproduced without modification from: Cao Y, et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1036674 under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

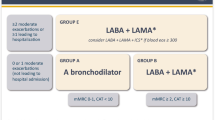

Primary care clinicians (PCCs) play an integral role in preventing and managing asthma exacerbations and most patients can be successfully managed in primary care worldwide1,8,9,10. Enhancing prevention and management of asthma exacerbations in primary care settings would be expected to further lower asthma morbidity and potentially mortality. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) report includes an algorithm for exacerbation recognition and management in primary care, which can facilitate implementation of practical step-by-step strategies to deal with exacerbations (Fig. 2)1.

Source: From GINA ©2024 Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Available from www.ginasthma.org.

This international expert consensus seeks to develop practice-specific recommendations for asthma exacerbation diagnosis and management for primary care by building on available resources including GINA, Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) in the United States, guidance from the Japanese Society of Allergology, and the Australian Asthma Handbook, among others1,10,11,12,13,14. The consensus best practice statements are listed in the Table 1 and further explored below.

Methods

A multi-nation expert panel of individuals with expertise and experience in asthma management in primary care practice was assembled. The panel included clinicians from the United States, Australia, Spain, and Portugal, and a patient advocate. The panel was formed in collaboration with the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG), a clinically led charitable organization that works locally and globally in primary care to improve respiratory health. IPCRG’s 155,000+ members are based in 40 different countries. The panel met virtually and developed a series of best practice statements, which were drafted and subsequently voted on to obtain consensus. To reach consensus, the expert panel members participated in a survey, requiring a predefined threshold of 75% approval for each Best Practice Advice point. An initial failure to reach consensus was resolved by subsequent discussions, revisions as needed, and re-voting.

Identify and Assess Asthma Exacerbations

Best Practice Advice 1: Consider incorporating available validated tools into primary care settings to evaluate asthma status including symptom burden, exacerbation history, and risk

Assessing asthma control is fundamental for asthma management to optimize medication therapy, prevent exacerbations, improve quality of life and achieve patient and clinical treatment goals1,15. Clinicians’ and patients’ assessment of asthma control tends to overestimate control and often differ from each other. Validated tools can help improve the accuracy of assessment of asthma control16. However, most validated tools assess only symptoms (shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, chest tightness or pain) with little or no attention to past exacerbations and therefore the risk of exacerbations (also called “asthma attacks”) which is also a key factor in a patient’s overall asthma control17.

An ideal tool for assessing asthma control should include questions that reveal both symptoms and exacerbation risk, such as the Asthma Impairment and Risk Questionnaire (AIRQ)18,19. Prior exacerbations are the best predictor of future exacerbations, which is one reason the AIRQ contains questions focusing on exacerbation history.

Validated asthma assessment tools include the following:

-

AIRQ. The AIRQ is a recently developed and validated 10 “yes/no” question tool that incorporates both symptom and exacerbation risk assessment17,18. Scores range from 0–10, with a score of 0–1 indicating well-controlled asthma and higher scores representing worsening asthma control18. AIRQ control level has been found to predict risk of future exacerbations over the following 12 months19. The assessment tool is linked to suggestions for further evaluation of each question domain. Between annual visits, a follow-up version of AIRQ can be used to assess ongoing disease status and the impact of interventions20.

-

○

Link to AIRQ: https://www.asthmaresourcecenter.com/home/for-your-practice.html

-

○

-

Asthma APGAR. The Asthma APGAR includes 6 questions with 2-week recall; the 3 multi-answer questions address symptoms and activity limitations and are scored with the other 3 to identify potential reasons for lack of control. Scores of >2 are considered inadequate control. It is linked to a care algorithm based on NAEPP guidelines21,22.

-

○

Link to Asthma APGAR questions and care algorithm: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/nrn/nrn19-asthma-apgar.pdf.

-

○

-

Asthma Control Test (ACT). The ACT includes 5 multi-answer questions about symptoms, activity limitations, rescue inhaler use and patient perception of control with 4-week recall. Scores range from 5–25 with higher scores indicating better control23. A score of 20–25 indicates well-controlled asthma, and the maximum clinically important difference is 3 points24.

-

○

Link to ACT questions: https://www.asthmacontroltest.com/welcome

-

○

-

Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ). The ACQ includes 5 symptom-based questions with 4-week recall1,25. Scores range from 0–6, with higher scores indicating worse asthma control; the total score is an average of individual items1.

-

○

Link to obtain ACQ: https://www.qoltech.co.uk/acq.html

-

○

-

Control of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma Test (CARAT). CARAT is a 10-question patient‐reported outcome measurement (PROM) assessing the control of asthma and allergic rhinitis at a 4-week interval. Scores range from 0 to 30. Scores higher than 24 indicate good disease control26. There are separate scores for asthma and allergic rhinitis.

-

○

Link to obtain CARAT: https://www.new.caratnetwork.org/fastcarat/index.html

-

○

The GINA report includes a suggestion for 4 areas to be covered when assessing control. The questions are not validated but are a good guide to what to ask if a validated questionnaire is not used.

-

Link to GINA questions: (page 15) https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Main-pocket-guide_2020_04_03-final-wms.pdf

Using validated tools in practice requires planning to implement but has been reported to save clinician time in continuity of care22. Practical implementation strategies might include asking patients to complete questions before seeing the clinician, with assistance from the receptionist, rooming staff, or an online portal. The clinician will then be able to quickly review the results and incorporate them into treatment decisions, without using time during the appointment to conduct the assessment. The validated tools and GINA questions can ensure the needed information is obtained, compared to asking less useful questions such as “How is your asthma?” Scores can be followed over time to assess treatment effectiveness. Mobile health apps may also be useful to facilitate asthma self-management and symptom awareness27.

Best Practice Advice 2: Counsel patients on the warning signs and symptoms of loss of asthma control that may precede exacerbations to facilitate initiation of timely and effective treatment to prevent exacerbations or reduce their severity

Counseling patient on warning signs such as an increase in their usual asthma symptoms or new onset of things such as cough that can precede exacerbations could prompt treatment with anti-inflammatory therapy, help mitigate exacerbation severity, and potentially prevent an exacerbation from occurring2,28. Appropriate use of anti-inflammatory therapy (ICS) prior to an exacerbation may decrease use and overuse of health care resources such as the ED or urgent care, SABA and systemic corticosteroids (SCS).

Using an asthma action plan can give patients and families specific parameters for patients to take action in identifying and using early treatment for an exacerbation29. Exacerbation triggers and how to address them should be identified.

While spirometry is the gold standard for diagnosing asthma it has limited practical value in exacerbation management1. Peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurement can provide objective data on lung function for assessing exacerbation severity and response to treatment30. However, frequency and severity of symptoms is a more practical and widely available measure of exacerbation onset and is more sensitive than PEF for most people31. For those with poor perception of airflow limitation symptoms, regular PEF monitoring can help proactively identify exacerbation episodes1,32.

Window of opportunity for intervention

About 10–14 days before an asthma exacerbation, progressively rising inflammation often underlies the decrease in lung function (PEF), accompanied by an increase in symptoms33,34, which may result in patients increasing SABA use34,35,36. SABA use can provide symptomatic relief, but it does not address airway inflammation and overuse of SABA has been shown to increase risks33,34. The timeframe leading up to an exacerbation may represent a “window of opportunity” to minimize airway inflammation and either prevent or reduce the exacerbation by adding anti-inflammatory therapy, if the patient is not using anti-inflammatory therapy, or scaling up the current anti-inflammatory dose.

GINA recommends the use of an anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR), which is low dose as-needed ICS-formoterol, or ICS-SABA for symptom control rather than SABA-only as a means to improve control and mitigate the risk of a serious exacerbation. Formoterol has the advantage of a fast and long-acting bronchodilator, while salbutamol (albuterol) is also fast but short-acting1.

Best Practice Advice 3: Recognize and support education and management plans addressing exacerbation risk for people with all severities of asthma

Asthma exacerbations can occur in all severities of asthma despite guideline-directed treatment2. A history of ED visits or hospitalization for an exacerbation increase the risk of future exacerbations, irrespective of severity, patient demographics, or clinical characteristics2,37. Patients with intermittent, mild, and moderate asthma are all at risk for exacerbations, which is often related to unrecognized lack of asthma control.

Recently in the US, approximately 60% of adults and 44% of children were reported to have uncontrolled asthma38,39, with more than 80% of whom had mild or moderate asthma40. In an international cohort of 1115 patients classified as GINA Step 1 or Step 2, 25% had uncontrolled asthma and about 33% reported rescue inhaler use in the previous 4 weeks1,41. Based on United Kingdom data from the National Review of Asthma Deaths, up to 45% of patients across asthma severities dies without seeking medical assistance or before emergency care could be provided, indicating a need for improved education and management plans42.

Appropriate and optimal therapy to minimize symptoms, exacerbations risk, and routine exacerbation assessment and history is important for all patients with asthma, regardless of severity.

Best Practice Advice 4: Evaluate adherence to prescribed therapy (target adherence ≥ 75%) and inhaler technique at all asthma related visits, asking non-judgmental questions, and provide education and support based on that evaluation

Although ICS are highly effective anti-inflammatory therapies for asthma, patients often demonstrate poor adherence to prescribed ICS-containing daily maintenance regimens43,44. Those with uncontrolled asthma and inadequate adherence are at the highest risk for adverse outcomes45. Adherence rates of ≥75% have been shown to significantly improve asthma control46. Assessing adherence can be accomplished using open ended non-judgmental questions such as “It is often hard to take an inhaler every day. How many times a week do you think you miss or forget or cannot take your asthma inhalers?”

Use of SABA-only inhalers for rescue or quick symptom relief can lead to overuse of SABA. The use of an ICS/fast-acting bronchodilator (SABA or fast-acting LABA [long-acting beta agonist]) has been shown to decrease exacerbations compared to the use of albuterol alone1,47,48,49,50.

Up to 80% of patients with asthma have incorrect inhaler technique, which may be associated with factors such as age, sex, education level and failure of patients to be shown proper technique51,52. Incorrect inhaler use has been linked to poor asthma outcomes such as more frequent ED visits and hospitalizations, prescriptions of SCS and antibiotics (overused in asthma exacerbation management), and worsened disease control51,53. Even after successful intervention to improve inhaler technique, patients may revert to incorrect use within a short time requiring repeated teaching and evaluation updates51,54.

Given the importance of correct inhaler technique for asthma control and exacerbation prevention, all healthcare professionals such as physicians, nurses, and pharmacists should be involved in the instruction and review of inhaler technique. Repeated assessment at each visit and education on correct methods is recommended and may yield benefits for individual patients without risk of harm1,51. Several resources are available to help teach inhaler technique.

-

IPCRG inhaler videos: https://www.ipcrg.org/resources/inhaler-resources

-

Australia National Asthma Council videos: https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/how-to-videos

Actively Address Asthma Exacerbation Management and Prevention

Best Practice Advice 5: Recognize the cumulative adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids (SCS) use and work to avoid their overuse by preventing future exacerbations

While some asthma exacerbations may require SCS1,10, earlier recognition and use of ICS with SABA or fast-acting LABA for quick relief or early in an exacerbation may mitigate the need for SCS. Rarely, if ever, are SCS required for effective maintenance management, and their use should be minimized where possible due to potential short-term and long-term adverse effects55.

Adverse effects resulting from SCS use occur based on cumulative lifetime dose, starting at doses as low as 500 mg of prednisone or equivalent and less than 30 days of exposure56. Adverse effects of SCS can occur with both chronic and repeated episodic use with cumulative doses ≥1000 mg of prednisone equivalent per year, regardless of the length of treatment. A common regimen for exacerbation management is prednisone (or equivalent) 40–60 mg for 5–10 days, adding up to a cumulative dose of 200–600 mg per exacerbation, approaching or exceeding the long-term effect risk threshold after even a single course of SCS1,10. Higher cumulative SCS doses are associated with increases in cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, fractures, cerebrovascular disease, pneumonia, kidney impairment, cataracts, sleep apnea, depression, anxiety, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain56,57,58,59.

To limit the use of SCS, PCCs can implement asthma treatment that appropriately uses ICS-based therapies in both acute and maintenance regimens, thereby reducing the risk of exacerbations and the need for SCS1,47. PCCs should include monitoring patients for adverse effects of corticosteroids, especially among those with multiple courses of SCS therapy over the years of their asthma care.

Best Practice Advice 6: Consider the use of AIR, MART (formerly known as SMART) or ICS-SABA quick reliever regimens for treating asthma and exacerbations to address underlying inflammation as well as provide bronchodilation

For patients requiring maintenance treatment (GINA Steps 3–5), maintenance-and-reliever therapy (MART), formerly known as single-inhaler maintenance-and-reliever therapy (SMART), is referred to by the GINA report as a “treatment regimen in which the patient uses an ICS-formoterol inhaler every day (maintenance dose), and also uses the same medication as needed for relief of asthma symptoms (reliever doses).”1 The clinical rationale for recommending MART, or a combination of ICS and fast-acting bronchodilator, is based on the increased risk of severe or fatal exacerbations with SABA-only use, as well as evidence showing a lower frequency of exacerbations with ICS + formoterol as maintenance and rescue therapy1,60,61,62,63,64,65,66.

For patients only requiring reliever treatment (Steps 1–2), GINA recommends the use of AIR, or low dose as-needed ICS-formoterol, as the preferred treatment (Track 1)1.

Use of ICS along with a SABA for rescue therapy can reduce exacerbations compared to SABA-only rescue therapy. In the PREPARE trial, adults with moderate-to-severe asthma who were instructed to take ICS every time they used rescue therapy had a lower annualized rate of severe exacerbations than those who weren’t instructed to take ICS with rescue therapy49. In the MANDALA randomized, double-blind trial, adults and adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma receiving albuterol-budesonide as rescue therapy had a significantly lower risk of severe asthma exacerbations than those receiving albuterol alone47. Of note, albuterol-budesonide is approved for the as-needed treatment or prevention of bronchoconstriction and to reduce the risk of exacerbations in patients with asthma 18 years of age and older in the United States.

The physiologic rationale for ICS use with bronchodilation to manage exacerbations is related to the more rapid nongenomic effects of ICS, which may not be widely known among clinicians. Historically clinicians were told that ICS time to onset of anti-inflammatory effects took days to occur. Recent evidence indicates a more rapid onset (minutes) of action of ICS due to the complementary mechanisms of nongenomic and genomic effects67,68.

Implementing AIR and MART for asthma management and exacerbations may be limited by national and local restrictions and product availability. PCCs are encouraged to increase awareness of available options for AIR and MART in their local areas, including the use of SABA-ICS as a combination inhaler. In areas where such products are unavailable, patients may be instructed to take a dose of ICS each time they use a SABA inhaler (ICS and SABA in separate inhalers), though this can be more cumbersome for patients1.

Additionally, some patients may receive their current asthma treatment primarily via nebulizer, which does not easily lend to AIR or MART but can be accommodated by ICS-SABA quick relief therapy. In general, nebulizers are not considered the best practice to deliver asthma treatment and should be discouraged. ICS/SABA rescue therapy may be added to any asthma maintenance regimen and newer combination inhaler therapies may facilitate that choice.

Best Practice Advice 7: After an exacerbation, request a patient follow up visit within a short time to explore steps to prevent future exacerbations; these may include providing self-management education, inhaler technique review, adherence evaluation, smoking cessation advice, and an updated asthma action plan, and updating immunizations

Effective asthma self-management education includes helping patients understand self-monitoring of symptoms and/or lung function (PEF) and their written asthma action plan1. A follow up visit after an exacerbation is essential to review any persistent symptoms, assess current therapy, evaluate and manage modifiable risk factors (such as causative triggers like viral infections—especially those preventable by vaccines [e.g., influenza, respiratory syncytial virus [RSV], SARS-CoV-2]—and allergies, continued smoking or smoke exposure, obesity, poor adherence, and poor inhaler technique), recommend indicated immunizations, and update the asthma action plan1. Immediately after an asthma exacerbation can be an effective time to reinforce these concepts with patients as they may be more motivated to prevent future exacerbations with the current exacerbation fresh in their mind.

Clinicians treating a patient with an asthma exacerbation in an ER should add anti-inflammatory treatment with ICS to inhaled bronchodilators at discharge and recommend an appointment with the patient’s PCC within a short time (3–4 days) while providing a discharge letter including a written asthma action plan.

Principles of self-management of exacerbations via a written asthma action plan include1:

-

How to assess symptoms and detect worsening symptoms that may precede an exacerbation early on

-

How to assess lung function using PEF (if applicable)

-

When and how to increase reliever (ICS plus rapid acting bronchodilator) treatment

-

When and how to increase controller therapy

-

How to review response to treatment and assess next steps

-

When to contact clinician or emergency services

An example asthma action plan can be found on IPCRG’s website at: https://www.ipcrg.org/sites/ipcrg/files/content/attachments/2021-07-14/asthma-action-plan-adult-2021.pdf.

Access to Asthma Care and Treatments

Best Practice Advice 8: Seek to improve timely access to asthma care and treatments to reduce delays in exacerbation prevention and management

Access to adequate asthma care and optimal treatments represents a substantial challenge for many patients across the globe, especially in communities and countries with limited resources, leading to avoidable harm69. The burden of asthma can uniquely affect patients and families across different age, socioeconomic, and racial and ethnic groups. For example, disparate patient groups may face barriers accessing the health care system in certain countries due to language barriers, cultural barriers, geo-political barriers, lack of familiarity with the health care systems and resources, poverty, and low numbers of PCCs and health systems70.

Obtaining the most appropriate asthma medications can be challenging for patients due to cost, cumbersome prescription requirements, and other factors. For example, patients may be prescribed oral corticosteroids to treat an exacerbation since ICS are often more expensive. In other cases, certain treatments are not available due to government, insurer or regulatory restrictions or product supply issues.

Coordinated efforts and advocacy between clinicians, local authorities, and global organizations can complement local resources to improve access to asthma care and treatments for patients with barriers, helping to address inequity. Telemedicine has been increasingly used to care for patients with asthma since the advent of COVID-19, and it can be a valuable adjunct to face-to-face visits, increasing access and increase frequent patient-clinician contact where needed71.

Best Practice Advice 9: Seek to incorporate patients’ and families’ perspectives, preferences, and goals into asthma care

International asthma guidance documents emphasize patient-clinician collaboration for optimal asthma care1,10. As clinicians seek to incorporate patients’ and families’ preferences, goals, and perspectives, patients are more likely to be engaged and understand education in self-management potentially leading to reduced asthma morbidity72,73. Additionally, shared decision-making in asthma management is associated with improved adherence and asthma outcomes74.

Inhalers that combine ICS with bronchodilators that are used as needed can be an effective treatment for some patients with asthma, whereas SABA-only use has been associated with increased exacerbation risk75. In the INSPIRE study, adults with asthma taking an ICS or ICS + bronchodilator maintenance therapy desired treatments that work quickly, most used a SABA daily though they were prescribed maintenance treatment, and many thought they did not need daily medication for asthma when they were feeling well76.

Nonadherence or preference for only treatments that provide immediate relief can limit treatment effectiveness. Nonadherence is often not just refusal to take medication and clinicians can see this as an opportunity for education, or even adaptation to improve adherence. Lack of adherence may be due to time, costs, fears, or cultural issues.

Best Practice Advice 10: Encourage and participate in multidisciplinary team-based care of patients with asthma to ensure continuity of care and improved outcomes

Multidisciplinary care in chronic airway diseases such as asthma can improve outcomes for some patients, especially those with more complex or severe disease77. Key members of the multidisciplinary team may involve the PCC, specialist and consultant clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and mental health professionals, as well as support staff in the clinic that interact with patients77. The entire clinic and each member of the multidisciplinary team should collaborate and have access to the patient’s medical records where possible to ensure continuity of care.

PCCs should consider referring patients with asthma to specialists or consultants when needed, including for the following common reasons8:

-

Suspected alternative pulmonary diagnosis

-

Unable to confirm asthma diagnosis by usual means

-

Suspicion of occupational asthma

-

Persistently uncontrolled disease

-

Severe disease requiring specialized therapy

-

Feeling uncomfortable adequately treating a particular patient

Of note, clinicians should recognize that not all episodes of coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and other airway symptoms indicate an asthma exacerbation1. Furthermore, a diagnosis of asthma should not always be assumed, especially in patients without an initial thorough workup and assessment for asthma. Distinguishing asthma exacerbations from other problems such as laryngeal disorders, vocal cord dysfunction, and dysfunctional breathing can be challenging1. Clinicians should consider whether respiratory symptoms truly indicate worsening of underlying asthma or other symptomatology that does not require treatment intensification.

Conclusion

This international expert consensus identified best practice statements that are intended to facilitate improved prevention and management of asthma exacerbations worldwide. Increased awareness of exacerbation risk, recognizing the risks of SCS and emphasizing the importance of reliever use of ICS as part of exacerbation prevention and management, encouraging patient adherence, and assessing and teaching correct inhaler technique are major themes the expert panel recommends for PCCs to consider implementing.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Change history

09 January 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-024-00411-9

References

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Available from: www.ginasthma.org (2024).

Castillo, J. R., Peters, S. P. & Busse, W. W. Asthma exacerbations: pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunology: Pract. 5, 918–927 (2017).

Skolnik, N. Use of ICS and fast-acting bronchodilators in asthma: past, present, and future. J. Fam. Pract. 72 https://doi.org/10.12788/jfp.0625 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Global trends in the incidence and mortality of asthma from 1990 to 2019: an age-period-cohort analysis using the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Public Health 10, 1036674 (2022).

Most Recent National Asthma Data | CDC. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. January 9, 2023

Mannino, D. M. et al. Surveillance for Asthma—United States, 1980-1999. Morbidity Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51, 1–13 (2002).

Suruki, R. Y., Daugherty, J. B., Boudiaf, N. & Albers, F. C. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm. Med. 17, 74 (2017).

Wu, T. D., Brigham, E. P. & McCormack, M. C. Asthma in the primary care setting. Med. Clin. North Am. 103, 435–452 (2019).

Fletcher, M. J. et al. Improving primary care management of asthma: do we know what really works? NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 29 (2020).

Cloutier, M. M. et al. 2020 focused updates to the asthma management guidelines: a report from the National Asthma Education and prevention program coordinating committee expert panel working group. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 146, 1217–1270 (2020). Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC).

Yang, C. L. et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2021 Guideline update: diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can. J. Respir. Crit. Care Sleep. Med. 5, 348–361 (2021).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Japanese guidelines for adult asthma 2020. Allergol. Int. 69, 519–548 (2020).

Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the primary care management of asthma. Published online September 2019. Accessed January 30. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/asthma/VADoDAsthmaCPGFinal121019.pdf (2024).

National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook. Accessed January 31. https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/ (2024).

EPR⎯3. “Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR⎯2 1997)”. NIH Publication No. 97-4051. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, 2007. Accessed May 12. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/EPR-3_Asthma_Full_Report_2007.pdf (2023).

Greenblatt, M., Galpin, J. S., Hill, C., Feldman, C. & Green, R. J. Comparison of doctor and patient assessments of asthma control. Respir. Med. 104, 356–361 (2010).

Lugogo, N., Skolnik, N., Jiang, Y. A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care. J. Fam. Pract. 71 https://doi.org/10.12788/jfp.0437 (2022).

Murphy, K. R. et al. Development of the Asthma Impairment and Risk Questionnaire (AIRQ): a composite control measure. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 8, 2263–2274.e5 (2020).

Beuther, D. et al. Assessing the Asthma Impairment and Risk Questionnaire’s ability to predict exacerbations. In: Monitoring Airway Disease. European Respiratory Society PA3714 (2021).

Chipps, B. E. et al. Assessing construct validity of the asthma impairment and risk questionnaire using a 3-month exacerbation recall. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. S1081-1206, 00081–00083 (2022).

Yawn, B. Introduction of Asthma APGAR tools improve asthma management in primary care practices. JAA. Published online:1. August (2008).

Yawn, B. P. et al. Use of Asthma APGAR tools in primary care practices: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 16, 100–110 (2018).

Nathan, R. A. et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113, 59–65 (2004).

Schatz, M. et al. The minimally important difference of the Asthma Control Test. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 719–723.e1 (2009).

Juniper, E. F., O’Byrne, P. M., Guyatt, G. H., Ferrie, P. J. & King, D. R. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur. Respir. J. 14, 902–907 (1999).

Azevedo, P. et al. Control of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma Test (CARAT): dissemination and applications in primary care. Prim. Care Respir. J. 22, 112–116 (2013).

Ramsey, R. R. et al. A systematic evaluation of asthma management apps examining behavior change techniques. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 7, 2583–2591 (2019).

Zhang, O., Minku, L. L. & Gonem, S. Detecting asthma exacerbations using daily home monitoring and machine learning. J. Asthma 58, 1518–1527 (2021).

Dabbs, W., Bradley, M. H. & Chamberlin, S. M. Acute asthma exacerbations: management strategies. Am. Fam. Phys. 109, 43–50 (2024).

Plaza Moral, V. et al. GEMA 5.3. Spanish guideline on the management of asthma. Open Respir. Arch. 5, 100277 (2023).

Chan-Yeung, M., Chang, J. H., Manfreda, J., Ferguson, A. & Becker, A. Changes in peak flow, symptom score, and the use of medications during acute exacerbations of asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, 889–893 (1996).

Agusti, A. et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 410–419 (2016).

Aldridge, R. E. et al. Effects of terbutaline and budesonide on sputum cells and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161, 1459–1464 (2000).

Tattersfield, A. E. et al. Exacerbations of asthma: a descriptive study of 425 severe exacerbations. The FACET International Study Group. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 160, 594–599 (1999).

Ghebre, M. A. et al. Severe exacerbations in moderate-to-severe asthmatics are associated with increased pro-inflammatory and type 1 mediators in sputum and serum. BMC Pulm. Med. 19, 144 (2019).

Shrestha Palikhe, N. et al. Th2 cell markers in peripheral blood increase during an acute asthma exacerbation. Allergy 76, 281–290 (2021).

Miller, M. K., Lee, J. H., Miller, D. P. & Wenzel, S. E. TENOR Study Group. Recent asthma exacerbations: a key predictor of future exacerbations. Respir. Med 101, 481–489 (2007).

AsthmaStats: Uncontrolled Asthma among Adults, 2019 | CDC. August 12, 2022. Accessed March 31. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthma_stats/uncontrolled-asthma-adults-2019.htm (2023).

AsthmaStats: Uncontrolled Asthma Among Children With Current Asthma, 2018–2020 | CDC. August 22, 2022. Accessed March 31. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthma_stats/uncontrolled-asthma-children-2018-2020.htm (2023).

Bleecker, E. R., Gandhi, H., Gilbert, I., Murphy, K. R. & Chupp, G. L. Mapping geographic variability of severe uncontrolled asthma in the United States: Management implications. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 128, 78–88 (2022).

Ding, B. & Small, M. Disease burden of mild asthma: findings from a cross-sectional real-world survey. Adv. Ther. 34, 1109–1127 (2017).

Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills; The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). RCP London. August 11, 2015. Accessed April 22. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills (2024).

Engelkes, M., Janssens, H. M., de Jongste, J. C., Sturkenboom, M. C. J. M. & Verhamme, K. M. C. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 45, 396–407 (2015).

Vähätalo, I. et al. 12-year adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in adult-onset asthma. ERJ Open Res. 6, 00324–02019 (2020).

Vähätalo, I. et al. Long-term adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and asthma control in adult-onset asthma. ERJ Open Res. 7, 00715–02020 (2021).

Paracha, R. et al. Asthma medication adherence and exacerbations and lung function in children managed in Leicester primary care. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med 33, 12 (2023).

Papi, A. et al. Albuterol–Budesonide fixed-dose combination rescue inhaler for asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2071–2083 (2022).

Chipps, B. et al. Albuterol-budesonide Fixed-dose Combination (FDC) inhaler as-needed reduces progression from symptomatic deterioration to severe exacerbation in patients with moderate-to-severe asthma: analysis from MANDALA. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 151, AB16 (2023).

Israel, E. et al. Reliever-triggered inhaled glucocorticoid in black and Latinx adults with asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. Published online February 26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2118813 (2022).

Beasley, R. et al. Evaluation of Budesonide-Formoterol for maintenance and reliever therapy among patients with poorly controlled asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e220615 (2022).

Janjua, S. et al. Interventions to improve adherence to pharmacological therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD013381 (2021).

Rootmensen, G. N., Van Keimpema, A. R. J., Jansen, H. M. & De Haan, R. J. Predictors of incorrect inhalation technique in patients with asthma or COPD: a study using a validated videotaped scoring method. J. Aerosol. Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 23, 323–328 (2010).

Denholm, R., van der Werf, E. T. & Hay, A. D. Use of antibiotics and asthma medication for acute lower respiratory tract infections in people with and without asthma: retrospective cohort study. Respir. Res. 21, 4 (2020).

Crompton, G. K. et al. The need to improve inhalation technique in Europe: a report from the aerosol drug management improvement team. Respir. Med. 100, 1479–1494 (2006).

Waljee, A. K. et al. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: population based cohort study. BMJ Published online April 12:j1415. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1415 (2017).

Price, D. B. et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J. Asthma Allergy 11, 193–204 (2018).

Heatley, H. et al. Observational UK cohort study to describe intermittent oral corticosteroid prescribing patterns and their association with adverse outcomes in asthma. Thorax Published online December 27:thorax-2022-219642. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2022-219642 (2022).

Hew, M. et al. Cumulative dispensing of high oral corticosteroid doses for treating asthma in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 213, 316–320 (2020).

Bleecker, E. R. et al. Systemic corticosteroids in asthma: a call to action from World Allergy Organization and Respiratory Effectiveness Group. World Allergy Organ J. 15, 100726 (2022).

O’Byrne, P. M. et al. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. N. Engl. J. Med 378, 1865–1876 (2018).

O’Byrne, P. M. et al. Effect of a single day of increased as-needed budesonide–formoterol use on short-term risk of severe exacerbations in patients with mild asthma: a post-hoc analysis of the SYGMA 1 study. Lancet Respir. Med. 9, 149–158 (2021).

Bateman, E. D. et al. As-Needed Budesonide–Formoterol versus Maintenance Budesonide in Mild Asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1877–1887 (2018).

O’Byrne, P. M. et al. Budesonide/formoterol combination therapy as both maintenance and reliever medication in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171, 129–136 (2005).

Scicchitano, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol single inhaler therapy versus a higher dose of budesonide in moderate to severe asthma. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 20, 1403–1418 (2004).

Rabe, K. F. et al. Budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler for maintenance and relief in mild-to-moderate asthma: a randomized, double-blind trial. Chest 129, 246–256 (2006).

Calhoun, W. J. et al. Comparison of physician-, biomarker-, and symptom-based strategies for adjustment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adults with asthma: the BASALT randomized controlled trial. JAMA 308, 987–997 (2012).

Panettieri, R. A. et al. Non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids: an updated view. Trends Pharm. Sci. 40, 38–49 (2019).

Alangari, A. A. Genomic and non-genomic actions of glucocorticoids in asthma. Ann. Thorac. Med 5, 133–139 (2010).

Dubaybo, B. A. The care of asthma patients in communities with limited resources. Res Rep. Trop. Med 12, 33–38 (2021).

Nanda, A. et al. Ensuring equitable access to guideline-based asthma care across the lifespan: Tips and future directions to the successful implementation of the new NAEPP 2020 guidelines, a Work Group Report of the AAAAI Asthma, Cough, Diagnosis, and Treatment Committee. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 151, 869–880 (2023).

Persaud, Y. K. Using telemedicine to care for the asthma patient. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 22, 43–52 (2022).

Guevara, J. P., Wolf, F. M., Grum, C. M. & Clark, N. M. Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 326, 1308–1309 (2003).

Gibson, P. G. et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD001117. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001117 (2023).

Wilson, S. R. et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181, 566–577 (2010).

Lugogo, N. et al. Real-world patterns and implications of short-acting β2-agonist use in patients with asthma in the United States. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 126, 681–689.e1 (2021).

Partridge, M. R., van der Molen, T., Myrseth, S. E. & Busse, W. W. Attitudes and actions of asthma patients on regular maintenance therapy: the INSPIRE study. BMC Pulm. Med. 6, 13 (2006).

McDonald, V. M., Harrington, J., Clark, V. L. & Gibson, P. G. Multidisciplinary care in chronic airway diseases: the Newcastle model. ERJ Open Res. 8, 00215–02022 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was funded by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP. The funder played no role in conceptualizing, reviewing, or influencing the content or writing of this manuscript. The authors thank IPCRG for assisting in the formation of the expert panel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S., B.Y., J.C.S., M.M., A.B., W.L.W., A.U., T.W., and S.B. participated in conceptualizing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. A.U. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

N.S. reports the following competing interests: Advisory Boards and Consultant - AstraZeneca, Teva, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GSK, Bayer, Genentech, Abbott, Idorsia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Astellas; Speaker - AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, GSK, Teva, Bayer, Heartland, Astellas; Research Support - AstraZeneca, GSK, Novo Nordisk, Novartis. B.P.Y. reports the following competing interests: consultant and member of advisory boards related to asthma for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, TEVA, Novartis, and Moderna. J.C.S. reports the following competing interests: Chair of the Asthma Right Care Strategy Team: International Primary Care Respiratory Group; Receipt of grants/research support: AstraZeneca and GSK; Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees: AstraZeneca, GSK, Bial, Sanofi, Medinfar; Participation in a company sponsored speaker’s bureau: AstraZeneca, Sanofi. M.M. reports the following competing interests: advisory board honoraria, lecture honoraria and travel bursary from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, and Menarini. A.B. reports no relevant competing interests. W.L.W. reports the following competing interests: Consultant and speaker for AstraZeneca. A.U. reports no relevant competing interests. T.W. reports the following competing interests: consultant for unbranded disease awareness, education, advocacy & research for AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, and Sanofi Regeneron. S.B. reports the following competing interests: Speakers Bureau: Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca.

Ethical approval

This declaration is not applicable, as this work did not involve patient-level data.

CME certification

Readers of this article may receive continuing medical education (CME) credit by completing the survey below, depending on their local regulating bodies. Survey link: https://www.pcrg-us.org/survey/post/asthmaconsensus.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skolnik, N., Yawn, B.P., Correia de Sousa, J. et al. Best practice advice for asthma exacerbation prevention and management in primary care: an international expert consensus. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 34, 39 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-024-00399-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-024-00399-2

This article is cited by

-

Asthma Awareness Questionnaire: Development, Psychometric Validation, and Extent

Pulmonary Therapy (2026)

-

A current assessment of family physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward asthma management in primary care in Turkey according to the GINA strategy report

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2025)